9. REMINISCENT STYLES 1880–1940

Among wealthy women, the real tastemakers, gardening supplanted elaborate costumes and decoration as a mark of feminine gentility and culture.

—Mark Alan Hewitt, The Architect & the American Country House, 1990

Much of our architecture after the Civil War reflected the enormous success of American entrepreneurs. While the architectural excesses were exemplified by the apotheosis of the Queen Anne style—the Carson house in Eureka, California—and the palatial mansions of the Gilded Age, these excesses produced two basic responses. One was a search for the good life in a rural setting; the other was a step backwards into a simpler age for the character of American houses. The Arts and Crafts movement in England had its counterpart here in the Shingle style, the Prairie style, and the Craftsman style, all of which evolved as a reaction against the excessive eclecticism of the late nineteenth century. Whether the houses were of a formal traditional style or an interpretation of the more regional vernacular styles, the early decades of the twentieth century nurtured a new American way of living, much less formal than the English. There was a search for a comfortable rural life on farms—at least on weekends and during the summer months—where gardening and sports became a part of our lives.

In the period from 1910 to 1929—a time of prodigious house building—the Colonial Revival styles prevailed. The House and Garden movement flourished and the palatial palaces of the 1890s were viewed by most taste-makers as vulgar, pretentious, and ostentatious. The established class had money, leisure, and an interest in the good life. Life was less restricted—sports, riding, tennis, and golf included women—and houses became more a part of the landscape rather than an assertion of dominance over it. The Country Club founded in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1882 was the first of many golf and tennis clubs. Corinthian yacht clubs (where owners handled their own boats rather than having professional crews) sprang up along the Atlantic coast, and the Garden Club of America was founded in 1913.

House and Garden, Country Life in America, House Beautiful, The Craftsman, and the White Pine Series of Architectural Monographs were popular periodicals of the day. The White Pine Series sponsored a number of architectural competitions for house designs and the jury always included such distinguished residential architects as William Delano, Harrie Lindeberg, and Cass Gilbert. It is interesting, and I think revealing, to examine the attitudes of these juries around the time of the First World War. In praising the submissions in 1916, the jury admired “simple, direct, and logical solutions,” complimented “artistic skill” combined with “practical good sense,” and encouraged “fitness of purpose” and “direct sound construction.” “A good common sense livable house” should be “simple and dignified,” “simple” but “full of charm.” “A wise use of simple materials and simple forms is another sign of good taste which is rapidly coming into favor.” “The exterior is so quiet and so simple as to have the charm that goes with all restrained work.”

