“Although absent from the opening of the Clinic, I am all with you”

THROUGHOUT the early years of the free clinics, psychoanalysts in various countries followed a well-organized sequence, a “logical order,” Ernest Jones would say, of first constituting a local society amongst themselves, next issuing a clinical journal, and finally organizing a training institute. After 1920 a fourth component was added, the outpatient clinic. The Berlin and Vienna societies had theirs and now so too would the British. “The chief news from London is good,” Jones had told Freud just before Christmas of 1925, “an old patient of mine has given two thousand pounds to … start a clinic early in the New Year.”1 Jones had reason to be excited. This tremendous financial donation from Pryns Hopkins, an American industrialist named by the British society’s as their own “Honorary Almoner,” allowed the analysts to open their new clinic “for the purpose of rendering psycho-analytical treatment available for ambulatory patients of the poorer classes.”2 Freud was delighted. Not wasting any opportunity to bash the United States, he complimented Jones on his “good news…. I have always said that America is useful for nothing but giving money. Now it has at least fulfilled this function…. I am happy that it happened for London…. My best wishes for the thriving of your institute!”3 Eitingon too sent a telegram with congratulations from the Berlin society.

The London Clinic of Psychoanalysis was officially inaugurated on Freud’s seventieth birthday, May 6, 1926. At eight o’clock in the morning John Rickman welcomed the first patient to the newly leased premises at 36 Gloucester Place in the center of the city, London West 1 (figure 24). Other patients were delayed, however, until the following fall. At first the analysts occupied only a portion of the Gloucester Place townhouse and sublet the upper two floors. Building construction frustrated their attempts to develop a daily clinical schedule, and finally they admitted that necessary renovations would postpone their prospects for a fully functioning clinic until September. In spite of that Jones grew increasingly eager as opening day approached and dashed off note after note, barely containing his excitement in anticipation of Tuesday, September 24. Over their twenty years of fellowship Freud, who claimed to detest ceremonies, had come to realize how much Jones loved them and greeted his triumph with impeccable courtesy. “Although absent from the opening of the Clinic tomorrow, I am all with you and feel the importance of the day,” Freud wrote to his friend.4 The British society then formally delegated responsibility for the clinic to a board of managers. Ernest Jones greeted well-wishers as director of both the clinic and the Institute, while Edward Glover assumed the position of assistant director, and Drs. Douglas Bryan, Estelle Cole, David Eder, William Inman, John Rickman, Robert M. Rigall, and William Stoddart made up the remaining staff. Sylvia Payne and Marjorie Brierley, the only two women on the senior staff, interrupted their professional work to assume “domestic” responsibilities and oversee the care of the building, supervise the maintenance and cleaning crew, and allocate the treatments rooms. And finally Warburton Brown, Marjorie Franklin, Lionel Penrose, and Adrian Stephen were appointed as clinical assistants allowed to conduct psychoanalysis under supervision. Jones was particularly pleased that he and Glover had arranged the control of analyses because the clinic would now be legitimately linked to the Institute.5

