THE GERMAN psychoanalyst Max Eitingon wrote in 1925 that his colleagues could no longer honestly argue that “the factor of the patients paying or not paying has any important influence on the course of the analysis.”1 But Eitingon was merely announcing the fulfillment of Freud’s forecast from the 1918 Budapest speech on the conscience of society. In that speech Sigmund Freud had explicitly disavowed his prewar position, “that the value of the treatment is not enhanced in the patient’s eyes if a very low fee is asked,”2 and had repudiated his earlier 1913 image of the psychoanalyst / physician as medical entrepreneur.3 Until the end of his life Freud supported free psychoanalytic clinics, stood up for the flexible fee, and defended the practice of lay analysis, all substantive deviations from a tradition of physicians’ privilege and their patients’ dependence. His consistent loathing of the United States as “the land of the dollar barbarians” echoed his contempt for a medical attitude he believed to be more American than European, more conservative than social democratic.4 This broad revision in his view of doctors’ fees from 1913 to 1918 resulted partly from the grievous material and psychological deprivations the Freud family endured during the war and partly from momentous shifts in the larger political landscape of the early twentieth century.

Freud’s sense of civic responsibility was not new. As a child he had witnessed the 1868 installation of the aggressively liberal Bürgerministerium (bourgeois ministry) that promoted religious tolerance and progressive social legislation involving secular education, interdenominational marriages, a ban on discrimination against Jews, and a compassionate penal system.5 He admired Hannibal and Masséna, a Jewish general in Napoleon’s army, and was fascinated by the deployment of large-scale military strategies. The idea of becoming a politician seems to have occurred to Freud when, as an adolescent, he “developed a wish … to engage in social activities” and decided to study law.6 Law school would train him in the skills of political leadership, and he would grow up to promote the Austrian liberal’s agenda of social reform. But the economic crash of 1873 that shattered Vienna’s private sector banks and industries, and the city’s economic prosperity in general, struck the same year Freud entered the university. The young Freud was deeply affected by “the fate of being in the Opposition and of being put under the ban of the ‘compact majority’” and reacted by developing what he later called, with irony, “a certain degree of independence of judgement.”7

The experience of anti-Semitism first-hand at the university was, in Freud’s life, a powerful motivation to uncover the roots of individual and social aggression. That Freud should focus on the social context of individual behavior was only natural. His model of the civic-minded liberal Jewish family, largely secular, highly accomplished and hard working, was engrained in cosmopolitan Vienna. “Our father was a truly liberal man,” wrote Freud’s sister, Anna Freud Bernays, about their paterfamilias Jacob,

so much so that the democratic ideas absorbed by his children were far removed from the more conventional opinions of our relatives…. About the middle of the last century, the father was all-powerful in a European family and everyone obeyed him unquestioningly. With us, however, a much more modern spirit prevailed. My father, a self-taught scholar, was really brilliant. He would discuss with us children, especially Sigmund, all manner of questions and problems.8

Not surprisingly then, Emma Goldman, the early American feminist and anarchist leader, found much in common with the young neurologist and was enormously impressed when she heard Freud’s 1896 lecture in Vienna. “His simplicity and earnestness and the brilliance of his mind combined to give one the feeling of being led out of a dark cellar into broad daylight. For the first time I grasped the full significance of sex repression and its effect on human thought and action. He helped me to understand myself, my own needs; and I also realized that only people of depraved minds could impugn the motives or find impure so great and fine a personality as Sigmund Freud.”9

Other liberal activists like Sándor Ferenczi (figure 2), Freud’s great Hungarian psychoanalytic partner, agreed. “In our analyses,” he wrote from Budapest to Freud in 1910, “we investigate the real conditions in the various levels of society, cleansed of all hypocrisy and conventionalism, just as they are mirrored in the individual.”10 Sándor Ferenczi was an affable, round-faced intellectual and socialist physician who had passionately defended the rights of women and homosexuals as early as 1906. The charming son of a Hungarian Socialist publisher, Ferenczi pushed the limits of psychoanalytic theory further and faster than anyone else. In 1912 he established the Hungarian Psychoanalytic Society, home to major psychoanalysts including Melanie Klein, Sándor Radó, Franz Alexander, Therese Benedek, and Alice and Michael Bálint. In 1929 he revived the free clinic he had planned in Budapest at the university ten years earlier, during a brief professorship in psychoanalysis promoted by the revolutionary regime.11 Freud’s remarkable relationship with Ferenczi is conveyed in the course of over twelve hundred letters exchanged between 1908 and 1933, the year Ferenczi died of pernicious anemia. The epistolary dialogue between the two men is highly charged with personal feeling, records their far-ranging exchanges of psychoanalytic theory, and often alludes, in a sad sarcastic way, to the larger effects of social injustice on their patients. Ferenczi describes how the analyst must listen to the patients because only they truly understand how psychoanalysis fosters social welfare. When women, men, and children lead lives truer to their individual natures, society can loosen its bonds and allow for a less rigid system of social stratification. His analytical work with a typesetter, a print shop owner, and a countess had shown Ferenczi how each individual experienced society’s repressiveness within their respective social strata, none more than the other but each equally deserving of therapeutic benefits. The high-strung typesetter was terrorized by the demands of the newspaper’s foreman; the owner of a print shop felt crushed by guilt over the swindles he perfected to outwit the corrupt rules of the Association of Print Shop Owners; a young countess’s sexual fantasies about her coachman revealed her sense of inner hollowness. And a servant disclosed the masochistic pleasure she obtained by deciding to accept lower wages from aristocrats instead of higher wages from a bourgeois family. “Next to the ‘Iron Law of Wages,’ the psychological determinants,” Ferenczi summarized, “are sadly neglected in today’s sociology.”

