“The very group of patients who need our treatment are without resources”

“THE CENTERS immediately became so overcrowded,” Reich said of Sex-Pol, “that any doubt as to the significance of my work was promptly removed.”1 Once the Vienna newspapers announced that the new sexual hygiene clinics for workers and employees had opened, the work of the clinics took off. In January 1929 Reich decided to expand the Sex-Pol network of free community clinics, and add longer-term individual psychoanalysis to the brief contact of the outreach missions. The clinics gained ample encouragement from prospective patients who, for whatever reason, did not go to private therapists or other consultation centers in Vienna, nor to the Ambulatorium where Reich was still assistant director. From his office on the fourth floor of one of Vienna’s ornate stuccoed buildings, equidistant between the Ambulatorium and the Allgemeine Krankenhaus, Reich coordinated the network’s activities. By now six clinics had opened in different districts of Vienna, each clinic directed by a physician. Three obstetricians and a lawyer volunteered to be on call. Reich, who most enjoyed his position as scientific director but whose popularity as an analyst never abated, had to schedule a second daily consultation hour because at least ten people at a time would wait their turn to see him during his hour reserved for counseling. Thorough diagnostic consultations took about half an hour per person, however, and many prospective patients required considerable assistance.2 The four psychoanalytic colleagues from the Vienna society who joined Reich—probably Annie Reich and Grete Lehner Bibring, with Siegfried Bernfeld and Otto Fenichel on their trips back from Berlin—were similarly beleaguered. Their lack of time became particularly acute once the outreach lectures started, and Reich was impatient and demanding. He still thought of his psychoanalytic peers as collaborators in the struggle for human liberation, but was concerned that their commitment would waver under pressure. Nevertheless Reich reassured his Viennese colleagues that their ongoing activism and support was still effective.

Reich’s professional image was considerably less well-established, however, among most of the Americans staying in Vienna for their psychoanalytic training. They were suspicious of Reich’s membership in the Communist Party. One young foreign candidate warned O. Spurgeon English, a New Yorker then in analysis with Reich, that Communism was dangerously contaminating. “When I returned to the United States, as a result of exposure to [Reich],” he cautioned English, I “would not be able to obtain a position in any American university.”3 One evening, when English took his friend’s advice and asked Reich to explain how his political activities affected psychoanalysis, Reich suggested he speak instead to Helene Deutsch as director of the Institute. Reich was nervous about leaving his reputation in one analyst’s hands, especially since he and Deutsch had quarreled over practice issues at the technical seminar. Nevertheless Deutsch stated her “complete confidence” in Reich and told English that she had “never seen any evidence that his political views disturb his ability as an analyst.”4 Either Deutsch was being generous or she simply agreed with Reich’s politics. By then some of Reich’s more outrageous capers had caused even the generally sympathetic Arbeiter-Zeitung to denounce his “backfiring maneuvers.”5 The newspaper accused Reich of having tried—and failed—to install a Communist cell in Ottakring, a working-class neighborhood, and of misusing the name of the Social Democratic Party.

Not that Reich had abandoned his belief in the union of psychoanalysis and left-wing politics. He warned that the struggle for human liberation could only be maintained if “the discoveries and formulations of psychoanalysis are not watered down and that it does not gradually, without its apologists realizing what is happening, lose its meaning.” His own Socialist Association for Sex Hygiene and Sexological Research would be challenged by just this crisis. Yet Reich still emphasized that “the proper study of psychoanalysis is the psychological life of man in society” in his essays written between 1929 and 1931. His class-based analyses placed workers’ sexuality within a dominant bourgeois culture. Impoverishment of worker sexuality was a form of subjugation caused by enforced living conditions, especially harmful to young people whose energy could not—and should not—be simply sublimated by sports events. After a two-month pilgrimage to Moscow (where his lectures failed to win over local audiences from the Communist Academy) in 1930, Reich was all the more convinced of the need for a universal sexual revolution. “The history of psychoanalysis in bourgeois society is connected with the attitude of the bourgeoisie to sexual repression, or, to put it another way,” Reich stated, “to the removal of sexual repression.”6 Finally he asked with pointed candor if “the bourgeoisie [could] live side by side with psychoanalysis for any length of time without damage to itself?” If psychoanalysis and bourgeois society got together to make psychological care genuinely accessible to the community, the result might look like his own free clinics.

