6

The Battle of Dunkirk

Analyzing economics principles in two motion picture portrayals of an epic retreat

Between May 26, 1940, and June 4, 1940, British, French, and Belgian troops hemmed in along the beaches in the port of Dunkirk were forced to retreat as the advancing German Army tightened its noose on northern France. By the end of this period, 336,000 troops had been evacuated successfully (to England), with about 30,000 left behind in what was known as Operation Dynamo (Summerfield, 2010). The portrayal of this battle for survival was the subject of two films produced with the same name Dunkirk, in 1958 and 2017.

The first of these, Dunkirk (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958), was the second-highest grossing British film of 1958 in England, and it is now acclaimed as a Vintage British Classic movie, with “an all-star cast of the finest British actors of its time” (Adler, 2017).1 The movie is based on two novels, The Big Pick-Up and Dunkirk (Crowther, 1958). While the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, that drove the entrance of the United States into World War II resulted in American audiences becoming interested in war-based movies (Sutter, 2012), Dunkirk (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958) was not very successful in the United States. It became profitable mostly through sales outside the United States. There was a gap of nearly six decades between the production/distribution of the first Dunkirk (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958) and that of the second (Nolan, 2017).2 Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017) portrays the Dunkirk evacuation from three perspectives – land, sea, and air.3 It offers little dialogue, as Nolan (2017) sought instead to create suspense from cinematography and music.

This chapter begins with a brief historical introduction highlighting the significance and context of the Dunkirk evacuation. We then proceed by applying economic concepts to scenes from the movies. These include the core concepts of economic resources, scarcity, opportunity cost, rational decision making, cost-benefit analysis, the efficiency-equity tradeoff, comparative advantage, and supply and demand. The economics concepts within the two Dunkirk movies also relate to those used by industrial organization scholars, such as strategic thinking using game theory. With examples and vignettes from Dunkirk catalogued in a single study, our chapter extends the growing academic literature on economics in the movies.4

Blitzkrieg, the war in Europe, and the significance of Dunkirk

The invasion of Poland in September of 1939 and its rapid conquest by Germany marked the beginning of a blitzkrieg (or lightning war) that ended with the conquest of France and the Allied forces’ retreat from Europe. Germany’s strategy to defeat its opponents in a series of short campaigns was successful as it was victorious for more than two years. Denmark (April 1940), Norway (April 1940), Belgium (May 1940), The Netherlands (May 1940), Luxembourg (May 1940), and France (May 1940) were conquered in rapid succession before the end of 1940. In France the final battle to halt the German advance was fought near Dunkirk. During the Dunkirk evacuation, England assumed that a German invasion was inevitable (Bond and Tuzo, 1982). However, Germany never invaded England, which was protected from German ground attack by the English Channel and the British Royal Navy. Thus, for much of 1940 and 1941, Great Britain was involved in a rear-guard action in Europe, in an attempt to ensure that England would not be invaded.

In June 1941, after conquering both Yugoslavia and Greece, Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Despite two major offensives, however, Germany was unable to defeat the USSR, which together with Great Britain and the United States seized the initiative from Germany by the end of 1942. Germany became embroiled in a long war, leading ultimately to its defeat in May of 1945. Following this, Japan (which had entered the war on the Axis side in December of 1941) was defeated in August 1945.

The Battle of Dunkirk was fought between the Allies (primarily France and Great Britain) and Germany. It culminated in a retreat by the Allies to the Channel coast in the face of the remorseless German blitzkrieg that ended on the beaches in the south and western parts of France. Allied troops were being hemmed in along the beaches of Dunkirk, with the advancing German Army tightening the noose daily. As Macdonald (1986, 10) points out, “[f]ight and fall back, fight and fall back became the daily norm of the tired men of the British Expeditionary Force and of those French and Belgian units still holding together.”

