The airborne landings that spearheaded the Operation Neptune amphibious assault on Normandy were the first US airborne operations employing a full division; previous missions were no larger than regimental combat teams. The mission of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions changed considerably from the early conceptions in 1943 to the final plans in May 1944, gradually narrowing in focus to the mission of assisting the landings at Utah Beach. The February 1944 plan envisioned using the 101st Airborne Division immediately behind Utah Beach to secure the causeways off the beach that passed through areas flooded by the Germans to complicate access away from the landing areas. Bradley’s First US Army planners wanted the more experienced 82nd Airborne Division dropped further west to permit a rapid cutoff of the Cotentin Peninsula, preventing the Germans from reinforcing Cherbourg, which was the main operational objective of the Utah landings. Only days before D-Day, Allied intelligence learned of the move of the German 91st Air-landing Division into the central Cotentin Peninsula, which made the planned landing of the 82nd Airborne Division around St. Saveur-le-Vicomte too risky. Instead, its drop zone was shifted to the Merderet River area, and the 101st Airborne drop zone was shifted slightly south so that both divisions would control an easily defensible area between the beaches and the Douve and Merderet Rivers.

The first troops to land in France in preparation for Operation Neptune were OSS teams (Office of Strategic Service), usually consisting of two US soldiers, trained in the operation of signal devices, teamed with three British commandos for site security. A half dozen of these teams were flown into France around 0130hrs on June 3 to mark airborne drop zones for later pathfinder teams who would bring in more extensive marking equipment, including the Eureka beacons. Due to the weather, Operation Neptune was delayed a day to June 6, 1944. Before midnight, 19 C-47 aircraft of the Provisional Pathfinder Group set out for Normandy. On approaching the drop zones, the pathfinder aircraft encountered an unexpected cloudbank that created navigational problems. In the 101st Airborne sector, only the teams allotted to Drop Zone C parachuted close to the target. Likewise in the 82nd Airborne Division sector, only one stick of pathfinders was accurately dropped into Drop Zone O. In the case of the other four drop zones, the pathfinders were dropped so far away from their target that they did not have enough time after their landing to reach their designated drop zone. As a result, some of the pathfinder teams set off their landing beacons in areas away from the planned drop zones, while other teams were able to set up only the Eureka beacons since the presence of German troops nearby made it impossible to set up the Aldis lamps. It was an inauspicious start for the operations.

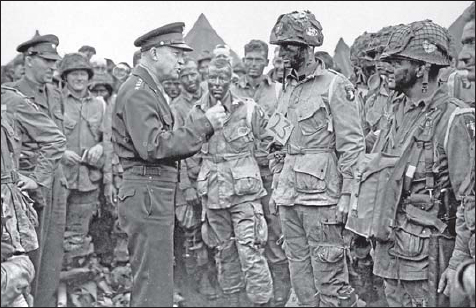

Eisenhower visited with the paratroopers of the 502nd PIR at Greenham Common airbase on the evening of June 5, 1944. The division used playing card symbols on the sides of their helmets to identify the various battalions, the white heart indicating the 502nd PIR. The white cloth band around the left shoulder is believed to be a recognition sign for the 2/502nd PIR. (MHI)

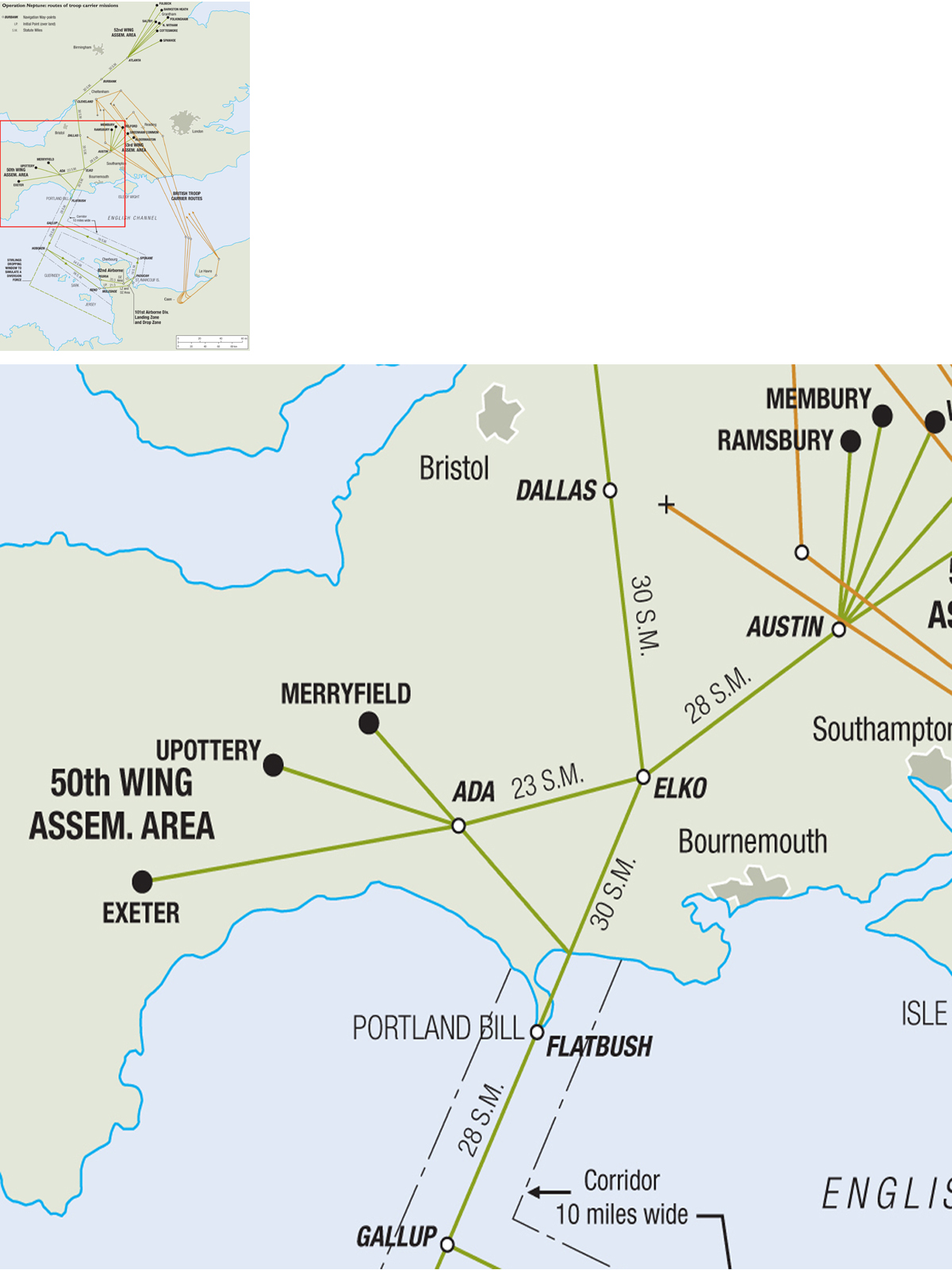

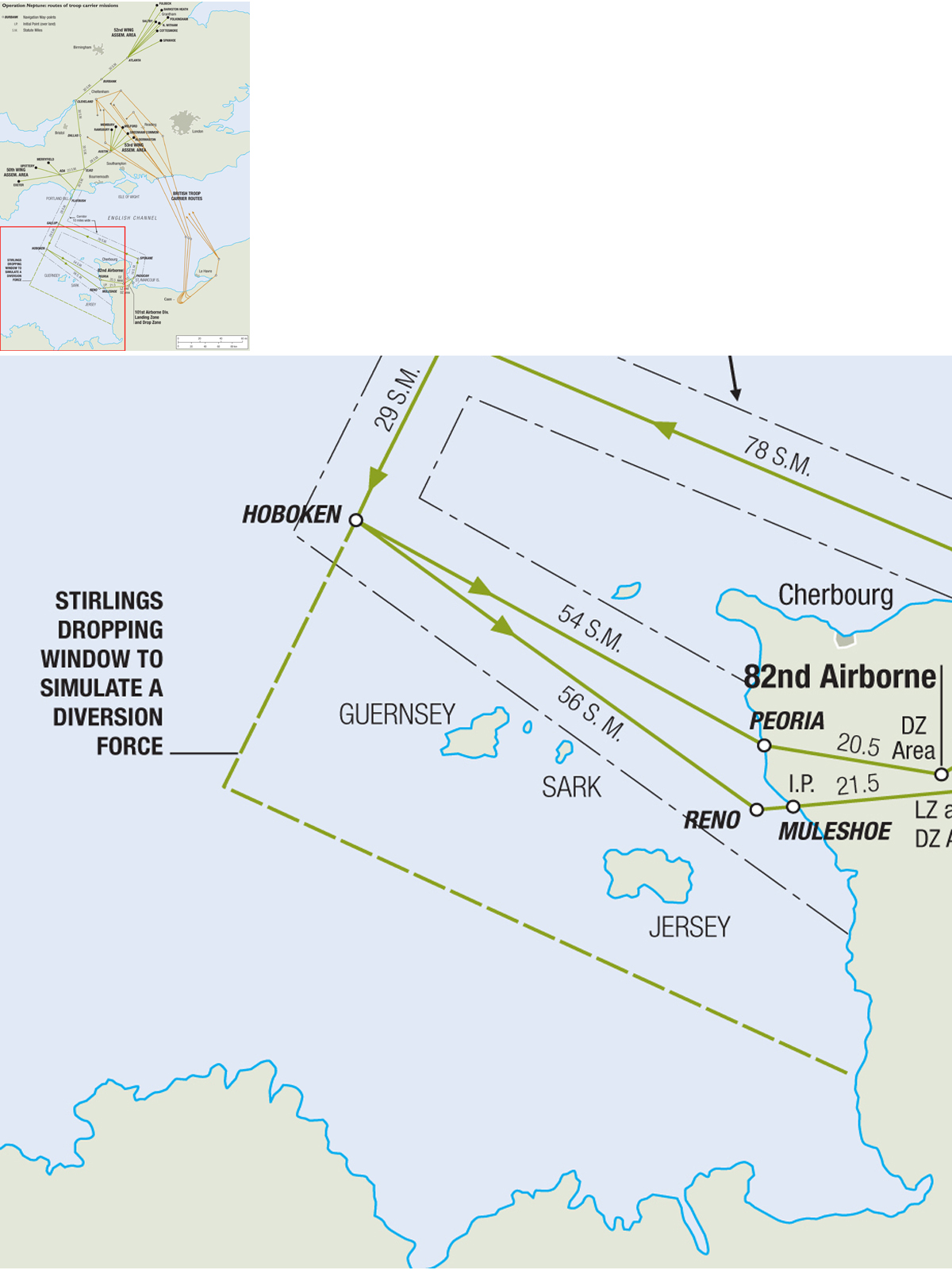

Operation Albany, the delivery of the 101st Airborne Division, was assigned to the 50th and 53rd Troop Carrier Wings, and Operation Boston, the delivery of the 82nd Airborne Division, was assigned to the 52nd Wing. The initial wave used 821 C-47 and C-53 transports. The main wave of transports began taking off from England around midnight. In the wake of the Sicily fiasco, the flight path was diverted around the naval task force westward towards the Atlantic then returning eastward, passing between the Channel Islands, and entering enemy airspace over the west Cotentin coast, heading northeastward towards the drop zone, and exiting over Utah Beach. This elongated and complicated flight path was a contributing factor to the navigation problems that plagued the D-Day airdrops.

