4. THE YOUNG REPUBLIC 1780–1820

More so than ever in the colonial period, buildings were now not only frameworks in which to live and work; they were also provocative projections of what Americans wanted to be.

—David P. Handlin, American Architecture, 1985

The Treaty of Paris in 1783, seven years after our Declaration of Independence, confirmed our nationhood but not our sense of nationality. There were too many disparate forces to be merged to expect a spontaneous social order that encompassed all our differences. Benjamin Franklin admonished at the time, “Say, rather, the War of the Revolution. The War of Independence is yet to be fought.” Democracy was still a dubious and volatile experiment.

There was no White House and no capitol dome to symbolize our unity. Philadelphia, not Washington, was the nation’s capital for over ten years. After a brief time in New York, the capital was located in Philadelphia from 1790 until 1801. William Penn’s Quaker town had grown to be the largest city in the confederation—over 70,000 inhabitants and, next to London, the largest English-speaking city in the world. New York trailed by 10,000 and Boston had a mere 25,000 inhabitants. Strongly Tory during the Revolution, Philadelphia remained a patrician city and still felt comfortable with the late Georgian architecture of the mother country as did Boston, Newport, Salem, Charleston, and most other centers of commerce.

Not every colonist supported the Revolution—perhaps as many as a third of the population were loyalists even as late as 1800. When war broke out between England and France in 1793 there was a strong British sentiment among the Federalists. Jefferson’s Republicans, more like the Democratic party of today, favored France. George Washington warned against our involvement in the quarrels of foreign nations in his farewell address in 1796. Our failure to heed his sagacious advice did much to polarize society in the years that followed, in a time when the former colonies needed cohesion.

This was also a time of financial crisis. The federal debt in 1790 was $54,000,000. On the other hand the government owned enormous amounts of land confiscated from the British Crown as well as individual loyalists’ holdings. This land was made available to an increasing number of freeholders both in the former colonies and in the hinterland. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 affirmed the equality of new states entering the union and was a great incentive to settlers who could move to the frontier with confidence that their rights would be protected. New states soon followed the original thirteen: Vermont in 1791, Kentucky in 1792, and Tennessee in 1796 were formed from federally owned territories or those sections where all disputed claims were withdrawn by the former colonies.

After the War of 1812, which Franklin might well have considered the real “War of Independence,” America was well on its way to becoming a self-sustaining nation. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 nurtured the shared ideal of a manifest destiny so much a part of our national psyche by mid-century. What about our architecture?

In the years before our independence the character of English Georgian architecture had begun to change. Archaeological discoveries at Herculaneum in 1719 and Pompeii in 1748 showed that the classical orders had much greater variety than Palladio or Vignola, another important architect who codified the classical orders, reported in the sixteenth century or than Vitruvius recorded in classical Rome. The Neoclassicism that was spurred by Thomas Jefferson drew not just from Palladio but also from the influential book Antiquities of Athens by Nicholas Revett and James Stuart, published in England in 1762. It is hard for us today to imagine that the use of one Ionic capital instead of another would be considered revolutionary. In fact, to a rigid Palladian, it was an extremely bold and unorthodox step.

This classicism of the early nineteenth century is often called Adamesque or the Adam style after Robert Adam (1728–1792) and his brothers who developed the style. They enjoyed the largest and most successful architectural practice in Britain from 1760 to 1780. With offices in London and Edinburgh, they were also developers in the way we use the term today. Although they drew from Palladio’s work in their early years, their later work demonstrated a freer interpretation of the classical orders, extensive use of decorative panels, and, by American standards of the day, an excessively gaudy use of color and gilt in their interiors.

