6. THE PICTURESQUE 1840–1900

The mingled quaintness, beauty, and picturesqueness of the exterior . . . when harmoniously complete, seem to transport one back to a past age, the domestic habits, the hearty hospitality, the joyous old sports, and the romance and chivalry of which, invest it, in the dim retrospect, with a kind of golden glow, in which the shadowy lines of poetry and reality seem strangely interwoven and blended.

—A. J. Downing, Victorian Cottage Residences, 1842

The Picturesque movement was an expression of a nineteenth-century philosophy of architecture and landscape design. It derived from landscape paintings by artists who emphasized the harmony and integration of man, buildings, and nature. Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain were mid-seventeenth-century painters whose works were particularly admired for their picturesque qualities and were a source of picturesque theory. Many of the styles that evolved from this movement have been associated with the Victorian era.

The Gothic was the harbinger of the Picturesque styles. Real Gothic architecture of the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries derived its intrinsic style from an expression of its structural system. Walpole’s “Gothick” Strawberry Hill was a new costume for a fancy dress ball. The detailing had little or nothing to do with the actual structure. His house was widely publicized and initiated a fascination with the Gothic style that found its way to our shores in the 1840s. The Greek Revival and the Gothic Revival were the styles that bridged the change from the end of the Renaissance age to the new industrial era of the modern world.

Cronkhill, a small agent’s house at Attingham Park in Shropshire designed by John Nash (1752–1835) in 1802, was a key example of the Picturesque in the form of a rural Italian villa. It was the first interpretation of an idealized vernacular farmhouse from the popular picturesque landscapes and became the prototype of Italianate villas in America.

The classicism of the eighteenth century—whether rigidly orthodox or loosely interpreted and adapted to residential scale—was no longer the only accepted architectural mode. Words like “irregular,” “adaptability,” “informal,” and “fitness of purpose” became the slogans of the new Picturesque movement. The idea of a house in the country became increasingly important for the English middle class. The retreat, the romantic hideaway, and the pastoral shooting lodge all satisfied a need of the successful mercantile class on both sides of the Atlantic to escape from the realities of the source of their money. This rejection of the formal, imposing, classical house opened up all kinds of possibilities for inspiration and emulation.

The English publication of E. Gyfford’s Designs for Elegant Cottages and Small Villas and Small Picturesque Cottages and Hunting Boxes in 1806 and J. B. Popworth’s Rural Residences in 1818 reflected an increasing predilection for the quaint among the English middle class. These books nurtured a taste for the Gothic retreat, the Swiss chalet, the Italian farmhouse, and the “cottage orné.” With such variety of style, unity was achieved in a cohesiveness of scale, planning, and respect for the garden park.

Nineteenth-century England paid a tremendous price in social ills for its industrial and commercial growth. The order, grace, and dignity of the earlier Georgian era succumbed to a world of squalor, human exploitation, and industrial blight. There were social reformers—Charles Dickens, for one—who reacted against this new reality. The English Arts and Crafts movement, encouraged by William Morris (1834–1896), flourished in Victoria’s reign after 1860 and in this country after 1890. It was also a response to the negative aspects of the times and took the form of a romantic revival of the arts and crafts of an idealized past. People sought Ye Olde England, the good old days in an attempt to ignore the unpleasant realities of the present.

One positive force was a movement in domestic architecture toward a house for the then-modern age. In 1859 the designer William Morris commissioned Phillip Webb (1831–1915) to design a house near London. The result, The Red House, was seen by Hermann Muthesius as “the first private house of the new artistic culture, the first house to be conceived and built as a unified whole inside and out, the very first example in the history of the modern house.”*

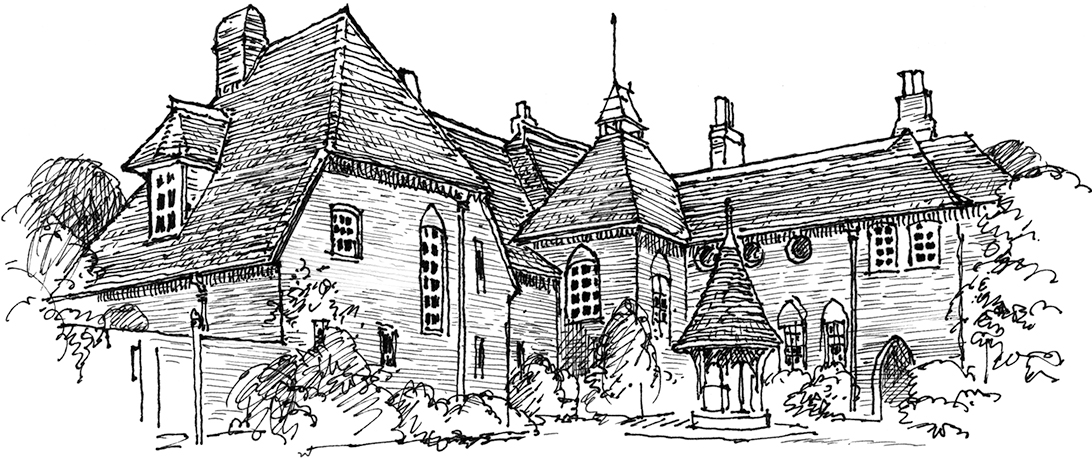

The Red House, William Morris’s house in Bexley Heath, Kent, by Philip Webb, 1859

The Red House set the tone for the work of Norman Shaw, W. E. Nesfield, E. W. Godwin, B. Champneys, and J. J. Stevenson. They were prominent among the principal architects in the so-called Queen Anne movement in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The term Queen Anne is really a misnomer and should not be confused with the Renaissance style that prevailed during the first fifteen years of the eighteenth century. The Victorian term, as Mark Girouard put it in his excellent book Sweetness and Light—The Queen Anne Movement 1860–1900, “was a kind of architectural cocktail, with a little genuine Queen Anne in it, a little Flemish, a squeeze of Robert Adam, a generous dash of Wren, and a touch of François I.”† Though mostly for rich clients, this new architecture was less pompous than the classical and, with the use of warm red brick, sash windows, and a Dutch intimacy of scale, provided the source for much of the American Picturesque architecture toward the end of the nineteenth century. It is important to note that the American Queen Anne style quickly developed a very different character, from the English. To call it the American Queen Anne would be a bit laborious but more appropriate.

