During the course of World War II, more than 250,000 aircraft battled for supremacy of the air over western Europe, and nearly 200,000 air-crewmen lost their lives in the process (Merrick, 1990). In order to mitigate the fatalistic outlook that almost certainly developed among the 10 U.S. air-crewman aboard the typical B-17 Flying Fortress and other bombers in the United States Air Force (USAAF), bomber flight crews were relieved of their combat responsibilities upon completion of their 25th air mission. One such successful crew, that of the famed Memphis Belle, flew its 25th and final mission on May 17, 1943 (Merrick, 1990). That harrowing flight is commemorated in the movie Memphis Belle (Merrick, 1990), which was released in 1990.1 The movie also depicts, in a wartime context, a few of the core concepts of economics. These are the focus of this chapter.

Production possibilities and the strategic bombing of Nazi Germany

After losing World War I (WWI), Germany found itself in a state of reduced production capacity due to the casualties incurred during its prosecution of the war. The population decline resulting from the war caused a decrease in Germany’s production possibilities, as there were fewer labor inputs that could be employed in the overall process of production. Compounding this reduction in the labor force is the fact that in January of 1923 France and Belgium seized all of the industry and mines in the Ruhr after Germany failed to deliver 140,000 telephone poles as part of its reparations requirements under the Treaty of Versailles (Editors, 1990, 124 and 128).

The production possibilities frontier (PPF) in Figure 7.1 reflects the reduced production capabilities of Germany in the early 1920s, which were exacerbated by the fact that Germany financed WWI through debt, rather than through taxation. This, combined with the cost of demobilization, led to chronic post-WWI deficits (Editors, 1990, 124). To address this predicament, the government printed money, a process that gained pace in April of 1921, when the Allies presented their war reparations bill which, under the Treaty of Versailles, called for annual payments of 132 billion marks indefinitely.2 As expected, the expansionary monetary policy adopted by Germany led to hyperinflation (Braun, 1990), which soon forced businesses to pay their employees daily, even twice a day, so they could hurry to buy food before prices doubled again (Editors, 1990, 129). This type of activity represents a compelling example of how runaway inflation leads to a substitution of inflation-avoiding activity for productive activity.3

Figure 7.1 Germany’s PPF, early 1920s–early 1930s

The point, ❶, located inside the PPF depicted in Figure 7.1 represents Germany’s production point in the early 1930s, as (1) influenced by the production details discussed above, (2) mandated by the features of the Treaty of Versailles, and (3) impacted by the economic consequences of the Great Depression. To prevent the country from threatening its neighbors militarily, the Treaty of Versailles limited Germany’s army to 100,000 men and prohibited the production of tanks and poison gas (Levy, 2006). Germany’s air force was dissolved and its navy was limited to only 15,000 sailors, six battleships, and 30 smaller vessels. Additionally, the German Navy was prohibited from maintaining a fleet of submarines (Levy, 2006). Thus, through the various provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, the Allied nations (e.g., England, France, United States, etc.) were able to force the German economy to focus mostly on civilian goods, which are represented in Figure 7.1 by “butter,” and not on military goods, which are referred to in Figure 7.1 as “guns.” The placement of ❶ further along the axis labelled “Butter” than along the axis labelled “Guns” reflects the mandates of the Treaty of Versailles.

By the early 1930s, the Great Depression had ushered in massive waves of unemployment around the globe. During the six months ending in March 1931, unemployment increased by more than 50 percent, to 4.75 million people (Editors, 1989a, 82–83). The German government temporarily closed all German banks in July of 1931 after two large bank failures. Emergency decrees raised taxes, lowered wages, and reduced unemployment benefits (Editors, 1989a, 82–83). By the beginning of the 1932 political season in Germany, six million Germans were registered as unemployed (Editors, 1989a, 40). As a result, Germany’s production point, ❶, is placed well inside its PPF in Figure 7.1, rather than on or very near it.

The National Socialists, or the Nazi party, rose to power in Germany in the first half of the 1930s and began a reversal of the austerity policies of the previous decade. Construction of the German autobahn began during that time – a project that would ultimately create 2,000 miles of four-lane highways by 1938 – generating construction work for tens of thousands of unemployed men and stimulating growth in Germany’s fledgling automobile industry (Editors, 1989b, 145). The newly-created Reich Labor Service, which required six months of service for all males between the ages of 18 and 25, generated additional production in farming and construction (Editors, 1989b, 145). By the spring of 1936, only 1.8 million Germans were unemployed, a situation that improved even further – to near-full employment – during 1937 (Editors 1989b). This trend was helped along by the Four Year Plan of 1936, which focused on agricultural autarky and production of synthetic versions of resources that Germany lacked (Braun, 1990).

