Broadly speaking one can say that at the beginning of the new millennium Europe’s population was thinly scattered across the continent: around the year AD 1000 there were probably no more than 30 to 35 million people in the whole of Europe (Russia and the Balkans included). From the tenth century until the beginning of the fourteenth century the population grew slowly but steadily.1 During this period the populations of France, Germany, and the British Isles probably tripled, while the population of Italy probably doubled. By the 1330s and 1340s the total population of Europe must have been at least 80 million. Then in 1348 came the Black Death, which wiped out some 25 million in a matter of about two years. Wars, famines, and above all epidemics struck again and again over the following 150 years or so, and population recovery was painfully slow. At the end of the fifteenth century the total population of Europe was still around the 80-million mark. The sixteenth century saw substantial growth, and by the beginning of the seventeenth century Europe must have totaled about 100 million people. The wars and epidemics of the seventeenth century had the effect of stabilizing the population at that level, and in 1700 Europe must still have numbered around 110 million inhabitants (see Table 1.1, p. 4).

Some of the main characteristics of the population in question have already been discussed, but it may be useful to recall at least two points. First, whatever its ups and downs, the population of preindustrial Europe remained young – in other words, the age structure consistently showed a marked prevalence of younger age groups. Secondly, notwithstanding the growth of the tenth to thirteenth centuries and of the sixteenth century, the population of Europe remained relatively small. At the high point of their demographic expansion the population of the largest countries ranged from ten to eighteen million people (see Table 1.1) and very few metropolises ever reached the 100,000 mark (see Appendix Table A.1). One could offer an extremely concise and rather sweeping explanation of this by saying that the European population remained young because of high fertility and small because of high mortality. But both points deserve further comment.

It is fashionable nowadays in scholarly circles to point to several cultural factors which helped, in one way or the other, to limit fertility in preindustrial Europe. It is commonly stated, for instance, that western Europe was characterized by a marriage pattern unique or almost unique in the world. The distinctive features of the European pattern were (a) a relatively high proportion of people never married and (b) many of those who married did so at a relatively advanced age.2 In regard to point (a) it is emphasized that in preindustrial Europe, celibacy, far from being condemned as it was in oriental societies,3 was generally praised. For priests, monks, and nuns, celibacy actually became a way of life. Until modern times in Europe intellectualism was inconceivable except in a state of celibacy. The tragedy of Abélard was rooted in this social convention. Until the end of the Middle Ages, the school of medicine at Paris did not allow married men to graduate. At Oxford and Cambridge, until the end of the nineteenth century, married men were not admitted among the fellows of the colleges.

Marriage was also avoided for economic reasons – to preserve a family estate from too many subdivisions or to avoid the cost of running a household. Fynes Moryson, a keen and witty English traveler who visited the continent in around 1700, observed:4

In Italy marryage is indeed a yoke, and that not easy one but so grevious as brethren nowhere better agreeing yet contend among themselves to be free from marryage and he that of free will or by persuasion will take a wife to continue their posterity, shall be sure to have his wife and her honour as much respected by the rest, besyde their liberall contribution to mantayne her, so as themselves may be free to take the pleasure of women at large. By which liberty they live more happily than other nations. For in those frugall commonwealths the unmarryed live at a small rate of expenses and they make small conscience of fornication, esteemed a small sinne and easily remitted by Confessors.

In more general terms, and basing his observations on the mortality bills of Breslau, Edmund Halley wrote in 1693:

The growth and increase of Mankind is not so much stinted by anything in the nature of the species as it is from the cautious difficulty most people make to adventure on the state of marriage, from the prospect of the troubles and charge of providing for a family.

Obviously all generalizations must be taken with a grain of salt. The proportion of people who never married varied greatly not only from country to country and from time to time but also according to social class, economic condition, and place of residence (see Table 5.1).