Manor Farm, Hampstead, by Basil Champneys, 1881, is an example of English Queen Anne

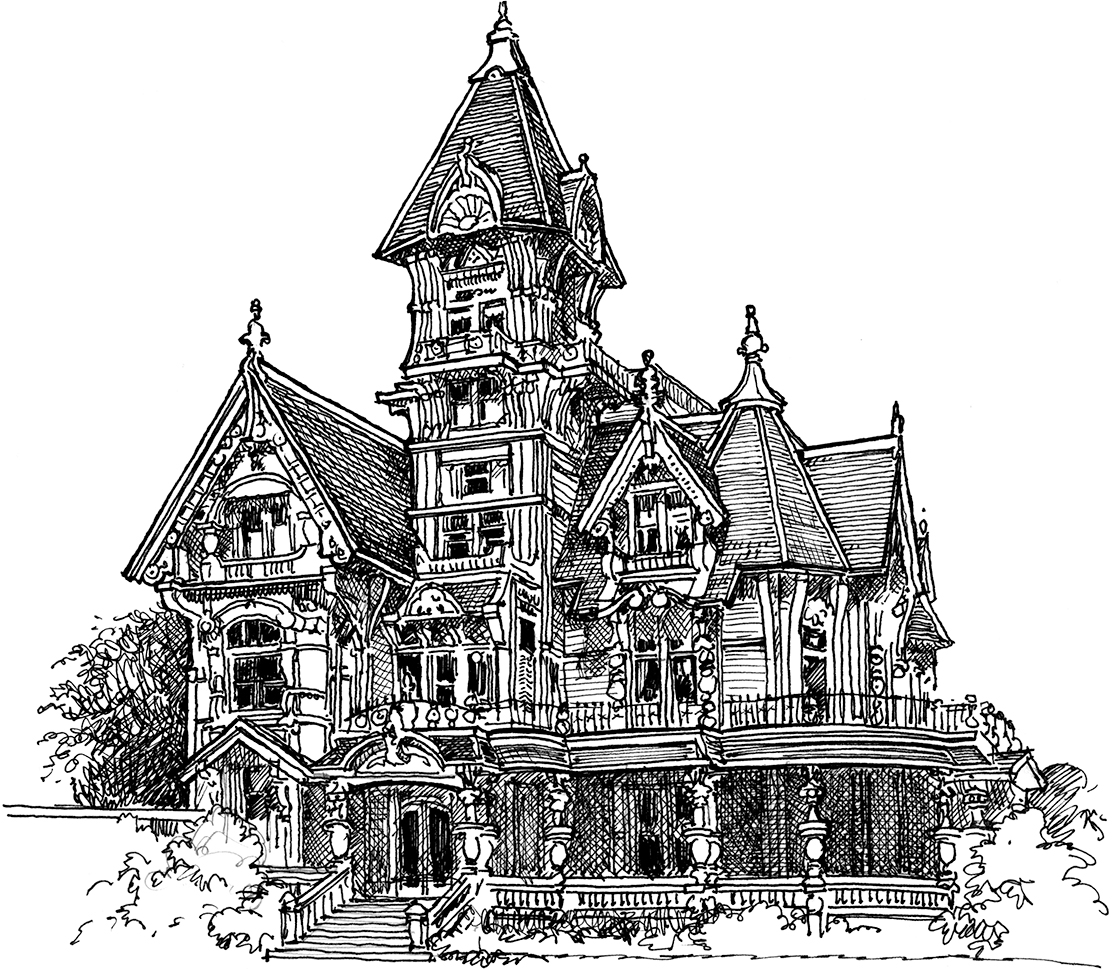

William Carson House, Eureka, California, by Samuel and Joseph Newsome, begun 1884, is the quintessential American Queen Anne