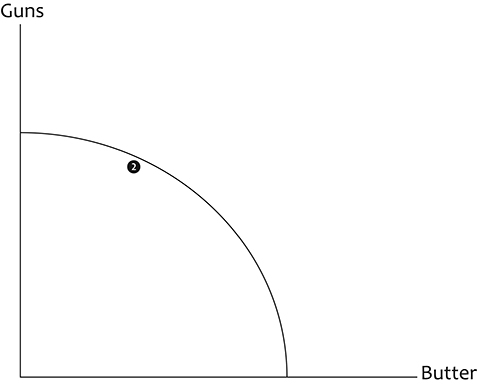

Germany’s economic boom of the late 1930s was also the product of its secretive efforts at rearmament (Abelshauser, 1998), which began in 1936 and ultimately absorbed all of the remaining one million unemployed workers during 1936 and 1937, such that by 1938 the country was experiencing a worker shortage of roughly one million, which was filled by importing foreign workers (Editors, 1989b, 147 and 154). It is important to note that the process described here and in the preceding paragraphs began in an underutilized economy, and that the new emphasis was on “guns” and not “butter,” further allowing the German economy to grow in the lead up to World War II. The expanded PPF for Germany in August of 1939 that is shown in Figure 7.2 demonstrates the growth of Germany’s economy in the lead up to World War II, while the placement of Germany’s production point, ❷, therein is indicative of the country’s near-full employment situation and its newfound focus on military goods (i.e., “guns”) over consumer goods (i.e., “butter”).

Figure 7.2 Germany’s PPF, August 1939

World War II began in early September of 1939, with Germany’s invasion of Poland. In response, Great Britain and France honored a commitment to Poland and declared war on Germany. After conquering Poland in a few weeks, Germany would conquer Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Norway, and France during the first half of 1940. Germany would realize further success in 1941 by conquering Yugoslavia and Greece, setting up its June of 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. As its forces stalled at the outskirts of Moscow, Germany’s Axis partner, Japan, executed a surprise attack on the United States in early December of 1941. Shortly thereafter, German dictator Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States.

Shortly after entry into World War II, the USAAF began setting up air bases in England in order to prosecute a strategic bombing campaign against Nazi Germany. Evidence of the effectiveness of the Allied strategic air campaign against Germany is offered in the memoirs of Albert Speer, Nazi Germany’s Minister of Armaments. As Speer (1970, 284–285) recounts, an August 17, 1943, raid on German ball bearing plants in Schweinfurt by the USAAF reduced Germany’s production of ball bearings to only 62 percent of its July 1943 level, causing the country to exhaust all of its ball bearing stores over the following six to eight weeks. A follow-up raid on October 14, 1943, reduced ball bearing production to only 33 percent of its July 1943 level, while an additional raid in February of 1944 succeeded in reducing Germany’s ball bearing production to only 29 percent of its July 1943 level (Speer, 1970, 285–286).

Speer (1970) recounts a similar story with regard to Germany’s production of aircraft fuel. As he indicates (Speer, 1970, 346), a USAAF raid on Germany’s fuel plants introduced a “new era” of the war by reducing Germany’s daily production of aircraft fuel to 4,820 metric tons, down from 5,850 metric tons per day prior to the raid. After 16 days of repairs, bringing daily production back up to 5,850 metric tons, a second attack on May 28–29, 1944, succeeded in reducing German fuel production to 2,925 metric tons per day (Speer, 1970, 348). An additional attack on June 22, 1944, brought production of aircraft fuel down to 632 metric tons per day, although repairs succeeded in bringing daily production back up to 2,307 metric tons by July 17, 1944. Four days later, however, USAAF raids struck again, this time reducing production to only 120 metric tons per day, after which Speer (1970, 350) points out that the German economy was triumphant whenever daily production reached 10 percent of it prior level of 5,850 metric tons per day.

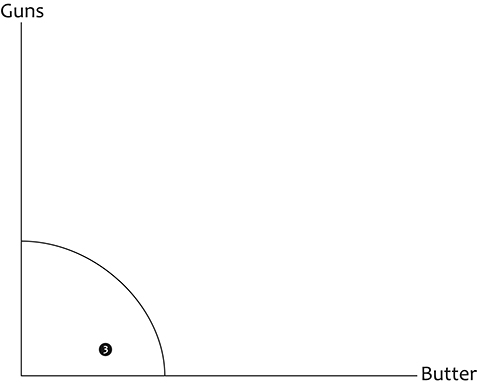

The Allied bombing campaign described above continued through the end of the war, leaving Germany impoverished and at an economic standstill. The war had decimated German land, buildings, infrastructure, and lives (Abelshauser, 1998; Braun, 1990), while it had also created an energy crisis (Braun, 1990). The PPF in Figure 7.3 shows Germany’s reduced production capacity at the end of World War II. Not only had production capabilities overall decreased, as indicated by the position of the PPF in Figure 7.3 relative to that in Figure 7.2, the economic standstill meant that Germany was producing inside of its production capabilities due to the devastation wrought by World War II.