Similarly, average age at marriage must have varied greatly from time to time, from class to class, and from country to country. Moryson reported that in Germany “women are seldom marryed till they be twenty-fyve years old.”5 The tone of his remark would make one believe that in England girls married at a younger age. In the village of Colyton (England), however, over the period 1560–1646, the average age at first marriage for women was twenty-seven.6 In any case, in medieval and Renaissance Europe girls rarely married as early as girls in ancient Rome or in Asian societies, and obviously the higher the age of a woman at marriage, the lower are her probabilities of legitimate fertility over time. Table 5.2 shows the average age at first marriage for women in selected social groups and places. The figures confirm that one must be cautious in making generalizations.

Table 5.1 Percentage unmarried in selected social groups in preindustrial Europe

| English nobility | ||

| Born in the period | Percentage unmarried at 45 | |

| M | F | |

| 1330–1479 | 9 | 7 |

| 1480–1679 | 19 | 6 |

| 1680–1729 | 30 | 17 |

| Geneva bourgeoisie | ||

| Percentage unmarried among the deceased of over 50 | ||

| M | F | |

| 1550–99 | 9 | 2 |

| 1600–49 | 15 | 7 |

| 1650–99 | 15 | 26 |

| Milanese nobility | ||

| Percentage unmarried among the deceased of over 50 | ||

| M | F | |

| 1600–49 | 49 | 75 |

| 1650–99 | 56 | 49 |

| 1700–49 | 51 | 35 |

| Physicians and surgeons practising in the Grand-Duchy of Tuscany in 1630 | ||

| Percentage unmarried at 40 and over | ||

| M | ||

| 1550–90 | 20 | |

Sources: Hollingsworth, British Ducal Families, p. 364; Henry, Familles Genevoises, pp. 52–55; Zanetti, Patriziato Milanese, pp. 84–88; Cipolla, Public Health, p. 103.

Table 5.2 Average age at first marriage for women in selected social groups and places in preindustrial Europe

| Place | Period | Average age at marriage |

| Florence | 1351–1400 | 18 |

| 1401–1450 | 17 | |

| 1451–1475 | 19 | |

| England (British Peers) | 1575–99 | 21 |

| 1600–24 | 21 | |

| 1625–49 | 22 | |

| 1650–74 | 22 | |

| 1675–99 | 23 | |

| England (Village of Colyton) | 1560–1646 | 27 |

| 1647–1719 | 30 | |

| Amsterdam (Holland) | 1626–27 | 25 |

| 1676–77 | 27 | |

| Amiens (France) | 1674–78 | 25 |

| Elversele (Flanders) | 1608–49 | 25 |

| 1650–59 | 27 |

Sources : Herlihy and Klapish, Les Toscans et leurs familles, p. 205; Wrigley, Population and History, pp. 86–87; Hollingsworth, British Ducal Families, p. 364; Hart, “Historisch-demografische notitie”; Deyon, Amiens; Deprez, The Demographic Development of Flanders.

It has been argued that “in preindustrial Europe the chief means of social control over fertility was by prescribing the circumstances in which marriage was to be permitted.” On the other hand, it would be a mistake to suppose that once marriage had taken place fertility was governed solely by physiological and nutritional factors.7 Particular customs may have had some effect on fertility after marriage. It has been suggested that in parts of seventeenth-century France, a long breast-feeding period may have been adhered to in order to prolong amenorrhea among married women and thus increase the gap between births. E.A. Wrigley maintains that “there is strong statistical evidence pointing to the existence of family limitation in [the little village of] Colyton (England) during the late seventeenth century and coitus interruptus appears more likely to have been used than any other method.”8

All this is interesting but it is possible that in reaction to the previous belief in unrestrained fertility, researchers now tend to overgeneralize from some limited observations and tend to exaggerate the likely results of the facts and circumstances mentioned above. It is true that a number of Europeans did not marry, but many who did so made up for the others. Average age at marriage may have been delayed, but the number of children born to any married woman was still generally very high. Long periods of breast-feeding may have been resorted to, but high infant mortality reduced the efficacy of this method. The fact of the matter is that whenever we are able to calculate some rough figures we often find crude birth rates above 35 per thousand and almost never find rates below 30 per thousand (see Appendix Tables A.2 and A.4). Fertility could have been higher – but this fact does not mean that it was low. High fertility largely explains the youthful age structure of the population. It also accounts for the survival of the European population despite very high mortality.