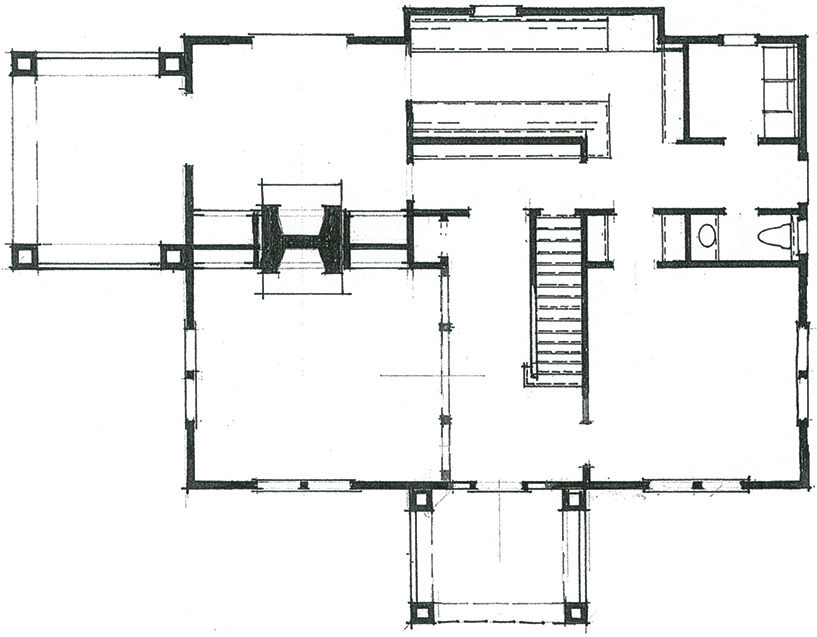

In commenting on American houses in 1918, the jury said, “we have completely avoided the pit falls of over-loaded ornament and the straining after something new, which has injured the architecture of both France and England and absolutely vulgarized any shred of good taste in Germany.” Though admittedly “doing the most restrained and most conservative work,” they emphasized that “if we do not want the architectural tree to die of dry-rot, we should welcome these alien grafts, however wild and wanton their growth or however strange their bloom.” In doing so they awarded fourth prize in 1918 for a vacation house to a Prairie style design cribbed from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Allen House, built in Wichita, Kansas, in 1917. (See the illustration on page 94.)

Mark Alan Hewitt, in his excellent book The Architect & the American Country House, said that it is time that these reminiscent houses “again be regarded as they were by the critics in their day, as key examples of a building type that contributed uniquely to modern American architecture.”* The architects of these houses found in simple regional architecture prototypes for the twentieth century. Even the rural vernacular styles of the English Cotswolds and countryside of Normandy were more comfortably at home on our shores than were Greek and Roman temples, Oriental harems, or spaceships from another galaxy. Why? Because they were of the land and were simple and direct vernacular solutions to similar kinds of architectural problems.

Good sound organization of space, an understanding of site planning, and “simple, direct, and logical solutions” are independent of style. The admonishments of the White Pine jurists are as appropriate today as they were one hundred years ago. It doesn’t mean that we must copy specific details or imitate historical styles, but there is much to be learned by studying the works of the architects who responded to the conservative domestic programs of their clients and found inspiration in the unpretentious and even modest rural structures both here and abroad.

Country Life in America first appeared in 1901 and continued as a popular magazine into World War II—its last issue was published in 1942. It stressed a theme of a genteel rural life.

The August 1925 issue featured The Arthur E. Newbold estate on Philadelphia’s “Main Line’’ by Mellor, Meigs & Howe, which epitomized the French Rural style—often called Manoir or Normandy Farmhouse.