In parallel to the actual airdrop mission, a force of RAF Stirling bombers flew a diversionary mission, dropping chaff to simulate an airborne formation and dropping dummy paratroopers and noisemakers into areas away from the actual drop zones. The weather conditions were a full moon and clearing skies. The fight proved uneventful until the coast, where the transports encountered the same dense cloudbank that had frustrated the pathfinders. The clouds created immediate dangers due to the proximity of the aircraft in formation, and C-47s began to frantically maneuver to avoid mid-air collisions. Some pilots climbed to 2,000ft to avoid the clouds, others descended below the cloudbank to 500ft, while some remained at the prescribed altitude of 700ft. This cloudbank completely disrupted the formation and ended any hopes for a concentrated paratroop drop. Anti-aircraft fire began during the final approach into the drop zones near the coast. Although they had been instructed to maintain a steady course, some pilots began jinking their aircraft to avoid steady streams of 20mm cannon fire. The airlift was becoming increasingly confused.

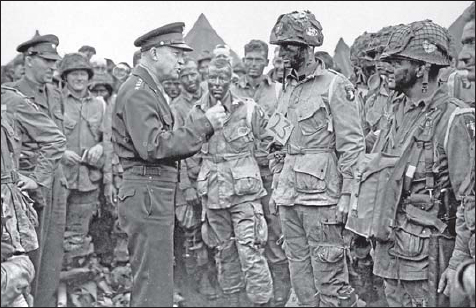

Some paratroopers of the 506th PIR, 101st Airborne Division, decided to get Mohican haircuts and daub their faces with their idea of Indian warpaint. This is demolition specialist Clarence Ware applying the finishing touches on Pvt. Charles Plaudo. The censor has obscured the “screaming eagle” divisional patch on his shoulder. (NARA)

| D-Day airlift operations, IX Troop Carrier Command | |||

| Mission | Albany | Boston | Total |

| Aircraft sorties | 433 | 378 | 821 |

| Aborted sorties | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Aircraft lost or missing | 13 | 8 | 21 |

| Aircraft damaged | 81 | 115 | 196 |

| Aircrew killed or missing | 48 | 17 | 65 |

| Aircrew wounded | 4 | 11 | 15 |

| Troops carried | 6,928 | 6,420 | 13,348 |

| Troops dropped | 6,750 | 6,350 | 13,100 |

| Howitzers carried | 12 | 2 | 14 |

| Cargo carried (tons) | 211 | 178 | 389 |

The 101st Airborne Division was the first to land around 0130hrs on June 6, 1944. Its primary objective was to seize control of the area behind Utah Beach to facilitate the exit of the 4th Infantry Division from the beach later that morning. Its secondary mission was to protect the southern flank of VII Corps by destroying two bridges on the Carentan Highway and a railroad bridge west of it, gaining control of the Barquette Lock and establishing a bridgehead over the Douve River northeast of Carentan.

The 502nd PIR and 506th PIR (minus one battalion) were assigned to the primary objective. Most of the 2/502nd PIR was dropped compactly, but inaccurately, on the far edge of Drop Zone C, three miles south of the intended Drop Zone A. In spite of the confusion, a detachment moved on the German coastal battery at St. Martin-de-Varreville and, after finding the position deserted, moved on to their next objective, the western side of the Audouville-la-Hubert Causeway (Exit 3), arriving there around 0730hrs and ambushing a German company retreating from the beach. The 1/502nd PIR landed near St. Germain-de-Varreville, with 20 of the 36 aircraft within a mile of the beacon. The 1/502nd PIR held the northern perimeter through D-Day, fighting a number of skirmishes with German troops and sending detachments to link up with the 82nd Airborne near St. Mère Eglise. The 377th Parachute Field Artillery was badly dispersed during landings and only a single howitzer was put into action on D-Day.

A fully loaded paratrooper sometimes needed help to simply move due to the enormous weight of gear and equipment he carried. This is T/4 Joseph Gorenc of the 506th PIR climbing aboard a C-47 on the evening of June 5, 1944. (NARA)

The two battalions of the 506th PIR landed in Drop Zone C. The C-47s passed over a concentration of German flak near Etienville; six aircraft were shot down and 30 damaged. In spite of the fire, some drops were concentrated with one serial of 14 aircraft dropping almost on top of Drop Zone C, and another serial of 13 bunching their sticks a mile and a half east and southeast of the drop zone. But the other serials were much further from their intended targets due to confusion over the beacons. About 140 men of the HQ and 1/506th PIR assembled in the regimental area in the first hours of the landing. The 2/506th PIR landed north of the drop zone and two disconnected groups set out to secure the Houdienville (Exit 2) and Pouppeville (Exit 1) Causeways. Delayed by frequent skirmishes with German troops, the detachments didn’t arrive near the beach until the 4th Infantry Division was already moving inland over the causeway.

Troops of the 325th Glider Infantry prepare to board Horsa gliders at an airfield in England. The US airborne units were provided with the British Horsa gliders to carry larger loads than the Waco CG-4. (NARA)

Next to land was the 3/501st PIR and the divisional HQ, which was to control the planned glider landing area near Hiesville. Gen. Taylor, not in contact with the 506th PIR, sent another detachment to the Pouppeville (Exit 1) Causeway. This was the first of the three paratrooper columns to actually reach the causeway around 0800hrs, but it took nearly four hours for the outnumbered paratroopers to overcome the German defenders in house-to-house fighting. Fighting flared up near the divisional CP in Drop Zone C due to the nearby German Artillery Regiment 191 centered on Ste. Marie-du-Mont. The paratroopers gradually eliminated the batteries, and the town was finally cleared of German troops by mid-afternoon when they were met GIs from the 4th Infantry Division advancing from the beaches.

The final groups to land were the 1/501st PIR, elements of the 2/501st PIR, and the 3/506th PIR as well as engineer and medical personnel. These forces were earmarked for Drop Zone D, the southernmost of the drop zones. The approach to the drop zone was hot, with a considerable amount of light flak, searchlights, and flares. Six C-47s were shot down and 26 damaged. These drops were among the most successful in putting the paratroopers near their intended objective, but this was not entirely a good thing as the Germans had assumed that this area could be used for airborne landings so had troops near the landing zone. In spite of casualties, a detachment from the 1/501st PIR set off for the primary objective, the La Barquette Locks, which controlled the flooding of the areas along the Douve River, and captured them by early morning. The 2/501st PIR was engaged in a sharp firefight with a German infantry battalion and spent most of the day fighting around the town of St. Côme-du-Mont. The third unit landing in Drop Zone D, the 3/506th PIR, had the roughest time. German troops were waiting in the landing area and had soaked a wooden building with fuel. They lit the building on fire, illuminating the descending paratroopers. The battalion commander and his executive officer were among those killed in the first moments. Detachments from the unit managed to fight their way free and seize the bridge at Le Port.

The 82nd Airborne Division’s assignment was to land two regiments on the western side of the Mederet River, and one regiment on the eastern side around St. Mère Église to secure the bridges over the Mederet. The landings of the 82nd Airborne were even more badly scattered than those of the 101st Airborne and, as a result, only one of its regiments was able to carry out its assignment on D-Day. The 82nd Airborne began landing about an hour after the 101st Airborne, around 0230hrs.

The 505th PIR was assigned to land on Drop Zone O to the northwest of St. Mère Église. The pathfinders had done such a thorough job marking it that many aircraft circled back over the area to drop the paratroopers more accurately and this proved to be the most accurate series of any of the jumps that night. The 3/505th PIR was assigned to take the town of St. Mère Église and the paratroopers quickly seized it. The 2/505th PIR established a defense line north of the drop zone but when the Germans staged a counterattack against St. Mère Église from the south around 0930hrs most of the battalion was moved to the southern approaches of the town except for a single platoon, which soon became engaged against another attack. The main attack against St. Mère Église was about a battalion in strength, supported by a few StuG III assault guns, but was beaten off. The 1/505th PIR landed with the headquarters including Gen. Ridgway. A group set off for the La Fière Bridge over the Mederet River but an initial attempt to rush the bridge failed due to entrenched German machine-gun teams

The two other regiments of the 82nd Airborne Division landing in Drop Zones T and N on the west side of the Mederet River, were hopelessly scattered. Pathfinders had been unable to mark the drop zones, in some cases due to the proximity of German troops. The transport aircraft were disrupted by the coastal cloudbank, and after arriving over the drop area, the pilots had searched in vain for the signals, or in some cases homed in on the wrong beacon. Much of the 507th PIR was dropped into the marshes east of Drop Zone T while the 508th was dropped south of Drop Zone N. These swamps were deep and many of the heavily laden paratroopers drowned before they could free themselves of their equipment. In addition, a great deal of important equipment and supplies landed in the water, and valuable time had to be spent trying to retrieve this equipment. About half of the 508th PIR landed within two miles of the drop zone, but the remainder landed on the other side of the Mederet River or were scattered to even more distant locations. The 507th PIR dropped in a tighter pattern than the 508th, but many aircraft overshot the drop zone, dumping the paratroopers into the swampy fringes of the Mederet River. The most noticeable terrain feature in the area of the 507th PIR drop was the railroad line from Carentan on an embankment over the marshes. Many paratroopers gathered along the embankment. A series of confused actions were fought on D-Day attempting to secure the western side of the La Fière Bridge. A group under Gen. Gavin attempted to seize the Chef-du-Pont Bridge but were rebuffed by German troops dug in along the causeway. The fighting for La Fière continued for three days and was the focus of the 82nd Airborne Division’s attention.

An element of the 88th TCS, 438th Troop Carrier Group, passes over the Normandy coast on D-Day with CG-4A gliders in tow during one of the daytime re-supply efforts. (NARA)

The next airborne missions in the early hours of D-Day were the glider reinforcement flights: Mission Detroit for the 82nd Airborne Division and Mission Chicago for the 101st Airborne Division. Mission Detroit left England at 0120hrs with 52 Waco C-4A gliders carrying 155 troops, 16 57mm anti-tank guns and 25 jeeps. The nighttime landings at 0345hrs were almost as badly scattered as the paratroopers with only six gliders on target, 15 within a kilometer, ten further west and 18 further east. Nevertheless, casualties were modest with five dead, 17 seriously injured and seven missing, although the 101st Airborne’s deputy commander was among those killed in a glider crash. The 46 CG-4A gliders of Mission Detroit landed at 0410hrs near the 82nd Airborne’s Landing Zone O, carrying 220 troops as well as 22 jeeps and 16 anti-tank guns. About 20 of the gliders landed on or near the landing zone, while seven were released early (five disappearing) and seven more landed on the west bank of the Mederet River. The rough landings in this sector led to the loss of 11 jeeps and most of the gliders, but troop losses were fewer than expected, three dead and 23 seriously injured. The nighttime glider operations were followed by additional reinforcement missions at dusk on D-Day and dawn on D+1 and their results are summarized on the chart below (page 66).

Of the 13,348 paratroops airlifted to Normandy on D-Day, only about 10 percent landed in their intended drop zone, about 25–30 percent within a mile, and 15–20 percent with one to two miles. By H-Hour (0630hrs), the 101st Airborne Division only had 1,100 troops and the 82nd only 1,500 troops near their objectives; by the end of D-Day the 101st only had 2,500 troops and the 82nd only 2,000 troops under divisional control. As a result, neither division was able to fully carry out their intended missions on D-Day, and both divisions were involved in several days of intense fighting after D-Day to secure those objectives. The causes for these problems were varied. Clearly, the navigation technology of the day and the US troop carrier tactics were inadequate. British drops relying on individual navigation and Gee were somewhat better, but neither was a practical option for the US troop carrier force in June 1944. The decision to use a roundabout route to avoid the peril of naval gunfire was unfortunate as it required more complex navigation, put the serials at greater peril of disruptive cloud cover and exposed the transport serials to more prolonged flak. Beyond the serious dispersion of the drops, the terrain contributed to the problems in assembling the units after landing. The hedgerow terrain along the Normandy coast made assembly difficult and time consuming, and the scattered paratroopers were easily delayed on encountering small German forces.

A jeep of the 506th PIR, 101st Airborne Division, pulls a handcart with supply canister near one of the landing zones off Utah Beach with Horsa gliders evident behind. By this stage, elements of the 4th Infantry Division had arrived as can be seen from the trucks and M29 carrier behind. (NARA)

In spite of problems, the paratroopers managed to accomplish an important portion of their missions largely through their courage, initiative and superior combat efficiency. But at best, the airborne missions were barely successful, and some US commanders, especially Gen. Omar Bradley, were badly disappointed with the results given the amount of effort devoted to these forces.

