“The honor proceeds from the Social Democratic Party”

BY 1924 fewer and fewer citizens of Red Vienna believed that psychoanalysis was either an arcane science or a dependent stepchild of psychiatric medicine. After the war the public’s interest in psychoanalysis “actually moved faster than that conservative corporation, the medical profession,” Paul Federn wrote, and medical patients demanded psychoanalytic information, referrals, and advice from their doctors in virtually all areas of specialization.1 But the role of securing even greater popularity for psychoanalysis fell to Siegfried Bernfeld, who organized a special Propaganda-Komitee (publicity committee) for this purpose. “His fascinating personality, sharp sense and powers of oratory,” Freud wrote of Bernfeld to Jones, made for a particularly imaginative leadership of a group from the Vienna society that required little to mount a creative public campaign around the city.2 They sponsored lectures at municipal cultural centers like the Ärzte-Kurse, a continuing education program for doctors, the university’s Internationale Hochschulkurse (international studies school), and the Academic Society for Medical Psychology. There were also courses at the American Medical Association of Vienna, the Volksbildungshaus “Urania” (a popular education project), the Volkshochschulen (adult education courses), and a range of societies for women’s and for workers’ education. Felix Deutsch, Josef Karl, and Paul Schilder lectured at the university itself. Every few months August Aichorn, then chairman of education for the State Juvenile Department, discussed the application of psychoanalytic theory with directors of various child care institutions, schools, and clinics. These psychoanalytic events were reviewed more often in the press, and the public link between Freud’s name and the governing Social Democrats grew stronger. The Viennese Social Democrats honored this bond and decided to reward Freud on his sixty-eighth birthday with a high-profile civic tribute of Citizenship of Vienna.3

The special distinction that city leaders offered Freud had to do with the Social Democratic Party—specifically the complementarity between psychoanalysis and the party’s governing ideology. Freud was quite pleased. “This recognition is the work of the Social Democrats who now rule City Hall,” he wrote to Abraham in early May of 1924.4 “I have been informed that at midday on the sixth,” he continued, “Professor Tandler, representing the burgomaster, and Dr. Friedjung, a pediatrician and a district councillor, who is one of our people, are to pay me a ceremonial visit.” Freud was granted the status of Bürger der Stadt Wien (honorary citizen of the city of Vienna) on the occasion of his birthday. His friend Josef Friedjung, in his dual capacity as member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society and socialist district councillor specializing in child welfare, joined Julius Tandler, Karl Richter, and the mayor in the ceremony. Aside from a formal commendation on “the excellence of his contribution to medical science,” the politicians praised Freud’s humanitarian efforts and his ability to steer foreign benefactors toward Vienna’s social causes, especially those of indigent children. For once the reward was the result of authentic idealism. “The honor proceeds from the Social Democratic Party,” he wrote to his son Oliver, much as he had to Abraham, but added in this letter that “the Worker’s Newspaper is celebrating me in a nice little article.”5 Actually the article in the Arbeiter-Zeitung was even more flattering. “A special obligation and gratitude falls to us Socialists,” the Social Democratic newspaper wrote, “for the new roads which he opened for the education of the children and the masses.”6 True, Freud was morosely preoccupied with the idea that this sixty-eighth birthday would be his last, and the recent accolades struck a recurring note—perhaps, he wrote, the city government hastened the tribute knowing that this birthday would be the final one. Regardless, he enjoyed his relationship with Red Vienna’s social welfare administration. More to the point, during the last six years Otto Bauer had overseen a remaking of the city and Freud was honored for his contribution to its new educational and psychological systems. By 1930, when the same medallion would be awarded to Alfred Adler, whose individual psychology was supported by Social Democratic Party officials like Carl Furtmueller, the role of psychoanalysis had expanded even further into the community.

Psychoanalysis had become so popular in Vienna that the Rathaus politicians turned over a city-owned building site at the lower end of the Berggasse, the street on which Freud lived, to house further psychoanalytic endeavors. The new building at Number 7, near both the medical school and urban transportation, would bring together the society, the Ambulatorium, and the Training Institute under one roof. But the building came without accompanying construction funds, and the plans for a centralized psychoanalytic establishment were set aside at least until 1936. In the meantime the thorny issue of lay analysis recurred again and again. Julius Wagner-Jauregg had reconvened the conservative Society of Physicians to examine the credentials of Theodor Reik, then practicing on the strength of his academic scholarship and psychoanalytic training with Freud. The challenge would draw Freud into the political fray the next year and prompted him to write The Question of Lay Analysis in 1927. But, more generally, as the programs of Red Vienna prospered over the next eight years, then leveling off, the psychoanalysts carried on the multiple clinical and educational functions of the Ambulatorium with surprising equanimity concerning the political situation.