24 The London Clinic for Psychoanalysis on Gloucester Place (Photo by Claudine Rausch)

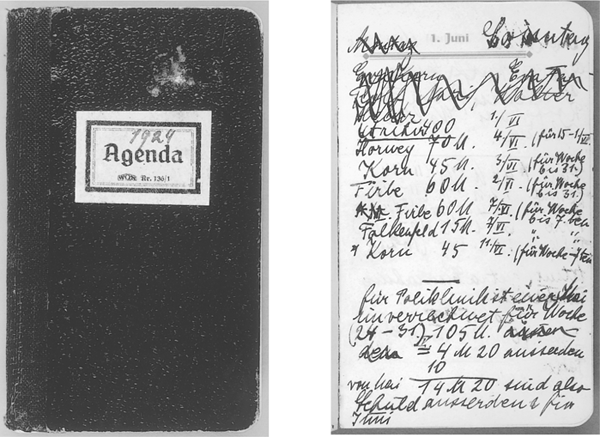

Later in November, in the last year of her quest for a permanent home for herself and her ideas, Melanie Klein arrived in London. Her relocation from Berlin could not have been better timed. The London clinic was just starting up and Klein was ideally prepared to contribute to its success. In some ways her decision to accept Jones’s invitation to join the British society was tinged with regret, and she added a little goading as well. “Simmel is said to have made a positive pronouncement on my work and its prospects for the future,” she wrote in her acceptance letter, “and to have expressed the hope that I will return with new stimuli from London to Berlin.”6 Instead she took to the London atmosphere well and stayed there, as always controversial, until the end of her life. After more than six years of strife surrounding her analysis of children in Berlin, Klein could now clarify her “ideas connected with education” and base them on “notes from the analysis of a child aged five years” with far less fear of her colleague’s ill will.7. Melanie Klein was a diligent note keeper and attentive to the minutest details of her small patients’ words and drawings. Her London work with “Alan,” “Julia,” “George,” and “Richard” formed the core of A Narrative of Child Analysis. Like her democratic colleagues in Berlin and Vienna, Klein treated at least one patient at no charge daily or performed an equivalent service to the clinic. She kept notes of these appointments in tiny jewel-like pocket diaries, the identical size every year from 1923 until 1946, with maroon leather covers so worn they seem black, indistinguishable from each other except for the year stamped in gold. Many of her patients were children for whose play therapy she ordered painted wooden toys from a special supplier in Germany. The children’s fees were noted, in Klein’s own abbreviated German mixed at times with a touch of Hungarian, with particular reference to the accounts she maintained (until 1926) for the Poliklinik. “I am obligated to the Polik. for 26 marks, 6 k. for September,” she scrawled on October 31, 1924.8 She wrote in black ink with a classic fountain pen, but her penmanship was erratic and often sloppy. Some days she tracked her accounts in hours of service due to the clinic. “For the week [of May] 24–31,” she noted on June 3, “I am responsible for 14 hours, 20” (figure 25). The same system of clinic duty applied now that Klein was in London. She also recognized that, as at her other clinics, candidates who could not afford to pay for their didactic analysis were seen as “clinic patients” by training faculty in lieu of the now customary outpatient responsibility. All told, the clinic staff treated about twenty-five patients daily. As at the other clinics, men and women of all ages and occupations lined up for the initial consultations. Arriving there on the advice of physicians or family, the prospective patients waited for intake interviews held alternately by Jones and Glover one day each week, Tuesdays at 5:30 P.M. An astounding one hundred such consultations were volunteered in the clinic’s first nine months and, equally surprising, almost all the examinees became full analytic cases, with many staying on past the initial six months of treatment. The London clinic never broadcast its services to the public and never even advertised in local newspapers for its first ten years, but still the requests so far exceeded the staff’s capacity that their waiting list reached back a full two years.

To avert a potentially overwhelming demand, the London analysts drew up a design for a waiting list before the first year was out. Treatment at the clinic was free of cost from the start and remains so even today. The waiting list was divided into three rubrics: urgent cases, cases particularly well suited to students, and the perennial remaining cases. Since the entire enterprise revolved around the intake procedure, Jones and Glover were soon compelled to establish three more categories of patients not placed on the waiting list. An intake interviewer’s purview is very broad, listening as impartially to the neurotic complainers as to the florid psychotics but mostly to generally well-balanced people overwhelmed by a wide variety of daily crises. Thus the first of the new categories, “on the spot advice,” classified mostly parents and children with sudden school crises; arrests for petty crimes with an obvious psychological overlay like kleptomania, or perhaps domestic violence. The second category, “consultation with the patient’s regular doctor;” was for complaints of ambulatory headache, asthma, epilepsy, narcolepsy, digestive disorders, and other occasional inquiries about somnambulism and tics. Finally the third group of patients, those whose presenting problems would be better helped at another medical facility, came with heart disease, drug addiction, and severe schizophrenia. The staff, who met quarterly, were satisfied with the therapeutic results and modestly estimated that some patients had been cured and several others “greatly benefited.”9

25 Melanie Klein’s agenda from 1924 and a page of entries showing her earnings, patient hours, and Poliklinik dues (Wellcome Library, London)