Mortality was very high indeed in medieval and early modern Europe. A woman who managed to reach the end of her fertile life, let us say at age forty-five, had normally witnessed the deaths of both her parents, the majority of her brothers and sisters, more than half of their children, and often she was a widow. Death was a familiar theme. And it was a grim business. With no alleviation of pain, the bitterness of death was very real.9 To make things worse there was the cruelty of people, who had become hardened to the horror of natural death: apart from the give and take of warfare, there was the ferocity of justice, the homicidal intolerance of orthodox religion, and the lack of clemency for the weak and the captive.

As we saw in Part I, for demographic purposes it may be useful to distinguish between normal and catastrophic mortality. The distinction is arbitrary and artificial, but it has the merit of facilitating description. We have already defined normal mortality as that prevailing in normal years – i.e. years free from calamities such as wars, famines, and epidemics. In such years, the deaths of infants and adolescents represented a large proportion of overall deaths. In more technical terms, the major components of normal mortality were infant and adolescent mortalities.10

Bianca of Castilla lost four children before they reached age one and she lost three others before they reached age thirteen. Margherita of Anjou had eleven children, five of whom died before reaching the age of twenty. The death of infants and adolescents was such a common event that people scarcely took any notice of it. Of more than one hundred medical tips given by the famous physician Ugo Benzi (1376–1439) only two concern children below the age of ten. Recounting his own experience, the great Montaigne wrote “I lost two or three children as nurslings not without regret but without great grief.” In Florence, after the middle of the fifteenth century, the deaths of infants and adolescents were not even recorded in the official Books of the Deceased of the city.11 When it is possible to gather accurate and comprehensive data (see, for instance, Appendix Table A.3) one finds that in the communities of preindustrial Europe, whether large or small, for every 1,000 babies born, between 150 and 350 died before reaching one year of age, and another 100 to 200 died before reaching the age of ten.

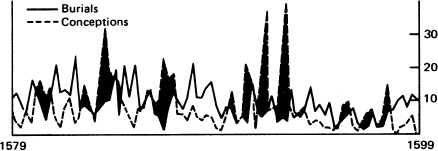

The high mortality of the young was essentially an index of the poverty of the population, of the strained conditions in which most people lived and, in the case of the well-to-do people, of the futility of medical assistance. These were conditions of selection which left only the strongest alive However, even those who had survived the hard apprenticeship of the first ten years did not enjoy an easy life for the rest of their days. Adults were as vulnerable as the young to the ravages of catastrophic mortality. The fundamental characteristic of preindustrial societies was indeed their extreme vulnerability to calamities of all sorts. The most common invocation was “a hello, fame, et peste libera nos Domine” (God deliver us from war, famine, and plague). War, famines, and epidemics relentlessly caused dramatic peaks to appear in the diagrams marking the course of mortality in the various communities (see Figure 5.1).