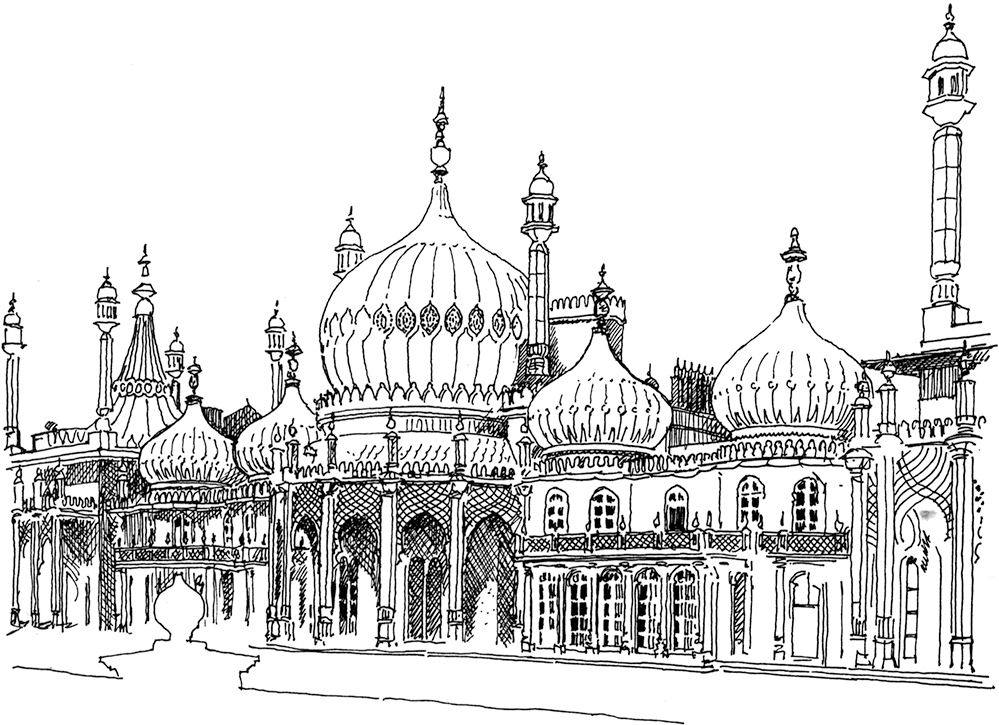

Sezincote, Colonel John Cockerell’s house in Gloustershire, by his brother S. P. Cockerell, c. 1803

Royal Pavilion at Brighton, by John Nash, c. 1818

Queen Victoria succeeded George IV in 1837 and ruled until January 1900. Her name has been associated with architecture throughout that entire era even more in this country than it is in Britain. The diversity of styles and character makes the term “Victorian style” almost meaningless. There are no less than eight distinct styles that are called Victorian in popular parlance, and many vernacular combinations could also be added to the list. In addition to the Gothic Revival, the list includes the Swiss Cottage, the Italianate styles, Exotic Eclectic, Second Empire, the Stick style, and the Queen Anne. One of the aims of this chapter is to sort out the principal styles that come under the general term Victorian so that each one can be appreciated for its own particular qualities.

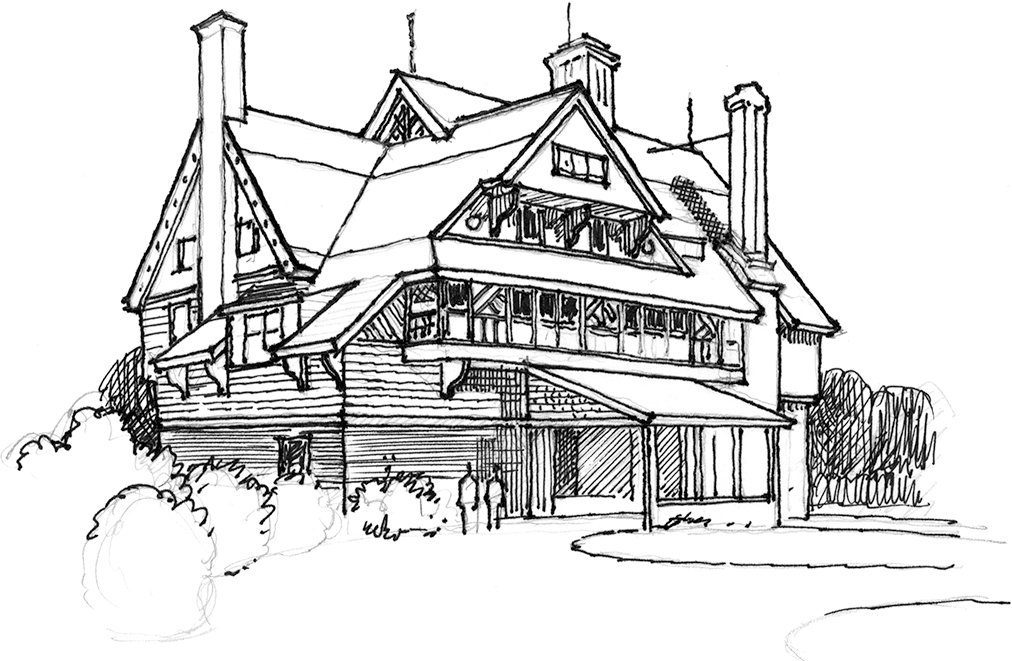

William Watts Sherman House, Newport, Rhode Island, by Henry Hobson Richardson, 1874, often considered the first American Queen Anne

Griswold House, Newport, Rhode Island, by Richard Morris Hunt, 1863

There is probably no more “picturesque” country anywhere, even today, than Switzerland. In his 1823 book Rural Architecture, or a Series of Designs for Ornamental Cottages, the Englishman P. F. Robinson recommended the Swiss Cottage style for residential designs. Andrew Jackson Downing suggested the Swiss Cottage style in his Victorian Cottage Residences, saying that anyone “fond of the wild and picturesque, whose home chances to be in some one of our rich mountain valleys, may give it a peculiar interest by imitating the Swiss Cottage, or at least its expressive and striking features.”

For the English Switzerland was “Protestant and clean.” It represented an idyllic land remote from their growing industrialization. Dickens had a small chalet in his garden and Queen Victoria imported one in 1853 as a playhouse at Osbourne, her retreat on the Isle of Wight. There is even a tube stop on the London Underground that commemorates an 1840 tavern built in the style near St. John’s Wood. Few Swiss cottages survive from the nineteenth century. The decorative details of the style, however, inspired much of the “gingerbread” which encrusted vernacular interpretations of the various Victorian styles.

In our era there is a perfect parallel to this escapist mentality. Vermont’s Stratton Mountain was developed as a ski area in the early 1960s and nurtured an Austrian theme. The ski school was Austrian and Tyrolean music contributed to the atmosphere. Most of the “chalets” (not “ski lodges”) looked like cuckoo clocks. They had shallow pitched roofs and typically a second-floor balcony beneath a gabled overhang. The railings had flat board balustrades with cutout decorative motifs. Heraldic shields abounded. This storybook architecture provides an escape from the world of business for the city executive today much as it did for his counterpart in the Victorian age.

