“Male applicants for treatment [were] regularly more numerous than female”

IN MARCH of 1932 the Ambulatorium celebrated its tenth anniversary by publishing its most extensive report to date on those who were “given the opportunity of undergoing an analysis, free of charge.”1 Some of Hitschmann’s most trusted analysts had already met to discuss how the clinic’s record should be promoted, and persuaded him follow the Berlin Poliklinik’s example. An initial account would be published in the IJP, they decided, and followed up with a separately printed summary released as a brochure. The report was meant to detail how well the Ambulatorium had carried out Freud’s 1918 mission statement, but it marked the clinic’s role in sustaining Red Vienna as well. The Ambulatorium had become known, Hitschmann wrote, as an independent center where farmers, professionals, students, workers, and others who could not afford to pay for their therapy had been treated at no cost since 1922. The report also suggested that, as Helene Schur recalled as well, Vienna had become “a very progressive city [and] the health stations were excellent” in the early 1930s, despite the analysts’ early encounters with a hostile medical establishment. “The hospitals were really very good,” she said. “People had insurances when they worked; people who didn’t have money were treated for nothing.”2 Even in the larger political arena the Social Democrats retained a safe 59 percent of the Austrian vote. For the first time, however, the National Socialists (the Nazi Party) participated in the municipal elections and gained just over 17 percent of the vote, with the remaining 20 percent going to the old-fashioned Christian Socials.3 Nevertheless, several psychoanalysts who were also social democratic representatives (like Friedjung and Federn) managed to remain in power despite the election of the conservative Engelbert Dolfuss as chancellor. Hitschmann and Sterba now favored supplementing their earlier 1925 account of the Ambulatorium’s public health effectiveness, arguing that new data and some fresh interpretations would enhance the clinic’s role in the city’s social welfare system. That last report had been timely but dry and safe. This new publication would feature crisp statistical tables and categories, with patients counted variously by diagnosis, age, and sex and by occupation (or social class). Unfortunately, the document was unexpressive and dull and the statistical categories that promised to provide solid evidence of the Ambulatorium’s impact on social welfare simply listed numbers. The tables counted applicants by pairs of years (from 1922/23 to 1930/1) and added them up into “grand total” sums. On average, the Ambulatorium registered between 200 and 250 applicants each year. Hitschmann paid little attention to the difference between “consultation/intake” and “treatment,” and his few cross-tabulations make clear the effort involved in producing even this amount of information. In its own way, though, the information was accurate: the Ambulatorium’s patient data provided evidence of an unexpected gender inequality in the use of psychoanalysis. Hitschmann had published the first (and perhaps only) longitudinal study confirming that males were more frequent consumers of psychoanalysis than females.

“Male applicants for treatment [were] regularly more numerous than female,” Hitschmann said. He had sorted the applicants by age group and by gender and found that almost twice as many males had applied for treatment as females. Similarly, when he grouped clinic applicants by occupation and then gender, he found that males outnumbered females in almost all categories including school children and students. Over the last ten years 1,445 males had requested psychoanalysis, whereas only 800 applicants were female, less than half the number of males. The ratio of male and female applicants, constant for the Ambulatorium but still surprising to read today, was particularly striking within the twenty-one to thirty year old age group. In 1923 and 1924, when Bettauer’s newspapers unabashedly promoted psychoanalysis as a remedy for the loneliness of youth, exactly half as many females (118) applied for treatment as males (236). The male majority was not without logic. In Red Vienna most social democrats, from Tandler to Reich to Hitschmann, commonly implied that the virile quality of psychoanalysis would free men to pursue occupations, self-fulfillment, and independence. Impotence, like other male illnesses, was related to the economy and carried little moral charge. “People do not die from deadly bacteria alone,” Simmel contended, “but rather from the fact that anyone exhausted from brutal exploitation by industry becomes easy prey for whatever germs they happen to encounter.”4

