10

Surplus People

Maclear – Matatiele – Pietermaritzburg – Johannesburg – Home

Some people plead that the right to own land should be granted to Bantu living in

White areas … If these concessions are granted

such a population will not be satisfied

with social rights only, but will certainly insist on the franchise and make further

demands … My department would view the alienation of White land as a nail in the

coffin of the White nation and of the fundamental principle of apartheid. We shall

therefore be only too glad to assist those Bantu who are interested in buying land in

towns

in their respective homelands.

I. P. van Onselen, Secretary for Bantu Administration and Development (1972)

Maclear, 26 July 1993

When Jim switched on the TV news this morning we saw a bloodstained church floor strewn with blanket-covered bodies. It is assumed APLA killed those eleven people, and grievously maimed many more, in last evening’s gun and grenade attack on Kenilworth church in Cape Town. The Hurters exclaimed that only blacks would slaughter people at prayer, within a church building, but I had to contradict them. Northern Ireland has endured an identical atrocity in a rural church in Armagh.

Over the forty-five mountainous miles from Elliot to Maclear a formidable gale blew either against or across me. Here all the telephone lines being down has closed both banks – most improbably there are two – and I must live on credit in this friendly no-star hotel where the last guest checked out sixteen days ago.

Maclear is a dispirited little place. One can’t buy cheese, butter, yoghurt, amasi, even sardines – or a daily newspaper in any language. The Jo’burg Sunday Times arrives on Wednesdays, the bread is stale and black/white relations are extremely uneasy. In part, this has to do with the township’s grazing land having been seized only a few years ago for yet another commercial forestry plantation. (Approaching Maclear, one sees a landscape devastated by this development.) However, some local blacks supported the seizure; South African Paper and Pulp Industries (SAPPI) gave much desperately needed employment while the land was being cleared and planted. But now fewer jobs are available and the grazing is gone for ever – or until such time as there is a revolution more radical than anything envisaged by the ANC.

Tonight the hotel business is booming; I have three fellow-guests – two Xhosas and an Afrikaner – all employees of a cane-spirit company. (One of the favourite township drinks: cheap and nasty.) Here is affirmative action in practice, the white rep training blacks in a dorp ladies bar. An interesting tableau, the English-speaking regulars being carefully polite, the blacks ill-at-ease behind an over-jolly façade. One farmer has just returned from his first journey overseas, a visit to cousins in Wales. South Africans, he assured us, don’t know what real apartheid is – they should see how things are between the English and the Welsh! He saw it for himself when an Englishman entered a pub and everyone spoke Welsh to exclude him – how’s that for racism? The blacks registered shock/horror and agreed no such thing could ever happen in South Africa.

The same, 27 July

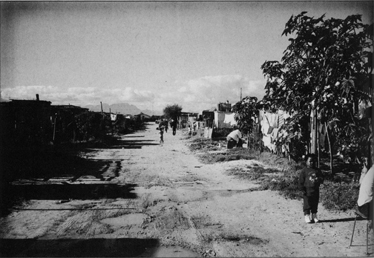

Sheer 1,000-foot table-tops almost completely surround Maclear and on one is concealed the township. When I climbed up this morning, invited by Mrs Ntloko who runs the clinic, I found an extremity of destitution that makes Zola seem affluent. Mrs Ntloko introduced me to several men who, having found their first job on the forestry project and become accustomed to earning, are now again unwaged and seething with anger; recently they had to sell their cattle for lack of grazing. Equally angry are the hundreds of ex-miners, sacked during the past few years from worked-out Rand gold mines. This community, like countless others, was dependent for generations on miners’ wages. But South Africa never ceases to surprise. Even the angriest of the men apologized to me, as a white, for the Kenilworth slaughter. ‘We are very sorry, that was bad, we don’t like it.’

At noon the bank opened but no cash was available until 3.30. The manager tried hard to put me off the Transkei. ‘They’ll steal your bike in Mount Fletcher! And that track is so rough you’ll be days getting there. Why not let me give you a lift back to Elliot? You could go on to Jo’burg through the Free State.’

Tomorrow I mean to take the sort of precautions that always make me feel silly. Normally my journal travels in a pannier-bag, my camera around my waist and the binoculars over a shoulder. While in the Transkei I’ll carry my journal over a shoulder (under my shirt) and the camera and binoculars in a pannier-bag. This apprehension is uncharacteristic but Maclear’s blacks are – it has to be admitted – slightly unsettling.

In the bar this evening a young man put on the Mandela turn, a popular entertainment. From under the counter came one of those shockingly realistic rubber masks that cover the whole head, not just the face. These are repulsively clever caricatures, the unmistakable Mandela features modified to present a monkey-man. The wearers mockingly mimic Mr Mandela’s voice, making Winnie-related speeches which provoke guffaws of ribald laughter, or putting PAC and APLA slogans into the mouth of their President-to-be. Among the white hoi polloi no distinction is drawn between the ANC and the PAC, a symptom of their uninterest in their own country’s political evolution.

