5 Planning Your Argument

5.1 What a Research Argument Is and Is Not

5.2 Build Your Argument around Answers to Readers’ Questions

5.3 Turn Your Working Hypothesis into a Claim

5.4 Assemble the Elements of Your Argument

5.4.1 State and Evaluate Your Claim

5.4.2 Support Your Claim with Reasons and Evidence

5.4.3 Acknowledge and Respond to Readers’ Points of View

5.4.4 Establish the Relevance of Your Reasons

5.5 Distinguish Arguments Based on Evidence from Arguments Based on Warrants

Most of us would rather read than write. There is always another article to read, one more source to track down, just a bit more data to gather. But well before you’ve done all the research you’d like to do, there comes a point when you must start thinking about the first draft of your report. You might be ready when your storyboard starts to fill up and you’re satisfied with how it looks. You will know you’re ready when you think you can sketch a reasonable case to support your working hypothesis (see 2.3). If your storyboard is full and you still can’t pull together a case strong enough to plan a draft, you may have to rethink your hypothesis, perhaps even your question. But you can’t be certain where you stand in that process until you try to plan that first draft.

If you’re not an experienced writer, we suggest planning your first draft in two steps:

■ Sort your notes into the elements of a research argument.

■ Organize those elements into a coherent form.

In this chapter, we explain how to assemble your argument; in the next, how to organize it. As you gain experience, you’ll learn to combine those two steps into one.

5.1 What a Research Argument Is and Is Not

The word argument has bad associations these days, partly because radio and TV stage so many abrasive ones. But the argument in a research report doesn’t try to intimidate an opponent into silence or submission. In fact, there’s rarely an “opponent” at all. Like any good argument, a research argument resembles an amiable conversation in which you and your imagined readers reason together to solve a problem whose solution they don’t yet fully accept. That doesn’t mean they oppose your claims (though they might). It means only that they won’t accept them until they see good reasons based on reliable evidence and until you respond to their reasonable questions and reservations.

In face-to-face conversation, making (not having) a cooperative argument is easy. You state your reasons and evidence not as a lecturer would to a silent audience but as you would engage talkative friends sitting around a table with you: you offer a claim and some reasons to believe it; they probe for details, raise objections, or offer their points of view; you respond, perhaps with questions of your own; and they ask more questions. At its best, it’s an amiable but thoughtful back-and-forth that develops and tests the best case that you and they can make together.

In writing, that kind of cooperation is harder, because you usually write alone (unless you’re in a writing group; see 2.4), and so you must not only answer your imagined readers’ questions but ask them on their behalf—as often and as sharply as real readers will. But your aim isn’t just to think up clever rhetorical strategies that will persuade readers to accept your claim regardless of how good it is. It is to test your claim and especially its support, so that when you submit your report to your readers, you offer them the best case you can make. In a good research report, readers hear traces of that imagined conversation.

Now as we’ve said, reasoning based on evidence isn’t the only way to reach a sound conclusion, sometimes not even the best way. We often make good decisions by relying on intuition, feelings, or spiritual insight. But when we try to explain why we believe our claims are sound and why others should too, we have no way to demonstrate how we reached them, because we can’t offer intuitions or feelings as evidence for readers to evaluate. We can only say we had them and ask readers to take our claim on faith, a request that thoughtful readers rarely grant.

When you make a research argument, however, you must lay out your reasons and evidence so that your readers can consider them; then you must imagine both their questions and your answers. That sounds harder than it is.

5.2 Build Your Argument around Answers to Readers’ Questions

It is easy to imagine the kind of conversation you must have with your readers, because you have them every day:

A: I hear you had a hard time last semester. How do you think this one will go? [A poses a problem in the form of a question.]

B: Better, I hope. [B answers the question.]

A: Why so? [A asks for a reason to believe B’s answer.]

B: I’m taking courses in my major. [B offers a reason.]

A: Like what? [A asks for evidence to back up B’s reason.]