Figure 7.3 Germany’s PPF, May 1945

In the section of this chapter that follows, we discuss some of the mechanics of the USAAF’s conduct of the strategic bombing campaign against Hitler’s Germany. Those mechanics center around the USAAF’s use of the B-17 Flying Fortress – the backbone of the strategic air war over Nazi Germany – and how operation of such an instrument of war involves the concepts of division of labor and specialization that Adam Smith discussed in his now-famous treatise on economics.

Division of labor and specialization in a Flying Fortress

The concepts of specialization and division of labor are generally associated with the eighteenth-century writings of Scottish economist Adam Smith. Smith begins his famous treatise (Smith, 1776: 13) by asserting that specialization and division of labor have resulted in the greatest advancement in the productivity of labor. His now well-known example of the pin factory describes how the work is divided into distinct trades, such that one worker “draws out the wire,” another “straight[en]s it,” a third worker “cuts it,” another “[sharpen]s it,” a fifth “grinds it at the top for receiving the head,” and so on, while additional workers perform the distinct tasks of making the head (Smith, 1776: 14–15). In all, Smith (1776: 15) is able to quantify “about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some [pin factories], are all performed by distinct hands.”

The 1944 edition of the USAAF’s Pilot Training Manual for the B-17 Flying Fortress provides a blueprint of the type of specialization and division of labor discussed by Smith (1776) in describing the manufacture of pins. The B-17 Flying Fortress was manned by a crew of 10, including the pilot and the co-pilot. The main responsibilities of each are listed in Table 7.1. As noted there, the pilot is considered the commander of the aircraft, and in addition to piloting it to its destination and back, he is charged with commanding a crew that, in the Smithian sense, “is made up of specialists” (USAAF, 1944).4 Among these specialists are the aircraft’s navigator, who, according to USAAF (1944), is tasked with directing the flight from departure to destination and return, a process that involves proficiency in geographic positioning via pilotage (i.e., determining position by visual reference), dead-reckoning (i.e., basis for all types of navigation), radio (i.e., determining position by radio aids), and celestial (i.e., determining position by reference to two or more celestial bodies).

Table 7.1 Responsibilities of the B-17 Flying Fortress crew

| Crew member | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Pilot | Commander, flies the plane and commands the crew, which “is made up of specialists.” |

| Co-pilot | Executive officer, capable of flying plane, proficient in engine operation, knowledgeable of cruising control data, capable aircraft engineer and navigator. |

| Navigator | Directs flight from departure to destination and return, a task involving proficiency in geographic positioning via pilotage (i.e., determining position by visual reference), dead-reckoning (i.e., basis for all types of navigation), radio (i.e., determining position by radio aids) and celestial (i.e., determining position by reference to two or more celestial bodies). Also responsible for instrument calibration, pre-flight planning, post-flight critique and proficiency in operation of the top turret gun. |

| Bombardier | Directing an accurate and successful bombing mission, which involves proficiencies in bomb-sighting, auto-piloting, target identification, and solving various bombing problems involving altitude, air speed, bomb ballistics, trail, time of fall, groundspeed, and drift. |

| Radio operator | Operation of radio equipment, which involves mastery in radio, instrument landing, IFF [identification, friend or foe], and VHF [very high frequency]. Also mans a machine gun and executes reconnaissance photography. |

| Engineer | Maintain proper functioning of all operating systems in or on board the aircraft and proficiency in operation of the top turret gun. |

| Turret gunners | Familiarity with mechanics and coverage area of gun platforms, proficiency in aircraft identification, and effective use of inherent flying ability. |

| Flexible gunners | Familiarity with mechanics and coverage area of gun platforms, proficiency in aircraft identification, and familiarity of exterior ballistics. |

Source: USAAF (1944).