Reich urged his psychoanalytic partners toward ever more frank and intimate communication with the people they treated on an individual micro level. At the same time, he proposed that a “practical course in social economy” or academic sociology would benefit them on a macro level. Sound social reform would emerge from this form of psychoanalytically blended social work. Increasingly impatient with academic city planners and with “official sociology still compiling dead statistics,” Reich viewed social work as a more direct and meaningful application of the social sciences than experimental research. Social science research on its own was too abstract and already a fairly useless exercise, with few publicly redeeming qualities except perhaps in its practical applications. Sociologists would learn much more about the frank realities of human life “not at their university offices but at the sickbed of society, on the streets, in the slums, among the unemployed and poverty-stricken,” Reich wrote. Typical of his pronouncements on the deteriorating human condition, Reich demanded “practicality” even from an academic discipline and prescribed at least six years of pragmatic experience as “social workers” for sociologists, “just as physicians gain their [profession] through six years of hard work in laboratories and clinics.” In this realm of social work Reich followed and then extended Freud’s political thought. Like an analysis that frees the individual from inner oppression and releases the flow of natural energies, so—Reich believed—the political left would free the oppressed and release their innate, self-regulating social equanimity. By coincidence, Reich’s extended his efforts to build up Sex-Pol just when his activist colleague Ernst Simmel was renewing his rounds of fund-raising for another controversial institution (supported by Freud), the Schloss Tegel inpatient facility.

“The very group of patients who need our treatment are without resources, precisely because of their psychoneurosis. I am constantly receiving letters from morphine and cocaine addicts and alcoholics begging for treatment, which mostly I cannot give them, or only at personal sacrifice,” Simmel pleaded to Minister of State Becker.7 Clinically, the sanatorium had afforded indigent people a total therapeutic milieu whose “aim [was] to produce in our patients responsibility for themselves.”8 Becker was then the Kultus Minister, the Prussian minister of art, science, and education who professed to be responsive to Freud’s work and honored by his annual presence in Berlin-Tegel. Would Becker and his important officials, however, agree to future funding of the sanatorium? Freud, who found the Tegel facility enormously beneficial to himself and more generally to psychoanalysis, resolved to explain the hospital’s financial predicament to Becker in person. In a special meeting between himself, the minister, the Tegel staff, and Simmel, Freud brought back almost word for word, and certainly in concept and in tone, the final challenge from his Budapest speech. “It is difficult to support this work by private means alone,” Simmel recalled him saying, “and its future depends upon whether you, for instance, Herr Minister, help us support such work.”9 Ultimately Freud held that, since the representatives of the state wielded considerable power regardless of the current regime, and that by definition they would remain unmoved by the plight of the common people, the analysts were responsible for providing their government with enlightened guiding principles. And as the hospital’s financial crisis seemed only to become worse, Freud’s response was to declare the urgency not only of preserving the institution but also of enhancing it with research and training programs. Simmel had actually planned to expand the Schloss Tegel facility, now a semiclosed institution, and develop a locked unit for people with severe psychoses. But, like most such establishments, the sanatorium was caught in a three-way confrontation between the psychoanalysts’ experimental and humanitarian concerns on the one side, establishment psychiatry on another side, and the market imperatives of private land owners on a third. The von Heinz family, landlords of the nearby Schloss Humboldt, largely dispensed with charitable leanings and soon objected to the prospect of lower property values, for them a far more terrifying prospect than freely roaming psychiatric patients. “As most people would shrink from the idea of settling near an establishment for the mentally ill,” the landlord wrote to Simmel, “the nature and purpose of which, after all, cannot be hidden, my land would lose its value in an undesirable way.”10 The government agreed. Despite Becker’s individual declarations of support for Simmel’s project, the German government fully concluded, along with the landlord, that such an institution would harm investment and real estate speculation. Meanwhile Dr. Gustav von Bergmann, medicine director of the Berlin Charité, rendered a negative opinion in essence parallel to Julius Wagner-Jauregg’s verdict on the Ambulatorium in Vienna. “It’s not the misgivings of the medical faculty that are crucial,” he said in casting his vote against the Tegel Sanatorium, “but the conviction that the psychoanalytic worldview is as one-sided as the purely somatic…. The principle of the psychoanalytic clinic as a program—as I see it—cannot be endorsed” even if psychoanalysis has merit when combined with medical therapies.11 With or without the closed unit, state support was withheld.

