By the time that the US airborne divisions took part in the campaigns in the ETO in 1944, experience had already been accumulated from earlier operations in the Mediterranean Theater in 1942–44. These earlier operations had a profound effect on the doctrine and training of the US airborne divisions, so a brief survey is essential.

The first mission was conducted by the 2/503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) in French North Africa as part of Operation Torch on November 8, 1942. The operation was a bit of a mess as the mission was flown all the way from Britain to Morocco, a daunting flight under the best of circumstances, and the paratroopers were not certain whether they would land on undefended French airstrips near Oran or conduct a parachute jump against hostile forces. In the event, it was a mixture of both and the task force was unable to accomplish its mission. The force was then hastily assigned a mission to seize the Youks-les-Bains Airstrip and its large gasoline reserve on November 14, but jumped into the midst of a French battalion reinforced with armored cars. Fortunately, the French commander decided against resisting the landing, as otherwise the mission would have turned into a bloody shambles. A third mission was conducted on December 26, 1942, but was a small-scale raid involving three C-47 aircraft and 29 paratroopers assigned to blow up a key bridge in Tunisia. The teams were dropped at night, but could not find the bridge. The lessons of these early missions were obvious. Detailed planning was essential to the conduct of airborne missions; slap-dash, improvised planning was a recipe for disaster. The troop carrier units had to receive better training and joint training with airborne units; troop carrier command should not treat airborne missions as just another routine freight operation.

These lessons came at an opportune time, as plans were underway for the first large-scale airborne mission to support Operation Husky, the amphibious landings on Sicily in July 1943. Sicily was also the first joint Allied airborne operation, with the British 1st Airborne Division assigned to land near Syracuse to seize a key bridge and points south of the city, while elements of the US 82nd Airborne Division were to land behind the US Army beachhead at Gela to block the advance of Axis forces. The airborne drop on July 9, 1943, was widely dispersed due to navigation problems, landing in a swath over 50 miles, with only about 425 paratroopers of the initial 3,405 landing near Gela as planned.

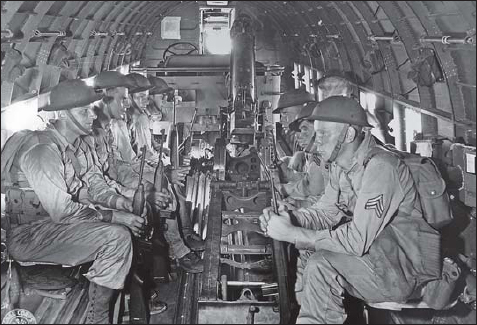

Air-landing or gliders? The German landings on Crete convinced the US Army to explore the possibility of landing troops on captured runways as one possible air-delivery technique. Here, infantry troops and an M1A1 75mm pack howitzer are air delivered during wargames in North Carolina in 1942. (MHI)

Night or day drop? The hazards of night drops are all too evident in this scene from Normandy after D-Day with a shattered Horsa littering the landing zone, and a parachute caught in the tree. Planners finally concluded that German flak was less of a threat than the difficulties of night landing, and Operation Market in September 1944 was conducted in daylight. (NARA)

In spite of the limited success of the mission, Sicily would be better remembered for the tragedy that ensued on the night of July 11 when an attempt was made to reinforce the original landing force with two battalions from the 504th PIR. The 82nd Airborne Division commander, Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgway, thought the naval commanders off Sicily had been warned adequately about the approach of the airborne train. But the mission occurred shortly after a Luftwaffe bombing raid on the fleet and as a result, during the nighttime flight to the drop zone, the warships began firing on the C-47s, shooting down 23 aircraft and seriously damaging 37 more.

The lessons from the Sicily operation continued to focus on the relatively poor training of the troop carrier pilots, particularly the difficulties experienced in night drops. Cooperation between the AAF and AGF units continued to be poor, and an after-action assessment concluded that troop carrier capabilities for glider operations were “practically zero.” Even though the Navy assured the Army that such costly fratricide would be avoided in the future by better planning, the Army became very wary of conducting nighttime missions that passed over the invasion fleet, as would be seen in the flight approach selected for the Normandy landings a year later.

The most important technical lesson was the need for improved navigation aids as well as greater attention to the use of simple routes, improved navigation training and improved nighttime formation flying. One of the immediate outcomes of the Sicily operation was the establishment of a pathfinder force, consisting of select transport squadrons with improved navigation equipment and experienced crews, and an associated paratrooper pathfinder unit that could be landed in advance of the main force to set up beacons and navigation aids for the main wave of the airborne assault.

