“The law of an organized or psychological crowd is mental unity. The individuals composing the crowd lose their conscious personality under the influence of emotion and are ready to act as one, directed by the low crowd intelligence.”

—Thomas Templeton Hoyle

“In any case, regardless of our political leanings, we should remember that the job of a contrarian is to challenge those beliefs that we hold most dear—the very beliefs that, because of our loyalty to them, we are least likely to subject to critical scrutiny.”

—Mark Hulbert, July 25, 2012, MarketWatch

Humphrey Neil put together his own ideas and experience and joined them with the writings of Charles Mackay (Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds), Gustav Le Bon (The Crowd), and Gabriel Tarde to form the theory of contrary opinion. Today, it is widely understood that since the “crowd” is wrong at major market turning points, the only game in town is to be a contrarian! Unfortunately, whenever a concept or theory becomes popular, the basic idea is often distorted. This means that those who have taken the theory on its face value and not taken the trouble to study Neil and other writers are probably on shaky ground.

Neil pointed out that the crowd is actually correct for substantial amounts of time. It is at turning points that the majority get things wrong.

This last idea is really the center to Neil’s thinking. Once an opinion is formed, it is imitated by the majority until virtually everyone agrees that it is valid. As Neil (1980) put it, “When everyone thinks alike, everyone is likely to be wrong. When masses of people succumb to an idea, they often run off at a tangent because of their emotions. When people stop to think things through, they are very similar in their decisions.”

The word “think” has been deliberately emphasized because the practice of contrary opinion is very much an art and not a science. To be a true contrarian, you need to study, be patient, be creative, and bring to the table widespread experience. Remember, no two market situations are ever identical because history may repeat, but it rarely repeats exactly. In effect, it’s not as easy as saying, “Everyone else is bearish; therefore, I am bullish.”

Perhaps the best definition of contrary opinion comes from the late John Schultz, who, in a timely bearish article in Barron’s just prior to the 1987 crash wrote, “The guiding light of investment contrarianism is not that the majority view—the conventional, or received wisdom—is always wrong. Rather, it’s that the majority opinion tends to solidify into a dogma while its basic premises begin to lose their original validity and so become progressively more mispriced in the marketplace.”

Three words have been emphasized because they encapsulate the three prerequisites of forming a contrary opinion. First, the original concept solidifies into a dogma. Second, it loses its validity and a new factor or series of factors comes into play. Finally, the crowd moves to an extreme, as reflected in a gross overvaluation. What he is saying is that at the start of a trend a few far-seeing individuals anticipate an alternative scenario or outcome to that being promoted by the majority. Later, as prices rise, others are persuaded that the scenario is valid. Then, as the trend extends, more and more people join the camp, perhaps being persuaded as much by the rising prices as the concept itself. Eventually, the concept or premise becomes a dogma so that everyone accepts it as gospel. By now, though, it has been so well discounted or factored into the price that the security or market in question is way overvalued. Even if the price is not overvalued, the concept begins to lose its original premise and a new scenario emerges. All those betting on the original one lose money as the market reverses to the downside.

These trends occur because investors tend to move as crowds and are subject to herd instincts. If left to their own devices, individuals isolated from their peers would tend to act in a far more rational way. Say, for example, you see stock prices starting to move up sharply after they had already moved up a lot. Even though you might know from your own experience that they cannot continue to go up forever, it would be difficult not to become caught up in the excitement, especially after they had rallied significantly from the level at which you first thought them irrationally high. Under such an environment it becomes very difficult to think independently from the accepted wisdom of the day.

Neil wrote that there are several what he calls social laws that determine crowd psychology. These are as follows:

1. A crowd is subject to instincts that individuals acting independently would never succumb to.

2. People involuntarily follow the impulses of the crowd. (see the later section on why it is difficult to go contrary).

3. Contagion and imitation of the minority make individuals susceptible to suggestion, commands, customs, and emotional appeals.

4. When gathered as a group or crowd, people rarely reason or question, but follow blindly and emotionally what is suggested or asserted to them.

