A1: Fighter pilot, 77th Pursuit Squadron; USA, 1941

This newly commissioned 2nd lieutenant was one of thousands of pilots turned out by the Flying Training Command during the AAF’s massive expansion. The 77th Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor) was then equipped with P-39 Airacobras and based at Hamilton Field, Calif.; its famous ‘poker hand’ insignia dates from 1931. All ‘pursuit’ squadrons were redesignated ‘fighter’ on 15 May 1942. This fledgling pilot wears the A-8 summer helmet with a T-30 throat microphone, B-7 goggles, A-2 jacket with ‘leather insignia’ and name plate, A-4 summer suit, B-2 summer gloves, and ‘moccasin’ style B-5 winter shoes. This ensemble is worn over the standard officer’s wool OD shirt and trousers. Black neckties were replaced by dark OD in February 1942, but continued to be issued until supplies were exhausted. Prior to August 1942 officers’ rank were worn on the shirt’s shoulder straps with the U.S. device and branch of service insignia on the collars.

A2 and A3: Bomber crewmen, 40th Bombardment Squadron; USA, 1941

These B-18A Bolo bomber crewmen are outfitted in the winter B-3 jacket and A-3 trousers adopted in 1934. War-time production jackets were often of ‘two-tone’ construction with some of the panels (sleeve shoulders and undersides, cuff and waist bands, pocket) in dark brown rather than the much darker seal brown. Both wear A-8 winter gloves and A-6 winter shoes. Figure A2 also wears the B-5 winter helmet and B-7 goggle assembly and is trying the fit of an A-7 nasal oxygen mask. The unusual A-7 mask was also used with some early walk-around assemblies. His parachute is contained in the A-3 flyer’s kit bag at his feet. Figure A3 wears the enlisted man’s garrison cap adorned with Air Forces ultramarine blue and golden orange branch of service piping. Units authorised a distinctive unit insignia (crest)1 would wear it in place of the officer’s Air Forces branch of service insignia worn here. He is outfitted with the B-7 back parachute. The A-2 and -3 QAC and S-1 seat types’ harnesses were similar.

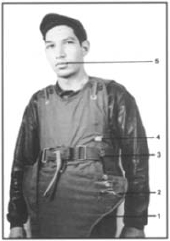

A 36th Troop Carrier Squadron C-47 flight engineer displays the M1 armour vest and M3 apron he wore during Operation ‘Market Garden’: a single 7.92mm bullet struck at point No. 4, and the other points indicate where bullet fragments struck. This photo is part of the series distributed to airmen in an effort to convince them to wear the heavy flak suits.

A4: General Headquarters Air Force shoulder sleeve insignia

The GHQAF was formed on 1 March 1935 as the Air Corps’ first air force and was responsible for the control of heavy bombardment units. The stylised ‘impeller blades’ represented its three original bombardment wings. When the AAF was formed on 20 June 1941, the GHQAF was redesignated the Air Force Combat Command and was now responsible for the four continental air forces’ bomber and fighter commands. Another reorganisation saw the command redesignated Headquarters Squadron of the AAF on 8 March 1942. This patch was approved on 20 July 1937 and was retained through its redesignations until the AAF patch was approved (Plate E4). Organisational patches were worn ½ in. below the left shoulder seam.

B1 and B2: Bomber crewmen, 340th Bombardment Squadron; EIO, 1942

B-17E Flying Fortress crews flying their first missions out of England in August 1942 were ill-equipped with flying clothes. This resulted in a high percentage of cold injuries, increased crew fatigue, and much discomfort and inefficiency due to bulkiness. A typical airman was equipped with the winter B-6 jacket and A-5 trousers, B-6 winter helmet, flying type all purpose goggles, A-10 winter gloves, and A-6 winter shoes. Electric heated items, as worn by Figure B2, were also issued including the F-1 suit, E-1 gloves, and D-1 shoes. Figure B1 is testing the fit of his B-8A oxygen mask; the rebreather bag was highly prone to freezing; he holds an oxygen mask container, and an H-1 emergency oxygen assembly (bail-out bottle) is strapped to his leg. Slung over his shoulder is a high-pressure continuous flow walk-around assembly. Figure B2 wears the popular B-2 winter flying cap. Beside him is an A-1 food container (aircraft) holding four 1 qt. class A type 1 vacuum bottles of coffee; sandwiches were held in the food compartment. Crews were warned that vacuum bottles filled with boiling beverages should not be opened within three hours at 20,000 ft. or six hours at 30,000 ft.—because of the reduced air pressure, the contents would well exceed the boiling point. The 340th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy) was one of the first US units to operate out of England.

