1: A New Newspaper Model

“The American newspaper is distinctly ahead of its English contemporaries,” announced William Thomas Stead, one of the most celebrated newspapermen in England, in 1901. “To begin with, there is more of it, more news, more advertisements, more paper, more print,” he explained. “Hence the busiest people in the world, who have less time for deliberate reading than any race, buy regularly morning and evening more printed matter than would fill a New Testament, and on Sundays would consider themselves defrauded if they did not have a bale of printed matter delivered at their doors almost equal in bulk to a family Bible.”1 The sheer quantity of news necessitated some sort of organizing system. Stead analyzed and praised one American solution, the large headline—or as he called it, the “scare-head.” Scare-heads made reading more efficient, allowing people to glean information in only a few seconds and to choose the articles they wanted to read in full. But headlines also, thought Stead, made the news more appealing. “The scare-head is like the display in the show window in which the tradesman sets out his wares,” he wrote. “Good journalism consists much more in the proper labelling and displaying of your goods than in the writing of leading articles. The intrinsic value of news is a quality which does not depend upon the editor, but the method of display.”2

Stead had encountered a new newspaper business model, in full flower in turn-of-the-century American cities. Faster presses suddenly made it possible to print Bible-sized papers, and revenue from advertising kept those papers affordable. For the first time, publishers could sell their product for next to nothing yet still reap healthy profits. Under this system, urban daily newspapers cut their prices, expanded their offerings, and grew their circulations. Stead was witnessing newspapers’ transformations into true mass media whose influence reached across thousands or even millions of readers’ lives.

To turn out such large newspapers, publishers had to grow their companies. They constructed new buildings, hired large corps of news workers, and purchased massive machines. Newspapers—as organizations as well as objects—became emblems of the modern era, whose profitability, efficiency, and sheer size garnered popular attention and outright awe. Stead noticed that, as newspapers grew, they provided more information than anyone could actually use; they made the “busiest people in the world” even busier. Newspapers contributed to urban information overload; they circulated pages full of clashing messages and eye-catching images and filled city streets with newsboys’ loud pitches and reporters’ hard-hitting questions.

Stead chose an apt metaphor, the shop window, for newspapers had indeed become more commercial products than ever before. Stead described the articles themselves as products to be consumed, each one vying to be chosen and read. Newspapers became shop windows more literally, when editors ran elaborate ads, crafted features that focused readers’ attention on consumer topics, and persuaded local merchants to advertise. By the turn of the century, publishers regarded even their own audiences as products to be sold. Publishers boasted about the numbers, the wealth, and the spending habits of their readers and then sold the attention of those readers to advertisers.

The huge new papers of the turn of the century came in for both praise and criticism, as Stead’s defense suggests. But they were unqualified successes. Fast, lucrative, efficient, and abundant, newspapers became beacons of a new era in urban America. They also entwined public dialogue with commerce so thoroughly that readers could not disentangle the two.

“More news, more advertisements, more paper, more print”

When a man or woman in 1880 paid two cents for the daily paper, he or she walked away with four pages absolutely crammed with information. Printers chose small type for the titles, smaller type for news, and minuscule type for the classified ads. Many printers dispensed with titles altogether, printing only the broadest of headings: “The Latest News” or “Local Affairs.” Wherever extra space remained, printers tucked in one more tidbit—an anecdote, a statistic, or an advertisement.

These papers were products of nineteenth-century technology. Rags, the raw material for newsprint at the time, yielded sturdy and long-lasting paper but were relatively expensive and in constant short supply. Editors had to perpetually weigh whether information was worth the cost of the paper it would be printed on. The painstaking printing process also forced publishers to keep their papers to a modest size. “The circulation of a daily newspaper was imperatively limited by the number of pulls one pair of arms could give a Washington press,” explained Whitelaw Reid, editor of the New York Tribune. A large and successful paper might circulate only four hundred copies.3

Nineteenth-century publishers relied on advertisements as well as subscriptions for revenue, and assumed ad printing to be part of their job. Indeed, papers in dozens of different cities took the name Commercial Advertiser and crowded their entire front pages with ads. Advertising, however, still carried with it a shady reputation. In a world where people made most of their purchases and sought most services from people they knew, readers treated items advertised in the paper with caution. Why would they buy something of unknown origin? Why would they take advice on what to buy from a stranger? Advertisers often did have something to conceal, whether touting the benefits of a “health tonic” or trying to sell an arid patch of farmland.4 So most urban daily newspapers kept advertisers to certain parameters, requiring that they use extremely small typeface, insisting that they keep their ad the width of a single column, and permitting them to illustrate only with a tiny symbol indicating the type of good or service offered. This formula minimized the space that each individual ad took up—important in the era of expensive newsprint—and kept advertisements from overshadowing the news. And crucially, it was the vertical lines between columns, when placed on the printing frame, that physically held the type together. Without the column marker wedged between, the letters simply fell out.5

The newspapers that resulted from these conventions are almost impenetrable to the modern eye. They offer no pictures, large headlines, or boxed advertisements to break up the monotony of tiny text. To the nineteenth-century reader, though, it did not much matter what the paper looked like. If a man had an hour to spare and a paper in hand, he would likely start at the beginning and work his way through the whole issue. In the sea of text, he would discover spots of relevant, entertaining, or absorbing news. He might laugh at a prickly letter to the editor, note that a neighbor had been admitted to the hospital, and pay special attention to news from his parents’ home country. Perhaps he balked in disagreement at some of the editorials—but more likely he nodded in approval as he read, for he knew which paper spoke for the city’s Democrats or its Republicans, and he bought the opinion he wanted to hear.

Other readers might pick up a paper in a tavern after work. They, too, read through from start to finish, and then perhaps discussed the increase in railroad rates with an acquaintance at the bar. Still others brought the paper to work with them. Cigar rollers or seamstresses took turns reading aloud to one another or allotted the task to the best reader among them. The reader might stop at a description of a greedy landlord’s trial and relay her own similar troubles, linger over an intriguing personal ad, or weigh out loud the reasons for and against immigration restrictions. Families, too, might take the news this way, in a post-supper circle around a father or daughter reading aloud. Each member could tune in and out, and sometimes comment, as they smoked, sewed, or washed the dishes.6

This entire mode of reading the news would disappear when cheap newsprint rendered the four- or eight-page newspaper a thing of the past. Manufacturers gradually perfected a new process that used wood pulp rather than rags as raw material, and the newspaper business developed a voracious appetite for it—in 1897 the New York World went through a spruce forest four times the size of Central Park.7 Over the course of the 1890s, the annual per capita consumption of newsprint rose from six to sixteen pounds, as daily papers grew fatter and fatter.8 Abundant supplies of newsprint also gave publishers far more freedom to experiment. They could use large and artistic typefaces, print expansive illustrations, and still charge the same price that they had for the old-fashioned four-page paper.

With cheap newsprint, editors could afford to print large papers; with fast presses, they could churn out enough of those larger papers to meet demand. Richard Hoe introduced his rotary press (fig. 1.1) in the 1840s, which spun off seamless reams rather than individually stamping out sheets. Over the following decades, several more inventions sped things up. Printers learned to cast molds, called stereotype plates (fig. 1.2), from hand-set type and then fit the plates to rotary presses. The Mergenthaler Company perfected the linotype machine, which allowed workers to type out newspaper columns rather than hand set them (fig. 1.3). Autoplate machines, developed around 1895, prepared images for Hoe presses in record time.9 Rotary newspaper presses grew larger and larger, until many papers housed mammoth double-decker machines that worked at staggering speed and volume. In 1905, the New York World’s presses could print 720,000 eight-page papers in a single hour.10 Only the largest and wealthiest newspaper offices purchased these giant presses at first. Once publishers had installed them, though, they often began to think more ambitiously about their readership, for a well-equipped printing room could meet any demand that advertising and circulation staff managed to drum up. And because Hoe presses could easily print, fold, and stack separate sections, they freed publishers to create sprawling, multipart papers.

