“The position of the polyclinic itself as the headquarters of the psychoanalytic movement”

ON FEBRUARY 24, 1920, Freud dispatched his daughter Mathilde and her husband Robert Hollitscher, the Viennese businessman, to attend the opening ceremonies for the new Berlin Poliklinik für Psychoanalytische Behandlung Nervöser Krankheiten, the first psychoanalytic outpatient center specifically designated as a free clinic. The clinic’s opening was “the most gratifying thing at this time” Freud wrote to Ferenczi, and Mathilde’s presence alongside other prominent members of the psychoanalytic community added a measure of authority to the festivities.1 The Poliklinik, as it came to be known, was the brainchild of Max Eitingon and Ernst Simmel. Their Hungarian friend and benefactor Anton von Freund had died just a month earlier on January 20, leaving the IPA some money but a much larger legacy of unfinished good works and his project for a free clinic in Budapest postponed. “In Berlin there is much better news [than] in Budapest,” Ernest Jones commented to his Dutch colleague Jan van Emden. “They have money for the Policlinic.”2 And indeed Max Eitingon, moneyed and generous, took over where von Freund left off and financed the new clinic’s start-up, now relocated to Berlin, from his private fortune. Eitingon would continue to underwrite the expenses of housing the ever growing Berlin Poliklinik, first at 29 Potsdamerstrasse until 1928 and then on Wichtmanstrasse until its involuntary end in 1933.

Part classical music, part poetry reading, and part ode to psychoanalytic inquiry, the Poliklinik’s February 14 inaugural ceremony proved to be a splendid event. The daylong Programme of festivities showcased performances by members and friends of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Society, and included a Beethoven piano sonata, some Chopin, piano and voice pieces by Schubert and Schoenberg, and art songs by Hugo Wolf. Ernst Simmel read “Presentiment” and “Madness” from Rilke’s Book of Hours. Abraham ended the day with paper on “The Rise of the Poliklinik from the Unconscious.” The program’s overall symbolist themes of human emotion, reality, and nature were reflected in the combination of traditional pieces from the mainstream of German culture with contemporary work suggesting modernity and subjectivity. For music Schubert and Chopin were mixed with Schoenberg, Vienna’s avant-garde composer, identified musically with the Expressionists and politically with the Social Democrats. In poetry the psychoanalysts offset Rilke’s romantic voice with the biting surrealism of Christian Morgenstern’s satire. Rilke was still living in Europe then, enormously popular though still edgy, and, like Freud, an intimate of the Russian intellectual Lou Andreas-Salomé. By the time the day was over, the analysts could revel in a stylish celebration utterly consonant with the cultural overtones of Weimar.

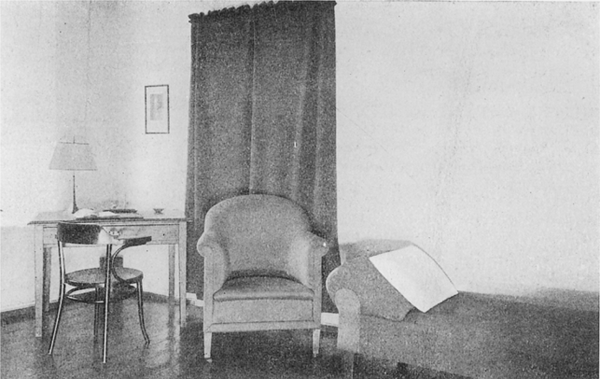

In keeping with his modernist aspirations for the Poliklinik, Eitingon invited Freud’s son Ernst Ludwig (figure 7), the architect and engineer who had trained in Vienna under Adolf Loos, to plan the clinic’s physical layout and furnishings. Within a month Ernst had “won lasting recognition for himself in his designing of the polyclinic, which is admired by everyone,” Abraham wrote to Freud in March.3 Ernst had just arrived in Berlin at the invitation of his close friend Richard Neutra, his classmate in Loos’s Vienna Bauschule architecture studio in 1912 and 1913.4 From 1919 until his forced emigration to London in 1933, Ernst’s years as a Berlin architect were filled with experimentation along the lines of the New Objectivity and the International Style of the 1920s. The commission to design the Poliklinik’s interior space and to refurbish its musty quarters held particular appeal. “I love the conditions stipulated by an existing building of character, “Ernst said years later, “and very often old [ones] have great possibilities in their rooms.”5 This particular suite of rooms at 29 Potsdamerstrasse had been selected and rented as the clinic’s site because of its ideal central location and easy proximity to the Berlin analysts’ own private offices. On the fourth floor of a fairly modest residential building midway up a tree-lined street, the apartment’s five interconnecting rooms were rearranged for treatment or consultation. Light-colored wood double doors soundproofed the consulting or therapy. An unadorned cane couch, a chair and a table, some lamps, and simple portraits on the wall furnished the rooms. Ernst modified his father’s luxuriantly adorned analytic couch, stripped it of ornamentation, and streamlined its shape to produce the model most frequently used today.

7 Ernst Freud, the young architect, in 1926 (Freud Museum, London)

“The fascination of this task is to provide flats of convenience with the minimum of alteration,” Ernst explained in another context, a task made visible in his coherent restructuring of the Poliklinik’s space.6 For Ernst, as for his friend Richard Neutra, modernism meant proportion, regard for the demands of the existing environment, and the use of natural light to integrate the interior and the exterior of the home. Like Neutra, Ernst Freud’s architecture was permeated with ecological and environmental sensitivity. Throughout his career in Austria, Germany, and especially England after 1933, Ernst would design furniture for individual clients and revel in simple functional lines, light woods, and natural fabrics. His architectural projects ranged from factories to private houses but his particular talent was remodeling or “remoulding” houses and adapting them for modern living. Ernst remodeled furniture too. In 1938, when the celebrated ceramist Lucie Rie escaped the Nazis but retained her furniture designed by another modernist architect, Ernst Plischke, Ernst adapted it to her new home in London. His sophisticated built-in bookcases and cupboards, small walnut tables and armchairs made for sparse harmonious living. Ernst Freud’s sense of the organic environment, a style he shared with Neutra, was already discernible in his 1920 designs for the Poliklinik. Dark heavy drapes shaded the consulting offices, while the windows of the larger meeting room, called the Lecture Hall, let in light through muslin curtains. The largest room was also used for conferences, lectures, and meetings. With a sizable blackboard mounted on the front wall and a speaker’s podium, this room held approximately forty Thonet chairs. Ernst’s use of commercially available furniture like these bentwood chairs reflected Loos’s view that the architect’s design should not influence the user’s choice of everyday products.

Similarly simple, well-crafted furniture filled the clinic’s small waiting room, consciously planned to promote a sense of community. Ernst had learned from his architect colleagues at the Bauhaus and in Red Vienna’s Gemeindebauten to design public spaces with an eye to their therapeutic effect. Imbued with Alfred Loos’s beliefs in unadorned forms and, wherever possible, built-in furniture, Ernst fitted the research library into one of the public meeting areas. In fact, Eitingon, foremost a Jewish intellectual who adhered to the curative powers of knowledge, specifically requested that Ernst arrange one room of the clinic as a reading room where all the psychoanalytic literature would be gathered and made available to client and clinician alike.7 The Poliklinik’s deliberately crowded milieu stood in stark contrast to the traditional medical office model with its separate doors and narrow access to the quasi-private practitioner. Clinic patients saw each other regularly and, confidentiality aside, could feel reassured knowing that a group of their peers had been admitted and were waiting for an analytic hour to open. Eitingon believed that this community atmosphere subtly motivated the patients toward self-sufficiency, in what would later be called forms of “milieu therapy.” Once inside the analyst’s room, however, privacy prevailed. Ernst effectively insulated the offices against sound with a series of new techniques (distinctive in his later architectural practice) including double-glazed windows and laminated doors with a plywood core for soundproofing. Altogether these measures were intended to dispel the more frightening aspects of beginning treatment. The prospective patient’s first encounter with the Poliklinik was as scrupulously designed as the clinic’s furniture and statistics.