In one of the most controversial decisions of WWII, the German Army interrupted its advance on Dunkirk following a “Halt Order” confirmed by Adolf Hitler on May 25, 1940, and rescinded, again by Hitler, late in the evening of May 26, 1940 (Macdonald, 1986; Messenger, 1989). The interregnum gave the Allies sufficient time to build a makeshift defensive line and to organize the evacuation of the surrounded troops.5 The evacuation began in the early hours of May 27, 1940, and the first vessel to arrive embarked 1,420 troops. Over the remainder of May 27 and all of May 28, 1940, 25,000 men would be evacuated from Dunkirk (Messenger, 1989). On May 29, 1940, 47,300 soldiers were evacuated, while almost 54,000 additional Allied soldiers were ferried back to England on May 30, 1940. By this time the rescue flotilla consisted of a number of “little ships,” ranging from cross-Channel ferries to small pleasure craft (Messenger, 1989).6

On the last day of May in 1940, 68,000 Allied soldiers were rescued from the beaches at Dunkirk, marking the most successful single day of evacuation during Operation Dynamo. This success was followed on June 1 and June 2, 1940, when, respectively, 65,000 and 24,000 men were rescued (Messenger, 1989). On June 3, 1940, which was the last day of the evacuation, 26,700 men were rescued (Messenger, 1989). While more than 336,000 Allied troops were rescued (Summerfield, 2010), about two-thirds (one-third) of which were British (French), British and French military forces sustained heavy casualties and were forced to abandon nearly all of their equipment (Messenger, 1989).7

Dunkirk and economics

Economics is defined as the study of how limited resources are allocated among competing uses (Mankiw, 2018). An economy functions by producing output, either in the form of goods (tangible) or services (intangible), in order to satisfy human wants, which are unlimited. For the production of output to occur, resources (or inputs), which are limited, are required. Due to the limited nature of these resources and the unlimited nature of human wants – a situation giving rise to scarcity – a society is unable to fulfill all its desires. Therefore, choices must be made (in the society) as to which goods and services to produce, given limited resources.

Each of the sub-sections below outline important economic concepts and their applications to the old and new versions of Dunkirk (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958; Nolan, 2017). There are many scenes within the two versions of Dunkirk that illustrate the basic concepts of economics, such as those referenced above. In this chapter, we have selected what we believe are the most relevant and important of these concepts.

Inputs and outputs

Economic resources are inputs used in the production process to produce outputs, and are categorized into four groupings:

- Land, which encompasses natural resources.

- Labor, encompassing both quantity and quality, the latter of which is referred to as human capital and includes investments in education, training, experience, health, etc.

- Capital, which consists of tools, equipment, and buildings/structures.

- Entrepreneurs, which consists of individuals who obtain and organize resources for production.

Augmenting the above groupings is production technology, which refers to the process by which the economic resources outlined above are transformed into output.

In the Dunkirk movies (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958; Nolan, 2017), dominance and control over France was the goal of the war, or the output desired, from the German perspective. From the Allied perspective, a successful rear-guard action to save troops and equipment was the desired output. In order to produce these respective outputs, both the Germans and the Allied Forces required resources. The physical capital used in the war includes tanks, warships, boats, and fighter planes, among others. Labor includes the soldiers, officers, and other troops employed during the war. In order to be armed with a larger quantity of labor, the British recruited civilians, many of whom were unemployed and underprivileged youths, to their army. However, these soldiers were largely untrained or undertrained, leading to the British employing a low quality of labor or human capital. German troops, on the other hand, had much better human capital through their training and experience from recent campaigns in Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Belgium.8 The initial German victories on land have been attributed to the superior German panzers (compared to the French and Belgian tanks), as well as to the training and morale of its army. In economic terms, the Germans had better quality physical and human capital, all of which contributed to their successful advance through and eventual occupation of France.

Balancing this, the British Royal Air Force possessed superior fighter planes (compared to the Germans), as the air battle pitched the British Spitfire Mk1 against the German Messerschmitt Bf 109E. As Wood and Gunston (1977) indicate, “[i]t was over Dunkirk that the Messerschmitts first encountered the Spitfire … flown by resolute and skillful pilots; in combat with this nimble Royal Air Force Fighter, German pilots found that their own aircraft could be outturned,” a characteristic (i.e., a fighter’s turning ability) thought by many pilots as the sine qua non of dog fighting. Similarly, Spick (1996, 37) reports that “the maneuverability [of the Spitfire] was rather better [than that of the Messerschmitt], which came as a nasty shock to the German pilots.”9 This higher quality physical capital possessed by the British, combined with advancements in aerial radar (Editors, 1989), which extended from England well into France (Macdonald, 1986; Messenger, 1989), allowed the British to successfully keep the German forces from advancing to the port of Dunkirk until most Allied soldiers had been evacuated. In hindsight, the Germans’ “Halt Order” increased the quantity of labor hours available to the retreating Allied forces, which also enabled them to rescue more soldiers than originally anticipated.