1.1 Hoe Rotary Press at the Milwaukee Journal, 1912. This same technology was already in place at the biggest papers in the 1890s. Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-119169.

1.2 Stack of stereotype plates, New York Herald, 1920s. These half circles would then be fitted together into cylinders, to spin off sheets of paper in a rotary press. The word “stereotype,” invented to describe this technology, only later took on its metaphorical meaning. William Thompson Dewart Collection of Frank A. Munsey and New York Sun Papers, Image 90970d, New-York Historical Society.

1.3 Linotypists at the Milwaukee Journal, circa 1912. When the typist hit a letter key, that letter in metal type slid down the machine’s diagonal chute, where it aligned with and then fused to the other typed letters. Wisconsin Historical Society, WHS-119172.

Newspaper publishers and readers alike celebrated this new printing technology as a modern wonder. The New York Herald built glass panels into the lower level of its building on Thirty-Fourth Street in 1893, so that passersby could see the presses in action.11 The managing editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported to his boss, Joseph Pulitzer, after he opened the paper’s new printing plant: “As I write, there are at least 75 people in the country room watching the presses work, while there are crowds about the front of the building admiring the presses in operation.”12 When the Milwaukee Journal ordered eight linotype machines, a line of visitors shuffled through the composing room for two and a half hours to see how they worked.13 School children began to visit on field trips. When the New York World produced its first color supplement in 1898, it took the opportunity to show off the color press itself. An illustration showed visitors observing the press in action; the accompanying text described the machine’s parts and abilities in detail (plate 1). When readers visited a press or viewed a linotype machine, they showed their interest in not only the product but also the process of news. They wanted to understand the astounding technology that produced their daily paper and that also seemed to herald a new age of mechanical precision and speed.

Income from advertisements—alongside cheap paper and fast presses—enabled publishers to dramatically expand their papers. By the turn of the century, advertisements had lost much of the stigma that had led so many editors to give them only minimal space and attention. In cramped apartments, migrants no longer had the space or supplies to mill their own soap, grind their own flour, or even sew their own clothing. And unlike those in small towns or rural communities, city dwellers did not always have the option of sourcing goods from familiar faces. Other urbanites wished to live as they imagined their richer or more “American” neighbors did, and their aspirations could not be satisfied in their neighborhoods’ shops. Many urban Americans were ready to listen to anyone who could tell them what to buy and where to buy it.

In 1880, American companies spent thirty million dollars on advertising. By 1910, that number increased twentyfold to six hundred million dollars, a full 4 percent of the national income.14 New trade magazines like Printers’ Ink and the Advertising World counseled salesmen. Advertising agencies sprouted up in major cities, first advising their clients on where to place advertisements and, later, helping them craft effective pitches.15 “Fill the advertisement so full of hooks that the glancer is likely to get caught,” advised one expert in the field.16 Only this way would readers come across items that, until then, they perhaps had not known they needed.

Advertisers’ new eye-catching images and flamboyant text could not be made to fit within the old newspaper model—though some tried (fig. 1.4).17 Gradually, editors conceded more of what advertisers wanted, allowing them to spread out over a half or a full page. Once stereotypes and autoplates made it easier to print unconventional images or unusual typefaces, editors permitted illustrated, attention-grabbing ads.

1.4 Advertisers bent the rules by setting letters in eye-catching patterns, in this case forming small letters into large text. New York Sun, 11 March 1880, 4. Other strategies included printing a message one hundred times in a row, using capital letters to spell vertical messages through blocks of horizontal text, or constructing images (such as a Christmas tree) out of words.

Newspaper publishers gained some of their advertising savvy by watching their peers and competitors: monthly magazines. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, a handful of entrepreneurs launched magazines, such as Cosmopolitan, Munsey’s, McClure’s, and the Ladies’ Home Journal, that targeted a large and growing national middle class. These magazines offered highbrow literary fare, such as one might find in Harper’s or the Atlantic, but wove in more personal, practical features such as household advice and etiquette columns and more fanciful material such as travel stories and romantic fiction. The whole package sold for ten cents, or a dollar a year. These new monthlies proved a runaway success; by 1905, enough magazines sold each month to put four on the coffee table of every American household.18

Magazines demonstrated that advertisements, far from being unwanted distractions, could actually increase profits and attract readers. Instead of confining ads to a segregated space, magazine editors spread them over a whole issue. They offered advertisers prime space in the front pages, or gave them the full back cover, and charged them a correspondingly higher price. Magazines also helped merchants advertise by streamlining their ads’ typeface or adding illustrations.19 So beautiful and imaginative were magazine ads that readers regularly tore out their favorite ads before tossing away the magazine; one writer quipped that articles had become mere “space-fillers” between the ads.20

As newspaper publishers adopted these magazine strategies, they charged more for highly visible ad space and turned ads into part of newspapers’ appeal. This slowly changed the look and purpose of newspapers. By 1900, ads often took up more than half of the pages in daily papers. “If bulk alone is considered,” admitted circulation manager William Scott in 1915, “the title should be changed from ‘news’ paper to ‘ad’ paper.”21 Ads also remade newspapers’ operating budgets. Advertising revenue had provided 44 percent of periodicals’ total income in 1879; by 1909 it provided 60 percent.22

Relying so heavily on advertising money opened many new possibilities to newspaper publishers. Advertisements paid for larger papers, bigger presses, and more skilled staffs.23 But in relying on ad money, newspapers went from selling one product to selling two. They sold a newspaper to readers; they also sold their readers’ attention to advertisers. And advertisers wanted the attention of as many readers as possible.

Readers Become Customers

During the nineteenth century, many newspaper editors had carved out niche audiences within urban reading populations and contentedly catered to those loyal readers. But by the turn of the century, that strategy no longer worked. Many editors felt compelled—by expenses or by competition—to drum up new readers to please advertisers. New York City’s cutthroat newspaper business bred some of the era’s most innovative selling strategies, but editors in San Francisco, Saint Louis, Chicago, and a host of smaller cities experimented too, aggressively marketing themselves to readers. They hired bigger corps of reporters to provide more thorough and timely news. They drew readers in with scandals and stunts and kept them reading by promising something even better in the next issue. Editors sought out sectors of the city’s reading population that they had earlier ignored and created new content just for them. These new practices turned newspapers into a daily habit for all kinds of people and, for the first time, forged a truly mass audience.

Newspaper publishers began to think like advertisers, and developed schemes to get their product into the public eye. Where newspapers’ personalities had once surfaced in their editorial voice and opinion, publishers now crafted their papers into recognizable brands. Much like detergent companies and department stores, newspapers used slogans and packaging to distinguish themselves from the competition. When William Randolph Hearst bought the New York Journal in 1895, he dubbed it “A Modern Newspaper at a Modern Price.” The New York Times followed with “All the News That’s Fit to Print” in 1896, and the Chicago Tribune claimed first to be “The People’s Paper,” then “The World’s Greatest Newspaper” on its front page. Publishers adopted unique typefaces and mastheads, to give their papers distinctive looks.24

Nearly every major daily hired a circulation manager and set aside a budget for publicity.25 Publishers then plastered city surfaces with ads. They distributed color posters for news vendors to hang up and placed ads on streetcars.26 New York’s World constructed a sixty-foot-wide electric sign on the roof of a five-story building at Fifth Avenue and Twenty-Fifth Street to announce its circulation of over five million a week.27 Publishers had no qualms about infringing on competitors’ territories; they used each other’s pages to advertise.28 And whenever newspapers ran special features, they drummed up interest through previews, advertisements, and posters. The New York Journal, for example, pasted images from its upcoming Sunday comic strips on construction scaffoldings (fig. 1.5).

1.5 A New York Journal poster on scaffolding on Twenty-Third Street, 1896. The poster uses the Yellow Kid to advertise the paper’s color comic supplement. The men in the foreground are rag pickers; they suggest that the market for rags survived even after newspapers started using wood-pulp paper instead. Photograph by Alice Austen, courtesy of the Alice Austen House.