Typical Federal and Adam details

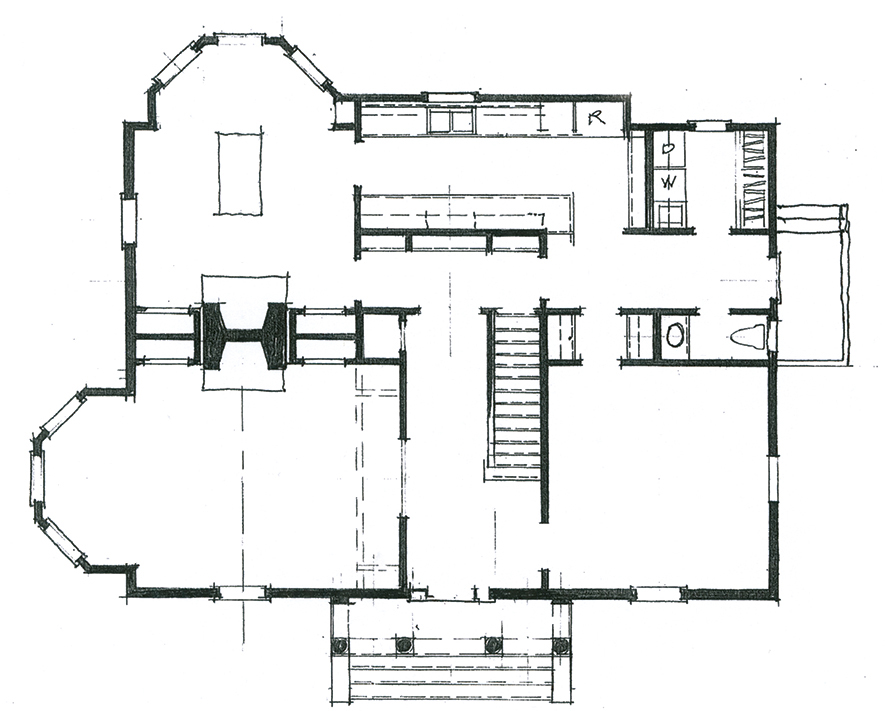

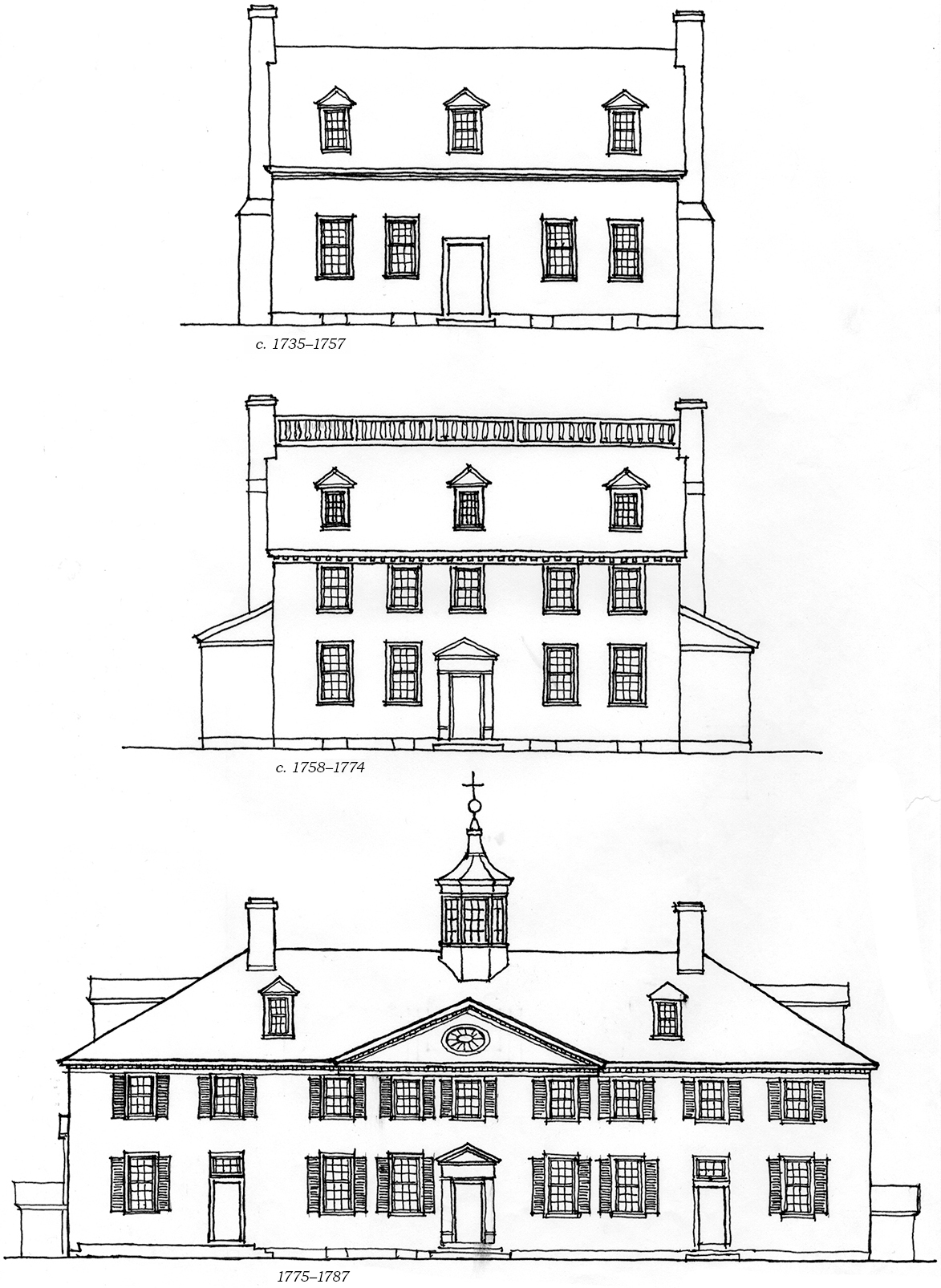

George Washington enlarged Mount Vernon between 1775 and 1777 in the latest fashion. The new dining/reception room was pure Adam (decorated much like Wedgewood china with Greek urns, sheaves of wheat, and garlands of flowers). Also at this time Washington added the two-story portico on the river elevation. Rather an anomaly, it is probably the single most recognized house in America. Undoubtedly few would recognize it in its original form, for it started life around 1735 as a typical one-and-a-half-story colonial farmhouse with a second story added in the 1750s. It took its final form in the Federal period (see illustration page 34).

The new freedom of the Federal period produced a lighter, more attenuated architecture which featured bowed windows, gracefully curved stairs, and tall 6 over 6 windows with delicate muntins only ¾-inch thick and large individual panes. Charles Bulfinch (1763–1844) of Boston, Samuel McIntyre (1757–1811) of Salem, Massachusetts, and William Thornton (1759–1828) of Washington were all proponents of this new and elegant expression of the late Renaissance ideal.

Thomas Jefferson sympathized with France in England’s Napoleonic Wars (1799–1815) and looked to the continent for his architectural stimulation and prototypes for his interpretation of Neoclassicism. France had supported us in our fight against England and Jefferson was our minister to France from 1785 until the outbreak of their revolution in 1789. His Neoclassicism drew from the original sources—true Roman buildings such as the Maison Carrée in Nîmes—rather than work distilled by late eighteenth-century British architects.

