Despite the fact that contemporary critics panned its “brutalizing violence and grotesque comedy” (Mahoney, 1967) and remarked on its “sadistic, brutal, and inhuman [final] scene” (Ebert, 1967), The Dirty Dozen (Johnson and Heller, 1967) has become “one of the most enduring, if preposterous, World War II movies to come out of Hollywood” (Weber, 2016). In fact, it was nominated for four Academy Awards and it is listed at number 65 on a list of the “100 most thrilling American films” compiled by the American Film Institute (American Film Institute, 2019).

The Dirty Dozen is a reflection of its time. Released during the Vietnam War, its anti-establishment, anti-authority, anti-everything message includes misogynistic and macho dialogue shocking to today’s audiences (Editors, 2019). It is a movie that shows the darker side of war, where soldiers are not all heroes but also include socially dysfunctional individuals, violent misfits who bristle at authority and march to the beating of their own drum (Berardinelli, 1998). At the same time, its plotline about camaraderie among outcasts standing up against abusive authority has proven enduring. The movie does not depict the triumph of the individual hero against foes at home and abroad but instead shows the collective struggle of “tough-guys-being-tough-together” (Collis, 2000). This struggle is effectively a game (Editors, 2019) where the rules can and are indeed subverted. Nevertheless, the game is not won by the Dozen, who perish instead of finding redemption through their inhuman actions.

The movie contains two scenes well suited to illustrate the classic ultimatum game described in McCain (2004) and Dixit, Skeath, and Reiley (2015), one from the point of view of analytical theory and one informed by behavioral theory.1 In the first scene, a proposer makes an unappealing offer to a responder who has such a low opportunity cost that he chooses to accept it. Self-interest dominates. In the second scene, a proposer makes an unappealing offer to a responder who rejects it in order to lower the proposer’s payoff. This comes at a cost to the responder, who could be argued to be envious. Setting aside the underlying structure of his utility function, strict self-interest does not dominate. Thus, The Dirty Dozen illustrates Nash equilibria (see McCain, 2004; Dixit et al., 2015) and self-serving behavior as well as the impact of social preferences on individual behavior.2

The movie

Set during World War II, the story in The Dirty Dozen mostly takes place in England during the months leading to Operation Overlord, the Allied landings in Normandy.3 The Allied Expeditionary Force command, embodied by General Worden, plans to facilitate the invasion of German-occupied Western Europe by taking out the German Army’s high command with one bold stroke. The plan is to parachute a commando unit behind enemy lines and attack a mansion where the German officers cavort with their mistresses amid canapes and champagne. The plan is bold and risky. The commando unit will have to operate unassisted and the odds of failure are so high that the U.S. command decides to spare its regular commando forces and form a new unit.

Given that the mission is almost suicidal, General Worden orders Major Reisman to recruit a group of military convicts to execute it. The convicts are serving their sentences in a stockade for a variety of crimes including murder, manslaughter, rape, assault on an officer, as well as other unstated offenses. Reisman meets each and every candidate to join the Dozen and offers him the same deal: join the group, train for the mission, execute it successfully, return alive, and your sentence will be commuted. Only individuals with a very low opportunity cost (i.e., those already facing the gallows or with very long prison sentences) are likely to take on the offer. Many protest and are reluctant to place themselves under the authority of Reisman, but all accept the offer: a chance at redemption or certain death. With the expository part of the narrative out of the way in the first 30 minutes of the movie, the body of the plot develops.

The Dozen are trained in hand-to-hand combat and parachuting, and are, most importantly, imbued with the esprit de corps needed for a small unit to succeed. Reisman trains his soldiers in unorthodox ways and along the way their individual personalities become more clearly defined. One among the Dozen, Victor Franko, proves to be the most hostile to authority and downright antisocial. His selfishness and nihilism puts him in conflict with his peers and he is beaten up by two of his comrades when attempting to desert the unit. He is no altruist, but as the story moves on he bonds with the group and transfers his hate for authority from Reisman to Colonel Everett Dasher Breed. This character provides another source of conflict in the story. Breed holds some unspoken grudge against Reisman and wants him to fail on his mission. In order to sabotage Reisman, Breed applies all the pressure he can muster from his position of command to force the Dozen to reveal who they are and the nature of their mission. Given that the mission is classified, exposure would lead to its cancelation and the return of the Dozen to the stockade. In a highly dramatic scene, Breed uses his own troops to pin the Dozen down and seems close to coercing a hapless platoon member named Vernon Pinkley into talking. Breed’s machinations are derailed first by Franko, who taunts him and draws him away from Vernon, and then by Reisman, who saves the day by backing up his small unit against the bully.

At this stage of the story the Dozen have become a cohesive group and they prove their mettle first by defeating the opposing team during a “war game” and then by completing their mission behind enemy lines. In the climax of the movie, the Dozen unleash all of their murderous impulses against the German officers and their mistresses. Not much is left to the imagination as the enemy and a substantial number of collateral victims are locked up in a basement and blown up with gasoline and grenades. All but one of the Dozen perish during the operation and in the closing scene viewers see only Reisman, his second-in-command Sergeant Bowren, and Joseph Wladislaw recovering in a hospital.