Why then is the crowd wrong at turning points? The reason is that when everyone holds the same bullish opinion, there is very little potential buying power left and very few people left who can perpetuate the trend. By the same token, if the market is mispriced, to quote John Schulz, other investment alternatives are becoming more and more attractive—little wonder that money soon flows from the overvalued, overbelieved situation to the more realistically priced one. The opposite would, of course, be true in a declining trend.

Take, for example, an economy deep in recession, business activity is declining rapidly, and layoffs and high unemployment are getting headlines in the nightly news. Stocks are extending their decline that began over a year ago, and the whole situation appears to be out of control in a self-feeding spiral. While everyone is looking down, it is the prerequisite of the contrarian to look up and ask the question, “What could go right?” This is where the alternative scenario comes in. Remember, people are rational. When they realize that hard times are coming, they adjust their plans accordingly. Businesses will cut excessive inventories, lay off workers, and pay off debts. Once this has been done, break-even points drop and businesses are in a great position to increase profits when the economy turns. All this economizing means that the demand for credit declines and so does its price—interest rates. Falling rates encourage consumers to go out and buy houses, and a new recovery gets underway. As Neil describes it, “In historic financial eras, it has been significant how, when conditions were slumping that, under the pall of discouragement, the underlying economics were righting themselves underneath to the ensuing revival and recovery.”

The same is true in markets. No one is going to hold stocks if they think prices are in for a prolonged decline, so they sell. When all the selling is over, there is only one direction in which prices can go, and that’s up! At that point, true contrarians have decided that enough is enough and that an alternative bullish outcome is likely and the underlying assumptions of the bear market are no longer valid.

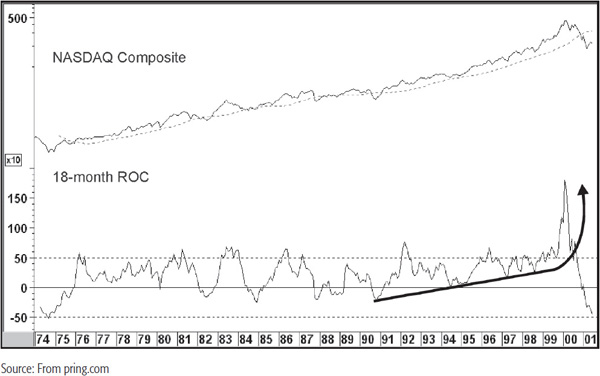

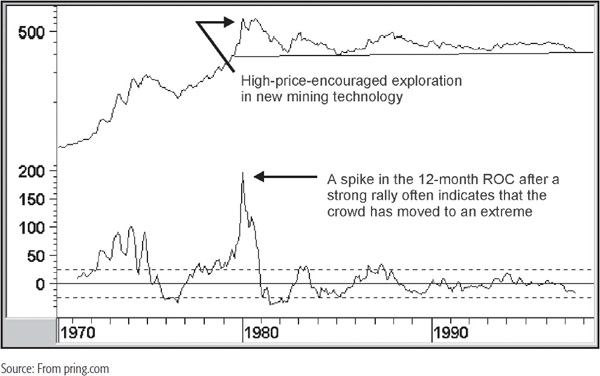

Knowing when to go contrary is a key to the whole process because the crowd frequently moves to extremes well ahead of a market turning point. Many professionals knew the situation was getting out of hand in 1928 and in 1999 (for Internet stocks). In both cases, they had concluded that stocks were way overvalued and were discounting the hereafter. These opinions were correct, but their timing was early. Economic trends are often slow to reverse, and manias take prices well beyond reasonable valuations, often to ridiculous and irrational ones. In a sense, crowd psychology can be reflected graphically as a long-term oscillator, such as a rate of change (ROC) that moves to extraordinary levels not seen for decades. In normal times, a market turns when the indicator reaches its overbought level, but on rare occasions, the curve can run up to stratospheric levels. An example is shown in Chart 30.1 for the NASDAQ. The 18-month ROC in the lower panel moves up to a level dwarfing anything seen in the previous 20 years of trading history. Indeed, it was twice as high as the best reading for the S&P Composite in 200 years of history.