B: History of Art, Intro to Design. [B offers evidence to back up his reason.]

A: Why will taking courses in your major make a difference? [A doesn’t see the relevance of B’s reason to his claim that he will do better.]

B: When I take courses I’m interested in, I work harder. [B offers a general principle that relates his reason to his claim that he will do better.]

A: What about that math course you have to take? [A objects to B’s reason.]

B: I know I had to drop it last time I took it, but I found a good tutor. [B acknowledges A’s objection and responds to it.]

If you can see yourself as A or B, you’ll find nothing new in the argument of a research report, because you build one out of the answers to those same five questions.

■ What is your claim?

■ What reasons support it?

■ What evidence supports those reasons?

■ How do you respond to objections and alternative views?

■ What principle makes your reasons relevant to your claim?

If you ask and answer those five questions, you can’t be sure that your readers will accept your claim, but you make it more likely that they’ll take it—and you—seriously.

5.3 Turn Your Working Hypothesis into a Claim

We described the early stages of research as finding a question and imagining a tentative answer. We called that answer your working hypothesis. Now as we discuss building an argument to support that hypothesis, we change our terminology a last time. When you think you can write a report that backs up your hypothesis with good reasons and evidence, you’ll present that hypothesis as your argument’s claim. Your claim is the center of your argument, the point of your report (some teachers call it a thesis).

5.4 Assemble the Elements of Your Argument

At the core of your argument are three elements: your claim, your reasons for accepting it, and the evidence that supports those reasons. To that core you’ll add one and perhaps two more elements: one responds to questions, objections, and alternative points of view; the other answers those who do not understand how your reasons are relevant to your claim.

5.4.1 State and Evaluate Your Claim

Start a new first page of your storyboard (or outline). At the bottom, state your claim in a sentence or two. Be as specific as you can, because the words in this claim will help you plan and execute your draft. Avoid vague value words like important, interesting, significant, and the like. Compare the two following claims:

Masks play a significant role in many religious ceremonies.

In cultures from pre-Columbian America to Africa and Asia, masks allow religious celebrants to bring deities to life so that worshipers experience them directly.

Now judge the significance of your claim (So what? again). A significant claim doesn’t make a reader think I know that, but rather Really? How interesting. What makes you think so? (Review 2.1.4.) These next two claims are too trivial to justify reading, much less writing, a report to back them up:

This report discusses teaching popular legends such as the Battle of the Alamo to elementary school students. (So what if it does?)

Teaching our national history through popular legends such as the Battle of the Alamo is common in elementary education. (So what if it is?)

Of course, what your readers will count as interesting depends on what they know, and if you’re early in your research career, that’s something you can’t predict. If you’re writing one of your first reports, assume that your most important reader is you. It is enough if you alone think your answer is significant, if it makes you think, Well, I didn’t know that when I started. If, however, you think your own claim is vague or trivial, you’re not ready to assemble an argument to support it, because you have no reason to make one.

5.4.2 Support Your Claim with Reasons and Evidence

It may seem obvious that you must back up a claim with reasons and evidence, but it’s easy to confuse those two words because we often use them as if they meant the same thing:

What reasons do you base your claim on?

What evidence do you base your claim on?

But they mean different things:

■ We think up logical reasons, but we collect hard evidence; we don’t collect hard reasons and think up logical evidence. And we base reasons on evidence; we don’t base evidence on reasons.

■ A reason is abstract, and you don’t have to cite its source (if you thought of it). Evidence usually comes from outside your mind, so you must always cite its source, even if you found it through your own observation or experiment; then you must show what you did to find it.

■ Reasons need the support of evidence; evidence should need no support beyond a reference to a reliable source.