As was the case with the Sicily mission, the German commanders considered the Allied airborne landings in Normandy to have been a stunning success. The landings led the German 84th Corps to commit their only mobile reserve to tracking down the paratroopers, leaving them without the forces necessary to stage counterattacks against the main Omaha and Utah Beach landings. The Wehrmacht was very confused by the tactics employed, and some German staff officers were convinced that the US airborne was using a cunning new tactic of widespread dispersion to maximize the effect of light forces in undermining defensive positions. Whether they performed their specific missions on time or not, the US airborne divisions completely undermined German defenses behind Utah Beach, and the 4th Infantry Division at Utah suffered lower casualties than on any other D-Day beach. However, airborne casualties had been exceptionally high as the accompanying chart indicates, suffering almost 50 percent casualties from the time of the landing through the subsequent fighting.

The most important lesson of the Normandy airborne operation was the difficulty of night drops given the contemporary state of navigation technology. Even after the formation of the pathfinder units after Sicily, the navigation technology was marginal under the best of circumstances. All subsequent airborne operations in the ETO would be conducted in daylight on the presumption that German flak positions could be suppressed by preliminary air attack and that any remaining air defenses would be no more disruptive or costly to the landing force than the losses and inevitable dispersion caused by night landing. Technical lessons from the operation included the need for self-sealing tanks on the C-47 transport aircraft, and the need for a quick-release harness for the combat parachute. As mentioned in the organization section above, the Normandy operation reinforced the tendency to shift to a two parachute/one glider configuration as well as the need to enhance the support elements of the division.

| US airborne casualties D-Day to July 1, 1944 | |||||

| Unit | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Captured | Total |

| 82nd Abn. Div. | 457 | 1,440 | 2,571 | 12+ | 4,480 |

| 101st Abn. Div | 546 | 2,217 | 1,907 | ? | 4,670 |

| Total | 1,003 | 3,657 | 4,478 | 12 | 9,150 |

The next airborne operation in the ETO was in support of the Operation Dragoon amphibious landings on the French Riviera coast on 15 August. This operation is covered in detail in Gordon Rottman’s Battle Orders 22: US Airborne in the Mediterranean Theater 1942–45 (Osprey: Oxford, 2006), so the discussion here will be brief. The mission of Rugby Force was to serve as a buffer between the amphibious landings and any German mobile reserve, especially along the main highway heading towards St. Raphael and the shoreline. The principal airborne component of this operation was an improvised airborne division variously called the Seventh Army Provisional Airborne Division, or the 1st Provisional Airborne Task Force. This consisted of the British 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade, the 517th PIR, the 509th and 551st Parachute Infantry Battalions, and the 550th Glider Infantry Battalion. The unit was commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert Frederick, who had previously commanded the joint Canadian–American 1st Special Service Force in the Italian campaign. The air element of Rugby Force was the Provisional Troop Carrier Division, headed on a temporary basis by Brig. Gen. Paul Williams, commander of IX Troop Carrier Command during the Normandy operation. About a third of IX Troop Carrier Command was diverted to Italy for the operation and included 512 C-47s from the 50th, 51st and 53rd Troop Carrier Wings.

Glider infantry of the 1st Airborne Task Force exit their CG-4A assault glider near La Motte on the French Riviera coast on August 15, 1944, during Operation Dragoon. (NARA)

A deception operation northwest of Toulon preceded the Rugby Force airdrop. Three pathfinder teams jumped over the Le Muy area around 0330hrs on August 15 with plans to set up Eureka beacons supplemented by radio compass homing beacons. Ground fog over the target area led to a badly scattered pathfinder jump, with only one of the three teams landing in its assigned drop zone. In spite of this problem, the 396 transport aircraft had an uneventful night flight into the target area around Le Muy as the Navy had provided shipboard additional navigation beacons along the way that helped improve the accuracy of the landings. The parachute jumps began around dawn at 0430hrs and about 60 percent of the paratroopers landed in their intended drop zones or nearby, a substantial improvement over the Normandy experience. The initial glider landings, codenamed Operation Bluebird, were supposed to begin around 0800hrs with an initial force of 40 CG-4A and 35 Horsa gliders. Bluebird was delayed until 0900hrs by thick ground fog and the Horsa wave was sent back to base. The CG-4A glider landings were successfully executed and brought in jeeps, artillery and supplies. The Rugby Force proceeded to fan out and seize nearby towns and villages. The airborne force was reinforced in the afternoon by Operation Dove, a further 332 CG-4A gliders plus the returning Horsas carrying about 2,500 troops and more heavy equipment. The landings started around 1830hrs and at one point there were some 180 gliders in free flight over the landing zones. The fighting with the neighboring German garrisons was light, and by the afternoon of D+1, August 16, the paratroopers and glider infantry made contact with the 45th Division, which had landed on Red Beach in the center of the coast the morning before. Elements of the 509th Parachute Battalion were erroneously dropped near St. Tropez but captured the resort town prior to the arrival of the 3rd Infantry Division. In total, the air operation had conducted 987 sorties including 407 CG-4A gliders and had delivered 9,000 troops, 221 jeeps and 213 artillery and other heavy weapons. The 1st Provisional Airborne Task Force was subsequently assigned to cover the right flank of the Seventh Army advance, liberating the cities of Cannes and Nice. Overall, the Operation Dragoon airborne landing had gone remarkably smoothly, in no small measure due to the weak German response and the growing experience of the troop carriers and airborne units.

With the organization of the First Allied Airborne Army underway, SHAEF and the airborne staffs began considering follow-on airborne operations to employ the growing Allied airborne force. Most of those planned in July were shortlived schemes to assist in the Normandy breakout but they were made moot by the rapidity of the US Army’s advance after Operation Cobra began on July 24. Once the German Army in the west began collapsing in mid-August, the next set of schemes involved efforts to conduct a deep envelopment of retreating forces by dropping airborne forces in their path of retreat in Belgium. Once again, the pace of the ground campaign outpaced the planning and these schemes were quickly forgotten. The plans became more serious towards the end of August and British and Polish airborne units were actually deployed to airfields for some of these operations including Linnet and a portion of the troop carrier force sequestered to provide the necessary airlift.

Troops of the 82nd Division headquarters company prepare to load aboard a C-47 of the 44th TCS, 316th TCW at Cottesmore on September 17, 1944, at the start of Operation Market. (NARA)

Linnet was canceled on September 5, to be followed by a more ambitious scheme codenamed Comet, which envisioned a complex operation to seize a Rhine River bridge at Arnhem in the Netherlands on the German border northwest of the Ruhr industrial region. The British 1st Airborne Division and Polish Parachute Brigade would seize bridges over the Maas at Grave, over the Waal at Nijmegen and over the Rhine at Arnhem. US airborne engineers were to prepare a forward airfield and the British 52nd Lowland Division (Airportable) would then be landed to reinforce the airborne advance. Although Comet was canceled on September 10, Eisenhower had already come out in favor of using the First Allied Airborne Army to assist Montgomery’s 21st Army Group in a rapid race to the Rhine, giving it priority over other options such as Patton’s advance through Lorraine towards Frankfurt. Comet was modified to incorporate the US XVIII Airborne Corps, with the airborne mission codenamed Operation Market, and the ground assault by the British XXX Corps, supported by VIII and XII Corps, designated Garden. The new assignments were to land the 101st Airborne Division near Eindhoven to clear a path for the advance of the armored divisions of the British XXX Corps; land the 82nd Airborne Division around Nijmegen to seize the Waal River bridges there; and land the British 1st Airborne Division near Arnhem to seize a Rhine bridge, with plans to drop the Polish Parachute Brigade as reinforcements once airlift became available. The plans expected the XXX Corps to reach the Arnhem Bridge by D+3 or +4. In view of the problems experienced in Normandy with night landings, Operation Market was scheduled to take place on the afternoon of September 17, with an elaborate tactical air plan to suppress German flak positions.

| Canceled First Airborne Army operations, summer 1944 | ||||

| Codename | Planned date | Drop zone | Airborne unit | Mission |

| Wildoats | June 14 | Evrecy | British 1st Airborne Division | Clear the way for British 7th Armoured Division attack |

| Hands Up | mid-July | Quiberon Bay | Undetermined | Seize ports |

| Beneficiary | mid-July | St. Malo | Undetermined | Seize port |

| Swordhilt | end of July | Brest | Undetermined | Seize port |

| Transfigure | August 17 | Orléans gap | US 101st, UK 1st Abn. Div., Polish Bde. | Trap German Seventh Army |

| Boxer | end of August | Boulogne | Undetermined | Seize port, harass retreating German forces |

| Linnet | September 2–3 | Tournai | US 82nd, 101st, UK 1st Abn. Div.; Polish Bde. | Cut off retreating Germans |

| Linnet II | September 4–6 | Liège | US 82nd, 101st, UK 1st Abn. Div.; Polish Bde. | Seize Meuse River crossing |

| Comet | September 8 | Arnhem | Undetermined | Seize Rhine bridges from Arnhem to Wesel |

| Infatuate | September | Walcheren Island | Undetermined | Assist Canadian Army to clear access to Antwerp |

| Naples I | September | East of Aachen | XVIII Airborne Corps | Assist First Army break through the Siegfried Line |

| Naples II | September | Cologne area | XVIII Airborne Corps | Seize Rhine bridge in Cologne area |

| Milan I | September | Trier area | XVIII Airborne Corps | Assist Third Army to penetrate Siegfried line |

| Milan II | September | Koblenz area | XVIII Airborne Corps | Assist in Rhine crossing in Neuweid-Koblenz area |

| Choker I | September | Saarbrucken | XVIII Airborne Corps | Assist Seventh Army to break through Siegfried Line |

| Choker II | September | Mannheim | XVIII Airborne Corps | Assist a crossing of the Rhine between Mainz and Mannheim |

| Talisman | September | Berlin | Undetermined | In the event of a sudden German collapse, seize Berlin airfields and naval base at Kiel |

The US airborne landings were intended to pave the way for the armored columns of the British XXX Corps. Here, two paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division talk to the crew of a British Stuart light tank of the Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry, 8th Armoured Brigade, which provided armored support in late September and early October. (MHI)

The US airborne commanders were disturbed by the initial British plans which they felt were too hastily conceived. Gen. Taylor was deeply uneasy with the idea that the 101st Airborne would capture and control a pathway some 30 miles long from the forward Allied lines through Eindhoven and beyond towards Nijmegen. In the event, Taylor spoke to the commander of the British XXX Corps, Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey, about this and he agreed that there was no urgent need for the paratroopers from Eindhoven south, which made the objectives difficult but possible. Gen. Gavin was less concerned with the overall plan than in the particulars, and one significant change was to place the landing of the 504th PIR closer to the Maas River bridge near Grave, including a company immediately on the bridge’s western approach. In contrast to the Normandy mission, Operation Market’s tactical planning was more than a little slapdash and impromptu, with very little training of the airborne units possible. British assessments of likely German reactions were too optimistic and US commanders were very surprised to learn that the British 1st Airborne Division planned to land eight miles from the Arnhem Bridge instead of nearby this key objective.