The Poliklinik issued a formal announcement of its opening:

The Berlin Psychoanalytical Association

opened on 16th February 1920

a

Poliklinik for the psychoanalytical treatment of nervous diseases

at W. Potsdamer Str[asse] 29, under the medical supervision

of Dr. Abraham, Dr. Eitingon, Dr. Simmel

Consultations on weekdays 9–11:30, except Wednesdays.8

From its opening day the Poliklinik’s unexpectedly large influx of adult and child patients was coordinated by Eitingon and Simmel. Their small staff of clinicians, all members of the Berlin society who had agreed to conduct free analyses, was barraged by requests from people with longstanding or chronic problems—both psychological and physiological—and by patients who had gone from one doctor or clinic to another. At least two and a half hours daily (except Wednesdays and Sundays) were allocated to these initial consultations, or intakes, which at first were conducted by the codirectors in tandem. The new patients “suffered especially strongly under their neuroses because of economic need,” Simmel wrote, “or were especially given to material misery precisely as a result of their neurotic inhibition.”9 In the Poliklinik’s first year 350 patients applied for free psychoanalytic treatment. Many of them walked in from the street, enticed by the name on the front door’s classical brass plaque. But more and more were recommended by former patients, friends, or their personal physicians. Some patients read about the official opening of the clinic in local newspapers. The Berlin press had been fairly neutral, not nearly as flattering as the Vienna newspaper coverage of the Ambulatorium would be in 1922, but definitely more favorable than the Budapest clinic would see later in the decade. Berlin’s Die Neue Rundschau, the Fischer Verlag’s prestigious monthly magazine, published Karl Abraham’s long article outlining the principles of psychoanalysis.10 For the moment the city’s academic and psychiatric communities were excited by the Poliklinik and willing to refer patients. While a psychoanalytic service was new to psychiatrists at the Charité, Berlin University’s huge and magnificent teaching hospital, the idea of using a Poliklinik as an alternative to inpatient medical treatment went back at least a hundred years. The practice had started at the Charité in the late nineteenth century and had since become standard throughout Germany’s medical system. In new fields like orthopedics or psychoanalysis intermediate-care polyclinics helped hospitals provide both academic training and general public health. Even before its formal opening the psychoanalytic polyclinic seemed so promising that medical faculty at the Charité considered nominating Abraham for a professorship in psychoanalysis. The position never did materialize but Abraham nevertheless informed Freud that “the polyclinic, which will definitely be opened in January, is arousing great interest on the part of the Ministry [of Education]” and that his collegial relations with the public health officials were bearing fruit.11 The enthusiastic Konrad Haenisch, then heading Berlin’s education ministry, had asked Abraham to draw up an account of their “first experiences at the polyclinic concerning the number of patients attending for treatment” and the size of the audience frequenting society lectures.12 “The Clinic is well attended,” Abraham said cheerily within a month of its opening. At least twenty analyses had been started and the flood of patients (of all ages, occupations, and social standing) continued to be so great that the Poliklinik never advertised again. “For the more distant future there is a project to start a special department for the treatment of neurotic children,” Abraham added. “I should like to train a woman doctor particularly for this.”13 In June, barely three months after this note was sent to Freud, Hermine von Hug-Hellmuth launched the Berlin Poliklinik’s child treatment program.

Hermine von Hug-Hellmuth was “a small woman with black hair, always neatly, one might say ascetically, dressed,” recalled her companion from the Vienna society’s roundtable meetings, Helene Deutsch.14 Even before Melanie Klein and Anna Freud, Hug-Hellmuth had developed child therapies based on games and drawings and, as such, is know as the first practitioner of child analysis. Her views found their way into education, parenting, and child welfare facilities and her practice of treating children in their own homes was picked up by the emerging social work profession. Her beliefs in the impact of family and the larger environment on human development were consistent with Tandler’s social welfare approach to children’s mental health, and she managed the infusion of Freudian psychoanalysis into the city’s growing network of family social services and schools. Fortunately Abraham had foreseen the need for a child analysis treatment and training section and invited Hug-Hellmuth to set it up. Yet her arrival in Berlin may not have been problem free. Although the diplomatic Eitingon (who spoke for the entire staff in his reports and letters to his colleagues) never stated so overtly, the controversy over Hug-Hellmuth‘s short and scabrous book, A Young Girl’s Diary, surely loomed large. Published just the year before in 1919 as an authentic narrative of pubescent female sexuality, and perfectly synchronized with Freudian theory, the Diary proved to be largely fictional. The little book provoked such furor among the analysts that, as Deutsch recalled, one of them “played detective and inquired in all the hospitals whether a man of a certain description had been admitted on the date when the diarist of the Tagebuch reports that her father fell ill.”15 The search proved futile and only further popularized the book. In 1923, the year she returned to Vienna, Hug-Hellmuth finally claimed the work as her personal editing of a genuine adolescent diary (perhaps her own). The adolescent’s story, deceitful or not, contributed to the increasingly accepted twofold idea that adolescents and even younger children suffer from neurotic misery and that such afflictions can be treated with psychoanalysis as successfully as with adults.

We “cannot say that the factor of the patients paying or not paying has any important influence on the course of the analysis.”16 Arguably one of Max Eitingon’s most paradoxical statements, the hypothesis that the fee itself has little or no significant effect on the course of psychoanalytic treatment was as insightful as it was controversial. He used quantitative data to confirm the feasibility of Freud’s belief in public access to psychoanalysis, data that today disprove the conclusions of several class-based analyses of Freud’s case studies.17 He believed that fees for treatment should be discussed, despite some inevitable tension, between the patient and the administrator or clinician. Eitingon could personally handle an individual’s pecuniary and clinical questions at once, but the larger social welfare concerns eventually raised by the issue of free treatment were strikingly complex. The Poliklinik functioned as a private charitable organization, generally independent of state supervision and of the regulatory oversight of Karl Moeli, director of the section for psychiatric affairs created within the medical division of Berlin’s Ministry of Culture. Nevertheless the unusual fee scale generated disagreement both within the clinic and outside it and presumably created some anxiety for certain psychoanalysts accustomed to the private practice model. Melanie Klein, for one, was keenly aware of this. In her little personal diaries from the 1920s, Klein meticulously tabulated the clinical time she owed the Poliklinik down to the minute. Still, Eitingon was confident that being “entirely disinterested materially” in the patient would eventually strengthen the position and authority of the Poliklinik analyst. He confronted doubting analysts who feared—or said they feared, and one wonders about self-interest here—that forsaking the fee meant relinquishing opportunities to pressure a patient into tackling “complexes of vital importance.” His threefold argument suggested that the strength of the “free treatment” rationale is implicit. First, Freud’s Budapest speech specified that “these treatments shall be free,” second, the Poliklinik had no formal guidelines for free treatment, and, third, the analysts’ independence from the issue of fees would have favorable effects on their clinical work.