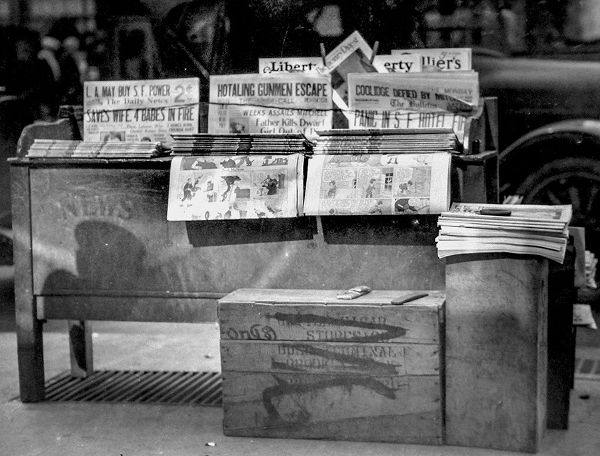

All of this newspaper advertising helped to build a new kind of city landscape, in which every surface communicated a message and every image called out for attention. City newsstands were riots of print; giant headlines shouted from stacks of newspapers and six-foot-long posters announced the day’s features.29 Newspapers’ flashing electric signs, which one onlooker described as “striking and almost startling to behold,” overwhelmed the buildings behind them and cast a glow on cities’ plazas and passersby.30 City landscapes—plastered with signs, saturated with leaflets, strewn with newspapers and magazines—gave the eye no calm place to rest.31

Newspapers’ in-person sales tactics, too, created a more stimulating and chaotic city. Circulation managers dispatched salesmen on house-to-house canvassing campaigns, offering subscriptions for twelve cents a week.32 They equipped the salesmen with scripts that listed dozens of selling points to rattle off, so that customers might agree to take a subscription out of sheer argumentative exhaustion.33 Much like posters and flashing signs, the hundreds of newsboys on city corners added to the quantity of stimuli in metropolitan life. In 1885 a New Orleans writer described a typical city newsboy, who “shocks nervous people by screaming like a steam whistle.”34 Boys yelled out headlines from the paper as impromptu advertisements, filling the streets with shrill announcements of fire, warfare, and murder. These sales methods succeeded in enlarging newspaper audiences; they also helped to create a new kind of market that could be harsh not only on competitors but also on consumers. “The reader does not seek the paper,” explained Don Seitz, business manager of the New York World; “the paper lets no possible reader escape.”35

Publicity campaigns could attract steady audiences only if newspapers then provided satisfying reading. So publishers did everything they could to print more and better news than their competitors. Publishers—especially those of sensational papers—hired the best reporters away from rivals, and they stationed these reporters all over the city.36 In 1907 a New York City journalist listed eleven places that the papers “watched constantly,” another fourteen that they watched “carefully but not continually,” and dozens that reporters checked in on at least once a day.37 Special reporters kept a finger on the pulse of each different urban scene, from cities’ charity bureaus to chambers of commerce, from harbors to labor unions. “A city is now ‘covered’ by a machine as fine and complicated as a rotary press,” explained reporter Will Irwin in 1911.38

Editors also outfitted their papers to “scoop” competitors as often as possible. Charles Dana, editor of the New York Sun, found that news of a fire added ten thousand readers, the results of a sports race added twenty-five thousand, and the outcome of a presidential election added eighty-two thousand readers.39 Any paper that scooped such events would thus profit handsomely. Editors provided a handful of reporters with the freedom and the funds to do whatever it took to get the freshest, juiciest bits of news.40 Some editors also paid any person who brought them an eyewitness account, and paid up to five times more if that witness promised not to share the news with any other paper. This instilled a habit in some city people of rushing to a newspaper office as soon as they had witnessed an accident or a crime.41 Printers, meanwhile, developed a mechanism called a “fudge” to insert breaking news into a paper even while the press was rolling. “If New York City Hall were to fall down,” predicted journalist John Given, “both the Evening Journal and the Evening World would, in all probability, have ‘fudge extras’ on the street within four minutes.”42 Editors of afternoon papers had so little time to write up the day’s news that they would occasionally prepare two different articles—both “Yale Wins” and “Harvard Wins”—and insert the accurate one into the press as soon as they received reports.43

If extensive publicity and broad news coverage did not hook readers, contests and other short-term lures could do the trick. Many in the business considered the so-called forcing of circulation a cheap tactic, but that did not stop them from doing it. The Baltimore Sun asked readers to vote for the bravest local fireman; the Philadelphia Evening Item asked readers to nominate their favorite trolley conductor.44 Readers would buy one copy of the paper to get the ballot and then would keep buying copies to follow the results. Editors slipped in special inserts, from trading cards to art reprints to sheet music, prompting newsstand rushes on those issues.45 Newspapers could also “force” circulation by running addictive ongoing features. The New York Sun sent a reporter on a frantic trip around the world, and readers bought issue after issue wondering whether she would finish her journey in less than eighty days.46 Reporters also turned news stories into sensational dramas that spilled over from one day’s issue to the next; some readers bought newspapers just to follow these dramas. “Take for example the strange disappearance of Miss Dorthy Arnold,” wrote Marjorie Van Horn, a reader of the New York Evening Journal. “This is a case that I have followed up ever since I first saw its appearance in the journal and I expect to follow it to its end. I am very anxious to know where Miss Arnold is and whether she has become the bride of Mr. George Griscom.”47 The longer the Evening Journal could string this story out, the longer Marjorie Van Horn would keep buying her daily copy.

The most effective method of all for expanding reading audiences was to identify and target populations who did not yet buy the paper. By marketing to these groups and creating content that would appeal to them specifically, publishers could boost sales by thousands or tens of thousands. Publishers pursued these readers so relentlessly that by the early twentieth century they had spread the newspaper habit to nearly all corners of urban society.

In 1880, few newspapers made any real effort to attract women readers. Many women did read the general news and used the paper’s contents in their daily lives. They learned of local marriages, births, and deaths, scanned the help-wanted columns for positions as chambermaids or laundresses, and read the notices of ships’ arrivals in hopes of a husband’s return.48 Yet many genteel families thought that the violence, crime, and politics contained in newspapers made them unsuitable for women readers. William Dean Howells detected traces of this attitude in himself and others as late as 1902: “I saw a pretty and prettily dressed girl in the Elevated train, reading a daily newspaper quite as if she were a man. It gave me a little shock.”49

The rise of the 1890s “new woman”—strong enough to handle disturbing news stories and politically engaged enough to follow current events—may have opened publishers’ eyes to the possibility of female newsreaders. But ultimately, pressure from advertisers and competition from magazines prompted newspaper editors to more energetically pursue female readers. Advertising professionals, writing in journalism trade magazines, pointed out that women spent the household’s money and were therefore more likely to become customers for advertised goods. “An advertisement has not one twentieth the weight with a man that it has with a woman of equal intelligence and the same social status,” explained advertising expert Nathaniel Fowler to his industry colleagues in 1892. “Woman buys, or directs the buying of, or is the fundamental factor in directing the order of purchase, of everything from shoes to shingles.”50 One reader’s suggestion to the New York World seemed to confirm this: “Why not put all the advertisements of the dry-goods houses on one sheet?” she asked. “Then when the ladies of the family wish to read the (to them) most interesting part of the paper they will not have to wait until the males of said family devour the baseball news.”51 Monthly magazines demonstrated that a female focus could be profitable. The Ladies’ Home Journal, for instance, built up a large national audience, and then demanded more from advertisers. By 1903 the magazine was taking in an unprecedented one million dollars per year in advertising revenue.52

When newspaper editors focused on women readers, they made corresponding changes all over the paper. “Every story with a woman in it is ‘played up,’” explained the circulation manager of New York’s Commercial Advertiser in 1905, “and it has become largely a question of ‘the woman in the case’; or, as the detective stories put it, ‘look for the woman.’”53 Some of those woman-centric stories thrilled readers with tales of divorces, jewelry heists, inheritance swindles, and jealous murders. Because they intrigued men as well as women and boosted overall readership, scandals like these moved into the regular front-page rotation. Less sensational newspapers commissioned investigative reports on food processing plants and patent medicine companies, knowing that the subjects of family health and diet lay near to many women’s hearts. Behind the front pages, editors expanded coverage of city art exhibitions, theater productions, and music recitals. They ran highly detailed descriptions of weddings, tea services, and charity balls. They asked their New York and Washington correspondents to comment on society and arts happenings as well as on politics.