Mount Fletcher, 28 July

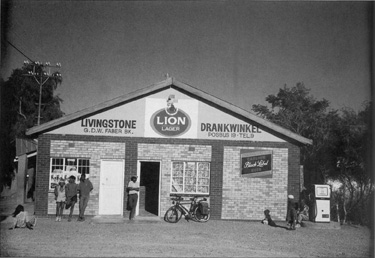

This is being written under the influence of drink. A lot of drink, consequent upon the locals’ determination fittingly to celebrate the arrival of a white tourist! It’s unlikely they’ll shoot me hereabouts: alcohol poisoning is the main hazard. I can’t imagine what the potation is (not any form of beer) – it comes out of a ginormous tin kettle and my liver will take weeks to recover. When I arrived, freewheeling down the steep main street, the whole town came to a halt. Stopping at the bottle-store, I was at once surrounded by ten or twelve grim-faced young Comrades. (By now I can tell a Comrade at a glance; they have a persona all their own.) But quarter of an hour later everyone was smiling and I had been persuaded to spend two nights here.

The same, 29 July

The above entry was curtailed by the contents of that kettle.

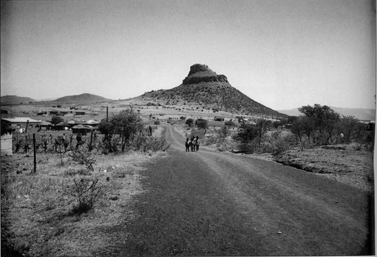

Yesterday’s thirty-seven miles were the most exhausting – and among the most beautiful – of this whole journey. First, a very steep two-mile climb from Maclear to a wide plateau where the sun rose over a distant range of strangely peaked mountains, the peaks all leaning sideways as though pushed out of shape. In that slanting light and clear air each colour was vibrant: the red-gold of grassy slopes, the dark yet glowing green of trees marking watercourses, the brown-gold of maize fields.

Over the next eight miles I met no one. Then from the plateau’s edge appeared the Transkei beyond a deep valley: countless tiny dwellings on barren hillsides. The Halcyon Drift ‘border’ post was manned by two white soldiers, three black police officers and an Alsatian tethered to an armoured vehicle. The white cyclist enraged this creature; he literally foamed at the mouth and almost broke his chain in a frenzied effort to get at me. One soldier glanced at my passport, handed it back, then asked my nationality. His mate described as ‘suicidal’ my entering the Transkei unarmed.

Slowly I pushed Lear out of the valley on one of the worst roads I have ever endured. Here a truckload of Mount Fletcher folk, who had stopped to pee, gave me a heart-warming welcome, counteracting the recent build-up of ‘Transkei tension’. Immediately I knew this was going to be a happy experience, a feeling reinforced when Joel joined me, full of curiosity and chat. Elsewhere in Africa such encounters occur daily, here they are very rare.

Joel, a 23-year-old road worker, wants to be a teacher but has had to take a menial job to feed the family: parents in poor health, an elder sister crippled by polio, plus a wife and two children. As we walked to the ridge-top he told me about his three cows whose calves were stillborn because of the drought. Drought-stricken white farmers receive government aid – more than R3 billion last year – but blacks must suffer their losses unaided.

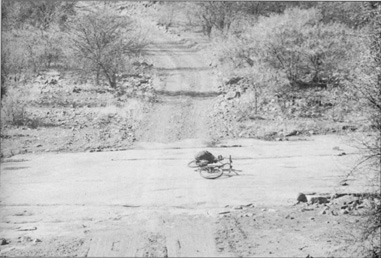

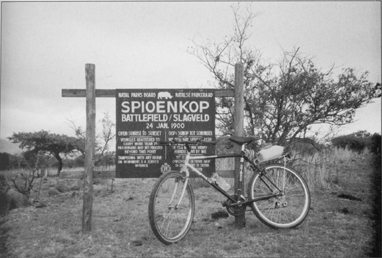

As we passed a gigantic new earth-mover abandoned by the wayside, Joel mentioned a plan to tar this Maclear–Mount Fletcher road. When work began some months ago he was one of the team breaking rocks and scattering them on the surface as a foundation. But the money ran out; under Transkei’s grotesquely corrupt puppet regime such crises are common. I had to walk the next twenty-five miles, dragging Lear over these large, loose, sharp fragments of mountain.

Although in white terminology Katkop is a ‘village’ it extends over several square miles (or rather, long miles) and here live uncounted thousands, far from water, without electricity, chronically short of firewood and grazing. About one-third of the dwellings are round thatched huts – the most skilful thatching I’ve seen since Cameroon – the rest are tiny oblong shacks, their tin roofs stone-anchored. Many are brightly painted – duck-egg green the favourite shade, but also lemon, pale pink, buff, sky blue. Some external walls are decorated with elaborate traditional designs in red, black, brown, white. Some minuscule windows wear incongruous suburban lace curtains tied back with pretty bows. Every few miles a tiny ‘café’ or huxter shop offers basic sustenance. The local litter consists almost entirely of plastic bags fluttering in the breeze on rusty wire fencing, itself a form of litter left over from the days when this land was white-owned.

Here the heights and depths are truly awesome. This is a red-rock landscape, deeply riven by irregular gorges below 2,000-foot precipices – a topographical chaos of visual splendour leaving little space for human habitation or cultivation. Yet in an emotionally muddled way I rejoiced to be in an area where some traces of ‘normal’ African life remain. Little herd-boys sat on high boulders guarding their pitifully small herds of cattle, others walked behind a flock of goats on a contour footpath, coloured blanket draped gracefully over a shoulder. Women were laundering blankets in scanty streams, then children carefully spread them to dry on tennis-court widths of smooth polished rock. Blanket-wrapped men rode small sturdy Basuto ponies up and down precipitous slopes – sitting straight-backed, their feet almost touching the ground. White South Africa’s landscapes, however beautiful, remain memorials to apartheid – their unpeopled spaces cruel, black activity channelled towards the baas’s enrichment.