Whatever the political predilection of the architect, Federal and Neoclassical houses shared many standards and infused their plans and details with numerous innovations. Closets, as we know them, appeared, along with butler’s pantries and rooms with specific purposes. No longer were rooms invariably rectangular; elliptical, octagonal, and circular shapes were introduced as well as curved or bowed projections and octagonal bays. Service stairs and even indoor privies began to appear. Jefferson eliminated ceremonial stairways and even incorporated skylights into his designs.

By the end of the Federal period the classical idiom was recognized as an American way of building and set the pace for the Greek Revival of the next couple of generations. As settlers moved into the hinterlands, the Federal style had no time to take root before the popular mania for the Greek orders became established. Most Federal houses were built in towns founded before the Revolution.

Mount Vernon was originally built about 1735 by George Washington’s father as a typical unpretentious colonial farmhouse. It was enlarged and embellished with Georgian details in 1757–1758 and remodeled again during the Revolution. It took its final form by 1787.

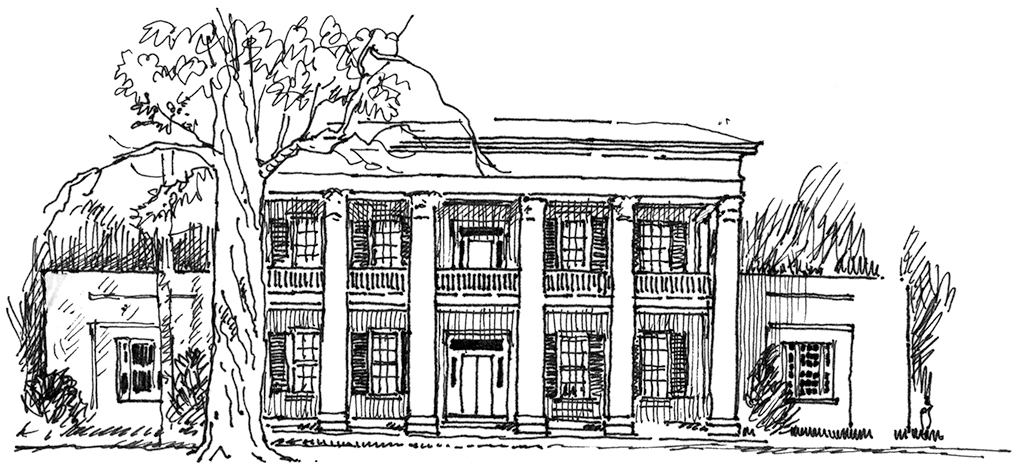

Though Andrew Jackson won the most electoral votes in the 1824 election, the vote moved to the House of Representatives and he lost to John Quincy Adams. Four years later, however, Jackson won with a clear majority of the nation behind him and was the first “candidate of the common man.” Jackson’s Greek Revival house The Hermitage was a symbol of the new age.

