3. GEORGIAN 1715–1780

. . . the Georgian, with its formal symmetry and finer materials and delicately executed ornament, was the expression of a wealthy and polite society.

—Hugh Morrison, Early American Architecture, 1952

When the Great Fire of London consumed the city in 1666, Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723) was the architect chosen to rebuild it. The conflagration virtually put an end to the medieval city, and the classical forms of the Renaissance predominated in its reconstruction.

With the restoration of Charles II to the English throne in 1660 the Renaissance style flourished. The houses built in this era were generally restrained, dignified, and refined classical buildings which served as the prototypes for the best of the Georgian architecture in the American colonies.

Queen Anne was the last of the Stuart monarchs. She died in 1714 and was succeeded by George I—the beginning of the Georgian era. With the exception of a few lavish Baroque essays built during her reign, like Sir John Vanbrugh’s Blenheim Palace and Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Castle Howard, most Queen Anne houses were relatively modest. It was the character of these late Stuart houses that set the tone of the American Colonial Georgian period.

Throughout our Colonial Georgian era, very little of the actual English Georgian architecture even reached North America until after the Revolution. Our Federal and Neoclassical architecture then borrowed from the English Georgian styles of the mid-eighteenth century.

Two important influences shaped the character of English residential architecture of our Georgian period. One was the Dutch architecture of the late seventeenth century with its use of brick and contrasting sandstone, hipped roofs, and domestic scale. The other was the Palladian movement. Renaissance classicism bloomed under Wren but the self-conscious and rigid Palladianism evolved during the reign of George I. The English translation of Andrea Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture and the first part of Colen Campbell’s Vitruvius Britannicus, an elaborate treatise with Palladian designs recommended for Britain, were published in 1715. Both books had a formidable influence on residential architecture.

STUART ARCHITECTURE

Queen’s House, Greenwich, England, by Inigo Jones, begun 1617

Squerryes Court, Westerham, Kent, c. 1680

Mompesson House, Salisbury, Wiltshire, 1701

Belton House, near Grantham, Lincolnshire, 1684–1688

To understand Georgian architecture one must know something about Andrea Palladio (1518–1580), who was one of the most influential architects of all time. A native of Vicenza, his country houses inland from Venice were unlike anything that had been built before. They inspired generations of architects, dilettantes, and scholars.

His innovations became gospel for British architects from Inigo Jones and Sir Christopher Wren in the seventeenth century throughout the Georgian era of the eighteenth century. His influence was felt in the American colonies and is still in evidence today even if in vestigial form.

AMERICAN GEORGIAN

American Georgian houses built after 1715 were based on the Stuart architecture of late seventeenth-century England.

Westover, near Charles City, Virginia, 1734

Hunter House, Newport, Rhode Island, c. 1746

Wentworth-Gardner House, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1760