Senior US commanders were so discouraged by the Sicily airborne operation that there was some thought of reorganizing the existing airborne divisions as light infantry divisions. The head of Army Ground Forces, Lt. Gen. Lesley McNair, commented that “after the airborne operations in Africa and Sicily, my staff and I had become convinced of the impracticality of handling large airborne units. I was prepared to recommend to the War Department that airborne divisions be abandoned in our scheme of organization and that the airborne effort be restricted to parachute units of battalion size or smaller.” However, other commanders correctly pointed out that airborne operations were still in their infancy and that if important improvements were made in coordination and training, the divisions might live up to their potential. The AAF continued to be supportive of the concept but, more importantly, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower was keen on the idea of using airborne divisions in the forthcoming invasion of France planned for the summer of 1944.

Paradoxically, while the Allies were disappointed by the airborne operations, the Germans thought they had been an important success. In spite of their dispersion, the paratroopers wreaked havoc all along the front and the Italian Army estimated it had been assaulted by a force of 20,000 to 30,000 troops. The German commander, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, acknowledged later that the paratroopers had caused unusual delays in the movement of reserves and the head of the German paratrooper force, Gen. Kurt Student, was even more effusive in his praise, stating that the Hermann Göring Panzer Division would have hurled the invasion force back into the sea were it not for the effective delay imposed by the paratroopers.

The last major airborne operation prior to D-Day was in support of the Allied landings at Salerno in September 1943. The Wehrmacht launched a mechanized counter-offensive that threatened to split the beachhead, and the Fifth Army commander, Gen. Mark Clark, requested an airborne reinforcement as quickly as possible. Within 15 hours, some 1,300 paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division were successfully dropped into the beachhead area on September 13, reinforced the following night by another regiment. Although the reinforcement mission was highly successful, many paratrooper officers wondered about the value of reinforcing a beachhead with highly trained paratroopers when they might have been used more effectively landing behind German lines. A final mission was conducted on the night of September 14–15, landing the 2/509th PIR near a mountain pass 20 miles north of Salerno with the intention of blocking it. The mission was hastily planned and the troop carriers became badly dispersed on the approach to the drop zone. The 640 paratroopers were scattered over a 100 square miles of terrain. Although they were unable to conduct their planned mission, they harassed German forces and about 510 troops managed to make their way back to Allied lines. It was another reminder of the challenge of night drops given inadequate aircrew training and the limited navigation technologies of the time.

Gliders were expected to be a cost-effective means of airborne delivery since it was presumed they would be re-usable. In reality, damage was often severe enough that they became disposable, and at a unit cost similar to a Sherman tank, not inexpensive. Here, a CG-4A is seen in the landing zone at La Motte, France, while another CG-4A prepares to land during Operation Dragoon on August 15, 1944. (MHI)

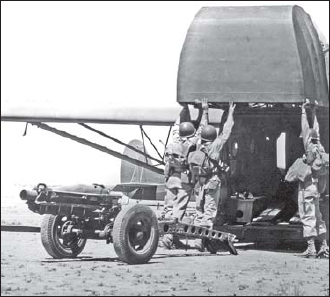

A significant advantage of gliders was their ability to carry heavier loads that were awkward for parachute delivery. Here, troops of Battery A, 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalion, 82nd Airborne Division, practice loading a 75mm M1A1 pack howitzer aboard a CG-4A glider near Oujda, Morocco, during training in July 1943. (MHI)

One of the major doctrinal questions not answered by the early combat operations was the ideal mix of paratroop versus glider units. This could not be settled as there had been delays in the production of gliders which limited training and deployment. Initially, the AGF favored a higher percentage of glider battalions over paratroop battalions, as the glider troops did not require specialized jump training and the gliders promised to be cheap and re-useable. From a tactical perspective, the early combat drops demonstrated the tendency of paratroop units to become badly scattered, leading to poor unit assembly and failed missions. Gliders promised to circumvent these problems since the unit arrived intact at the small unit (squad) level, and there was some hope that dispersion could be better controlled. In addition, gliders made it possible to land larger equipment such as jeeps, light artillery and supplies in a more convenient fashion than parachute. On the other hand, gliders took up more air time for delivery of a unit due to the spacing requirements of the gliders and the need for more relaxed formation flying to prevent mid-air collisions between tow planes and gliders. Time was a critical ingredient in airborne operations since the enemy forces were alerted once the drops began and anti-aircraft fire increased once surprise was lost. The early operations were conducted as single tows, with each C-47 towing a single CG-4A glider. It was hoped that training would improve to the point where double tows would be possible, which would help reduce the time delays of glider operations.