The problem is that what you think is a true fact and therefore hard evidence, your readers might not. For example, suppose a researcher offers this claim and reason:

Early Alamo stories reflected values already in the American character.claim The story almost instantly became a legend of American heroic sacrifice.reason

To support that reason, she offers this “hard” evidence:

Soon after the battle, many newspapers used the story to celebrate our heroic national character.evidence

If readers accept that statement as a fact, they may accept it as evidence. But skeptical readers, the kind you should expect (even hope for), are likely to ask How soon is “soon”? How many is “many”? Which papers? In news stories or editorials? What exactly did they say? How many papers didn’t mention it?

To be sure, readers may accept a claim based only on a reason, if that reason seems self-evidently true or is from a trusted authority:

We are all created equal,reason so no one has a natural right to govern us.claim

In fact, instructors in introductory courses often accept reasons supported only by what authoritative sources say: Wilson says X about religious masks, Yang says Y, Schmidt says Z. But in advanced work, readers expect more. They want evidence drawn not from a secondary source but from primary sources or your own observation.

Review your storyboard: Can you support each reason with what your readers will think is evidence of the right kind, quantity, and quality and is appropriate to their field? Might your readers think that what you offer as evidence needs more support? Or a better source? If so, you must find more data or acknowledge the limits of what you have.

Your claim, reasons, and evidence make up the core of your argument, but it needs at least one more element, maybe two.

5.4.3 Acknowledge and Respond to Readers’ Points of View

You may wish it weren’t so, but your best readers will be the most critical; they’ll read fairly but not accept everything you write at face value. They will think of questions, raise objections, and imagine alternatives. In conversation you can respond to questions as others ask them. But in writing you must not only answer those questions but ask them. If you don’t, you’ll seem not to know or, worse, not to care about your readers’ views.

Readers raise two kinds of questions; try to imagine and respond to both.

1. The first kind of question points to problems inside your argument, usually its evidence. Imagine a reader making any of these criticisms, then construct a miniargument in response:

■ Your evidence is from an unreliable or out-of-date source.

■ It is inaccurate.

■ It is insufficient.

■ It doesn’t fairly represent all the evidence available.

■ It is the wrong kind of evidence for our field.

■ It is irrelevant, because it does not count as evidence.

Then imagine these kinds of reservations about your reasons and how you would answer them:

■ Your reasons are inconsistent or contradictory.

■ They are too weak or too few to support your claim.

■ They are irrelevant to your claim (we discuss this matter in 5.4.4).

2. The second kind of question raises problems from outside your argument. Those who see the world differently are likely to define terms differently, reason differently, even offer evidence that you think is irrelevant. If you and your readers see the world differently, you must acknowledge and respond to these issues as well. Do not treat these differing points of view simply as objections. You will lose readers if you argue that your view is right and theirs is wrong. Instead, acknowledge the differences, then compare them so that readers can understand your argument on its own terms. They still might not agree, but you’ll show them that you understand and respect their views; they are then more likely to try to understand and respect yours.

If you’re a new researcher, you’ll find these questions hard to imagine because you might not know how your readers’ views differ from your own. Even so, try to think of some plausible questions and objections; it’s important to get into the habit of asking yourself What could cast doubt on my claim? But if you’re writing a thesis or dissertation, you must know the issues that others in your field are likely to raise. So however experienced you are, practice imagining and responding to significant objections and alternative arguments. Even if you just go through the motions, you’ll cultivate a habit of mind that your readers will respect and that may keep you from jumping to questionable conclusions.

Add those acknowledgments and responses to your storyboard where you think readers will raise them.

5.4.4 Establish the Relevance of Your Reasons

Even experienced researchers find this last element of argument hard to grasp, harder to use, and even harder to explain. It is called a warrant. You add a warrant to your argument when you think a reader might reject your claim not because a reason supporting it is factually wrong or is based on insufficient evidence, but because it’s irrelevant and so doesn’t count as a reason at all.

For example, imagine a researcher writes this claim.