2 Portrait of Sándor Ferenczi painted by Olga Székely-Kovács (Judith Dupont)

What might seem to be Freud’s postwar awakening to the harsher realities of life and to social inequality had actually been stirring for years, often in exchanges between the two same friends. “I have found in myself only one quality of the first rank, a kind of courage which is unshaken by convention,” Freud wrote in 1915 to Ferenczi, and he postulated that their psychoanalytic discoveries stemmed from “relentless realistic criticism.”12 Indeed political reality called for scrutiny on many levels. In 1915 Freud was still loyal to Franz Joseph and to the Vienna where assimilated Jews thrived on high culture, intellectual pursuits, and a politics of social reform. But by then the war had started and the reactionary mayor Karl Lueger, a right-wing populist and anti-Semite, and the Christian Social Party he cofounded in 1885, had superseded the Viennese liberals and dominated municipal politics until World War 1. By 1917 Freud’s family life and professional practice had been thoroughly disrupted. He wrote to Ferenczi of the “bitter cold, worries about provisions, stifled expectations…. Even the tempo in which one lives is hard to bear.”13 Sixty-two years old and frankly impatient with battles and the old idea of the absolutist state, Freud remarked that “the stifling tension, with which everyone is awaiting the imminent disintegration of the State of Austria, is perhaps unfavorable.” But, he continued, “I can’t suppress my satisfaction over this outcome.”14

Even before war’s end Freud’s September 1918 address to the Fifth International Psychoanalytic Congress concentrated specifically on the future, not on the war or individual conflict. The speech appealed for postwar social renewal on a vast scale, a three-way demand for civic society, government responsibility, and social equality. To many of his psychoanalytic colleagues, diplomats and statesmen, friends and family members who listened to Freud read his essay on the future of psychoanalysis, that beautiful autumn day in Budapest augured a bold and new direction in the psychoanalytic movement. Anna Freud and her brother Ernst had accompanied their father to the congress, and the British psychoanalyst Ernest Jones (who could not attend) later claimed that Freud uncharacteristically read his paper15 instead of producing a speech extemporaneously, and upset his family.16 But in the cautiously festive atmosphere that predominated on September 28 and 29, Freud’s speech before this sophisticated audience was far more seditious in meaning than in delivery. He would lead them along an unexplored path, he said, “one that will seem fantastic to many of you, but which I think deserves that we should be prepared for it in our minds.”17 He invoked a series of modernist beliefs in achievable progress, secular society, and the social responsibility of psychoanalysis. And he argued for the central role of government, the need to reduce inequality through universal access to services, the influence of environment on individual behavior, and dissatisfaction with the status quo.

“It is possible to foresee that the conscience of society will awake,” Freud proclaimed,

and remind it that the poor man should have just as much right to assistance for his mind as he now has to the life-saving help offered by surgery; and that the neuroses threaten public health no less than tuberculosis, and can be left as little as the latter to the impotent care of individual members of the community. Then institutions and out-patient clinics will be started, to which analytically-trained physicians will be appointed so that men who would otherwise give way to drink, women who have nearly succumbed under the burden of their privations, children for whom there is no choice but running wild or neurosis, may be made capable, by analysis, of resistance and efficient work. Such treatments will be free.” Freud continued. “It may be a long time before the State comes to see these duties as urgent,” he said, “… Probably these institutions will be started by private charity. Some time or other, however, it must come to this.18

Freud’s argument concerned nothing less than the complex relationship between human beings and the larger governing social and economic forces. Implicitly he was throwing in his lot with the emerging social democratic government.

Even in 1918 psychoanalysis was at imminent risk of premature irrelevance and isolation brought on by elitism. The same fervent independence that had driven the psychoanalytic movement, relatively marginal to Vienna’s medical and academic communities and practiced by an eclectic group of free thinkers, now threatened its durability. Its economic survival depended on a new governmental configuration, one in which the state accepted responsibility for the mental health of its citizens. In a series of ideological positions intended to destigmatize neurosis, Freud was proposing that only the state could place mental health care on a par with physical health care. Individuals inevitably hold a measure of bias toward people with mental illness, and this limits our ability to provide trustworthy care. Redefining neurosis from a personal trouble to a larger social issue places responsibility for the care of mental illness on the entire civic community.19

Freud endorsed the idea that a traditional monarchy’s power to set a country’s laws should now be redistributed democratically to its citizenry. Like his friends and contemporaries the Austrian Socialist politician Otto Bauer and the Social Democrat Victor Adler, Freud believed that social progress could be achieved through a planned partnership of the state and its citizens. Citizens had the right to health and welfare and society should be committed to assist people in need within an urban environment deliberately responsive to the developmental needs of children and worker’s families. In practical terms, he now demanded an interventionist government whose activist influence in the life of the citizens would forestall the increasingly obvious despair of overworked women, unemployed men, and parentless children. The political and social gains derived from the psychoanalysts’ new alliances would, at the very least, confer legitimacy on a form of mental health treatment often practiced by nonphysicians or by physicians reluctant to join the establishment.