In Vienna Grete Lehner Bibring and Eduard Kronold had teamed up with Reich and Hitschmann, the four together now constituting the professional staff of the analytic clinic in full force. Richard Sterba joined them officially after presenting his initiation paper “On Latent Negative Transference,” which Reich found very impressive, to a Wednesday evening society meeting. This paper granted Sterba full membership in the society, but his admittance also gave the Ambulatorium an outstandingly loyal practitioner who would preserve the clinic’s integrity until its unsolicited demise in 1938. Still, the team was more immediately concerned with the need to screen every prospective child, adolescent, and adult patient at intake and to engage them as soon as possible in psychoanalytic treatment. The highest numbers of children treated in the Ambulatorium’s history were screened in 1926 and 1927. Even children under age ten (and elderly people ages sixty-one to seventy) were seen and counted, though they represented only a small fraction of the Ambulatorium’s total patient population. As usual more males were treated than females, with about seven boys and five girls regularly accounted for. Little in their clinical experience had prepared the analysts to take on child cases, the “little patients from the ghetto,” as the American Helen Ross said, and most of the analysts except for Hermine Hug-Helmuth and Anna Freud were novices.10 One day Jenny Waelder-Hall, a pediatrician at the Kaiser Franz-Josef Hospital for five and a half years and already analyzing adults at the Herzstation, there took on her first child case, a young boy initially interviewed by Anna Freud. Fortunately the hospital was nearby, so while her medical responsibilities did not accommodate the clinic’s odd afternoon hours, Waelder-Hall still opted to start her case the very next day. Anton, a shy nine-year-old school boy, experienced such profound night terrors that his school performance was affected badly and eventually al his family’s routines were interrupted. Recurring images of violent beating scenes between his parents intruded into his sleep. He was haunted by the agonizing mental picture of a foiled attempt to rescue his mother at age three, thwarted when suddenly he fell—he was told later—badly injured, and the whole family landed at the police station.11 Banned from games with his little playmates, Anton developed a lively fantasy life of invisible daytime friends and nighttime enemies. The delicate clinical dilemma posed by this case—how to relieve a child of exactly those unconscious fantasies that permitted his conscious daytime survival—impressed upon the child analysts the need for clinical oversight and guidance.

The concept of a seminar in psychoanalytic technique, by now Reich and Bibring’s standard method for discussing adult patients, was easily transferred to child analysis. Since Anna Freud was the natural choice to lead the new weekly supervisory seminar, Monday evenings were assigned and Edith Buxbaum, Editha Sterba, August Aichorn, Grete Lehner Bibring, Marianne Rie Kris, Annie Reich, Anny Angel-Katan, Dorothy Burlingham, and Willi Hoffer joined the project, “On the Technique of Child Analysis.” “So many people heard about our seminar and started to come that the meetings were full,” Jenny Waelder-Hall recalled, “Kris, Waelder, everybody who was somebody and even nobody, came.”12 For Dorothy Burlingham, the seminar was one of her first official introductions to the life of Vienna’s psychoanalysts. Anna Freud’s future life companion Dorothy was the sad, rich daughter of Louis Comfort Tiffany and had recently brought her four children to Vienna. As her interest in psychoanalysis grew beyond the need for personal relief, she started to attend the seminar. Most meetings were still held at the Ambulatorium, she remembered, in the “smoke-filled lecture room of the Herzstation in the University District … a center for heart research during the day and psychoanalytic headquarters come evening.”13 But space at these “headquarters” had become so crowded by 1926 that the hospital administrators threatened, once again, to evict the clinic. In due time the Ambulatorium and the Institute were allowed to stay while the society meetings moved a few blocks away. Anna held her own seminars in a separate set of rooms on the Berggasse. The courtyard window of her waiting room was straight across from her father’s, but Freud never joined the group because, as Jenny Waelder-Hall said, “he knew if he were present, none of us would function.”14 Challenged by the accelerating numbers of child patients referred by school teachers and beholden to the Ambulatorium’s mission, the original seminar grew with wildfire speed and had to be reorganized into three separate, more manageable courses. The range of cases heard in the technical seminar on child analysis reflected the census of Vienna’s working families, from Annie Reich’s case of a runaway child prostitute to Dorothy Burlingham’s attempt to involve an unschooled mother, a janitor, in the sex education of her eight-year-old daughter. Outside their common concern for the public good, very little had prepared the analysts for the class issues welling up in their work at the clinic. The eight-year-old girl was a perfect example of their naïveté. When Dorothy advised the mother to discuss sex with her daughter and explain “why it is useful and not dangerous,” Waelder-Hall recalled from the case conference, the janitor let loose. Nasty pictures might be fine for the fancy analyst’s children, she railed, but she cleaned a house full of bachelors, and who knows what her little girl would do! The small patient fled the Ambulatorium and just as fast the analysts realized that they had to acquire a whole range of new skills for working with families, school teachers, guidance counselors, and social workers. Small wonder that Adler’s desexualized child counseling was meeting with such success among the Social Democrats. Adler’s course on psychoanalytic pedagogy flourished precisely because it abated the prevailing discomfort (then as now) with the ideas of childhood sexuality, aggression, and fantasy among teachers of young children. Childhood aggression was viewed less critically by August Aichorn, also a member of the seminar, and his empathic responses to troubled children made him a vivid teacher. Aichorn led a seminar subsection on adolescence and delinquency, and ran it from his own little clinic in the basement at 18 Pelikangasse.