Glider infantry of the 327th GIR, 101st Airborne Division, move off Landing Zone W near Son on September 18, 1944, (D+1) while a jeep from the regimental service company passes by. (NARA)

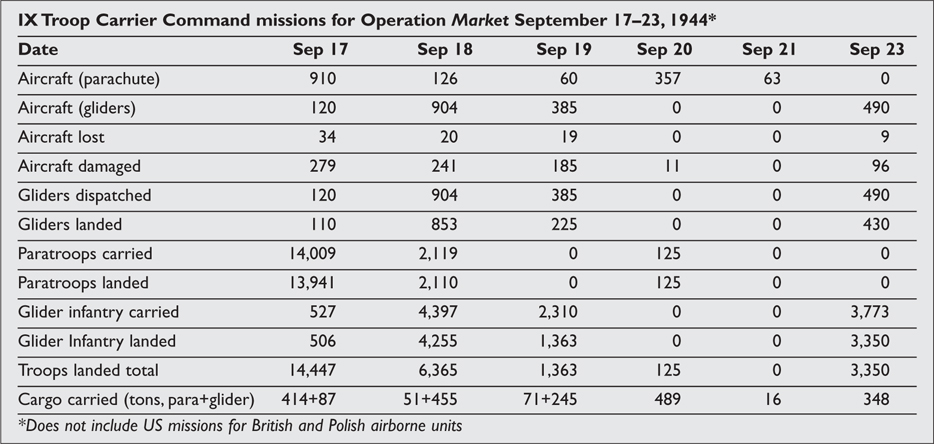

The airlift operation was complicated by the need to fly from bases in England since bases in France were being used by tactical aviation. This was somewhat ameliorated by Brereton’s arrangement to borrow 250 B-24 bombers to conduct a major re-supply effort on D+2, but it weakened the strength of the initial landings during the first few days of good weather. This complex battle has been described in detail many times, and the focus here will be the US XVIII Airborne Corps efforts in the Eindhoven–Nijmegen area.