Next is the bombardier, whose job is directing an accurate and successful bombing mission, which involves proficiencies in bomb-sighting, auto-piloting, target identification, and providing various bombing solutions involving altitude, air speed, bomb ballistics, trail, time of fall, groundspeed, and drift (USAAF, 1944). The radio operator is tasked with the operation of radio equipment, which involves mastery in radio, instrument landing, IFF, and VHF. The Flying Fortress’ engineer maintains proper functioning of all operating systems in or on board the aircraft and is proficient in the operation of the top turret gun, a skill that is essential when enemy fighters are harassing the bomber formation (USAAF, 1944). Finally, the turret gunners (ball and top) must be familiar with the mechanics and coverage area of their gun platforms, which, in the case of turret-operated platforms, requires what the USAAF (1944) refers to as effective use of inherent flying ability. Similarly, the flexible gunners (waist and tail) must be familiar with the mechanics and coverage area of their gun platforms, which requires a familiarity of exterior ballistics (USAAF, 1944).

The discussion above describes, using original source material, the operation of the USAAF’s B-17 from a historical perspective. In the section that follows, operation of a B-17 is brought to life through a review of Hollywood’s portrayal of the air war over Europe in the movie Memphis Belle. In presenting this review, we highlight the core economic concepts discussed first in 1776 by Scottish economist Adam Smith – division of labor and specialization.

The core concepts of economics take flight in Memphis Belle

The names of the actual airmen who crewed the Memphis Belle are listed, along with their positions on the bomber, in Table 7.2. Also listed there are the names of the actors, and the names of their movie characters, who portrayed the actual crewmen in Memphis Belle. As their final flight begins, the various specialties of the crewmen come to life through the dialog and actions of the main characters in the movie. The final flight scene provides an excellent example of Smith’s notions of specialization and division of labor. Shortly after takeoff, the bombardier, Val Kozlowski, requests permission to arm the bombs (Merrick, 1990). After arming the bombs, Kozlowski reports back to the pilot, Dennis Dearborn, that the bombs are armed. At about the same time, the plane’s engineer, Virgil Hoogesteger, assists Richard Moore in mounting the ball turret, who ensures that it is operational (Merrick, 1990).

Table 7.2 Crew members of Memphis Belle

| Crew member | Name | Movie character | Portrayed in movie |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot | Robert Morgan | Dennis Dearbon | Matthew Modine |

| Co-pilot | James Verinis | Luke Sinclair | Tate Donovan |

| Navigator | Charles Leighton | Phil Lowenthal | D.B. Sweeney |

| Bombardier | Vincent Evans | Val Kozlowski | Billy Zane |

| Radio operator | Robert Hanson | Danny Daly | Eric Stoltz |

| Engineer | Harold Loch | Virgil Hoogesteger | Reed Diamond |

| Turret gunners | Cecil Scott | Richard Moore | Sean Astin |

| Flexible gunners | Casimer Nastil John Quinlan Clarence Winchell | Jack Bocci Clay Busby Eugene McVey | Neil Giuntoli Harry Connick, Jr. Courtney Gains |

Sources: IMDb.com; National Museum of the U.S. Air Force (nationalmuseum.af.mil).

By this time in the mission the Memphis Belle is cruising at an altitude of 10,000 feet. Luke Sinclair, the co-pilot, calls for the crew to deploy oxygen. Shortly thereafter, the navigator, Phil Lowenthal, reports to Dearborn that the bombing group is exactly five miles south/southwest of Great Yarmouth near the English coast, which is the mission rally point (Merrick, 1990). Just after they reach the rally point, Dearborn alerts the crew to “keep your minds on your jobs, work together, and stay alert” (Merrick, 1990). As the mission continues, Dearborn reports to the crew that the temperature is −30° Fahrenheit, and he reminds the crewmen to avoid touching the gun platforms and to keep checking their oxygen masks for frozen saliva. He also adds that the intercom should be kept free, and that German fighters should be called out as they are spotted (Merrick, 1990). Here, each character performs a different task, displaying how specialization and division of labor ensures productive outcomes.

As the bomber group approaches mainland Europe, Dearborn orders the crew to test the guns, at which point each crewman fires a short burst into the open sky. At this point, Hoogesteger informs the crew that a group of USAAF fighters are escorting, at three o’clock high, the bomber formation (Merrick, 1990). Later, when the first air-to-air combat sequence commences, the crewmen are heard calling out enemy fighter locations, as Dearborn instructed. During the melee, the lead bomber was damaged and withdrew from the mission. The radio operator of the new lead bomber contacts Danny Daly, the radio operator of the Memphis Belle, to inform him of this latest development (Merrick, 1990).