Wilhelm Reich, now assistant director of the Ambulatorium, found his work with clinic patients to be mutually rewarding. The clinic allowed Reich to further his social interests by treating the emotional problems of poor and disenfranchised groups like laborers, farmers, students, and others with wages too low to afford private treatment. As an analyst he brought to the Ambulatorium a character well-versed in politics. “Material poverty and lack of opportunities,” he believed, exacerbated the emotional suffering and neurotic symptoms of poor people.7 Because sexual disturbances, the rearing of children, and family problems were inseparable from the larger context of social and economic oppression, Reich would eventually broaden the scope of psychoanalysis and add free sex counseling clinics to the outreach efforts already underway.8 While at the Ambulatorium, though, Reich deliberately sought to treat difficult patients who had been diagnosed as “psychopaths,” but were regarded as morally bad rather than “sick.” Frequently antisocial, they showed tendencies to be destructive (of self and other) in the form of criminality, addictions, rageful outbursts, or suicide attempts. Psychoanalysis, Reich believed, would free them of rage and allow a more socially productive motivation, or energy, to emerge naturally.

Only twenty-two years old and barely graduated from medical school, the impassioned Wilhelm Reich assumed the position of first assistant chief to Eduard Hitschmann at the Ambulatorium in 1924. Over the next six years the two men, in many ways opposite in character, would work together as co-directors of the clinic. Reich seemed to be privileged with apparently limitless visits to Freud, who bemusedly noted Reich’s Steckenpferd (hobbyhorse), his obstinate conviction that neurosis, whether individual or social, is rooted in sexuality.9 But he was genuinely well regarded by the analysts and especially appreciated for his imaginative, charismatic chairmanship of the Technical Seminar. Reich held these meetings weekly initially at the Ambulatorium and, from 1925 until 1930 when he moved to Berlin, at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society’s Institute.10 Reich’s initial seminar papers, where he pursued his earliest theoretical sketches of a new therapy based on individual character structure, were surprising not only for their content but also for their structure. Psychoanalysis, he said, should be based on a careful examination of selected unconscious character traits, later called ego defenses, that impede an individual’s acceptance of their natural self in society. Else Pappenheim, more a friend of Annie Reich than of Wilhelm, remembered the later popularity of “his book on character analysis that we all read. It was part of the curriculum. And,” she commented, “he was very respected in Vienna at the time.”11 Reich called for a new approach to the analysis of individual character. In due course he devised the format of the in-depth individual case conference, a format that still endures as the standard method for systematically summarizing and discussing therapeutic issues in clinical settings. Though a mere twenty-seven pages of handwritten minutes of the seminar’s case reports have survived, the analysts’ lively exchanges and imaginative critiques make clear why these sessions were some of the most valuable activities of the society.12 The analysts met in the windowless conference room of the Ambulatorium and, in at least the discussions of January 9, February 6, March 5, May 7, and October 1, 1924, supported each other’s efforts to treat all those who requested clinical treatment—without regard to fee. When Reich entered the conference room after a full day in the clinic, his relative youth vanished. He spread an electrifying energy all his own; his deep-set eyes, wavy hair, and high forehead of the rebellious German intellectual barely tempered by the military mannerisms of a Prussian army official. Under his leadership the analysts developed not only path-breaking clinical protocols but also attended to the more mundane aspects of running a clinic. They formalized the staff, record-keeping, and statistical requirements of the clinic for both internal use and public scrutiny. As a branch society, the Viennese would send off these reports for publication and distribution by the IPA.

Reports from the IPA’s branch societies’ activities had shifted, as of 1920, from the Zeitschrift to the International Journal of Psychoanalysis (IJP). Local groups around the globe forwarded to the IJP’s editors the minutes of their scientific and administrative meetings. The most thorough reports came from Berlin where Eitingon and Fenichel’s combined administrative talents produced an enviable array of detailed statistical tables. Not wishing to come in second best but skeptical of the dehumanizing effect of such accounting, Reich suggested an alternative model for the Ambulatorium ‘s statistical overview. The reports from Vienna, he said, would not merely depict past and present work. Rather they would be narrative portraits interspersed with numbers, diagnostic descriptions, and case notes on discharged patients. Reich and Jokl would organize follow-up studies and summon former patients, recontacting them as necessary. Careful wording of treatment plans (for example, designating an analysand “symptom free” instead of “cured”) was a critical exercise in public relations, especially given the imperative for confidentiality and the Ambulatorium’s relationship to public social services. Prospective patients must feel welcomed and former patients who had interrupted or ended analysis prematurely (or who had been intended for fractionary analysis) should feel comfortable enough to resume treatment.

