2. COLONIAL 1715–1780

Emigrants to the New World, like their middle and lower class countrymen who stayed at home, neglected matters of style and fashion in favor of more elementary, practical, and traditional construction.

—Marshall B. Davidson, The American Heritage History of Notable American Houses, 1971

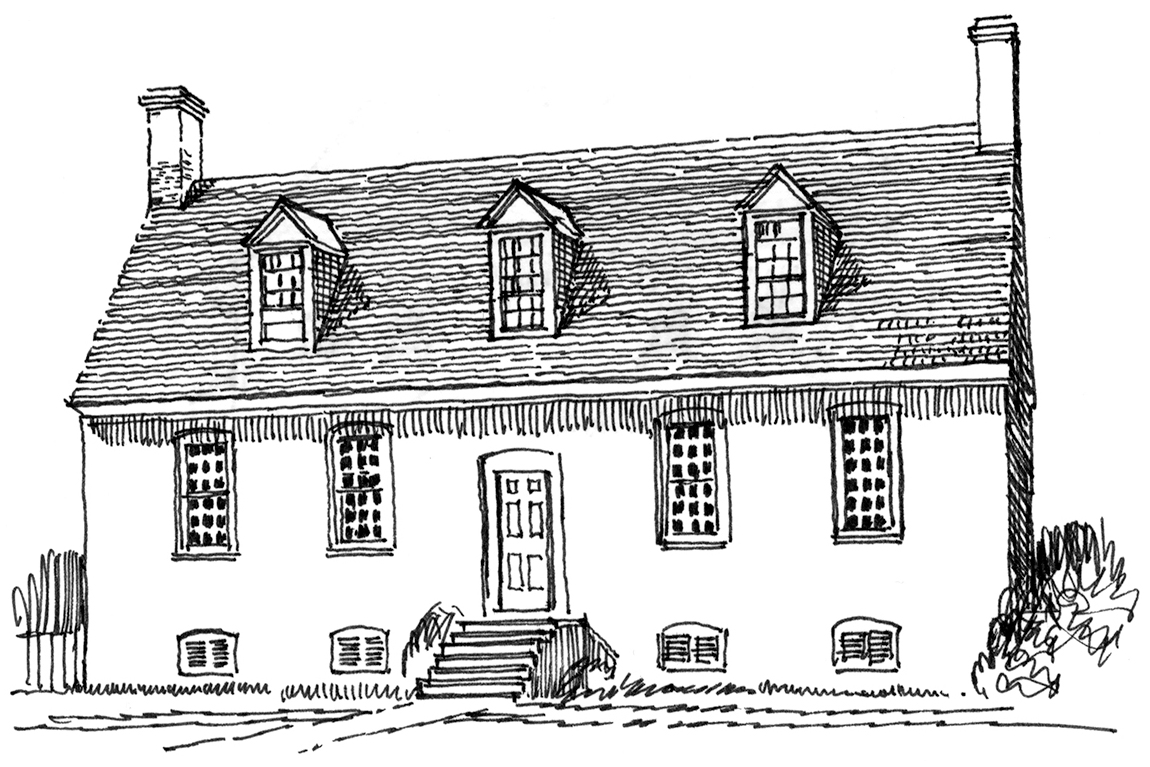

Toward the end of the seventeenth century many changes occurred in the appearance of our colonial houses. They no longer had an old-world medieval look. Double-hung windows (often called “sash windows”) had recently been introduced into England from Holland and soon found their way here. They were used almost exclusively by 1715. The panes were small, about 6 inches by 8 inches with 1-inch-thick muntins. Older houses were usually retrofitted with the new windows and the colonial house assumed a very different look from its earlier period.

Roofs became less steep—about 38 degrees instead of 50 degrees or more—and chimneys no longer had the clustered mass of their late-medieval prototypes. They were still large and centrally located in New England until well into the eighteenth century at which time the floor plan acquired a central hallway and chimneys were moved to either side of the house.

The original seventeenth-century rectangular “hall and parlor” layout was usually enlarged with the addition of a lean-to shed at the back creating the familiar saltbox shape. By the turn of the century saltboxes had become so standard that they were built with the long sloping roof as a deliberate element.