Rational decisions (at the margin) and opportunity costs

Given that human wants are unlimited while economic resources are limited, society is forced to make tradeoffs whereby getting one thing requires giving up something else. Once a choice between the options has been made, the cost of the next best alternative of the choice that is made constitutes the opportunity cost of that choice. Thus, the opportunity cost is what is given up in order to acquire something. Economics also explains how rational decisions are made. Rational decision-makers think at the margin, weighing the marginal benefits against the marginal costs of any choice or decision. As such, marginal thinking refers to making decisions in increments. The decision-maker will then choose to pursue an action if its marginal benefits outweigh its marginal costs. Incentives (or disincentives) can alter the decision by affecting the benefits or costs. There are many scenes in Dunkirk (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958; Nolan, 2017) that illustrate these concepts, some of which we highlight below.

One wounded versus seven standing men

One of the early scenes in the second version of Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017) depicts British and French soldiers lining up while waiting to board a boat or ship to evacuate Dunkirk and return to Britain. A conversation between the Rear Admiral of the British Navy and the commander of the British ground forces takes place in which the commander is told to “decide how many more wounded to evacuate” given that “one stretcher takes the space of seven standing men” (Nolan, 2017). This is a clear example of how the Allies were faced with an opportunity cost owing to use of a limited resource, namely space on the evacuation fleet. The commander is then forced to face a tradeoff – at a rate of one to seven – between boarding wounded soldiers or healthy soldiers. Thus, in this scene the opportunity cost of boarding one wounded solider on a stretcher was seven healthy men (Nolan, 2017).

Many desperate soldiers, but inadequate space

In another scene (Nolan, 2017), the Rear Admiral and the commander contemplate the decisions to be made with regard to which soldiers of the Allied Forces are to be evacuated, due to the limited number of ships that were expected to arrive from Britain. The following is part of the dialogue (Nolan, 2017):

Commander: Where are the destroyers?

Rear Admiral: One should arrive soon.

Commander: What the Hell are they saving them for?

Rear Admiral: For the next battle – the one with Britain; same with the planes.

This dialogue shows how the warships and fighter planes of the British military were limited resources. The planes and warships would be categorized as physical capital for the military as they consist of the equipment used in producing the output of national defense. Due to the limited number of planes and warships, the British military faced a tradeoff between using them to evacuate the soldiers from Dunkirk and saving them for the anticipated German invasion of Britain.

The Rear Admiral goes on to state that “[Prime Minister Winston] Churchill wants 30,000, [Vice Admiral Bertram] Ramsay’s hoping we can give him 45,000,” when referring to the number of soldiers to be evacuated (Nolan, 2017). To this the commander replies, “there are 400,000 men on this beach, Sir” (Nolan, 2017). The Rear Admiral then states, “Well, we just have to do our best” (Nolan, 2017). With 400,000 troops needing to be evacuated and a limited number of ships expected at this time, the Rear Admiral is faced with a tradeoff as to how the limited naval resources will be allocated.

Survival of the fittest

The Rear Admiral is forced to make a rational decision by weighing the marginal benefits and marginal costs of allowing a wounded soldier on a stretcher to board the ships in lieu of seven healthy soldiers. The marginal benefits of boarding a wounded soldier would include getting the soldier back to England fast to get medical help and possibly save his life. However, the marginal costs would include not being able to get seven healthy soldiers back to Britain and the possibility that the wounded soldier would die even if he is boarded onto the ship. Therefore, the Rear Admiral is making the decision between possibly saving the life of a wounded soldier and evacuating seven healthy soldiers.