Reich’s beliefs were hardly unusual among psychoanalysts at the time. Nor was 18 Pelikangasse the only psychoanalytic outpatient clinic. What Hitschmann called “unauthorized competition” generally came from clinics formed by Freud’s current rivals and former adherents like Alfred Adler and Wilhelm Stekel, a pacifist who had left Freud’s circle even before the war. A case in point was the October 24 announcement published in a local Viennese newspaper, the Wiener Sonn- und Montags-Zeitung (the Vienna Sunday and Monday Times), just over the weather section. “The Society of Independent Analytical Physicians, under the leadership of Drs. Anton Mikreigler, Wilhelm Stekel and Fritz Wittels, opened an out-patient clinic to make possible the analytic treatment of the poor and needy. Come in regard to: sexual disturbances, nerves, epilepsy and spirit disorders. Open Tuesday-Friday, 6–7 in the afternoon, 8th District, Langegasse 72.”13 Faced with an apparent onslaught of new psychological practices in clinics around the city, some entrenched older members of the medical faculty at the Allgemeine Krankenhaus, over in Vienna’s fifth district, sought to retaliate. This time, unlike their earlier efforts to block the Ambulatorium on professional grounds, they focused on the “problem” caused by large numbers of foreign students at the university. “The old professors have not been changed by the war and [are] still dictators, not open to the new psychology,” Dr. Eversole wrote to Richard Pearce of the Rockefeller Foundation, “while great work and stimulation [are] being put [forth] by the younger faculty.”14 Apparently these “old professors” were overcharging foreigners, in part simply to cover the financial survival of their departments (Freud had done the same). But many did not understand the nature of medical progress and, by enforcing the rules of traditional practice, prevented new ideas from expanding into Austrian medicine. From the American Eversole’s point of view, the foundation should give young Austrian doctors overseas study fellowships. From the perspective of Grete Lehner Bibring, Reich’s friend from medical school just then finishing up her residency, the traditional psychiatry and neurology of Wagner-Jauregg’s clinic was still pedagogically worthwhile. Jauregg’s organic biological treatment approach was frequently useful as a supplement to psychoanalytic practice, Bibring found, but his academic conservatism was distressing. And Helene Deutsch (who had completed her wartime rotation there) warned that treating illiterate men and women this way resulted merely in their blind submission. Deutsch wanted to work with “the most hopeless patients, the ones who had locked up their entire emotional lives deep within them, unable either to give love or accept it.” She recalled how “they would lie there in their beds, motionless and mute, as if dead, until after a period of ‘observation’ they were judged unpromising for further research, given the ominous diagnosis ‘stupor,’ and sent on to an institution for incurables.” Her older, traditional—and all male—colleagues were convinced that she was wasting her time. But Deutsch persevered and “learned that one can penetrate the thickest wall of morbid narcissism if one is armed with a strong desire to help and a corresponding warmth.”15 The message was not lost on the Viennese press, and soon stories about human suffering and psychoanalytic help were appearing in the popular local journals.

Among the more daring of these periodicals, one of the most open to psychoanalysis was a Viennese news magazine called Bettauer’s Wochenschrift. In mid-1923 the Wochenschrift published a series of enthusiastic articles on the benefits of psychoanalysis available at the clinic. The journal’s “unsolicited publicity for psychoanalytic therapy,” Richard Sterba recalled, “brought an influx of patients to the ambulatorium.”16 Sterba may have actually understated the magazine’s impact since over 350 men and women applied in 1924 alone. Hugo Bettauer’s novels, plays, and periodicals like Er und Sie: Zeitschrift für Lebenskultur und Erotik (He and She: A Magazine for Lifestyle and Eroticism), the Wochenschrift (Weekly), and Bettauers Wochenschrift (Almanac), all of which popularized psychoanalysis, sent more people seeking help at the Ambulatorium than therapists had time for. These widely distributed journals discussed sexuality candidly, called for unrestricted sexual emancipation, and openly advised psychoanalytic psychotherapy for people with sexual difficulties. References to Havelock Ellis, Magnus Hirschfeld, Wilhelm Stekel, and of course Freud were written into Er und Sie’s leading articles. The reporters chose to comment on five central moral issues, the same issues Wilhelm Reich also picked: hypocrisy of the state, homosexual and abortion rights, a double standard for women, homelessness, and the distinction between natural and pornographic sexuality. In November 1924 the new question-and-answer column, “Probleme des Lebens” (Problems of Life) gave young people, women, and adolescents a chance to voice their familiar concerns. Soon words like drive, impulse, sublimation, unconscious, complex, and instinct appeared in the regular weekly column written by a Nervenärzt (psychiatrist), along with his direct recommendation to seek psychoanalytic help if the words matched their mood, and troubled readers flocked to the treatment center on Pelikangasse. These inexpensive twelve-to-sixteen page daily journals mixed currents of gossip, entertainment, and political satire with serious sex education columns, novellas, personal ads, and a clinical forum on both normal and “abnormal” behavior. “Lonesome: You are 29 years old, intelligent, educated, with a good job and you long for a companion who would share with you sorrow and joy…. This is no doubt a case which necessitates psychoanalytic treatment. Consult with the Psychoanalytic Ambulatorium, Vienna, Ninth District, 18 Pelikangasse, Office hours from 6 to 7pm.”17 The papers had seriously feminist side that condemned the oppression of women and rallied to their cause in tones firmly suggestive of Reich’s work. “Daily one can observe the grotesque spectacle, the parents who permit their daughter to work eight hours a day in an office but prevent her from living her own life. She has to earn money, work under men and care for herself.”18 Readers who went to the Ambulatorium for psychoanalytic treatment, while perhaps neither sophisticated or psychologically informed, were fortified by Bettauer’s advocacy, the postwar possibilities for a better personal and family life and, particularly among women and young people, a new sense of citizenship.