Typical Saltbox plan

Typical center hall Colonial

The equally familiar Cape Cod cottage evolved (not just on Cape Cod) as a one-story or one-and-a-half-story house. Originally these houses were built without dormers. Shingle siding was common, although clapboard siding continued to be used. Incidentally, these houses were rarely painted white before the nineteenth century when the Greek Revival craze swept the country.

What makes these houses Colonial, as opposed to Georgian, is their lack of fancy ornamentation. Embellishments of eaves, window heads, and door surrounds with even vestiges of classical details would make them Georgian or Georgian Colonial.

ENGLISH COLONIAL HOUSES

New England Saltbox

Cape Cod Cottage

Southern house

Double pile house—Two rooms deep on both floors

DUTCH COLONIAL HOUSES

Urban row house

Urban house

Rural farm house

New Netherland was founded in 1625. It extended from the Delaware River to what roughly corresponds to the New York/New England border. New Amsterdam and Fort Orange were renamed New York and Albany after the English seized the colony in 1664. (Although the Dutch regained New Netherland, they traded it for what is now Surinam in a 1674 treaty.)

The Dutch tradition placed the gabled end of their houses toward the street where it provided access to storage in the attic. Holland had no forests by the sixteenth century and brick was their principal building material. It was also used extensively in New Netherland. The bricks were often brought in ships’ holds as ballast. Windows were casements in the early houses, but double-hung sash windows became the norm after 1715. Parapeted brick gables were the standard for the attached urban row house. What has become identified as Dutch Colonial was supposedly derived from the Flemish farmhouse with its flared gambrel roof, but even this theory is open to debate.

The Dutch effectively won their independence from Spain by 1609 (the same year that Henry Hudson claimed the river that bears his name for the Dutch West India Company). Though nominally a monarchy, Holland was the first nation to be ruled by burghers in the form of the Estates General. Holland was essentially a mercantile country and trade was the source of wealth rather than the English notion of landed estates. They were a tolerant people and Holland became a refuge for Huguenots from France, Pilgrims from England, and Jews from Spain. The Dutch were never comfortable with the strict dictums of Renaissance architecture, which to them was associated with an authoritarian form of government and an aristocratic social order. Comfort, privacy, and a sense of domesticity were ideas developed by the Dutch in this era.* Dutch building had a great influence on English architecture in the early seventeenth century. Flemish or Dutch gables were popular Jacobean features in England, as were brick, double-hung sash windows, and solid shutters.