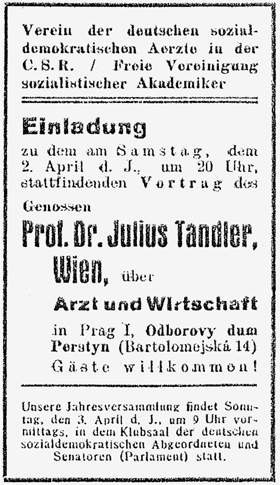

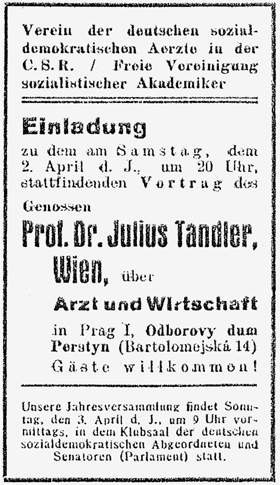

At the same time Simmel’s friend Julius Tandler evoked the images of healthy working men (and nursing women) to boost an ardent pro-family message underlying his speech on the democratic relationship between the physician and the community. “Comrade” Tandler’s speech on medicine and the economy was advertised (figure 33) not by one but by two of Berlin’s socialist organizations, the German Social Democratic Physicians and the Free Society of Socialist Academics. The Ambulatorium itself was a hardworking place, a basement of a hospital cardiology clinic. Patients were “salaried employees, working class, professional, domestic service, teaching, without occupation, pensioners, and [university] students.” In other words, they were often male and employed, precisely not the clichéd images of pale rich women with vapors. Impotence ranked as the clinic’s most frequently recorded diagnosis, reiterating how psychoanalysis would give men—who already had more social freedom than women—even greater license to address sexual dysfunction, improve their sex lives, and, coincidentally, produce families and rebuild a vigorous state. The data could suggest that Freudian psychoanalysis was more acceptable to males simply because it was so openly “about sex.” Not that women were ignored. It was one of the accomplishments of psychoanalysis to assert that women did have sexual responses. That women of the “lower” classes also had sexual autonomy was an even more daring idea. Whatever larger gender ethos facilitated men’s access to the Ambulatorium, the clinic’s own disposition to treat women as equally sexual was avant-garde.

33 Advertisement for Julius Tandler’s lecture in the Socialist Physician, spring 1932 (Library of the Center for the Humanities and Health Sciences, Institute for the History of Medicine, Berlin)

The two exceptions to the male plurality in Hitschmann’s tallies can be found in the occupational categories of “domestic service” and “no occupation.” Here women (296) appear over four times more than men (66). Women’s enrollment in Tandler’s maternal/child consultation centers or other family assistance programs probably accounts for the increase. The community lectures in child development, the support of the municipal social workers, and the local newspaper articles were among most visible forms of promotion for psychoanalysis, and many were targeted to women. Consequently, poor women or those with “no occupation” sought assistance not for hysteria but for relief from the same problems plaguing the men—depression, lack of occupational satisfaction, and sexual dysfunction. By the early 1930s an interesting and unexpected profile of the Ambulatorium’s patients had emerged. For one, the male and female clients had largely the same psychological complaints (and, presumably, the same sense of sexual dysfunction). And, second, the clinic population was eclipsed by young adults regardless of gender or social class. In the ten years covered by the report, the twenty-one to thirty year olds were the only group that reached over one thousand (1,083 specifically). They were by far the largest single classification of consumers and the only group that came close, though a full 50 percent smaller, were the thirty-one to forty year olds (537). At either end of the age curve after that, children under age ten and elderly people ages sixty-one to seventy were seen and counted, but represented only a small fraction of the total patient population. In 1926 and 1927, peak years for children and seniors, Hitschmann counted seven male and five female children and five seniors. In contrast, no seniors and only a few children were counted in either 1922/23 and in 1928/29. It is possible that the child patients, who were treated at the separate Child Guidance Center, were undercounted in this report.

Vienna’s Child Guidance Center was thriving, now that August Aichorn had taken over, on a consulting basis, after retiring from public service.5 The Heitzing School had closed and, along with it, Aichorn’s periodic teaching there, which he replaced by a solo practice of free short-term therapy, referrals, and advice to children and their families. Aichorn remained an ambiguous figure in the analytic community. Well-liked by both Sigmund and Anna Freud, he came from a conservative Catholic family allied to the Christian Social Party and would (and could) remain in Vienna through the war and beyond. Aichorn’s gift was his deep unyielding empathy for troubled children. He treated them with compassion and respect, and he was the most likely psychoanalyst to pull together the various schools of child psychotherapy. Upon his occasional absences his colleagues Editha Sterba and Willi Hoffer continued the Child Guidance Center’s work of evaluating and treating young school children referred by the welfare services. For most analysts dividing up the work day posed no problem, and many taught in the morning, analyzed patients in the afternoon, and in the evening attended seminars and clinical presentations at the Vereinigung. But best of all, the society really felt like a refuge. “The Berggasse is the center of everything,” Anna Freud observed, “and we revolve around it sometimes in smaller and sometimes in larger circles.”6