Beyond Katkop came a mysterious region of crumpled dark-grey rocks, uncannily resembling giant crocodiles or prehistoric monsters. Then we crossed a high pass, the gradient making my struggle to drag Lear over that surface like some medieval penance for the most heinous of sins. But my reward was a scene of the wildest splendour – the opposite mountain walls golden in the noon light, against an intensely blue sky. I half-regretted getting to the top, from where could be seen the next ‘village’, Lalangubo, very far below.

Four (mostly downhill) hours later Mount Fletcher appeared in a wide valley, bounded to east and west by long low ridges.

As the Comrades escorted me from the bottle-store to the Castle Rocks Hotel we were followed by excited children and adolescents, some exclaiming at my achievement (as well they might!) and shouting friendly questions. Unsurprisingly, no washing water was available until morning. Then Mr Nxesi – a one-eyed raggedly dressed elder who speaks near-perfect English – swept me off to his kraal of thatched huts on a distant hillside. There that potent kettle was produced and an impromptu party laid on for the ‘brave lady from Ireland’. (Xhosa songs and dances – shades of Mafefe!)

Before the contents of the kettle took effect (a brief period: my tummy was very empty) we discussed regional politics. Said Mr Nxesi, ‘Comrade Mandela isn’t tough enough, he’ll never control our robbers in Umtata [Transkei’s capital]. Money is power. And our Mafia is numerous, thousands will fight to keep jobs and perks. Poverty isn’t the worst thing the Bantustans did to us. The worst is corruption – so much money from Pretoria! Our leaders and their hangers-on are destroyed. Destroyed in their souls.’

I refrained from questioning Mr Nxesi about his fluent English, a question with the implied corollary, ‘How come an educated man lives in such poverty?’ But I had my suspicions confirmed today. He lost an eye, and his job, in a drunken brawl; not so long ago he was head of the English department in a black university. The kraal is his ancestral home; last year he had to sell a bungalow built in happier times. And his wife has left him. Sad …

The Castle Rocks Hotel – and Mount Fletcher in general – could be said to prove a white point. Once this was a typical small-town hotel, its two rows of bedrooms overlooking a wide lawn. Now everything is ramshackle. And the lavatory is inaccessible; one has to find the person with the key – and who is that? At any given moment, where is s/he to be found? When those questions prove unanswerable I use my mug as a jerry and tip it out the window, as did many London citizens in the seventeenth century to Pepys’s distress. Here no distress is caused, only astonishment on the part of adjacent livestock: hens, geese, goats and a pathetically lean cow. I’m writing this with my room door open and a hen and ten fluffy chicks have just wandered in to hoover the floor – expecting, and finding, numerous crumbs left by the last occupant. In Mount Fletcher, with fowl busily pecking around my bedroom floor and that cow scratching her neck against my windowsill, I feel more at ease than I ever could in a dorp hotel. Also, R30 covers the cost of supper, room and breakfast, for which one pays at least R130 in ‘South Africa’.

In contrast to the dorps’ crowded hotel bars, neither bar here is much used. Both are dingy, ill-lit, stale-smelling, their shelves almost bare, equipped only with three unsteady stools and two glasses (one each!). Most customers sit on the stoep’s parapet, high above the main street where noisy geese, minute black piglets and another bony cow nibble and root in the short brown grass. The pavement slabs have long since been removed to serve some other purpose.

At present Mount Fletcher is sorely afflicted by political dissension, its ANC activists disunited. The Mafia of whom Mr Nxesi spoke may be encountered in government offices overmanned by incompetent officials. In the ANC office – which, rather confusingly, doubles as a doctor’s private clinic – Dr P— pointedly ignored my arrival while continuing to operate his computer, the screen showing a list of expensive drugs. Then, having put Whitey in her place, he delegated Mrs Sokhupa, who describes herself as a ‘social worker’, to show me round the hospital founded in 1934 by a philanthropic Englishman. The original single-storey dark-brick building is pleasant enough, the jerry-built addition less so. The nursing staff impress more by their kindness to patients than by their knowledge. They complain, with good reason, about shortages: of medicines, bandages, oxygen, bedpans, wheelchairs. The wards and corridors were cleanish – but only ish. Nobody seemed sufficiently AIDS-aware to take seriously the need for unwavering vigilance. Yes, it’s a bad disease. But Transkei people don’t get it. The main worry is an increase in TB deaths.

The hospital’s director is a Kampala doctor, amiable and courteous – much taller and darker skinned than the average Xhosa. He invited us to drink tea in his roomy, comfortably furnished bungalow on the edge of the compound, with a fine view of the town below and the hills beyond. On the way we passed through a colony of flimsy rusting caravans parked close together: the nurses’ quarters, each small caravan accommodating two.

The doctor had felt no scruples about taking this job in 1985 when State repression was at its worst – the Last Stand. In Uganda he couldn’t earn such a salary and he had to think of his family: four motherless children to be educated, a dependent father and aunt … Remembering how implacably much of the white world boycotted South Africa – cutting its citizens off from the BBC and isolating academics from the latest research – it is ironic that so many blacks were then hurrying south to support apartheid directly by availing of good job offers in the ‘Bantustans’.