B3: Eighth Air Force shoulder sleeve insignia

The ‘Mighty Eighth’ was formed at Savannah, Ga., on 28 January 1942 and soon began deploying to England. The patch (3a), made in England, was originally intended for VIII Bomber Command, which arrived in England in April 1942. When Maj.Gen. Carl Spaatz arrived in England in June, activating the 8th AF there, he accepted the VIII Bomber Command patch for the 8th AF1. On 25 March 1943 the War Department notified field commanders to submit shoulder sleeve insignia designs to the Quartermaster General for approval. The design (3b), approved on 20 May 1943, displayed different style wings.

B4: Bomber crewman, 77th Bombardment Squadron; Aleutians, 1942

This B-26 Marauder crewman is protected against the brutal –40°F encountered in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. The operating conditions were so harsh in the Aleutians that the 77th Bombardment Squadron (Medium), the first B-26 unit committed to combat, lost 18 aircraft to weather and mechanical failure alone in the first year. He is outfitted in the winter B-7 jacket and A-6 trousers, B-2 winter cap, amber Polaroid flying goggles, A-9 winter gloves, and A-10 winter shoes. Medium bomber and fighter pilots operating in other parts of the world generally used lighter ensembles than worn by heavy bomber crews: usually wool or cotton service uniforms worn with or without flying suits and accompanied by an appropriate weight flying jacket. Of course, in winter conditions, full shearling or alpaca flying suits would be donned.

B5: Eleventh Air Force shoulder sleeve insignia

The Alaskan AF was formed 15 January 1942 at Elmendorf Field. On 5 February it was redesignated the 11th AF. Its patch was approved on 13 August 1943.

C1: Transport pilot, 42nd Transport Squadron; Alaska, 1942

This member of the first C-47 Skytrain unit to deploy to Alaska wears the winter B-7 jacket and A-8 trousers, B-6 winter helmet, A-11 winter gloves, and A-12 winter shoes. The B-7/A-6 suit was insulated with mixed chicken feathers and down. He carries an over-and-under .22-cal. rifle/.410 shotgun issued in the types E-2, -8, -10, -12, and -14 emergency sustenance kits, though replaced by the .30-cal. M1 carbine in some late manufacture kits. Beside him is an arctic first aid kit; this, and the similar jungle version, were issued to heavy and medium bomber and transport crews overflying those areas. The Elmendorf Field-based 42nd Transport flew supplies to far-flung American posts throughout Alaska. Transport squadrons were redesignated troop carrier on 4 July 1942.

B-17 waist gunner outfitted with the M3 steel helmet, M1 armour vest, and three-piece M5 groin armour.

C2: Ferry pilot, North Atlantic Wing, 1943

The winter B-11 jacket and A-10 trousers were externally similar to the feather and down insulated B-8/A-9 suit, but alpaca-lined. Under the suit is a knit shirt, a long-sleeve sweater, worn over the wool service uniform for maximum protection on the brutal US-Canada-Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom transatlantic route. This captain wears his service cap with the crown stiffener spring removed to obtain the ‘50 mission crush’ look; more practically, this allowed a radio/intercom HS-38 headset to be worn. Wearing A-7 winter shoes (inserts), he has not yet donned his A-6 winter shoes. He wears an A-7 wrist-watch standardised in 1934.

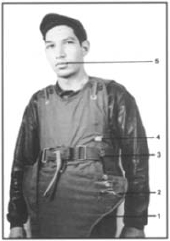

This modification of the M1 steel helmet and liner, developed in the autumn of 1943, allowed the radio headset to be worn comfortably. A screw-jack was used to spread the steel helmet and the helmet liner’s ‘ear’ sections were cut out. Leather flying helmets with earphones were then attached to the steel helmet’s web suspension.

The late war T8 flyer’s armoured helmet, prototype of the M5, was designed specifically to accommodate the headset, goggles, and oxygen mask. The M5 had welded hinges and was made of manganese steel rather than the T8’s Swedish steel.