Free analyses were conducted side by side, at the same time and in the same location, as fee-paying analyses (figure 8). And the same, psychoanalysts treated all cases equally, regardless of the patient’s ability to pay: fee-paying patients were not reserved for the senior analysts, nor was free treatment an obligation for the candidates alone. In effect, a sort of sliding scale of fees from zero upward eliminated the boundary between “free” and “paid” treatment. Senior analysts had little choice. Even Eitingon treated several patients gratis, though he was not known for his clinical acumen. Many of his colleagues, from Sándor Radó to Alix Strachey, agreed that Eitingon had excellent philosophical training and vast cultural sophistication but was too personally inhibited to command a successful clinical practice.18 Nevertheless, the first three full-time salaried employees were Eitingon and Simmel as codirectors, with Anna Smeliansky as their assistant, each working up to fourteen hours every day. New staff members would be added as long as they met three distinct criteria that Abraham outlined to Freud. “Our conditions for working at the Clinic are,” he wrote, “first, sufficient neurological and psychiatric training; second, sufficient knowledge of psycho-analytic literature; third, personal analysis of the candidate.”19 Hanns Sachs would arrive shortly in Berlin to conduct many of these didactic analyses. Volunteer society members covered for each other’s illnesses and vacations, and they would “oversee the Poliklinik as Eitingon’s representative during his trips,” as Abraham was quick to reassure his international colleagues.20

8 Treatment Room no. 2 at the Berlin Poliklinik (Library of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute)

“The position of the polyclinic itself as the headquarters of the psychoanalytic movement,” Freud decided to write to Abraham, “would only be strengthened” by Theodor Reik’s prospective move to Berlin.21 Reik was a chronically impoverished literary man and the original model of the nonphysician analyst. His practice eventually created such furor that Freud was prompted to publish The Question of Lay Analysis. If Reik moved to Berlin, Freud thought, he could relieve Sachs of the burden of conducting all the candidates’ training analyses, provide Abraham with a trusted replacement for the lecture series, and build up the stature of Poliklinik within the IPA and wider academic circles. Meanwhile his absence from Vienna would smooth out some of the home society’s internal squabbling. But neither Abraham nor Eitingon welcomed Freud’s idea of moving Reik to Berlin. They were quite happy with Sachs’s abilities and, perhaps more important, unsure of Reik’s political commitment. Besides the inspiring young analyst Otto Fenichel had just moved to Berlin from Vienna.

Following a summer full of equivocation about Reik, Otto Fenichel’s arrival in Berlin signaled the start of lively new programming at the Institute. Fenichel organized and updated the clinic’s record-keeping system (his forte) and launched a group that eventually became the celebrated Children’s Seminars (Kinderseminar). The name of this meeting was attractive but misleading because it was not at all a pedagogical seminar on child analysis. In fact the Children’s Seminars was a special self-sustained course for Berlin’s younger candidates interested in the therapeutic and sociopolitical sides of psychoanalysis. Fenichel first proposed the idea to Eitingon, who agreed to support it, and then pulled together a discussion group much as he had several years before in medical school. Many years later the analyst Edith Jacobson remembered Otto Fenichel as “one of those who maintained their interest in sociological problems.” Edith Jacobson herself would emerge, by the end of the 1920s, as one of the most radical of the left-wing psychoanalytic activists, second only perhaps to the more flamboyant Reich and certainly shrewder. Jacobson was profound and pretty, a smallish woman with intense deep eyes and shiny brown hair brushed back in a loose bun. She always remembered the Children’s Seminars, without reservations, as that “special group [that] tackled the relations between sociology and psychoanalysis.”22 It would be from this circle that Fenichel would develop, by 1931, the inner circle of psychoanalysts specifically devoted to the expansion and circulation of Marxist Freudian thought. The immediate sphere around Fenichel has been described as political left, and correctly so, but claiming that they represented the “left opposition” in psychoanalysis is misleading because individual affiliations were merely a matter of degree.

Political ideologies aside, Eitingon insisted that the clinic’s work could not be called unequivocally “therapy for the masses” for many reasons. First of all, Eitingon intended to remove financial obstacles to individual treatment, not to make psychoanalysis into a charitable cause. Second, the term masses could be conceptually misleading. As Fenichel later explained in his unflinching outline of dialectical-materialist psychology, psychoanalysts do not use the expression “mass psychology” to describe “a ‘spirit of the masses.’” Attributing a universal unconscious to the individual psyche is so inaccurate, Fenichel wrote, that “C. G. Jung had to invent the idea of a ‘collective unconscious’ … which haunts bourgeois psychologies.”23 In contrast, psychoanalysis (even of many) explores how an individual’s unconscious interacts with actual social or environmental conditions; it should in no way be confused with Jung’s sentimental imagery. In practical terms the Poliklinik aimed to provide broadscale mental health treatment outside the medical establishment but still within the parameters of psychiatric practice.

Eitingon was fortunate that he understood the problem of marginalization in all its dimensions. He disavowed the idea that the Poliklinik worked on the “principle of free treatment,” because he feared this concept would marginalize the clinic’s function within an increasingly entrepreneurial state. And he feared that the preening specialists at the Charité would engineer a takeover of his facility. The Poliklinik positioned itself deliberately in contrast to Berlin’s teaching institutions like the Charité where, as Simmel saw it, the “proletariat” and poorly insured people provided material for medical instruction while private “high fee-paying patients” were exempt from such abuse. Simmel tells the story of one of his first patients, a small disappointed woman who wandered away from the Poliklinik muttering “No ultraviolet lamps?” Shy and uncomfortable, she had answered Simmel’s exploratory questions simply: “Yes, they say … I have a problem with my nerves.” Apparently other clinics had dismissed her casually, as a mere annoyance, saying that she belonged to the group labeled “psychopaths” or “neurasthenics.” With Simmel expounding on the “egalitarian character of psychoanalysis itself,” access to treatment could hardly be predicated only on the patient’s ability to pay.24 Treatment decisions were based exclusively on patient diagnosis and need—not on the need of Institute candidates (or Charité medical students) for training material. Since the case’s degree of urgency determined how the patient was to be treated, the diagnosis decided if the treatment would take place at the Poliklinik.

Patients were not stopped from paying for their treatment. They were simply not obliged to pay. Patients were expected to pay whatever they estimated they could afford. People who could not pay, like students, unemployed workers, or indigent men and women, were analyzed free of charge. Since an individual was admitted to treatment on the basis of diagnostic need alone, the mere ability to pay did not determine access to therapy. Patients’ own reports on their financial status were believed: whether they said they could pay or not was not an important factor. The expectation that patients would “pay as much or as little as they can or think they can” (emphasis added) was more important as a practitioner’s clinical issue than as an administrative one.25 The initial consultation fee was about one dollar (in 1926 dollars), with subsequent visits decided on a sliding scale of twenty-five cents to one dollar. Fees were based on a case-by-case assessment of the patient’s, or family’s, income and on “responsibilities,” the term used by the visiting American psychoanalyst Clarence Oberndorf to describe financial obligations such as rent and food. Obendorf’s reports attempted to offer his skeptical New York colleagues a realistic account of how much the applicant could afford for treatment.26

In keeping with its status as a nonprofit private charity, general funds from the Berlin society, patient fees, and private donations maintained the Poliklinik (figure 9). Because all twelve members of the society treated at least one clinic applicant free of charge in their private office, the clinic could carry up to twelve nonpaying patients at a time. Alternatively, society members could donate the equivalent amount of their annual professional income to support the clinic. But even members who chose neither fee-free patients nor extra donations were bound to support the Poliklinik because a system of enrollment was built into the society’s dues structure. In his letter of August 26 to Therese Benedek, a young Hungarian psychiatrist recently settled in Leipzig, Abraham described the requirements for admission to the psychoanalytic society and explained the fees. “The membership dues consist of 8.00 Mark annually for the Steering Committee of the International Association & 200.00 Mark for the local [Berlin] group. The magnitude of the latter dues is explained by the necessity to support the Poliklinik.”27 Actual patient fees, or receipts, covered approximately—and only—10 percent of the Poliklinik’s operating budget. The Poliklinik’s budget provided for salaries, rent, records, upkeep, and management of the facility. The permanent staff members collected small salaries, which, Eitingon commented, “bear no relation to their services or to the sacrifices they make.” For example, the paid assistants each received 75 marks, or $18.00, monthly paid out of the general funds of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Society. Such assets were most likely drawn on Eitingon’s own bank account from which the IPA also received “a new Ψa fund to the amount of one million crowns ($5000).” As Freud was delighted to report, this “put an end to our most pungent fears.”28 Meanwhile the clinic’s own expenses for eight months of 1920 came to 20,000 marks ($5000), with only 2,500 marks ($600) in receipts. October 1920 to October 1921 saw an allocation of 60,000 marks ($14,500) with 17,500 marks ($4,206) in receipts. Historically, mental health clinics with very open policies on access to treatment can be overwhelmed by patients; conversely only this openness of policy lets in patients according to their diagnostic need and specifically not according to their personal ability to pay. In consequence, Eitingon acknowledged, the Poliklinik’s economic independence actually gave clinicians far greater access to patients than private practice.