CHART 30.1 NASDAQ Composite, 1974–2001, and an 18-Month ROC

If crowd sentiment is reflected in oscillators constructed from the price, then it follows that there are various levels or extremes to which crowds gravitate. The 1999 peak in the NASDAQ, the 1980 top in gold, and the 1929 peak are all examples of an extreme. However, since oscillators can be constructed from daily and weekly data, it follows that forming a contrary opinion is just as valid for shorter-term turning points. The difference is that the mood is not so all encompassing and intense as it is just prior to the bursting of a financial bubble.

Bearing these comments in mind, it is now time to examine the kinds of signs that indicate when the crowd has moved to an extreme, either for small or large trends, and then see how technical analysis can be applied to such situations.

Reading and learning about forming a contrary opinion is one thing, but actually applying it in the marketplace when your money is on the line is completely another. There are several reasons why it is not easy to take a position that is opposite to the majority:

1. It is very challenging for us to take an opposite view from those around us because of our need to conform.

2. If prices are rising sharply and we have already told friends of our reasons for being bearish, we are unlikely to continue in our contrarianism out of a fear of being ridiculed.

3. We often meet hostility when we go against the crowd.

4. There is always a tendency to extrapolate the past, from which we gain a sense of comfort.

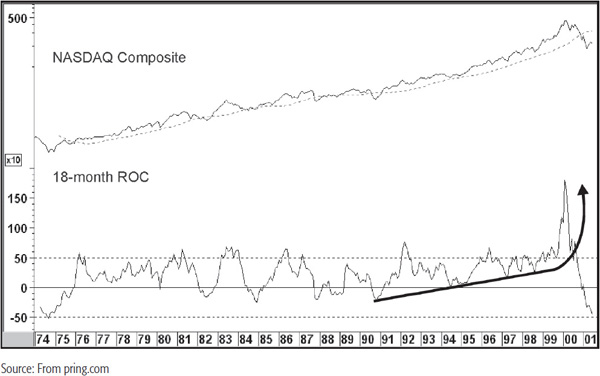

5. A certain sense of security can be had from accepting the opinions of “experts” instead of having the confidence to think for ourselves. Chart 30.2 illustrates several quotations that three famous people probably wish they had never made. Never forget that most “experts” have a vested interest in the opinions they give publicly.

CHART 30.2 The S&P Composite, 1921–1935, and Market Comments

6. We tend to believe that the establishment has all the answers. The United States’ entry into Vietnam, the Soviets’ into Afghanistan, and Neville Chamberlain’s famous “peace in our time” speech just before the outbreak of World War II should make us think twice about this assumption.

The first step is to try and get a fix on the consensus opinion of the market or individual security being monitored. If the crowd is not at an extreme, nothing can be done because we are only concerned with identifying potential trend reversals when crowd psychology has swung sharply in one direction or another. Bear in mind that the crowd is often right during a trend—it’s at the turning point that the herd is almost always wrong. One method of gauging where the majority of market participants lie in their opinion is to refer to the sentiment indicators discussed in the previous chapter, or even an oscillator. Most of the time, these indicators are not telling us very much, but when they reach an extreme, a strong message is being given. Another possibility is to monitor valuations. If they are within the accepted norm, then there is little to be learned, but if they are approaching an extreme, then the crowd is giving us a valuable clue as to the way it is leaning.

Alternatively, a study of the media—particularly the financial media—can inform us of what people are thinking. If there is no clear-cut view, then there is not likely to be an extreme and there is little to be done.

However, as it becomes clear that a general consensus is forming and that consensus is approaching a dogma, it is then time to begin the creative process by thinking in reverse, and that involves the second step.