The Rear Admiral’s decision could depend on the probability of death of the wounded soldier, where the higher the probability of death, the higher the marginal cost of boarding this soldier on the ship. This decision would also depend on the necessity of the seven healthy soldiers to return to England, given that England was anticipating that Germany would attack her next. Finally, the additional weight of boarding seven healthy men versus one wounded man on a stretcher, which would influence the probability of the ship capsizing, should also be taken into account while making a rational decision. One can make an educated guess that the Rear Admiral would have made a rational decision to return the seven healthy soldiers in favor of one wounded soldier, particularly given that this example shows the importance of statistics in rational decision making.

Abandoning a sinking ship

Many scenes in both of the Dunkirk movies (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958; Nolan, 2017) portray the decisions made by the troops aboard ships as the ships are bombed by enemy planes. The soldiers made rational decisions as to whether to stay on a targeted ship or to abandon the ship and jump into the water. In doing so, they had to weigh the marginal benefits and marginal costs of jumping into the English Channel, as opposed to remaining on a targeted ship. While making their decision, in many cases they treated the sinking ship as a sunk cost – a cost that could not be recouped.

To jump or not to jump?

A couple of scenes in Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017) portray rational decision making by the pilots of the fighters and bombers. One such scene illustrated a pilot jumping out of his fighter after it was damaged by enemy fire. Clearly, the pilot was making a rational decision after weighing the costs and benefits of jumping out of the plane and into the English Channel, given that the probability of death was higher if his plane were to crash with him inside than if he were to jump into the water. Either way, the plane would be lost. Therefore, the pilot on the damaged plane thought about the plane as a sunk cost, just like the troops on the sinking ship. He did not factor the plane into his decision, while solely focusing on the decision to save his life.

Climb or go low?

As part of the air battle, one scene (Nolan, 2017) relates to a British bomber pilot making a decision whether to ascend to avoid being detected by the Germans or to stay low in order to conserve fuel. The pilot decided to ascend as the benefit of ascending (i.e., of not being detected by the Germans and consequently not dying from enemy fire) outweighed the cost (i.e., of using more fuel).

Drown or starve?

In the second version of Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017), a woeful soldier walks into the dangerous sea as he had given up being saved by the British ships. Sadly, he decided that the cost of death by drowning was less than the cost of dying a slow death on the beach without water and food.

Nothing better to do but to wait for the tide

The final scene in the second version of Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017) that we would like to highlight in this part of the discussion is one in which a few soldiers find a beached boat and decide to wait in it (for over three hours) for the tide to rise in order to be able to sail back to England. Given little else to do on the beach but wait, the opportunity cost of waiting three hours in the beached boat was low. Unfortunately, their gamble did not pay off because they were detected by the Germans and killed by gunfire.

Cruising the English Channel: not fair to the seasick, but maximizes resources

In economics, efficiency refers to getting the most that society can out of its limited resources, whereas equity refers to fairness. In the context of Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017), one could refer to the scenes in which the British captain of a private cruise boat volunteered the use of his vessel to transport soldiers back from Dunkirk. Given that the British faced a tradeoff between using their limited physical capital (ships) to evacuate a large number of soldiers from Dunkirk or to keep the ships in England for the anticipated German invasion, they chose the latter (Nolan, 2017). In order to ferry more retreating personnel from Dunkirk across the English Channel, a flotilla of private fishing and cruise boats was hastily assembled. In the scenes featuring the private cruise boat, the captain persisted in going to Dunkirk even though one of his crew members, a young boy, was dying on his ship (Nolan, 2017). In addition, he had also rescued an airman who later insisted that the captain turn back to Dover as he was very traumatized by being in the sea and did not want to return to the battlefront. However, the captain persisted in sailing back to Dunkirk. Hence, one can imply that there is a tradeoff between equity, being fair to the two ill people on the boat, versus efficiency – loading the boat to capacity with evacuated soldiers and making maximum use of the limited space on the boat.