Today the secondary school is closed; either the teachers or the pupils are on strike – maybe both. ‘The teachers are so ignorant it doesn’t matter,’ said Mrs Sokhupa. ‘They can’t even keep the kids sitting down. This year I’m sending my two sons to Elliot, to a good white school. The other kids treat them badly but I say it doesn’t matter. There they can learn – if I pay big money!’

According to Mr Nxesi, the under-30 generation hereabouts is largely illiterate. Many children don’t start school until they are 8 or 9; only then can they walk the necessary distances, up to sixteen miles daily. Even more detrimental, most boys drop out after circumcision at the age of 16. It would be too humiliating for men to have to accept the authority of their own age-group – any teacher under 40.

There was much rejoicing today when light rain fell for an hour; this morning the hotel dishes were rinsed in my washing water – after I had washed. Out of a similar water shortage came my (and my daughter’s) Madagascan hepatitis-A.

This is a soothingly silent town; most people are too poor to afford ghetto blasters.

Matatiele, 30 July

I had just commented on Mount Fletcher’s tranquillity when the party started. A newly arrived army platoon was celebrating its last night of freedom before barrack life closed in. End of tranquillity.

Yesterday morning a bucket of steaming water and a teapot of coffee (no tea available) were brought to my room by a buxom young maid with a smile like the sunrise. Later, I enjoyed a substantial breakfast of fried eggs and liver. But this morning – nothing. The dining room was shambolic, the entire staff AWOL. As I packed, several hungover teenaged soldiers, clad only in underpants, came wandering in and out of my room – fascinated by Lear’s panniers – and deplored no water, no breakfast … The lack of water seemed to bother them most. Soon they had to report for duty and how could they be expected to don uniforms before washing?

On the road to Matatiele – new and velvet-smooth – the taxi traffic was heavy and the concomitant litter repulsive. For South Africa’s prodigiously littered countryside all races are to blame. James Bryce, visiting ‘white’ Beaufort West in 1897, noted, ‘Most of its houses are stuck down irregularly over a surface covered with broken bottles and empty sardine and preserved meat tins.’ A century later, cyclists are seriously at risk when speeding motorists open windows to dispose of bottles.

This small market town is just over the ‘border’ in Natal. During my afternoon’s dander I saw only two whites, apart from busy storekeepers. Xhosas throng the streets, many wrapped in colourful blankets, and the pavements are piled with hawkers’ goods. The whole scene – noisy, bright, animated, scruffy – is the very antithesis of your average dorp.

Matatiele is reputed to be an APLA/PAC stronghold and by sunset a dozen young APLA warriors had occupied the ladies bar. Already they knew all about me (slightly disconcerting if not surprising) and were keen to publicize their Africanist ideology. The most articulate and forceful favoured anonymity, so let’s call them Tom, Dick and Harry.

‘We don’t believe in killing foreigners,’ explained Tom. ‘Not in the Transkei or anywhere else. It’s the boere does those murders, then blames us.’

‘But we do believe in “One Settler, One Bullet”,’ said Dick. ‘Why not? Settlers have a legal right to our land, they tell us, through “armed conquest”, OK, to get it back we use violence – right?’

Harry boasted, ‘We’ve more and more township kids joining our struggle.’ (This is untrue.) ‘They don’t trust the ANC, they know the capitalists have bought them. A new South Africa – what’s new? Without armed action there’s nothing in it for the exploited. Who’s negotiating for them? We’re only violent because the whites won’t back down, not really, unless we fight.’

Underberg, 31 July

Today I broke a rule, arriving here an hour after sunset. Reason: a strong relentless headwind over the eighty-five hilly miles from Matatiele.

For hours commercial forestry frustrated me, completely concealing one of Africa’s most splendid mountain ranges. These pines and bluegums, covering the lower slopes of the Drakensberg like some disfiguring disease, retain the water that previously filled rivers and are an ecological and social disaster. Each tree’s roots reach down some sixty feet to groundwater level and each absorbs more than 100 litres a day. Largely because of the activities of SAPPI and MONDI, South Africa’s dwindling rivers have become an international problem, threatening the survival of countless peasant farmers in southern Mozambique.

In Underberg’s hotel bar a party of transplanted Rhodies gave me a heroine’s welcome.

‘From Matatiele today on that bike? Hey, you’re some woman!’ Wenwes like action and physical stamina and what they imagine to be daring deeds – like cycling through a very small area of the Transkei.

Ixopo, 1 August

More plantations today, including miles of nurseries – proof that SAPPI and MONDI are planning ahead, confident of being unhampered in the new South Africa. To escape, I took a narrow dirt track along the edge of a small separate segment of the Transkei which the APLA warriors had warned me to avoid. (Hence my Underberg detour, instead of the direct route through Kokstad and Umzimkulu.) This track overlooks a series of deep, wide, winter-brown valleys – far below, densely populated, with bulky blue-hazy ranges beyond. Then suddenly, high among superb unplanted mountains, I found myself over the ‘border’; there was no roadblock, perhaps because this area is so remote. Here shacks crowded the steep slopes and the atmosphere was distinctly unwelcoming, as predicted by APLA. Pushing Lear up one long hill I felt quite vulnerable as young men scowled speculatively at the panniers. In this sort of terrain a cyclist does not have the advantage of speed; turning to freewheel away from any difficulty would simply take me back to the base of an equally steep hill. I was halfway up when three youths began to shout at me aggressively – a nasty moment. But then an elder with an air of authority emerged from his neat little bungalow and silently shook hands (he spoke no English) before escorting me to the edge of the settlement. From there the track dived into a boulder-strewn, uninhabited valley.