Corbit House, Odessa, Delaware, 1772–1774

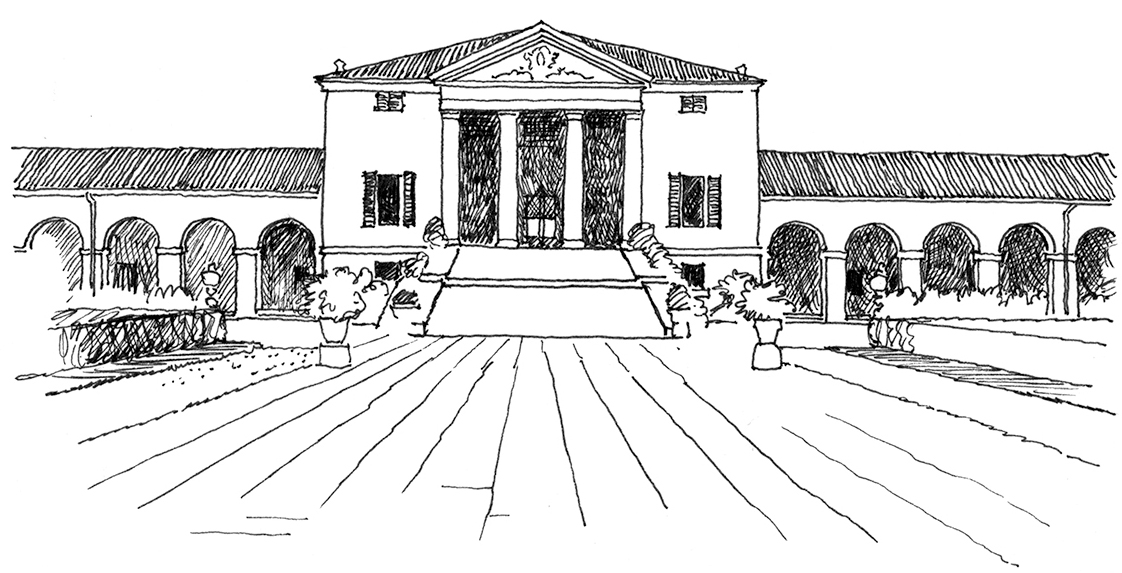

A House at Cefalto for “The Magnificent Signor Marco Zena” from Palladio’s Second Book Plate XXXII

Tulip Hill, Anne Arundel County, Maryland, 1745–c. 1785

By the mid-sixteenth century, Venice had become an immensely wealthy independent city-state. The new humanistic doctrine fostered an intellectual community with a cultured upper class that was distinctly separate from Rome. The Venetians even developed an empathy with the Protestantism that was emerging in northern Europe. It was in this milieu that Palladio found an outlet for his talents.

What was so special about Palladio and why was he different from other Renaissance architects? The inventor of a new kind of country house—one that became the prototype for the eighteenth-century English estates and the plantation houses of the American South—he codified a personal adaptation of the ancient classical orders and developed a system of harmonic proportions for his spaces. His sophisticated farmhouses for an educated agrarian class were rural structures that incorporated the functional components of a working farm into ordered and controlled compositions. Even the attic space of many of his houses was used to store hay! The now-familiar five-part composition—central block with symmetrical dependencies connected by hyphens—was Palladio’s innovation and was one attribute of his work that was widely imitated by his followers.

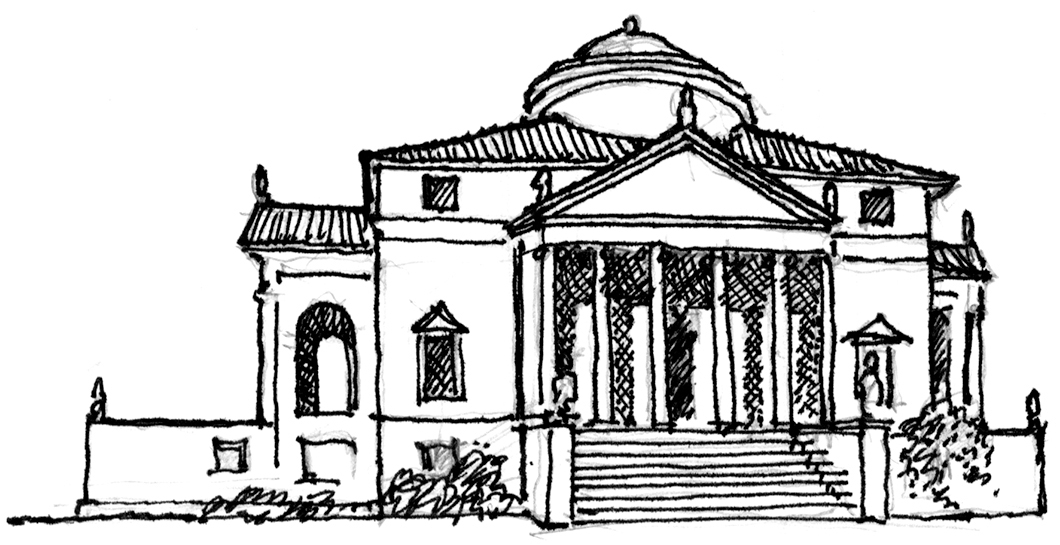

The other two principal features that characterize Palladio’s work were his use of the central pedimented portico to emphasize the importance of the entrance facade and the reintroduction of the dome in a domestic building. Both features had long been associated with religious buildings and were as strange as a church steeple would be on a suburban house today. He incorporated these elements into his designs to infuse his houses with a sense of “grandeur” and “magnificence” (two of his favorite words). He felt obliged to justify the use of both the pediment and the dome by explaining in his Four Books of Architecture that they were originally derived from domestic structures (hence the word domus) and were therefore a legitimate use of the forms.