From the outset, the US Army realized that paratroop units would have to be manned by troops a cut above average in all respects. Jumping out of an aircraft at low altitude on a pitch-dark night, burdened with nearly 100lb of gear, and being ready to fight on reaching the ground were extreme demands not expected of ordinary infantry conscripts. Furthermore, paratroop operations often resulted in small units being widely scattered, and the troops needed a high degree of self-motivation and initiative to carry out their mission. From the outset, paratroopers were volunteers, which helped to narrow down the recruitment process. The Army offered other incentives such as an additional $50 per month in jump pay ($100 for officers). Besides the financial incentives, many adventurous young soldiers were attracted by the allure of joining an elite combat force, and esprit de corps was consciously fostered by the paratroop commanders by distinguishing the paratroopers from regular infantry troops with modified battledress, jump boots and distinctive insignia.

Most individual paratroop training was similar to the normal 13-week infantry training with the exception of jump training. Jump school at Ft. Benning was a four-week course, starting with tower jumps and culminating in five parachute jumps from aircraft, the last of which was a night jump.1 In spite of the additional jump training, the head of AGF, Gen. McNair, was very concerned about the tactical training in “trick” divisions such as these, fearing that concentration on the “trick” training would lead to slack standards in regular tactical training. Yet McNair’s concerns were largely misplaced. In combat, the excellent training and esprit de corps of the paratroopers helped to overcome the shortcomings in the tactics and divisional organization

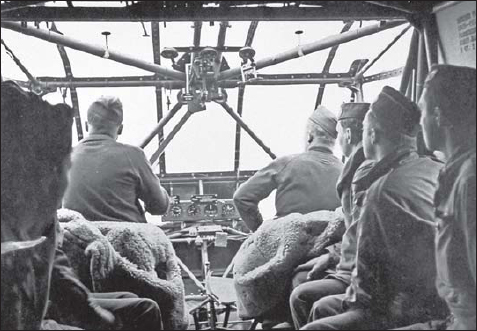

Paratroopers of Co. H, 513th PIR, 17th Airborne Division, practice on March 5, 1945, prior to Operation Varsity.This was the only unit to make combat jumps from the larger C-46 Commando aircraft, which had a pair of doors on either side instead of the C-47’s single door, necessitating additional training. (NARA)

In contrast to the paratroopers, little separated the glider infantry, or “glider riders” as they were sometimes called, from ordinary infantry. They did not receive jump training, their equipment was essentially the same as regular infantry, and they did not receive any hazardous duty pay. Indeed, the distinct differences in treatment between the glider infantry and the paratroop infantry in the airborne divisions fostered a great deal of resentment in the glider ranks. A poster appeared at one of the army air bases with gruesome photos of several glider wrecks and the slogan: “Join the Glider Troops! No Flight Pay, No Jump Pay, But—Never a Dull Moment.” The situation became serious enough that on July 1, 1944, after the D-Day operations, the Army reversed its policy and awarded extra glider pay.

Glider pilots were in a somewhat different position as they were recruited and trained by the AAF. Initial attempts to recruit pilots with civilian flight experience had to be abandoned since there was such a large demand for experienced pilots by the AAF and Navy and eventually the physical requirements for glider pilots had to be lowered to recruit enough pilots. Glider pilots went through basic training with the AAF Flying Training Command and then were assigned to Troop Carrier Command for operational training. They were classified as flying officers—not commissioned officers but not enlisted men either. Once the specialized glider training was completed, the glider pilots were then assigned to the Troop Carrier Groups and sent to one of the airbases specializing in airborne training, such as Pope Field, Laurinburg-Maxton Airbase or Lawson Field, for additional joint training. As in the case of transport pilots, they were expected to fly at least four hours per month to retain their added flight pay. One of the lingering controversies over glider pilot training was whether they should receive individual infantry training. AAF policy was that once the pilot landed the glider during a combat operation, he was to be evacuated back to the airbase as expeditiously as possible. The AAF did not want to expend highly trained pilots as infantry. However, there was some concern that once the gliders landed, the idle glider pilots would be more of a hindrance than a help in the airborne operation if they had to be defended by the glider infantry. Although there was an effort to rectify this situation prior to D-Day, in practice the glider pilots received no formal infantry training while stationed in the US. In some units stationed near airborne divisions in Britain, airborne officers provided limited training. As mentioned later, this policy changed in 1944 based on the lessons of the airborne operations.