Freud concluded his Budapest speech with a demand for free mental health treatment for all. He developed the argument for founding free outpatient clinics in the smoothly systematic manner of a born statesman. The possibility of shifting psychoanalysis from a solely individualizing therapy to a larger, more environmental, approach to social problems hinged on four critical points: access, outreach, privilege, and social inequality. First, the psychoanalyst’s “therapeutic activities are not far-reaching.”20 As if anticipating his critics, Freud noted how this scarcity of resources conferred on treatment the characteristic of a privilege, and this privilege limited the benefits psychoanalysis might achieve if its scope were broadened. Second, “there are only a handful” of clinicians who are qualified to practice analysis. The shortage of both providers and patients suggested that psychoanalysis might fall into the clutch of a dangerous elitism. This predicament must be overcome if analysts were to alert significantly more people to its curative potential. Third, “even by working very hard, each [analyst] can devote himself in a year to only a small number of patients.”21 This quandary is intrinsic to the intensive and time-consuming format of analytic work, but to Freud it also meant that analysts could not assume a position of social responsibility commensurate with their obligation. Individual analytic patients (called analysands in English, then as now) held to the same appointment at a daily hour five days each week until the treatment was completed. Their treatment usually lasted about six months to a year, perhaps less than we imagine today but, as Freud had commented wryly even in 1913, “a longer time than the patient expects.”22

Freud’s fourth point, that the actual “vast amount of neurotic misery” the analyst can eliminate is “almost negligible” at best compared to its reality in the world, reads like a simple disclaimer. But it is in this passage that the social consciousness of Freud’s adolescence and university days reemerges. Human suffering need not be so widespread in society nor so deeply painful individually. Moreover, suffering does not stem from human nature alone, because it is, at least in part, imposed unfairly and largely according to economic status and position in society, a social inequality vividly depicted in Ferenczi’s 1910 letter. Inequality, Freud summarized, is the fundamental problem, and he lamented how explicit socioeconomic factors confine psychoanalytic treatment to the “well-to-do-classes.” Affluent people “who are accustomed to choos[ing] their own physicians” are already able to influence their treatment. But poor people, who have less choice in their medical care, are precisely those who have less access to psychoanalytic treatment and its benefits.23 Psychoanalysis had become socially and economically stratified early in its development. At this crucial juncture in its short history, its lack of social awareness has rendered it virtually powerless. “At present we can do nothing for the wider social strata, those who suffer extremely from neuroses.”24

Who could better reverse this course than this very audience? Freud’s September 28 speech, born more of political anger than wartime dejection, had an astonishing effect on its listeners. The concept of the free mental health clinic may have predated the Budapest congress, but the number of organizational projects launched there by the assembled participants, especially Anton von Freund, Max Eitingon, Ernst Simmel, Eduard Hitschmann, and Sándor Ferenczi, was extraordinary. Eitingon and Simmel would open the Berlin Poliklinik in 1920, Hitschmann would start a free clinic in Vienna in 1922, and Simmel would establish the Schloss Tegel free inpatient clinic. Ferenczi opened the free clinic in Budapest somewhat later, in 1929. Though Ernest Jones could not travel to Budapest to attend the congress because of war restrictions in 1918, he nevertheless started the London Clinic for Psychoanalysis in 1926. Melanie Klein, Hanns Sachs, Sándor Radó, and Karl Abraham were also in that audience and all became key players in the Berlin Poliklinik.

For the moment the grimness of the last few contentious months of 1918 gave way to political idealism, good company, and renewed confidence in Freud and psychoanalysis. “Under a walnut tree in the garden of one of those wonderful restaurants in Budapest … [we] chatted confidentially and privately around a big table,”25 recalled Sándor Radó of their celebratory mood. As conference secretary and coleader of the Budapest society under Ferenczi, the young Radó and his colleague Geza Roheim, the future anthropologist, were pleasantly surprised to dine so informally with Freud and Anna Freud. Their conversations continued on the Danube steamer provided by the city for the analysts’ transportation between their hotel and the meetings at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The visitors were hosted at the splendid new Gellértfürdö Hotel, still famous for its beautifully tiled thermal baths. Budapest’s Mayor Bárczy and other city magistrates publicly welcomed psychoanalysis and graciously accommodated the congress with receptions and private banquets. Except for the avowed Viennese pacifist Siegfried Bernfeld and Freud, most of the analysts present in Budapest had enlisted as army psychiatrists and all attended the conference in uniform. High-level military and medical officials from Hungary, Austria, and Germany officially represented their governments’ delegation to the convention and mingled with the families and guests of the forty-two participating analysts.

Freud’s speech may have been seditious, but it must have been incredibly stimulating as well because so many of the analysts in the audience became powerful proponents of the free clinics. Among them the young Melanie Klein, who saw Freud in person for the first time at this congress, said she was overcome by “the wish to devote [her]self to psychoanalysis.”26 Klein would go on to become the originator of play therapy in child analysis, the framer of an extended dual drive theory, a truly principled follower of Freud. But at the 1918 congress she was still “Frau Dr. Arthur Klein” and mother of three, an analysand of Ferenczi’s and member of the Budapest society since 1914. Anna Freud and Ernst, Freud’s youngest son who had been fighting on the front lines for the last three years, would later become immersed in the free clinics. Anna, Freud’s devoted youngest daughter and the only psychoanalyst of his six children, was a licensed teacher who developed experimental schools with new early childhood educational methodologies for Vienna’s inner-city families. Whether or not in 1918 either Anna or Ernst were ever particularly disturbed by their father’s speech, or merely surprised, both were nevertheless to join his social democratic platform shortly. Progressive politics, like psychoanalysis, struck them as a basic element of life.