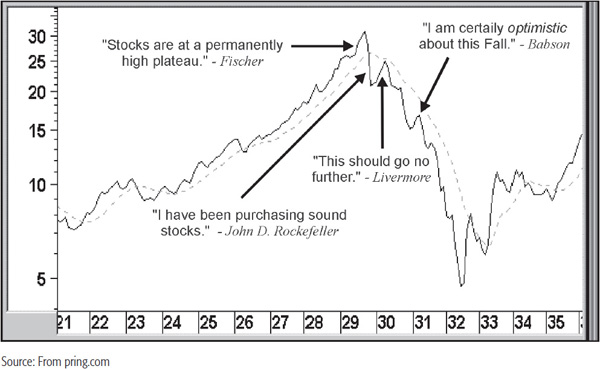

At this point, we know what the crowd thinks. It is up to us as true contrarians to come up with plausible reasons why it is likely to be wrong. In effect, we have to remove ourselves from the crowd and think in reverse. Such a process involves an understanding of the market we are watching. For example, Chart 30.3 shows the gold market at its secular peak in 1980. At that time, the price had risen from obscurity when it first started to advance in 1968 to being quoted regularly on the nightly news. It seemed to the majority at the end of 1979 that inflation and gold prices would continue to rise forever. However, a realistic contrarian would have realized that the inflation would breed its own deflation as the rising trend of short-term interest rates, driven by rising commodity prices, would cause an economic recession. In addition, the high gold price would attract more mining activity and the adoption of more efficient technologies would enable the mining of higher-cost lodes. Once again, technical analysis can come to our rescue, as Chart 30.3 shows that the 12-month ROC for gold hit a generational extreme. Silver also had a huge run-up in this period from next to nothing to over $50. The talk was of a cornering of the market by Bunker Hunt and other operatives so that it appeared that the sky was the limit. In this instance, the contrarian may have come up with the scenario that a lot of silver had already been mined and was available in the form of silverware, which could easily be melted down and sold as silver bullion. As it turned out, the price was right and the silver market was flooded just at the time when high rates of interest caused margin liquidation in the silver pits.

CHART 30.3 Gold, 1970–1999

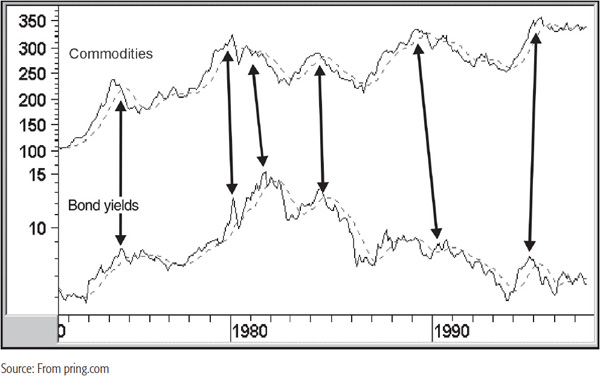

Chart 30.4 shows bond yields and commodity prices. When yields are rising and it appears this trend will never end, an alternative scenario is to use the knowledge that peaks in yields are often preceded by peaks in commodity prices, which in turn precedes a slow-down in economic activity. This is shown in the chart by the rightward sloping arrows. Thus, if it’s possible to spot a top in industrial commodity prices, the alternative scenario of weaker business activity may well come to pass.

CHART 30.4 Commodities and Bond Yields, 1970–1998

When the crowd reaches an extreme the question is not usually whether, but when and by how much. In other words, when the crowd truly reaches an extreme, it is a forgone conclusion that the trend will continue. It is not even questioned by the crowd, only the timing and amount are in doubt. Such times are often associated with analysts making extreme forecasts that in the highly charged emotional atmosphere appear credible but that would previously have been greeted with mirth or great doubt.

Sentiment Indicators Sentiment indicators, or long-term oscillators reaching an extreme, also represent one possibility for gauging that the crowd has reached an extreme.