The Alamo stories spread quicklyclaim because in 1836 this country wasn’t yet a confident player on the world stage.reason

Imagine that she suspects that her readers will likely object, It’s true that the Alamo stories spread quickly and that in 1836 this country wasn’t a confident player on the world stage. But I don’t see how not being confident is relevant to the story’s spreading quickly. The writer can’t respond simply by offering more evidence that this country was not a confident player on the world stage or that the stories in fact spread quickly: her reader already accepts both as true. Instead, she has to explain the relevance of that reason—why its truth supports the truth of her claim. To do that, she needs a warrant.

5.4.4.1 HOW A WARRANT WORKS IN CASUAL CONVERSATION. Suppose you make this little argument to a new friend from a faraway land:

It’s 5° below zeroreason so you should wear a hat.claim

To most of us, the reason seems obviously to support the claim and so needs no explanation of its relevance. But suppose your friend asks this odd question:

So what if it is 5° below? Why does that mean I should wear a hat?

That question challenges not the truth of the reason (it is 5° below) but its relevance to the claim (you should wear a hat). You might think it odd that anyone would ask that question, but you could answer with a general principle:

Well, when it’s cold, people should dress warmly.

That sentence is a warrant. It states a general principle based on our experience in the world: when a certain general condition exists (it’s cold), we’re justified in saying that a certain general consequence regularly follows (people should dress warmly). We think that the general warrant justifies our specific claim that our friend should wear a hat on the basis of our specific reason that it’s 5° below, because we’re reasoning according to this principle of logic: if a general condition and its consequence are true, then specific instances of it must also be true.

In more detail, it works like this (warning: what follows may sound like a lesson in Logic 101):

■ In the warrant, the general condition is it’s cold. It regularly leads us to draw a general consequence: people should dress warmly. We state that as a true and general principle, When it’s cold, people should dress warmly.

■ The specific reason, it’s 5° below, is a valid instance of the general condition it’s cold.

■ The specific claim, you should wear a hat, is a valid instance of the general consequence, people should dress warmly.

■ Since the general principle stated in the warrant is true and the reason and claim are valid instances of it, we’re “warranted” to assert as true and valid the claim wear a hat.

But now suppose six months later you visit your friend and he says this:

It’s above 80° tonight,reason so wear a long-sleeved shirt.claim

That might baffle you: How could the reason (it’s above 80°) be relevant to the claim (wear a long-sleeved shirt)? You might imagine this general principle as a warrant:

When it’s a warm night, people should dress warmly.

But that isn’t true. And if you think the warrant isn’t true, you’ll deny that the reason supports the claim, because it’s irrelevant to it.

But suppose your friend adds this:

Around here, when it’s a warm night, you should protect your arms from insect bites.

Now the argument would make sense, but only if you believe all this:

■ The warrant is true (when it’s a warm night, you should protect your arms from insect bites).

■ The reason is true (it’s above 80° tonight).

■ The reason is a valid instance of the general condition (80° is a valid instance of being warm).

■ The claim is a valid instance of the general consequence (wearing a long-sleeved shirt is a valid instance of protecting your arms from insect bites).

■ No unstated limitations or exceptions apply (a cold snap didn’t kill all insects the night before, the person can’t use insect repellent instead, and so on).

If you believe all that, then you should accept the argument that when it’s 80° at night, it’s a good idea to wear a long-sleeved shirt, at least at that time and place.

We all know countless such principles, and we learn more every day. If we didn’t, we couldn’t make our way through our daily lives. In fact, we express our folk wisdom in the form of warrants, but we call them proverbs: When the cat’s away, the mice will play. Out of sight, out of mind. Cold hands, warm heart.

5.4.4.2 HOW A WARRANT WORKS IN AN ACADEMIC ARGUMENT. Here is a more scholarly example, but it works in the same way:

Encyclopedias must not have been widely owned in early nineteenth-century America,claim because wills rarely mentioned them.reason

Assume the reason is true: there is lots of evidence that encyclopedias were in fact rarely mentioned in early nineteenth-century wills. Even so, a reader might wonder why that statement is relevant to the claim: You may be right that most such wills didn’t mention encyclopedias, but so what? I don’t see how that is relevant to your claim that few people owned one. If a writer expects that question, he must anticipate it by offering a warrant, a general principle that shows how his reason is relevant to his claim.