The game

The movie presents two distinct opportunities to illustrate the ultimatum game. In the first instance, the game illustrates a strictly rational, analytical strategy. Early in the movie, while assembling his small commando unit to-be, Major Reisman interviews each of the convict candidates to join the Dozen. The first one of them is Private Franko, who receives the following ultimatum: join the daredevil outfit or serve your death sentence. As suicidal as the mission assigned to the outfit may be, self-preservation dominates: a chance to live is superior to certain death. Thus, the offer is accepted. Figure 4.1 depicts the decision tree and numerical payoffs for both officer and private. If the offer is accepted, the proposing officer achieves his recruiting goal and the responding private gets to live another day. Note that the payoffs differ because this outcome has disparate impacts for each player: professional redemption for the officer and mere reinstatement as regular private for the soldier. If the offer is rejected, the proposing officer fails to achieve his recruiting goal but can move on to attempt and recruit another convict. The responding private, however, is eventually executed. The payoffs are very disparate and for clarity of exposition this modeling approach bounds the payoff of swinging from the gallows to zero.

Figure 4.1 The ultimatum game: join or serve your sentence

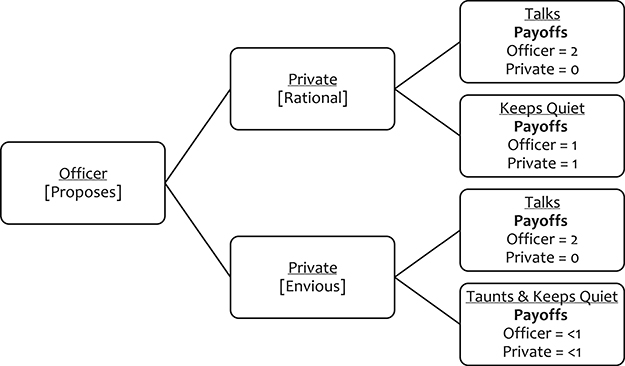

In the second instance illustrating the ultimatum game, The Dirty Dozen touches on behavioral theory strategies described by Camerer (2003) and reviewed by Angner (2016). Halfway through the movie, after undergoing training and developing a modicum of esprit de corps, the Dozen receive another ultimatum from a different figure of authority. Colonel Breed orders the privates to talk about their mission or suffer the prescribed consequences to an act of insubordination. Here, again, self-preservation dominates: talking will expose the secret mission, canceling it, and sending the convicts back to the gallows. Everybody keeps quiet. The top branch of Figure 4.2 depicts the decision tree and numerical payoffs for both officer and private. If the offer is accepted, the proposing officer achieves his goal of revenge and the responding private is eventually executed along with his peers. As before, the payoffs differ because this outcome has disparate impacts for each player: self-gratification for the officer and death for the private. If the offer is rejected, the proposing officer fails to achieve his revenge but can move on to seek it again in the future, while the responding private continues with his mission.

In this case the game goes on for an additional, unexpected, round: Private Franko taunts Colonel Breed, displaying the same hostility to authority that he exhibited earlier toward Major Reisman. By disrespecting Breed’s status as a superior officer, Franko draws his attention and infuriates him. Colonel Breed orders the private to talk and ups the ante: under the pretense of maintaining hygiene, Franko’s beard will be shaved without the use of water and soap. This is a blatant threat of torture. The bottom branch of Figure 4.2 depicts the decision tree and numerical payoffs for both officer and private. As earlier, if the offer is accepted, the proposing officer achieves his goal of revenge and the responding private is eventually executed along with his peers. If the offer is rejected, the proposing officer is aggravated by the insubordination and fails to achieve his revenge, but can move on to seek it again in the future, while the responding private is physically abused but continues with his mission. Both proposer and responder are receiving lower payoffs relative to the scenario described in the previous paragraph.

Figure 4.2 The ultimatum game: talk or keep quiet

How can this deviation from a strictly rational strategy be understood? A survey of the experimental economics literature by Camerer (2003) shows that most players of the ultimatum game avoid highly unequal proposals (i.e., a lot for me and very little for you). Social preferences might play a role in crafting balanced offers (i.e., not too much for me and not too much for you), attributing potential altruistic impulses to the proposer. Conversely, avoiding envious impulses on the part of the responder might also lead to the crafting of balanced offers. In the absence of balanced offers, retribution might kick in. Behavioral game theory has documented the phenomenon of negative reciprocity, or rejecting a positive offer in the ultimatum game. According to Gächter (2004, 492), a person has negatively reciprocal preferences if she is “willing to pay some price to punish an opponent for behavior that is deemed unfair or inappropriate.” In the case at hand, the responder chooses a game strategy where the proposer’s payoff is lower, even if that requires lowering his own payoff as well.

Conclusion

A motion picture described by contemporaneous critics as an “astonishingly wanton war film” (Crowther, 1967) is now recognized as seminal to its own genre (Fuster, 2017). The Dirty Dozen has achieved iconic status not because of its groundbreaking realism or because it brought to light a historical episode of overlooked importance. In fact, critics have remarked on its factual and production flaws (Mahoney, 1967; Berardinelli, 1998), and the author of the book on which the screenplay was based has dispelled the notion that the story is anything but fiction (Weber, 2016).