A fresh, younger group of supporters rallied to Simmel’s cause and started to rebuild the clinic’s financial base with a series of fund-raising programs. Marie Bonaparte undertook a campaign to raise an endowment, similar to Eitingon’s concurrent crusade to rescue the Verlag, in order to save the Tegel facility. She had stayed at the sanatorium and had, as Freud said “become intensely interested in the institution and decided for herself that it must not go on the rocks.”12 The French psychoanalyst René Laforgue suggested that IPA members should buy stock, even a very small amount, in the corporation. But by then the good faith of IPA benefactors like Pryns Hopkins was dangerously stretched. In March Hopkins had no sooner “given £1000 to the London Clinic [than] the Princess [Marie Bonaparte] asked for money to save Simmel’s sanatorium.”13 Freud sent out his own plea letter worldwide and augmented his annual contribution, but the prospect of ongoing aid remained tenuous. Still, Anna, who had lived at Tegel for a few weeks while her father recovered from cancer surgery, remained optimistic about the sanatorium’s future. Writing from Tegel, she conveyed to her friend Eva Rosenfeld how both peace and confusion descend simultaneously on the mind during analysis. In contrast, true country calm gives off enough peacefulness to help the mind rebound from city stress. “Tegel is … an island of safety in the midst of city traffic … ideal and more beautiful than ever,” she wrote to Eva, who would move there late the next year. At Anna’s urging, Eva would also start a period of fee-free analysis with Freud when he returned to Vienna. Meanwhile, prospects for Tegel’s survival improved. “Dr. Simmel is in high spirits and full of hope,” Anna reported.14 And two weeks later she wrote to Eva about Laforgue’s plan. “We are trying to found Tegel Incorporated, but are lacking a few rich people who could buy shares. I hope we bring it off.”15 The appeal was graceless and largely ineffectual, even among the London analysts who had valued the shares at £25 each.16

Anna Freud lost little time at Tegel. She taught one seminar at the Berlin Institute and another three-day course in child analysis at Tegel. She was generally pleased that some of the Berlin analysts, including Melitta Schmideberg (Melanie Klein’s daughter), Jenö Harnik, and Carl Müller-Braunschweig, had met with her at Tegel—they had even rented a car for this October trip to the country—but Anna still felt like a stranger among them and far preferred her Vienna group. In the ongoing dispute between the Berliners and the Viennese over everything from human character to aesthetic pleasure to analytic technique, Anna caught on quickly to the Weimarian penchant for the “usable and useful” versus the Viennese inclination toward the “easy and pleasurable.” Personally, though, she despised what she called the efficient Berliners’ “ideals, their houses and antique furniture and conveniences” in favor of a more rural, simpler, and perhaps more communal life.17