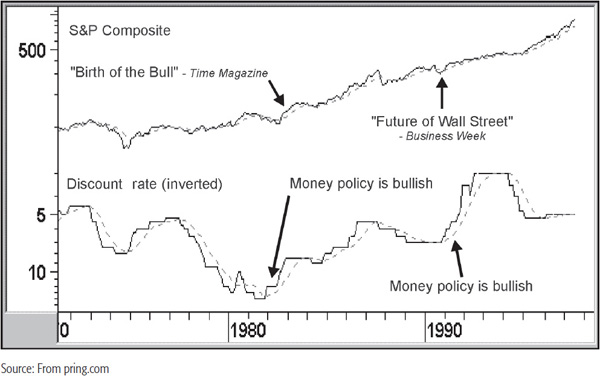

The Media Sentiment indicators are not available for every market, so another useful exercise comes from a study of the popular and financial media. Most of the time, they are silent on financial markets or individual stocks, but when significant coverage appears, that is the time to pay attention. Major peaks and troughs are often signaled by cover stories in the popular and financial press. Time, Newsweek, Businessweek, and The Economist magazine are my particular favorites. Since many of these publications are going out of print due to technological developments, we will probably have to refer to their digital editions for such information. The more of them that give space to a particular market, the stronger the signal. It’s not that the editors and writers of these magazines are idiots for publishing bear stories right at the low or bullish ones close to the absolute high. It lies more in the fact that they are journalists keeping the pulse of market conditions. As good journalists, it is their duty to give more space to articles when the emotions in and around the floors of the exchanges come close to reaching a crescendo. Generally speaking, cover stories are a fairly reliable indication of an impending turn, but they are not infallible, and often lead turning points by a week or so. As with any form of analysis, it’s important to use a good dose of common sense. For example, there is the famous “Birth of the Bull” cover story in Time magazine several weeks from the 1982 market bottom (Chart 30.5). Just applying “contrary opinion” blindly would have led to the conclusion that the bull market was over in the course of a few weeks. However, it is important to remember that it takes time for crowds to reach an extreme, as the long-term trend of rising prices adds more and more careless bulls to the fold. Also, bear markets are usually preceded by rising interest rates. In the fall of 1982 the Fed was following an easy money policy, not a tight one.

The exact opposite was true in 1990 (see Chart 30.5) when a Businessweek cover featured the troubled brokerage industry. In this instance, the prices of brokerage stocks had fallen sharply, but the Fed was engaged in an easy money policy, which is good for the equity market and certainly good for brokers, who get more underwriting fees and commissions in a bull market. In addition, the hard times they had just gone through would have resulted in substantially lowering their break-even points. Increased revenue from the bull market would then go straight to the bottom line.