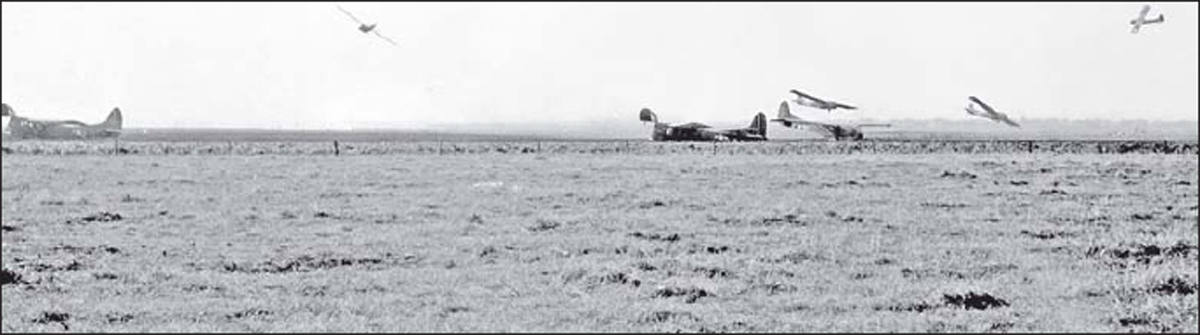

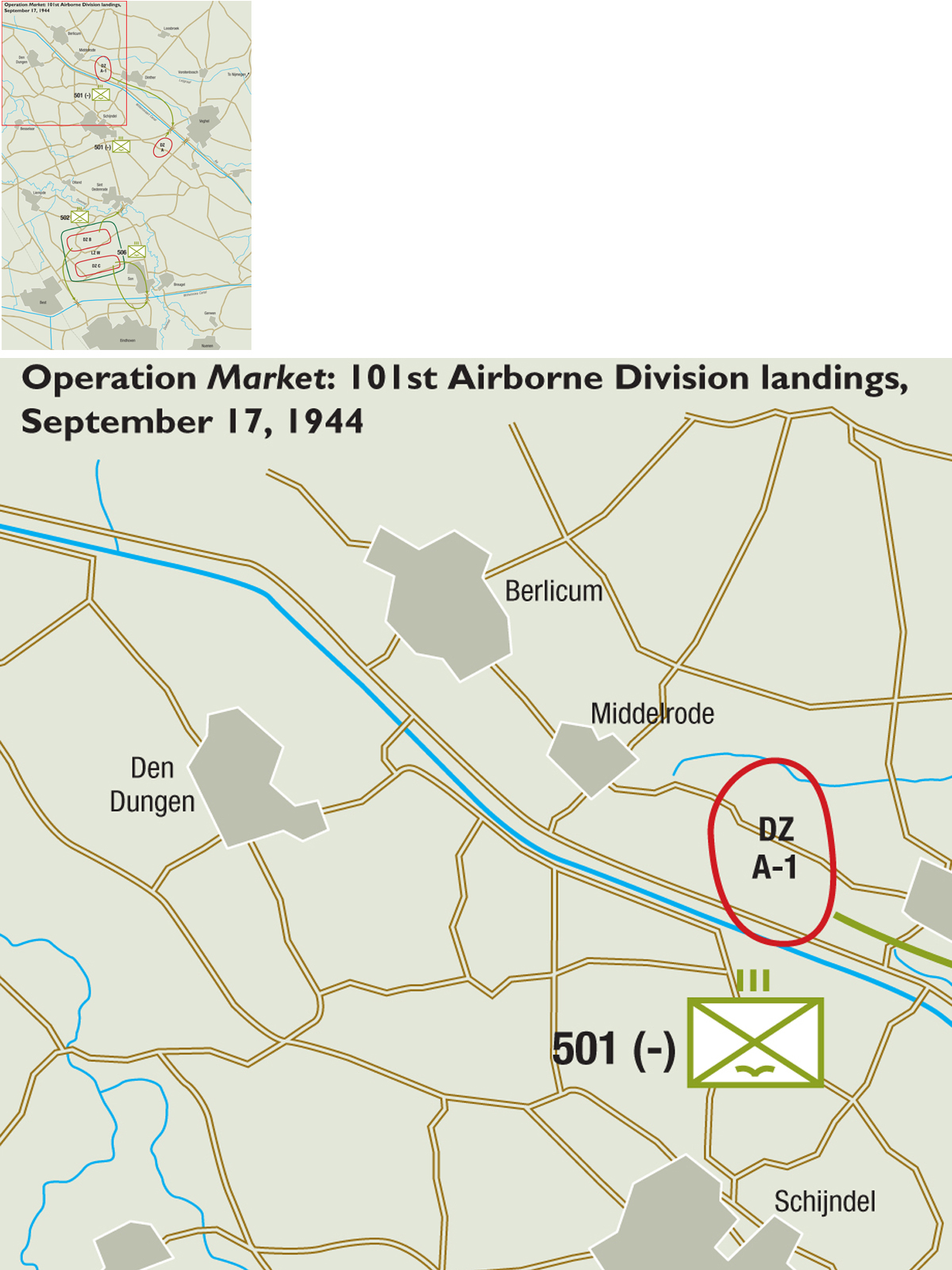

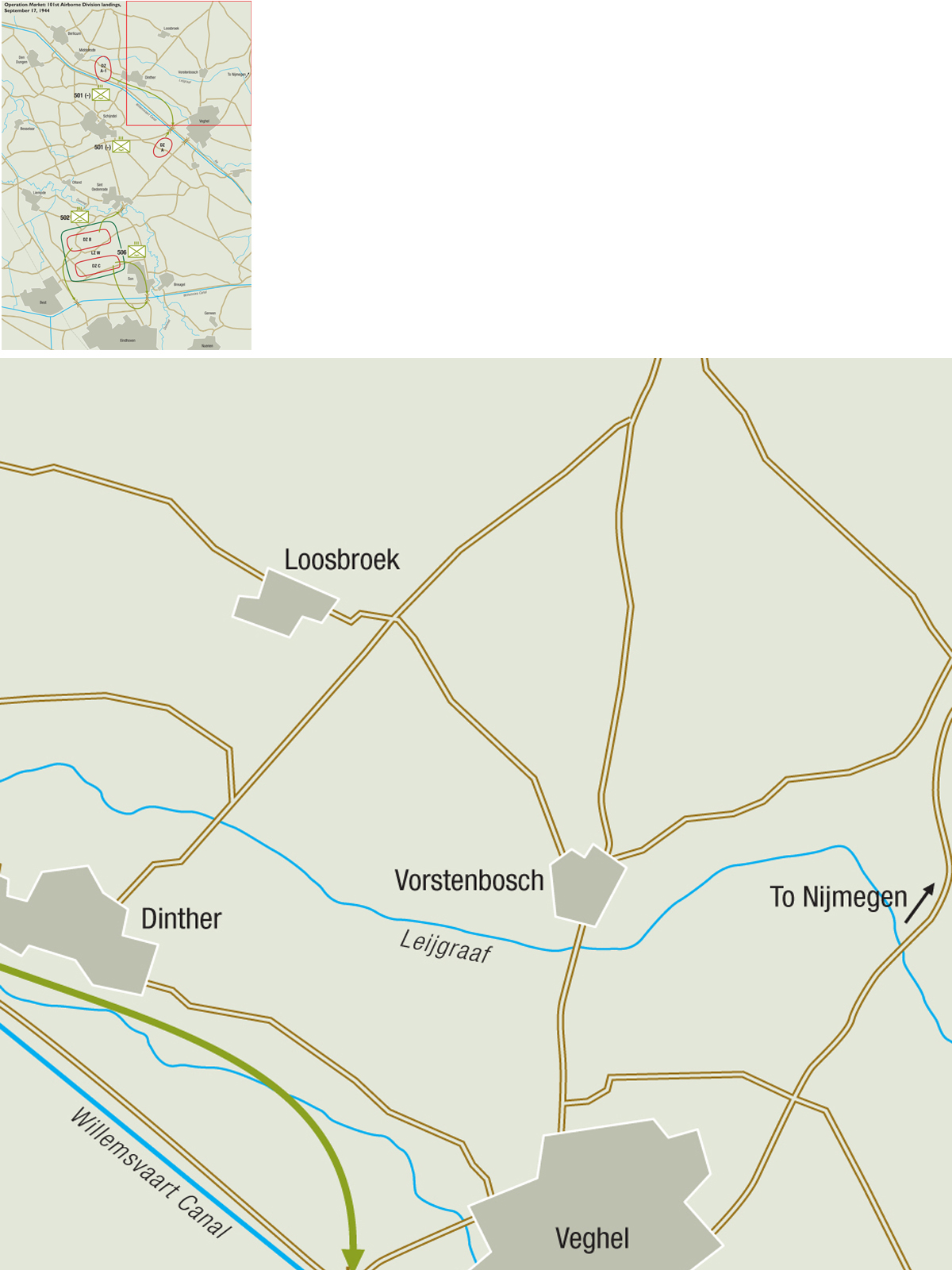

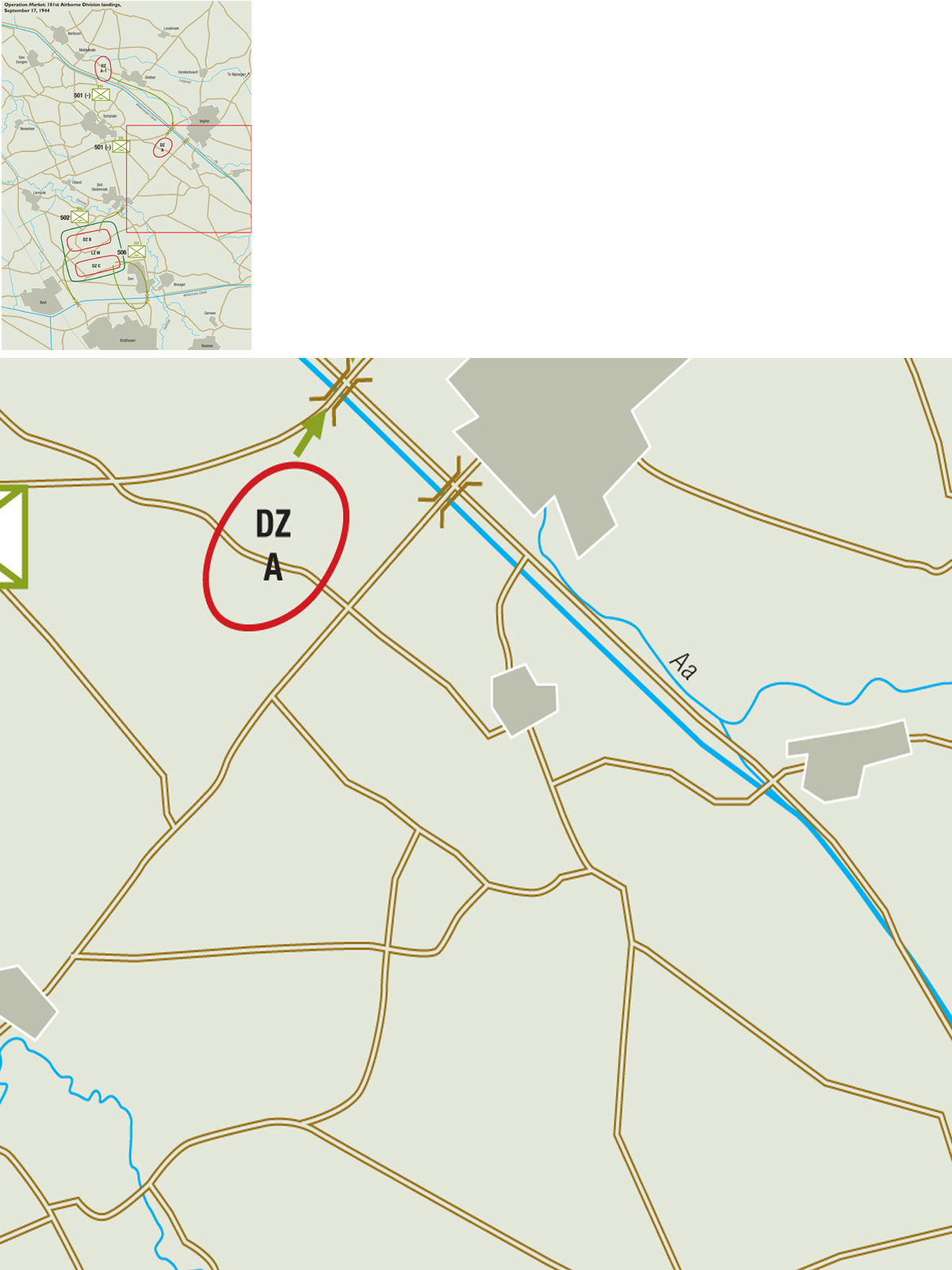

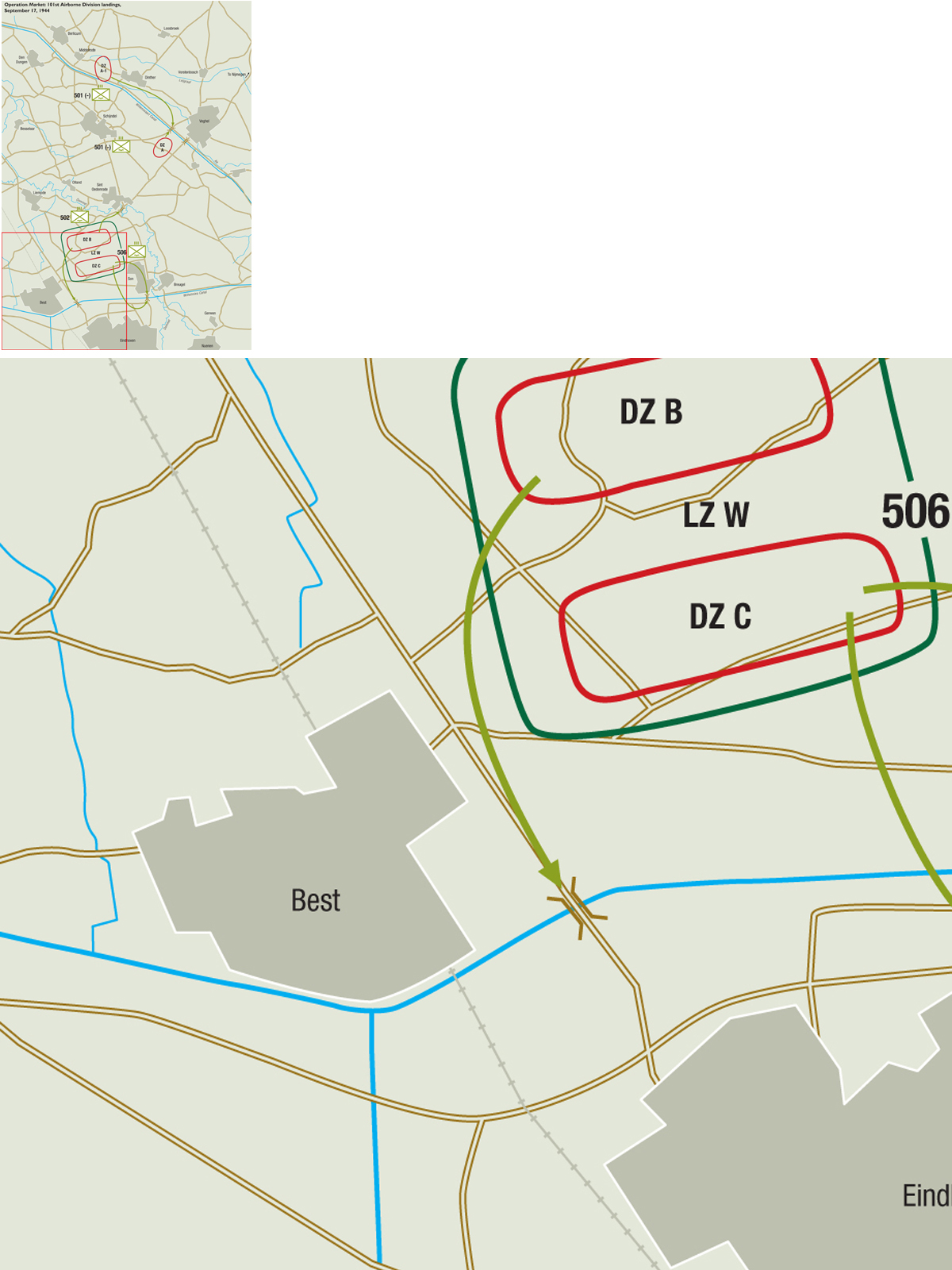

The initial 101st Airborne Division force was carried to the Netherlands in 428 transports and 70 gliders on the afternoon of September 17, 1944. The main landing area was located north of Eindhoven and west of Son, consisting of Drop Zone B for the 502nd PIR, Drop Zone C for the 506th PIR and Landing Zone W for the gliders. The 501st PIR landed further north in two separate drop zones, A and A-1 to the southwest and northwest of Veghel on the Aa River. The 501st PIR landing was not entirely accurate, but the main objectives of the four bridges over the Aa River and the Willemsvaart Canal were quickly seized. The 502nd PIR seized the bridge over the Dommel River at St. Oedenrode and over the Wilhelmina Canal near Best, but the Best Canal bridge was recaptured by a German counterattack before dark. The 506th PIR moved on Son where two of the bridges had already been blown the week before, and the Germans detonated the remaining bridge before the paratroopers could capture it. Nevertheless, the 506th PIR was able to establish control of the town on both sides of the Wilhelmina Canal by nightfall, waiting for the next day to link up with XXX Corps near Eindhoven.