Industrial organization and efficiency

Dunkirk (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958; Nolan, 2017) can also be analyzed from an industrial organization perspective. Industrial organization refers to how outcomes and decisions are influenced by market structure. For example, a monopoly exists when one entity has complete control of supply in an industry and it is insulated by barriers to entry. Monopolies fail to achieve either allocative or productive efficiency, whereas competitive firms/markets achieve both of these types of efficiencies in the long run.

Allocative efficiency: producing the optimal amount

Allocative efficiency results when the price of a good, which is a reflection of how much society values the good or is the benefit that society gets from an additional unit of the good, is equal to the marginal cost of the good, which is a measure of the sacrifice or cost to society of producing an additional unit of the good (i.e., marginal cost). Monopolies tend to under-produce and allocate insufficient resources toward the production of the good (i.e., price is greater than marginal cost). Allocative efficiency is achieved when resources allocated toward the production of an additional unit of the good are equal to how much society values an additional unit of the good (i.e., its price). Competitive firms tend to achieve allocative efficiency (i.e., price is equal to marginal cost); that is, the resources they allocate toward production are equal to the amount that society desires. Lastly, productive efficiency occurs when firms are utilizing the least-cost method of producing a good or service (i.e., firms are operating at the minimum of the average total cost curve).

Free entry and competition: not holding back anymore

In this respect, the British Navy originally held a monopoly on the supply of evacuation space. This in turn resulted in an under-allocation of resources toward providing enough space on ships for evacuees (i.e., price is greater than marginal cost). Later on during the evacuation, hundreds of private ships were either commissioned or volunteered to join the evacuation process, which resulted in the market structure changing from a monopoly to a more competitive environment. Thus, the characteristic of free entry led to a more competitive outcome. Moreover, through changing the structure of the market, the under-allocation of resources toward the production of the evacuation service was addressed, resulting in a move closer toward achieving allocative efficiency. It is worth pointing out that there were 366,000 waiting to be evacuated, and only 336,000 were ultimately rescued. This shows that an under-allocation of resources still existed. However, this number is higher than the number that would have been evacuated if the monopoly situation prevailed; based on the estimates by Churchill and Ramsey, that number would have been somewhere in between 30,000 and 45,000 (Nolan, 2017).

Supply and demand

Adam Smith, the father of modern economics and the author of the 1776 treatise titled An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, wrote about the efficiency of competitive markets in which an “invisible hand” coordinates the actions of many buyers and many sellers in order to reach the most efficient market outcome. According to Smith, while shortages and surpluses are possible in competitive markets, these shortages and surpluses are only temporary as markets correct themselves and produce an equilibrium.

Shortages: “He intends his own security … [but] is led by an invisible hand” (Smith, 1776)

In Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017), the quantity demanded of spaces on ships used to evacuate the soldiers was larger than the quantity supplied. There were 366,000 troops waiting to be evacuated. However, the British Navy only had a small number of warships available, representing a shortage of spaces on ships to accommodate the soldiers waiting to be evacuated. Given that the quantity demanded exceeded the quantity supplied, a shortage existed. As a result, the British Navy requested that private ship owners sail from England to Dunkirk in order to facilitate the evacuation of soldiers (Nolan, 2017). This increase in the number of ships increased the supply of evacuation spaces, which in turn reduced the shortage as there was room to accommodate around 336,000 soldiers, approximately 270,000 more than Churchill had anticipated would be evacuated (Nolan, 2017).

Asymmetric information: I know more than you

Asymmetric information refers to a situation in which one side in a conflict has more information than the other, providing it with an advantage in decision making situations. In applying this concept to the portrayal of the Battle of Dunkirk, we can state that, generally, the Germans had better information than the Allied forces. The panzer units, being the pride of the German land army, employed commanders that were equipped with superior communications technologies. Hence, there was better communication between German tank drivers and German unit commanders, who were traveling along with the advancing tanks.10 This asymmetric information advantage explains, at least in part, the swiftness of the German Army’s advance across the Low Countries and France, as portrayed in the early scenes of Dunkirk (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958; Nolan, 2017).