The brutality of warfare lives on in many literary descriptions as well as in many illuminations. Sieges were followed by massacres and by the torture of the defeated to make them reveal the whereabouts of their hidden treasures, and often religious differences gave a hideous sanction to the slaughter. People spoke of war with terror because the brutality, atrocities, and infamies of soldiering caught the imagination of all. But of the three calamities – war, famines, and epidemics – war was generally the least murderous. It was disastrous largely because of its indirect consequences, in that it provoked a greater frequency or intensity of the other two evils, famines and epidemics. Famines could easily result from the destruction and pillaging of harvests, herds, and agricultural implements. Epidemics were another common by-product of wars. The sanitary conditions of medieval and Renaissance armies were appalling. The Mayor of Padua wrote in 1631 that the soldiers were “extremely dirty and filthy individuals who, wherever they settle, give out intolerable fetor.” Early in the eighteenth century, Dr Ramazzini wrote that “in the summer there is a stench so strong from the camps that no cavern of hell could possibly be more fetid.”12 Armies were better at disseminating epidemics than at waging wars. A small army of some 8,000 soldiers that Cardinal Duc de Richelieu moved from La Rochelle to Monferrat in 1627–28 spread an epidemic of plague which killed more than one million people.13 And as Hans Zinsser once wrote, “Epidemics often determined victory or defeat before the generals knew where to place the headquarter mess.’14

Figure 5.1 Mortality and fertility in a French village (Couffé) at the end of the sixteenth century. Data are on a quarterly basis. Black areas indicate excess of burials over conceptions.

Source: Croix, “La Démographie du pays nantais”.

It is difficult for those living in the industrialized countries of the twentieth century to imagine hunger and famine. But preindustrial Europe resembled nineteenth-century India more than it did nineteenth-century Europe. The following is a description, chosen at random, of the scene that one would witness in a period of famine. The writer was a physician and the place was the northern Italian city of Bergamo in 1630:

The loathing and terror engendered by a maddened crowd of half-dead people who importune all comers in the streets, in the piazzas, in the churches, at street doors, so that life is intolerable, and in addition, the foul stench rising from them as well as the constant spectacle of the dying and the dead and particularly of people so maddened that it is impossible to escape their clutches without giving them alms, and if alms be given to one, a hundred will besiege the giver – this cannot be believed by anyone who has not experienced it.15

About the same time, a noble of Vincenza (northern Italy) wrote in a similar vein:

Give alms to two hundred people and as many again will appear; you cannot walk down the street or stop in a square or church without multitudes surrounding you to beg for charity: you see hunger written on their faces, their eyes like gemless rings, the wretchedness of their bodies with the skins shaped only by bones.

And the diarist Sanuto reported for Venice: “You cannot hear Mass without ten paupers coming to beg for alms or open your purse to buy something without the poor asking for a farthing.”16 People literally died of hunger. In the cities it was not unusual to find men dead in the streets or under the portals. In the countryside they were found at the roadside, their mouths full of grass and their teeth sunk in the earth. During the famine of 1433 and 1434 in Poland, a witness reported on “the poor gathered in Wroclaw, having their lodgings in the square and cemeteries; they perished from hunger and cold.” In Venice, in the winter of 1527, Sanuto described the scene in the following terms:

Everything is dear and every evening in the Piazza San Marco, in the streets and at Rialto stand children crying “bread, bread, I am dying of hunger and cold” – which is a tragedy. In the morning dead have been found under the portals of the Doge’s Palace.

For Bergamo in 1630, the physician M.A. Benaglio reported that “most of these poor wretches are blackened, parched, emaciated, weak and sickly ... they wander about the city and then fall dead one by one in the streets and piazzas and by the Palazzo.”17

Apart from contributing directly to the increase in mortality, famines also contributed indirectly by encouraging the outbreak of epidemics. The abbot Segni noted at the beginning of the seventeenth century that at a time of famine “most of the poor people” were attacked by illnesses “born from grasses and from poor foods,” and the good abbot explained that thus, “since the stomach cannot cook such food, nor can the liver reduce it to blood, the natural order of the body is ruined and wind, or indeed, water develops in the belly and in the legs, the skin takes on a yellow color, and people die.”18

An anonymous chronicler from Busto Arsizio (Lombardy) noted that during the famine of 1629 people were reduced to eating things from which “there followed the most atrocious and incurable diseases, which neither physicians nor surgeons were able to identify and which lasted for 6, 8, 10, or 12 months, and a great multitude of people died of them and the population of our community was reduced from eight thousand to three thousand.”19