EARLY COLONIAL REVIVAL 1885–1915

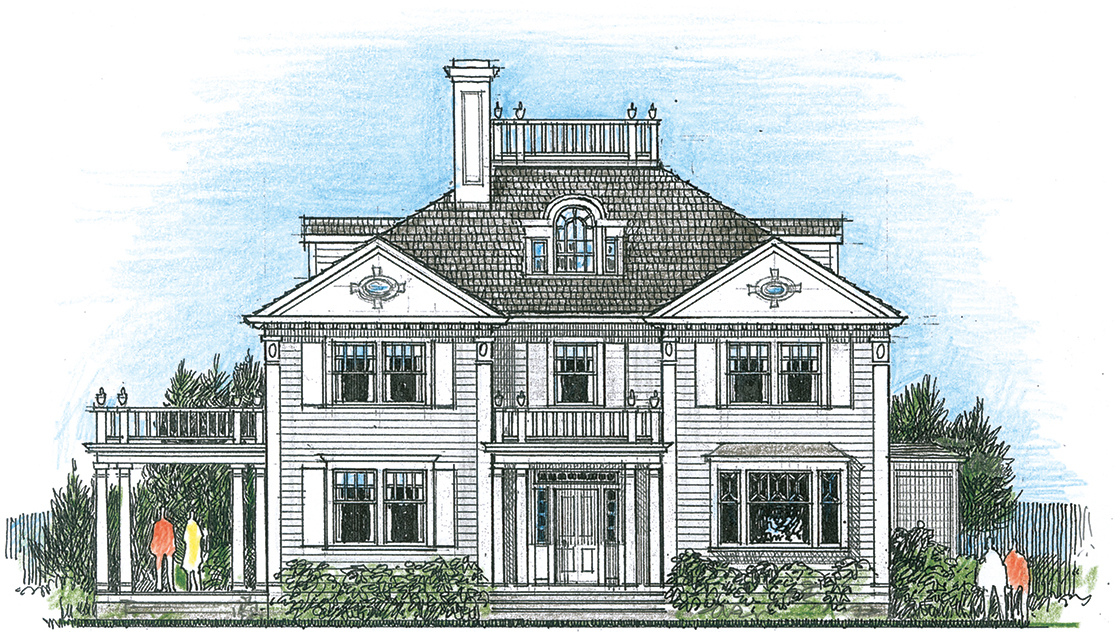

The centennial exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 stimulated a chauvinistic pride in our country. Though the Queen Anne style and the Shingle style both were popular in the 1880s, architects and pattern books encouraged a retrospective view of our late Georgian and Federal styles. These Neo-Georgian and Adamesque revivals were much larger buildings than their prototypes. Their designs were freely drawn from or inspired by their late eighteenth-century predecessors and were only reminiscent of the earlier styles. Windows were generally larger than in the originals and usually had divided lights only on the upper sash. No actual Colonial or Federal house ever used paired windows; their appearance is usually an instant clue to the age of the house. Great liberties were also taken with proportions and scale.

In 1877 Charles Follen McKim and his partner William Rutherford Mead made a “colonial” tour through New England with Stanford White who was soon to become their partner. They were looking for inspiration from our American architectural heritage. Their design for the Misses Appleton house in Lennox, Massachusetts, in 1883–1884 was perhaps the first major Colonial Revival house. The Taylor house, another early example of the style, was also built by them in Newport in 1885–1886.

The Early Colonial Revival borrowed eighteenth-century details and applied them to simplified Queen Anne houses. By the early 1900s, however, architects began to produce more “authentic” houses in the Colonial styles. Sometimes it is hard to tell the difference but for the predilection for paired windows and the ubiquitous side porch on Colonial Revival houses. The opening of restored Williamsburg in the 1930s gave a tremendous impetus to the revival of Southern Colonial styles and the “center hall colonial.” What real estate people call “colonial” is, for the most part, a style from the early nineteenth century. The ubiquitous, stark-white house with green or black louvered blinds was typical of the Greek Revival style and did not appear until the 1820s.

EARLY COLONIAL REVIVAL 1885–1915

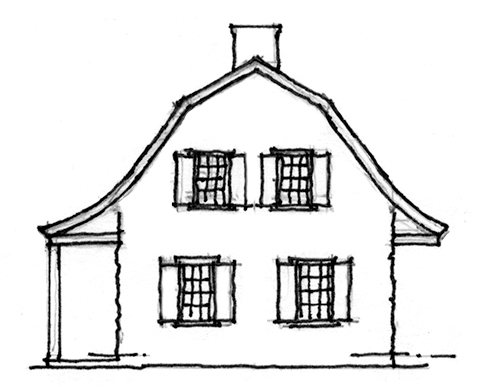

What is generally called Dutch Colonial is a house with a gambrel roof where one or both of the lower slopes flares at the eaves in a gentle curve. Though the gambrel roof was used in New England from the earliest days, the upper roof pitch is longer and steeper than the Dutch prototype. The Dutch made the lower portion of the roof longer and with a shallower pitch.

English

Dutch

With the possible exception of Dutch tiles around the fireplace openings, most details of the Dutch Colonial Revival follow the standard Colonial Revival patterns and are indistinguishable from them. Shutters with a decorative hole instead of louvered blinds were fairly common. The hole was apt to be cut in the shape of a half-moon, a pine tree, or a bell. Dormers either were separate roof structures or were a continuous element for nearly the full length of the building.

It is curious that the prototypes of the Dutch Colonial Revival were built throughout the Hudson River Valley and New Jersey but were not replicas of any house built in Holland. Scholars simply do not agree whether the characteristic roof of this Revival style was an adaptation of a Flemish farmhouse or was an original type developed here as an amalgamation of several colonial building patterns borrowed from the English.

Aymar Embury II (1880–1966) was a New York architect who did much to promote the style after 1910. He attempted to create a more “authentic” version of a colonial house than one would find in a Sears, Roebuck and Company or an Aladdin Redi-Cut catalog. The actual stepped-gabled, brick buildings of New Netherland were never revived in a twentieth-century adaptation of the style.