If the populist Hugo Bettauer lamented sexual hypocrisy and heralded psychoanalysis as liberation from social repression, the elitist writer Karl Kraus also lambasted bourgeois society’s repressive sexual laws but famously mocked psychoanalysis as “the mental illness of which it considers itself the cure.”19 His celebrated satirical magazine Die Fackel (The Torch) published Kraus’s own freewheeling criticism of the clichés and sensationalism of the general press yet, in a bald internal contradiction, advocated for gender equality, women’s liberation, and generally much the same social agenda as Bettauer. Psychoanalysis represented a dividing line. At issue was less the theory of psychoanalysis than the feasibility of actually effecting individual and social change. Bettauer, who freely referred his blue-collar readers to the Ambulatorium, saw psychoanalysis as a genuine service that would relieve depressive overburdened human beings of their individual suffering and, consequently, improve their entire family and social system. Kraus by his own admission despised the idea of individual change but failed to understand the democratizing effect of personal transformation on the larger social and economic universe. Thus he accused Freud of blaming victims for their own oppressed predicament whereas Bettauer praised Freud for just the opposite, for relieving the individual of self-blame. Their disagreement epitomized the pro- and anti-Freudian argument that rages still today. But whatever intellectual confrontations inflamed Vienna’s café society, in the 1920s the psychoanalysts believed in helping workers, students, maids and butlers, army officials and unemployed people cope with personal misery.

Some of the stories are incredibly sad. An anorexic sixteen-year old girl is in love. Her loss of appetite is total, and she is losing body weight so rapidly that her hair is drying up and falling out. Should the Ambulatorium arrange for individual analysis, or should she be treated along with her boyfriend? August Aichorn had been known to intervene actively in these situations with adolescents at his St. Andrä therapeutic group home. The severity of the young girl’s condition seemed to be an emergency, so Hitschmann agreed to see the two young people together, in keeping with Reich’s approach. But—one always must ask—is “couples counseling” really analysis? Another sixteen year old suffers from attacks of Wanderlust. Maybe he “longs to die in a far away, sunny landscape, the opposite of the narrow womb” or maybe he is running away from an abusive home. Are this adolescent’s exhibitionistic tendencies really signs of schizophrenia? Yes, because he had a systematic delusional body image even as a four year old. He had probably been discharged too soon and would have benefited from longer-term therapy at the Ambulatorium since classical analysis was, after all, possible after puberty. In this way patients’ cases were discussed for at least thirty minutes each, in clinical meetings held every other week at 8:30 at night in a basement room ostensibly stripped of its medical functionality but, in fact, still an emergency entrance for heart attacks.

Maybe he did resemble a white-haired German pastor with an abundant mustache, but Hitschmann could zero in on the comic and lighten up his most pretentious colleagues.20 He stopped an exhaustive discussion on erythrophobia and schizophrenia with a joke: “The analyst must ask with his dying breath: What comes to your mind about this?”21 Hitschmann’s banter, recorded in clinical minutes and long remembered by Helene Deutsch and other analysts, brought welcome relief to the group of intense and austerely disciplined physicians. He and Reich were surely put off by Federn’s cold use of the term differential diagnosis, a descriptive phrase borrowed from academic psychiatry to explore how a range of symptoms can cause one illness. But where Reich was combative, Hitschmann parodied the distant, scientific psychoanalyst more concerned with technique than relieving human misery.

Reich enjoyed these clinical debates immensely. Even in the 1920s some of Freud’s colleagues were tempted to practice psychoanalysis along the lines of an idealized and rigidly “orthodox” protocol. In actuality most analysts, especially Freud, exercised nearly all variations of clinical flexibility. The dispute over what constitutes an appropriate length of treatment reappeared in every clinic and in almost every series of clinical notes. In Berlin brief therapy was eventually regarded as an official curative technique called “fractionary” analysis. In Vienna the clinicians asked whether they “should endeavor to achieve quick successes in order to shorten the duration of the treatment.” Federn questioned the wisdom of discharging patients at their own request. But since after all nobody was ever symptom free, he agreed that interrupting the analysis could be a viable shortcut in treating the problem. Then again, lengthy treatment was just as debatable. To cite an instance, Reich accused Hoffer of retaining a thirteen-year-old patient in treatment too long because he felt like a beginner abruptly handed a difficult case. The boy was referred to the Ambulatorium for “educational problems,” but in truth he ridiculed and insulted Jews and was a member of an anti-Semitic section of the Boy Scouts whose leader called psychoanalysis “Jewish filth.” During the case conference Reich urged Hoffer to consult directly with Hitschmann, while Federn and Felix Deutsch dispassionately wondered if the youth was acting out an aggressive castration complex without knowing that the youth was circumcised. What emerges from this lengthy disputation on body image, sexual repression, and birth trauma among four men who are themselves Jews is an uncanny—perhaps naive—ability to detach from Vienna’s dangerous anti-Semitism and concentrate instead on curing a young boy with school problems. The detachment presupposed, naturally, faultless trust between colleagues and in the outpatient system they were creating.