9 Letterhead from the Berlin Poliklinik’s Stationery (Bundesarchiv, Koblenz, Germany)

Ernest Jones was then in London, enviously watching from afar as the Poliklinik grew in capacity and stature but reluctant to embark on such a project himself. To his friend Jan van Emden, Jones mentioned the Poliklinik’s new funding and also noted the Berlin arrival of two inventive psychoanalysts, “Frau Klein of Budapest [will] analyse children … Sachs [is] analysing a number of doctors who wish to learn Psa and work at the Clinic.”29 Hanns Sachs, a member of the Vienna society since 1909 and coeditor with Otto Rank of the journal Imago, was to remain in Berlin as a master teacher and training analyst until he left for Boston in 1932. Jones would soon bring Melanie Klein over to London and eventually set up the British society’s own clinic in 1926. But in 1920 Jones was still hard-pressed to put aside his objections to a clinic. “We have to think carefully before we throw the aegis of our prestige over an institution that can do psychoanalysis more harm than good in the eyes of the outer world,” he wrote to his colleagues in Vienna and Berlin.30 He found the recent spread of “wild analysis” alarming, despite the Berliners’ campaign to offer all new practitioners professional training, and he thought that “the relation between medical and lay workers [wa]s the exact opposite of what it should be.” For Jones, nonmedical (or “lay”) analysts had never really held the same level of clinical authority as physicians. Although Jones constantly invoked Freud’s authority in psychoanalytic matters, he contested the belief that a medical education was fundamentally not beneficial (and might even hinder) effective psychoanalysis. He admired Brill’s conservative exclusionary stance in New York. “I have not been so unsympathetic to the American point of view on lay analysis as most people in Europe,” he later wrote to Eitingon. “I am even inclined to think that I should share it if I lived in America.”31 Despite his faith in Freud and his contempt for Americans, Jones took their side in the struggle to maintain medical dominance of the profession. No wonder then that the psychoanalyst Barbara Low’s repeated offer to investigate the Berlin clinic on behalf of the British society was deferred for at least a year. Barbara Low was a friend and colleague of Alix and James Strachey and their Bloomsbury literary group. In the mid-1920s Alix and James would become Freud’s master translators and would travel back and forth between London and Berlin for their analyses. Low was consequently comfortable with Berlin but her resolution, “that an enquiry into the organisation, financial and otherwise of the Berlin Psycho-Analytic Clinic be made as soon as possible with view to establishing a Freudian clinic in London,” was tabled.32 Four years later Low finally went to Berlin, and her report on the Poliklinik became the blueprint for the London Psychoanalytic Clinic. Jones, a physician, would become its director.

That July, although the Berlin Poliklinik opened with no apparent governmental hurdles, the project for a clinic in Vienna was much more cautiously received. Eduard Hitschmann, one of the unsung heroes of psychoanalysis and a forceful Social Democrat, insisted that psychoanalysts should have a free clinic and he battled Vienna’s entrenched medical and psychiatric establishment in its pursuit. For two more years, until 1922, Hitschmann encountered governmental obstacles to opening the Ambulatorium. Few analysts were in a better position than Hitschmann to act on the Vienna society’s interest in a free clinic. Respected by his peers as a “model of order and exactness in all his work and skill” and a great psychiatric diagnostician, Hitschmann seemed to relish confronting the starched medical bureaucracy all the same.33 Competitive and energetic, and personally needled by the news of Max Eitingon’s immediate success at the Berlin Poliklinik, Hitschmann was determined to organize a similar outpatient clinic. Most of the Vienna analysts were predisposed to start a free clinic. Their traditional medical ethos encouraged free services; they felt they should join with the new movement; and their self-interested motivations to gain legitimacy and build their practices were equally strong. “Every branch of medicine had a free clinic. So it wasn’t so unusual for the socially-minded psychoanalysts to decide that we should have one too” said Martin Pappenheim’s daughter Else, who emigrated under duress in 1938 while still a psychoanalytic trainee.34

In the end the Ambulatorium was shaped largely by Hitschmann’s own abilities, but it was also determined by Paul Federn and Helene Deutsch’s active socialist concern for the city’s lower classes.35 Yet, curiously, the beginning of the Vienna Ambulatorium was marked by distrust on all sides. Hitschmann’s petitions for the establishment of a psychoanalytical outpatient clinic in the name of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society were rejected both by the State Medical Department and the Municipal Council of the Medical Staff of the General Hospital. Unfortunately, even the new social democratic government drew a distinction between physical health and mental health and hesitated before granting psychological illness the same protections as tuberculosis and dental hygiene. Nevertheless, the galling resistance Hitschmann encountered over two years as he readied the Ambulatorium was directed far less at the free clinic as an institution than at psychoanalysis as a treatment method. Just as Freud had predicted in his Budapest speech, public support of their clinic would lag behind the psychoanalysts’ own private charitable initiative. But Freud, who had raved about the opening of the Poliklinik in Berlin just eight months earlier, grudgingly wrote to Ferenczi that he “would basically be done a favor if [the clinic] never came into being. It is not suitable for Vienna.”36 He also suggested to Karl Abraham that the Vienna society’s application for a psychoanalytic section at the general hospital went totally against his wishes. “Getting it would be quite unwelcome for me,” Freud wrote, “because it would have to be in my name; I cannot devote any time to it, and there is no one in the Society to whom I could entrust its management.”37

Freud’s ostensible retreat from his 1918 Budapest manifesto followed a complex and interesting dynamic. The governing ideology of Viennese political culture was now unmistakably social democratic and Freud could afford to show a more reactive political side. On a personal level he felt burdened by old age (at sixty-four) and wary of increased workloads and managerial tasks intruding on his practice. He bemoaned an apparent dearth of independent leadership among the Viennese analysts. Vienna’s psychoanalytic society lacked skilled administrators like Eitingon and even Jones, a situation perhaps created by Freud’s preeminence but obvious nonetheless. On the political level, and in contrast to his earlier proactive demand for free psychoanalytic clinics, Freud was fearful of seeing psychoanalysis co-opted entirely by the left now that Vienna’s leftward shift had been accomplished. He would hardly want the municipal government to legitimate their civic goals by exploiting his work. Freud needed to stay left of the right-wing party since the Christian Socials were openly anti-Semitic, but he also sought to stay clear of overt political commitment. It was a composite posture Freud would repeat periodically throughout his life as he sought to keep psychoanalysis above the political fray.

The Viennese psychoanalysts of the 1920s represented the entire political spectrum of the left, from Social Democrat to Communist. The fact that some moved far to the left does not mean that others were far to the right. “Most of the intellectuals, what here [in the United States] is a liberal was a socialist, a Social Democrat in Vienna” explained Grete Lehner Bibring.38 Wilhelm Reich moved eventually to an even more radical left-wing position and openly took to the Communist Party. But other analysts like Paul Federn thought that Communists were hazardous to the nascent psychoanalytic movement, not because of their ideology but because they were subject to arrest or police supervision and could be relieved of their party affiliation if discovered in analysis. Social Democrats, on the contrary, were people like himself. With a mother who advocated for women’s rights, a father whose practice as a family physician tended to the poor, and a sister who founded the first private social work agency in Vienna, the Vienna Settlement, Paul Federn epitomized the social democratic brand of progressivism. So it was important to distinguish between “Communist” as a political party affiliation and “Socialist” as a nominally Marxist political ideology aligned with the Social Democrats.39 Sigmund Freud often repeated his opposition to Communism per se. But that was a different party; and the psychoanalysts remained, Freud and Grete Lehner Bibring included, “all social democrats because that was the liberal party for us.“40 The younger generation of Viennese analysts was deeply attached to the Austro-Marxists in city hall, while Freud and the older analysts with values grounded in a classical liberal tradition, simply identified with them.