The leader they had chosen to merge psychoanalysis and social reform was a wealthy Hungarian owner of breweries and an analytic trainee just appointed general secretary of the International Psychoanalytic Association (IPA). Anton von Freund (Antal Freund von Tószeghi) was a friend and patient of Freud and Ferenczi’s. He was a young idealist with a doctorate in philosophy who believed that both his recent bout with cancer and his depression had been successfully treated with psychoanalysis. Toni, as von Freund was fondly nicknamed, donated two million crowns for the promotion of psychoanalysis by underwriting two significant projects, a publishing house and a major multi-faceted Institute in Budapest that would house a free outpatient clinic. “Materially we shall be strong, we shall be able to maintain and expand our journals and exert an influence,” Freud wrote to Abraham after talking with von Freund about his plans. “And there will be an end to our hitherto prevailing penuriousness,” Freud added.27 The publishing enterprise, the Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag (originally Bibliothek), started up the following year. Its first book-length project collected the 1918 colloquium’s main papers into one volume, called “Psychoanalysis and the War Neuroses,” with an introduction by Freud.28

The institute Toni Freund had forecast would help “the masses by psychoanalysis … which had hitherto only been at the service of the rich, in order to mitigate the neurotic sufferings of the poor.”29 He died before this vision could be realized, but Freud described it later as a project that would combine the teaching and practice of psychoanalysis under one roof, with a research center and an outpatient clinic added. A large group of analysts would be trained at the institute and then remunerated specifically “for the treatment of the poor” at the clinic. Von Freund and his friends anticipated that Ferenczi would be the director and Toni would maintain administrative and financial responsibility. Though a clinic would not actually appear in Budapest until 1929, such a scheme was in keeping with the municipal government’s design for urban inpatient and ambulatory psychoanalytic treatment. The mayor of Budapest, Stefan Bárczy, promised to facilitate the allocation of von Freund’s considerable financial legacy and, as Freud recalled, “preparations for the establishment of Centres of this kind were actually under way, when the revolution broke out and put an end to the war and the influence of the administrative offices which had hitherto to been all-powerful.”30 Indeed the huge political shifts sweeping Hungary, from liberal monarchist to radical left to dictatorial, undermined most of these promises. In seemingly boundless complex transactions over the next few years, the von Freund funds would shift between banks and what had been a considerable sum virtually evaporated. Apparently the public press in Budapest was less accepting of psychoanalysis than the municipal government and, once alerted to von Freund’s bequest, sought out experts to testify against the clinic. “Psa is not a recognised science. No doubt [this testimony] is largely political (anti-semitic and anti-Bolshevik),” Ernest Jones observed to his Dutch colleague, Jan van Emden.31 In other countries though, the free outpatient clinics, both the most crucial and the most polemical aspect of von Freund’s project, were built along the lines laid out at that September 1918 conference.

In the midst of negotiations for the free clinics and, to some, for the future of psychoanalysis itself, Ferenczi, Ernst Simmel, and Karl Abraham made public their recent experiences with “war neurosis,” the controversial psychiatric diagnosis of trauma among soldiers. All three physicians already had significant military and psychoanalytic experience (and all were destined to be a founder of a free clinic) before they came to the Budapest conference. Abraham, a self-confident man in his thirties with blond good looks and an adventurous spirit, recalled his first treatment of war neurosis. “When I founded a unit for neuroses and mental illness in 1916,” Abraham remembered, “I completely disregarded all violent therapies32 as well as hypnosis and other suggestive means…. By means of a kind of simplified psychoanalysis, I managed to … achieve comprehensive relaxation and improvement.”33 As chief psychiatrist of the twentieth army corps in Allenstein, West Prussia, Abraham had set up a ninety-patient observation unit with his Berlin colleague Hans Liebermann. Hungarian army officials were impressed by the results and decided to use psychoanalysis to treat the psychiatric symptoms seen among soldiers traumatized in the course of duty.

Figure 3 belongs somewhere within or after the next paragraph.

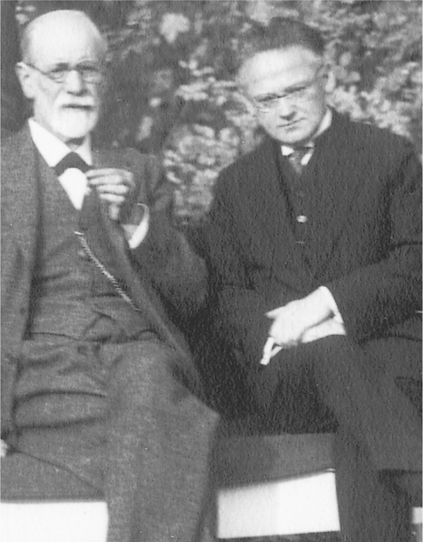

Ernst Simmel (figure 3), then the Prussian Royal Army’s senior physician in charge of a specialized military hospital for war neurotics in Poznan (Posen), was among the first psychoanalysts to appreciate Abraham’s work. Psychoanalysis could be conducted successfully under war conditions, he said, “but only rarely permits a more extensive individual analysis. I endeavoured to shorten the duration of the treatment … to two or three sessions.”34 Simmel drew on his two years of intense field experience as superintendent of military psychiatry to develop the vivid interpretive diagnoses and treatments he described at the conference. In 1918 Freud arranged to have Simmel’s observations published in a short but striking book, the first volume issued by the new Verlag.35 “As a result of this publication,” Freud said later, “th[is] Psycho-Analytical Congress was attended by official delegates of the German, Austrian and Hungarian Army Command, who promised that Centres should be set up for the purely psychological treatment of war neuroses.”36 By now only a few conservative psychiatrists still thought of neurotic soldiers as deviant or disloyal, and complaints of severe anxiety, phobias, and depressions accompanied by trembling, twitching, and cramps were viewed as genuine signs of illness.