Palladio also used a mundane finish material on these grand houses: plain stucco or plaster instead of cut stone. The plain surfaces were painted warm earthy tones which infused them with a richness of light and color that was more akin to the vernacular architecture of Italy than to the pallazzos of Rome and Florence. These were inexpensive materials, and their simplicity was a subtle counterpoint to the richness of his details.

It is interesting that a handful of country villa/farmhouses and a single anomalous belvedere, the Villa Capra (Villa Rotonda) near Venice, would launch Palladio’s name into western residential architecture. His word was spread with almost evangelical flame by his English proponents in the eighteenth century. Many of his admirers had traveled to Italy and seen his work. His four-volume treatise on architecture included many of his own designs as well as measured drawings of ancient Roman buildings. As a writer he was a first-rate public relations expert and it was his books, as much as his actual buildings, that lead to his great renown. Lord Burlington (1694–1753) was his single most important promoter in Britain in concert with Colen Campbell (d. 1729). Both built houses based on the Villa Rotonda.

Villa Emo, Fanzolo, Italy, by Palladio, 1559

Villa Capra (Villa Rotonda), Vicenza, Italy, by Palladio, 1556–1570

Mereworth Castle, Kent, by Colen Campbell, 1723

Chiswick, Lord Burlington’s House, Middlesex, 1720s

Before examining the various styles that derive from classical prototypes, I want to focus on one detail that is often constructed incorrectly—always to the detriment of classical design. The difference is not generally understood or appreciated.

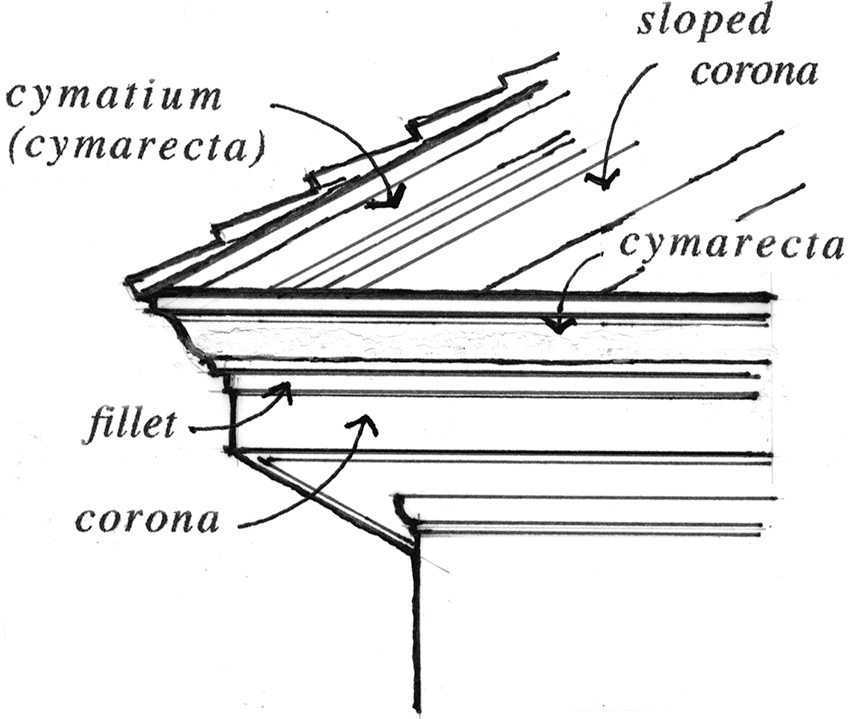

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries there were pattern books that provided builders with classical details based on accurate, measured drawings of actual classical buildings. The two drawings below show the right and the wrong way to construct the cornice. If one is going to use the details, it might as well be done correctly. Asher Benjamin stated, though admittedly not all that clearly, in his 1827 edition of The American Builder’s Companion, “It is to be observed, that the cymarecta and fillet above it, of the cornice, are always omitted in the horizontal one of the pediment; that part of the profile being directed upward to finish the inclined cornices.” Though somewhat verbose, the author is specific in his instruction that the S-shaped crown molding, the cymarecta, caps the top of the pediment and is not returned on the horizontal corona.