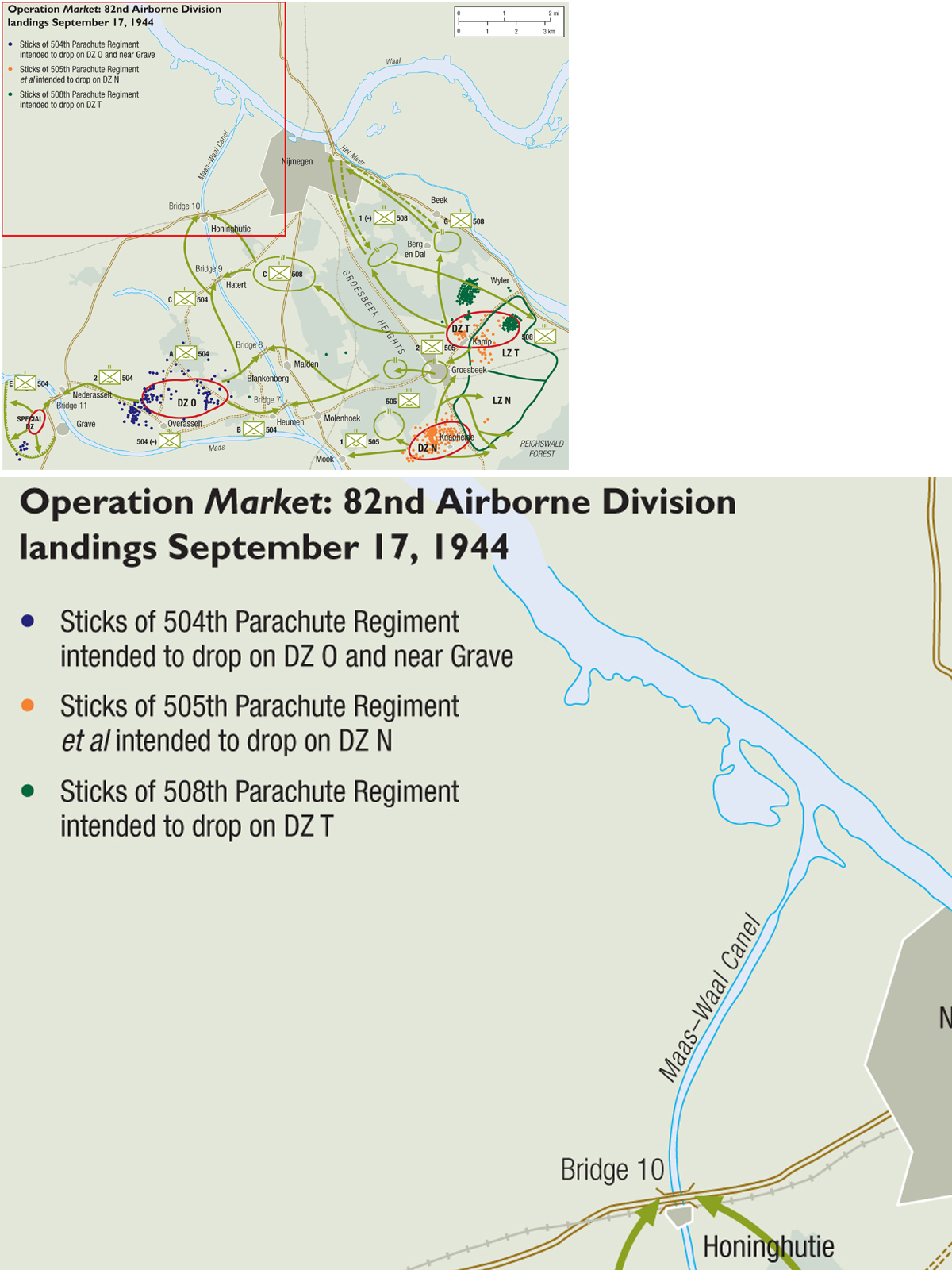

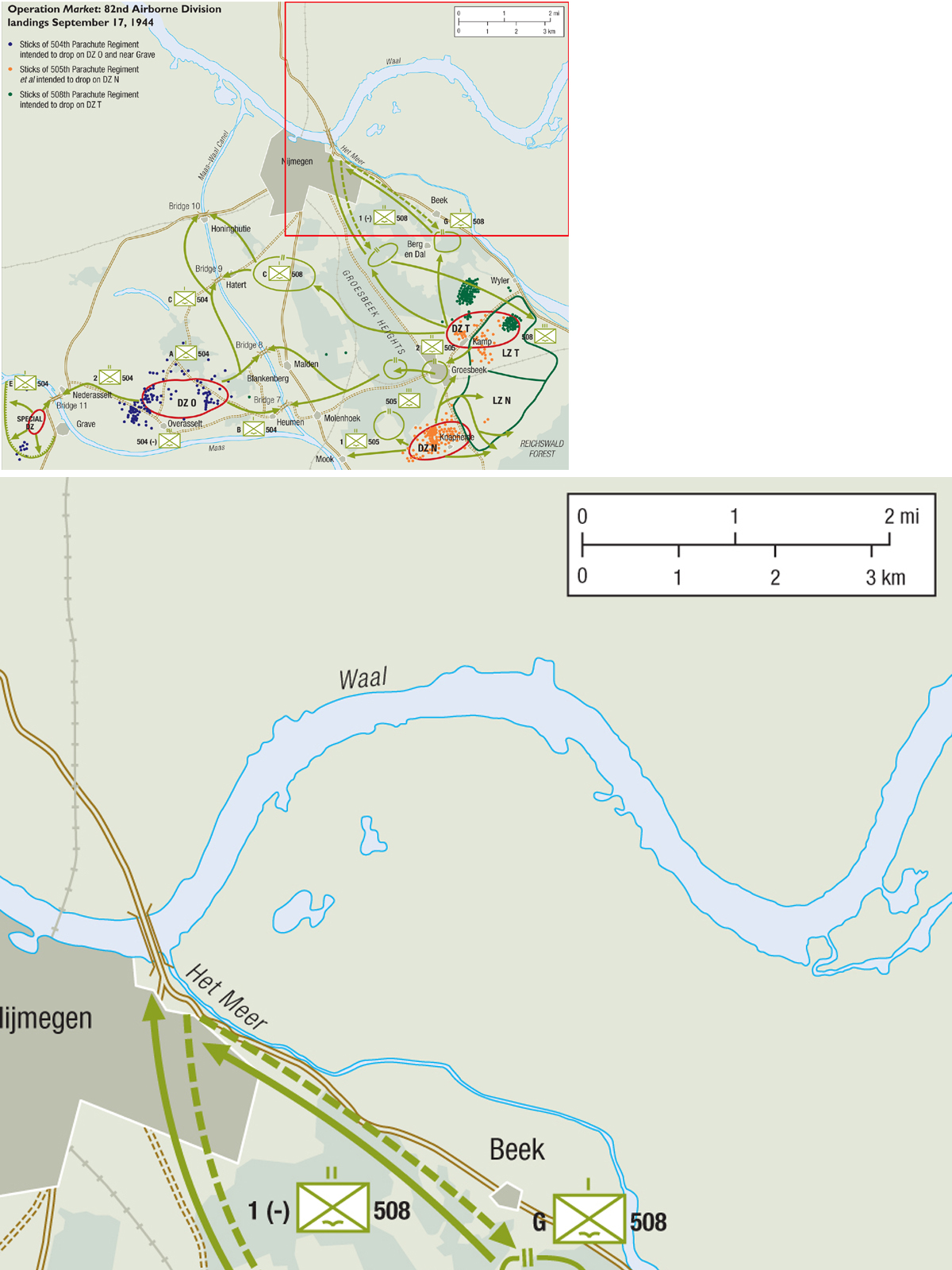

The 82nd Airborne Division was carried into action by 400 transport aircraft and 50 gliders including 7,277 paratroopers and 209 glider infantry. The 504th PIR landed in two drop zones on either side of Grave and its Maas River bridge, taking the Grave Bridge (Bridge 11) before dusk. The regiment was also tasked with capturing the western side of four other bridges along the Maas–Waal Canal in conjunction with other units of the division from the eastern side. The southernmost bridge (Bridge 7) was captured, the ones north of Malden (Bridge 8) and Hatert (Bridge 9) were blown by the Germans, and the damaged bridge at Honinghutie was seized the following day (Bridge 10). The 505th PIR landed further east around Groesbeek in two drop zones, established a defensive perimeter towards the Reichswald to the southeast and linked up with the 504th PIR along the Maas–Waal Canal. The Germans had already demolished the railroad bridge on the northwest side of Mook. The 508th PIR landed northeast of Groesbeek and its principal mission was to seize and control the high ground west of Berg en Dal including Hill 95.6, which dominated the flat Dutch landscape in the area. This was accomplished and two companies reached to within 400 yards of the Nijmegen road bridge. This bridge was not an immediate objective of the first day’s plans and the companies stopped after meeting fierce resistance.

A dramatic view from Landing Zone W around 1430hrs on D+1 (September 18, 1944), as CG-4A assault gliders land near Son. (NARA)

Overall, the first day’s operation had been a considerable success compared to the Normandy drops. Fighter-bombers had managed to suppress German flak positions and losses totaled 35 transport aircraft and 13 gliders, less than six percent of the troop carrier contingent. The pathfinders had generally been successful, and while not all the landings were on the drop zones, they were close enough that the divisions did not have undue trouble assembling their forces. The Wehrmacht did not anticipate the airborne attack so resistance on the first day was light. The fighting would intensify dramatically over the next few days as the Germans attempted to stamp out the landings, attacking the Allied forces on all sides of the salient.

The 101st Airborne Division pressed south towards Eindhoven on the morning of September 18, while the British Guards Armoured Division pressed north. The paratroopers captured the city by early afternoon and linked up with the British tanks in the evening around 1900hrs. After quickly bridging the Wilhelmina Canal in the dark, the Guards Armored Division crossed around dawn on September 19 and raced up to the 82nd Airborne Division sector by 0820hrs. Combined British and American attacks to seize the vital Nijmegen Bridge were repulsed through September 19 due to the arrival of elements of the 10th SS-Panzer Division from the Arnhem area. But in a bold move, the 82nd Airborne outflanked the defenses on the afternoon of September 20 by using boats to cross a mile downstream from the bridge. Last-minute German attempts to detonate the bridge failed and British tanks were streaming over the bridge that night, heading for Arnhem.

Nevertheless, the delays caused by the initial defense at Eindhoven, the need to build a bridge at Son, and the fighting for the bridge at Nijmegen had slowed the advance by XXX Corps and put it behind schedule. German resistance against the 1st Airborne Division in Arnhem was far fiercer than anticipated due to the unexpected presence of two Waffen-SS panzer divisions refitting in the area. The poor weather after the first day, combined with radio problems, made it difficult and sometimes impossible to conduct supply drops to the encircled British paratroopers, and most of the supplies ended up falling into German-controlled areas. By the time that XXX Corps reached the approaches to Arnhem on September 21, the situation in the city was dire. The surviving airborne troops holding the western side of the bridge were forced to retreat that day to the main concentration of the 1st Airborne Division but were unable to do so and were killed or fell prisoner. With resistance intensifying all around the Allied salient by September 22, the British Second Army gave permission to withdraw forces if necessary. The positions of the 1st Airborne Division were untenable and permission to withdraw was given on September 25, with the action taking place on the night of September 25–26. The Allied positions in the Netherlands were so tenuous, and the German counterattacks so vigorous, that initial plans to withdraw the two US airborne divisions at the conclusion of Operation Market were continually frustrated. Both divisions were reinforced by landing administrative units and additional vehicles in Normandy by sea and then sending them by road into the combat zone. In addition, both divisions had an assortment of British units attached to them. The Canadian II Corps did not arrive in the Netherlands until November, and so the 82nd Airborne Division remained in the line until November 11–13, and the 101st Airborne Division until November 25–27.

| US airborne casualties, Operation Market: September 17–October 16, 1944 | ||||

| Unit | Killed | Wounded | Missing | Total |

| 82nd Airborne Division | 336 | 1,912 | 661 | 2,909 |

| 101st Airborne Division | 573 | 1,987 | 378 | 2,938 |

| Total | 909 | 3,899 | 1,039 | 5,847 |

The failure of Operation Market-Garden can be traced to numerous factors, in many cases too complex to examine in this short survey. The operation was inherently risky, presuming that the crisis in the Wehrmacht would last through September and beyond. The basic strategic premise was proven to be incorrect and, instead of collapsing, the German forces in Holland resisted much more fiercely than expected. The violent German reaction in Arnhem was unanticipated due to the failure to recognize that the 2nd SS-Panzer Corps was refitting in the area. Besides these fundamental planning misjudgments, the airborne operation had important lessons. The decision to use a daylight drop proved fully justified as it contributed significantly to the accuracy of the drops and the speed in assembling the forces on the ground. The most serious shortcoming of the troop carrier operation was the time it took to deliver the forces. Due to the range from England, the lack of forward airfields in France and the shortage of aircrews, the transports could only fly one sortie per day. The delivery of the three divisions was extended over a period of three days as a result, which seriously compromised the operation. For example, the need to guard the landing areas and drop zones for later waves of troops forced the ground commanders to divert as much as a third of their forces to this secondary task, weakening their attacks. Poor weather further contributed to the stretch-out of the later drops intended for D+2 and the Polish 1st Airborne Brigade was not delivered until D+4, while the 325th GIR was not delivered until D+6. Had the Poles been present at Arnhem sooner, it might have affected the fighting for the bridge. Had the 325th GIR been present near Nijmegen sooner, it might have permitted a more rapid seizure of the bridge, facilitating the advance of the British XXX Corps armored columns. Yet even if the bridge at Arnhem been seized and held, it is by no means clear that the strategic objective of the mission would have been attained since the Rhine crossing was merely the means to inject Montgomery’s 21st Army Group into the Ruhr industrial area to outflank the Siegfried Line. With the Wehrmacht rapidly recovering from the summer disaster and the Allies’ logistical links overstretched, a deep penetration into Germany before the onset of winter was doubtful, whether the Arnhem Bridge was captured or not.

Troops of the 506th PIR scramble to free the crew trapped in a CG-4A glider of the 84th TCS on Landing Zone W, which was involved in a mid-air collision with another glider after one of the pilots was wounded in the face by flak. (NARA)

The B-24 Liberator bomber was used on several occasions to supplement transport aircraft for dropping supplies during airborne operations as is seen here in September 1944 during Operation Market.This required the bottom ball-turret to be removed to create a suitable opening for the para-pack drop. (Patton Museum)

From the airborne perspective, Brereton already understood the need for forward airfields to facilitate airborne operations on the Continent and attempted to establish a troop carrier center around Reims prior to Operation Market. This could not be accomplished until the autumn due to the commitment of so much of the troop carrier force to Operation Dragoon and Market in quick succession, as well as the continual diversion of the force for forward airlift of fuel and supplies. In addition to forward basing, Brereton also accelerated training in glider double-tow, which would enable the limited transport force to substantially increase the number of gliders delivered. Although this had been demonstrated in 1943, the poor performance of this tactic in Burma in early 1944 had discouraged its use in Europe through most of 1944.

A recurring controversy raised again by Operation Market was the use of US glider pilots after landing. The British practice was to form them into their own company and use them as reinforcing infantry if necessary. The US practice of evacuating them as soon as possible proved unworkable and the presence of so many unarmed personnel was at times more of a hindrance than a help. In practice, the glider pilots often volunteered as infantry, but there was no organized system and the pilots received inadequate infantry training. This led to a decision to provide some training and organization for future operations.

Allied airborne operations in the wake of Operation Market-Garden were inhibited by Montgomery’s insistence that the two US divisions remain in the line for an extended period to assist the British Second Army in the Netherlands until other infantry became available. Since both the British 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions were refitting after suffering heavy losses in Normandy and at Arnhem, and the US 13th and 17th Airborne Divisions were still stateside, there were no airborne forces to conduct airborne missions. By late autumn, the Allied armies were conducting very limited offensive operations after having outrun their logistical capabilities. Bradley wanted to revive Operation Choker II, an operation between Mainz and Mannheim to support the US Seventh Army, but the resources were not available.