The Eastern Cape is hilly enough but Natal is outrageously hilly; here is no such thing as a short climb or a gentle slope. On the main roads wayside notices warn that the next hill is five or six miles long with a gradient requiring trucks to take Special Precautions.

What must the first British settlers have made of this terrain when they arrived by the boatload between 1849 and 1851? But soon they were flourishing and marvelling at Natal’s fertility: lush grass growing five feet high, an abundance of free building timber in the kloofs, soil suitable for growing sugar-cane, cotton, tobacco, indigo and yielding two crops a year. All that plus a climate they incredulously described as ‘perpetual summer’ – and thousands of dispossessed ‘Kaffirs’ reduced to working for a pittance. (In 1848 five ‘native locations’ had been demarcated on land ‘unsuitable for European occupation’.) By 1853, families who had been starving in Britain a few years earlier were living in relative comfort, many killing their own mutton – the ultimate criterion of prosperity.

On this Sunday afternoon Ixopo (to pronounce it correctly you must make a choking sound) was moribund. A pleasant little town, its suburbs are even leafier than the norm, its homes and gardens spacious and English-looking. The bigger hotel is closed. The other, also big, has recently been bought by a cheerful Indian with no hang-ups about selling alcohol at 4 p.m. on the Sabbath. Yet again I’m the only guest and in Ixopo even the bar-trade is feeble. But Mr Moosa (Billy to his friends) remains resolutely optimistic.

‘This time next year things will be better. By then we’ll all feel we’re simply South African. A historic change is coming, a psychological change. Even Natal will be better, even kwaZulu.’

I wonder … This province is blood-soaked like no other. Last weekend saw sixteen murders: a ‘normal’ statistic. Men, women, children and babies are routinely butchered, by the dozen. Weapons abound and intimidation is general. Fear, hate, suspicion, bitterness, grief and wild demoralizing rumours have corroded the black communities and to some extent infected everyone.

Later, Billy and I were joined by Rudi, a middle-aged Coloured friend of the Moosa family. Ixopo, he informed me, is the Zulu word for the sound cattle make when withdrawing hooves from mud. Rudi has white skin, grey-green eyes and crinkly light-brown hair. ‘Wearing a wig’ – he grinned – ‘I could’ve passed for white if I’d wanted to. But the way things were as I grew up, you’d be ashamed to be white.’

Billy then took charge of an elfin 3-year-old daughter while her mother Seetha, a primary-school teacher, made scrumptious samoosas in the kitchen from where she shouted comments at intervals.

As a building contractor, Rudi worries about the immediate future. ‘Everything is at a standstill, I’ve no work for my men. Hey, it’s tough! They can’t live on sunshine, I have them on half-pay. But after the elections business will improve all round. The ANC won’t be having any more scary revolutionary ideas. There’s no risk here of a mess like up north.’

‘We’re solid behind the ANC,’ called Seetha from the kitchen, ‘us and all our families – though living here we don’t say so. Only to foreigners!’

Billy nodded. ‘Now no one else can run the show – politically, I mean. And we have our white tribe to run the economy.’

Seetha brought us a mountain of samoosas and a packet of paper napkins. ‘As I see it,’ she said, ‘our only danger now is too many whites hating and distrusting Mr Mandela. We don’t, we can respect him.’

‘But let’s talk straight,’ said Rudi. ‘Most Indians and Coloureds are anti-black. It’s a gut thing. All the same, it’s not like white racism. We’re only anti-black in bulk – see what I mean? Doesn’t stop most of us having some good black friends – real friends. How many whites can honestly say they’ve a black friend, a real friend? Maybe a few up in the university world, but damn few!’

Richmond, 2 August

Miles of swift freewheeling took me down to the Josephine Bridge (who was Josephine?) across the Umkomaas, altitude 1,800 feet. The river is low, yet this lush narrow valley yields an abundance of fruits and vegetables all the year round.