Starting in the 1880s and 1890s, editors also created the first women’s sections. Most metropolitan dailies, from the Cincinnati Tribune to the Boston Globe, ran women’s columns by 1895; by around 1905 those columns had become multipage illustrated spreads. The special sections were meant to invite women’s attention and also to signal that the newsroom kept them especially in mind. “The women always find just what they want to read in The Wisconsin,” announced the front page of the 1893 Evening Wisconsin, a Milwaukee paper. “It is the paper for the ladies.”54 In the 1890s, newspapers in several cities ran extraordinary poster campaigns to attract women readers to these sections and to the newspaper habit more generally. In full-color art nouveau prints, papers showed glamorous young women buying, carrying, and reading newspapers (plate 2).

Meanwhile, in their search for more readers, daily newspaper publishers also trained their sights on the working class. Newspaper reading had been a working-class habit at least since the 1830s, but only the biggest cities tended to print newspapers aimed at working-class tastes and budgets.55 By the late nineteenth century, this was changing. E. W. Scripps, for example, was gradually expanding his chain of short, cheap papers meant for working-class readers in cities such as Cleveland, Cincinnati, Saint Louis, and Kansas City. Scripps and his contemporaries all knew that, for a paper to succeed among the working class, it had to be published in the afternoon. Factory workers did not have the time to linger over a newspaper at breakfast, since they started their shifts at seven or eight and either walked to work or commuted on crowded streetcars. Instead, most bought a paper on the way home. Some editors of morning papers began producing separate afternoon editions to capitalize on this market, while many other publishers began issuing independent afternoon sheets. Afternoon papers accounted for 79 percent of the increase in the number of American daily newspapers between 1880 and 1910.56

Around the turn of the century, any bid for working-class readers was also a bid for immigrant readers. The United States admitted over five million immigrants in the decade between 1881 and 1890; it accepted 8.7 million between 1901 and 1910.57 The 1910 census indicated that 15 percent of all Americans had been born in another country.58 The tides of immigrants changed the makeup of newspapers’ potential audiences. Southern and eastern Europeans were replacing waves of Irish and British immigrants, so a greater portion of new arrivals spoke no English. Many read newspapers printed in their native languages, such as New York’s Jewish Daily Forward, Chicago’s Skandinaven, and Milwaukee’s Germania. But even in their own countries, most of these new citizens had not read a daily newspaper. About 12 percent of them could not read at all.59

A few innovative editors tailored their papers to appeal to immigrants of varying reading abilities as well as to the native-born working class. Joseph Pulitzer, editor first of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and then of the New York World, perhaps drew on his own experience as an emigrant from Hungary and as a new reader of English when he revamped both papers. He printed headlines in very large type. Underneath the lead phrase, he added a few subheadings in simple language that allowed readers to grasp the basic outline of the story before they reached the article’s main text. The Scripps chain carried the emphasis on simplicity down to the vocabulary of the news. An editor at a Scripps paper said that he used basic language “not only to save space but also to make the meaning plainer to the man on the street, the man with the pail who quit school at twelve or thirteen. I would use ‘pm’ instead of ‘afternoon’ . . . ; ‘aid’ instead of ‘assistance’; . . . ‘wounds’ instead of ‘lacerations’; ‘chances’ instead of ‘opportunities.’”60 These words made newspaper articles less intimidating to the “man with the pail”; they could be equally helpful for those just learning English.

Editors interested in attracting immigrant readers took the logical next step and put illustrations all over their papers. Pulitzer often devoted a quarter of the front page to a single image and made sure to place it in the top half of the page, so that newsstand customers could see it even when the paper was folded. He scattered smaller images throughout the paper, some of which depicted the action of a news article from beginning to end. This format not only helped readers to grasp the crux of a story, it also served as English practice, letting readers check their understanding of the article against the pictures.61 Pulitzer’s paper succeeded in attracting immigrant readers, but it also grew so spectacular with caricatures, city scenes, celebrity portraits, puzzles, games, and advertisements that even native English speakers might find themselves spending more time on the pictures than on the words.62 Scripps’s illustrations were not so extravagant; he insisted that his pictures always convey information rather than simply dazzle the reader. Still, in the medium-sized cities where he operated papers, he far out-illustrated his competitors.63

A few illustrators experimented further with drawings of sequenced action, and in the process developed a new genre: the comic strip. Starting in 1884, artists at both the New York World and the New York Daily News tried dividing their images into several related sections, depicting a cluster of moments in time.64 Pulitzer separated these images from articles and launched the first comics section in 1889. One of Pulitzer’s early comics, Hogan’s Alley, followed the goofy-looking “Yellow Kid” and his adventures in New York City tenement alleys. When the feature became a runaway hit, William Randolph Hearst, publisher of the rival New York Journal, hired the Yellow Kid’s creator away from the World. Eventually both papers printed a Yellow Kid, drawn by different artists.65 So many readers bought the papers for Hogan’s Alley that people dubbed the Hearst-Pulitzer style “yellow journalism.” A Pulitzer employee claimed that the comics section alone boosted the New York World’s circulation from 250,000 to 500,000.66

1.6 A San Francisco newsstand displays the comics sections as well as the front pages, 1925. Major metropolitan dailies began printing separate (often color) Sunday comics sections like this as early as 1902. San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

The comics proved a runaway success among all kinds of readers; they also provoked anger and disgust. A 1906 Atlantic article described them as “humor prepared and printed for the extremely dull,” filled with “the clamor of hooting mobs, the laughter of imbeciles, and the crash of explosives.”67 Many comic strips took immigrants as their subjects: the Irish Yellow Kid; the German Katzenjammer Kids; Jewish Abie the Agent. Comics tread the line between affectionate ribbing and cruel caricature, but they continually put immigrant humor at the center of the newspaper. And whether readers found them hilarious or offensive, comics seemed a harbinger of a new entertainment age. They drew on the old-fashioned format of vaudeville routines but depicted life in fragmented narrative bits that echoed a fast and fractured urban experience. Their loose language, incorporating ethnic dialect and action words (“wham!”), reflected the hybrid, slangy vocabularies of urban neighborhoods. Comic art played in sophisticated ways with readers’ sense of time and perspective, but still often pandered to the basest levels of humor, with fistfights and bawdy jokes. No wonder so many city readers could not seem to look away.