CHART 30.5 S&P Composite, 1970–1999, and the Discount Rate

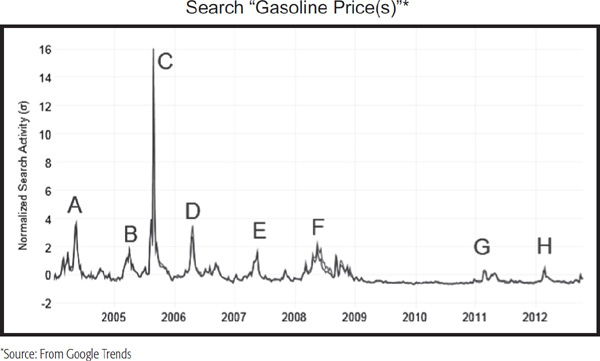

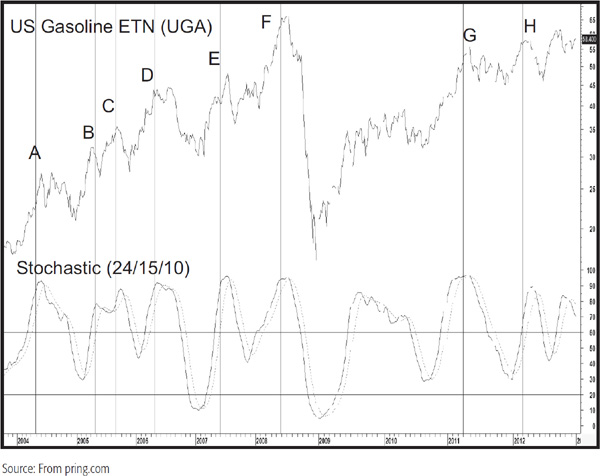

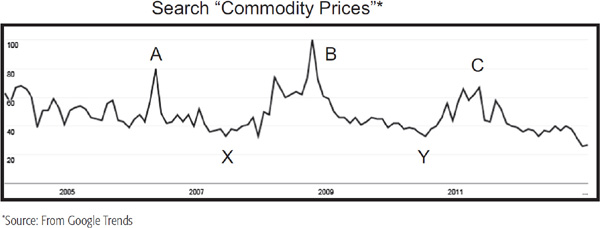

One of the problems of cover stories is that the advent of electronic media is gradually sapping the life of their print brethren. Newsweek, which I referred to earlier, no longer has a print version. One substitute is to use Google Trends, where a graph similar to that shown in Chart 30.6a is displayed for a specific search. In this case, it was “gas prices.” The various letters on the Google Search chart correspond to those on the price series in Chart 30.6b. Note that the intensity of the data does not necessarily correspond to the magnitude of the peak in gas prices and timing occasionally is early. That’s why it’s a good idea to also use an oscillator, such as the stochastic (24/15/10) featured in the lower panel of Chart 30.6b.

CHART 30.6a Google Search Gasoline Price(s)

CHART 30.6b U.S. Gasoline Prices, 2003–2012, and a Momentum Indicator

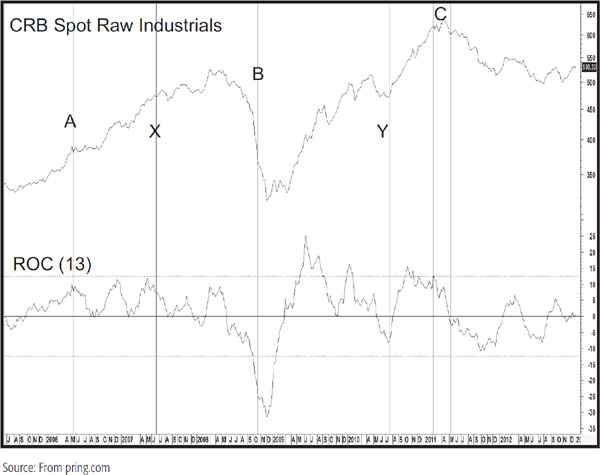

Charts 30.7a and b follow a similar path, but this time for a commodity price search. Here again, we note that extreme intensity does not translate into an extreme turning point. You can also see that points X and Y are the lowest during the search and Y certainly corresponds with a low (disinterest) in commodities. On the other hand, there seemed to be more interest in declining prices when the sharp 2008 decline was taking place. At the same time, interest was peaking momentum at B in Chart 30.7b and offered one of the lowest ROC readings in the whole 6-year period covered by the search. Combining sentiment in the form of the Google numbers with momentum paid off handsomely in this case.

CHART 30.7a Google Search Commodity Price(s)

CHART 30.7b CRB Spot Raw Industrials, 2005–2012, and a Momentum Indicator

Another way in which the media can point to major turning points is when it is possible to observe what I call a misfit story—when a heretofore “invisible” market is given the prominence it rarely, if ever, achieves.

For example, the financial media is always featuring stories on the stock or bond markets. That is normal and offering us no contrary bones. On the other hand, when we see a story in the popular press about an otherwise obscure market, then there is something to gnaw on. For example, in 1980, the sugar price peaked following a long and strong bull market. Close to the day of the high, the CBS Evening News led with a story on how traders were forecasting higher sugar prices. To my knowledge, sugar has never before or since been featured so prominently in the news. It was unusual and highly significant for the sugar market. Prominent stories in the U.S. press concerning specific “foreign” stock markets, currencies, etc., can also be valuable clues that these markets have reached an extreme. If you are long coffee, beware of media stories concerning food companies raising their price, as this unusual activity also tends to reflect major peaks.

Best-Selling Books Another area to monitor is that of best-selling nonfiction books. If a financial book appears on the list, it is usually a sign that a particular market has attracted the attention of the majority and that the good or bad news has been fully discounted. Thus, Ravi Batra’s book on the coming depression became a best-seller just after the 1987 crash, a classic sign of a bottom. The first edition of Adam Smith’s The Money Game (Vintage, 1976) reached the same list just as the mutual fund boom was ending in late 1968. Perhaps the most unlikely of all was a book on money markets by William Donahue just as short-term interest rates were making a secular peak in 1981.