DUTCH COLONIAL 1890–1930

Next to Colonial Revival, the term Tudor is used to describe a greater range of house types than any other. In real-estate parlance, almost any front-gabled house with a steep roof and a large chimney is called Tudor. Elizabethan is used to describe half-timbered houses that derive more from the cottage or farmhouse than from the mansion.

The cross-gables, steeply pitched roofs, large chimney stacks with clustered flues or even spiral designs, all help identify the style. Tall windows with mullions and transoms framing casements with leaded glass are also typical features. The lower story is often brick and the floor framing of the second floor is projected out on the exterior a foot or so as it was in our early New England colonial houses. The two styles actually share the same architectural genes. The half-timbered effect—whether real or suggested by applied boards—confirms the style. Many Americans visited Stratford-upon-Avon and saw Anne Hathaway’s cottage which was the apotheosis of the Elizabethan cottage, complete with thatched roof.

The Elizabethan style became very popular after the First World War and continued to be built through the Depression years. Though it went into eclipse in the forties, it resurged in the seventies and eighties in a kind of pseudo-style. Called Neo-Tudor, its fake half-timbering is never convincing and has more of the quality of a stage set than a real house. I have never understood why anyone would want to live in a stage set.

Anne Hathaway’s Cottage

ELIZABETHAN 1910–1940

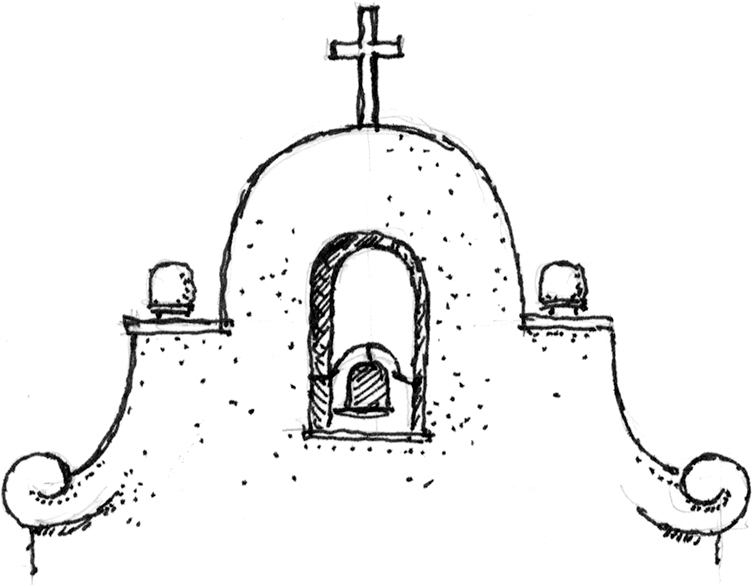

Just as the East was looking to its colonial past for architectural precedent and Colonial Revival work proliferated, the Southwest looked to the Spanish architecture of its colonial era for inspiration. The Spanish Mission churches with their Baroque parapeted gables and fanciful wall dormers were the impetus for the Mission style. The dominant curved parapet specifically identifies this style. Red tile roofs, projecting eaves with exposed rafter ends, and open porches with square or rectangular piers are all typical characteristics.

The Mission style started in California but soon spread when the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific Railroad adopted the style for their stations and resort hotels. It gradually spread east and crops up in surprising places. For example, the railway station and adjoining commercial buildings in Ridge-wood, New Jersey, are all Spanish Mission style with green tile roofs. After the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego in 1915, which featured the Spanish Colonial architecture, the Spanish Colonial Revival gained further impetus and the Spanish Mission style became simply one of many eclectic styles that derived from original Spanish colonial precedents.

It is important to note that the term Spanish Mission should not be confused with the mission furniture popularized by Gustave Stickley in his Craftsman magazine in the early 1900s. Mission furniture was an Arts and Crafts style promoted by artisans and manufacturers who “had a mission” to simplify and improve furniture design. Mission furniture might well be called “craftsman” as it complemented the architectural design of the Craftsman and Prairie styles.