With comics, newspapers captured one last untapped audience: children. The bright colors and slapstick humor appealed to young readers, and many of the comics’ protagonists—Little Nemo, Buster Brown—were children themselves. Editors noticed that children who loved a certain comic could successfully badger their parents to buy a particular paper.68 Many parents disapproved of their children poring over comic strips, though. Mothers’ groups and education leaders criticized newspapers for running comics at all, and the International Kindergarten Union staged a strike in 1907 to protest violent content in the comics.69 Newspapers aiming for a middle- or upper-class audience began to run tame children’s pages, full of puzzles, poems, and bedtime stories, as more palatable alternatives to the comics. “It is a source of pleasure for us to place this high-class material in their hands,” commented one parent on the Philadelphia Public Ledger’s children’s page, “instead of the usual low-class, vulgar ‘slapstick stuff.’”70 Sanitized children’s material could build circulation just as the comics did. Managers hoped, too, that children might grow up to be loyal readers, so they started clubs for young readers, printed games and activities that could be cut out and constructed from newspaper pages, and included coupons for dolls or paint boxes.71

Mass-circulation newspapers had discovered a lucrative new business model. Their extensive news coverage and special features attracted thousands or even millions of readers. The revenue from advertisements allowed publishers to sell their papers at below the cost of production; in the eighty-page Sunday Journal, the newsprint alone cost William Randolph Hearst more than the three cents he charged for the newspaper.72 The low price further expanded readership. The ad contracts that were to make this whole system possible, however, did not come rushing in. In merchants’ eyes, working-class readers did not shop enough to warrant the expense of advertising to them. Advertising men soon realized this and warned each other in the trade press about “mushroom circulation,” “cheap circulation,” and even “worthless circulation.”73 “Of readers alone a newspaper may get too many for its own good,” explained journalist John Given in 1907, “for a large circulation unaccompanied by advertising receipts in proportion is a costly luxury.”74 With their attention spread so thin over scores of pages, readers did not necessarily notice every ad, either. Merchandisers suspected that their pitch might get lost in a sea of riotous illustrations and text. So while newspaper publishers had bent over backward to increase circulation, ultimately they could not keep enough advertisers on the strength of their circulation alone.

By the early twentieth century, publishers had reconfigured their papers to help sell advertisers’ products. They added sections and issued new afternoon and Sunday editions, all in service to this selling mission. An ad in the 1909 Philadelphia North American paraded the paper’s commercial role within plain sight of all readers:

Selling Power! What is it? It is the ability of a newspaper to sell your goods—

To create in the minds of its readers the desire and the willingness to buy—

To reach the buying public—

To go right into the homes of the people.75

It became a widely known fact inside the industry, and a fairly common comment outside of it, that, as E. W. Scripps put it, newspapers were “fashioned for advertisers.”76

Perhaps the most important concession to advertisers was the creation of separate feature sections. Editors initially commissioned women’s columns hoping to boost circulation and to get women to look at the advertisements sprinkled throughout the paper. By around 1900, though, most editors had turned their women’s sections into shopping forums. They used the sections’ columns to talk about beauty, fashion, or cooking and then surrounded that material with ads specifically targeting female buyers. Sports pages, while not originally intended to sell things, gradually became equivalent sections for men, where articles on boxing ran alongside advertisements for shaving lotion and chewing tobacco. Editors created other sections, such as those for automobiles, bicycles, real estate, travel, and gardening, due to advertiser demand alone.77 For manufacturers who tended to advertise seasonally, newspapers printed special editions; a typical 1915 paper might put out numbers for spring fashion, summer resorts, back to school, and autumn real estate.78 These sections furthered advertisers’ goals not only by creating designated space for advertisements but also by turning people’s attention toward certain subjects and away from others. Newspapers encouraged readers to think about beauty routines, business investments, and vacations; they rarely urged readers to consider spiritual questions or think about improving their working conditions. Simply by editing and organizing daily information into consumer-oriented categories, newspapers pushed consumer habits on news-reading Americans and turned readers into customers.

Many advertisers migrated toward papers with extensive feature sections; many also preferred to buy space in afternoon papers. Afternoon papers attracted working-class readers of both genders—not particularly desirable in advertisers’ eyes—but they also tapped a middle-class female audience. Many men who bought morning papers at newsstands threw them away at work. By contrast, men buying afternoon papers often carried them home, where wives and daughters might also read them. Advertisers reasoned that women running households were more likely to have time to read at night than in the morning. “The morning paper,” explained a writer in Advertising World, “will never be the home paper so long as women are confronted with household duties. When it is fresh, they are too busy to read it and when they are at leisure, it is old.”79 Thus, many merchants preferred to advertise in afternoon papers, which became quite profitable. Many papers actually lost money on their morning sheets, which were heavier on news and lighter on advertising, but made it up in the afternoon, when they recycled much of their morning news and loaded up pages with ads.80 The Milwaukee Sentinel was able to sell its afternoon paper for one cent less than its morning edition; the extra advertisements in the afternoon subsidized the price.

Editors expanded their Sunday papers to turn them into especially effective vehicles for advertisements. Advertisers initially lobbied for space in Sunday papers in the 1870s and 1880s, when Americans began to treat the day differently. No longer content to spend their Sundays in church and in prayer, Americans started to spend their one work-free day visiting amusement parks, taking in exhibitions, ice skating, and riding bicycles. Trolley and steamship companies shuttled day trippers to the countryside or the beach, no longer halting their routes in observation of the Sabbath. Ministers found they needed to give more entertaining sermons in order to compete with cities’ enticing menus of Sunday activities.81 Because more Americans were using Sundays for leisure, they had more time to read a paper on that day. Independent Sunday weeklies saw their sales double; sensing demand, daily papers began printing Sunday supplements too.82

Advertisers bought so much space in Sunday newspapers that editors had to commission more Sunday news and feature content just to keep up. Editors fashioned separate book review supplements, extended the sports pages, and printed fiction in Sunday installments. They created glossy magazine inserts. In an 1898 advertisement for New York’s Sunday World, the Sunday paper appeared as a kind of swirling carnival (plate 3). “Laymen may assume that the Sunday newspaper has more space for advertising because it carries so much more news and feature reading,” explained one circulation expert. “As a matter of fact, the extra news and special features really are carried because the paper has so much more advertising patronage and the displays must be sandwiched with reading matter.”83

Sunday editions swelled to fifty pages, then eighty pages, then over a hundred. One reader of the New York World commented in 1889 that Sunday alone did not afford enough time to take in the Sunday paper. “A grand idea is to have no edition of THE WORLD on Monday morning. Give the people a chance to read your Sunday WORLD through.”84 Overwhelming as these papers may have been, readers could not resist their wealth of attractions. Papers’ Sunday circulations outpaced their weekday numbers by tens of thousands.85

Publishers accommodated advertisers’ needs within their papers but also went one step further by actively recruiting new advertisers. These publishers not only produced an overtly commercial form of media but also took transactions out of neighborhoods and onto the page, drawing individuals and businesses into citywide, print-coordinated economies. Publishers were perhaps most keen on attracting classified ads; unlike other advertisements, classifieds facilitated a dialogue among readers themselves, and a large classified section could guarantee newspapers a steady audience. The Chicago Tribune sent men out in teams to canvass neighborhoods for new classified ad takers.86 Other papers placed decoy ads in their pages to make their classified section appear popular.87 Several newspapers schooled readers in exactly how and why to take out a classified ad, encouraging them to search for a job, piano lessons, or a used automobile in the newspaper. “Mr. Commuter,” said an ad in the 1907 Philadelphia Record, “if Fall charms in the suburbs have been insufficient to hold your maid, try this: Telephone your Help Wanted advertisement to ‘The Philadelphia Record.’”88 Classifieds seemingly put the whole city’s opportunities at the fingertips of any reader, while perhaps reinforcing city dwellers’ tendencies to view many relationships as mere transactions. “5,000 OFFERS to hire, work, buy, sell, rent, exchange,” announced the 1905 New York World. “See Sunday World’s Want Directory To-Day!”89

Publishers hired advertising managers at higher salaries than any other employees and gave ad salesmen expense accounts to wine and dine potential advertisers.90 These managers and salesmen used aggressive strategies with local merchants, such as insisting that any merchant who did not advertise would soon be eclipsed by competitors who did.91 Nathaniel Fowler, advertising specialist, estimated that 75 percent of all periodical advertising came in from these active sales.92 Newspapers waged campaigns for advertising in their own pages, too. The Chicago Defender listed dozens of reasons why people should buy newspaper space, including:

The Philadelphia North American ran short articles that taught readers how to write better ads. “The nearer advertising writing can come to just plain conversation,” it advised, “with that dash of conscious art which a tactful person would inject into casual conversation, the nearer it will get to the mind of the reader.”94 The American Newspaper Publishers’ Association, an industry consortium and lobbying group, issued short daily “talks” on advertising for members to publish.95 These talks often singled out particular organizations—banks, insurance companies, magazines, churches—and explained why they ought to consider advertising.96