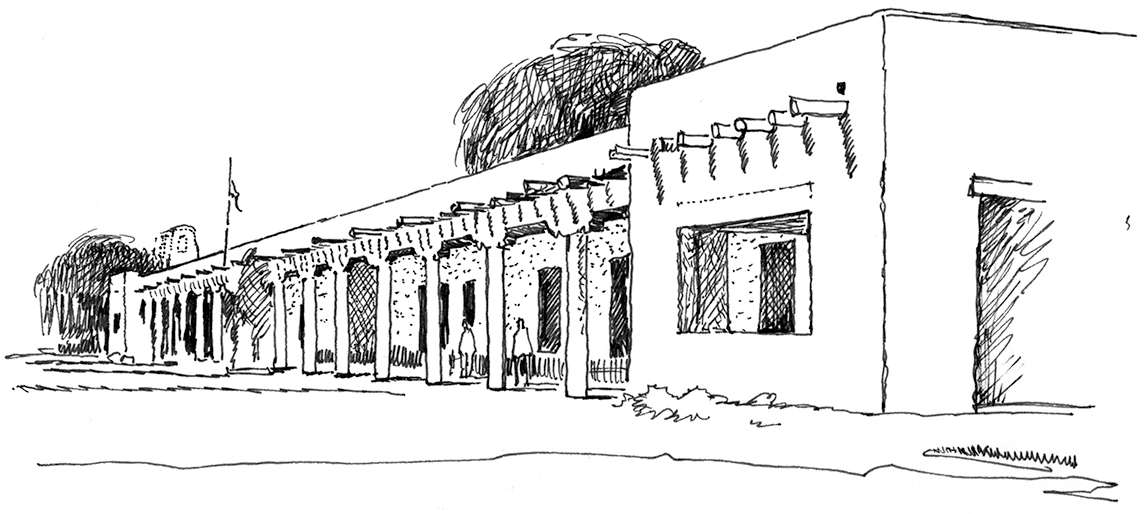

Spain came to the New World to find riches and to save souls. The Spanish had a mission of the sword as well as a mission of the cross. They founded missions throughout what is now our Southwest as well as Florida and California. Their churches were often elaborate architectural achievements, particularly in Texas and Arizona.

Ponce de León first attempted to found a colony in Florida at St. Augustine in 1513 but it failed. The colony founded at Tampa, however, succeeded in 1528. (This was one hundred years before the Massachusetts Bay Colony.) Missions proliferated throughout the Spanish territory during the eighteenth century. The architecture varied from crude huts to elaborate Baroque churches with intricate detail. The oldest house in America built by Europeans was the Governor’s Palace erected in Sante Fe, New Mexico, in 1609. It was the prototype for the Pueblo style (see pages 110–11). There are three other residential legacies from the Spanish era. The Spanish Mission churches inspired the Spanish Mission style (see pages 108–09), the one-story California ranchos built after 1821 sired our ranch houses (see page 112), and the blending of the New England colonial and the Spanish casa resulted in the Monterey style (see pages 114–15).

Governor’s Palace, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1609–1614

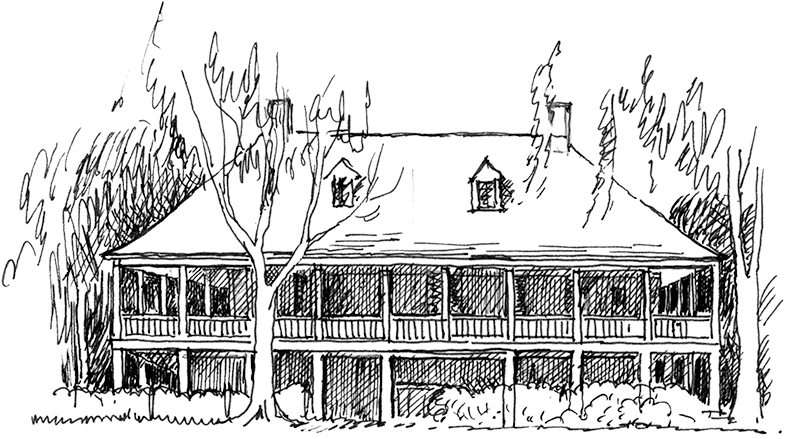

In the mid-eighteenth century the French colonial territory extended from the Alleghenies to the Rocky Mountains and from Labrador and Hudson’s Bay to the Gulf of Mexico. France controlled virtually all of the Great Lakes and the entire Mississippi River. Considering the size of the French domain, it is surprising that so little architecture of the colonial days has survived. The French built forts and trading posts but not new towns. There are no early surviving buildings in Detroit or St. Louis, and New Orleans was practically destroyed by fires before 1800. With the exception of the galleried plantation house, French colonial architecture had almost no impact on subsequent house styles. Remember that the British prevailed in the French and Indian Wars which ended in 1763, and Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase from the French in 1803.

Early seventeenth-century French-style houses were generally rectangular in plan and had no interior hallways. They had steeply pitched hip roofs. Sometimes a gallerie or veranda was included under the main roof or was sheltered by a roof with a shallower pitch. In damp locations the main floor was elevated several feet above grade. In the larger plantation houses in Louisiana this basement became an entire story and contained storage and utility space. Most of these survivors had French doors and galleries. The mid-nineteenth-century cast-iron balconies seen in New Orleans were chronologically Victorian and had no precedent in France. The gallery reappeared about 1830 as a feature of the Greek Revival house in the antebellum days of the “New South.”

Parlange, Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, 1750

* See Rybczynski, Witold, Home, A Short History of an Idea (New York: Viking, 1986).