The newest outpatient clinic was scheduled to open in Frankfurt, this one particularly exciting for its association with the candidly Marxist Institute for Social Research (Institut für Sozialforschung). Keeping up with the steady expansion of local analytic societies, Simmel’s colleagues and long-time friends Karl Landauer and Heinrich Meng of the South-West German Psychoanalytic Society founded their psychoanalytic institute and its companion clinic in Frankfurt in February 1929.18 In a bold and perspicacious move, Landauer decided to house the clinic on the premises of its intellectual partner, Max Horkheimer’s Institute for Social Research. Now, as “guest institute” of the Institute for Social Research, the Frankfurt Psychoanalytic Society became, in a roundabout way, the first psychoanalytic group with enough status to be connected to a university. The University of Frankfurt, which the socialist theologian Paul Tillich (appointed as chair of philosophy the year before) called “the most modern and liberal of the universities” in the late 1920s, was a natural site for this association.19 To celebrate the alliance of their clinic with the Frankfurt social scientists, Landauer invited all his IPA colleagues worldwide to participate in a series of inaugural lectures. They were delighted. Even Ernest Jones was so pleased that he announced Landauer’s invitation to “the opening of a Psycho-Analytic Clinic in Frankfurt” to his colleagues of the British society and was tempted to show up from London.20 The roster of illustrious speakers from Berlin attracted local media attention, and the psychoanalysts’ ideas received generally positive reviews in the Frankfurt press. The Frankfurter Zeitung in particular devoted an entire issue of its supplement Für Hochschule und Jugend (For College and Youth) to the new series of lectures attended by physicians, students, and teachers at the Institute for Social Research. On February 16 Sándor Radó, Heinrich Meng, and Erich Fromm each delivered an inaugural address as a prelude to the Institute’s forthcoming programs.

Erich Fromm, then head of social psychology department at the Institut für Sozialforschung and a lecturer at the psychoanalytic institute, lent an uncommon passion to his speech of the opening day ceremonies because he too, like his Frankfurt colleagues, had researched a fused external and internal understanding of mankind. “Dr Erich Fromm (Heidelberg) spoke of the possibility of applying psychoanalysis to sociology,” reported the Frankfurter Zeitung, “for on the one hand sociology is concerned with human beings and not the mass mind, while on the other hand human beings exist, as analysis has always recognized, only as social creatures.”21 The reporters summarized his essay well. In Fromm’s talk titled “The Application of Psychoanalysis to Sociology and Religious Studies,” concurrently published in the analyst’s pedagogical journal, he proposed that, from the beginning, psychoanalysis had understood that “there is no such thing as ‘homo psychologicus’.” The true challenge lay in grasping “the reciprocal conditioning of man and society” and that social relations are parallel to, not the opposite of, object relations.22 Fromm’s courses at the Institute would unavoidably present two apparently antithetical positions, but the difference between sociology and psychology was really just methodological, a question of form and not content. Like all the teaching analysts, Fromm outlined how his course material was based on data from the clinic. If the analysts could compare observations and plumb patients’ case histories from the clinic, Karl Landauer warranted, the psychotherapists’ chances of success would be determined by objective, empirical knowledge and not by so-called intuitive understanding. This approach existed already in Berlin, Radó had said in his opening remarks, where over one hundred “free treatment analyses are carried out everyday,” not including the training analyses, by the Poliklinik’s twelve lecturers. Now Frankfurt had the opportunity, as only the second psychoanalytic institution in Germany, to meet the population’s need for treatment as well as the psychoanalysts’ need for clinical data.

The Frankfurt analysts were caught in an interesting predicament. On the one hand they had too little room for a full-fledged treatment bureau until the next year and too few faculty to constitute a training facility. Conversely, their impressive affiliation with the Institut für Sozialforschung made them a collective center for psychoanalytic information, and the faculty was in great demand for public lecture tours, presentations in community education centers, and continuing professional education courses for lawyers, social workers, teachers, psychologists, and doctors. Bernfeld’s Frankfurt speech on “Socialism and Upbringing” was the first in a series of four inaugural lectures. Conventional bourgeois education, Bernfeld explained, demands conformity and favors a sort of indoctrination into social norms. In contrast, socialists believe that education is a process of learning about one’s self and others through personal struggle (hence psychoanalysis) and the development of group consciousness.23 Anna Freud spoke about pedagogy as well, and Paul Federn and Hanns Sachs followed with two more open lectures on the meaning of analysis in sociology, medicine, and the mental sciences. Among themselves they bickered. Anna Freud complained to Eitingon that “Bernfeld draws the wrong conclusions from correct observation. Otherwise one might spare oneself the trouble of therapy.”24 And they also made amends. “What a warm heart you have, you dear man,” Jones exclaimed in a burst of collegial reconciliation with Eitingon.25 But publicly they stood as a united vanguard for psychoanalysis. The Frankfurt group centralized their educational advisory bureau just as their colleagues at the Ambulatorium had in Vienna, and added a research coalition of psychoanalysts and medical internists to teach their allied professions how to apply psychoanalytic technique. The constant intermingling of sociology with economic and psychoanalytic theory in discussions, lectures, research, and clinical treatment produced an exceptionally vibrant intellectual community. “There were personal, academically fruitful contacts between our lecturers and the theologian Paul Tillich,” Heinrich Meng recalled as an example. In “one of his topics of discussion … [Tillich] established how strongly the young Marx emphasized humanism as the core of socialism.”26 At the Institute’s peak many of its leaders focused their studies on the nature and roots of fascism and, in particular, on the rise of National Socialism. Unfortunately this intellectual pursuit was alarmingly prescient, and, with Nazi power increasing daily, their discussions were either futile or cause for exile. Four years later the inevitable choice would be exile.