The Berggasse salon drew Siegfried Bernfeld for a brief visit to Vienna from Berlin in January. Bernfeld’s shock of dark hair and angular features enhanced an already powerful presence and his audiences were quite taken with his lectures on child neglect, adolescence, aggression, and sexuality. At one of the Vienna society’s winter seminar meetings, Edith Jackson, whose future in American child psychiatry would use Bernfeld’s theories to alter conventional medical care, found him “a marvelous speaker, clear, fluent, precise and picturesque with humour that bubbles up through the easy flow.”7 Neglect is not a simple concept, he insisted.8 A neglectful family’s sociological milieu, or environment, is so profoundly influential that two children who might start out with identical psychological dispositions are each affected very differently. At the end of the seminar two male teachers asked Bernfeld exactly how to respond when adolescent boys request advice on sex. Should they have intercourse or not? Do masturbation, abstinence, or early intercourse cause any permanent harm? In the developmental course of puberty, is there a normal sequence for erotic thoughts, masturbation, homosexual activity, and heterosexual activity? Bernfeld would not be lured into such banalities. The truth, he insisted, is that these generalizations are impossible because all human development is a joint product of the individual’s family history plus their socioeconomic status.

Bernfeld may have overemphasized the theme of individual aggression (or misread his audience) in his lectures on adolescence. Many Viennese analysts found it quite galling and dismissed it as the present thinking of the “Berlin School,” preferring Anna Freud’s current perspective. Between the late 1920s and 1936, when she would publish her classic book on The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense, Anna Freud reframed the role of the ego and granted it eminence in human psychological growth. She also insisted on respecting the psychological particulars of each developmental stage. In other words, a clinical technique that might help a six year old resolve his oedipal system would be inappropriate for an adolescent attempting to form an individual identity. Though Anna felt that Bernfeld’s tally of therapeutic successes was exaggerated, she generally agreed that his approach was interesting and clinically valid. “Fractionated analysis,” the unconventional treatment strategy adopted in Berlin, could be particularly effective with psychologically wounded adolescents.9 Nevertheless, during a case presentation at her own seminar one evening, Anna argued that Bernfeld’s treatment of aggressive adolescents like “Danny” was hindered because the analyst had disregarded the patient’s age-specific stage of development. A fifteen-year-old German boy, Danny coarsely berated his mother and blamed her for his gonorrhea (she “locked me up”) but also shielded her (“my fault for masturbating”), did well at school, and rejected psychoanalysis. What to do? Within a few minutes the seminar listeners had advanced a “fractionary” plan of gradually decreasing the analytic hours, systematically refraining from deep analysis, asking the patient for feedback, and inviting him to return should he feel depressed (an internal condition) or humiliated (an external condition).

Unlike Reich, Bernfeld rejected the idea of an overarching sexual narrative. No sexual action is universally harmful or helpful because each individual is a personal amalgam of early childhood history, individual personality, and social environment. Reich and Bernfeld also differed on their views of family life. Whereas Reich thought of the family as an insidious microcosm of patriarchy and bourgeois capitalism, Bernfeld was generally more forgiving. Several years earlier, Reich suggested to Freud that Sex-Pol would be “treating the family problem rigorously” in an immense campaign against moral hypocrisy. To this appealing but unlikely proposal, Freud replied, ‘You’ll be poking into a hornet’s nest.’” By 1932 Freud distinctly favored Bernfeld over Reich and was “always glad to see him. He [was] a brainy man,” Freud mused.10 “If there were a couple of dozen like him in analysis” he would worry less, and he hoped that Bernfeld, now in Berlin, would transfer back to Vienna for political reasons. Freud bluntly quipped that Hitler has made many promises, and the one he could probably keep is the suppression of the Jews. But, if Bernfeld realized the significance of Freud’s challenge at the time, he didn’t let on. He returned to Berlin and to his sympathetic group at the Socialist Physicians’ Union, which was, sadly, busier quarreling with other left-wing groups than planning a campaign against Hitler.