Swiss Cottage from Andrew Jackson Downing’s The Architecture of Country Houses (1850)

SWISS COTTAGE 1840–1860

John Nash designed Cronkhill in 1802. Other Italianate houses based on the vernacular styles of northern Italy soon followed. They became increasingly popular in England and of course soon caught on here. Andrew Jackson Downing was the great proponent of the style.

In Victorian Cottage Residences, published in 1842, Downing wrote, “an Italian villa may recall, to one familiar with Italy and art, by its bold roof lines, its campanile and its shady balconies, the classic beauty of that fair and smiling land.” He also suggested that the “irregular” villa, through its “variety,” would evoke in “persons who have cultivated an architectural taste . . . a great preference to a design capable of awakening more strongly emotions of the beautiful or picturesque, as well as the useful or convenient.”

The villa as an English house type evolved in the eighteenth century but found great popularity in the Regency period of 1811–1820. Larger than a cottage and more cohesive than most farmhouses, the scale of a villa was appropriate for a family residence generally set on a modest amount of land near a city.

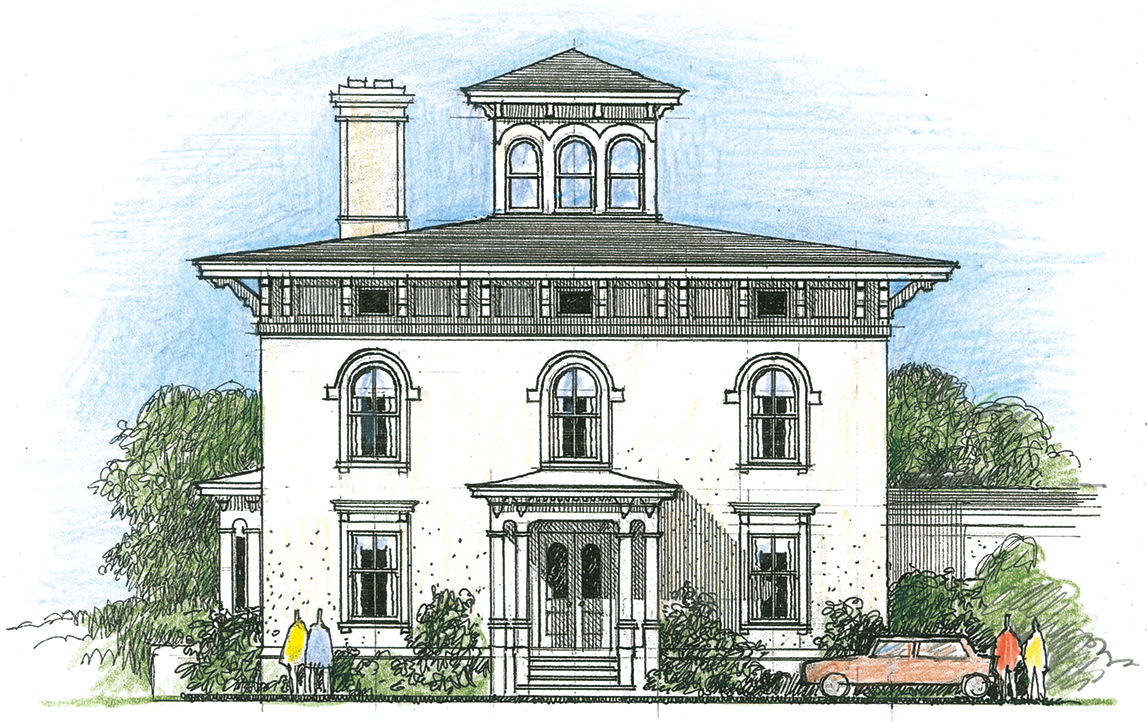

The tower is the key feature of this style and distinguishes it from the Italianate. Both styles have shallow pitched roofs with broad overhangs decorated with carved brackets. Wall textures are usually smooth, reflecting the original stuccoed surfaces. Tall windows, often with rounded tops with prominent crown moldings, and informal compositions with loggias and verandas are typical of the style. The Italian Villa style was inspired by the buildings in the painted landscapes of the French Romanticists Lorrain and Poussin.

Cronkhill Attingham Park, Shropshire, by John Nash, 1802

ITALIAN VILLA 1845–1870

The Italianate style was akin to the Italian Villa but did not feature a tower. So popular was it during the 1850s and 1860s that it was even called the American Bracketed style. (It was also called the Tuscan, Lombard, and simply the American style.)