CORNICE DETAILS

RIGHT

This is the only place the crown molding should be positioned. Note that the crown molding—the cymarecta—follows up the rake above the upper part of the “split” or “hinged” fillet and not on the lower part just above the horizontal corona.

WRONG

Though you often you see this detail, it is flat and uninteresting when compared to the correct classical standard. It places the emphasis on the horizontal portion of the pediment rather than on the rake.

CLASSICAL ORDERS

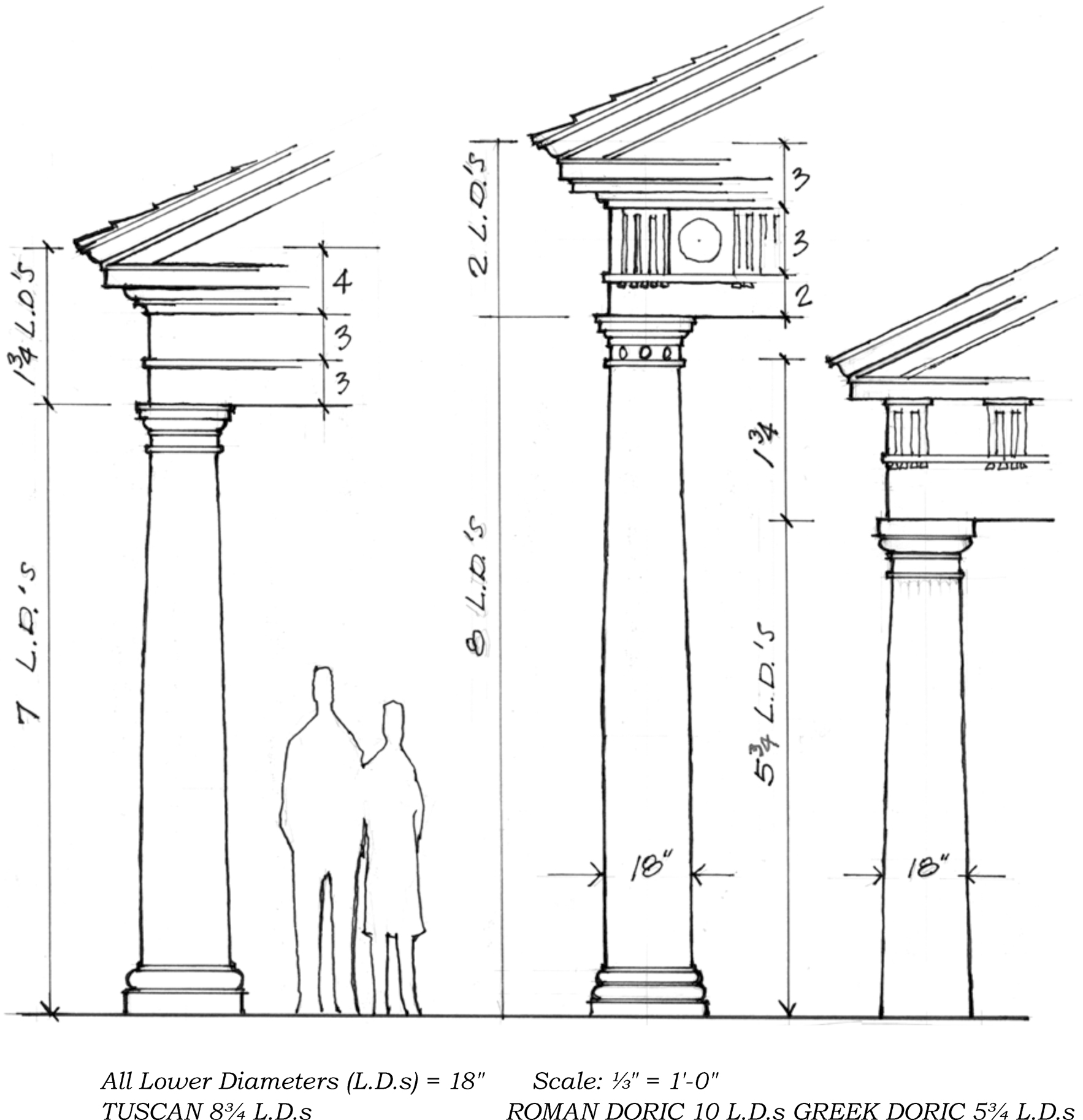

There are five Renaissance orders. The Composite order, however, is extremely rare and is quite similar in proportion and scale to the Corinthian.