In the weakening economic climate in Europe now also affected by the American Depression, Ernest Jones had little option but to appeal to the loyalty of the British society members in order to sustain the work of the London clinic. Late in October Jones proposed, as a cost-saving measure, to dissolve the formal barriers between the four components of the society. This was a logical decision since the same core group of members directed the Institute, edited the journal, chaired society meetings, and volunteered at the clinic. Besides, officers of the society held onto their titles and put them to use as enhanced connections to established academic and medical groups. Writing to Max Eitingon, Jones dismissed his friend’s concern about the London clinic’s viability by reminding him that Sylvia Payne, as the new “Business Secretary,” consolidated all correspondence for the society, Institute, and clinic under her jurisdiction, while Edward Glover coordinated research and public programs.27 For the nonmedical people these institutional contacts were particularly important tokens of legitimacy. However the present situation called for efficiency over prestige, and all members of the British society were unilaterally appointed as clinic assistants. All staff would treat one patient daily at the Gloucester Place facility or, as in the other societies, render an alternative but equivalent amount of service or money to the Institute.28 Jones relished the plans afoot to fuse the society, the Institute, and the clinic into a single unit and, in virtually identical letters sent off to Freud and to Eitingon, described how he would “consolidate the new profession of psycho-analysis.”29 The most original element of the project—Jones called it “revolutionary”—placed lay analysts at the clinic in the same capacity as the regular staff. Thus as in Berlin and Vienna in different times, new clinical knowledge was discussed at the society but implemented only at the clinic.

While other analysts were formulating theories of child or adult development, Erik Erikson envisioned a longitudinal pathway through human life and established the markers for a steady transition from infancy to old age. Handsome and courteous, Erikson was an appealing young man. He had startling blue eyes, a square jaw, and the attentive demeanor of a born clinician. In the traditional style of the German intellectual, he kept a trim mustache and combed back his wavy blond hair. Erikson’s now legendary psychosocial stages (as opposed to Freud’s psychosexual stages) were conceived when working with adolescents at the Ambulatorium and were based on his experience there. His work with teenagers was supervised by August Aichorn, while Helene Deutsch and Eduard Bibring oversaw the treatment of his first adult patient. Erikson later said that he had decided to pursue a training analysis with Anna Freud once he became convinced, in his work with children at Heitzing, that psychoanalysis was compatible with art and had a strong visual component. Even today Erikson’s eight stages are essentially a visual representation of human psychological development. The “stages” are charted diagonally rather than vertically to show that the sequence of stages, each of which chronicles how an individual appropriately resolves the struggle between their inner self and their outer, environmental or cultural demands, are “present at the beginning of life and remain ever present.”30 His model proposes that each stage has a healthy and an unhealthy resolution, notably the “Identity vs. Diffusion” of adolescence, and it assumes that this resolution lies in conforming to cultural norms such as independence from family, individualism, and personal achievement. Yet for all his emphasis on the “social” aspect of development and the construction of individual identity (the autobiographical undercurrent is conspicuous here), the strength of Erikson’s theory actually lies in the tools it gives the therapist for helping individuals explore their inner worlds.

