I must admit I have been a bit irritated by recently published books and even magazine articles advocating “home” distilling. I know I’m way too literal most of the time, but to me, “home distilling” is misleading. The fact is, United States federal law prohibits the use of a still for liquor production inside your home, even if you are a licensed distiller. These books and articles were encouraging readers to make small stills using a teakettle or even a pressure cooker, to be used on the kitchen stove.

As you’ve already learned, there are a few specific safety issues that are critically important to be aware of with distilling. You might be thinking that if you do this on a small scale in your kitchen, who will know? Yes, you might get away with it. You probably believe that you’re taking all precautions and nothing bad could possibly happen. Whatever else I think about most of the laws around distilling, I do totally agree with the idea of not running a still inside a home. It is simply not worth the risk, and you may also run into problems with insurance (see sidebar).

When I first applied for my distillery license, I was surprised to get a phone call a couple of weeks later from our local fire inspector. Evidently the Liquor Control Board had forwarded notice of my application to him. He was very nice and explained that he wanted to come inspect my “facility.” I explained to him that I didn’t have a “facility;” I didn’t even have a still yet. My plan (such as it was) was to build a small still and use it on a propane burner on my patio. This clearly stumped the poor man, who said he would need to check something and call me back.

When he phoned me the next day, he said apologetically that it would not work for me to set up my distillery the way I had described. It definitely needed to be in a separate building. (I was later told by the regional Liquor Board inspector that a lot of small distilleries were being set up in garages.) This news left me feeling even more discouraged. I had visions of county health inspectors giving me a long list of requirements like top-to-bottom stainless steel, tile floors and a lot more.

Much to my relief, I found out that, at least in our state, the requirements for the building are as follows: four walls, a roof and a door that locks. That’s it! I started thinking about it and looking around our place to see if something fitting that description was available.

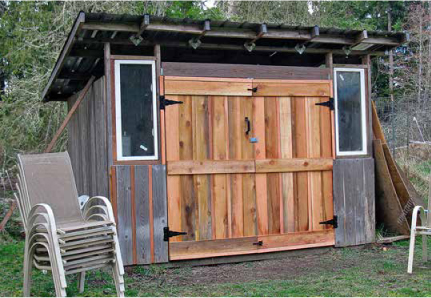

It didn’t take me long to spy a shed I had built several years earlier for our pigs. I had a smaller house I had built for pigs, but it really only worked well when we had two pigs, and only when they were smaller. It was definitely too small for three pigs, at least when they got to over 100 pounds or so. The new shed, which is built on skids to be easily movable, is about 8 feet by 10 feet. Luckily it had a high enough roof that I can easily enter and move around in it; actually the sloping roof is about 8 feet high at the doorway. At the time the front was completely open, but I built double doors onto it and added a sturdy hasp and a heavy-duty padlock.

My little stillhouse, converted from a shed I originally built for, well, pigs.

So what do you need in your little distillery besides a still? Well, you need some way to heat the still. Depending on your situation, you might use electric heat, a propane burner or even a wood fire. You’ll need access to running water for the condenser, and the appropriate hoses or tubing to connect the water to the still. You’ll need containers to collect the distillate from the still and more containers with lids to age and store your finished spirits. Let’s see: oak chips, cubes or barrels if you’re going to be aging spirits with oak. Filtering equipment if you’re making vodka. Various herbs and spices if you’re making gin or bitters or liqueurs.

If you’re also going to be doing your mashing in your stillhouse, you’ll need good storage for your grains to keep moisture and rodents out. Maybe a grain mill. If you’ve been making your own beer, you probably already have all the required fermenting equipment. (See below for a fairly complete list if you are starting from scratch.)

Yet another thing that’s not discussed much: Make sure you have something to do in your stillhouse while you’re distilling. There’s not actually all that much hands-on time during a small-scale distilling run, and you will be keeping an eye on things for probably two to three hours. We don’t have cell phone reception or wireless Internet at our place, which might be just as well; I daresay it would prove just as big a distraction in the stillhouse as it is elsewhere. I usually bring at least one book, my MP3 player and headphones, and a notebook and pen.

I also have a dartboard in the stillhouse; turns out that if I stand just outside the threshold on the long door side, I’m almost exactly at the regulation distance from the board. If it sounds silly, I challenge you to try it. It’s a lot of fun. Just make sure it’s placed so you’re not tripping over your still in the process of retrieving the darts from the ceiling.

Now you know what I do when I’m waiting for the still to come to a boil.

Besides the obvious still, there are quite a few things you should have on hand if your aim is to make really top-quality spirits. Don’t let this list frighten you; you don’t necessarily need to buy everything all at once. Eventually, though, if you are milling and mashing your own grains, you will find that most of this equipment will come in very handy.

Most of it can be found at homebrew and wine-making supply shops. If you’re just starting out, do try to find a local shop; relatively large things like buckets can get a bit expensive to ship.

• Grain mill (optional but nice)

• Mashing pot with lid (size depends on how much grain you will be mashing in a given batch; I use my stainless steel 10-gallon (38-liter) stockpot, as it is of ample size to handle 15 pounds (6.8 kg) or more of grain at one time)

• Large plastic, stainless steel or wooden spoon for stirring

• Accurate thermometer

• Kitchen scale capable of weighing at least 10 pounds (4.5 kg) at a time

• Large food-grade buckets with tight lids for storing grain

• pH meter or pH test strips (I recommend investing in a pH meter if you are going to be doing a lot of this kind of thing; it’s absolutely worth it.)

• Tincture of iodine (for testing mash for starch conversion)

• Immersion chiller (optional)

I keep all my distilling grains in food-grade buckets with tight-fitting lids.

• At least 2 fermenting buckets with lids; a good size is 25 liters, about 6.6 US gallons

• Airlocks

• Good airtight storage for yeast and enzymes

• Hydrometer and test cylinder

• Siphon for transferring wort to the still

• Heat source for heating the still

• Water supply for the condenser, and some means of reusing or disposing of the water (see the discussion on water in chapter 10)

• Graduated cylinders for collecting distillate. You can use other kinds of containers, but I find it very handy to use graduated cylinders. I have a 1-cup (250-milliliter [ml]) cylinder that collects the distillate as it comes from the still, and a 2-cup (500-ml) one that I dump the smaller one into when it fills up. I like to keep track as I go along, especially when doing a spirit run.

• Jars or bottles, with lids, for storing low wines, heads and tails, and finished spirits

The alcohol refractometer, a very handy tool for distilling.

• Approved fire extinguisher (check with your local fire department for the specific type needed)

• Alcohol refractometer. Not absolutely necessary, but it makes it so easy to check the ABV of distillate, particularly handy when you are doing spirit runs. Make sure you ask for an alcohol refractometer, as there are different types of this instrument, such as the Brix type. Do try to find a good-quality one.

• Hoses and other equipment for flushing and cleaning your still

• A notebook for record keeping. I am pretty sure you will regret it if you don’t. I always think I’m going to remember from one batch to the next what exactly I did, but almost every time I have been wrong. I know I harp on this, but it’s a good habit to get into.