The movie’s impact on popular culture has projected it across time and movie genres. Its basic premise about a small group of outcasts who are forced, by friendship, duty, or threat of punishment to fight against appalling odds has been replicated in nihilistic movies such as The Wild Bunch (Green and Peckinpah, 1969), The Longest Yard (Wynn and Ruddy, 1974), and Suicide Squad (Ayer, 2016), as well as in family-friendly, super-hero, block-buster movies such as The Avengers (Whedon, 2012) and Guardians of the Galaxy (Gunn and Perlman, 2014). In an example of movies referenced in other movies, The Dirty Dozen’s emphasis on male camaraderie was highlighted in the romantic comedy Sleepless in Seattle (Ephron, Ward, and Arch, 1993) when the male lead and his long-time friend mockingly reminisce about The Dirty Dozen’s final scene as a boorish counterpoint to the sentimental recanting of An Affair to Remember (Daves and McCarey, 1957) by one of their spouses. The fact that 26 years after its release a war movie as blatantly violent as The Dirty Dozen made its way into a romantic comedy such as Sleepless in Seattle clearly speaks about arresting themes behind its brutal facade.

The Dirty Dozen has additional appeal in the academic realm given that it includes at least two scenes that demonstrate the power of the classic ultimatum game that illustrates some of the central tenets of game theory. In one scene the movie depicts a strictly rational and analytical version of the game, wherein each of the 12 convict recruits accepts the U.S. Army’s invitation to form a commando unit. In the other, the movie portrays an ultimatum game involving behavioral theory strategies, wherein each of the 12 convict recruits chooses to maintain the secrecy of their mission behind German lines.

References

American Film Institute. 2019. “AFI’s 100 Years…100 Thrills: The 100 Most Thrilling American Films.” AFI.com.

Angner, E. 2016. A Course in Behavioral Economics. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

Asarta, C.J. and F.G.Mixon, Jr. 2020. “Did a Game-Theoretic Device Save the Lone Survivor?” In War Movies and Economics: Lessons from Hollywood’s Adaptations of Military Conflicts, edited by L.J. Ahlstrom and F.G.Mixon, Jr. London, UK: Routledge.

Ayer, D. 2016. Suicide Squad. Los Angeles, CA: Warner Brothers/DC Comics.

Berardinelli, J. (1998) “The Dirty Dozen.” Reel Views, June 30.

Camerer, C.F. 2003. Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Carter, J.R. and M.D. Irons. 1991. “Are Economists Different, and If So, Why?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5, 171–177.

Collis, C. 2000. “Empire Essay: The Dirty Dozen.” Empire Online (EmpireOnline.com).

Crowther, B. 1967. “Brutal Tale of 12 Angry Men.” The New York Times, June 16, 36.

Daves, D. and L. McCarey. 1957. An Affair to Remember. Los Angeles, CA: Jerry Wald Productions.

Davis, D.D. and C.A. Holt. 1993. Experimental Economics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dixit, A., S. Skeath, and D. Reiley. 2015. Games of Strategy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Ebert, R. 1967. “The Dirty Dozen.” RogerEbert.com.

Editors. 2019. “The Dirty Dozen.” Time Out (TimeOut.com).

Ephron, N., D.S. Ward and J. Arch. 1993. Sleepless in Seattle. Los Angeles, CA: TriStar Pictures.

Fuster, J. 2017. “A Dozen Movies Influenced by The Dirty Dozen as Film Turns 50.” The Wrap, June 14.

Gächter, S. 2004. “Behavioral Game Theory.” In Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making, edited by D.J. Koehler and N. Harvey. London, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 485–503.

Green, W. and S. Peckinpah. 1969. The Wild Bunch. Los Angeles, CA: Warner Brothers/Seven Arts.

Gunn, J. and N. Perlman. 2014. Guardians of the Galaxy. Los Angeles, CA: Marvel Studios.

Johnson, N. and L. Heller. 1967. The Dirty Dozen. Los Angeles, CA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Kroncke, C.O., Jr. and F.G.Mixon, Jr. 1993. “Are Economists Different? An Empirical Note.” The Social Science Journal 30, 341–345.

Mahoney, J. 1967. “The Dirty Dozen.” The Hollywood Reporter, June 16.

McCain, R.A. 2004. Game Theory. Mason, OH: Thomson-Southwestern.

Nash, J. 1950. Non-Cooperative Games. Doctoral Thesis, Princeton University.

Thaler, R.H. 1998. “Anomalies: The Ultimatum Game.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 2, 195–206.

Weber, B. 2016. “E.M. Nathanson, Author of The Dirty Dozen, Dies at 88.” The New York Times, April 8, 14B.

Whedon, J. 2012. The Avengers. Los Angeles, CA: Marvel Studios.

Wynn, T.K. and A. Ruddy. 1974. The Longest Yard. Los Angeles, CA: Paramount/Albert S. Ruddy Productions/Long Road Productions.