Nonetheless, the twin beliefs that psychoanalysis had an implicit political mission and that Freudianism was progressive were widely understood by its practitioners, by the Social Democrats governing Vienna, and within at least the more avant-garde intellectual circles in Europe and America.41 Emma Goldman, the American anarchist, had been “deeply impressed by the lucidity of his mind and the simplicity of his delivery” at Freud’s 1909 Clark University lectures. Goldman recorded in her autobiography, Living My Life, how his speech echoed for her the themes of female sexuality and release from oppression she had first heard from him in 1896. Freud and psychoanalysis officially landed in America in September 1909 at Clark University’s Twentieth Anniversary Conference held in Worcester, Massachusetts. Invited by the psychologist G. Stanley Hall to receive an honorary degree, the initially reluctant Freud was accompanied across the Atlantic by Carl Jung and Sándor Ferenczi. Freud improvised in German and delivered five lectures, each one developed around a specific psychoanalytic discovery. The final lecture explored how “civilization” demands repression and applies a particularly stringent moral code to the “cultured classes.” America’s ethic of puritan morality exemplified, for Freud, the repression inherent in civilization’s moral codes. Challenging the somatic style then widespread in American psychiatry, Freud’s ideas were ambiguously received. Nevertheless, the 1909 lectures represented a watershed in American behavioral and social sciences. For the neurologist James Jackson Putnam, the visit “was of deep significance,” while the Harvard psychologist William James, the psychiatrist Adolph Meyer, and the anthropologist Franz Boas were more ambivalent.42 The newspaper and magazine press alternately lionized and deplored him, setting the tone for a tense, unsettled relationship that lasts even until today. American resentment of Freud still lingers in many ways, but the feeling has always been mutual. Even in the mid-1920s Freud tried to avoid American questions about socialism and other controversial opinions, saying “politically, I am just nothing” to the Greenwich Village journalist Max Eastman, who had earlier published a book on Freud and Marx. At the same time, Freud advised Eastman that Lenin was carrying out “an intensely interesting experiment,” rational enough for his serious scientific side, but anarchist enough to be accepted by some brilliant young analysts like Otto Fenichel and Wilhelm Reich.43 Eastman was hardly dissuaded of Freud’s progressivism.

Certainly by 1920 Freud was comfortable with current social democratic politics. As he told Ferenczi, he was delighted to receive an invitation to join Mayor Jakob Reumann’s committee, headed by Red Vienna’s guiding public health reformers Clemens Pirquet and Julius Tandler, to oversee an international child welfare fund.44 Baron Clemens von Pirquet, who joined Freud and Tandler’s child welfare project, was one of those extraordinarily inventive figures of début de siècle Vienna. A distinguished-looking pediatrician described as “exceedingly kind and polite though very nervous” by his laboratory’s funders from the Rockefeller Foundation, Pirquet also introduced the concept of allergy into current medical language and pioneered modern nutrition with a system of measurements based on units of milk.45 He was close to many of the psychoanalysts, among them Helene Deutsch, just finishing her term as a war psychiatrist and interested in childhood mental health. In some respects the project fit neatly with the Social Democrats’ overriding interest in rebuilding Vienna around a core of child- and family-centered public welfare and their need to make constructive use of foreign moneys. In other respects, as Richard Pearce correctly observed, antagonism between Tandler and Pirquet, “the former representing the socialistic point of view and the latter the aristocratic,” led to clashes over resources at the University of Vienna.46 By the time Pirquet joined the American campaign of aid to Austrian children, the Commonwealth Fund had decided to help his famous Kinderklinik expand and repair its convalescent home for tubercular children. Several special grants helped replace worn-out technical equipment and surgical instruments used especially for operating on children. Subsequently Freud’s wealthy and philanthropic brother-in-law Eli Bernays, now living in the United States, added a million crowns to the three-million-crown grant ($608,000) from a group of American physicians keen on building up Vienna’s medical infrastructure including children’s convalescent homes.47 With images of the war’s human wreckage still fresh, the Viennese decision to accept grants, even if preferential, from wealthy Americans was easy. The Americans, however, were responsible for administering these bequests morally and fairly. Notable among the foundations that chartered the course of modern child welfare and child development research, the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial (LSRM) responded enthusiastically to the idea that cultivating good mental hygiene in childhood would produce healthy adults. According to most developmentalists including Freud, human character, personality, and even individual physiology are most vulnerable to environmental influences in childhood. A peaceful and productive postwar society would therefore be in want of attentive, progressive early education and social services dedicated to children’s welfare. For the moment the LSRM was ready to invest directly in Julius Tandler’s practical social services.

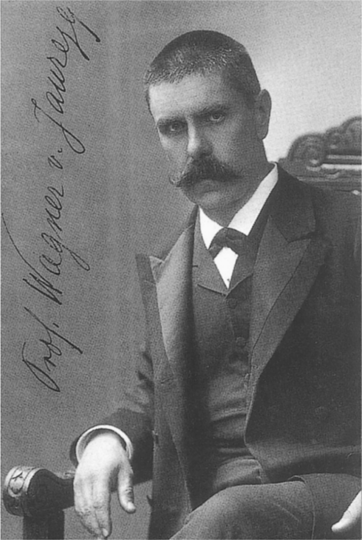

Freud was considerably more ambivalent toward other prominent Viennese doctors who were not affiliated with the Social Democrats. Among them the neurologist Julius von Wagner-Jauregg (figure 10) was then director of the city’s principal public psychiatric clinic and, in 1920, as well-known a psychiatrist in Vienna as Freud. A thin man of dour appearance, Wagner-Jauregg’s severe demeanor was underscored by a downturned mouth, a large waxed moustache, and a closely trimmed crewcut. Compassion was hardly his forte, but he was nevertheless an inspiring teacher and a formidable researcher who would be awarded the Nobel Prize for his 1927 discovery of malarial therapy for general paralysis. Nevertheless, in 1920 Wagner-Jauregg was charged by the city government’s Commission of Inquiry on Dereliction of Military Duty with the lethal use of electrotherapy on shell-shocked soldiers. The commission, made up of prominent Social Democrats, invited Freud to testify as an expert witness at the October 14 and 16 hearings, where they investigated allegations of torture by military psychiatrists under Wagner-Jauregg’s purview. Since 1918 the Arbeiterzeitung and other newspapers had published gruesome personal accounts of how the soldiers, suffering from war neurosis but accused of malingering and lack of will, were tortured in Wagner’s clinic with “faradization” or electrical current to the point of death or suicide. Still a Hapsburg loyalist, Wagner-Jauregg joined patriotic duty to medical power and ordered isolation cells, straitjackets, and selective burning as therapy for soldiers he considered insufficiently energized for the war effort. But psychiatric brutality, even when passing as duty to the nation, simply outraged Freud. The psychiatrists had “acted like machine guns behind the front lines, forcing back the fleeing soldiers,” Freud said on the stand.48 Furthermore, he changed the tone of his written “Memorandum on the Electric Treatment of War Neurotics” from a clinical paper into a political statement. He began the essay as a diplomatic colleague would, suggesting that Wagner-Jauregg was a man of principle who had acted against his better psychiatric judgement because of civic commitment to the interests of the state. While both men agreed on the symptomology underlying war neurosis, they disagreed on the treatment. But Freud ended with a withering critique of war and traditional military psychiatry. Conscription was not the patriotic duty of the state, he said, but the opposite, the “immediate cause of all war neurosis, [forming] rebellion against the ruthless suppression of [the soldier’s] own personality by his superiors.” Wagner-Jauregg’s willingness to act in concert with the corporate state, by implicitly supporting governmental use of violence, dishonored the physician’s humanitarian concern for the individual.49 Freud had told Ferenczi that he would “naturally treat [Wagner-Jauregg] with the most distinct benevolence,” adding that the events had “to do with war neurosis.”50 He had only wanted to show the court how their clinical and theoretical approaches differed without attacking his colleague personally. Just then the Viennese psychoanalytic society was formulating plans for its own free clinic, and Freud knew that the project would require at least nominal diplomacy toward his conservative rival. Wagner-Jauregg was eventually exonerated, but he continued to represent for Freud Vienna’s old-time medical establishment and the dominance of a reactionary punitive stance in psychiatry.