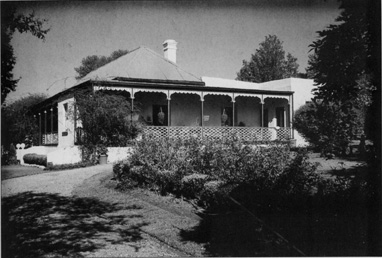

1. A late-nineteenth-century homestead in western Transvaal

2. The author and friend beside a traditional Boer open-air bread-oven

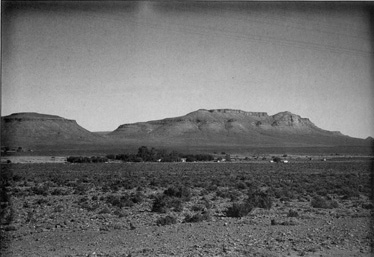

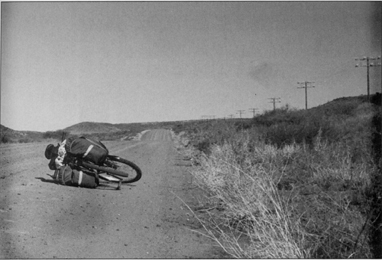

6. Lear in the middle of a dry river-bed in the Klein Karoo

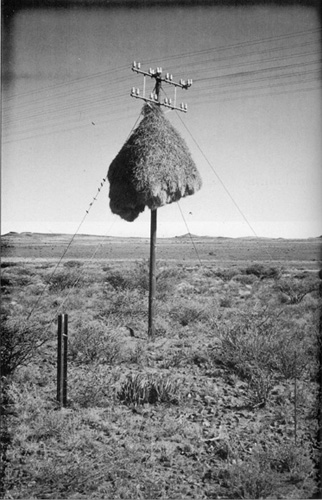

7. Weaver-birds’ nest on telephone pole

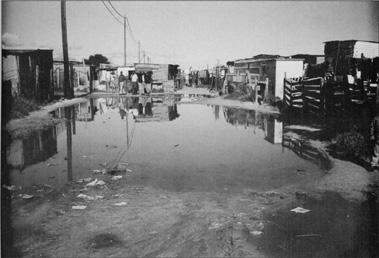

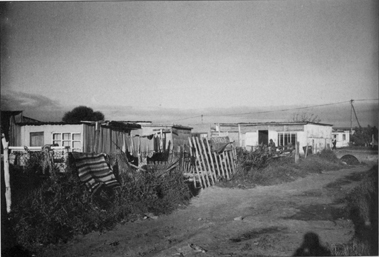

9. A Khayelitsha track flooded with sewage

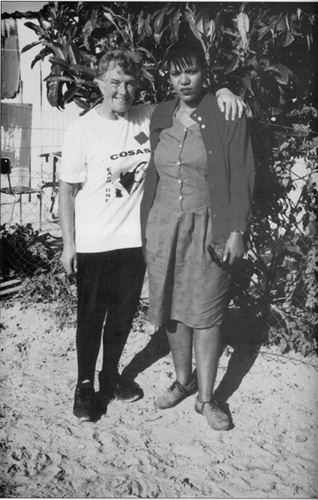

10. The author with a Khayelitsha Xhosa friend

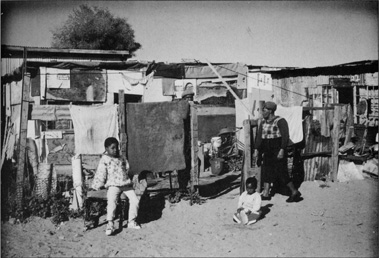

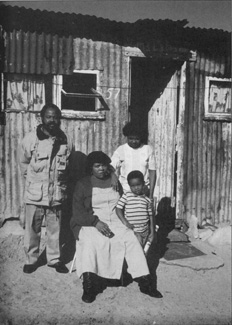

12. A Khayelitsha shack – upmarket

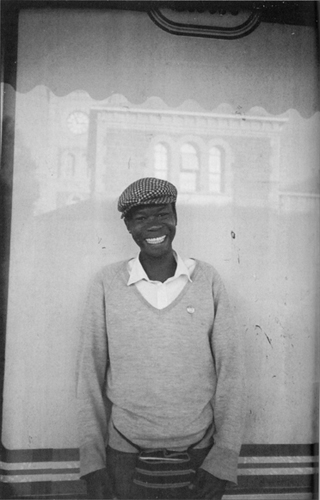

13. A Tswana helper in Kimberley

14. A Boer family graveyard in Western Cape

15. Lear with a young Boer admirer

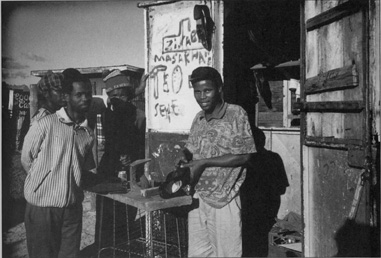

16. Local enterprise in Khayelitsha

18. The end of an era, 16 December 1994: the last Day of the Vow

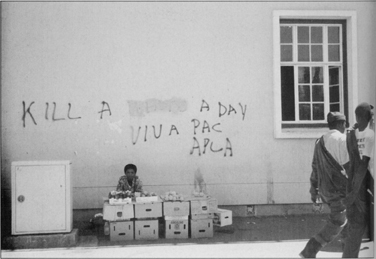

21. Gable-end in Umtata, December 1994

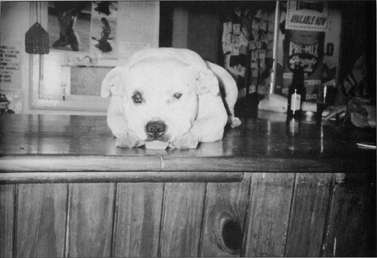

22. A bar attendant in Eastern Transvaal

24. A Zulu kraal between Melmoth and the coast

26. A friend in her family graveyard

27. A church serving the Anglican community in Griqualand East

29. Waiting for a taxi on Christmas Eve

Between there and Richmond (4,500 feet) my sweat-loss was sensational and on the outskirts of the town, in Websters Garden Stall, I drank two litres of amasi while a garrulous Anglo-Irishman chose his flowers, fruits and herbs. Long ago he left a mouldering Big House in Co. Cork and he has done well for himself in Natal. He excoriated the media. They report local black-on-black violence as happening in Richmond. It’s not happening in Richmond, it’s happening in Richmond’s townships. But the media can’t spell those names so they say ‘Richmond’. Consequently, property prices have halved and the two hotels have closed. Then there’s the drought. When they can’t cultivate, farmers find it’s best to go on long holidays to cheap Mauritius instead of staying in expensive South Africa. Many have sold their livestock and are giving all their water to the orange orchards. But the ’93 crop is dwarfed – unsellable. This victim of drought has just returned from a three-month holiday on Mauritius.