3 Freud and Ernst Simmel at Schloss Tegel (Freud Museum, London)

Sándor Ferenczi’s interest in war neurosis had military origins as well. The Hungarian government had acclaimed Ferenczi’s work with psychologically injured soldiers early in the war. Initially a regiment physician on duty in the small Hungarian town of Papa, Ferenczi was transferred to Budapest and made director of the city’s health services for soldiers with psychiatric disorders in 1915. The chief medical officer of the Budapest Military Command commissioned Ferenczi to design an entire hospital-based psychoanalytic ward in Budapest. Residential quarters would be adapted to treat men “brain crippled [by the war with] organic injuries and traumatic neuroses,” modeled at least in part on the therapeutic institute in Vienna of Emil Fröschels, a colleague of the psychoanalyst Alfred Adler.37 Thrilled that psychoanalysis had achieved scientific respectability, Ferenczi shared with Freud his dream of a “preliminary study [for] the planned civilian psychoanalytic institution,” which would start with about thirty patients in 1918.38 Istvan Hollós, a member of the Hungarian society then running the psychiatric hospital in Lipometzo, or Max Eitingon, now applying hypnosis with great success at an army base, or both together, would make excellent assistant directors, Freud suggested. Since 1915 Eitingon had supervised the psychiatric observation divisions of several military hospitals, one in Kassa (Kachau) in northern Hungary and the other in Miskolcz, a small industrial town in eastern Hungary. Together at the Budapest conference for the first time since the beginning of the war, Eitingon along with Ferenczi, Simmel, and Abraham began to set down policies for their civilian practice, derived from experience in military psychiatry. Of utmost concern was the threefold idea of barrier-free, non-punitive, and participatory access to psychoanalytic treatment. Sándor Ferenczi introduced the technical concept of “active therapy” during these discussions of war neurosis and initiated a clinical controversy that has lasted even until today. Throughout the history of psychoanalysis, and indeed much of modern mental health treatment, the debate between proponents of the therapist’s direct verbal support of the patient, on the one hand, and the therapist’s role as an interpretive facilitator of patient’s quest for inner knowledge, on the other hand, has shifted from decade to decade. In all likelihood encouraged by Freud’s interventionist speech on the role of the state, Ferenczi’s own address proposed a psychoanalytic technique featuring time limits, tasks, and prohibitions.

For Freud, war neurosis was a clinical entity largely analogous to “traumatic neuroses which occur in peace-time too after frightening experiences or severe accident” except for “the conflict between the soldier’s old peaceful ego and his new warlike one.”39 He was describing what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD, a cluster of psychiatric symptoms (depression, hypochondria, anxiety, and hallucinatory flashbacks) experienced by men and women exposed to trauma. The diagnosis required drawing a necessary distinction between an involuntary psychological condition and somewhat more deliberate actions like malingering, lying, desertion, and lack of patriotism. For Simmel, who first articulated the concept of war neurosis, the designation had to be applied very carefully. “We gladly abstain from diagnoses out of desperation, “he wrote, but warned that society could not afford to ignore “whatever in a person’s experience is too powerful or horrible for his conscious mind to grasp and work through filters down to the unconscious level of his psyche.”40 The designation of “war neurosis,” which encapsulated all the moral ambiguities of a psychiatric diagnosis, would resurface in 1920 when Freud was called by the Vienna war ministry to testify against the neurologist Julius Wagner-Jauregg.

“Political events absorb so much of one’s interest at present,” Karl Abraham wrote to Freud one month after the Budapest congress, “that one is automatically distracted from scientific work. All the same, some new plans are beginning to mature.”41 The month of November 1918 was as memorable for Austria as for psychoanalysis and indeed for the rest of the Western world. By November 10 Freud cheerfully advised Jones that “our science has survived the difficult times well, and fresh hopes for it have arisen in Budapest.”42 The following day, Armistice Day, Freud shifted from psychoanalysis to larger worldly concerns: the Hapsburgs, he wrote to Ferenczi on November 17 “left behind nothing but a pile of crap.”43 The map of Freud’s political world was changing fast. From Schönbrun Palace to Madrid’s Escorial, from the thirteenth to the twentieth centuries, the Hapsburg Empire’s seven-hundred-year domination of Europe had spanned eleven countries and fourteen languages. Now it was over, leaving in its wake revolutions, newborn nations, and a few ambitious governments trying to relieve human suffering. In Germany, once the kaiser abdicated, the Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed a republic. Austria shrank both in physical size and in political power from the immensity of the Hapsburg Empire to a smaller, economically ravaged, but independent republic. At its height Vienna had been the capital of Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, northern Italy, and parts of Poland. And while the new Austria was not currently faced with the pressure of managing a huge multiprovince administration, the government’s need for effective leadership was urgent. Among these, the physician and Social Democrat Victor Adler had a particularly inventive political outlook that accommodated the atypical field of psychoanalysis. Scorned by Karl Lueger and the Christian Socials, Adler promoted a unique identity for the Viennese Social Democratic Workers’ Party (also known as the Austrian Socialist, SDAP, or as the Austro-Marxist Party) grounded in the combined values of liberal intellectuals and workers’ movements.