Typical mission church c. 1700

SPANISH MISSION 1890–1920

J. C. Schweinfurth’s Hacienda del Pozo de Verona in Pleasanton, California, designed for Phoebe Apperson Hearst in 1898 was the first major residential commission designed in the Pueblo style. The single most important indicator of the style is the projection of roof beams a foot or so out from the adobe wall. They are called vigas. The prototype for the Pueblo style was the Governor’s Palace built in Sante Fe, New Mexico, in 1609 (see page 13). It was a blending of the local Indian building techniques with Spanish planning and details. A one-story adobe structure about 800 feet long, it had a covered porch, called a portales, extending almost the entire length of the building. The porch roof was a wood framework supported by wooden posts capped with bracket capitals (no arches, domes, or vaults). The patio side faces a lush garden—a Spanish contribution to this composite style.

Indian pueblos were multistoried structures made of sun-dried clay. The flat roofs were framed with straight poles. Smaller saplings were laid crosswise to the poles, and the entire framework of the roof encased in clay. If the vigas were prominent features so were the rainwater spouts, called canales, which also projected from the building and became another identifying feature. The Indians who inhabited these structures composed stable agricultural tribes who built pueblos as early as the ninth century. San Geronimo near Taos, New Mexico, was built about 1540. The Indians used the inner rooms to store supplies. Originally there were no doors at the lower level and people climbed ladders for access to the upper level. With the ladders removed, the buildings became effective forts with ample supplies to resist attacks.

The Pueblo style proliferated in the 1920s and 1930s and is still common in the Southwest. It seems a much more appropriate style than the pseudo-Mediterranean pallazzos that are promoted by many developers in that area.

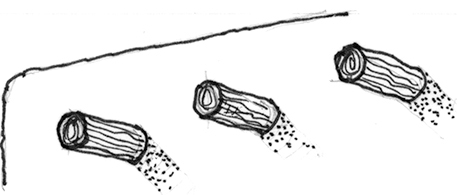

Vigas

Canales

PUEBLO 1900–l990s

SPANISH COLONIAL REVIVAL 1915–1940

The 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego was designed by Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue (1869–1924), an influential proponent of Spanish Colonial architecture adapted to the twentieth century. The climate and cultural heritage made the style eminently suited to the Southwest—California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and even Florida.

The red tile roofs, the simple forms subtly embellished at doorways, and the ornamental ironwork serving as protective barriers over windows were common details. The House and Garden movement in the East, which encouraged the concept of the house as a part of its own landscaped domain, had its counterpart in the Southwest. The simplicity of a Spanish courtyard with shade trees, hanging baskets, and flowering shrubs can hardly be surpassed.

Not all Spanish Colonial Revival houses managed to recreate the romantic character of a true hacienda. In too many instances suburban houses of no architectural distinction were identified as “Spanish” by the use of tile roofs, stucco walls, heavy wooden doors, and perhaps some ornamental ironwork. Very popular in the 1920s and 1930s, the style’s popularity declined after the Second World War.