The Ambulatorium’s reporting system required analysts, regardless of their status in the clinic hierarchy, to send Reich weekly written summaries. Oral reports, he thought, resulted in irrelevancies and disorganization. While the written reports were carefully collated by senior analysts, the oral reports, as the purview of less experienced trainees, were presented once every three months to the seminar and at least monthly to the supervisor. Anyhow, if distributing written reports placed patient confidentiality in question, the indiscrete character of the oral reports only added to the probability of turmoil. Accordingly a log was instituted to identify patients only by preassigned numbers. Interruptions of analysis, reduction or expansion in the number of sessions, and clinical difficulties were documented in writing. Signs of danger like suicidal or homicidal gestures, or ominous auditory or visual hallucinations, and major modifications in treatment were reported immediately. Such regulations were necessary because people with mental disturbances of every kind had found their way to the Ambulatorium. But with all of this ritualized supervision and accountability, what would happen to the spontaneous exchange of clinical ideas, the satisfying core of collegial exchanges? To safeguard the scientific nature of the seminar, a period for debating questions of technique was formally set aside for the end of every case presentation. Without these discussions, the Ambulatorium might have found itself too bureaucratic, just another one of Tandler’s social welfare agencies.

Nobody knows now how many kinds of fringe and underground political people were treated at the Ambulatorium, but the analysts had to guard against lapses in confidentiality at all times. Even as danger closed in on the clinic in the early 1930s, analysts maintained this rule. Confidentiality meant that a patient’s politics were protected from the couch to the conference room. Of course this level of trust was possible because analysand and analyst largely shared the same left-wing convictions. Most believed, Helene Deutsch later said, that social change was inevitable and “socialism was not a label [but] … a perfectly respectable thing to be.”22 Exit pass forgers, industrial spies from Russia, perhaps even incipient Nazis were in treatment, and so, for Grete Bibring or Richard Sterba, a patient’s desire to join a political party posed no conflict with her ongoing psychoanalysis.23 Sterba had exchanged his hospital job for a similar position as the Ambulatorium’s resident psychiatrist. The new job entailed a loss of income but Wilhelm Reich broached the possibility of private patient fees to compensate for the pay cut. This proved to be difficult. As in-house psychiatrist, Sterba conducted five analyses of Ambulatorium patients each week. Still, he relished the opportunity and dispensed with luxuries in the thrill of adhering to his chosen vocation. Under the harsh lights of the Herzstation’s examination rooms, Sterba was free to adopt a personality unique to mental health professionals—father and son, consoler and conscience, guardian of sexual secrets and protector of the intelligence of dreams.

Typically for Hitschmann, the stress placed on the Ambulatorium by his relationship with the state overshadowed his feeling of accomplishment. On the one hand, he was pleased that “our collaboration has always been most harmonious and the spirit of humanity and conscientiousness in dealing with our poor patients has at all times been eminently upheld.” On the other, he chafed at the perception that the Ambulatorium was being held to different—and possibly more burdensome—sets of regulatory standards and civic demands than the Berlin Poliklinik. It was different from other municipal clinics in that it accepted only private funds while treatment referrals kept coming from government agencies.24 The Viennese analysts had to cope with myriad referrals received from the municipal welfare authorities, the courts, Wagner-Jauregg’s psychiatric clinic, health insurance societies, and the Matrimonial Advisory Center. “Here in Vienna,” Hitschmann reported, “we were under the most rigid necessity of accepting only such patients as were demonstrably without means, so that for many years they contributed nothing whatever financially to our expenses.”

Because the “salaries of the medical staff and fees of part-time physicians made very heavy demands … over and above the expenses of maintenance,” as Hitschmann reported, fund-raising could no longer be left to spontaneous but inconsistent donations. In discussions of clinic administration at organizational meetings like the one held on May 7, 1924, Hitschmann, Helene Deutsch, Otto Isakower, and Dorian Feigenbaum agreed that the Ambulatorium’s financial affairs had to be purposefully systematized. A 4 percent charge, they decided, would be levied on every member of the society to help defray the costs of the Ambulatorium, just as the Berliners had done for their own clinic.25 This increased the Ambulatorium’s cash on hand so that salaries could be paid, furniture rented, and publications issued. By 1924 the funding strategy, along with other occasional infusions of cash from enthusiastic analysts, had stabilized the Ambulatorium’s fiscal situation and finally allowed for the financing of salaried positions. Members of the society who decided not to treat patients free of charge found themselves, according to the “one-fifth” rule, contributing to the salaries of a growing number of assistants and interns at the Ambulatorium. Reich even took to soliciting small monthly payments from nonindigent patients who could contribute to the clinic’s administrative expenses. Many years later Wilhelm Reich recalled how his vigorous efforts to collect the 4 percent dues from his fellow analysts provoked Freud’s expressions of pleasure in the early 1920s.