Victor Adler was a large affable-looking man with wavy brown hair, steel-rimmed eyeglasses, and a thick moustache. First as an Armenarzt (physician to the poor) and later as a government inspector touring factories in Germany, Switzerland, and England as well as his native Austria, Victor Adler’s critical early observations of ordinary household life led him to join the politics of social reform. In 1886 he founded the first Social Democratic weekly, Gleichheit (Equality), and in 1889 the Arbeiterzeitung (Workers’ Times), a journal that still exists today. His personality appealed even to those who resisted Austria’s shift to a self-governing constitutional republic. Adler belonged to the Pernerstorfer Circle, a Viennese group that rejected nineteenth-century Austrian liberalism in favor of expanded suffrage, socialist economic structures, and cultural renewal based in art, politics, and ideas. Thus, he was at once a nationalist and a socially committed medical doctor whose personal attempts to meet the health concerns of poor people fueled a political vision of social reform.44 Adler died suddenly the day the war ended, November 11. His friend Sigmund Freud, who yearned neither for the former monarchy nor traditional structure, wrote to Ferenczi that day. “We lost the best man, perhaps the only one who might have been up to the task,” he said. “Nothing can likely be done with the Christian Socialists and the German Nationalists.”45 Viennese Jews had necessarily supported Franz Joseph because he offered protection against anti-Semitism.46 Now the pro-Hapsburg Christian Socials were openly, and dangerously, opposed to Vienna’s Jews. Freud and Adler had surely discussed these concerns along with their views on Viennese politics and culture and thought back on high school adventures with their fellow activist, Heinrich Braun.

An early figure in Freud’s lifelong series of intense relationships with influential men, Braun seems to have inspired his friend’s desire for a reformist’s career when they met as adolescents at the Gymnasium in the early 1870s. Braun was “my most intimate companion in our schooldays,” Freud recalled years later.47 “Under the powerful influence of a school friendship with a boy rather my senior who grew up to be a well-known politician I developed a wish to study law like him.”48 Eventually Freud chose to study natural sciences and then medicine, but his adolescent convictions about social justice and the need for political leadership endured all his life. Like Victor Adler, Heinrich Braun became a prominent socialist politician and an expert on the theory of social economy. When Braun died in 1926, Freud sent a condolence note to his classmate’s widow and made clear how deeply politics ran in the thoughts shared by all three friends. “At the Gymnasium we were inseparable friends…. He awakened a multitude of revolutionary trends in me…. Neither the goals nor the means for our ambitions were very clear to us…. But one thing was certain: that I would work with him and that I could never desert his party.”49 He never did. He shared with Braun, Adler, and yet another childhood friend, Eduard Silberstein, the background of the nineteenth-century tradition of liberal, scholarly, atheist doctors. As early as 1875 Freud asked Silberstein if the Austrian Social Democrats “are also revolutionary in philosophical and religious matters; I am of the opinion that one can more easily learn from this relationship than from any other whether or not the basic trait of their character is really radical.”50 The adolescent Freud wondered whether radicalism, philosophical or religious, in someone like himself was more central to a revolutionary position than even the progressivism of social democracy. This was to be Freud’s journey: to craft a revolutionary position, to blend increasingly adventurous liberalism with science, to bend the depth and traditional graciousness of the humanities to serve the needs of the people. In the end the adolescent struggle was resolved through the discovery of psychoanalysis. Much later the adult Freud rented the apartment that had previously belonged to Victor Adler’s family at 19 Berggasse, on a street of solid Viennese buildings down a steeply inclined hill near the University of Vienna. Victor Adler died the day before the Austrian republic was decreed, but his ideas had planted the seeds of the era known as Rotes Wien, or Red Vienna. Like the Weimar Republic, Austria’s progressive First Republic would last less than twenty years.

In Red Vienna the birth of a social democratic state turned, even more than on Braun or Adler, on the influence of Dr. Julius Tandler, the University of Vienna anatomist whose role as administrator of the new republic’s pathbreaking welfare system was hardly outweighed by his brilliant academic reputation. Now in his early fifties, Tandler had been a professor at the University of Vienna since 1910 and dean of the medical faculty during the war. He took over as undersecretary of state for public health on May 9, 1919. Over the next ten years Tandler fought for a vast extension of public health and welfare services and implemented a comprehensive political solution to the city’s high rates of infant mortality, childhood illness, and, ultimately, family poverty. The Social Democrats “hoped to take away the shame of being born an illegitimate child,” remembered the psychoanalyst Else Pappenheim. “Any baby born out of wedlock,” she said, “was adopted by the city. It stayed with the mother who, if she was poor, was sent for six weeks to a home with the baby—but it was officially adopted.”51 Even a group of American physicians visiting Vienna were impressed. “Nowhere else have the theory and practice of legal guardianship for illegitimate and dependent children been pushed so far,” they observed.52 Actually pediatric medical care originated in Austria and the principle of guardianship, the state in essence substituting for paternal support of illegitimate children, had long been in effect. Within a few years of the war the extraordinary success of child services would dull most criticism. For Julius Tandler healthy children were simply the necessary foundation of a healthy state. Whether in the Vienna City Council or at the university, where his medical students included future prominent psychoanalysts like Erik Erikson, Wilhelm Reich, Otto Fenichel, and Grete and Eduard Bibring, Tandler’s beliefs were as legendary as his irascible temper, his large white moustache, wide-brimmed hat, and bow tie.