Soon after Bernfeld’s return to Berlin, the Socialist Physicians’ Union convened a meeting entitled “National Socialism: Enemy of Public Health.” Here Ernst Simmel offered the broad outlines of a Marxist solution to Germany’s worsening economic problems in combination with a psychoanalytic explication of Hitler’s Nazi activity.11 Overtly, Simmel seemed more interested in resolving the public health crisis than in alarming his audience, but he built his argument so strategically that, by the end, fascism and the quest for corporate medicine had become one. Formerly idealistic physicians, he thought, felt unable to spend enough time with their public patients, whose sheer numbers made for an assembly line practice, exactly the situation he had deliberately sought to avoid at the Poliklinik. This exploitation of the doctors represented, to him, the simultaneous rise of capitalism and of fascism. Simmel explained that the ruthlessness required for this kind of competition was so merciless that it undermined mutual human trust and ultimately led to war. A fascist government does the same thing: it replaces spontaneous individual human creativity with a totalitarian purview. In capitalism the corporation’s suppressed aggressive drives are released and, if unchecked, triumphantly acquire the rival’s private property and wealth or profits. In fascism the government unleashes its aggressive drives to gain property and power through war. In the end, both capitalism and fascism have war as a natural continuation of their goals. Hitler, he warned, was advancing on both fronts. Simmel’s argument was sophisticated and thoughtful for Berlin in 1932. Reading these passages from The Socialist Physician today, Simmel’s warning may seem obscured by the language of Marxism. Unfortunately, the rhetoric also hid the real value of his political insights exactly when Hitler’s weapons started to fire. The Nazis had become Germany’s largest elected political party, and Hitler had already put to use the vicious Sturmabteilung (SA, or brownshirted Stormtroopers) and the Stahlhelm (SS, or Steel Helmets) militia to support his case for seizing power.

Over the next few months Schloss Tegel, Ernst Simmel’s brilliant inpatient clinic that had always been more of a concept than a working reality, deteriorated so severely that staff realized it would not survive. “The experiment broke down,” Eva Rosenfeld remembered, “when parents and relatives of the patients wrote and declared themselves insolvent.”12 Families refused to take back their burdensome, mentally ill members who had finally, they thought, found appropriate caretakers. Some patients were discharged to institutions further away from the city, others to their own homes where they could live independently as cleaners and cooks. Those tasks accomplished, Eva stayed on to manage the termination and find jobs for the staff. Like her friend Anna Freud, Eva had never really thought this would happen. “Ever since I have known Tegel, the specter of dissolution has hovered over it. It was so beautiful and perfect in its principles and objectives,” Anna eulogized, “like a sort of dream; its insufficiencies and defects and the tight money situation didn’t seem to fit in but to be added on as if by accident. I always had the feeling that they might disappear and then Tegel would be what it can be.”13 But in the end the money simply ran out and not even Rosenfeld could be paid. Five years after Simmel officially closed down Tegel, Eva Rosenfeld found her life and livelihood at stake once again. “Having had vast experience in this type of work,” she wrote to Glover in London, “I would like to offer my services as supervisor and matron in hospitals (also organizing and training staff for mental hospitals). For more than ten years I was a supervisor in homes for drunkards and criminals and in Dr. Simmel’s Psychoanalytic Clinic, and I am sure I would always be able to do practical therapeutic and research work as a nurse.”14 Ultimately she returned to private practice in London and maintained an intermittent, if intense, relationship with Anna. What served Eva best for the next forty years was the superb analytic couch Ernst Freud had designed for her as a gift in Berlin of 1932.

Freud and Reich were wary of each other. In his diary entry dated Friday, January 1, 1932, Freud wrote, “Step against Reich.”15 He was responding to the controversy provoked by Reich’s proposed use of Marxist vocabulary in a 1931 psychoanalytic paper. Freud’s move was shaped by a range of possible factors. Either he was increasingly influenced by Jones and the more conservative members of the IPA or simply more wary of reactionary infringement than he had let on until now. Kurt von Schuschnigg had just been made minister of justice, a step aimed at helping Austria’s Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss repress the Social Democrats. The Nazi Party’s popularity was growing as fast in Austria as in Germany. Or perhaps Freud took this opportunity to act on Paul Federn’s suspicion of incipient schizophrenia in Reich. Whatever the explanation, Freud did indicate that overt left-wing political action could compromise the scientific credibility of psychoanalysis, already under attack from the medical, psychiatric, and academic establishments. Conversely, according to Helene Deutsch at least, Reich’s “political radicalism” was specifically not the cause of their estrangement; the problem, she thought, was Reich’s overbearing personality. In his theoretical work Freud broke with history; in practice he protected his discoveries. Freud and Reich were ideologically compatible on a metapolitical level—but certainly not without tension on the micro level.