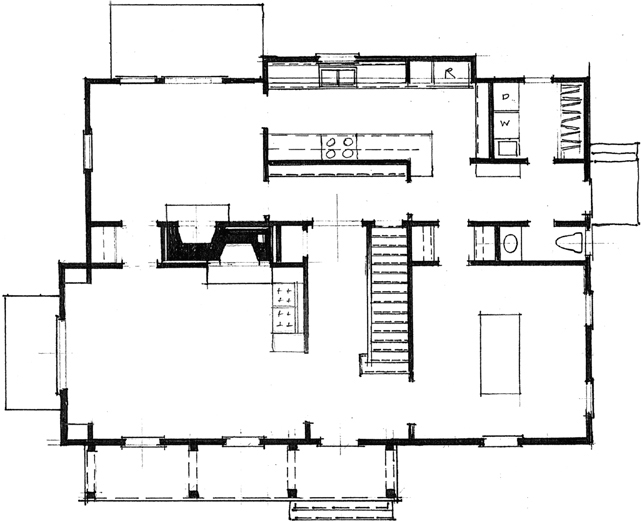

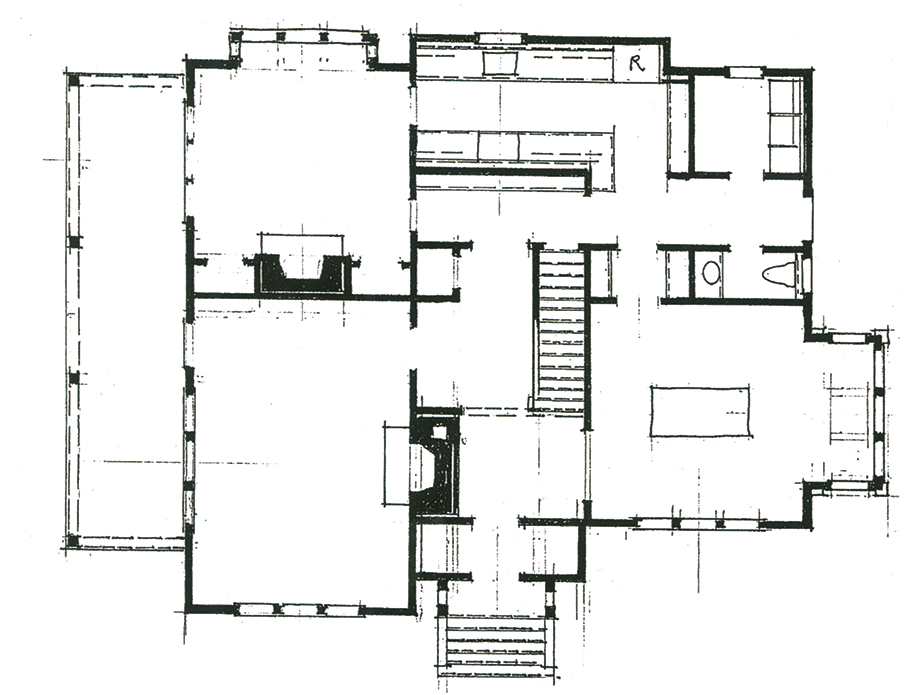

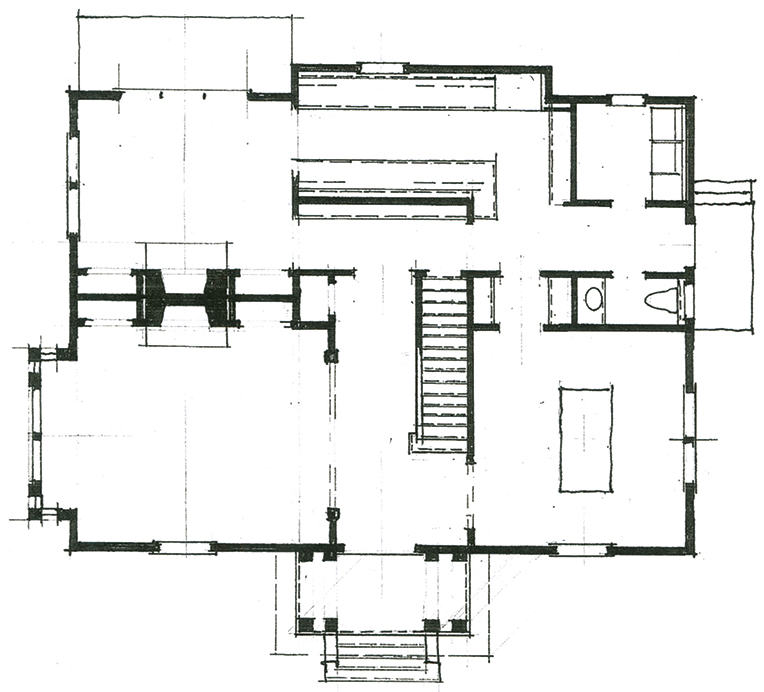

The decorative brackets that adorn the eaves of the Italianate house immediately identify the style. They were simple consoles either evenly spaced or often paired. The basic Italianate house style was less complex than the Italian Villa style, and brackets and verandas were often added to older farmhouses to give them a stylish uplift. Many Italianate houses were almost square in plan with high ceilings. The shallow-pitched hip roofs were often capped with a cupola or lantern at the very top. The attic was apt to have a row of awning windows between the eave brackets, not only creating additional head room but also making for a cool house in summer when the breezes could blow through the cupola windows and draw cooler air through the low attic openings.

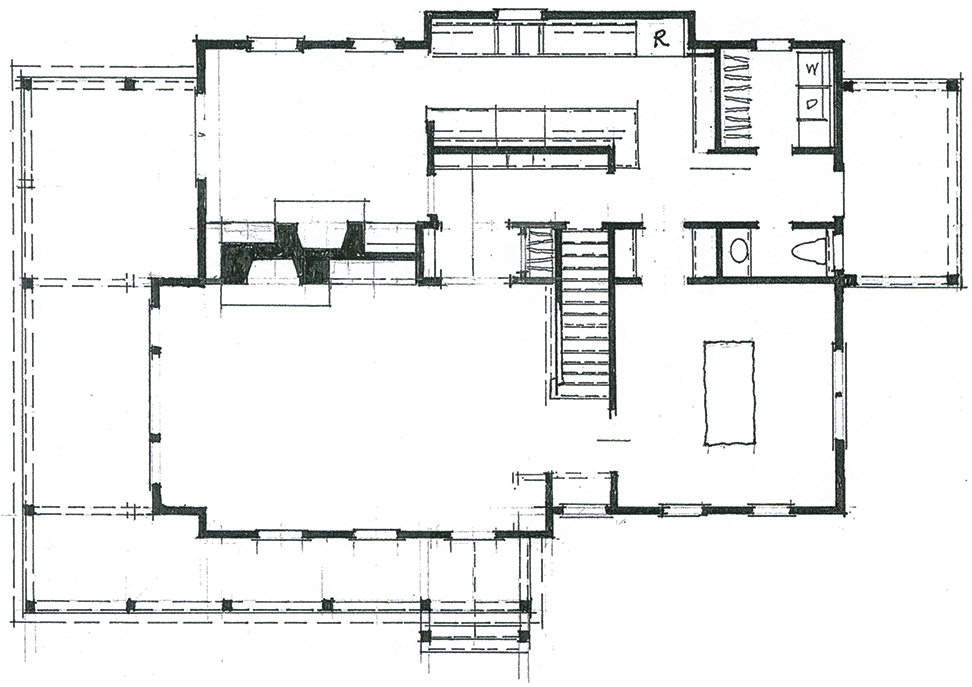

An eccentric named Orson Squire Fowler wrote a book called The Octagon House: A Home for All which was published in 1848 and revised in 1853. He was responsible for a modest fad which swept across the country for fifteen or twenty years. Some architectural writers designate the octagon house as a separate style. It is actually a building type, and most octagon houses were built in a simple version of the Italianate style. Fowler’s book is most entertaining and is in fact full of sensible advice about building an efficient and practical house.