Meanwhile Otto Bauer, the mathematician who had assumed the Social Democrats’ chairmanship at Victor Adler’s death, applied the party’s platform of cautious progressivism to Vienna’s economic recovery. Bauer’s new government, which included the attorney and tax expert Robert Danneberg and Hugo Breitner, former director of the Austrian Ländesbank, sought to socialize housing without attacking private property, to build a viable government system based on parliamentary democracy, and to consolidate the country politically and economically. To articulate the complex partnership between urban architecture and social planning, Bauer hired Benedikt Kautsky, son of the theoretician of international socialism Karl Kautsky and editor of his father’s correspondence with Engels and Victor Adler, as his private secretary. Robert Danneberg addressed questions of law and authored a range of new municipal ordinances. Finally, Hugo Breitner became councillor of finance responsible for fiscal and budgetary policy. Together they abolished the prewar taxation system and crafted an “inflation-proof” strategy to protect the city’s revenue in an exceptionally volatile economic environment. They drew up a series of clever redistributive taxation measures that succeeded in balancing the municipal account books while allowing the government to continue functioning within the preexisting capitalist economy. Ten years later, in 1929, outsiders like the American representatives from the Commonwealth Fund who were completing their philanthropic mission in public health found that the strategy had been an impressive achievement on all economic fronts. “The Social Democratic city has run the gamut of experiments in taxation and has pioneered in municipal enterprises—housing for instance—in a fashion that arrests the attention of all Europe,” William French and Geddes Smith reported.53

Between 1918, when World War I ended, and the mid-1930s when fascist incursions began in the streets of Vienna, the début de siècle was a gradual and at times painful breakaway from the alienating rule of monarchy. The October dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy had brought about the abrupt decline of a supranational empire of fifty-two million to a federal state of a mere six million, one-third of whom lived within the boundaries of Vienna. Concurrently the ascent of Deutschösterreich, the self-named rural Austria, led to conflicts with urban Vienna (both the greater area and the former imperial city) that would only end in 1933. Generally conservative and Catholic, agricultural landowners and laborers balked at the idea of sharing food, coal, and raw materials with the city, which to them represented decadence, taxes, and Jews. Red Vienna’s brand of Austro-Marxism, with its belief in social democratic incrementalism in social and political change, sounded the alarm in traditionalist circles. But the support it received from the progressive avant-garde went far toward ensuring its survival. Once the term Austro-Marxism became synonymous with a unique alliance between the liberal arts and the health professions, it shed many of the negative images traditionally applied to movements of the left. Future humanitarian socioeconomic policy could be attained, the Social Democrats believed, through nonviolence and genuinely democratic elections. For the present however, construction of housing, symphony concerts for workers, school reform, ski trips, summer camps for urban children, and cash allotments made clear the party’s commitment to improving the daily reality of human life. A genuine welfare system coexisted with public lectures, libraries, theaters, museums and galleries, sports arenas and mass festivals. The experiment’s success turned on the confluence of several ideological streams that integrated a present-focused materialist, economic view with a reliance on traditional, liberal culture.

Vienna of the years between 1918 and 1934 reached an extraordinarily high level of intellectual production. Linked to Austria by their recent induction into war service, yet alienated from their nation by culture and religion, the modernist composer Arnold Schoenberg and his two celebrated pupils Anton von Webern and Alban Berg formulated the so-called Second, or Twentieth-Century, Viennese School of Music. These controversial composers broke with traditional forms of music and articulated the new twelve-tone system of serial composition. In February 1919 Schoenberg founded a forum for modern music, the Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen (Society for Private Music Performances), where composers presented chamber music, songs, and even operas that dismantled Vienna’s musical heritage and featured the contemporary atonal medium. The Verein ran until 1921, with both Schoenberg’s composition classes and some seats to the performances offered on a pay-as-you can basis. Modern music attracted a small audience. But the young Wilhelm Reich, still in medical school and befriended by Otto Fenichel, Grete Lehner Bibring, and other future psychoanalysts, most of whom played the piano, joined the Schoenberg Verein. In philosophy the Vienna Circle (including Rudolf Carnap, champion of logical positivism) gathered weekly at the University of Vienna between 1925 and 1936 to examine the relationship between mathematical and psychological worlds. And in medicine Guido Holzknecht, already a member of the Vienna psychoanalytic society, pioneered the use of radiology while Clemens Pirquet founded the theory of allergy. Still conscious of their past, institutions like the Bildungszentrale (the social democratic center for adult education) and municipal civic museums sponsored exhibits of Otto Neurath’s pictorial statistics comparing everyday life after the war to the Vienna of long ago. The bridge between art and sociology was built on observations about families. Of all the cultural productions that linked psychoanalysis and Red Vienna, the new architecture for public housing was to demonstrate that communities constructed specifically to meet the needs of urban children and families met essential psychological needs as well.

“The living conditions in postwar Vienna were miserable,” the psychoanalyst Richard Sterba remembered. “The official food rations were so small that one had to supplement them on the black market in order to survive…. At home and at the university there was no fuel for heating and the apartments and classrooms were bitter cold…. We [all] developed frostbite.”54 With the number of marriages and new families surging at war’s end, Vienna’s housing shortage became particularly acute for young people like Sterba. Returning former imperial civil servants and military personnel, newlyweds and even small families found themselves subletting rooms or renting “sleeping spaces” in existing apartments. The demand for housing grew stronger as workers were evicted from their sublets and left without alternative housing arrangements. Those tenement buildings where indigent families remained had neither gas nor electricity, and most residents shared water and toilets in the hallway. Inflation, unemployment, paucity of private capital invested in real estate, and drops in real wages added up to a major housing crisis. Rents had already been capped by the Mieterschutz (tenant protection, also known as rent control), a government decree of January 26, 1917, designed to shield soldiers and their dependent families from rent increases and evictions.