Because they were so poor, indigent and working-class adolescents were usually the last patients seen by municipal guidance counselors even though, as Aichorn and Reich knew well, their distress signaled more than just a troubled stop on the way to adulthood. Even capable parents became abstracted when their teenagers talked about the inevitable anguish of growing up, a personal torment that seemed to engulf all of family life in suffering. Aichorn and Adler, in contrast, were fascinated by adolescent depression and, now that their therapeutic approaches were better known, other therapists started building on their methods. As it happened, Professor Schroeder of Leipzig University’s neurology institute decided to open an adolescent clinic in November. To start the new polyclinic and observation center for young criminal offenders, Schroeder first convinced hospital officials to set aside one large room, for visitors, and several smaller treatment rooms. His next addition was a Sunday afternoon lecture series, where local psychiatrists gave talks about their work at the adjoining observation center. Of course there were other facilities near Leipzig for girls and boys, but none provided treatment for trauma or complex oedipal situations. Schroeder’s clinic was grounded in the methods Aichorn had published one year earlier, in Wayward Youth, and on Bernfeld’s reports from the Kinderheim Baumgarten.15 The Leipzig therapists identified with psychoanalysis and many were, in all likelihood, candidates in training at the Berlin Poliklinik. When Teresa Benedek, who moved easily between Berlin and Leipzig, took over direction of the local study group in October, she hoped that the sociologically oriented psychoanalyst Erich Fromm and Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, both of Heidelberg, would join either her group or the newly formed Frankfurt subsection of the Berlin society. Even the press was aware of activity within the psychoanalytic movement. At the top of the Leipziger Volkszeitung’s edition of October 13, 1926, an editor compiled a banner of flattering quotes about Freud on the occasion of his birthday. “There is a sociological aspect to psychoanalysis,” the newspaper wrote, “which is sympathetic to social progress.”16 In the end Frankfurt’s small society, with Clara Happel and Karl Landauer, emerged as historically more important than Leipzig, in no small part because it had affiliated with the distinguished Institute for Social Research.

