ROMANIAN NATIONALISM in the nineteenth century evolved in tandem with the increasing economic role of Jews in the country. In February 1866, Romanian Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza was forced to abdicate, and in May of that year Carol de Hohenzollern-Siegmaringen (later King Carol I, 1866–1914) assumed the throne. Two months later a new national constitution was adopted; Article 7 of this document denied Romanian Jews their political emancipation—a situation that would prevail until after World War I. Romanian Jews thus became stateless, heightening their vulnerability to economic and political discrimination. The motivating resentment against the Jews came both from the boyars, or gentry, and from the new bourgeoisie, who had recently begun to play a political role in the nation’s affairs. As long as Jews worked as go-betweens—tax collectors, distributors of manufactured goods, and salesmen of spirits for whose production the boyars held the monopoly—they were allowed a measure of rights. But as soon as they showed a desire to integrate, to gain civil and political rights, they were deemed a “social peril,” the “plague of the countryside,” and similar epithets.

Jews had long been active in Romania in a wide range of crafts. Their economic competition stimulated the new Christian bourgeoisie to violent opposition and to the advocacy of measures “restricting” Jews in favor of “national labor.” Meanwhile, too little land consigned the peasants to lives of misery. Unable to resolve the severe agrarian problem and willing to pander to the nationalist feelings of Christian craftspeople and merchants, the government sought to divert its frustration and anger onto the Jews.1 Although Article 44 of the 1878 Congress of Berlin had linked international recognition of Romanian independence to the granting of equal political and civil rights to the Jews, the government soon abandoned this aim, substituting for full emancipation a procedure to grant “naturalization” only on an individual basis. From that time well into the twentieth century, Romanian writers expressed hostility toward Article 44.

After World War I, three regions were returned to Romania as agreed upon in the Treaty of Versailles: Bessarabia from Russia, and Bukovina and Transylvania from Austro-Hungary. Political leaders were enthralled with the reunification of historically Romanian provinces under the national flag. Simultaneously, however, that same leadership demonstrated a growing reluctance to grant civil rights to minority groups. Despite strong pressure from Western powers, not until 1923 did Jews in Romania win legal equality.

After 1929, “the Jewish question” acquired an increasingly mass character, with recurrent economic crises serving as background. Anti-Semitic activities were not solely the work of radical organizations. From a desire to restrict “Jewish capital” (partly the consequence of perceived electoral necessities), both the National Liberal party and the National Peasant party adopted anti-Semitic slogans. Mainstream and fascist parties alike exploited anti-Semitic agitation aimed at the lower-middle class, among whom they nurtured the idea of climbing the social ladder and who blamed “Jewish competition” for thwarting their efforts to do so. King Carol II’s royal dictatorship (1930–1940) substantially intensified anti-Semitism and economic polarization (spectacular wealth for the few and acute privation for the masses)—all the more reason for the masses to adopt anti-Semitic rhetoric and to make anti-Semitic gestures. As a Romanian scholar observed:

Anti-Semitic propaganda that the dictatorship’s men were unscrupulously conducting together with agitators on the far right every day, every hour, fueled the hatred, the resentment, and the appetite of the petty bourgeoisie. . . . Unscrupulousness . . . and ignorance were instrumental in falsifying reality and transforming social problems, especially those of the lower-middle classes, into a racist issue. The Romanian and Jewish upper classes also benefited [from the direction of resentment at the more visible] Jewish lower-middle class that comprised the impoverished population of Moldavian towns and cities [and] suffered deprivations still greater than those of the Romanian population. [It was these people who] had to endure all the humiliations and brutality of relentless persecution. But the underlying truth remained hidden behind the rantings of those who, year in and year out, preached “racial” hatred and pogroms.2

In brief, economic problems underscored the rise of Romanian anti-Semitism after 1929, amplifying the political and cultural manifestations of nineteenth-century attitudes toward Jews. External factors also contributed: the influence of theoreticians of anti-Semitism such as Edouard Drumont, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Charles Maurras, and Alfred Rosenberg, as well as the tolerance of Western governments toward the openly anti-Semitic joint regime of Octavian Goga (a government official in various positions through 1938) and Alexandru C. Cuza (head of the National Christian party).