Politicians A classic contrary indicator is the attitude of politicians, especially to bad news that is likely to adversely affect their election possibilities. Since politicians react to poll numbers and other trends in what we might term constituent psychology, they represent an excellent and reliable lagging indicator. They are the last to take action, and when they do, the next trend is usually underway. For instance, at the end of 1974, Gerald Ford introduced the famous W(in)I(nflation)N(ow) buttons, but consumer price inflation had, for all intents and purposes, peaked for that cycle. I remember watching the network news in the fall of 1981, right at the secular peak of interest rates. The news was full of stories of congressmen returning to Washington “determined to do something about high interest rates.” They had earfuls of complaints from their constituents and were resolute to do something about it. The problem was that the economy was already weakening and rates had peaked. When politicians promote price controls, you can be fairly certain that the specific commodity is in the process of peaking. By the same token, when oil prices are spiking and politicians start to blame the “greedy speculators,” it’s time to liquidate and probably go short oil.

Unrealistic Valuations A final pointer that the crowd has reached an extreme arises when a particular market reaches an historic level of over- or undervaluation (progressively more mispriced in John Schultz’s definition). For example, it was reported that the real estate value of the emperor’s palace in Tokyo was worth as much as all the land in California at the height of the Japanese real estate boom. In Psychology and the Stock Market (American Management Association, 1977), David Dreman noted that during the 1920s real estate boom in Florida, it was reported that there were 25,000 brokers in Miami, an equivalent of one in three of the population. This was not a valuation measure, but the statistic showed that things had clearly got out of hand. At one time in the 1990s tech boom, priceline.com, an online travel service, had a capitalization greater than the combined value of several of the airlines it represented. At its peak, the stock reached $160, but a year later it had fallen to just over $1.

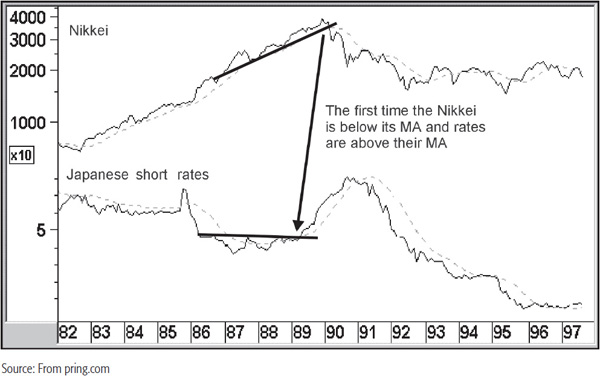

Since the crowd can and does move to an extreme well beyond normal experience, being early can be particularly harmful to one’s financial health. This is where the integration of technical analysis and the theory of contrary opinion can be quite helpful. Let’s consider a couple of examples. The Japanese bull market of the 1980s represents a classic mania where price earnings ratios and other valuation methods reached incredible extremes. The top had been called many times in the 1980s, but it never came. The crowd had clearly reached an extreme, but records continued to fall. In the end, the bubble was burst with the alternative scenario most likely to undo stock market bubbles—rising rates. Chart 30.8 shows that just after the 1990 top, both the Nikkei and Japanese short rates crossed their 12-month moving averages (MAs) for the first time in many years.

CHART 30.8 The Nikkei and Japanese Short-Term Interest Rates, 1982–1997

Both series also violated trendlines, thereby offering substantial technical evidence that the bubble had burst. Twenty-two years later, the Nikkei was still struggling at just over one-fourth of its 1990 high.