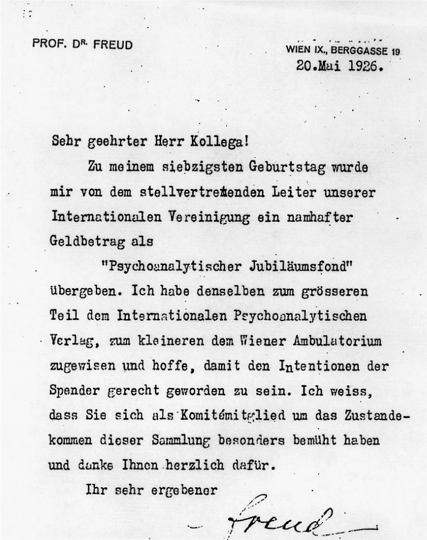

On special occasions like his seventieth birthday that year, Freud helped out with the Ambulatorium’s funding and turned over much of the 30,000 marks, about $4,200, collected by his colleagues toward a Psychoanalytic Jubilee Fund for the upkeep of the Vienna clinic (figure 26). Freud was pleased by this fund, raised largely by his pupils and his Hungarian colleague Sándor Ferenczi in lieu of gifts, and distributed its assets trusting he had been “faithful to the intentions of the donors.”17 Setting aside his cranky birthday mood, Freud thanked contributors like Marie Bonaparte whose imperial fortunes would survive even the economic crash of 1929. Freud teased her with his newest social democratic badge, the diploma certifying his honorary citizenship of Vienna (while subtly prodding her to fund a clinic in Paris). But Freud’s impulse to support the Ambulatorium was not merely charitable. The redistributive economic policies of Red Vienna’s financial decision makers, Robert Danneberg and Hugo Breitner, had taken hold, and surplus funds were invariably bestowed on institutions of social welfare. Vienna’s independent status had served it well. “The absence of slums, the clean streets, the well-tended parks … new workers’ apartments and a number of very interesting schools for children and adults” impressed a visiting young American psychoanalytic candidate named Muriel Gardiner.18

26 Sigmund Freud’s Circular Letter apportioning funds to the Vienna Ambulatorium (Archives of the Sigmund Freud Foundation, Vienna)

Muriel Gardiner would become one of the most subtle and energetic antifascist fighters of the era. By the summer of 1934, with the fascists gunning people down on street corners, Gardiner would become an extraordinary clandestine rescuer and eventually, back in the United States, protector of the Social Democrat Otto Bauer until his death. But in the mid-1920s she was still attending medical school and psychoanalytic seminars. Her memoirs of life on both sides of psychoanalysis have the effect of introducing today’s reader to the easy modes of exchange between Viennese psychoanalysts and even between analysts and patients. “Many features of analysis at that time would now be disapproved of in the United States,” she wrote in her 1983 memoirs. Gardiner was born in 1901 to a wealthy Midwestern family. She was a Durant scholar at Wellesley, active in socialist politics on campus and founder of the Intercollegiate Liberal League with friends from Radcliffe and Harvard. In 1922 she moved to Europe, first for graduate work at Oxford and then to study psychoanalysis and medicine in Vienna. Her arrival coincided with Tandler’s new social welfare system, and her interest in applying psychoanalytic understanding to education agreed with the mission of the Ambulatorium. At the time analysts “stated their opinions and tastes more openly and often discussed them freely with patients,” she observed, adding that they were “less stringent in avoiding social contact.”19 For example, Bruno Bettelheim first met his future analyst Richard Sterba in public, social surroundings and settled practical matters like the daily appointment hour and the fee quite in the open.20 For Bettelheim as for other analysands, pretreatment interviews with their prospective analysts were encouraged, even habitual, and were generally friendly experiences. Often the initial contact was an introduction by Anna Freud and Paul Federn to the atmosphere of camaraderie that was especially strong among the lay analysts. Erik Erikson, though generally ambivalent about his analysis with Anna Freud, remembered that she knitted, in session, a little blanket for his newborn son. Relaxing the social interactions between analyst and patient had political implications as well. Muriel Gardiner felt she could freely disclose her clandestine activities to her analyst Ruth Brunswick, not only because of the generally well-respected imperative of patient confidentiality but also because, she said, “I knew she shared my views.”21 And, most notably, Freud’s own casework was striking for its blithe disregard of his own technical recommendations in the areas of anonymity (not revealing personal reactions), neutrality (not being directive), and confidentiality (not sharing patient information with a third party). He shook hands with his patients at the start and finish of each session and, in almost every arena, consistently deviated from his own instructions published in 1913. Each one of Freud’s cases recorded between 1907 and 1939 reveals at a minimum his tendency to urge patients to take specific actions in their lives and also his pleasure in chatting, joking, and even gossiping with them. Much of this remains clinically controversial and, in terms of Freud’s perhaps prurient curiosity and experimentation, has led to often justified accusations of impropriety. But his overt concern for his patients and his sociability emerge as well. Even earlier in his life, in 1905, when Freud’s income barely covered his own family expenses, he helped out Bruno Goetz, a young Swiss poet with eye trouble and severe headaches. Freud read his poems with admiration, asked some questions and then said:

“Now my student Goetz, I will not analyze you. You can become most happy with your complexes. As far as your eyesight is concerned, I shall write you a prescription.” He sat down at his desk and wrote. In the meantime, he asked me: “They told me you have hardly any money and live in poverty. Is that correct?”