Before World War II, the Jews of Romania were organized into local communities that oversaw religious life, education, and philanthropy; Romanian law countenanced the existence of Jewish federations. Such a federation existed in Regat (“Old Romania” or the “Old Kingdom” of Romania in its pre–World War I borders) with its own chief rabbi. Regat contained both Ashkenazi and Sephardic communities, most of the Sephardim being concentrated in Bucharest. The Ashkenazim were divided between traditional and liberal blocs. There also were ultra-Orthodox communities in the city of Sighetul Marmaţiei (Maramureş District) and in Sadagura (in Bukovina). Jewish holidays such as Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Pesach (Passover), and Succoth generally were strictly observed in the smaller Jewish communities, but in the larger cities Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur were increasingly the only holidays observed by most Jews.

Virtually every sizable Jewish community had a synagogue, some sort of cultural and administrative center, a communal school, and a home for the elderly. There were several Jewish hospitals: in Bucharest, Iaşi, and Cernăuţi. Two major organizations expressed the interests of this population: the Union of Romanian Jews (Uniunea Evreilor Romani, or UER) and the Jewish party (Partidul Evreiesc). Wilhelm Filderman, who headed the former, fought for the civil rights of Romanian Jews; the Jewish party was a Zionist organization led by Theodor Fisher, Josef Fisher, Sami Singer, and Mişu Weissman. Numerous B’nai B’rith lodges and other Zionist organizations were to be found throughout the country.

Although the standard of living among Romanian Jews in the 1920s was higher than that of Polish Jews, many were virtual paupers. In Bessarabia and Regat cultural assimilation was quite pronounced. For the most part the Jews read Romanian newspapers, although in Bessarabia the older generation spoke Yiddish. It was also spoken in Moldavia but not in Walachia. Most Jews in Transylvania shared affinities with Hungarian culture.

In 1930, of 756,930 Jews in Romania, 318,000 derived their income from commercial enterprise, including 157,000 from trade and credit, 106,000 from manufacture or the crafts (twice the rate of the Romanian population), and 13,000 from agriculture. Nine thousand were self-employed, and eight thousand worked in communications or transportation. Romania could claim some very wealthy Jewish families, such as the Auschnitts, who owned steel factories and iron mines. Jewish banks, such as Marmorosh Blanc & Company, Lobl Bercowitz & Son, Banca Moldovei, and Banca de Credit Român, played an imposing role in the economy. Except for the last of these, however, all went bankrupt during the depression of the 1930s.

Jews constituted 40 to 50 percent of the urban population in Bessarabia and Moldavia. Fully half the population of Iaşi, the original capital of Moldavia, was Jewish. The 1930 census shows that Jews made up the following percentages of the total population by region:

| Region | Percentage3 |

| Bessarabia | 7.2 |

| Bukovina | 10.8 |

| Dobruja | 0.5 |

| Moldavia | 6.5 |

| Muntenia | 2.1 |

| Oltenia | 0.2 |

| Transylvania | 10.0 |

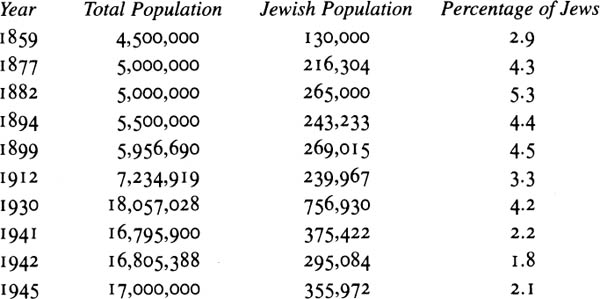

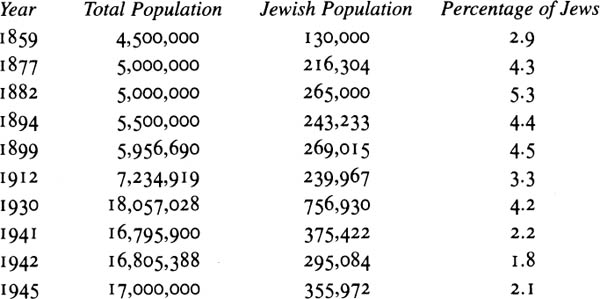

Civil liberties that Jews had worked for generations to acquire were seriously undermined by the Goga-Cuza government’s anti-Semitic laws of 1938, which, inspired by Germany’s Nuremberg Laws, deprived at least 200,000 Jews of their civil rights. Ion Antonescu’s governments of 1940 and 1941 abolished the rights of the remaining Jews. The war and the pattern of Nazi anti-Semitic policy gave the Romanian “Conducator” (or ruler) the opportunity for a radical “resolution” of the Jewish question in Romania. The numerical aspect of that “question” and how it was answered may be traced in the percentages of Jews as part of the Romanian population from the middle of the nineteenth century until the end of World War II:4

The dramatic decline in the number of Romanian Jews in 1941 and 1942 is obvious. Yet in a memorandum distributed by the Romanian delegation to the 1946 Paris Peace Conference, only 1,528 Jews were said to have died in Transnistria and 3,750 inside Romania (probably Regat only).5 Raul Hilberg, however, has concluded that 270,000 Jews died in Romania, a figure that seems to be a reasonable approximation.6 (This figure does not, however, include 135,000 Transylvanian Jews killed after deportation by the Hungarian administration of northern Transylvania to Nazi concentration camps or the sizable indigenous population living in Transnistria, the area between the Dniester and Bug Rivers, which fell to Romania during the war.)

What indeed was the fate of the Jews who lived under Romanian administration in Regat, Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Transnistria during World War II? How many Jewish victims lived, and in many cases died, under the Romanian administration during those years? To what extent did the German and Romanian administrations cooperate in the destruction of Romanian Jews? And finally, how can one explain the survival of half the Romanian Jewish population at the end of that war?

On December 26, 1942, 196 Moldavian and Walachian Jewish forced laborers in Transnistria were loaded into cattle cars for a nineteen-day journey that took them from Alexandrovka to Bogdanovka. They traveled without food or water in temperatures dropping to forty degrees below zero. Eleven of them died during the trip. Upon arrival on January 14, 1943, they were piled into a pigsty, where they tried to protect themselves from the cold with straw. “The straw is for the pigs, not for the Jidani [kikes],” the farm administrator bellowed at them.

This small-scale tragedy is only one of thousands revealed by Romanian wartime documents and the testimonies of witnesses and survivors. At least 250,000 Romanian and Ukrainian Jews perished under the Romanian fascist administration. Transnistria, the part of occupied Ukraine under Romanian administration, served Romania as a gigantic killing field for Jews. Yet the majority of 375,000 survived to the war’s end. The question is whether Romania’s wartime dictator, Marshal Ion Antonescu, was a murderer or a savior of Jews during the Holocaust.

A post-Communist Romania has recorded a mixed attitude to a history swept under the carpet by the Communists and officially forgotten for decades. On the one hand, upon reaching Slobozia or Piatra-Neamţ, today’s traveler may find himself greeted by a statue of Antonescu in a town square; some of these memorials were indeed dedicated with considerable fanfare and the participation of government officials. Many streets have been named after Antonescu. In Oradea one of the city’s most important synagogues stands on such a thoroughfare. Yet the country’s current president, Emil Constantinescu, has publicly acknowledged Romania’s responsibility in the Holocaust, and recently the Ministry of Education has mandated the teaching of the Holocaust in Romanian schools.