The component parts of the classical orders are all proportioned to the diameter of the lower part of the column. Columns curve inward for the upper two-thirds of their height. (All the orders shown here have the same lower diameter of 18 inches.)

The columns vary from seven to ten L.D.s in height. The entablatures are one-quarter the height of the column, and the divisions of the architrave, frieze, and cornice are governed by strict rules. The Greek Doric order was 7½ L.D.s and the column only 5¾ and had no base.

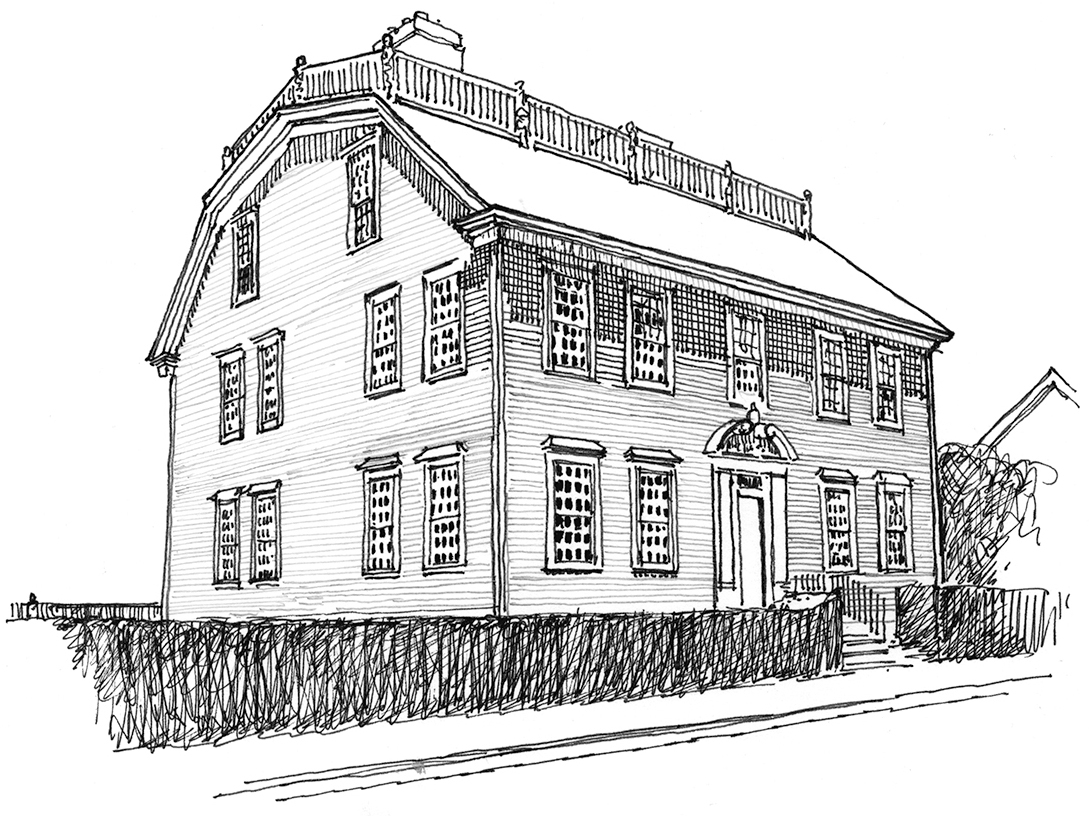

GEORGIAN—New England 1715–1780

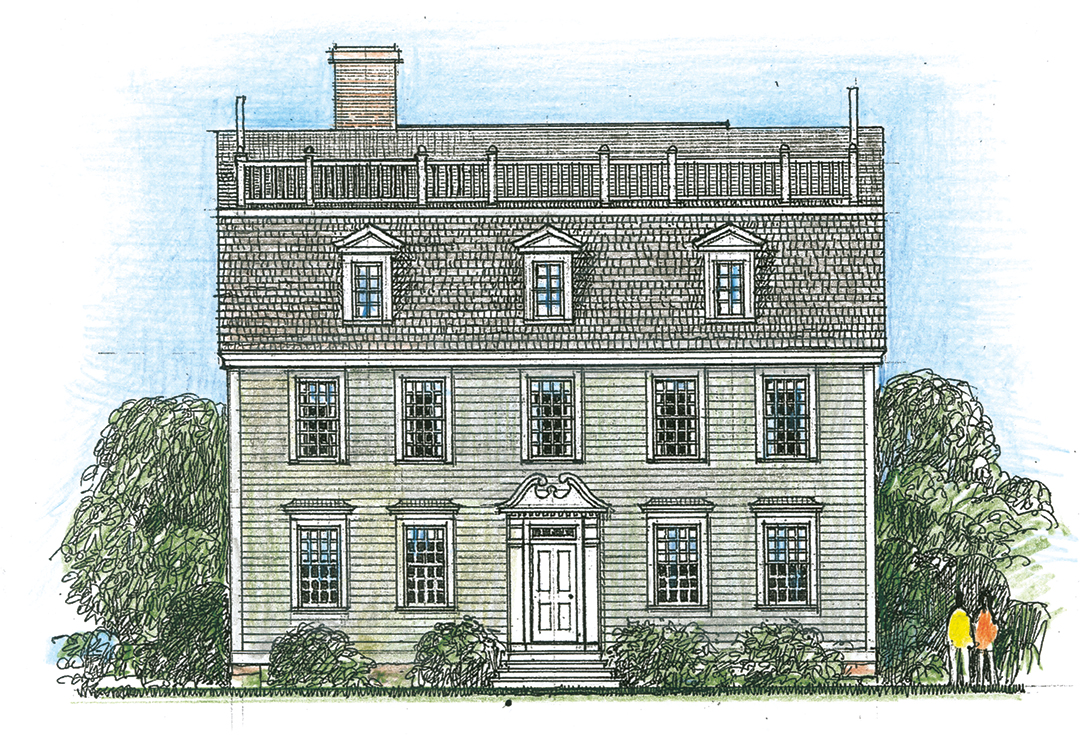

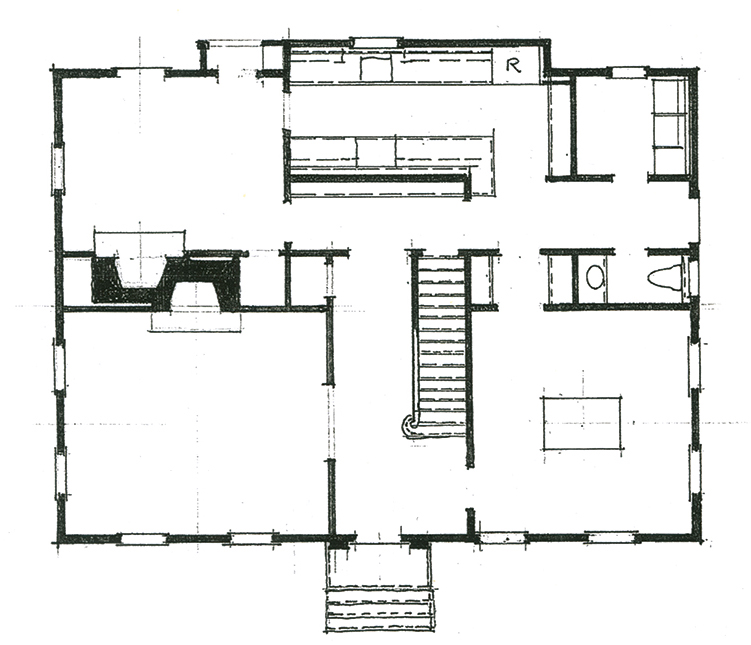

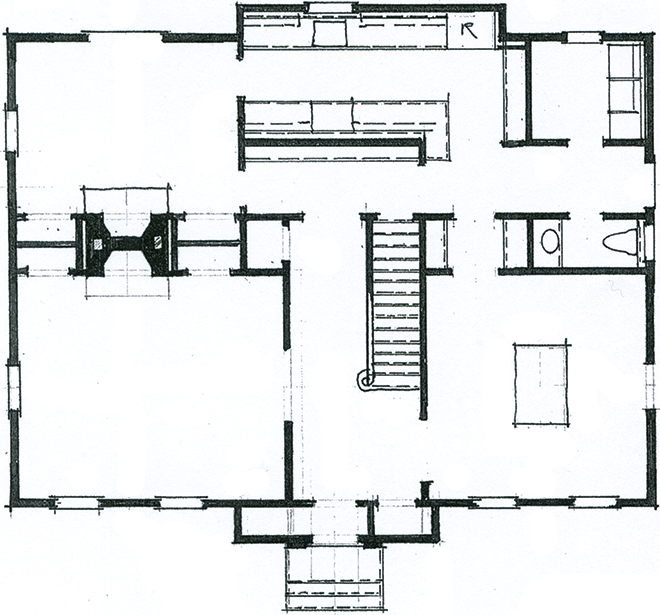

Whether built in the North, the South, or the Middle Atlantic colonies of Delaware, Pennsylvania, or New York, the same simple formality epitomized this new popular style. Symmetry, aligned windows, and accepted conventions based on Renaissance precedent for all the basic component parts