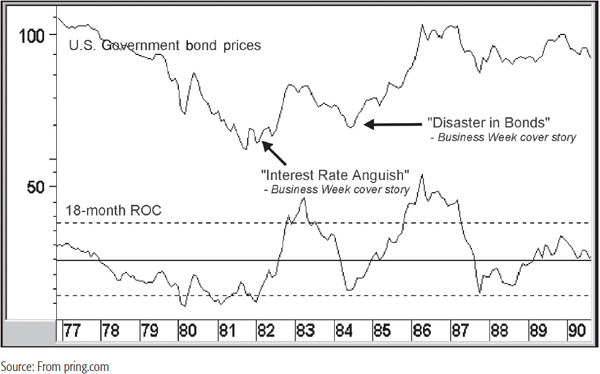

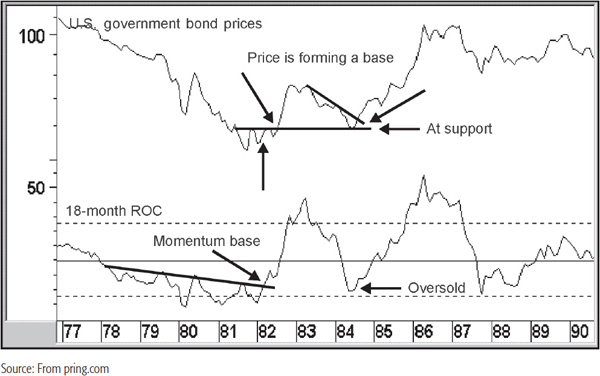

Charts 30.9 and 30.10 show two Businessweek cover stories in 1982 and 1984 concerning the bond market. The fact that the bond market should be featured so prominently after prices had fallen significantly was a sign that the crowd was at or close to an extreme. The next step was to appraise the technical position to see if there were any signs of a reversal. In the 1982 case, the 18-month ROC in Chart 30.10 had already completed and broken out of a massive 4-year base. Later on, the price broke out as well. This secondary breakout took place several months later, but it’s important to remember that we are looking at the reversal of an extremely long trend and those sorts of things take time.

CHART 30.9 U.S. Government Bond Prices, 1977–1990, and an 18-Month ROC

CHART 30.10 U.S. Government Bond Prices, 1977–1990, and an 18-Month ROC

In 1984, the “Disaster in Bonds” cover story cumulated a 2-year decline. In this instance, the ROC was close to an extreme oversold condition and the price had reached support in the form of the extended trendline marking the previous breakout. The bear market trendline break was the triggering mechanism that indicated the crowd had now moved away from the bearish extreme and was now trending in the opposite direction. In both situations, the cover stories would have indicated that the bearish arguments were now well understood and discounted and that the trend-line breaks were the signals that it was time to play the contrary “card.”

Before we close our discussion on contrary opinion, it is important to understand that the crowd can move to a smaller, less intense level of extreme. This type of sentiment is associated with a price reversal of a short-term or intermediate-term nature. An example might be a 2- to 3-week run-up in the corn price, cumulating in a lead article in the commodities section in the Wall Street Journal. Such features are not uncommon—after all, some commodity is featured every day. The idea here is that when a commodity gains such attention, it usually comes after it has experienced a significant rally or reaction. The story develops because of excitement on the floor for that particular commodity and is reflective of the crowd reaching a short-term extreme. When confirmed by a technical indicator such as a 1- or 2-day price pattern, a trendline break, or a reliable moving-average crossover, this contrary position is usually well rewarded.

Another example might come from a recently released government employment report which indicates that the economy is stronger than most traders expected. Since bond prices react unfavorably to good economic news, they could sell off sharply. Speculators now reverse sentiment from positive to a state of discouragement. Not only are bond prices declining, but rumors of a pick-up in inflation causes prices to fall even further and sentiment to become even more bearish. The consensus mood among traders is now quite black. However, the chances are that this is only a small top. The alternative scenario in this case is to look through the gloom and examine the trend of employment and other economic numbers to see if the recent report was likely to be an aberration.

1. During the unfolding of a trend, the crowd is usually right. It is at the turning points that it is wrong.

2. Three prerequisites for justifying a contrary position are the original premise becomes a dogma, the premise loses its validity, and the market becomes progressively more mispriced.

3. Three steps to forming a contrary opinion are figuring out what the crowd is thinking, coming up with alternative scenarios, and determining when the crowd reaches an extreme.

4. It is difficult to go contrary in practice because of competing forces around us.

5. When the crowd reaches an extreme, the question is not whether, but when and by how much.

6. Signs that the crowd is at an extreme include cover stories, best-selling books, reaction by politicians, extremes in sentiment indicators, and gross over- or undervaluations.

7. Since mass psychology can move well beyond the norm, technical analysis should be used as a triggering device for signaling when the crowd is backing off from a bullish or bearish extreme.

8. Contrary analysis should be used as one more indicator in the weight-of-the-evidence approach.