10 Dr. Julius Wagner von Jauregg (Institute for the History of Medicine at the University of Vienna)

All too soon, however, Freud found his courtesy to Vienna’s institutional psychiatry and Wagner-Jauregg outmaneuvered. Hostile functionaries and a lethargic medical bureaucracy blocked Hitschmann’s proposal for the Ambulatorium at each turn over the next two years. Since the license to open the clinic remained in the hands of the medical community’s conservative opponents of psychoanalysis, Hitschmann enlisted the backing of his physician colleague Guido Holzknecht. Highly respected as a leading radiologist of the time, assistant in Hermann Nothnagel’s clinic, and connected with the governing Society of Physicians of the Allgemeines Hospital, Holzknecht had also been since 1910 a member of the Viennese psychoanalytic society.51 Holzknecht, Freud, and Hitschmann were friends and partners, jointly convinced that investigation of the unconscious mind and the interior body have equivalent aims. Holzknecht’s genius in discovering tumors was the physiological counterpart to Freud’s detection of the neuroses. Holzknecht and Freud also found themselves associated as reciprocal doctors and patients: Holzknecht, a former analysand, was the radiologist who treated Freud’s cancer in 1924, and in 1929 Freud visited Holzknecht, who was dying of cancer from his own experiments, his right arm already amputated. Freud said, “You are to be admired for the way you bear your fate,” and Holzknecht replied, “You know I have only you to thank for that.”52 Clearly, Hitschmann had found an influential spokesman and strategist.

Yet two full years of carefully planned tactical maneuvering would go by before the Allgemeines Hospital would officially designate an approved section for the Ambulatorium. Holzknecht’s first personal intervention with the administration seemed to go well. On June 16 he optimistically noted his first auspicious visits to department heads and wrote to Hitschmann that “there would be room in the next months for an ‘Ambulatorium for mental treatment’ at Garrison Hospital No. 1. But how to commence? With whom to begin? I think eventually by association with one of the sections at the general hospital, though unfortunately it’s impossible at mine. (Then again, nothing is really impossible!)”53 Hitschmann followed his colleague’s optimistic advice. Barely five months after the Berlin clinic opened, his petition dated July 1 was in the hands of the Senior Physician’s Council of the Allgemeines Hospital, the local Public Health Authority of the State Medical Department, and the Society of Physicians headed by Wagner-Jauregg. The psychoanalytic Ambulatorium, Hitschmann promised, would not compete with the psychiatry department for patients nor decrease the use of medical therapy but instead would supplement other forms of treatment. Psychoanalysis could hardly be viewed as rivaling other departments of the hospital, “since psychotherapy, let alone psychoanalysis, is practiced at none.” It had been inaccessible to the “wider masses until now” but was “ready for practical application on a broader scope. The Ambulatorium would restrict itself to underserved sick persons.”54

An impressive red brick building housing the Military Hospital (Garrison Hospital No. 1) was selected for the Ambulatorium’s location because of its convenient proximity to the General Hospital and because some of its treatment rooms had lain empty since the end of the war. These facilities could be put to use quite efficiently, calculated the psychoanalysts, since they would need at most a waiting room, another large area in which to examine prospective patients, and several small treatment rooms. Modest requests perhaps, but the hospital’s branch of the Society of Physicians—the governing body of the Austrian medical profession—was in charge of allocating the facilities and saw no need to step up their unhurried decision-making process. Holzknecht, a member of that council (along with Wagner-Jauregg), relayed to Hitschmann, his friend and “most esteemed colleague,” some confidential reports and instructions for future action: “Our proposal was not raised at the first meeting of the hospital’s Physician’s Council. I have done nothing about this, in order not to be identified as partisan from the outset. I urge you to visit the director Dr. Glaser and, without pushing too hard, to inquire about the fate of the oft-submitted proposal, so that it does not vanish into the bureaucratic black hole.”

Uninspired negotiations continued. For no clear reason, the hearing on Hitschmann’s petition was switched from the hospital’s local Physician’s Council to the October meeting of the State Medical Board. As the doctors filtered out of that inconclusive session, Holzknecht stood around chatting sociably when suddenly the board’s secretary alerted him that doctors Wagner-Jauregg and Jakob Pal were ready to listen to him. As “I read to them the introductory words of your proposal,” Holzknecht reported on the events of October 23, Jakob Pal, a professor of internal medicine and also a board member, interrupted and nominated Wagner-Jauregg to examine the plans and deliver an expert opinion. The entire council agreed, unanimously. It was “the Austrian way,” Holzknecht said dejectedly to Hitschmann. This time nothing could be done but to press Wagner.55 And so the aristocratic Wagner von Jauregg, presumably still smarting from Freud’s appearance at his trial, took the entire following year to examine the document, exercise his jurisdiction, and eventually come to an interim decision in July 1921.

In contrast to the sluggish progress of the psychoanalysts’ petition for a free clinic, other branches of Vienna’s new public health department moved forward rapidly. In November 1920 Julius Tandler was named councillor in charge of the Viennese Public Welfare Office, a post he maintained energetically until February 1934. Tandler saw a state- and community-based welfare program as the most expedient and viable remedy to Vienna’s widespread postwar deterioration in almost every aspect of human life. In line with the cultural evolution of Red Vienna, a thorough reorganization of the health and welfare structure was called for and Tandler, working with Hugo Breitner, Otto Glöckel, Karl Seitz, and other Social Democrats, became its principal architect.

Tandler’s theories proceeded from earlier models of social welfare benefits and entitlement like Bismarck’s large-scale programs of domestic health, accident, and old-age insurance. In a curious ideological contradiction not unusual in nineteenth-century politics, Bismarck’s progressive programs stemmed from a conservative motive, to create distance between German workers and the socialist movement—though it had the opposite effect. Like Bismarck but differently motivated, Tandler sought to bind workers to the state and vice versa. “In Germany,” he wrote, “10–15% of all children born alive are provided for under the welfare system; in Austria the numbers are barely 4–5 in a thousand.”56 He wrote this admiringly, not because he believed that the state should override parental responsibility in taking care of so many children but because, by doing so, the state could prove its capacity to care for children whose lives had been placed at risk by larger social and environmental conditions. In Vienna a crippling environment had been created by the war. Tandler responded by centralizing all the city’s welfare institutions into a single Public Welfare Office with professional and legal controls. His first concern, to curtail the patronizing policies of “Poor Care” charity by replacing them with modernized, planned, and far more respectful forms of direct assistance, led to further administrative reforms. Tandler’s particular focus on the needs and rights of children corresponded, just then, to the emergence of new scientific studies of child development and new treatment techniques, as well as early childhood education and child analysis, all of which implied the necessity for social welfare services. The psychoanalysts agreed. The Ambulatorium, they believed, would shift free mental heath treatment from a stigma-laden paradigm of charity to that of social service.