Beyond Websters I noticed a signpost to Byrne, a nearby village named after J. C. Byrne who in his lifetime was loathed by the hapless emigrants he cheated with such ease. Mr Byrne, operating from a smart London office, was among the many con-men who planned large-scale emigrations to Natal for their own profit.

During 1850 Natal – hitherto virtually unknown in Britain – suddenly became the fashionable colony. Some ‘independent’ emigrants, travelling cabin class, brought agricultural implements and a few farm animals. But most early settlers were destitute labourers who eagerly took advantage of such schemes as the Earl of Egremont’s Petworth Emigration Society. When the Duke of Buccleuch dispatched a shipload of surplus tenants they settled around Richmond. Numerous noble lords were only too pleased to get rid of their ‘distressed tenantry’ by paying £10 per head for fares and outfits consisting of clothing for two years. Also, as Britain was then in a panic about overpopulation causing ‘unrest’, the Poor Law allowed parishes to assist emigrants from the rates. Quite often, assistance became compulsion. Imprisoned felons’ families being dependent on the rates, many thieves and foot-pads were offered a choice: conviction or emigration.

Richmond’s tree-lined main street (Shepstone Street – no Voortrekkers here please!) proves how quickly the settlers recreated England. Natal’s first Anglican church was built here in 1856 and its rectory stands on the site of Natal’s first girls’ school (1869). Country crafts are now on sale where James Hacklands was making wagons by 1862. The court house began to dispense British justice in 1865. The Freemasons Lodge opened in 1884 (it seems the apostrophe had already fallen into disuse locally) and in 1897 came the railway station, at the end of a branch line from Pietermaritzburg.

Along Chilley Street you can smell the chillis. The Indian colony took root in the late 1860s and has been quietly flourishing ever since; Billy and Seetha were both born here. Can there really – I wondered, looking at the shops – be so many Patels in South Africa? Or has ‘Patel’ been adopted in lieu of names too long and unwieldy for settler tongues? I was seeking a Weekly Mail, nowhere to be found since I left Cape Town. By now the national media’s morbid navel-gazing has completely cut me off from the rest of the world; the only widely available global news concerns either sport – chiefly rugby and cricket, soccer is the blacks’ game – or the British Royal Family. The latter fixation defeats me; why should South Africans – including Afrikaners – be so riveted by the minutiae of royal deeds and misdeeds?

Mr A. P. Patel sells the Weekly Mail and Mrs Patel, remarking that I looked tired – I felt humidity exhausted – invited me into a back room for cinnamon tea and home-made sweetmeats. She had heard all about me from Seetha; one doesn’t travel quite anonymously through rural South Africa.

Richmond’s motel is closed but was bought a few weeks ago by a young English-speaking couple who have just reopened the bar and offered me a free bed in a garden shed. At the bar sat four Afrikaner SAP officers, unwinding after a stressful foray into a township. They competed to stand me beers and for my entertainment swapped the latest jokes – for example, ‘How many poles does it take to kill a Hani?’ Then they recalled various horrors in which they or their friends have been involved. Like the slaughter of eighteen Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) supporters in nearby kwaShange. And the night an important Zulu chief was assassinated outside his Pietermaritzburg home – the very same night an equally important chief and two of his followers were shot dead in northern Natal. On one of the worst nights, twenty-three were killed in Richmond. Soon after, two women were hacked to death with pangas in a local IFP leader’s house. This led to nineteen being arrested, including a member of the SADF. When an IFP member talked aloud about having proof of heavy white involvement in all this violence, he was shot dead next day – the very day Chief Ndlovu, known to be working hard for peace in the Richmond area, was assassinated near Ixopo. By now hundreds – no, thousands! – have joined both the ANC and the IFP in an effort to protect themselves.

The truth’s elusiveness compounds the terror aroused by the present crisis. It is impossible to establish the facts about any crime or to distinguish information from disinformation. Even in those rare cases when impartial Peace Monitor witnesses are present, they can observe only a fragment of the action and have little hope of obtaining reliable evidence from either side about motives, provocations, methods, consequences. This opacity is unnerving for the mass of politically uninvolved township dwellers – helpless victims of divisive rumours, accusations, denials and reprisals.

My kind hostess brought me, unasked, a large plate of boerewors and chips. As I ate, a fifth SAP officer joined us, an English-speaker in his early twenties. Soon Charlie was explaining, ‘My background is liberal – DP parents – and at school I used to stand up for blacks when that was risky. I’d notions about helping to reform the police. Now I hate blacks. After seeing how they treat each other, I hate them all. Last week only a few hundred came to an ANC demo in the town centre so the bully-boys toured the townships. Three hours later we’d 3,000 to control! Richmond’s two townships, Magoda and Pateni, had 30,000 blacks. Now there’s less than 15,000, most ANC have fled to the Rand or the Cape.’

George arrived next, in a Mercedes, the 24-year-old son of one of those hard-hit local farmers. Three years ago he was appointed manager of a large sawmill and he reported a recent ‘sensible’ SAPPI directive to all managers: ‘Employ only whites in the important jobs to keep production up.’ He reckons he’s sorted out all that subversive trade-union nonsense. ‘I told them, “If you put your trade-union subscription into the bank instead, you’ll soon have something to show for it. Why should you pay for a fine car for some trade-union dictator? Soon the bank will give you more money than you’ll ever get fighting with your employers.” It’s like always with blacks, you’ve got to think for them …’

Last year George heard the shots when his uncle was being murdered in his garage after ‘they’ had pillaged the house. ‘He wasn’t even trying to catch the bastards, he’d just driven in, they killed him for fun – or spite or something …’

It is hard to cope with South Africa’s relentless daily death-toll. Yet an extraordinary feature of this transition period is the overall normality of everyday life from the traveller’s point of view – while for the majority of citizens law and order is rapidly breaking down.