Obviously the Ambulatorium was no more immune to internal politics than to external ones. During the Eighth International Psychoanalytic Congress held in Salzburg that April, Siegfried Bernfeld asked Ferenczi to consider moving from Budapest to Vienna and take over the clinic since Hitschmann was so disliked by his society peers. Hitschmann, he said, lacked personal initiative and the capacity to motivate younger analysts. Freud rallied to the invitation, lavishing Ferenczi with his “complete sympathy and highest interest” for the transfer and tempting him with elaborate incentives. “If I were omnipotent,” wrote Freud, “I would move you without further ado.” He offered to assign Ferenczi all his foreign patients, appoint him to replace Otto Rank as his successor, and even find him living quarters.26 But both Freud and Bernfeld had to admit that the reach of Hitschmann’s engagement with the Ambulatorium ran deep. Charges of inefficiency were barely credible since he was, at that moment, negotiating with the wife of a wealthy retired banker to invest in a new building for the clinic complete with an apartment for the resident director. Freud subsequently met with Frau Kraus that July and at several intervals throughout the year to iron out the details of the intended clinic, including its future director. But the building project never actually worked out. “The prospect of getting a house for an out-patient clinic,” Freud wrote to Abraham, “has evaporated. The wealthy lady who wished to build it is now acting as if she were offended and is withdrawing.”27 Despite multiple incentives, the honor of being chosen and his personal devotion to the cause, Ferenczi finally decided to forego the Vienna offer because an even greater challenge—America—lay ahead.

For Sándor Ferenczi, the idea of founding a psychoanalytic outpatient clinic in America, “for which money is supposedly available … for two to three years,” was irresistible.28 In addition to a growing number of professional invitations for lecture series and consultations, this particular proposal came from Caroline Newton, a controversial figure on both sides of the Atlantic. Ferenczi neither accepted nor refused, first telling Freud about the offer as, in fact, Newton had requested.29 In New York Newton was then at the epicenter of the escalating international dispute over the requirement for an accredited medical degree in order to participate legitimately in the psychoanalytic movement. The argument over lay analysis reflected in microcosm the differences between Americans and European psychoanalysts who, while less overtly murderous than the Montagues and Capulets, held equally intransigent views of each other. For Freud and the Europeans, psychoanalysis was above all a humanist endeavor best practiced by well-analyzed trainees regardless of their academic credentials. For Abraham Brill, as titular head of the American movement, psychoanalysis was a medical science to be guarded against intruders by physicians accredited by the American Medical Association. Thus when Caroline Newton, a social worker first analyzed by Freud in 1921 and more recently by Rank, attempted to open a practice in New York, the New York Psychoanalytic Association responded with outrage, and ejected her from their meetings for violating their privileged medical boundaries.30 The resulting uproar prompted Brill to promote even more restrictive membership clauses and Newton, already a member of the Viennese society, to attempt a free clinic like the Ambulatorium in New York. Nothing could be more un-American than the combination of social work, lay analysis, European training, and provision to poor people of the kind of mental health treatment hitherto reserved for the affluent. The clinic project failed, but Ferenczi pursued his plans to visit America, only intensifying Freud’s penchant for outrageous comments. “It is an extremely unfree society, which really knows only the hunt for the dollar,” he wrote in 1921, calling the United States “Dollaria” and defying the Americans to start the kind of clinics seen in Weimar Berlin or Red Vienna.31