Freud was not much happier with Franz Alexander, one of the earliest analysts to leave Germany for the United States. The first American outpatient psychoanalytic clinic was founded that fall in Chicago under Alexander’s direction. The clinic’s “basic purpose [was] the purpose of psychoanalysis everywhere,” he stated, “to make available the healing services of a group of specialists to those in need.”16 Alexander was a broad-shouldered and square-jawed man intent on disseminating psychoanalysis in America. Born in Hungary and trained as a physician, Alexander had worked first with Ferenczi and then, after a dozen productive years in Berlin, refused to yield anything to the Nazis. He agreed with his psychiatric mentor Emil Kraepelin (still alive and politically engaged in Germany) that sanatoriums should be established to treat “social diseases” like alcoholism, syphilis, and crime itself. Now in his mid-forties, Alexander adhered to the medical character of psychoanalysis and, he believed, its natural pairing with psychosomatic medicine. Although analysts could easily imagine which psychological symptom matched which physiological ailment, few had researched the actual forms a mental illness converted into. Franz Alexander called this “specificity” and hypothesized that specific linkages existed between damaged internal organs of the body and their corollary psychiatric disorders of the mind (liver and depression, spleen and anxiety). At first his controversial research attracted serious funding from prominent Chicago investors like Alfred K. Stern. To most analysts’ surprise, even the Rockefeller Foundation responded to Alexander’s proposal to fund empirical research on mind-body conjunction. Alexander could reconcile seemingly contradictory ideas, accepting at once the relational qualities of psychoanalysis and the biological nature of mental illness while persuading rich Americans of the scientific value of this inquiry. His colleagues were far more skeptical of the results. “The research does not amount to a row of peas,” the customarily uncritical Brill wrote to Ernest Jones.8 And when Alexander decided to help Karen Horney’s emigration by designating her as the new institute’s associate director, Brill fretted over the expense. Jones and Brill couldn’t believe that Alexander and Horney were charging fees for analysis when, specifically, “the Institute is not supposed to take any cases that can afford to pay regular fees.”9 Ironically, while this reproach came from the IPA’s two most candid opponents of free clinics, Alexander and Horney asserted their allegiance to the Berlin model. Their clinic was “the backbone of the Institute,” Alexander said, and they charged patients only “what they could afford. Some were treated for nothing.” On average, the 125 patients seen each year until the mid-1950s paid roughly $3 per hour. The Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis’s scientific meetings made ready use of the Poliklinik’s experimental techniques, and active therapy, conscious use of informality, and, most notably, treatment flexibility were practiced in the very first year. Like Richard Sterba reminiscing about the Vienna society, the American analyst Ralph Crowley remembered how “psychoanalysis was forward looking: it was a rebellion against old ways and old ideas…. The field was full of excitement and controversy…. Psychoanalysts were interesting people, devoted, not to achieving personal and financial security, but to experiment and exploration, and to the personal growth of themselves.”10 Unlike Sterba, however, there is little sense of a wider political endeavor. Perhaps this explains why none of the American psychoanalytic institutes, except for Chicago and Topeka, advanced free outpatient clinics. Until at least the mid-1950s the psychoanalytic societies in Boston, Detroit, Philadelphia, New York, Washington, Los Angeles, and San Francisco adopted training programs but, as Alexander commented in 1951, “they have restricted themselves primarily to theoretical instruction and clinical work with private patients.”11

Two of the other European clinics, London’s and Budapest’s, were planned with the same mix of voluntarism and financial support as the Ambulatorium. In London Pryns Hopkins’s Christmas donation included a hint that he would continue to support the clinic if he could. The clinic analysts, who did not contribute financially, agreed their work was both voluntary and separate from their teaching or administrative duties to the institute. These two decisions came from the board of the British society in its well-intentioned oversight of the clinic’s plans. In June, for example, the board agreed that one colleague’s role as translation editor for the IJP could exempt her from taking on clinic cases.12 In Budapest, meanwhile, the clinic was thriving. “We are positively overrun,” Ferenczi wrote to Freud, “and are striving to master the difficulties that are arising in this manner.”13 The difficulties were in large part financial, and, when Freud sent around a special petition to local society presidents appealing for support for the Verlag (the psychoanalytic publishing house), Ferenczi reluctantly reminded him that, at least in Budapest, any extra resources were directed to the clinic. Vilma Kovács, like himself, had already contributed fourteen hundred Hungarian pengö each year toward its maintenance.14 The other analysts earned barely what they needed to survive: they donated time but could hardly be expected to contribute cash.