During the crisis in the Ardennes in December 1944, the two airborne divisions were the US Army’s only available reserve. Here, the 2/504th PIR advances near Cheneux, Belgium, on December 22, 1944. To the right is an airborne 6-pdr, a lightweight British counterpart to the 57mm anti-tank gun used by the airborne divisions. (NARA)

Attention briefly shifted to potential operations in the late winter when major offensives over the Rhine were anticipated. In the event, the unanticipated German offensive in the Ardennes starting on December 17, 1944, forced the commitment of the 82nd, 101st and newly arrived 17th Airborne Divisions since they were the only reserve available to Bradley’s 12th Army Group. Although they had not completed their refitting, the 82nd and 101st were rapidly shipped by truck from Reims to Belgium, in many cases without adequate winter clothing or sufficient ammunition. The 101st Airborne Division was assigned to defend the little-known town of Bastogne at a key road junction on the approaches to the Meuse River, one of the key German objectives.2 The defense of Bastogne became the 101st Airborne Division’s most legendary combat action. One of the few airborne elements to the battle was the use of the troop carriers to lift supplies to the besieged town, including a number of small glider lifts to bring in supplies and medics. The 82nd Airborne Division, along with XVIII Airborne Corps headquarters, was assigned the St. Vith sector further to the northeast. By the time it had arrived, the advance of the Sixth Panzer Army had already been stymied but there was still hard fighting ahead through the remainder of December and early January 1945. The 17th Airborne Division saw its combat debut in the Ardennes, being sent into the line in January 1945 during the efforts to reduce the bulge. The desperate shortage of infantry forced the commitment of other paratroop units including a number of separate battalions and regiments. The 517th PIR, later part of the 13th Airborne Division, was deployed to support the 3rd Armored Division in the fighting in the St. Vith sector in December 1944.

The final airborne operation in the ETO was conducted in March 1945 as part of the Allied offensive over the Rhine River. Several potential airborne operations were considered as part of this campaign of which Operation Varsity was the only one actually conducted. SHAEF tasked the First Allied Airborne Army to plan Operation Jubilant, a potential mission to protect prisoner-of-war camps due to the fear of Nazi atrocities in the final days of the war. The most ambitious proposal in 1945 was Operation Arena, a scheme unveiled on March 12 to deploy XVIII Airborne Corps into the Kassel area behind the German Rhine defenses, establish a defensive zone, then fly in additional infantry divisions for a grand total of ten divisions to create a “New Front” to wage operations into the heart of Germany. Although Eisenhower expressed enthusiasm, the First US Army breakout from the Remagen bridgehead on March 24, 1945, was so rapid that that an airborne operation proved unnecessary. Patton’s Third Army also considered an improvised airborne operation, airlifting infantry over the Rhine in the Frankfurt area using available light liaison aircraft. This also proved unnecessary due to the rapid advance in this sector by more conventional means. Indeed, the airborne element of Operation Varsity took place in spite of crumbling German defenses along the Rhine more due to inertia than necessity. Operation Talisman was dusted off in this period, renamed Eclipse. It was intended to land an airborne force near Berlin in the event of a German collapse, or an airborne assault if the Germans moved the government from Berlin during the Russian siege to some other city such as Munich.

Landing Zone South is crowded with CG-4A gliders and troops of the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment on March 24, 1945 during the Operation Varsity landings north of Wesel. (MHI)

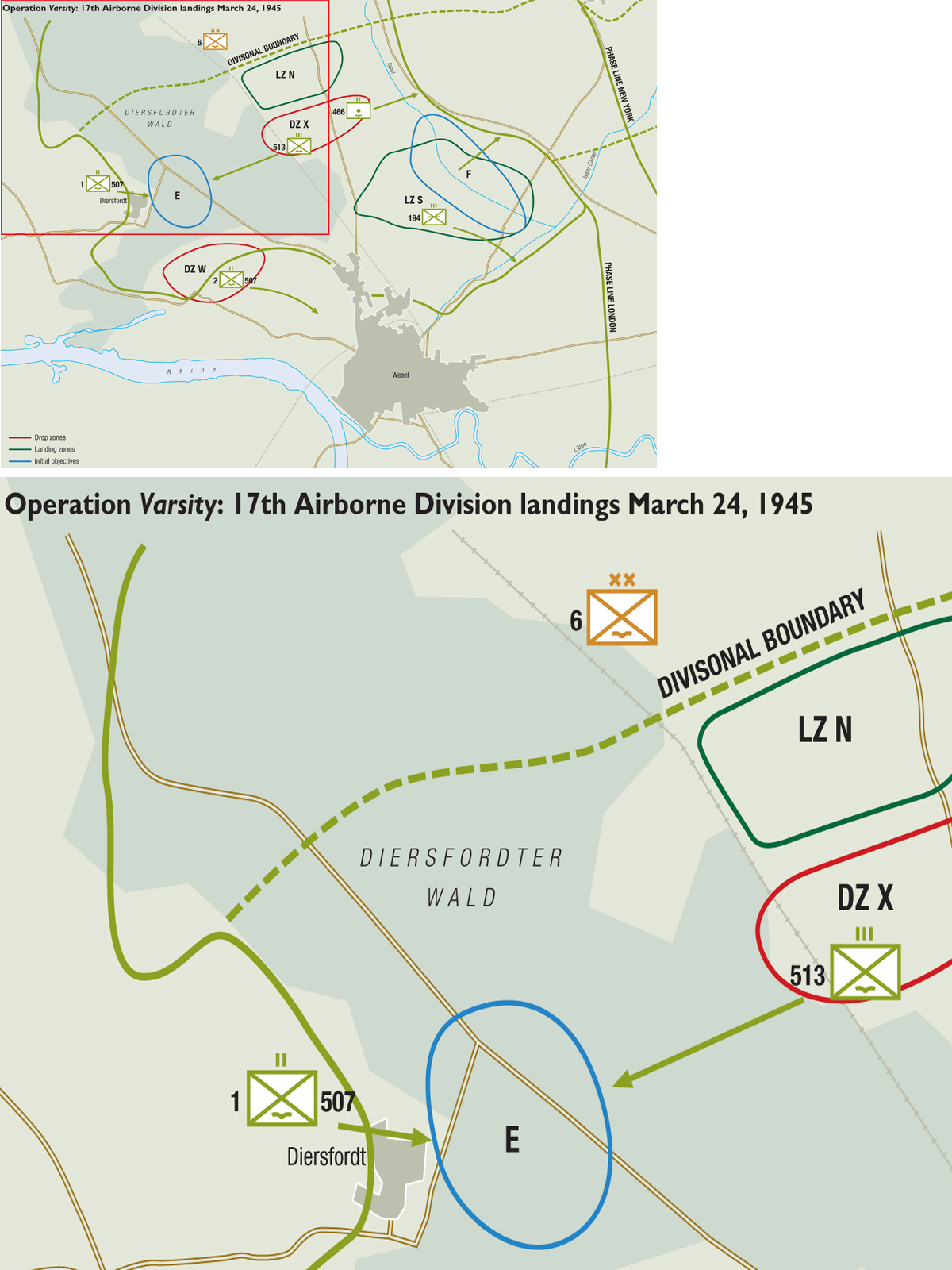

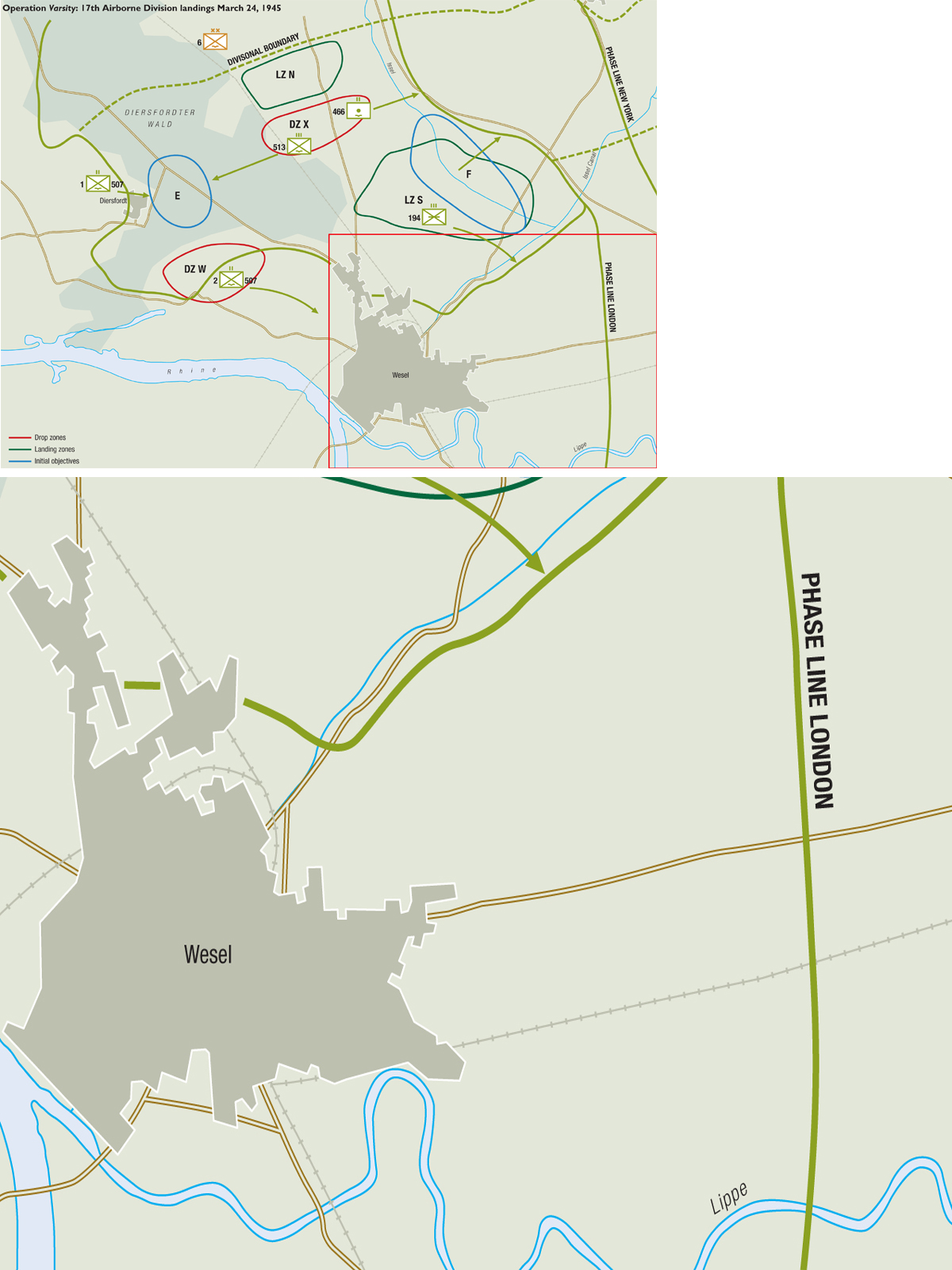

The first staff study for an airborne landing over the Rhine was completed as early as November 7, 1944. The Battle of the Bulge intervened, and Montgomery’s 21st Army Group did not fight its way out of the Reichswald until February 1945, putting it along the Rhine by early March 1945. The initial version of Operation Varsity assumed an airborne landing in advance of Operation Plunder, the main river crossing. This plan included three divisions, the British 6th and US 13th and 17th Airborne Divisions. The first change came when the commander of the British Second Army recommended staging it shortly after Plunder, with an aim to speed the penetration of the German defenses north of the Ruhr around Wesel. Brereton did not want a repeat of the staggered landings of Operation Market, but instead preferred a fast, hard punch, with the main airdrops lasting only four hours instead of several days. Since the troop carrier force had a limited capacity, this meant landing only two divisions, the British 6th and the US 17th Airborne Divisions, instead of the planned three.