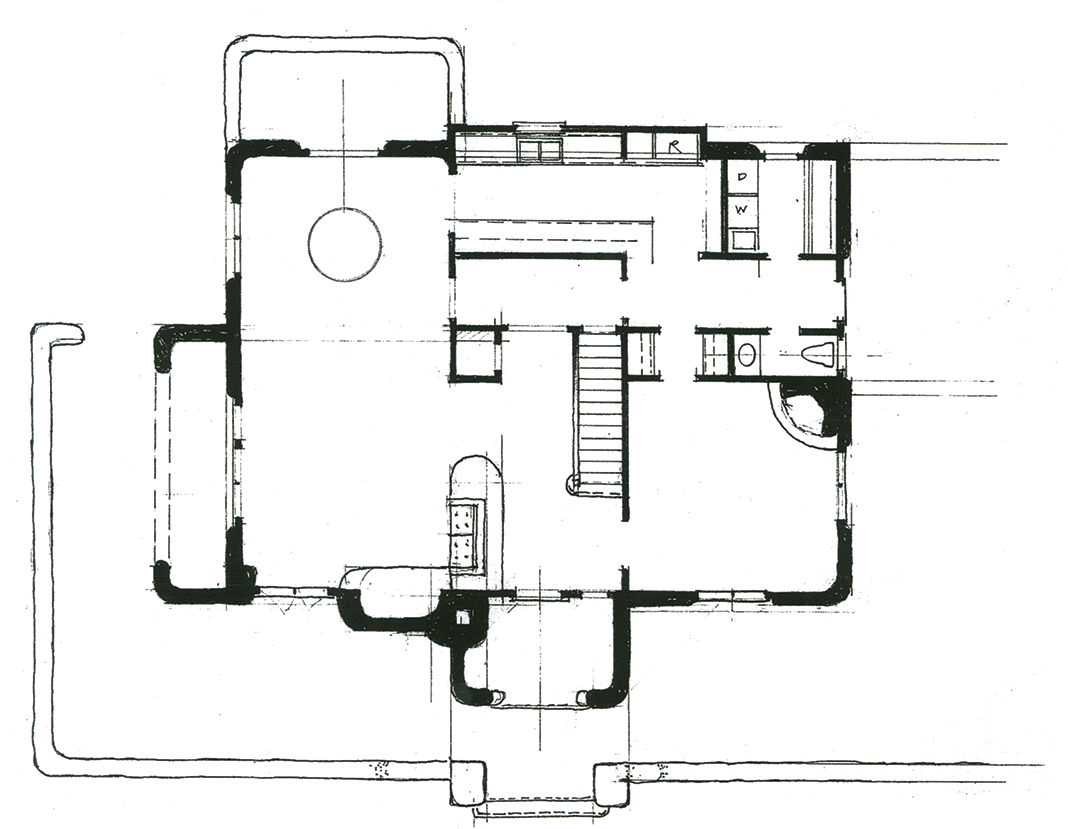

The most lasting legacy of the Spanish Colonial Revival as a national type was the one-story house which we know as the ranch house. Its characteristic U-shaped floor plan with a protected patio in the courtyard derives from the California ranchos of the 1830s.

Ranch house c. 1835

SPANISH COLONIAL REVIVAL 1915–1940

More than ten years before gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, California, Yankee merchants were sailing around Cape Horn and trading with the Spanish along the southern Pacific coast. In 1821 the Mexican government started granting huge tracts of land to Spanish entrepreneurs to encourage private ranching. The 1830s and 1840s was a prosperous era and there was a lively trade in hides and tallow. Monterey, Santa Barbara, and San Diego became important ports (San Francisco not until 1849).

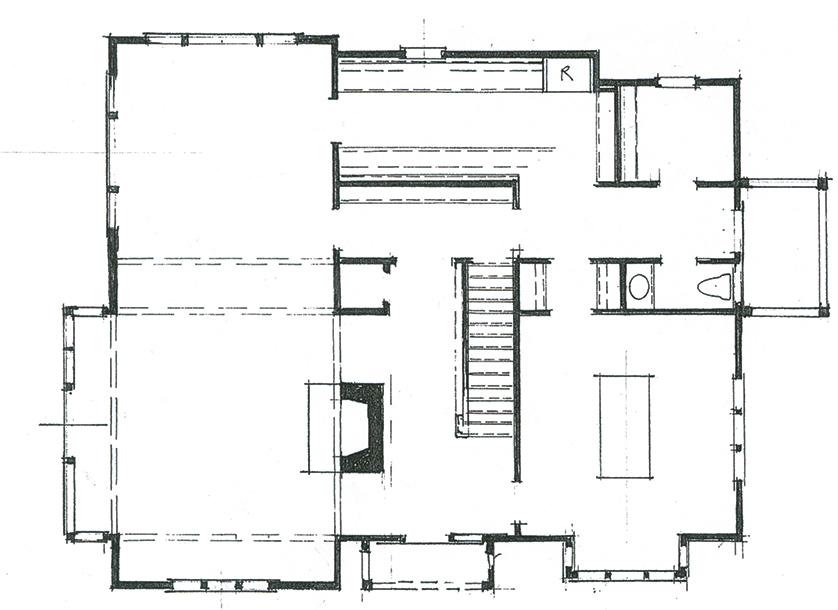

Thomas Larkin, a Boston merchant, built a house for himself in Monterey in 1837 which blended the basic two-story New England colonial house with Spanish adobe construction. Virtually all previous Spanish colonial houses were one story. This innovation combined with double-height roofed corredors (porches) around the structure to create a new style. The gently sloped roof was often covered with wood shingles instead of tile and served to protect the adobe walls—another innovation in the Spanish territory.