That warrant might be stated like this:

When a valued object wasn’t mentioned in early nineteenth-century wills, it usually wasn’t part of the estate.warrant Wills at that time rarely mentioned encyclopedias,reason so few people must have owned one.claim

We would accept the claim as sound if and only if we believe the following:

■ The warrant is true.

■ The reason is both true and a valid instance of the general condition of the warrant (encyclopedias were instances of valued objects).

■ The claim is a valid instance of the general consequence of the warrant (not owning an encyclopedia is a valid instance of something valuable not being part of an estate).

And if the researcher feared that a reader might doubt any of those conditions, she would have to make an argument supporting it.

But that’s not the end of the problem: is the warrant true always and without exception? Readers might wonder whether in some parts of the country wills mentioned only land and buildings, or whether few people made wills in the first place. If the writer thought that readers might wonder about such qualifications, she would have to make yet another argument showing that those exceptions don’t apply.

Now you can see why we so rarely settle arguments about complex issues: even when we agree on the evidence, we can still disagree over how to reason about it.

5.4.4.3 TESTING THE RELEVANCE OF A REASON TO A CLAIM. To test the relevance of a reason to a claim, construct a warrant that bridges them. First, state the reason and claim, in that order. Here’s the original reason and claim from the beginning of this section:

In 1836, this country wasn’t a confident player on the world stage,reason so the Alamo stories spread quickly.claim

Now construct a general principle that includes that reason and claim. Warrants come in all sorts of forms, but the most convenient is the When–then pattern. This warrant “covers” the reason and claim.

When a country lacks confidence in its global stature, it quickly embraces stories of heroic military events.

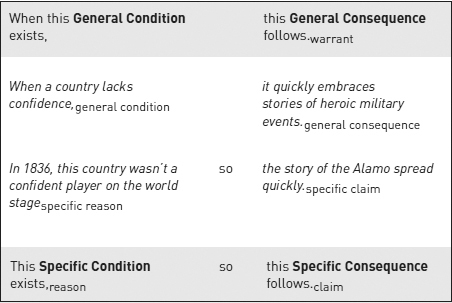

We can formally represent those relationships as in figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1. Argument structure

To accept that claim, readers must accept the following:

■ The warrant is true.

■ The specific reason is true.

■ The specific reason is a valid instance of the general condition side of the warrant.

■ The specific claim is a valid instance of the general consequence side of the warrant.

■ No limiting conditions keep the warrant from applying.

If the writer thought that readers might deny the truth of that warrant or reason, she would have to make an argument supporting it. If she thought they might think the reason or claim wasn’t a valid instance of the warrant, she’d have to make yet another argument that it was.

As you gain experience, you’ll learn to check arguments in your head, but until then you might try to sketch out warrants for your most debatable reasons. After you test a warrant, add it to your storyboard where you think readers will need it. If you need to support a warrant with an argument, outline it there.

5.4.4.4 WHY WARRANTS ARE ESPECIALLY DIFFICULT FOR RESEARCHERS NEW TO A FIELD. If you’re new in a field, you may find warrants difficult for these reasons:

■ Advanced researchers rarely spell out their principles of reasoning because they know their colleagues take them for granted. New researchers must figure them out on their own. (It’s like hearing someone say, “Wear a long-sleeved shirt because it’s above 8o° tonight.”)

■ Warrants typically have exceptions that experts also take for granted and therefore rarely state, forcing new researchers to figure them out as well.

■ Experts also know when not to state an obvious warrant or its limitations, one more thing new researchers must learn on their own. For example, if an expert wrote It’s early June, so we can expect that we’ll soon pay more for gasoline, he wouldn’t state the obvious warrant: When summer approaches, gas prices rise.