An octagon house, c. 1860

Floor plan

ITALIANATE 1845–1875

ITALIAN RENAISSANCE REVIVAL 1845–1860

It may seem odd to include this revival in a group of Picturesque styles. Not all houses have to be quaint, however, to be worthy of portraiture. Though less fanciful than other popular styles it is just as much a Victorian style and warrants inclusion.

Sir Charles Barry (1795–1860) designed the Traveller’s Club built in London in 1819 and it became the prototype of this Victorian revival style. Simple flat facades, rectangular forms, and restrained decorative features characterize the style. Surface textures were smooth limestone or stucco. What columns were used were often limited to the entrance porch. The assertive cornice was proportioned to the overall height of the building. For example, if the Ionic order was used in the cornice, its height would be approximately one-thirteenth the height of the building from its base to the top of the cornice. Balustrade balconies, string courses, and tall windows extending almost to the floor on the main level were common features. The style was used for men’s clubs throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, and every town with any British roots that boasted an athenaeum would have built it in this style. Infrequently used for freestanding houses, it was and remained an urban or at least a town style.

Perhaps the best examples of the Italian Renaissance Revival are the brownstones built as blocks of row houses in New York City as Manhattan expanded northward after the Civil War. Three landmark examples of the style are the Philadelphia Athenaeum (1847), India House in New York City (1850), and the post office in Georgetown, Washington, D.C., which was built as the customs house in 1857. Though none is residential, each has the scale and character of a substantial house. This is perhaps the only style of the period that exuded refinement with minimal use of columns for decoration.

Post Office (former Custom House) Gerogetown, Washington, D.C.

ITALIAN RENAISSANCE REVIVAL 1845–1860

Most Picturesque houses in the nineteenth century drew from precedents in the dim and distant past. The love of the Picturesque was so widespread and fashionable that no one considered the construction of a folly or fake ruin as eccentric. Rather, one had to create something especially bizarre to appear exotic.

This romance with the past soon expanded to include stylistic elements of remote lands. Moorish bazaars, Indian palaces, Turkish mosques, and Oriental harems—alone or in combination—inspired many fanciful houses. The British have always respected eccentricity—particularly among the upper classes; Americans have generally viewed it with suspicion. But we have had our share of eccentric houses.

In 1803 S. P. Cockerell designed Sezincote in Gloucestershire for a retired nabob of the East India Company. It was complete with onion domes, minarets, and a flavor of India. John Nash’s design for the Prince Regent’s Brighton Pavilion built between 1815 and 1822 was the apotheosis of Picturesque fantasy. It was an Indian dream palace featuring a colossal assemblage of Islamic domes. (See page 54.)

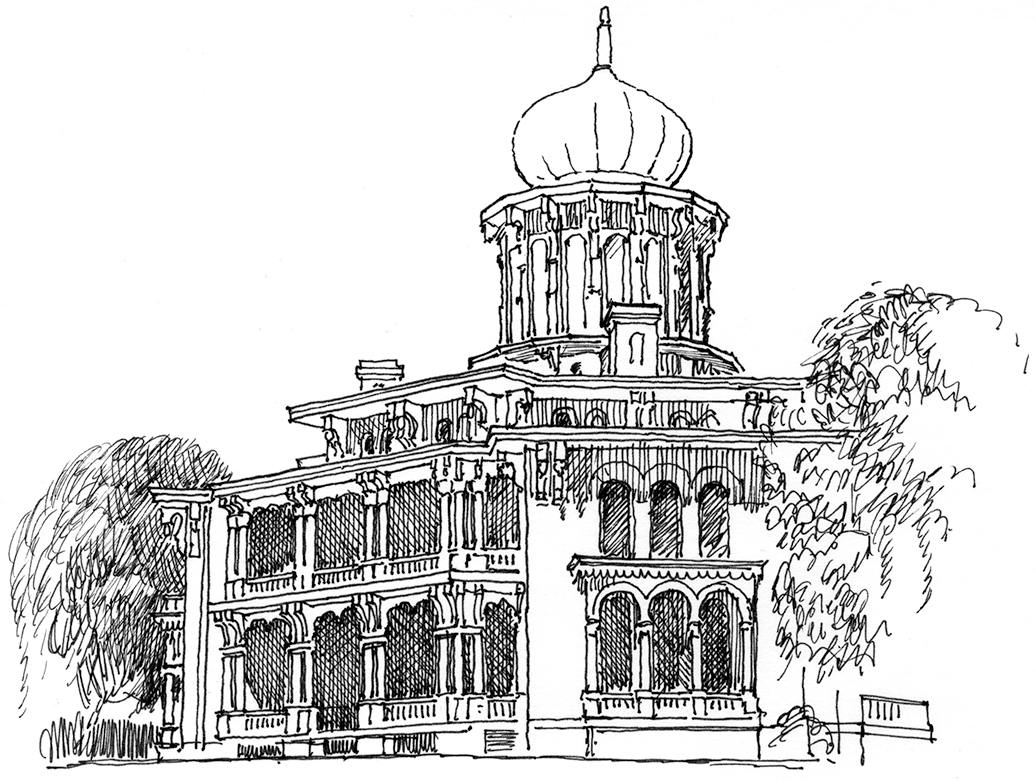

My favorite American contributions to Exotic Eclecticism are Samuel Sloan’s Longwood and Frederick Church’s Olana with its Moorish embellishments. The first was an unfinished 1862 octagon near Nanchez, Mississippi, and the other an 1874 fantasy overlooking the Hudson River in New York.