Newspapers sometimes won ad contracts with local merchants by providing the services of ad agencies, scaled to a local clientele. Newspaper offices kept distinctive typefaces on hand for advertisers, so each could choose a signature look. Papers designed advertising strategies for merchants and wrote ad copy for them. “If you are not an ‘ad writer’ yourself,” advised R. Roy Shuman in a manual for newspapermen, “employ a bright young man or woman who shows taste and talent in that line, and make advertising easy for those of your patrons who wish to be relieved of the drudgery of preparing the copy.”97

Newspaper publishers pushed advertising to improve their own bottom lines, yet their actions had broader consequences. By pressing local retailers to enter the mass market, publishers stoked a new kind of economy in which small businesses either grew their operations or lost out to larger competitors. “We must reach out and out and out for wider fields. The advertisement is the natural and most effective way of reaching out,” explained Frank Munsey, owner of several major newspapers. “It means that the big houses will get bigger, and that the small ones will disappear.”98 Department stores fully embraced this strategy; by running detailed daily announcements of new items and sales in their local papers, they turned themselves into emporiums with citywide customer bases. William F. King, the president of the New York City Merchants’ Association, even credited newspaper advertising for the very creation of the department store.99 Businesses that did not advertise might suffer simply because they remained out of sight and out of mind of city people, who had learned to look to newspapers for information about the goods and services they needed.

Around 1900, several newspaper editors took up a new and counterintuitive strategy to help boost their advertisers’ sales; they began rejecting certain advertisements. When Collier’s Weekly collected readers’ essays about their newspapers in 1911, the most common complaint was “bad advertising” for patent medicines and miracle cures.100 Some editors began to screen out ads for products that genteel readers might consider vulgar—from dandruff shampoo to alcohol—and rejected those that made obviously false claims. The Scripps-McRae newspaper chain, for example, appointed an ad censor in 1903 who inspected every potential ad and product.101 This tactic boosted newspapers’ circulations among families. “I read the other Kansas City papers—the ‘Journal’ and the ‘Post’—occasionally,” explained a Kansas City resident, “but the ‘Star’ and ‘Times,’ clean in sentiment and appearance, void of all whisky, beer, fraudulent, fake, and patent-medicine advertising, are the papers that come into my home.”102 Newspaper editors screened ads as much in deference to the highest-paying advertisers as to readers. Waldo P. Warren, advertising manager for Marshall Field’s department store, clipped out a piece of medical hokum from the Chicago Daily News in 1902 and sent it to the paper’s editor with an angry note. He dangled the promise of higher profits if Lawson censored ads: “Think of the value of having the News spoken of and thought of as ‘The cleanest paper in Chicago.’ . . . I feel safe in saying that if such a standard of dignity was reached by the News it would call forth a great deal more of our higher class advertising.”103 Papers that screened their ads often did find that they gained more money than they lost, and advertisers were indeed willing to pay more. A merchant who made it into a screened “pure food” section declared: “It is as if you delivered our message from a high place to a waiting and eager multitude.”104

By the first decade of the twentieth century, the search for bigger audiences and the quest to sell more ads had created an entirely different kind of newspaper. The Sunday paper, especially, had become a day’s entertainment in itself. The new abundance and diversity of turn-of-the-century metropolitan newspapers turned them into apt organs for the era’s cities. The colorful pages reflected the polyglot metropolitan populations that newspapers served. As W. T. Stead described, “Just as the people have wide and varied tastes, and the interests of the whole community have to be catered for, everything goes in.”105 The clashing messages within the paper echoed the noise and spectacle of city streets. And as feature writers wove product recommendations through their articles and focused readers’ attention on advertiser-approved topics, they implied that commerce and consumption ought to be central concerns in readers’ lives.

Yet these new metropolitan newspapers offered city people a more solitary reading experience than they had once known. At a price of one or two cents, more Americans could afford to purchase a daily paper of their own. So rather than listening to a brother or a coworker read steadily through the paper’s jumble of information, they now flipped through the pages themselves. And because news came in separate sections, readers could parcel out those sections and exchange pieces of the paper to read silently. Newspapers’ visual appeal, their length, their skimmable headlines, and their separate sections all discouraged people from reading papers from start to finish. As Stead noticed, “No reader is expected to do more than assimilate just such portion of the mammoth sheet as meets his taste.”106 Hundreds of thousands of people might read the same edition of a city newspaper, but when they perused the various sections, they all experienced that paper a little differently.

Newspapers Remake Their Cities

As newspapers attracted ever-larger audiences, they grew into formidable institutions, with large buildings, intricate production and circulation systems, and huge numbers of employees. Newspapers’ operations catalyzed cities’ transitions into centers of industry and of mass culture. They increased the scale and the volume of urban production and sped up the pace of urban life; they changed the makeup of workplaces and the feel of city streets.

Publishers eager to boost their newspapers’ reputations built large and distinctive headquarters that staked a claim to their papers’ broader importance. In the 1880s and 1890s, several publishers grew dissatisfied with their plain urban storefronts, which seemed too humdrum for the brash and confident newspapers they housed. Metropolitan papers were also outgrowing those storefronts as they acquired large presses and hired more workers. Publishers commissioned fifteen- or twenty-story skyscrapers, competing to construct the tallest building in the city. They adorned the towers with signature details—baroque domes, copper turrets, or elaborate clocks—that made them easy to spot from far away.107 The New York Tribune carved its name into the marble at the top of its clock tower. The New York World invited the public up to its top story for a panoramic view of the city and sent them away with brochures detailing the World’s news-gathering prowess.108

Publishers were attempting to create the monuments of their age: testaments to American ambition, wealth, and appetite for information. Senator Chauncey Depew, speaking at the laying of the cornerstone of the New York World building in 1889, picked up on this: “The Pyramids and obelisks of the past, the national monuments of every age, are symbols of force and conquest. These splendid structures built by the modern newspaper, are the results of a combination of brains and business, of mental vigor and culture, of ability in the conduct of affairs, of statesmanship and common sense, which makes possible American literature and perpetuates American liberty. Yonder rises the stories and towers which will tell to all succeeding generations the story and the glory of Greeley and Raymond, of Bennett and Bryant and Dana.”109 In their efforts to turn their new buildings into urban icons, some newspaper owners lobbied to officially rename their districts. Detroit had a Times Square, named for the Detroit Times; Baltimore had Sun Square. In New York, the intersection of Thirty-Fourth and Broadway became Herald Square, and Longacre Square was rechristened Times Square with the arrival of the New York Times in 1904.

Publishers staged events that put their buildings at the center of the action. Newspapers’ staff wrote the latest headlines on chalkboards in the windows or on large marquees over their doors, which encouraged people to stop by the building.110 When especially exciting events were unfolding—such as a major baseball game or an election—crowds gathered to read every update (fig. 1.7). During a highly anticipated 1897 boxing match in Nevada, the New York World placed puppets in a ring in front of its building. The puppeteers received telegraphic reports of each punch and reenacted the match for a crowd of twenty-five thousand people.111 Postings on sports and politics attracted mostly working-class men, who dominated much of the nineteenth-century streetscape. But by the turn of the century, newspaper buildings welcomed other types of visitors. Women entered newspaper lobbies to place classified advertisements, middle-class and wealthy visitors traveled to the tops of newspaper buildings for the views, and various urban professionals rented out offices there. Publishers thus turned their offices into hubs of activity for a cross section of city dwellers.

1.7 Headlines being written up at the New York Tribune (right) and New York Telegraph (left) during the Spanish-American War. Image from Henry W. Baehr, The New York Tribune since the Civil War (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1936), opposite page 226.