of the house characterize the American Georgian style. The proliferation of English pattern books served to ensure a unanimity or consistency of design throughout the colonies. There were regional differences based on available materials, cultural patterns, and social attitudes, but the variations were all on a basic theme.

Roofs were either gambrel, gabled, or hipped. The gambrel was much more common in New England than in the other regions. The illustration shows the gambrel roof on a house one could find in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Newport, Rhode Island, or up the Connecticut River Valley.

The New England Georgian house of the mid-eighteenth century usually had a distinctive paneled door accentuated by classical pilasters and capped by a well-proportioned, pedimented entablature. A transom light, either rectangular or half-round, was common, but neither side lights nor elliptical fanlights appeared until after the Revolution.

Windows were surrounded by molded architraves and capped with classical crown moldings or cornices. The eaves, by definition, had classical cornices often with modillions on the soffits. The upper windows were usually set just below the eaves and were the same size as the lower windows. Divided lights were set in 1-inch-thick muntins and were 6 inches by 8 inches or 8 inches by 10 inches at the largest. Glass was still imported and still very dear. After 1750 the balustrade was introduced and was generally set high on the roof. Neither louvered blinds nor shutters were a feature of the New England Georgian house. Louvered blinds were introduced late in the eighteenth century and probably came from the South.

Georgian houses generally did not have covered porches at the front door. There might be pilasters framing the doorway with an entablature above projecting a few inches from the face of the wall, but no roof supported by columns. Whenever an entry porch appears on a Georgian house it was probably added after the Revolutionary War.