Vienna’s postwar social services offer a virtual map of the advances made by modern social work practice from the 1900s, when it was largely the province of upper-class benevolence on moral patrol, to the 1920s, when it grew into an educated profession. In Red Vienna some of the most powerful funders of social work and international social welfare, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Commonwealth Fund, collaborated with the city’s health care leaders including Julius Tandler, Clemens Pirquet, and Guido Holzknecht. The Rockefeller Foundation’s representatives watched Tandler’s politics with some ambivalence but in general agreed with his goals. His sympathy for psychoanalysis was well-known, as was Holzknecht’s, and they influenced every major social welfare campaign of those formative years. With international funders, city leaders, and local psychoanalysts united in support of progressive child welfare policies, the new profession of social work assumed its respected position within the welfare state.

Within each of Vienna’s districts a woman appointed as a “welfare officer” visited the homes of children placed in care of families other than their biological parents, adopted children, and children born out of wedlock. She worked at the mother’s advisory centers in residential areas and oversaw school medical inspections, looking out for family problems and signs of potential physical or sexual abuse. Supplied with extra cash, she could supplement a family’s need in small ways, buying clothing or a pair of shoes for a child or new equipment for a father about to lose his job because he lacked masonry tools. Of course she documented her observations of the child’s living conditions: the very nature of her work was defined by the successful coupling of practical assistance with the university’s most current methodology, the direct observation of children’s behavior. The core motive of a social worker was (and is) always subject to interpretation, and allowing her into the family home meant relinquishing jurisdiction over its members to the allegedly controlling state. But the opposite motive can also hold true, and a government can be more interested in assuring the safety and welfare of its children than upholding the false dignity of traditional family structures. As Tandler would reply to the Christian Socials’ accusations that social workers took children away from families, “I can only say that we are doing our utmost to leave these children with their families in every possible case. But … the first thing we have to ask ourselves is whether the parents are really capable of bringing up their children.”57 In any society that sets great store by the idea of privacy, family home visits are experienced as intrusive and humiliating unless perhaps a medical emergency requires a physician at the patient’s bedside. If patriarchal monarchist Austria asserted the supremacy of parental authority, then the welfare policies of Red Vienna affirmed the state’s right to protect the child.

Given the Viennese preoccupation with child protection and Julius Tandler’s own belief in the value of specific family-based assistance, the government standardized and strengthened the ties between the public child health centers and the supportive services provided in the home. New opportunities for teaching young mothers, not necessarily about sanitation, which was already quite good, but about nutrition and breast feeding or the treatment of fever and infection, led to the creation of a new occupation: the Fürsorgerin. Midway between a nurse and a social worker, but more influential than both combined, the title of Fürsorgerin had no actual counterpart in the United States. The Fürsorgerin’s impressive stature came from a largely centralized health and social work system that placed responsibility for child care squarely with the government and therefore could normalize approaches to child welfare issues such as illegitimacy, orphanhood, and abuse and neglect of children. As a social worker, she (for it was largely a woman’s profession) could count on the law to support her decisions, and, as a public health worker, her judgment was respected for the medical weight it carried. Trained Fürsorgerinnen were assigned, county by county, to assist physicians at the prenatal or child health stations as well as the families living in their geographic catchment areas. “Stations are found in all sorts of public and semi-public buildings—hospitals, town halls, store buildings, and municipal tenements which,” the authors of the Commonwealth Fund’s report declared of the Gemeindebauten dwellings, “are apt to be delightfully modern in style and decoration!”58 Young children would not be deprived of care even if their overburdened mothers lacked the time for pediatricians. Instead mothers saw the Fürsorgerin in her rounds of home visits, reviewed the children’s health, learned some safety tips, and procured some relief from the depressing load of everyday domestic life. Of the one hundred federally subsidized child health stations in Austria, the fifteen centers located in Vienna enrolled almost ten thousand and assisted another forty thousand children. In the year 1927 alone the Fürsorgerinnen affiliated with the health stations made over sixteen thousand home visits to enrolled infants and preschool children in Vienna.59 True, the Fürsorgerinnen searched out parentless children or supervised the care of foster children as required by law, but mostly they referred children needing orthopedic or dental care to special clinics, or for tuberculosis to the health station, or for mental health care to the Ambulatorium.

The class clowns and the constant talkers, the cheaters and the liars, impudent or vain children, kids with poor grades, some depressed and some caught masturbating, by all accounts most of the children seen at the guidance clinic, were demoralized by family troubles. The entire municipal school system was now reorganized by the postwar Austrian Board of Education to regard children’s social adjustment as important as their instructional needs. The choice was between Freudian or Adlerian pedagogy, but each group’s allied educational institutions were imbued with psychoanalysis. Shaped by Willi Hoffer and Siegfried Bernfeld’s kindergarten designs and by Alfred Adler’s trademark Individual Psychology, the new Pedagogical Institute for the City of Vienna was simultaneously affiliated with the philosophy faculty of the university and with the Vienna Psychological Institute of Karl and Charlotte Büehler. The Büehlers, then Vienna’s leading academic psychologists, were fine-tuning their methodology of laboratory-based, controlled experiments to understand child behavior. And when Adler spoke at the Pedagogical Institute, he enlisted a wide forum of educators, therapists, and school superintendents in the first program for teachers of child guidance clinics. He was personally engaged in setting up the first of what would eventually become an entire network of teacher and child guidance clinics. In a city district with sixty-seven grammar and high schools, 171 of the area’s almost 20,000 children were voluntarily treated in 1920 (the first year of the program) on a case-by-case basis.60 Most teachers had never considered problem students to be an organic part of the classroom, nor ever thought of them as depressed or isolated. Now Adler’s method trained teachers to involve the entire classroom in building up the sense of Gemeinschaftgefuehl, or community feeling, among truant or rude children. Troubled children had bad problems, not innately bad character.

When Otto Glöckel, head of Vienna’s reform-minded Department of Education in charge of school administrative policy, resolved to officially support Individual Psychology, Adler was finally afforded the chance to test his ideas in practice. The building at 20 Staudingergasse, one of the city’s oldest classical structures, was remade into an experimental grade school based on Adler’s principles of Arbeitschule, work and community. Spacious communal rooms were refashioned from once ornate chambers. Old wood benches, lockers, and even small metal inkwells were salvaged from the military and distributed to local children, most from poor families. Psychodrama, group talk, and individual therapy were used as educational tools in this extraordinary school setting where children themselves became coeducators, assistants, and hopefully cotherapists for their more disturbed classmates. There Oskar Spiel and Ferdinand Birnbaum incorporated depth psychology into the daily class agenda, providing modern progressive education for the next ten years to countless neglected, neurotic, learning disabled, or simply underprivileged children. Parents from the school’s working-class neighborhood received the Adlerians’ little illustrated journal Elternhaus und Schüler (Parental Home and Student) and free evening classes in child development. Glad to abide by the curriculum of the new Austrian elementary school, Spiel and Birnbaum tried to bridge the gap between individual psychology and psychoanalysis (a bridge Adler and Freud had failed to build) and strove for an intensely therapeutic atmosphere where every class was a community experience. Freudian psychoanalysis, emphasizing the inner self over against social determinism, also played its part in validating the individual child’s right, as separate from the family, to be protected by the state.