I told him my father received a very small salary as a teacher, I had four younger brothers and sisters, and I survived by tutoring and selling newspaper articles.

“Yes,” he said. “Severity against oneself sometimes might be good, but one should not go too far. When did you last have a steak?”

“I think about four weeks ago.”

“That is what I thought,” he said and rose from his desk. “Here is your prescription.” And he added some more advice, but then he almost became somewhat shy. “I hope you don’t mind, but I am an established doctor and you are a young student. Please accept this envelope and allow me to play your father this time. A small fee for the joy you have brought me with your poems and the story of your youth. Let us see each other again. Auf Wiedersehn!”

Imagine! When I arrived in my room and opened the envelope, I found 200 Kronen. I was so moved I broke out in tears.22

“In your private political opinions you might be a Bolshevist,” wrote Ernest Jones to Freud that year, “but you would not help the spread of Ψ to announce it.”23 Jones, as always both deferential and impulsive, tinged their correspondence with a particularly emotional quality. Here, he bursts out with his own discovery of the political nature of Freud’s thought. The spokesman for psychoanalysis divulges exactly that for which he castigates Freud. But he does not repudiate it. He understands Freud’s fascination with change and is torn between loyalty to the man and loyalty to the psychoanalytic “cause.”

The cause itself was far more politically focused than Jones understood it. By 1926 the IPA’s plans for a network of training institutes and free clinics, laid out in Budapest in September 1918, had moved forward. The alliance between socialism and psychoanalysis was sealed in Berlin when Ernst Simmel was simultaneously awarded chairmanships of the Association for Socialist Physicians and the German Psychoanalytic Association (Deutsche Psychoanalytische Gesellschaft or DPG). Next, Siegfried Bernfeld and Otto Fenichel, still two of the movement’s most politically dynamic members, officially joined the Poliklinik after leaving Vienna for Berlin. In July Bernfeld summarized their left-wing position in a comprehensive report delivered to the Socialist Physicians’ Union. The address, called “On Socialism and Psychoanalysis,” was attended by Barbara Lantos and Fenichel and most members of the Children’s Seminars, and was published in a concurrent issue of The Socialist Physician, the journal of the Socialist Physicians Union.24 Bernfeld’s essay made the case that psychoanalysis can have genuine meaning for the proletariat, but only if it is put to practical use in the class struggle. At a time when both socialism and psychoanalysis aimed to contribute to the nation’s health, medicine continued to flourish in the private hands of the bourgeoisie. Once medical practice has been completely restructured and redirected toward the working classes, then psychoanalysis would follow. Perhaps psychoanalysis did not yet benefit the public in general as much as individuals, but it did explain some phenomena (like family conflict or group dynamics) that social science could not. Logically, the insights of psychoanalysis could be brought to bear on the class struggle, with the goal of individual psychological health. To members of the Association for Socialist Physicians like Heinrich Meng, Margarete Stegmann, Angel Garma, and the Viennese psychoanalyst-politician Josef Friedjung, Bernfeld’s statement was the clearest expression to date of the argument that the two streams of psychoanalysis (the theory and the practice) have equally powerful influence. In other words, theory and practice together had a political impact that neither element alone could achieve. And as some younger DPG members and candidates, the group otherwise known as the Children’s Seminars, saw it, Bernfeld had written their song. From 1924, when the Children’s Seminars had first convened, until October 1933, when they were all forcibly disbanded, the group held 168 meetings in one another’s homes.25 Most of the meetings were devoted, naturally, to psychoanalysis and politics. But Bernfeld could explain the exact nature of a bridge between psychoanalysis and dialectical materialism that even Fenichel and Reich, who visited the Soviet Union on study tours for that purpose, were unable to build.