GEORGIAN—New England 1715–1780

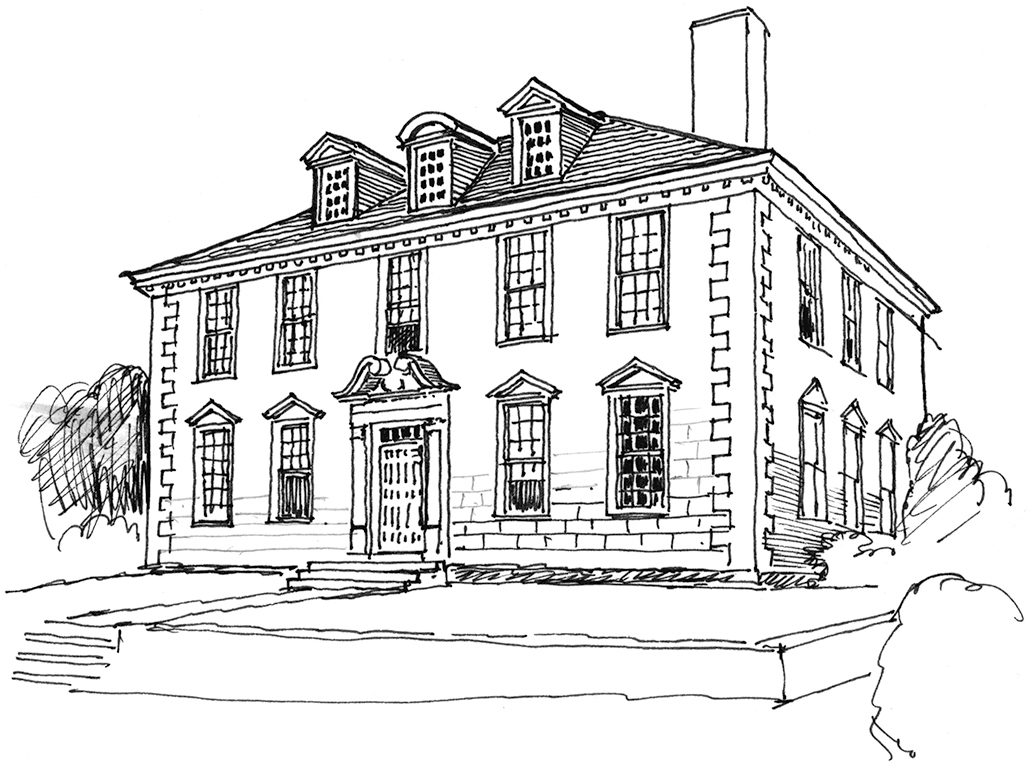

GEORGIAN—The Middle Atlantic 1715–1780

Stone was the most common building material in Pennsylvania and the Delaware Valley. Unlike New England, lime was readily available and the settlers—who came mostly from the midlands of England—were accustomed to masonry construction. Philadelphia was by far the largest city in the colonies at that time and certainly had the finest architecture. Though he never actually settled there himself, William Penn brought architect/builders with him to his new colony. Most of the settlers were Quakers and came from the Penine moorlands.

Somewhat heavier moldings and details were seen on these buildings than in the other colonies—perhaps to reflect the more massive quality of the stone. The fully pedimented gable with its horizontal corona returned across the gabled ends. The cornice was often highly decorated with modillions and dentil work.

Though paneled shutters were introduced in the colonial period, louvered blinds came in quite late and were often seen just on the upper floor. Even today around Philadelphia you will see white shutters on the lower story and dark-green louvered blinds above.

A distinctive feature of the Pennsylvania house was the “pent”—an appended roof that was secured or hung from the wall above without brackets or posts to support it. Called a “pentice” in England, it was common in the midlands. Sometimes the pent extended all the way across the face of the building and, as shown in the illustration below, occasionally with a pedimented portion that emphasized the front doors and diverted the rain from the porch below.

The double-hung windows, typical of all Colonial Georgian houses, tended to be “6 over 6” (that is, 6 panes in the upper sash and 6 panes below), 6 over 9, or 9 over 12 with 1-inch-thick muntins. Generally the glass size was still fairly small—6 inches by 8 inches or only slightly larger.

House with pent

GEORGIAN—The Middle Atlantic 1715–1780

Brick was by far the most common building material in the southern colonies for large houses, usually laid in Flemish bond (alternating headers and stretchers). The hip roof, while sometimes used further north, predominated in the southern colonies. The influence of the restrained late-Stuart style of residential architecture was at its peak in the plantation houses of the Virginia tidewater prior to the Revolution.

As in the English prototype, window panes were small, the muntins at least 1-inch thick, and the exterior casings rather narrow. The major decorative elements were featured at the eaves in the form of classical cornice detail often enriched with modillions and occasionally a pedimented doorway with a well-proportioned transom light. Semi-circular transoms were common as were rectangular ones. Remember that sidelights and elliptical fanlights were not used in any of the colonies until after the Revolution. The Brewton House in Charleston, South Carolina, built between 1765 and 1769, is “the only undoubtedly authentic example of this motive in a pre-Revolutionary house.”*

The best examples of the style can be seen in Virginia. The Wythe House at Williamsburg (1755) is an excellent example. Also Stratford, Carter’s Grove, and Westover, all built between 1725 and 1753. Mount Airy, finished in 1762, was copied from English architect James Gibbs’s Book of Architecture and is pure Palladian.

Although most southern Colonial Georgian houses were brick, Mount Vernon is the most notable exception. It was timber-frame with wooden siding. But even there, when Washington remodeled the house in 1757, he not only simulated masonry by incising the boards to look like stone blocks, but he actually textured the siding with a paint mixed with sand (see page 34).

Mount Airy, Warsaw, Virginia, c. 1762

GEORGIAN—The South 1715–1780

* Morrison, Hugh, Early American Architecture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1952; Dover, 1987), p. 416.