Longwood, 1862

Olana, 1874

EXOTIC ECLECTIC 1850–1875

Napoleon III (Louis Napoleon Bonaparte), Napoleon I’s nephew, became president of France in 1848. He appeared to practically all the French people as a chauvinistic leader on a white horse who would champion their interests over corrupt political opportunists. Limited by the French constitution to one term, in 1851 he summarily dismissed the assembly and seized power in a coup d’etat. After declaring himself emperor, he remained head of state for almost ten years.

Louis Napoleon transformed the old Paris into the city of grand boulevards that we know today. He enlarged the Louvre between 1852 and 1857 and set the fashion for a new style. The mansard roof is the single key feature of the Second Empire style. It is a double-pitched hip roof with large dormer windows on the steep lower slope. The eave is commonly defined by substantial moldings and supported by Italianate brackets. There are also moldings capping both the top of the first roof slope and the upper slope; the upper part of the roof usually intersects with a flat roof over the middle of the building. The effect of this construction was an entire usable floor at the attic level. Named for the seventeenth-century architect François Mansart (1598–1666), the mansard roof’s enlarged attic supposedly provided an additional rental floor in Parisian tenements where the zoning ordinance limited the number of stories.

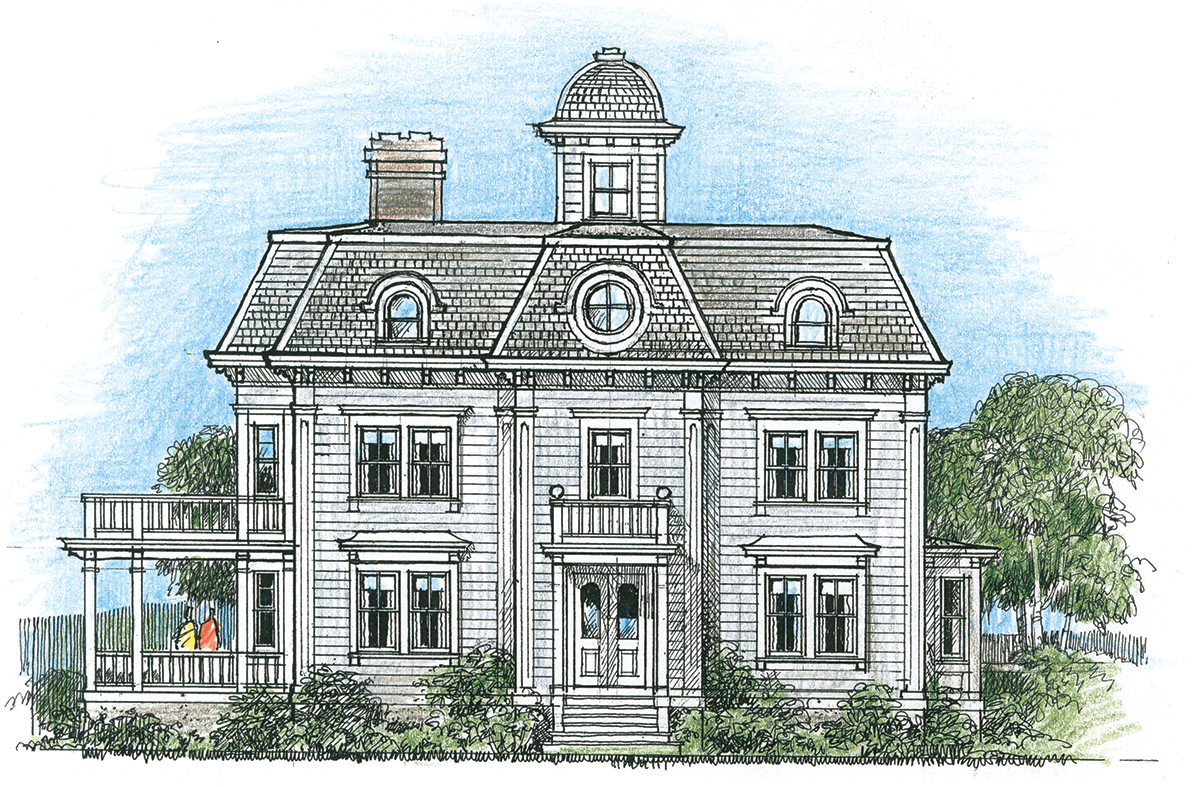

It is puzzling that the official architectural style of an authoritarian government would appeal to Americans. However, a mansard roof now seems perfectly natural on a Vermont farmhouse. The style remained extremely popular for twenty years before it was superseded by the Colonial Revival styles after 1876.

Typical mansard roof profiles

SECOND EMPIRE 1860–1880

The Gothic Revival, the Swiss Cottage, and the Italianate styles found impetus in European precedent. They were the initial Picturesque styles. American designers soon created a new style, however, that sought character from complexity of form and an inventive expression of structure. In his Village and Farm Cottages published in 1856, Henry W. Cleaveland captured the essence of this new and energetic way of building: “The strength and character of the new style depends almost wholly on the shadows which are thrown upon its surface by projecting members.” Cleaveland did not use the term Stick style; that term was coined by Yale professor Vincent J. Scully, Jr., a hundred years later.