The Hermitage, Andrew Jackson’s home, near Nashville, Tennessee, built in the 1830s

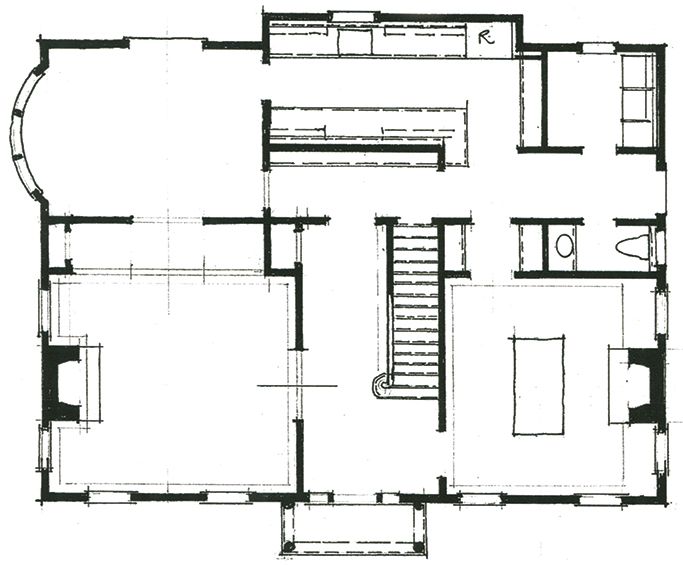

In the early Federal period, the colonies found expression in a refined and elegant interpretation of the prescribed Georgian. William Hamilton’s Woodlands just outside Philadelphia was among the first houses to be built in the new style. It was embellished with a two-story portico in the late 1780s. Window glass was now made in the United States and was available in larger sizes. Three-story houses, with windows decreasing in height on the upper floors, became increasingly common. Three-quarter-inch glazing bars gave a new elegance to the Federal house and the divided lights were often 10 inches by 12 inches or even larger. Windows were elongated with the sills almost at the floor level. Elegant balustrades were set just above the eave line and the roof pitch was reduced to 4 in 12 and perceived as virtually flat. The Palladian window, popular during the Georgian period, became more delicate and was a common feature of the Federal house.

The Woodlands, Philadelphia, 1787–1789

Charles Bulfinch returned to Boston from the London of the Adams brothers in 1786 and did much to alter Boston in the Federal period. The previous Georgian style deferred to the new influences from abroad.

Front doors with elliptical fanlight transoms and decorated sidelights became a feature of the Federal style. Wall surfaces were left plain. String or belt courses and occasional plaques with swags or sheaves of wheat might be the only decorative features. Considered elegant and rich by many admirers, the original Adam interiors in England were found by others to be garish and excessive in their gilded details and use of multicolored marble. The Adam style here generally showed more restraint and elegance in the understated playfulness of curved bays, oval rooms, and sweeping stairways. Some of the finest examples of the style can be seen in ports along the East Coast with strong ties to England.

FEDERAL 1780–1820

Thomas Jefferson’s architectural influence was pervasive throughout the former southern colonies, particularly in Virginia. Palladian principles and proportions influenced Jefferson. His first version of Monticello featured a double portico—Roman Doric below and Ionic above—and was decidedly Palladian in spirit.

Thomas Jefferson’s first version of Monticello, 1771

Federal orders were usually attenuated—the columns elongated and the entablatures often one-fifth the height of the column, instead of the one-quarter as in Palladio’s standards shown on pages 22–23. The Neoclassicists, on the other hand, adhered strictly to the formulae of “correct” proportion of the Roman prototypes and took few liberties with established precedent.

Palladio, however, was no longer the single dominant source for classical orders. Even Vitruvius was found to have edited and codified the Roman orders to suit himself. Archaeological discoveries continued to reveal wider variety in classical orders than had been previously supposed and the Neoclassicists drew from a wider selection of precedent. They rarely presumed to distort the proportions of the classical orders except in the subtlest way. Angled bays and tall windows, similar to the Federal buildings of the North, and articulated, symmetrical floor plans characterized the style. Introduced as a Roman Revival but superseded by the late 1820s by the ubiquitous Greek Revival, the style enjoyed a popular resurgence following the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 (see page 86).

One encounters occasional vernacular examples of the Neoclassical style, invariably with badly proportioned forms. Any naive attempt to imitate classical orders is the equivalent of pretentious writing with no sense of grammar, syntax, or spelling.

NEOCLASSICAL 1780–1825