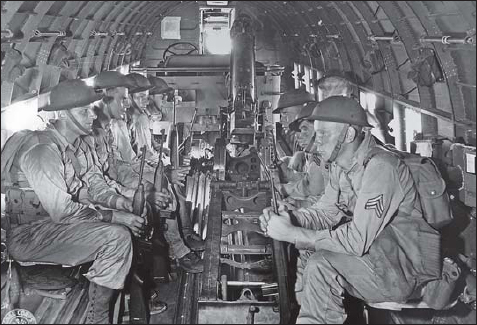

A number of exercises were conducted in 1942–43 to test new tactics. Here, a combination parachute drop and air-landing exercise is conducted at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, in 1942. (NARA)

Glider pilots and co-pilots were recruited and trained by the Army Air Force. Here, the 442nd Troop Carrier Group conducts a practice CG-4A glider mission in France in February 1945 prior to Operation Varsity. (NARA)

Troop carrier pilots were trained much the same as other AAF pilots, starting in Flying Training Command and then progressing to Troop Carrier Command for unit training. This training included both the dropping of paratroopers as well as glider tug training. Considerable emphasis was placed on night flying, since it was presumed that much of the combat flying would be conducted under the cover of darkness. There were plans underway to establish a special training area in the Great Lakes area with live anti-aircraft gun corridors to familiarize the crews with the disturbing presence of flak tracer in night flying, but this was never put into effect. In spite of the demands of the job, Troop Carrier Command did not receive priority for pilots and indeed the high demand for combat pilots led to the reduction in physical requirements for the troop carriers. An AAF jibe about pilot selection was that “many are called, few are chosen, and the rest end up in Troop Carrier.” Troop Carrier Command became a dumping ground for below-average washouts from four-engine bomber training. The commanders of Troop Carrier Command tried to reverse this attitude among senior AAF commanders as they recognized that their pilots were being tasked with some of the most demanding and difficult missions of the war—flying unarmed aircraft at altitudes of under 1,000ft, at speeds over the drop zone of only 120 miles per hour, in tight formations where it was forbidden to take evasive action even in the presence of flak. To further degrade morale, the standard C-47 transport aircraft was not fitted with self-sealing fuel tanks, which made it especially vulnerable to the type of light flak so often encountered over the drop zones. Limitations in available C-47 transport aircraft and rationing of fuel during stateside training through much of 1943 made it difficult at some bases for pilots to reach the mandatory four hours per month flying time, though this situation eased once the units forward deployed to Britain. To further complicate training, many of the flight configurations planned for the troop carriers had never been demonstrated. Double tows of CG-4A gliders did not take place on a significant scale until mid-1943, and the first aerial re-supply with door-delivered and para-pack containers was not demonstrated until December 1943. The plan was to have two crews per aircraft, but by D-Day this objective was not close to being met and there was generally only a single crew per aircraft. In many groups there was only one navigator per three aircraft but the AAF hoped to cover this deficiency by relying on tight group formations.

Large-scale joint exercises of the airborne divisions and troop carrier groups were an extremely complicated and costly undertaking. The special board headed by Maj. Gen. Joseph Swing in 1943 recommended that each division conduct at least 13 weeks of unit training and then follow this by 12 weeks of joint training with the Troop Carrier Command. The new directive for airborne training in October 1943 reduced the Swing Board recommendation from 12 weeks of combined training to eight, with the first four-week period emphasizing small-unit training such as loading, landing, assembly and entry into combat by company, with the troop carriers practicing at squadron level. The second phase would be battalion combat teams and troop carrier groups, and the final one week phase would be a major maneuver by the division and wing, moving the division in two lifts. The first large-scale joint training operation was conducted in May 1943 during the Carolina wargames by the 101st Airborne Division, moving 7,000 troops in 32 hours using three troop carrier groups. The exercise uncovered problems in the glider operations which forced more attention to be paid to air discipline and training. McNair was critical of the performance of the 101st Airborne Division in the exercise and emphasized the need for more attention to ground combat training. The largest joint exercise in the US prior to D-Day was conducted in December 1943 involving the 53rd Wing and 11th Airborne Division in the Carolinas, delivering 10,282 troops in 39 hours. The breakdown was 4,679 by parachute, 1,869 by glider and 3,734 air landed at a “captured” airport. This exercise demonstrated that problems uncovered in the May 1943 exercise had been cleared up and that double glider tow, one of the more difficult tactical problems, could now be accepted as “routine.” These large-scale exercises were of particular importance to the airborne and troop carrier staffs in ironing out the considerable problems of conducting complex airborne operations, and were an important step in the final planning for airborne operations on D-Day. Once in England, joint training tended to intensify, indeed to the point where the airborne divisions started to resist further training in the late spring due to “overtraining” and the risk of injury to trained troops. The largest and last major joint exercise prior to D-Day was Exercise Eagle starting on May 11, 1944. The results of the paratroop drops were excellent except for the less experienced new arrivals such as 315th and 442nd TCG. The glider exercises revealed lingering problems leading to “a mixture of opposition and fatalistic resignation” according to one official history.

1 For further details see Carl Smith Warrior 26: US Paratroope 1941–45 (Osprey: Oxford, 2000)