The enormous challenge of remaining the leader of a rapidly changing four-pronged organization—the IPA, the Berlin society, the Verlag, and the Poliklinik—fell to Max Eitingon with his masterful administrative skills. “It is very reassuring to me to know that the direction of the various organizations remains in Eitingon’s hands,” Ferenczi responded to Freud’s equally reassuring note on the Poliklinik’s post-Abraham fate.26 On January 12 a memorial was held for Abraham, the founder and first president of the Berlin society. After dignified speeches by Eitingon, Sachs, and Radó, Abraham’s portrait was placed on permanent display in the clinic’s conference room.27 Ferenczi cheered on his Liebe Freunde (dear friends), confident that together Eitingon and Simmel’s talents would find the right solution to the administrative problems left by Abraham’s death.28 Eitingon quickly appointed a presidium of Simmel, Radó, and Horney until elections could be scheduled. Loewenstein left for Paris and Alfred Gross, his replacement, moved on to Simmel’s inpatient program, the Sanatorium Schloss Tegel, only to be replaced by Dr. Witt. By then the Poliklinik staff consisted of the directors plus seven paid assistants, ten senior candidates, and about fifteen members of the Psychoanalytic Society. Each one allocated four hours daily to clinic patients whom they treated either at the Poliklinik or in their private offices. Four additional unpaid assistants each volunteered the same four treatment hours weekly at the clinic. This number four seemed to be a standard of sorts since each patient regularly visited the clinic four hours each week.

Can individual treatment be shortened or speeded up? Is the analytic hour sixty minutes or forty-five, or can it vary? How many days each week are necessary for effective analysis? Just how many months should an analysis last to be complete? Are such decisions best made by the patient or by the clinician? Like the Freud-Ferenczi epistolary debates, these moral and practical controversies were argued often, though inconclusively, by the Poliklinik staff. Though Freud had foretold in 1918 that analysts would “have to mix some alloy with the pure gold of analysis” once free treatment became widespread, the Poliklinik staff found no suitable substitute for the analytic method and condemned as metaphorically “useless … the copper of direct suggestion.” They refused to implement a priori time limits on treatment regardless of diagnosis. And while they experimented extensively with the concrete parameters of treatment, their sole definition of the course of analysis was “the process Freud created.” To justify length of treatment, Eitingon referred to the Budapest speech and compared long-term therapy of the neuroses to the treatment of other chronic illnesses like tuberculosis: “the fuller and the deeper the success, the longer does the treatment take.”29 Active treatment was an innovation, an extension of psychoanalysis perhaps, but not a replacement. Though he mocked shorter-term treatment as one of those “hyper-ingenious, forcible interventions,” which achieve little since they deviate from the path of the actual pathology, Eitingon nevertheless urged analysts to investigate fractionary, that is, time-limited or intermittent, regimens.30 “He liked to experiment with interruptions,” Franz Alexander recalled, “and the expression ‘fractioned analysis’ was frequently used.”31 A man of some contradiction and “a very charming character,” from Alix Strachey’s perspective, Eitingon viewed length of treatment as patient driven or, failing that, as a mutual decision between therapist and patient. He enjoyed developing advantageous fraktionäre schedules devised for patients like Josephine Dellisch, the impoverished Swiss schoolteacher who had befriended Anna Freud. “A month at Xmas, 3 weeks at Easter, etc., to suit her school-time—beginning in December,” Alix recorded.32 The Poliklinik staff aimed for flexible solutions to practical clinical dilemmas, and the duration of the clinical hour and length of treatment were subjected to as much debate, or more, in the 1920s as today. Daily sessions were ideal, but since so many of the patients were working, analysis three times a week was more widespread. By 1926 the three-hour weekly treatment schedule was found generally adequate and retained as standard practice in Berlin. Ten years later, as founder of the new Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis, which he modeled on his Berlin experience, Alexander still insisted on flexibility, that treatment be adjusted to the patient and not the other way around. Even if it meant curtailing the analytic experience, he said, “it is advantageous at times to change the intensity of the therapy by alternating the frequency of the interviews or by temporary interruption of the treatment.”33