If you offer a well-known but rarely stated warrant, you’ll seem condescending or naive. But if you fail to state one that readers need, you’ll seem illogical. The trick is learning when readers need one and when they don’t. That takes time and familiarity with the conventions of your field.

So don’t be dismayed if warrants seem confusing; they’re difficult even for experienced writers. But knowing about them should encourage you to ask this crucial question: in addition to the truth of your reasons and evidence, will your readers see their relevance to your claim? If they might not, you must make an argument demonstrating it.

5.5 Distinguish Arguments Based on Evidence from Arguments Based on Warrants

Finally, it’s important to note that there are two kinds of arguments that readers judge in different ways:

■ One infers a claim from a reason and warrant. The claim in that kind of argument is believed to be certainly true.

■ The other bases a claim on reasons based on evidence. The claim in that kind of argument is considered to be probably true.

As paradoxical as it may seem, researchers put more faith in the second kind of argument, the kind based on evidence, than in the first.

This argument presents a claim based on a reason based on evidence:

Needle-exchange programs contribute to increased drug usage.claim When their participants realize that they can avoid the risk of disease from infected needles, they feel encouraged to use more drugs.reason A study of those who participated in one such program reported that 34% of the participants increased their use of drugs from 1.7 to 2.1 times a week because they said they felt protected from needle-transmitted diseases.evidence

If we consider the evidence to be both sound and sufficient (we might not), then the claim seems reasonable, though by no means certain, because someone might find new and better evidence that contradicts the evidence offered here.

This next argument makes the same claim based on the same reason, but the claim is supported not by evidence but by logic. The claim must be true if the warrant and reason are true and if the reason and claim are valid instances of the warrant:

Needle-exchange programs contribute to increased drug usage.claim When participants realize that they can avoid the risk of disease from infected needles, they feel encouraged to use more drugs.reason Whenever the consequences of risky behavior are reduced, people engage in it more often.warrant

But we have to believe that the warrant is always true in all cases everywhere, a claim that most of us would—or should—deny. Few of us drive recklessly because cars have seat belts and collapsible steering columns.

All arguments rely on warrants, but readers of a research argument are more likely to trust a claim when it’s not inferred from a principle but rather based on evidence, because no matter how plausible general principles seem, they have too many exceptions, qualifications, and limitations. Those who make claims based on what they think are unassailable principles too often miss those complications, because they are convinced that their principles must be right regardless of evidence to the contrary, and if their principles are right, so are their inferences. Such arguments are more ideological than factual. So support your claims with as much strong evidence as you can, even when you think you have the power of logic on your side. Add a warrant to nail down an inference, but base the inference on evidence as well.

5.6 Assemble an Argument

Here is a small argument that fits together all five parts:

TV aimed at children can aid their intellectual development, but that contribution has been offset by a factor that could damage their emotional development—too much violence.claim Parents agree that example is an important influence on a child’s development. That’s why parents tell their children stories about heroes. It seems plausible, then, that when children see degrading behavior, they will be affected by it as well. In a single day, children see countless examples of violence.reason Every day, the average child watches almost four hours of TV and sees about twelve acts of violence (Smith 1992).evidence Tarnov has shown that children don’t confuse cartoon violence with real life (2003).acknowledgment of alternative point of view But that may make children more vulnerable to violence in other shows. If they only distinguish between cartoons and people, they may think real actors engaged in graphic violence represent real life.response We cannot ignore the possibility that TV violence encourages the development of violent adults.claim restated

Most of those elements could be expanded to fill many paragraphs.

Arguments in different fields look different, but they all consist of answers to just these five questions:

■ What are you claiming?

■ What are your reasons?

■ What evidence supports your reasons?

■ But what about other points of view?

■ What principle makes your reasons relevant to your claim?

Your storyboard should answer those questions many times. If it doesn’t, your report will seem incomplete and unconvincing.