The character of this style derives basically from steeply pitched roofs and vaguely Elizabethan vestiges. The celebration of structure in the flamboyant projections, brackets, and rafter tails was reinforced by the playfully sculptural quality. Sometimes evident are fancy decorative details that were either invented wholly or derived from such diverse sources as Swiss cottages and Oriental temples.

The principal feature of the Stick style is the pattern of wood boards—vertical, horizontal, and sometimes diagonal—that suggests a structural framework beneath the clapboard skin. This Elizabethan half-timbered appearance may, in fact, not articulate the actual structure, for balloon frame construction was in common use by the 1850s and the suggestion of a braced frame is somewhat illusory. It was a very popular style for churches during this twenty-year period; indeed most towns on eastern Long Island have one.

Gervase Wheeler’s Rural Homes was published in eight editions between 1851 and 1869. It did much to promote the Stick style. Even Richard Morris Hunt, best known for his French Chateaux, designed perhaps the most famous Stick style house of all: the Griswold House in Newport, Rhode Island, built in 1863.

Griswold House, Newport, Rhode Island, by Richard Morris Hunt, 1863

STICK 1855–1875

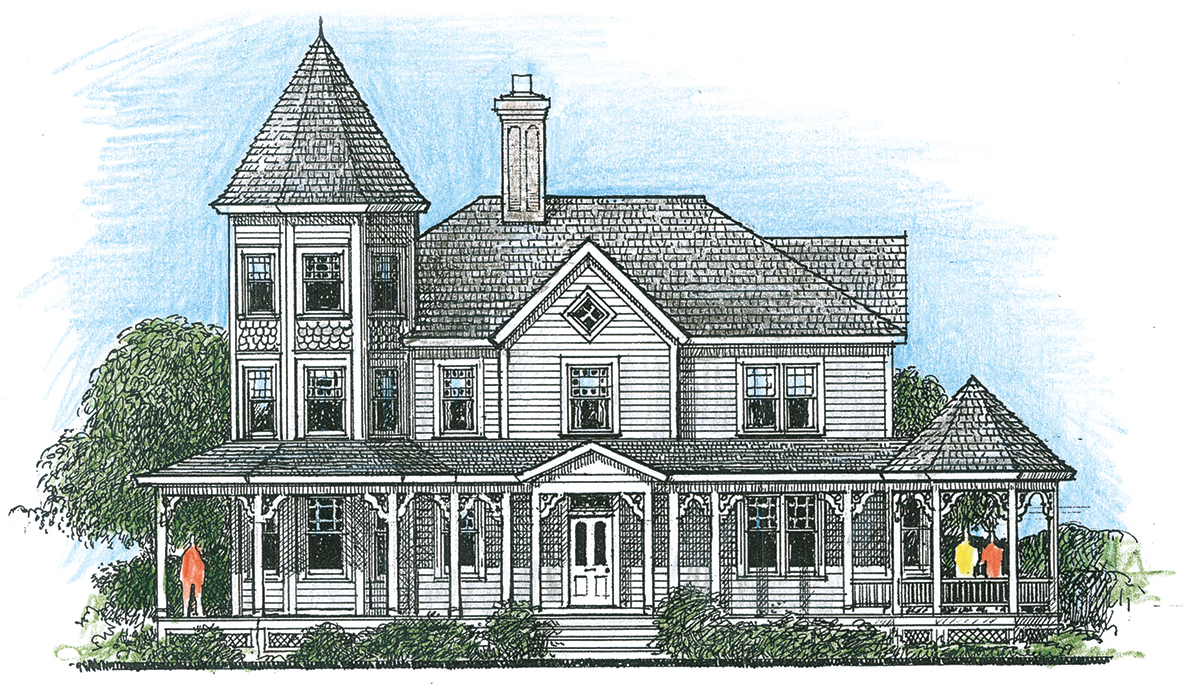

The Queen Anne style is almost the quintessential style of Norman Rock-well’s America. Popular in its heyday, it has recently been rediscovered and is often celebrated with wild “boutique” colors. The style evolved in England as an outgrowth of the Arts and Crafts movement of the mid-nineteenth century. The British government built two half-timbered buildings at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. These structures were the impetus for the Queen Anne style in this country.

Henry Hobson Richardson’s William Watts Sherman house built in New-port, Rhode Island, in 1874 is usually considered the first Queen Anne house by an American architect (page 55). It featured quasi-medieval half-timbering, assertive chimneys, and a varied but cohesive surface pattern—all deftly handled by one of our great architects. The style quickly became popular here but was not favored by architects. They generally preferred the Shingle style which evolved from some of the same sources but used a more cogent vocabulary. The Queen Anne style was promoted in publications like the American Architect and Building News, our first architectural magazine, and was sold precut by mail-order companies. Components like knee braces, brackets, and spindles were also shipped across the country to embellish older vernacular houses.

The American Queen Anne differed from the English in its exuberant use of scroll work and applied detail. The English built brick houses and Americans wood. The Carson House in California, begun in 1884, is the ultimate example of the style (see page 53). Floor plans were usually open and free-flowing. Double parlor doors were popular as were corner fireplaces. America’s love affair with the porch or veranda found fulfillment in the Queen Anne style. Turrets, towers, and fanciful gazebos characterized the style along with varied shingle patterns and wall surfaces. One cannot call it the Victorian style—it is simply one of many.

The term Eastlake is sometimes confused with Queen Anne. In the 1870s and 1880s decorative components were mass produced by mechanical lathes and jigsaws and were used to embellish eclectic houses with fancy scrollwork, turned ballusters and porch posts, beaded spindles, and sometimes even wrought-iron embellishments. The English interior designer Charles Locke Eastlake (1833–1906) disassociated himself from the style that bears his name.

QUEEN ANNE 1880–1910

* Muthesius, Hermann, The English House (Berlin: 1904; New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1979).

† Girouard, Mark, The Queen Anne Movement 1860–1900 (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1977; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984).