Pietermaritzburg, 3 August

Leaving Richmond at dawn, I wondered how the new South Africa will change the town. Surely it cannot continue to look as though neatly excised from Victorian England, carefully packaged and shipped to Natal.

Soon I had the Sugar Hill Racing Stable on my right and the Baynesfield Estate on my left. This estate was established in 1863 by Joseph Baynes, on 24,000 of the region’s most fertile acres; Mr Baynes, we gather, travelled cabin class. Next came miles of canefields and dairy pastures and then, near Pietermaritzburg, I passed thousands of shacks crowded on a wide mountainside which may or may not be fertile – there is no space left for cultivation. Speeding down the final slope – Natal’s capital lies in a hollow surrounded by high wooded hills – I noted a penumbra of pollution. Yet cities do have their compensations, like the Africana second-hand bookshop, my first halt. There I lost all self-control and a large parcel of rare vols is now on its way to Ireland.

I’m staying here with Glynis and Steve Bach, first met in Vosburg – staying only two nights because my return flight is booked for 17 August and I plan to return to Natal next April.

The same, 9 August

The fourth of August 1993 is a date I shall never forget. Early that morning I heard deeply distressing news from home and for the first time – being in a state of shock – neglected adequately to guard Lear. Two hours later he was stolen from my friends’ back garden.

Two black workmen in an adjacent garden witnessed the theft. When they questioned the intruder he claimed Steve owed him money but had refused to pay so he was taking Lear instead. The workmen must have known this was nonsense but they said no more. Were they afraid lest the thief might pull a gun? Or did they feel some sympathy for his enterprise?

Everything possible has been done to retrieve Lear but I never had any hope. At Steve’s insistence, a dim-witted Coloured police officer came that evening to take a statement. However, it would at present be unreasonable to expect the SAP to exert themselves in pursuit of a cycle thief. I offered a R500 reward – NO QUESTIONS ASKED – on the front page of the Natal Witness, this being the local price of a new mountain-bike. To publicize my loss the Witness also ran a half-page interview complete with a pathetic photograph; I didn’t have to feign looking stricken. The SABC did a long radio interview, broadcast countrywide. The local Zulu-language radio station gave a detailed description of Lear (but how easy it is to change a bicycle’s appearance!) with a passionate plea for his return and much emphasis on the reward. The local ANC offices displayed enlarged photographs of Lear accompanied by further passionate pleas. All, predictably, to no avail.

It is ironical that after months of dodging the sort of publicity likely to attend a female sexagenarian’s bicycle tour of South Africa in 1993, that journey has had to end under the spotlight. In consequence, some of my readers have surfaced and a new friend has nobly offered to lend me her bicycle – a precious machine, so I am touched and flattered. But now I lack heart (and time) for the last lap to Jo’burg. Tomorrow, Margaret and Jennifer are driving down to collect me; Margaret had already planned this trip to visit an aunt in Greys Hospital.

I am absurdly upset. On the practical level a bicycle is just a machine, an inanimate object easily replaced. But not so on the emotional level. To me Lear was a friend, my only companion on quite a long journey that started in Nairobi. I feel utterly desolate without him. (What would a shrink make of this admission?) One could argue – I have to try to make excuses – that a bicycle is not, after all, ‘just a machine’ as is a motor car. The cyclist and the bicycle form a team; they work together as the motorist and motor car do not. Perhaps other cyclists exist, somewhere out there, who can understand this. Or perhaps not. Maybe I’m uniquely dotty.

Now I must count my blessings. In fact only one is visible at the moment: that this journal was not stolen. It might have been, as it lives in a pannier-bag. But having rummaged through both panniers and found nothing of value to him, the thief ripped them off, no doubt fearing they might arouse suspicion (obvious ‘tourist property’) as he sped away. The only balm on my wound is the certainty that he needs Lear, in material terms, more than I do. A similar theft at home would have enraged me: you can’t feel enraged in South Africa when a black steals from a white.

In the air over the Transvaal, 17 August

However little they may deserve it, the whites do at present arouse sympathy – emotional earthquake victims, their whole world collapsing, fear of bloody chaos a dark shadow, incomprehension of blacks distorting their view of the future. An incomprehension nonetheless heartbreaking for being inevitable, in South Africa – and of course vehemently denied. How often I’ve had to listen to both Afrikaners and English-speakers explaining why they understand blacks so very well – because as children they had no other playmates and went off to boarding school speaking better Sotho/Xhosa/Zulu than Afrikaans or English. The implied insult to African culture is breathtaking. Imagine a Chinese child growing up to the age of 10 on some remote nineteenth-century European farm, playing only with the children of illiterate, impoverished labourers and on the basis of that experience claiming as an adult that he understood Europeans very well. People would laugh at his stupid arrogance.

Why am I already eagerly looking forward to my return on 1 April ’94? I seem to be entangled in a love-hate relationship with South Africa, a baffling emotional involvement with its variegated tribes and their tragic problems. Now I care about what happens to them – all of them – to an extent I would not have believed possible six months ago.