Interior fireplaces, kitchens, and glazed windows were all new features in the California landscape. Though redwood was available for house construction, people continued to build with adobe. They found that it was much cooler during the summer, and in the colder months the thick walls absorbed heat during the day and slowly radiated it during the night. This was the most fundamental principle of passive solar heating at work.

In the 1920s the compulsive search for colonial precedent led to a revival of the Monterey style. Interpretations of the Monterey style house can now be found in every part of the country.

Thomas Larkin House, Monterey, California, 1837

MONTEREY 1925–1955

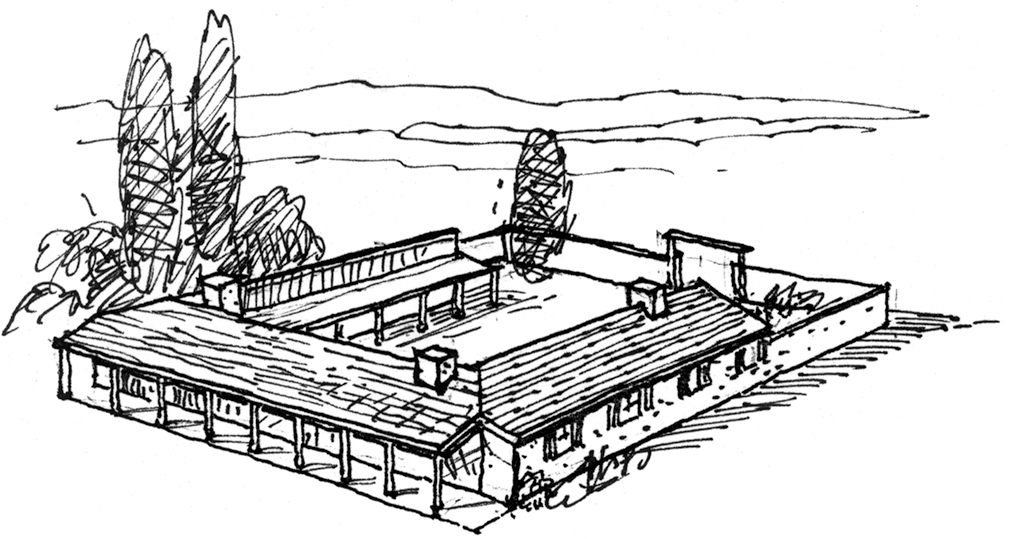

Americans who studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in the nineteenth century studied classical architecture—particularly the grandiose classicism associated with the school. As the revival styles caught on here prior to the First World War, the rural vernacular architecture of the French countryside became an important inspiration for our residential architecture. The steeply pitched hip roof with subtly flared curves at the eaves, the circular stair towers, and the substantial but uncoursed stonework had tremendous appeal to Americans. Many of our soldiers came back from the war with an appreciation of the rural beauty of France. Young artists, writers, and architects went to France in the twenties and our love affair with France continued. H. D. Eberlein’s Small Manor Houses and Farmsteads in France published in 1926 and Samuel Chamberlain’s Domestic Architecture of Rural France in 1928 were popular resources for residential architects.

Philadelphia was particularly receptive to these rural French houses. Normandy Village in Chestnut Hill and the work of Mellor, Meigs & Howe on the Main Line were particularly important. Arthur Meig’s idyllic farm complex for Arthur E. Newbold, Jr., in Laverock appeared on the cover of Country Life in America in 1925 and captured the essence of the movement (see page 101).

In our desire to identify house styles with a particular time and place which we feel express feelings about ourselves, we use names like “Normandy farmhouse,” “French Provincial” (although that term has come to imply something pretty vulgar in recent years) or, for the anglophile, the “Cotswold cottage.” One or two small details can suggest one style over another when in fact the basic houses are quite similar. All are basically forms of a comfortable country style.

FRENCH RURAL 1915–1940

* Hewitt, Mark Alan, The Architect & the American Country House (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990).