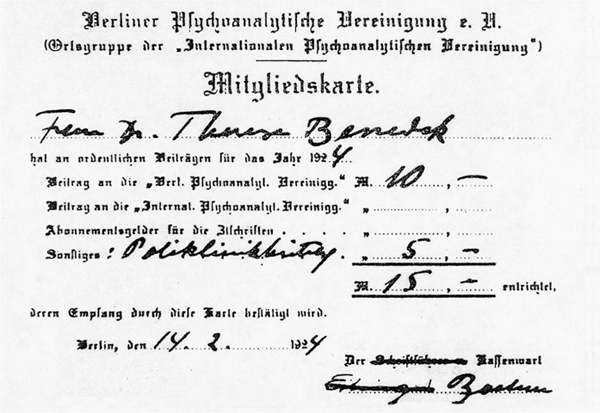

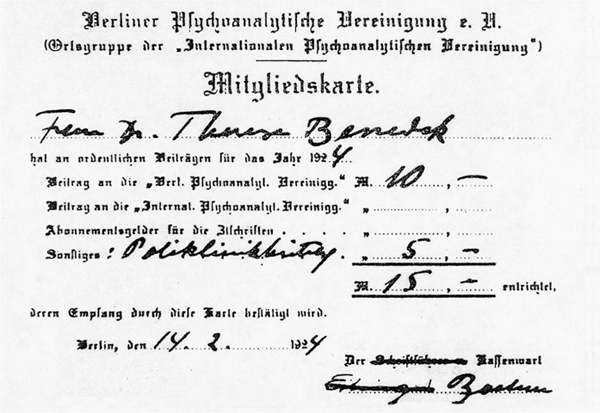

In Berlin, in fact, the Poliklinik’s attention to the patient was different. Josephine Dellisch, a Poliklinik patient, was an unemployed schoolteacher who, like many, was ambivalent about her analysis. Did she truly lack the money to pay or was her financial distress a form of resistance against pursuing analysis? Her reasons were “mere pretexts—exhausted by the term—school moving to a crisis, no money to live in Berlin & no friends to help her—can’t face taking a temporary post as governess, or giving lessons” wrote Alix Strachey to James, Freud’s future English translator, in her letters from Berlin. Eitingon simply would not permit finances to come between her and treatment. He “twice said very impressively that the money ‘was there,’ only the question was how to press it into that lunatic’s hand.”32 In other words, Eitingon believed that people like Dellisch had a right to treatment, regardless of their ability to pay. He, like Freud and other Social Democrats, had come to believe that payment and nonpayment alike were clinical issues and were more significant for the therapist than for the patient; eliminating the fee altogether could free analysands to explore and resolve impediments in their work and personal lives. Of course, in order to maintain this level of neutrality, the need to raise funds toward the Poliklinik’s upkeep was unending. First the administrative committee checked to see how the Viennese balanced rental expenses, staff salaries, and patient subsidies. Next they decided to look for outside donations though society members’ voluntary subscriptions and dues would continue in 1924, as in 1923.33 New members saw this most starkly. Therese Benedek’s renewed Mitgliedskarte (membership card; figure 22) in the 1924 Berlin Psychoanalytic Society identifies her dues quite specifically. In addition to the ten-mark fee collected for membership in the society, the secretary hand-entered a five-mark fee levied strictly for the Poliklinik. Predictably, the five marks scarcely compensated for the fees not paid by the clinic’s patients.

Dellisch’s financial and psychological predicament as an unemployed teacher was increasingly common in Germany of the mid-1920s. Like the distressed segments of Austria’s middle class, Germany’s impoverished university professors attracted the philanthropic attention of the Rockefeller Foundation. But after Raymond Fosdick of the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial commissioned a confidential study of the country’s “intellectual workers,” the situation was found to be less dire in Austria. Approximately two hundred medical scientists were already receiving relief in the form of stipends, scientific literature, experimental animals, and laboratory supplies. Otherwise, “I find no critical situation demanding immediate action,” Guy Stanton Ford reported from Berlin.34 Berlin’s affluence relative to Vienna’s was noted by another Rockefeller deputee, H. O. Eversole, who reported that young men “had work in Germany but no sufficient material or clothing to go. It is an odd feeling on my part to assist young technicians to go to Germany,” Eversole wrote to Richard Pearce in the New York office, “where they have work awaiting them, when we consider all of the propaganda about alleged unemployment and hardship in Germany!”35 Indeed the sheer number of libraries, academies, and special institutes was so large that at least one institution was likely to have the necessary books and periodicals. Salaries were low, but so were costs, and the standard of living of the “intellectual professions” seemed, for the moment at least, relatively stable.

22 Theresa Benedek’s membership card in the Berlin Psychoanalytic Society, with its additional fee for the Poliklinik (Thomas Benedek)

For Berliners in early 1924, the practice of psychoanalysis was still avant-garde, a bit more culturally sophisticated and perhaps less clandestine than in Vienna. When “old friend Fenichel turned up,” Alix Strachey wrote, he had already “migrated for a year or two from Vienna to get a little extra polish on his brain. A good idea.”36 And Helene Deutsch wrote to her husband Felix, that in Berlin “there is no mood of panic, no barricades, no starvation,” despite the imminent elections and some of the harsher aspects of daily life like inflation and the landlord’s perpetual threats of eviction in favor of Americans.37 Alix, always the caustic but astute observer, in essence agreed with Helene about Berlin’s atmosphere. “Most people seem apathetic” about the parade of trucks draped in German nationalist black-white-red flags and young patriots, she wrote to James from her favorite table at the Romanisches Café.38 The Poliklinik analysts’ festive social life unfolded in these cafés and in the concert halls, in weekend visits to the countryside, at the movies and cabaret shows, and in each other’s apartments. Fenichel, Bornstein, and Wilhelm and Annie Reich liked to picnic in the woods by the Marditzer Lake and discuss what they were doing in psychoanalysis while Fenichel, who brought along his portable typewriter, remained ensconced in his manuscripts. Along with Radó and Alexander, they gathered at Melanie Klein’s or the Abrahams for long soirees. The Eitingons held tea parties, hosted a literary salon, and had a hand in social gatherings of cultural émigrés from the Russian diaspora of the 1920s.39 Alix, herself no stranger to refinement, was enthralled by Max and Mirra Eitingon’s mid-Victorian house in the Grünewald. “I suspect the man of having taste,” she wrote to James. “Or perhaps his wife. It was heavenly to lean back and look at rows & rows of bookshelves, & well-arranged furniture and thick carpets.“40 On a warm weekend in October Simmel led a travel party to Würzburg to see the Tiepolo trompe l’oeil frescoes in the Bishop’s Palace and to drink Main wine at a choice local Ratskeller. Hans Lampl, Radó, Alexander, Jan van Emden, Josine Müller, and Hanns Sachs explored the lovely hill town of old houses and a rambling river. The same friends enjoyed Berlin’s weekly succession of dances and balls, the Feuerreiter Dance, the Kunst Akademie Dance, and an occasional underground costumed ball—Simmel once dressed up as a Berlin nightwatchman—in the winter. Melanie Klein loved the balls and always wore wonderful hats. The famous golden decadence of Berlin in the 1920s, the sultry cabarets, the transvestite dance floors, the bars and amusement parks, surrounded the psychoanalysts and easily drew them in. “There is no city in the world so restless as Berlin,” wrote the British diplomat and biographer Harold Nicolson. Married to Vita Sackville-West of London’s Bloomsbury group, Nicolson was no stranger to either psychoanalysis or its encroachment on Berlin’s avant-garde society. “At 3 A.M. the people of Berlin will light another cigar and embark afresh and refreshed upon discussions regarding Proust or Rilke, or the new penal code, or whether shyness comes from narcissism.”41