A battle for survival: a game theory approach

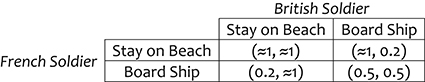

Here, we analyze the portrayal of the evacuation scenes in Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017) in the context of game theory. As the Germans were advancing and clearly winning the battle for France, continued fighting for Dunkirk would only result in the death of more Allied soldiers. By this time, Allied forces were fighting a losing war. The first value in each of the cells in the payoff matrix in Figure 6.1 represents the payoff to France in soldier deaths while the second value represents the payoff to Great Britain. If both England and the French give Dunkirk (and, thus, France) up to the Germans, the battle for Dunkirk would end and there would be no further deaths of soldiers related to this chapter of the war; thus, the (0,0) payoff to each, respectively, in the last cell of the payoff matrix. If both continue to fight for Dunkirk, there would instead be a payoff of (−1, −1) due to both countries losing soldiers.

Figure 6.1 Fight or abandon? A payoff matrix

If, on the other hand, one country abandons the beach while the other continues to fight for Dunkirk, the country which abandons Dunkirk suffers no additional soldier deaths, while the country that continues to fight the losing battle suffers a large negative payoff due to increasing soldier deaths from fighting a losing battle alone. As can be seen in the payoff matrix in Figure 6.1, the dominant strategy for both countries would be to abandon Dunkirk, as they both would be able to avoid additional soldier deaths. In Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017), it seems like the British arrived at this strategy before the French did.11 Once the British abandoned Dunkirk, the French conceded shortly thereafter due to their higher negative payoff of continuing to fight the war alone.

Cooperation versus self-interest: a game theory approach

Although the French and the British were allies in the war against Germany, many French soldiers were not allowed to board British ships and evacuate with British troops, even though British Prime Minister Winston Churchill announced that the soldiers would be leaving together “arm-in-arm.” In fact, there is a scene within the second version of Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017) that focuses on a French soldier, desperate to evacuate with the British, who is pretending to be a British soldier. Figure 6.2 depicts the strategic thinking of the individual British and French soldiers when they made their decisions as to whether to board the ships or stay in France. The numbers within the table represent the probability of death given certain actions. For example, if both evacuate together, the probability of death would be 50 percent. In this scenario, while both would be able to escape the advancing German Army, overcrowding of the ship would increase the risk of the ship not making the journey across the English Channel safely, eventually sinking and resulting in the death of some of the soldiers.

Figure 6.2 Abandon your ally or leave arm-in-arm? A payoff matrix

However, notice how this results in the best collective outcome as the collective probability of death for the Allied forces would be the lowest. If both the British soldier and the French soldier decide to stay in Dunkirk and not board the ship, the probability of death for each would be close to 1. If, on the other hand, one soldier decides to board the ship while the other soldier stays, the probability of death for the soldier who boards the ship can be approximated to be only 0.2; this results because, while there is some risk of death, this risk is reduced due to the lower likelihood of the ship capsizing with fewer people on board. In this situation however, the probability of death for the soldier who stays on the beach is close to 1. The dominant strategy for each individual soldier would be to board the ship.

Dunkirk (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958; Nolan, 2017) illustrates instances of conflict between cooperation and self-interest among British and French soldiers and the reason why cooperation is so hard to maintain in war situations. Cooperation is needed here so that every solder does not play his dominant strategy and, thus, capsize the vessels due to overcrowding. However, cooperation would require leaving behind many troops due to the lack of evacuation space among the rescue flotilla. Therefore, while collectively the Allied forces would have been better off if they had left “hand-in-hand,” each soldier’s self-interest results in them fighting for the limited spots on the ships as each soldier pursues his dominant strategy, with British soldiers succeeding. There is one specific scene (Nolan, 2017) in which a soldier on a capsizing boat was revealed to be French and was told to leave the ship by the other British soldiers in the boat – a scene that ties in particularly well with the scenario depicted in the payoff matrix in Figure 6.2. Lastly, another relevant scene in the second version of Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017) involves a conversation between the Rear Admiral and the commander, who are discussing the ratio of the British and French troops evacuating. Here, it is apparent that British self-interest dominated as Great Britain needed her army returned safely back home in order to prepare for the next battle – the expected German invasion of England. These examples show the break-down of cooperation in war situations as self-interest comes to the forefront.