Anna Freud was running three seminars at the Ambulatorium at the time, and had taught each of these courses at least weekly since 1926. Nearly every notable psychoanalyst from Vienna attended either her informal Kinderseminar31 for younger analysts at the clinic, her weekly pedagogy seminar on merged psychoanalytic and educational techniques (largely drawn from her work at the Heitzing School) or her Technical Seminar on Child Analysis at the society’s Training Institute. In her tireless pursuit of explanations of childhood psychological disorder, Anna invited experts on each stage of the life cycle to make presentations to the senior analysts who sat around a table while junior analysts sat behind them or stood. Aichorn, for example, taught adolescent psychology and juvenile delinquency. At another seminar Willi Hoffer presented a full case study of a child in analysis complete with behavior, dreams, and fantasies. Reich conducted a similar lively program analyzing case studies of adolescents and adults.

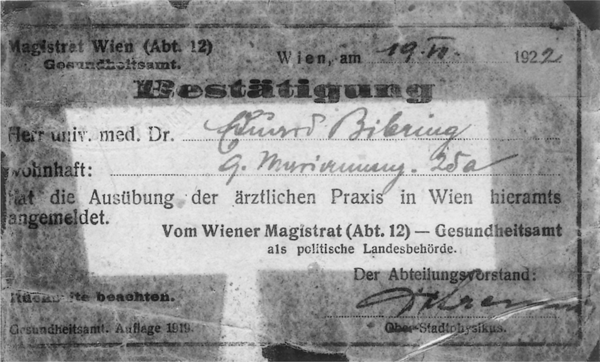

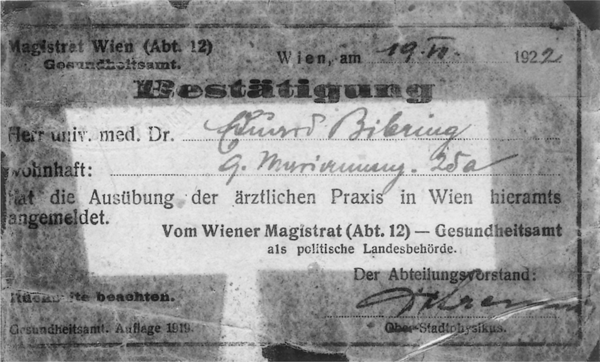

Heinz Hartmann, who was later to preach psychoanalytic orthodoxy under the guise of “ego psychology,” had just returned to Vienna from several years at the far less conventional Berlin Poliklinik. Hartmann and his colleague Paul Schilder promoted a dual, or synthesized, psychoanalytic and biological approach to mental illness and wanted to test this formula in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Despite the omnipresent lure of Wagner-Jauregg’s powerful Psychiatric-Neurological Clinic where both had trained in the pathological-anatomical model of treatment, the two psychiatrists hammered out the plans for a new experimental department at the Ambulatorium. Specifically designed to treat adults with borderline and psychotic symptoms, the new section marked a milestone in improved relations between the psychoanalysts and the medical fixtures of native Viennese psychiatry. Some fifteen years earlier, during and just after the end of World War I, the psychiatric approach to adults with forbidding psychological diagnoses had shifted from accusations of malingering to a more sympathetic treatment of a disorder called war neurosis. Psychoanalysis had triumphed as the preferred form of treatment in all but the most conservative medical circles and had gained remarkable popularity even within military medicine. Presumably the same might happen now with other disorders. Unfortunately, no sooner had Schilder inaugurated the special clinic at the Ambulatorium in March, with plans for a systematic experiment in the psychotherapy of the psychoses, than he accepted a job offer from Adolf Meyer and left for the United States. Schilder’s friend Eduard Bibring took over as the clinic’s new director in September. Bibring too was a hospital-trained psychiatrist (figure 30), but, more important, he had been part of that lively group of Tandler’s anatomy students who one afternoon in 1920 had visited Freud and emerged as his newest protégés. This same energy characterized Bibring’s management of the new clinic, a confident initiative in keeping with Red Vienna but very much ahead of the times. Even visitors from America could see this. “The eleven-year-old republic of Austria,” observed William French of the Commonwealth Fund,” has built up a system of … care that is distinctive, flexible, and increasingly effective.”32