Dedicated bon vivants, Sándor Radó and Franz Alexander joined these smoky arguments on occasion, but other Poliklinik analysts like Ernst Simmel seemed to relish discussing theory day or night. Simmel was especially attracted to left-wing political circles. At the institute he immediately joined up when Otto Fenichel called the first meeting of the Children’s Seminar. Virtually identical in style and structure to the sexology seminar in Vienna, this was a semiformal study group that met every few weeks in private homes to explore topics outside the institutional curriculum. Fenichel soon pushed his case for a serious political focus and his friends, who would join him ten years later in a last-ditch effort to uphold Marxism in psychoanalysis, seemed to agree. Erich Fromm, Annie and Wilhelm Reich, Edith Jacobson, Francis Deri, Bertha Bornstein, Kate Friedländer, Alexander Mette, Barbara Lantos, and others gathered 168 times in groups of 5 to 25, from November 1924 until at least 1933.42

By 1924 Simmel had become increasingly interested in the interdisciplinary efforts of a highly original group of intellectuals, known since about 1930 as the Frankfurt School, who had opened their own academy in 1923 to explore social and psychological theory with uncompromising depth. The most philosophical members (Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse) and the cultural critic Walter Benjamin would not affiliate with the researchers for at least five more years. But the psychoanalysts, led by Simmel, were already intrigued by the Frankfurt School’s academic debates, which often paralleled their own theoretical approaches. Erich Fromm would join the school along with Karl Landauer, founder of the co-resident Frankfurt Psychoanalytic Institute in 1929. By then Landauer had already formed the Frankfurt Psychoanalytic Study Group with Fromm and his wife Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, Heinrich Meng, and Clara Happel. As the analysts diagnosed individual pathology, so the social scientists diagnosed the larger pathologies of Western society. Where the analysts probed interpretively into an individual’s unconscious world, the Frankfurt School analyzed sociopolitical motivation and eventually emerged with Critical Theory, their own Marxist dialectical methodology. Most clearly articulated in the early 1930s by Max Horkheimer, Critical Theory analyzed facets of industrial culture and society, with a specific cultural emphasis on the reciprocity between political and economic factors. With their affiliated psychoanalysts critiquing Freud and their philosophers critiquing Marx, both from the left, the Frankfurt group did attempt a theoretical integration of the two perennially irreconcilable conceptions of the human world. This optimistic synthesis was one of the Frankfurt School’s boldest attempts to break through traditional academic wariness and intellectual clichés. Eventually the Ministry of Education authorized the construction of a future home for the Institute for Social Research at 17 Victoria Allee in Frankfurt. It was a stark five-story stone building with small windows and few adornments, architecturally sedate but famous for housing Erich Fromm and the Frankfurt Psychoanalytic Institute. Until it was forcibly expelled by the Nazis, the Frankfurt School investigated the most nettlesome problems of the era, beyond the platitudes of party affiliation, and promoted a critically rigorous dialogue between psychoanalysis and Marxist theory.

Given the earlier opposition in Vienna to an official training program anything like that of the Berlin society’s, let alone the Frankfurt School, Helene Deutsch was surprised to find a new regard for psychoanalytic courses when she returned after her year in Berlin. Deutsch was pleased and rallied her Viennese colleagues around the idea of attaching their training program to the Ambulatorium. “I turned out to be a good organizer,” she recalled from her youthful community work with women.43 At the same time, John Rickman convened members of the British society to review their own plans for a clinic and a training program in London. Whereas little came of the discussion there (London’s clinic project was progressing, though slowly), in Vienna Deutsch aimed for an opening in the fall term of 1924. She envisioned a joint institute and clinic where the Technical Seminar would bridge the needs of students in the psychoanalytic training program and the senior analysts would teach more advanced courses. Deutsch prevailed and the Training Institute was started that October with only one major change from the Berlin system—in Vienna the clinic and the Institute were legally separate. Strategically, what appeared to be a concession to the local medical organizations and government authorities was actually a triumph: it allowed the analysts to train, for example, educators who had been excluded from the clinic by the government’s insistence on medical-only personnel. The Institute was quickly swamped with applicants. Some came from Germany to escape the “rigid discipline” of Berlin, only to recoil because they had underestimated the new program in Vienna.44 Four candidates were selected for full training and soon joined the eight students who had completed their personal analyses and begun clinical work supervised by Hitschmann at the Ambulatorium.