Epidemics contributed most to the frequency and the intensity of catastrophic mortality.20 Historians always mention the Black Death but generally leave the readers with the impression that no serious epidemics hit Europe before 1348 or afterwards. The fact is that until the end of the seventeenth century not a year passed without particular cities or entire regions of Europe suffering badly from some epidemic. The most frequent epidemics were those of typhoid fever, typhus, dysentery, plague, and influenza with its lethal bronchial-pulmonary complications. Of all the infectious diseases plague was by far the most tragic and lethal, with fatality rates ranging between 60 and 75 percent in the case of bubonic plague and no less than 100 percent in the case of pneumonic plague (the reason for this high fatality rate being that the parasite that causes the plague – yersinia pestis – is a parasite of rodents and not of men).

Though wars, famines, and epidemics were not unknown in the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries, low population densities limited the devastating effects of epidemics. However, as the population grew and concentrated in the towns, the nature of the problem altered.

The population growth that took place between 1000 and 1300 did not have the intensity of demographic developments in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but even relatively low growth rates, if protracted over centuries, clearly result in explosive situations. At the beginning of the fourteenth century, several areas of Europe were overpopulated in relation to prevailing levels of production and technology. By 1339 the barren mountains of Oisans (France) achieved a population density not reached again until 1911.21 In Tuscany, the population of the territory of San Gimignano reached, in 1332, a density higher than in 1951. The population density of the territory of Volterra in the 1330s was as high as it was in 1931.22 To make things worse, people crowded into towns where water-wells were unsafe, sanitary arrangements nonexistent, and rats, fleas, and lice were overabundant. Rubbish and human and animal waste piled up on the roads and in the yards, soap was scarcely used, and personal hygiene was a little-known practice, however much physicians recommended it. The imbalance between demographic growth on the one hand and the lack of medical and public-health development on the other reached a critical point at the beginning of the fourteenth century. What happened next in Europe is a good example of how, once human action has created dangerous imbalances, equilibrium is eventually restored. It also demonstrates that famines are not the only rebalancing device in the hands of nature.

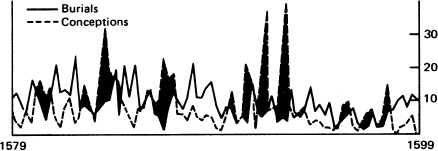

As mentioned above, between 1348 and 1351 a frightening epidemic of plague killed about 25 million people out of a total European population of about 80 million. The tragedy did not end there: the plague established itself in Europe in a more or less endemic form, and from that time onward, for about three centuries, horrible epidemics flared up from time to time on a local, regional or national scale.

The spread of the Black Death in Europe, 1347–53.

Source: McEvedy and Jones, Atlas.

In England between 1351 and 1485, plague broke out in thirty different years and between 1543 and 1593 it broke out in twenty-six years. In Venice between 1348 and 1630 plague broke out in epidemic form in twenty-one years. In Florence too plague broke out in twenty-two years between 1348 and 1500. Between 1348 and 1596 Paris was hit by plague epidemics in twenty-two years. Between 1457 and 1590 Barcelona suffered from plague epidemics in seventeen years.23

It would be hard to estimate accurately the number of casualties from plague epidemics. In his famous Natural and Political Observations upon the Bills of Mortality, first published in 1662, John Graunt remarked “that the knowledge even of the numbers which dye of the plague is not sufficiently deduced from the mere report of the searchers” and that it was necessary to make “corrections upon the perhaps ignorant and careless searchers’ reports.”24 Sir William Petty, who liked to indulge in all kinds of exercises of “political arithmetic,” wrote in 1667 that

London within ye bills hath 696 thousand people in 108 thousand houses. In pestilential yeares, which are one in twenty, there dye one sixth of ye people of ye plague and one fifth of all diseases. The people which ye next plague of London will sweep away will be probably 120 thousand, which at £7 per head is a losse of 8,400 thousand.25

More accurate estimates are available for Italian towns, and Table 5.3 shows the horrible ravages caused by the epidemics of 1630–31 and 1656–57. In general, an epidemic of plague killed, in the course of a few months, from a quarter to half of the population affected.