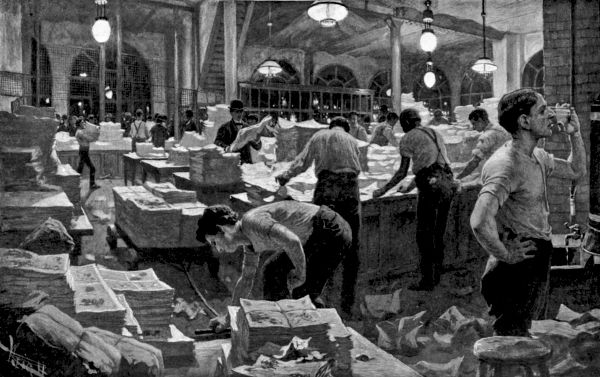

Meanwhile, newspapers’ expanding production and distribution networks demonstrated the capabilities of the industrial metropolis. The largest papers kept more than a thousand regular workers on the payrolls and employed perhaps two thousand as part-time and freelance workers.112 Publishers invited the public into their just-in-time manufacturing operations, showing off the modern and wondrous processes that generated their dailies. Many papers proudly explained their production methods within their own pages; the Milwaukee Sentinel lovingly described every stage in preparing newspaper images and included detailed illustrations of its workers and equipment.113 Magazine articles also sated readers’ curiosity about the inner workings of the news. “The superintendent of delivery has to know exactly when he must have the first papers in order to catch the first mail,” explained Lincoln Steffens in a Scribner’s Magazine article. “The foreman of the press-room must say how little time he needs to run off the first thousand copies; the foreman of the stereotyping-room times his process to a second; and so on back to the news department, which has to be ready for the night editor’s ‘make-up’ in season to ‘go to press’ at the moment determined by the closest reckoning of each chief of staff.”114 (See figs. 1.8–1.10.) These articles alerted readers to the increasing speed and scale of production and turned the reading of the newspaper from a mundane daily ritual into a small way to participate in an impressively modern drama of industrial urban life.115

Meanwhile, the people who reported and sold the news carried a fast-paced modern style out into city streets. Poor and working-class children, hired to sell their papers on street corners, became the consummate urban hustlers. Young workers gauged exactly how many papers they thought they could sell, for news offices would not buy back any leftover copies. Some papers trained newsboys in sidewalk or door-to-door salesmanship techniques; other newsboys figured out on their own how to stake out the busiest intersections, how to find the likeliest buyers for their paper, or which headlines would grab the attention of passersby.116 Thanks in part to the newsboy heroes in Horatio Alger’s popular novels (that appeared starting in the 1860s), newsboys became icons of street smarts, shrewd business sense, and up-by-the-bootstraps success. However, while from one angle newsboys look like nascent businessmen, from another they seem more like the pawns of large corporations. Newspapers’ sales structure, in which newsboys ate the cost of any unsold papers, shifted that financial burden onto the young workers who could least afford it.117 And sales managers employed newsboys in part because they knew customers were more likely to buy a paper from a small child who needed the half-cent profit from each copy than to buy from an adult being paid a real salary.118 The children hawking and delivering newspapers, then, served as poignant symbols of the promise and peril of cities’ competitive economies.

1.8 “The Press Room,” illustration by W. R. Leigh, in J. Lincoln Steffens, “The Business of a Newspaper,” Scribner’s Magazine (October 1897), 450.

1.9 “Receiving Papers from the Elevators,” illustration by W. R. Leigh, in J. Lincoln Steffens, “The Business of a Newspaper,” Scribner’s Magazine (October 1897), 451.

1.10 “The Mail Room,” illustration by W. R. Leigh, in J. Lincoln Steffens, “The Business of a Newspaper,” Scribner’s Magazine (October 1897), 452.

Newspapers’ reporters modeled a bold new way of inhabiting the urban world, and their presence changed the character of city streets. During the day, reporters tracked down newsworthy citizens and often asked them the questions that they least wanted to answer. They scanned birth notices for evidence of illegitimate children, marriage notices for indications of elopements, and obituaries for hints of suicides; they then worked to uncover the details of events that people usually wanted to keep secret.119 They appeared at the scenes of crimes and accidents, prying for details. They did not wait for widows to grieve or for victims to recuperate but insisted on interviewing people while emotions were still raw. Readers usually welcomed the news that these reporters were able to extract. News subjects, however, did not feel so kindly toward reporters (fig. 1.11).a b cd e f

1.11 These images from a 1911 magazine article show a reporter not only visiting the expected news-generating places, such as the legislature (a), a fire (b), and a hospital (c), but also more energetically and creatively pursuing stories. Here the reporter interviews a construction worker (d), gets secrets from a servant in the middle of the night (e), and jumps on the back of a car (f), perhaps to gather information about the man inside it. Will Irwin, “The American Newspaper: A Study of Journalism and Its Relation to the Public,” pt. 7, “The Reporter and the News,” Collier’s Weekly, 22 April 1911, 21–22.

The reporting lifestyle seemed to offer young men all of the romance and danger of the modern metropolis. Authors and academics recommended reporting work as a quick way for any young man to learn the truths of a city and of the wider world. Aspiring writers moved to big cities hoping to prove themselves and perhaps make their names at a metropolitan paper.120 Like other types of workers in turn-of-the-century cities, reporters occupied their own spaces, lived by their own schedules, and spoke their own particular language. They worked late hours and ate midnight suppers in news districts while debating politics and literature. Adding to reporters’ mystique was the notion that they touched the heart of the city, witnessing all facets of urban life. “Its excitements, its outlook upon the world, its opportunities for knowing men, and the sense of power that comes from being a part of such an engine of civilization,” explained reporter Edwin Shuman in 1903, “these things create a spell which the born journalist is loath to break.”121

But journalism could be an unforgiving career path, and the profession demonstrated the hazards of a fast-paced, high-stakes urban economy. Seven out of eight migrants from small papers, warned a former employee of the New York Sun, would fail to find a position at a big-city paper.122 Even those who did get work were probably destined for a “short and brutish” career, as reporter John Reed put it.123 Theodore Dreiser, one of the many men who failed to ascend the ranks of New York City reporters, explained that “men such as myself were mere machines or privates in an ill-paid army to be thrown into any breach.”124 Like industrial-age cities themselves, newspaper offices seemed to prize youth, energy, and resilience. “Reporting involves so much ‘leg work,’ requires so much spurring from the buoying sense of adventure, that, as a rule, only very young men do it successfully,” wrote journalist Will Irwin in 1911. “A reporter’s useful life is about contemporary with that of an athlete.”125 Newspapers’ corps of eager young reporters and their ranks of older, discarded workers together epitomized the labor cycle of modern urban life.

While the newsroom chewed up and spit out male reporters, it also gradually expanded to include female reporters. Many daily papers noted the success of early women columnists such as Jennie June Croly, Grace Greenwood, and Fannie Fern and took on a handful of women writers in the 1880s and 1890s.126 Yet editors often kept women “reserved,” as one reporter described, “for such dainty uses as the reporting of women’s club meetings and the writing of fashion and complexion advices.”127 The majority of women news writers made their livings by writing about traditional female roles, but they pushed boundaries in their own ways. Each time a woman’s name appeared at the top of a column, in the highly public and traditionally male forum of the newspaper, it announced women’s professional arrival.

By the turn of the century, more women were taking up reporting jobs and “male” subjects.128 Women ran city desks, wrote political editorials, and challenged the status quo in muckraking articles. They went undercover as servants, recent immigrants, factory workers, or shop girls in order to expose substandard working or living conditions. Women reporters deliberately covered events, such as hangings, that genteel women were not supposed to witness. They went places, such as downtown streets at night, that genteel women were not supposed to go. Because of this, such authors came to epitomize the seemingly fearless “new women” of the age.129 In New York, Kate Carew (whose real name was Mary Williams) led an especially public career as an interviewer and caricaturist. The World and other papers sent Carew to speak with celebrities, from Jack London to Pablo Picasso to the Wright brothers (fig. 1.12). When Carew and other women reporters ventured onto the streets alone, asked questions, and presented themselves as proficient newsgatherers, they helped to create a world in which women increasingly operated as professionals and public figures.