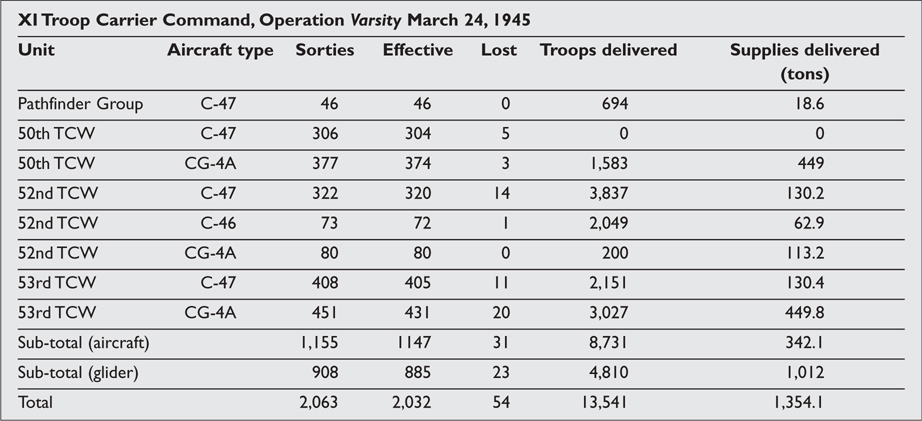

Under the revised Varsity plan, IX Troop Carrier Command provided all the airlift of the 17th Airborne Division as well as the paratroopers of the British 6th Airborne Division, while British squadrons towed the British gliders. To further speed the drop, the mission included a few technical innovations including the first use of double-tow gliders in Northwest Europe, the introduction of the larger C-46 Commando transport in this theater for airborne operations, and the first glider landings conducted without preliminary paratrooper drops on the glider landing zones to secure them. The proximity of First Allied Airborne Army fields in nearby France and Belgium allowed the largest single airborne assault to date with 699 transports and 429 gliders carrying the British 6th Airborne Division from England and 903 transports and 897 gliders carrying the US 17th Airborne Division from France and Belgium. The mission also included a massive aerial support operation including fighter sweeps by 1,253 fighters of the US Eighth Air Force and 900 of the RAF Second Tactical Air Force, with a further 213 RAF fighters escorting the transports from England and 676 fighters escorting the US airlift from France.

Operation Varsity began at 0600hrs on March 24 but, in spite of ample pre-invasion bombardment, the heavy German flak concentrations in the area accounted for 54 US transports and gliders shot down and 440 damaged. The greatest problem was not the heavy flak since the formations dropped the paratroopers at 600ft, but rather the 20mm flak, which accounted for three-quarters of the aircraft damage and losses. The landing areas were tightly bunched and included four paratroop drop zones and six glider landings zones. German troops in the area were mainly from the 84th Infantry Division, which, curiously enough, had fought the 82nd Airborne Division around Nijmegen several months before. By March 1945, it had been badly beaten up by the British XXX Corps in the February fighting in the Reichswald. The drop zones were in the 84th Infantry Division’s rear and contained numerous divisional flak and artillery units as well as support troops. It was being supported by Sturmgeschütz Brigade 394, which had 22 StuG III assault guns and four tanks on hand at the time.

The pathfinder aircraft were led by Col. Joel Crouch, who had helped establish the original pathfinder group, and accompanied by Col. Edson Raff, commander of the 507th PIR, who had led the first paratroop missions in North Africa as well as participating in many of the airborne operations in 1944. The initial jump started at 0953hrs with 1/507th PIR landing about 2,000 yards northwest of the intended Drop Zone W. This was due to poor visibility on the ground caused by smoke pots along the Rhine being used to shield the British amphibious assault mingling with a pall of smoke from nearby Wesel, which had been heavily bombed. This had little consequence, as the battalion’s mission was to secure the western edge of the Diersfordter Woods, which they promptly occupied, capturing a German 150mm artillery battery and numerous prisoners in the process. The following 2/507th and 3/507th landed in DZ W and proceeded to storm Diersfordt Castle, knocking out five German assault guns in the process including two with the new 75mm recoilless rifles. The 464th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion arrived in DZ W around 1000hrs and began shelling German positions in the nearby woods. The regiment had 90 percent of its troops assembled within an hour and half from the first jump. In less than four hours, the 507th PIR accomplished all of its missions against a numerically superior force and in the process captured over 1,000 prisoners.

There was some intermingling of British and US gliders in the congested landing zones of Operation Varsity. In the foreground is an American CG-4A nicknamed “Cornfield Clipper,” while beyond it is a British Horsa and another American CG-4A is to the left. (MHI)

The serials delivering the 513th PIR encountered poor visibility conditions after crossing the Rhine, and the lead C-46 transport of the 313th Troop Carrier Group was set on fire by flak but continued to lead the formation. This formation was particularly hard hit by flak, and the C-46 displayed an alarming propensity to catch fire even after minor hits. The 513th PIR landed about 2,000 yards northeast of DZ X in the area intended for the British 6th Airborne Division. This regiment landed against stiffer resistance than the 507th PIR and spent the rest of the morning clearing resistance as they moved south to their intended objectives. In the process, the regiment captured 1,152 German troops and knocked out three StuG III assault guns and two 88mm guns. The regiment reached the intended drop zone by early afternoon. The supporting 466th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion had the misfortune of landing accurately on DZ X only to find it a hive of German activity. The battalion assembled their howitzers under intense fire and began engaging targets of opportunity. They were assisted by a single stick of paratroopers who had landed in the proper drop zone, as well as glider infantry who had landed in the nearby LZ N. During the course of the fighting, the battalion killed 50 German troops and captured 320, along with 18 machine guns, eight 20mm Flak and ten 76mm artillery pieces. The battalion was in touch by radio with the 513th PIR and was in the curious position of providing fire support towards the paratroopers as they moved southward against German troops, located between the pack howitzer batteries and the regiment.

The 53rd Wing followed with the gliders, beginning the releases over LZ-S around 1030hrs. Flak and small-arms fire was intense and of the 295 aircraft on the way to LZ S, 12 were shot down and 140 damaged. Flak and small-arms fire seemed to be heaviest against the gliders, and only about a third of the gliders escaped being hit but fewer than a half-dozen actually crashed. In spite of the intense ground fire, the landings were accurate, except for one group that landed northwest of LZ S, which fortunately was occupied by other US troops. LZ S was hot, with numerous German infantry, several 20mm Flak batteries, four artillery pieces and numerous mortars. Nine gliders were destroyed on the ground by gunfire and several others were hit on landing by machine-gun fire, wounding most of the glider infantry on board. The 194th GIR fought an intense but disjointed battle to control the landing zone for nearly two hours, finally managing to assemble about three-quarters of its troops by noon. A counterattack was attempted against the southern edge of the landing zone, spearheaded by tanks and StuG III assault guns. The Panzers overran some of the positions of Company G, but four were knocked out with bazookas and the attacks petered out by evening. A patrol was sent southward around dusk to make contact with the British 1st Commando Brigade advancing near Wesel. The Germans staged another attack from the Wesel area around midnight, running into a defensive position manned by an improvised company of glider pilots of the 435th Group reinforced by two batteries from the anti-aircraft battalion. The Germans stumbled into the defenses in the dark and were hit by point-blank fire, with one assault gun and 50 troops being lost in an intense skirmish. While retreating, the German force bumped into another glider infantry position, suffering further losses and bringing the attacks to a halt. During the course of the day’s fighting, the 194th GIR in LZ S took 1,150 prisoners and destroyed or captured ten armored vehicles, two self-propelled flak guns, 37 artillery pieces and ten 20mm Flak guns at a cost of about 50 dead and 100 wounded infantry, and about 20 dead and 80 wounded glider pilots.

The final landing of the attack was by gliders on LZ N, mainly carrying the division’s support troops. The approach to this landing zone was relatively quiet compared to earlier landings as the earlier landings had already overcome most of the heaviest German flak concentrations. However, small-arms fire from LZ N was intense as paratroopers had not cleared the area, which had been the tactic prior to this operation. There were very few German heavy weapons in the landing zone, only a single 88mm flak gun, and the opposition came mainly from support troops of the 84th Infantry Division. Opposition was gradually overcome, mostly by the 139th Engineer Battalion that had been landed by the gliders. By evening, German losses in LZ N were tallied at 83 dead and 315 captured.

The paratroop and glider missions were completed by 1300hrs and were followed by a mission of 240 B-24 bombers dropping a further 582 tons of supplies. The combined US transport total was 8,731 paratroopers, and 4,810 glider troops, and Operation Varsity as a whole had involved 17,000 airborne troops delivered into an area of about 25 square miles in four hours. Gen. Ridgway later concluded that “the concept and planning were sound and thorough, and execution flawless. The impact of the airborne divisions, at one blow, completely shattered the hostile defenses, permitting prompt link-up with the assaulting XII Corps, 1 Commando Brigade and Ninth Army to the south.” The 17th Airborne Division effectively shattered the German 84th Division and, on D+1, mopped up the landing area and pushed the defensive line over the Issel River up to the autobahn to the east. By March 27, German defenses in this sector had largely collapsed, and the British 6th Guards Armoured Brigade moved through the 17th Armored Division positions, with some US troops riding the British tanks into Dorsten.

Casualties in Operation Varsity were moderate due to the crumbling German defenses and the 17th Airborne Division suffered 1,584 casualties including 223 killed, 695 wounded and 666 missing through to March 27, 1945. Operation Varsity was instrumental in disrupting German defenses around Wesel, and subsequently permitted the US Ninth Army to inject the 2nd Armored Division north of the Ruhr industrial zone. This maneuver was a key ingredient in the rapid envelopment of the Ruhr by two US armored thrusts, trapping most of the Wehrmacht’s Army Group B and ensuring the collapse of German defenses in the west.

| Proposed 1945 airborne missions | ||||

| Codename | Planned date | Drop zone | Airborne unit | Mission |

| Arena | March 1945 | Kassel | four airborne, six air-landing divisions | Create “New Front” |

| Amherst | April 1945 | Netherlands | one British airborne unit | Assist 21st AG advance |

| Choker II | March–April 1945 | Worms | 13th Airborne Division | Assist Seventh Army over the Rhine |

| Eclipse | April 1945 | Berlin | Several divisions | Take over Berlin airports in event of government collapse |

| Effective | April 22, 1945 | Stuttgart | 13th Airborne Division | Assist advance |

| Jubiliant | April 1945 | Various | 1+ divisions | Seize POW camps to prevent atrocities |

Although Operation Varsity was by far the best organized and best executed of the wartime airborne operations, it was in other respects the least ambitious. By this stage of the war, the German Army was in serious decline and the operation was conducted against a German force already decimated in previous fighting. The airborne force was landed so close to Allied lines that the first link-ups occurred within hours of landing. It is by no means clear that such an elaborate operation was really needed as similar river-crossing operations were conducted along the US Army fronts further to the south without particular difficulty due to the continuing disintegration in the German defenses.

In the wake of the Varsity success, First Airborne Army kept the newly arrived 13th Airborne Division ready for Operation Choker II, the long-delayed mission to assist the US Seventh Army with a drop behind the Rhine around Mainz; it was canceled on April 4 due to the rapid ground advance and replaced by Operation Effective, a proposed drop into the Black Forest area. In early April, the imminent collapse of the Third Reich led Eisenhower’s headquarters to give Operation Jubilant, a POW rescue mission, precedence over Operation Eclipse, a potential Berlin mission. In the event, none of these operations were necessary due to the collapse of German defenses after the encirclement of the Wehrmacht’s Army Group B in the Ruhr in mid-April and the collapse of Army Group G in the Saar. On May 4, Brereton’s headquarters was asked to prepare a possible mission to land an airborne regiment near Copenhagen to capture the city in advance of the Red Army, but it was canceled due to reports that local forces had surrendered.

Insignia (left to right): 82nd Airborne Division, 101st Airborne Division, 17th Airborne Division, IX Troop Carrier Command.

2 For further details, the combat actions of the 82nd Airborne Division are described in Campaign 115: Battle of the Ardennes 1944 (1): St. Vith and the Northern Shoulder (Osprey: Oxford, 2003) and the 101st Airborne Division in Campaign 145, Battle of the Bulge (2): Bastogne (Osprey: Oxford, 2004).