At its core Red Vienna, where Freud lived and worked, was “not so much a theory as a way of life … pervaded by a sense of hope that has no parallel in the twentieth century,” recalled Marie Jahoda, one of the most influential modern social psychologists.55 At the University of Vienna’s Psychological Institute, Karl Bühler, Charlotte Bühler, Paul Lazarsfeld, and Alfred Adler, combined the new “experimental method” with academic psychology and laboratory-based direct observation of infants. At the university’s medical school Wilhelm Reich, Helene Deutsch, and Rudolf Ekstein had started to come together as a second generation of psychoanalysts with a specific, left-wing activist orientation. Reflecting on what Red Vienna meant to this incredible range of social psychologists, developmental psychologists, educators and psychoanalysts, architects and musicians whose calling emerged from an exceptional nexus of ideology and practice, Jahoda remained enthralled by its activist world view. Revolutionism was yet another designation for the spirit of Red Vienna. Helene Deutsch coined this term in her memoirs of her youth as an ambitious Polish-born medical student, as interested in political activism as in psychiatry and later psychoanalysis. As a young woman Helene Deutsch, whose striking classical features were set off by dark upswept hair, was the secret lover of the socialist leader Herman Lieberman and had, in his company, met the influential Marxist Rosa Luxemburg56. Deutsch was one of the few first women admitted to the University of Vienna’s medical school, where she studied anatomy with Julius Tandler just before the war. She was also the only female war psychiatrist allowed to work in Wagner-Jauregg’s clinic. As a physician she particularly admired the Kollwitz team, the socialist artist Käthe and her pediatrician husband (Berlin activists who later formed the Association for Socialist Physicians along with Albert Einstein and the psychoanalyst Ernst Simmel).

Wilhelm Reich was in Vienna too, a passionate young medical intern who stood out even among the two thousand other students. Like most psychoanalysts who lacked a political voice at the start of the war, Reich was radicalized by 1918. Reich, who would join the Ambulatorium as assistant director four years later in 1922, had just come out of military service and enrolled as a medical student. His own memoirs of Red Vienna speak of “everything in confusion: socialism, the Viennese intellectual bourgeoisie, psychoanalysis” to describe this era when all previous assumptions about the interests of government, individuals and society, were all called into question.57 Soon after his first encounter with Otto Fenichel at the medical school, Reich read Fenichel’s “Esoterik” and was enormously impressed because the essay’s images truly captured the turbulence of Red Vienna.58 As he recalled, the paper brought forward, for the first time, a written account of a woman’s political and moral struggle over the right to use her body for reproduction, for sale, or for eroticism whether aimed at herself or others. Reich was challenged by just these same questions, and in fact his later network of free clinics offered free and confidential reproductive care for women. Meanwhile his friends Fenichel, Siegfried Bernfeld, and Bruno Bettelheim were involved with Vienna’s complex Wandervogel groups and, like other young men returning from the front, applauded the movement’s crucial transformation from its prewar pan-German nationalism to an “anti-war, pacifist and leftist” stance.59 Actually, the young reformers represented only one aspect of the youth movement since it had recently split along ideological lines. Left-wing members affiliated with Socialism, Communism, and Zionism while others joined the Christian Nationalists and even more radical right-wing groups, precursors to Nazi organizations such as the Hitler Youth. Bettelheim’s own left-leaning friends were specifically interested in radical educational reform. Inspired by the anarchist Gustav Landauer’s ideal of spontaneous community then in vogue,60 they met on Sundays in the Vienna woods. This was a vast and lush suburban park of inviting beer gardens and elaborate hiking trails, generally a playground where roaming groups of youths gathered for games, songs, and political discussions. Years later Bettelheim still enjoyed telling the story about the day Fenichel interrupted his group, wearing his military uniform. Fenichel was often inconsiderate, but this time he broke into their conversation and started to expound on the views of Sigmund Freud. Freud had just delivered a few of his famous university lectures and the dazzled Fenichel could hardly contain his exuberant fascination with dreams, dream interpretation, and sexuality. Bettelheim, for his part, was in less of a hurry but still curious. “While we had heard vaguely about these theories in our circle, which was eagerly taking up all new and radical ideas,” Bettelheim recalled of his first introduction to psychoanalysis, “we knew nothing of substance about them.”61 Nevertheless, since the fascination seemed to infect Bettelheim’s girlfriend as well, he dashed off to find the real Sigmund Freud. Before long Bettelheim had found his vocation—and recaptured his romantic relationship as well.

“It is good that the old should die, but the new is not yet here,” Freud wrote to his great friend and colleague Max Eitingon in Berlin, just a few weeks just before the end of World War I. Freud’s first glimpse of freedom from war was “frighteningly thrilling.”62 Even in October 1918 Freud had a real sense that remarkable changes at all levels of society were about to transform the world they had known. One month earlier, together with Eitingon and other members of the new IPA who had gathered in Budapest for their fifth international congress, Freud had plotted what he would meaningfully call “Lines of Advance” in the battle for psychoanalysis. They had approved far-reaching plans that would require local psychoanalytic societies to promote clinical research, standardized training programs, and free outpatient clinics. Their mood was confident and eager. The psychoanalyst Rudolf Ekstein remembered how “Anna Freud [and] August Aichorn were concerned not only with theoretical issues but also with practical issues of education. “In Red Vienna of course,” he said, “there was Sigmund Freud.”63