The movement to rehabilitate Antonescu may be fueled by the energy of a limited number of nostalgics, but its roots stretch deep into Romania’s history. Soon after World War II, the Communists began to impose their own criteria for the writing—or rather, rewriting—of Romania’s past. Initially exploited as a propaganda tool for use against their political enemies, the saga of the extermination of the Romanian Jews soon disappeared from the newspapers and from scholarship and classroom instruction; later, study of the fascist period fell victim to a propaganda requiring numerous omissions and distortions. The 1960s in particular saw the emergence of an overtly nationalistic and xenophobic tendency in Romanian historiography, giving rise to a new official scholarship that left out the destruction of a large part of Romanian Jewry during World War II.

Openly revisionist books appeared during the 1970s, diminishing the number of Jewish or Gypsy victims and promoting the notion that the Romanian government was in no way responsible for the killings. Instead, they were implicitly or explicitly attributed only to “the Germans and Hungarians.” Communist revisionist historians suggested that Romania had not—as other countries had—cooperated with the extermination plans of the Nazi regime: an alleged national resistance reflected the Romanian people’s militant humanism, a humanism that had prevented in Romania the monstrous crimes carried out by Germany and other of its allies. Outright lies, such as the assertion that the Romanian government had not surrendered a single human life to the Germans, found their way into the works of Romanian historians.

After the fall of Nicolae Ceausescu, Romania’s president from 1974 to 1989, revisionist writings multiplied. Many historians characterized Antonescu’s regime as only “moderately anti-Semitic.” Some even declared that the fascist regime had approached the solution of “the Jewish question” only by encouraging emigration. After Ceausescu’s departure a heavily anti-Semitic and xenophobic movement grew in Romania, generated by an alliance of extremist political parties and drawing upon the enthusiasm of unreformed elements from the former Securitate, the secret police of the Communist regime. The aim of these groups has been to isolate Romania, end political and economic reform, and establish their own control over the country. They have sought to identify foreigners in general, ethnic minorities in particular, and especially Jews as responsible for all the difficulties Romania faces. The deep roots of the Romanian anti-Semitic tradition have brought to this campaign followers from the mainstream parties too, both those in power and those in the opposition. From the pseudosocialist left to the alleged conservative right, numerous politicians have supported the rehabilitation of Antonescu, citing (as pretext) his liberation in 1941 of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, which had been occupied by the Soviets in 1940. How could this liberation have been accomplished except through the alliance with Nazi Germany, and why would one hold a few abuses of the Jews (perhaps regrettable but understandable, considering widespread “Jewish assistance to the Soviets”) against the accomplishments of such a national hero?

Extremist politicians have not been the only ones seeking to glorify Antonescu. Representatives of the Romanian mainstream intelligentsia have also participated indirectly in his post-1989 rehabilitation. Professor Mihai Zamfir, who became Romania’s ambassador to Portugal, compared to “a hero” France’s Maurice Papon, the onetime Vichy deputy prefect of Gironde who was condemned for the deportation of fifteen hundred Jews. Romania Literara, a leading literary weekly, accused Jews of conspiring to cover up the crimes of communism and of exploiting the Holocaust as a way of claiming a monopoly on suffering. Against this majority, the distinguished professor George Voicu, to take only one example of a quite different tendency, has struggled with the “irrepressible anti-democratic, xenophobic, anti-Semitic temptations” of the Romanian intelligentsia. Voicu wrote that “as long as Romanian intellectuals continue to see [anti-Semitism and the Holocaust] as a secondary, irrelevant, embarrassing . . . topic, or even more disturbingly, as an antinational or false issue, . . . Romania will be condemned to remain a peripheral, exotic state, [largely impervious] to the values of European and universal culture.”7

For those who follow post-Communist politics, Romania’s attempt to rehabilitate a World War II fascist government comes as no surprise. Chauvinism, revisionism, and attempts to rehabilitate war criminals are characteristic of most Eastern European countries. Yet the case of Romania is the most egregious: nowhere else in Europe has a mass murderer, Adolf Hitler’s faithful ally until the very end, a man who once declared war on the United States, been honored as a national hero, inspired the erection of public monuments, and had streets named for him.