1.12 Kate Carew’s caricatures always depicted both her subject and herself. Unlike most cartoons of women at the time, she appeared neither as a young fashion plate nor as a dowdy housewife but as an inquisitive, slightly shy, bespectacled interviewer. Carew worked for the New York World in the 1890s and 1900s, for the New York Journal in the early 1900s, and for the New York Tribune in the 1910s. New York Tribune, 19 May 1912, sec. 2, 1.

Newswomen also accustomed people to a female presence in an overwhelmingly male work space, a trend that would continue as more and more women took jobs in city offices and shops. Women news workers sometimes provoked resentment among male editors and reporters, who suddenly felt more self-conscious about their newsroom culture of curse words, dirty jokes, and alcohol.130 Reporter Flora McDonald wrote that she felt forever “a fish out of water” in the male-dominated newsroom.131 Many of the first women journalists avoided newsrooms by working from home, bringing pieces to their editors once a week or sending them in by mail.132 Yet other women simply adjusted. Isabel Worrell Ball, a congressional reporter for the Topeka Capital, put it this way: “If a man wants to smoke in her presence when she is at work, or keep his hat on, or take his coat off, or put his feet on the desk, or do any of the things which she would order him out of her parlour for doing, she must remember that it all goes with the place she is in.”133 The Journalist, a trade publication, was more pointed: “The girl who has it in her to survive for newspaper work will cry the first time a man swears at her, grit her teeth the second time, and swear back the third time.”134 Female journalists forced men to recognize that women could tolerate, and even thrive in, male-dominated offices.

Editors in need of feature news and illustrations hired large corps of freelance writers; these writers diversified the types of voices heard within the paper but were rarely treated as equals to their full-time counterparts. The specialized nature of feature writing lent itself to a freelance structure. No paper needed a staff reporter who concentrated solely on boxing, cooking, or philanthropy, but a freelancer could build a career by picking one of those topics and writing about it for a number of newspapers. Freelancers worked from locations all over the country, but they concentrated in New York, selling work to magazines and Sunday papers nationwide.135 Freelance jobs offered more flexibility than salaried jobs; women could write even while raising children at home.136 Freelancing, however, offered none of the job security, oversight, or training that salaried journalism provided.

The freelancers who pitched articles and the editors who bought them treated news as a commercial product. Unlike a salaried worker, a freelancer was likely to draw a direct line from an idea to the profit it might produce when written up. “It does not matter where you live,” stated a 1910 brochure for a correspondence course in journalism. “Wherever there are people there is news, and my instructions teach you how to turn it into money.”137 Writers learned to describe their work to editors as appealing merchandise. “All the news of every kind from Oklahoma and Indian Territories, by mail or wire, always fresh, brief and reliable,” advertised one freelancer in a trade magazine. “Indian news and sketches a specialty. You state what you want, I’ll do the rest.”138 The structure of freelancing pushed writers to treat their own names as brands to be continually promoted and to treat their pieces as goods to be purchased and consumed.

As newspapers adopted a twenty-four-hour schedule, they subtly altered the rhythms of urbanites’ lives. Newspapers took it as their responsibility to report all important events and so kept their office doors open, their telegraph lines ready, and their reporters working through the night. The New York Herald even kept its classified offices open until 10 P.M.139 Newspapers required intense labor at night in order to get their papers out by morning, so their employees worked staggered shifts. Most writers reported for work in the early afternoon and finished after midnight. As those writers headed to supper clubs in the neighborhood (which stayed open late just to serve the news industry), the compositors set the news into print. Printers, working from perhaps midnight until six in the morning, turned out the finished product, and the papers’ distribution force then shuttled papers around the city at dawn.140 As newspapers took to printing several editions per day—anywhere between two and ten—they had to engineer even more round-the-clock operations, using a second set of reporters, compositors, printers, and distributors.141 Cities that housed major newspapers became cities that truly never slept.

The all-hours nature of the news industry likely affected city dwellers’ sense of time. No event occurred too late or too early to be picked up by the news; thus was no city hour entirely private. Nor was any hour truly quiet and still, for there was always a fresh edition of the paper to be read and digested. Some readers found these constant editions comforting and came to rely on them. “As long as I have been a reader of the evening journal it has been a great comfort to me,” explained reader Marjorie Van Horn. “Nights when coming home from work I would feel very down hearted and when I would get this paper and read it I could go to rest with great ease.”142 Others might find the arrival of new editions relentless—far too much to keep up with. Whether readers welcomed or resented them, the stacks of fresh papers on newsstands reminded everyone that all through the day and night, dramas had been unfolding, presses had been churning, and the city had been making news.

The Objectivity Question

Until the late nineteenth century, most papers had operated under the auspices of a single owner or a primary owner plus several investors. The owner usually served as the paper’s editor; he also purchased all of the equipment, paid the employees, pocketed any profits, and suffered all of the losses. A handful of these owners operated independently. More of them enlisted support from a political party, in the form of equipment, free rent, volunteer labor, or cash. In return, editors stuck to party lines in their editorials and talked up the causes that local party bosses championed.143 However, by the 1880s and 1890s, to stay competitive in an expanding industry, many newspaper publishers needed more funds than local party leaders or a few wealthy investors could provide. Thus, publishers would invite several hundred investors to own a small part of the paper and share in its gains or losses, incorporating the papers as joint-stock enterprises.144

Editors, when entrusted with shareholders’ money, often acted conservatively. “Some editors are fortunate enough to be able to make their papers pay on lines conforming with their own ideas in most matters, but there is none who has not had to suppress many of his private views,” explained Edwin Shuman in 1903. “He is only one of many whose money is invested in the paper, hence he has no right to wreck it for the sake of any idea, however dear to him.”145 If profits began to slip, the newspaper’s board could ask an editor to step down. Jointly held papers could remain political organs, but more often they expressed moderate views in an attempt to attract readers from all parties. The corporate model clearly discouraged experimentation. The greatest newspaper innovations of the late nineteenth century came from papers still operating under sole proprietors. Neither Joseph Pulitzer nor William Randolph Hearst, for example, issued stock for their newspapers.146

Corporate structures pushed newspaper editors to approach their work like businessmen, to treat an editorship more like a salaried position than like a crusade or a calling. “What I want is the reader who likes to talk,” said a newspaper manager in an 1897 interview, “and then I want to set him talking; to make him turn to the next man and ask him if he has read something in my paper. That advertises the paper and sells it, which is the thing I am after. I have no mission, you know.”147 Many editors chose their line of work because they loved the news and hoped to shape public opinion; they would never go so far as to say they had “no mission.” But by the early twentieth century, most editors had to balance their own views with the business needs of their large, corporate papers. Managing editors, and lower-level editors as well, might feel more accountable to their shareholders, their supervisors, and their customers than to their own convictions.

Corporate newspapers’ emphasis on moderation and steady profits gave rise to a new reporting ideal: objectivity. Highly structured corporate papers found it safest to produce neutral news. Eventually, reporters embraced this objective role, putting it at the center of their professional identity. “Tell the truth and dare to stand back of it,” urged a 1906 manual for reporters. “Be impartial, unprejudiced.”148 Journalists issued pamphlets with titles like “The Ethics of Journalism” to standardize codes of conduct, and some reporters were so wedded to the objectivity ideal that they refused to register as members of any party, since it would give readers an indication of their personal political sympathies.149

While corporate structure encouraged nonpartisan news coverage, advertising revenue helped make objectivity financially viable: money from ads could substitute for the income once received from political parties. Melville Stone, editor of the Chicago Daily News, articulated this platform for his independent newspaper. “In its every phase as a news-purveying organ, or as a director of public opinion, it must be wholly divorced from any private or unworthy purpose,” he argued. “It must have only two sources of revenue—from the sale of papers and the sale of advertising.”150