How long should an analytic session last? If treatment is an everyday part of life, an hour like any other work hour of the day, then maybe a thirty-minute session is just as natural a unit of time as the full sixty-—minute hour. Sixty minutes had been the standard length of a session until the 1920s when Karl Abraham and the Poliklinik staff took it up as yet another controversial debate. At first the analysts intended to “systematically and in every case reduce the length of the analytic sitting from one hour to half-an-hour,” Eitingon wrote, because of their patients’ crowded work and family schedules. Instead, each patient’s session was set individually, with a total amount of minutes ranging from forty-five to sixty minutes. The deciding factor was the patient’s responsiveness to “discipline”—perhaps another word for motivation. For one so accepting of mankind’s Rousseau-like natural self-regulatory talent, Eitingon’s statement that “despite their neuroses … [self-disciplined people] are not seldom to be found in Prussian Germany amongst civil servants and others” was sarcastic at best. Is the “discipline” a natural internal human motivation toward health? Or is it a response to external motivation, such as a fractionary schedule? Which would make greater sense clinically? As their friends from the Frankfurt School would say, the answer lay in the dialectic. An analytic interview, or session, could last from forty-five to the full sixty minutes since, in theory at least, only a balance of the practitioner’s clinical assessment and the patient’s discipline would lead to an appropriate scheme. Nevertheless according to Alexander, Eitingon’s initial experiments with half-hour interviews proved “unsatisfactory” and what would become the standard fifty-minute analytic hour was instituted as the official norm. Patients were seen three to four times weekly, or more, with no time limits preestablished for ending the analysis. The Poliklinik was open from 8:00 A.M. to 8:00 P.M. daily. About three hundred analytic (full) hours were allocated weekly to clinic patients.

The possibility of modifying the length of the clinical hour also attracted the Viennese. In particular the staff of the Ambulatorium’s later experimental Department for Borderline Cases and Psychosis found that the full sixty-minute analytic hour produced insupportable agitation in the patient. Reducing the session by a mere fourth, or fifteen minutes, seemed to contain the individual’s anxiety and generally yield a more productive interview. But it would take at least another twenty years for the abridged time frame, the fifty-minute hour, to enter into the mainstream of psychoanalytic culture. After the Second World War the French psychoanalyst Sacha Nacht reintroduced the shorter forty-five minute hour and the three-time-weekly treatment schedule to willing practitioners at the clinic of the Société Psychanalytique de Paris.34

Since measuring the clinical hour had come under such scrutiny, naturally the duration of a complete course of treatment was examined too. How long should psychoanalysis last? How rigorously should analyst and patient hold to the daily schedule? Sándor Ferenczi had explored the clinical theory behind “fractionary analysis,” the interval-based schedule now considered a precursor to today’s “short-term” planned treatment and Eitingon had applied it.35 At the same time, Ernst Simmel reintroduced experiments with effective, two- to three-session treatment he had started during the war. Later taken up in Vienna, fractionary analysis was not interminable but could be interrupted or divided into segments dictated by the patient’s life. A pregnancy, a resistance to clinical change, military conscription were just some of the indications for legitimately interrupting the course of treatment. Unlike other therapeutic actions, a deliberate “fractionation” signaled either the end of treatment or simply a hiatus during which patients would practice (perhaps presaging Margaret Mahler’s developmental theory) the options gained from new insights and then return—or not—as they chose. Analysts and their patients could set a mutually acceptable date for “termination,” the planned end of treatment. Of course, the method of fractionary analysis was statistically satisfying as well because it allowed the analysts to document and count a type of “success rate”: a completed analysis was a successful one, while the more ambiguous ones were merely fractionary—not failed.

Gratifying patients’ father fantasies—and then inducing patients to renounce them? This sort of freethinking question could be asked and even acted upon by the Poliklinik’s experimenters. The Poliklinik analyst’s independence from financial interest in the patient offered both parties hitherto unknown clinical freedoms. In a manner reminiscent of Ferenczi’s efforts at “mutual analysis,” both analyst and patient could assess whether transferences changed according to the status of the patient and could use their freedom to experiment with these new forms of treatment. As Eitingon said, “in private practice [this] could never be undertaken, because it is only rarely that life allows so costly a performance.”