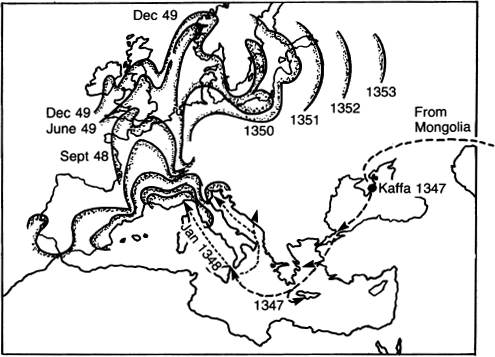

The effects of an epidemic on a given population are determined not only by the number of people killed but also by the age distribution of mortality. Clearly, if an epidemic kills mostly young people, the consequences on the subsequent development of the population in question are more severe than if it mainly kills people past their reproductive age. Nor do data on mortality tell the whole story. In the course of a famine as well as during an epidemic, not only did more people die but fewer children were born. The diagram in Figure 5.2 illustrates the typical course of mortality and fertility during a period of crisis. The “scissors” movement of fertility and mortality normally produced a hugely negative balance in the population totals.

It would be hard to overestimate the importance of these demographic crises as a long-term device in regulating preindustrial populations. Fertility was generally higher than normal mortality. Under these circumstances, population grew, although relatively slowly because the gap between fertility and mortality was slight. Sooner or later, however, a peak of catastrophic mortality would cancel out the previous demographic gains and the cycle would start all over again. In this way the frequency and severity of the peaks of catastrophic mortality determined the population trend. Turbulent political and social conditions naturally promoted the destructive action of microbes and this explains why the period of the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) and that of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) were also periods of demographic stagnation and decline.

Table 5.3 Mortality in selected Italian cities during the plague epidemics of 1630–31 and 1656–57

| Period | City | Population before the epidemic (000’s) | Number of deaths during the epidemic (000’s) | Deaths as a percentage of population (%) |

| 1630–31 | Bergamo | 25 | 10 | 40 |

| Bologna | 62 | 15 | 24 | |

| Brescia | 24 | 11 | 45 | |

| Carmagnola | 7.6 | 1.9 | 25 | |

| Como | 12 | 5 | 42 | |

| Cremona | 37 | 17 | 38 | |

| Empoli | 2.2 | 0.22 | 10 | |

| Milan | 130 | 60 | 47 | |

| Modena | 18 | 4 | 22 | |

| Monza | 7 | 4 | 57 | |

| Padua | 32 | 19 | 59 | |

| Parma | 30 | 15 | 50 | |

| Pescia | 2.8 | 1.4 | 50 | |

| Prato | 6 | 1.5 | 25 | |

| Venice | 140 | 46 | 33 | |

| Verona | 54 | 33 | 61 | |

| Vicenza | 32 | 12 | 38 | |

| 1656–57 | Genoa | 75 | 45 | 60 |

| Naples | 300 | 150 | 50 | |

| Rome | 123 | 23 | 19 |

Clearly, there was a link between the frequency of epidemics on the one hand and population density and urbanization on the other. The general impression is that the cities of preindustrial Europe had a negative demographic balance and that they survived only because of a continual inflow of people from the countryside. One of the first, if not the first scholar to make this point on the basis of statistical observation was John Graunt, who wrote in 1662:

In the said Bills of London there are far more burials than christenings. This is plain, depending only upon arithmetical computation for in forty years, from the year 1603 to the year 1644, exclusive of both years, there have been set down 363,935 burials and but 330,747 christenings within the 97, 16 and 10 out parishes; those of Westminster, Lambeth, Newington, Redriff, Stepney, Hackney and Islington not being included. From this single observation it will follow that London should have decreased in its people; the contrary whereof we see by its daily increase of buildings upon new foundations, and by the turning of great palacious houses into small tenements. It is therefore certain that London is supplied with people from out the country, whereby not only to supply the overplus differences of burials above-mentioned, but likewise to increase its inhabitants according to the said increase of housing.26

Figure 5.2 Trends in mortality, fertility, and marriage during a typical demographic crisis. The case is that of the village of Saint-Lambert-des-Levées (France).

Source: Goubert, Beauvais et le Beauvaisis.

In spite of their vitality in the economic, political, artistic, and cultural spheres, from a purely biological point of view the cities of preindustrial Europe were large graveyards.

This fact placed a limit on the process of urbanization. If more people died than were born in the cities, obviously the percentage of urban population grew, and the stronger was the brake on the growth of the total population.27 According to Father Mols, eighteenth-century Holland, for instance, was “too much urbanized” and “the natural reserve” of the country with its positive demographic balance was not enough to fill the gaps in the negative balance of the urban population.

This brief and summary outline of the history of population in preindustrial Europe must end on a mysterious note. As M. Goubert wrote of the eighteenth century, “un monde démographique semble défunt” (certain demographic patterns died out). The great peaks of mortality due to epidemics progressively subsided. Not that epidemics had become a thing of the past: there were epidemics of influenza in London in 1685 and in 1782, and an epidemic of measles in 1670. The late 1730s and 1740s saw pandemics of influenza and typhus striking most countries in Europe. However, while death rates greatly increased in such periods, momentarily exceeding birth rates, mortality no longer assumed catastrophic proportions. Even death rates of 69 and 112 per thousand, such as were recorded in Norway and the Swedish province of Värmland respectively in 1742, are still a far cry from those experienced by some regions of Europe in previous centuries.28 The most dramatic aspect of this phenomenon was the disappearance of plague. The great pandemic killer vanished as mysteriously as it had appeared three centuries earlier. There were no more plague epidemics in Italy after 1657, in England and France after the 1660s, or in Austria and Germany after the 1670s. All kinds of ingenious hypotheses have been constructed to account for this mysterious disappearance – from alleged improvements in building, to better ways of burying corpses, to the story of the invasion of the gray rat and the disappearance of the black rat. But all such hypotheses have proven untenable.

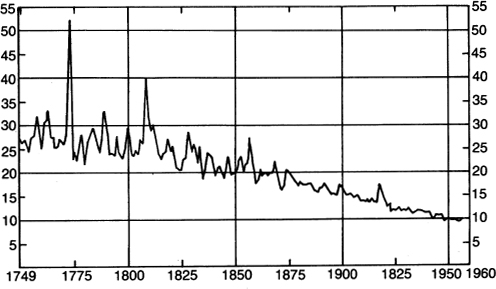

Figure 5.3 The mortality rate in Sweden, 1749–1950. This graph shows clearly how, with the advent of the contemporary age, a high level of normal mortality in Europe with frequent peaks of crisis mortality gave way to a lower level of normal mortality and the almost total disappearance of crisis peaks.

Medieval and Renaissance Europe did not go the way of Asia. European development was not halted by the suffocating pressure of population. Credit for this restraint, however, must go not so much to the rationality of the Europeans (i.e. low fertility) as to the blind action of microbes (i.e. high mortality). By the end of the seventeenth century the deadliest of the microbes had ceased its nefarious activities; and again this event was not man’s achievement, but the result of an obscure ecological revolution. Europe then embarked upon the initial stage of its so-called demographic revolution. The fact, however, that the ensuing demographic growth was not quickly arrested by the inexorable operation of Malthusian forces is attributable to the technological and economic achievements of western Europe.