Concurrent with this reorganization in conventional social values and gender roles, a sexual revolution seemed to flourish on virtually every level of society. Women were voting. Sexuality was openly discussed in popular newspapers and novels like Hugo Bettauer’s Wiener Romane. Bettauer, a prolific Austrian writer whose novel, The Joyless Street, was made into a film by G. W. Pabst in 1925, would reappear throughout the early 1920s as a popularizer of psychoanalysis and a veritable champion of the Ambulatorium. Meanwhile the ambiguous idea of the procreative family, promoting at once maternalist and feminist images, imbued everyday life from urban transportation to municipal architecture. The student seminar on sexology started the year before in 1919 by Otto Fenichel and his friends Reich, Lehner, and Bibring was therefore hardly out of place, either within the university or outside of it. Now in its second year, the seminar planned to explore how traditional beliefs about sex could be retooled with the new psychoanalytic methodology and how to extrapolate a political agenda therefrom. For Fenichel, sexual freedom was as much a political issue as a psychological one. “Does man live from within or without?” was the anarchist title of an experimental symposium of June 22 in which he demanded outright that the participants give voice only to their feelings and resolutely expel all intellectual or scientific thoughts. Somewhere between a sermon and a harangue, Fenichel’s highly charged two-and-a-half-hour speech explored a range of systematic yet humane solutions to social problems. Are science, philosophy, the youth movement, or politics best for mobilizing people to alleviate humanity’s “great, glaring misery in all its colors?”61 The company that night at his friend Hans Heller’s elegant apartment included Reich’s study partner and friend Desö Julius, a Hungarian student who had escaped to Vienna that summer after the fall of Béla Kun’s government and who introduced Reich to the communist movement. Otto Fenichel’s girlfriend Lisl was there along with his own sister and brother-in-law, Paul Stein, as well as Gisl Jäger from the Youth Movement, Gretl Rafael and Willy Schlamm, future publisher of Die Rote Fahne (The Red Flag) in Vienna. Annie Pink, who would become Reich’s first wife and a prominent psychoanalyst, was there as well, still a member of the Youth Movement and a high school student. So too was Lore Kahn, a kindergarten teacher in training and Reich’s pale sweetheart. Kahn died soon afterward of tuberculosis. When her grief-stricken mother falsely accused Reich of inducing Lore’s death by causing her to have a disastrous abortion, Reich referred the mother to Paul Schilder, then professor of psychiatry at the University of Vienna.62

Different as they were, both Paul Schilder and Heinz Hartmann (the future champion of ego psychology) had worked at the university’s psychiatric hospital but saw little if any contradiction between Freud’s psychoanalytic and Wagner-Jauregg’s organic biological views of mental illness. Wagner-Jauregg presided over the Psychiatric-Neurological Clinic, Vienna’s center of clinical psychiatry, and most days were still filled with his research protocols based on electrotherapy and insulin shock treatments. Even Helene Deutsch, a military psychiatrist during the war, had worked on his experiments in round-the-clock shifts. Since women were precluded from official appointments, Deutsch lost her job when Schilder came back from the front, but she recognized in him “a very original and productive spirit” and seemed not to resent the institutional insult.63 Deutsch used some of Schilder’s experiments with humanistic hypnosis to draw out, for example, an elderly catatonic woman, intuiting that just behind her patient’s blank façade a hidden consciousness was listening and inviting human contact. Evidently by the early 1930s most of the young analysts at the Ambulatorium were encouraged to study Schilder’s model. Erik Erikson (then still using the name Erik Homburger), who had attended some of Tandler’s classes, pursued further studies in psychiatry with Schilder. Paul Federn maintained friendly connections to the university clinic and later found that the application of psychologically based therapy to psychosis was invaluable. The clinic itself was not far from the Freud home on Berggasse, and Anna Freud attended afternoon training sessions while Deutsch was an assistant. In Anna’s tightly controlled background as a grade school teacher, little had prepared her for the spontaneous outbursts and unmitigated pain of the psychiatric patients. But Anna learned quickly. She watched her friend Grete Lehner Bibring, also a pupil of Schilder’s, apply his integrated model to her very first analytic patient, a prostitute with a compulsive neurosis. Grete had graduated from medical school at age twenty-four and started a psychiatric practice right away. Even after two years of experience at Wagner-Jauregg’s clinic, Grete still looked back on Schilder’s training as the best preparation for handling the florid psychiatric symptoms of, for example, a delusional, twenty-three-year-old polymorphously perverse clinic patient. Nonetheless, ten years were to pass before Schilder formally brought medical psychiatry to the Ambulatorium with the brilliant but short-lived Department for the Treatment of Borderline and Psychoses.

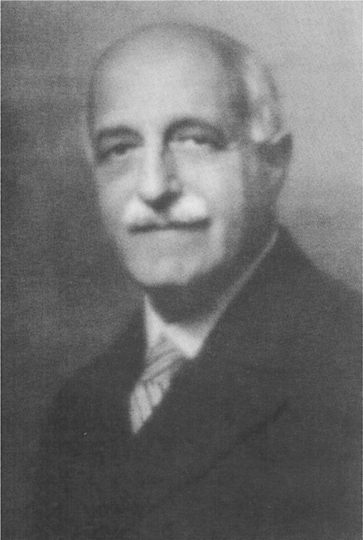

Meanwhile, on the main campus of the University of Vienna, the seminar in sexology grew ever more popular. After Fenichel had left Vienna for Berlin that fall, Reich assumed chairmanship and administrative responsibility for scheduling lectures and conferences. His outspoken interest in human sexuality was reflected in his choice of program speakers like Isidor Sadger (Reich’s own analyst), then researching homosexuality and sexual perversions, and Eduard Hitschmann (figure 11), who was publishing studies on female frigidity. Reich’s experience with authoritarian structure bred by four years in the military soon led him to divide the seminar into two branches, a biological group headed by Eduard Bibring and a psychological group, his own. The events were so popular, Reich reported, that thirty students and supporters turned out for a fairly plain lecture on “Drive and Libido Concepts from Forel to Jung”.64 As attendance grew, Reich encountered eager groups of radicalized university students, among them Fenichel and Bernfeld’s old friends and followers from the Youth Movement as well as young adherents to the Social Democratic Party. Soon what had started as a simple extracurricular activity at the medical school became a planned program of seminars for the study of sexology. Endocrinology, biology, physiology, and especially psychoanalysis were studied as new branches of the new discipline.

11 Eduard Hitschmann (Institute for the History of Medicine at the University of Vienna)

Among the occasional seminar participants who would eventually join Reich at the Sex-Pol clinics was Lia Laszky, a fellow anatomy student of Tandler’s at the University of Vienna medical school. Lia was an elegant young bisexual woman with whom Reich was so obsessively infatuated and tormented he felt he might “wind up with Jauregg”. Lia had a “soft face, a small nose and mouth, blond hair,” Reich remembered, and, though poor, she thrived on Vienna’s festive vie de bohème.65 She lead Reich to Vienna’s modernist music and opera and followed up their discussions about socialism with gifts like Gustav Landauer’s book, Aufruf (The Call). Reich took to Landauer and Sterner’s utopianist views immediately. Critics, then as now, have dismissed Reich as overidealistic and anarchist, yet his effect on psychoanalysis is almost unrealizable, and much of its impact lies in his clinical application of Landauer’s ideas. Similarly, when Reich gave Lia books on psychoanalysis (like Hitschmann’s) and personally intervened to secure her psychoanalytic education, she shifted her involvement away from the Wandervogel and sought to organize a left-leaning Youth Movement group for girls. More familiar names were to join Reich’s subsequent efforts to organize Sex-Pol—Annie Pink Reich, Edith Jacobson—but, among his friends in the second generation of psychoanalysts, Otto Fenichel engaged most boldly with political activism.

Otto Fenichel was clearly a born orator and, when he returned to Vienna from another stay in Berlin that Christmas of 1920, he enthralled his friends for two full evenings on the subject of “On Founding a Commune in Berlin.” Most of the members of the sexology seminar had heard about the Berlin Poliklinik though few except Fenichel had actually visited. But it was Fenichel who actually foresaw the many ways in which the Berlin Poliklinik would become, as Freud put it, an “institution or out-patient clinic … where treatment shall be free.” He was fascinated by the Berlin model, the first and for the moment the only one of its kind, which formed a social nexus between the Poliklinik as a clinical service and the Institute as a regular psychoanalytic training program. The composite institution met Fenichel’s expectations for collectivity, an interest that would dominate his personal and professional life.

In Vienna Freud and Rank announced in a circular letter to their colleagues that they would publish a year’s end report on the activity of the Berlin clinic, either in brochure form or as a supplement to Imago, even before the real work of treating patients had started.66 In Weimar Berlin and Red Vienna the idea that creativity could be blended with everyday practicality had particular intellectual and popular appeal.