If Bibring had not enhanced the Ambulatorium’s newest therapeutic program, the Department for Borderline Cases and Psychoses, Hartmann and Schilder’s psychoanalytic treatment model for people with schizophrenia, would not have attracted Ruth Brunswick, who joined in 1930. With Brunswick’s expertise in treating severe depression and her unique compassion for people marginalized by mental illness, the clinic’s work took an even more progressive direction. The standard in-depth evaluation of neurotic adults was eliminated in favor of a shorter, symptom-focused assessment questionnaire. Had the patient heard voices, or had visions, hallucinated? In order to forestall bias, a team of clinicians studied the patient’s responses and then chose one of three possible treatment venues. First, patients who needed an extra questionnaire to confirm the presence of mental disease were remanded to the regular adult section. A distinction had to be made between, for example, the organic hallucinations of the schizophrenic and the self-medicating alcoholic hallucinosis of the severely depressed. For patients to qualify for treatment in the psychiatric section, their psychotic or borderline symptoms could not be ruled out pending intensive scrutiny, and so they remained under observation and were eventually treated accordingly. Second, those who required an individualized treatment plan suited to their diagnostic category were offered less purely psychoanalytic forms of psychotherapy. Someone with a fragile hold on reality would tolerate with difficulty the anxiety stirred up by daily hour-long regimens of free association. And, technically, psychoanalysis could be modified: the full hour could be shortened to forty-five minutes, frequency reduced from five times to three times weekly, and perhaps the couch could be forfeited for a chair. Third, the analysts assumed the highly contestable position of allowing staff to offer classical psychoanalysis selectively to borderline cases or to people with incipient psychosis. Naturally aware of debates in this field, Eduard Hitschmann reported that nearly seventy cases of schizophrenia had been treated over ten years. Even the municipal hospital’s psychiatric clinic, Wagner-Jauregg’s own domain, referred patients. So too did the law courts: court officers were entitled to commute the sentence of offenders who agreed to manage their uncontrollable behavior with psychological treatment in lieu of incarceration. Social welfare centers, neighborhood physicians, and sanitoria where staff believed in a benign approach to mental illness sent referrals. Of course the Ambulatorium’s own outpatient section sent over patients whose neurosis leaned toward psychosis. In retrospect, Bibring and his colleagues were naive in assuming that schizophrenia could be treated by analysis alone. But colleagues in Berlin were discussing this approach, and certainly in Budapest Sándor Ferenczi was experimenting with ingenious, if controversial, modifications in method that went way beyond individual style.

30 Eduard Bibring’s license to practice medicine, issued in 1922 (Archives of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute)

Under very different political circumstances, Sándor Ferenczi was also exploring options for instituting a clinic in Budapest. His colleagues in Vienna, Berlin, and London had successfully acted on the obligation to accommodate the needs of poor and underserved people for mental health services. Budapest’s chronically inadequate public and private resources resulted in the actual loss of life, Ferenczi implied, in his overtly polemical introduction to a published case report. Ferenczi promoted the pamphlet, “From the Childhood of a Young Proletarian Girl,” as a combined clinical summary and plea for understanding. In the gruesomely fascinating notes recording her first ten years of life, the nineteen-year-old daughter of an alcoholic underemployed father and despairing mother explored, with extraordinary precision, the relationship between social class and human misery. Ferenczi had been unable to stop the suicide of his precocious patient, but he did publish her Diary and let stand what Imre Hermann fondly called “subversive words for 1929.”33 “Rich children are lucky,” the young diarist wrote. “They can learn many things, and [learning] is a form of entertainment for them … and they are given chocolate if they know something. Their memory is not burdened with all the horrible things they cannot get rid of. The teacher treats them with artificial respect. It was like this in our school…. I believe that many poor children learn poorly or only moderately for similar reasons and not because they are less talented.”34