Comparative advantage

An individual is said to have a comparative advantage over another individual or other individuals if he or she can produce a good or service at a lower opportunity cost. Dating back to the classical economics period, comparative advantage is one of the bases for mutual benefit in a free trade environment.

The lower opportunity cost option could save your life

The concept of comparative advantage can be better understood through an analysis of one of the early scenes in Dunkirk (Nolan, 2017). In it a British soldier, seeking to evacuate the beach, comes across a French soldier who is masquerading as a British soldier. Not wanting to give himself away, the French soldier offers his water to the British soldier. The opportunity cost to the French soldier of not offering water to the British solider could have been death on the beach when his identity was given away (given that the British were not currently boarding French soldiers onto their ships), whereas his opportunity cost of offering water to the British soldier is suffering additional thirst while waiting for his opportunity to board an evacuation ship and sail safely to England. In this scene the French soldier chose the lower opportunity cost option (Nolan, 2017). Even though this does not relate to trade between two parties, it’s useful to our understanding of how choosing the lower opportunity cost option can result in one being better off.

Opportunity cost and national security decisions

This final example relates to a previously outlined conversation between the commander and the Rear Admiral in which the Rear Admiral states that the fighter planes and destroyers were being kept in England to be used for the anticipated invasion of England by the Germans (Nolan, 2017). The opportunity cost of keeping most of the ships and planes in England was being unable to use them to evacuate around 400,000 troops, whereas the opportunity cost of sending these resources to Dunkirk was represented by the possibility of not having them available in order to protect England from the German invasion – a choice that might result in the death of millions of British soldiers and the loss of British home territory. Clearly, the opportunity cost of sending the ships and planes to Dunkirk was too high. The British military chose the lower opportunity cost option of keeping most of their resources in England (Nolan, 2017).

Conclusion

In this chapter we analyze the economics content of both versions of the well-known war movie titled Dunkirk (Divine and Lipscomb, 1958; Nolan, 2017), both of which cover the dramatic rescue of large portions of the Allied armies from destruction by the German Army near the beginning of World War II. Both movies present numerous examples of economic principles in a war situation. In providing our analysis of the economics content in these two movies, we have narrowed the discussion to specific examples of a few core economics principles. These include, but are not limited to, supply and demand, opportunity cost, economic resources, scarcity, rational decision making, the tradeoff between efficiency and equity, comparative advantage, and game theory. In providing the preceding analyses, our study extends the growing academic literature on economics in the movies.

References

Adler, T. 2017. “Dunkirk – A Stirring Blend of Documentary and Personal Sacrifice.” The Telegraph, July 13.

Ahlstrom, L.J. and F.G.Mixon, Jr. 2018. “Another Day, Another Vlog: The Alchian-Allen Theorem, Social Media, and Long-Distance Relationships.” Perspectives on Economic Education Research 11, 89–97.

Asarta, C.J., F.G.Mixon, Jr., and K.P. Upadhyaya. 2018. “Multiple Product Qualities in Monopoly: Sailing the RMS Titanic into the Classroom.” Journal of Economic Education 49, 173–179.

Becker, W.E. 2004. “Good-Bye Old, Hello New in Teaching Economics.” Australasian Journal of Economics Education 1, 5–17.

Bond, B. and H. Tuzo. 1982. “Dunkirk: Myths and Lessons.” The RUSI Journal 127, 3–8.

Burgess, C.A., F.G.Mixon, Jr., and R.W. Ressler. 2010. “Twitter and the Public Choice Course: A Pedagogical Vignette on Political Information Technology.” Journal of Economics and Finance Education 9, 43–49.

Burke, S., P. Robak, and C.F. Stumph. 2018. “Beyond Buttered Popcorn: A Project Using Movies to Teach Game Theory in Introductory Economics.” Journal of Economics Teaching 3, 153–161.

Crisp, A.M. and F.G.Mixon, Jr. 2012. “Pony Distress: Using ESPN’s 30for30 Films to Teach Cartel Theory.” Journal of Economics and Finance Education 11, 15–26.

Crowther, B. 1958. “Stern Look at Dunkirk: British Army Retreat Is Shown at Capitol.” The New York Times, September 11.