As the mission progresses, Dearborn calls on Lowenthal to report the bomber group’s location. Lowenthal soberly informs the air-crew that it is officially in the airspace of the Third Reich. At this point, the second air-to-air melee begins (Merrick, 1990). During this confrontation, the replacement lead bomber is damaged and drops out of the formation, leaving Memphis Belle as the new lead bomber. Dearborn instructs Daly to connect his radio to the entire bomber force, after which Dearborn instructs the force that Memphis Belle is the lead bomber and that its crew will do its best to put the bomb load “right in the pickle barrel,” which is Dearborn’s oft-used phrase for the pursuit of bombing accuracy (Merrick, 1990). Dearborn then instructs the formation that it is 3 minutes and 30 seconds from the bomb run.

At this point, the third air-to-air engagement begins, during which Moore reports that the ball turret is jammed. Hoogesteger, the bomber’s engineer, leaps into action to assist Moore, only to learn that the jam is a false alarm (Merrick, 1990). Then, waist gunner Jack Bocci takes what turns out to be a superficial wound from the machine gun of an enemy fighter.5 In response, Dearborn instructs Kozlowski to render medical aid, but is forced to call another crewman to assist Bocci given that Kozlowski is prepping the bombing run over Bremen (Merrick, 1990). Once again, division of labor allows all of the crew members to successfully work together.

As the bomber group nears Bremen, an intense flak barrage, from what co-pilot Sinclair reports are about 500 anti-aircraft guns, greets it (Merrick, 1990). Dearborn instructs the crew to don flak jackets, and then informs Kozlowski that the bomber is on autopilot and that he (Kozlowski) is in control of the bomber until the bombs are dropped. Shortly thereafter, a flak burst damages one of the bomber’s wings, causing a fuel leak. Hoogesteger again leaps to action (assisted by Sinclair), in this case manually operating the fuel transfer pump (Merrick, 1990). During this scene, Kozlowski opens the bomb bay doors in preparation for the bombing run.

Kozlowski reports to Dearborn that his view of the Messerschmitt assembly plant is obstructed by a large smokescreen. Dearborn then turns off the autopilot and informs the bomber group that it is turning around for a second run.6 As the second run begins, Dearborn again informs Kozlowski that the bomber is on autopilot and that he (Kozlowski) is in control of the bomber until the bombs are dropped (Merrick, 1990). At the final second of this run, the target is unobscured and the bomb load is successfully dropped on the assembly plant. Kozlowski then closes the bomb bay doors as Dearborn and Sinclair put the formation into an evasive action posture in order to avoid further flak damage (Merrick, 1990). The bombing of the German factory by the Memphis Belle crew provides an example of how Allied forces successfully decreased Germany’s production capabilities, as displayed in Figure 7.3.

On the return to England, a machine gun burst from a German fighter both wounds Daly and causes an onboard fire. As members of the crew provide medical aid to Daly, a burst from an enemy fighter causes a fire in engine four. With a disabled fire extinguisher, Dearborn and Sinclair put the Memphis Belle into a steep dive in order to save the plane (Merrick, 1990). The skill of the two pilots extinguishes the fire and saves the bomber, which limps back to its airbase in England.

Conclusion

Memphis Belle depicts the famed B-17 Flying Fortress of the same name in its successful twenty-fifth and final mission to bomb a German factory. The scenes discussed in this chapter display examples of Adam Smith’s ideas of division of labor and specialization, as well as the reduction of Germany’s production possibilities. The crew aboard the aircraft exhibits how well dividing up tasks and specializing in specific roles leads to better outcomes, such as a successful bombing mission. The success of the mission culminates in the destruction of German infrastructure, thus damaging Germany’s production capabilities and reducing its production possibilities frontier. The Memphis Belle’s mission in the film shows the destruction of war, but it also demonstrates how labor working together can produce efficient results.

References

Abelshauser, W. 1998. “Germany: Guns, Butter, and Economic Miracles.” In M. Harrison (Ed.), The Economics of World War II. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Braun, H.J. 1990. The German Economy in the Twentieth Century. London, UK: Routledge.

Editors. 1989a. Storming to Power. New York, NY: Time-Life Books.

Editors. 1989b. The New Order. New York, NY: Time-Life Books.

Editors. 1990. The Twisted Dream. New York, NY: Time-Life Books.

Levy, M. 2006. “The Treaty of Versailles.” Encyclopedia Britannica. London, UK: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc.

Merrick, M. 1990. Memphis Belle. Los Angeles, CA: Enigma Productions and Warner Bros.

Smith, A. 1776. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Book I). Liberty Classics Reprint, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Speer, A. 1970. Inside the Third Reich. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company.

USAAF. 1944. Pilot Training Manual for B-17 Flying Fortress. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.