Divine, D. and W.P. Lipscomb. 1958. Dunkirk. London, UK: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Dixit, A. 2005. “Restoring Fun to Game Theory.” Journal of Economic Education 36, 205–219.

Editors. 1989. Lightning War. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books.

Formaini, R. 2001. “Free Markets on Film: Hollywood and Capitalism.” Journal of Private Enterprise 16, 123–129.

Leet, D. and S. Houser. 2003. “Economics goes to Hollywood: Using Classic Films and Documentaries to Create an Undergraduate Economics Course.” Journal of Economic Education 34, 326–332.

Macdonald, J. 1986. Great Battles of World War II. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Mankiw, N.G. 2018. Principles of Economics. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Mateer, G.D. 2004. Economics in the Movies. Mason, OH: Thomson-Southwestern.

Mateer, G.D. 2009. “Recent Film Scenes for Teaching Introductory Economics.” In F.G. Mixon, Jr. and R.J. Cebula (eds), Expanding Teaching and Learning Horizons in Economic Education. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers, pp. 165–172.

Mateer, G.D. and H. Li. 2008. “Movie Scenes for Economics.” Journal of Economic Education 39, 303.

Mateer, G.D., B. O’Roark, and K. Holder. 2016. “The 10 Greatest Films for Teaching Economics.” The American Economist 61, 204–216.

Mateer, G.D. and E.F. Stephenson. 2011. “Using Film Clips to Teach Public Choice Economics.” Journal of Economics and Finance Education 10, 28–36.

Mateer, G.D. and M.A. Vachris. 2017. “Mad Max: Traveling the Fury Road to Learn Economics.” International Journal of Pluralism and Economics Education 8, 68–79.

Messenger, C. 1989. The Chronological Atlas of World War Two. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Mixon, F.G., Jr. 1993. “Estimating Learning Curves in Economics: Evidence from Aerial Combat over the Third Reich.” Kyklos 46, 411–419.

Mixon, F.G., Jr. 2010. “More Economics in the Movies: Discovering the Modern Theory of Bureaucracy in Scenes from Conspiracy and Valkyrie.” Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research 11, 101–113.

Mixon, F.G., Jr., C.J. Asarta, and S.B. Caudill. 2017. “Patreonomics: Public Goods Pedagogy for Economics Principles.” International Review of Economics Education 25, 1–7.

Mixon, F.G., Jr. and R.J. Cebula. 2014. New Developments in Economic Education. Cheltenham, MA: Edward Elgar.

Nolan, C. 2017. Dunkirk. Los Angeles, CA: Warner Brothers.

Samaras, M. 2014. “Learn Economics by Going to the Movies.” Journal of Education and Human Development 3, 459–470.

Sankaran, C. 2019. “The Choice Is Yours: You Can Win With This, or You Can Win With That.” Research paper presentation at the Annual Allied Social Science Associations (ASSA) Annual Meetings,

Sankaran, C., D. Corcoran, and T.Mulroney, Jr. 2016. “An Exercise on Creating a Student Expenditure Basket.” Journal of Economics Teaching 1, 90–110.

Sankaran, C. and T. Sheldon. 2017. “Counting Cars: A Sustainable Development Experiential Learning Project.” Presentation at the American Economic Association’s (AEA) National Conference on Teaching and Research in Economic Education (CTREE), Denver, Colorado.

Sexton, R. 2006. “Using Short Movie and Television Clips in the Economics Principles Class.” Journal of Economic Education 37, 406–417.

Smith, A. 1776. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell.

Spick, M. 1996. Luftwaffe Fighter Aces: The Jagdflieger and their Combat Tactics and Techniques. New York, NY: Ivy Books.

Summerfield, P. 2010. “Dunkirk and the Popular Memory of Britain at War, 1940–58,” Journal of Contemporary History 45, 788–811.

Sutter, M. 2012. Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films during World War II. Master’s Thesis, Ontario, Canada: Lakehead University.

Wood, T. and B. Gunston. 1977. Hitler’s Luftwaffe. London, UK: Salamander Books Ltd.