C3: Air Forces Transport Command shoulder sleeve insignia

Several versions of this patch exist, reflecting the command’s redesignations. The red-white-blue markings around the edge represent Morse code ‘dits and dahs’ and can be found reading ‘ACFC’—Air Corps Ferrying Command (May 1941 to May 1942); ‘AFFO’—Air Forces Ferrying Command (to June 1942); and ‘AFATC’—Air Forces Air Transport Command (to July 1945). The gold-yellow backed patch (3a) was used by the first two commands and the silver-grey one (3b) by the AFATC, though earlier examples often remained in use. The insignia was painted on all the command’s aircraft, and larger ‘squadron-size’ patches were made for flying jackets, along with metal crests for uniforms. The ACFC/AFFC was responsible for delivery of aircraft from factories to units in the States as well as to overseas units and Allies. It was also assigned duties beyond this due to wartime necessity such as cargo transport and operating overseas air routes. It was organised into regionally oriented wings. The Air Service Command (ASC) was also responsible for air transport within the US, while the ‘old’ Air Transport Command took care of tactical transport including parachute and glider operations, causing much duplication of effort. The Ferrying Command and air transport elements of the ASC were merged in June 1942 as the AFATC, to handle all domestic and theatre air transport. The ‘old’ ATC was redesignated the Troop Carrier Command, responsible for tactical operations.

C4: Bomber crewman, 3rd Search Attack Squadron; USA, 1943

Search attack units, along with the more numerous antisubmarine squadrons, operated principally under the First AF’s I Bomber Command to hunt down U-boats off the US East Coast. Initially, all available bombers, attack, and recce aircraft were employed, but the radar-equipped B-18A and B-24 Liberator later became the real sub-hunter workhorses. In October 1942 I Bomber Command was redesignated the Antisubmarine Command. Its 25 squadrons, along with Navy aviation squadrons, virtually eliminated the coastal U-boat threat. In August 1943 the command reverted to its former designation and mission with the antisubmarine role turned over to the Navy, though AAF units still provided assistance. The last of the shearling flying suits to be developed, the winter AN-J-4 jacket and AN-T-35 trousers, remained in use to the war’s end, but only in the States. He wears an A-11 intermediate helmet, A-11 winter gloves, and A-6 winter shoes. To help endure the long, cold, lone aircraft patrols, a 2 gal. thermos container of coffee will be loaded; a similar 1 gal. version was also used. He inspects a 37mm AN-M8 flare pistol carried on all bombers and transports and also issued in the E-11 and -15 emergency kits. The AN-M8 was adopted in early 1943 and came with an A-2 holster and A-5, -6, or -7 cartridge containers, all made of OD duck.

D1: Fighter pilot, 99th Fighter Squadron; Italy, 1944

This P-51 Mustang pilot wears the new intermediate B-10 jacket and A-9 trousers. This early version has shoulder straps and dark brown knit wristlets and waist band. A plastic police whistle is attached to collar, a common practice, to signal rescue boats if down in the water. Under the jacket he wears a C-2 winter vest over his wool service uniform. From August 1942 the U.S. device, formerly worn on the right shirt collar, was replaced with rank, until then, worn on shoulder straps. While many bomber pilots wore neckties, to emphasize their businesslike, behind-the-front-desk job, the more flamboyant fighter pilots dispensed with the tie to allow greater freedom to scan the sky. He also wears the A-11 intermediate helmet, B-7 goggles, and A-11 wrist-watch, standardised in 1940. He wears the overseas rough side out leather service shoes with plain toes. The all African-American 99th, 100th, 301st, and 302nd Fighter Squadrons never lost a bomber they escorted. They were known as the ‘Tuskegee Airmen’, their primary training being conducted at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama; or as the ‘Red Tails’, after their fighters’ tail fin colour, they served as part of the 332nd Fighter and later the 477th Composite Groups. The 477th also included the 616th-619th Bombardment Squadrons with B-25s.

D2: Bomber crewman, 514th Bombardment Squadron; Italy, 1944

The F-2 electric heated suit comprised a simple outer jacket and trousers worn over electric jacket and trouser inserts. The F-1 electric heated felt shoe inserts were designed to be worn inside A-6 shoes. These inserts were also worn with the F-3/F-3A electric suit. The F-2 electric gloves (see Plate D3) were also worn with this outfit. The AN6505–1 aviator’s kit bag replaced the old A-3 flyer’s bag. Based in Italy, the Fifteenth AF’s B-24 units flew many missions into Germany in co-ordination with the Eighth AF launching out of England.

D3: Bomber crewman, 736th Bombardment Squadron; ETO, 1944

The improvements made in clothing available to airmen were reflected in items issued to replacement bomber crews from January 1944: intermediate B-10 jacket and A-9 trousers (here, the late, dark OD version), A-4 summer suit, F-2 electric suit, B-6 or AN-H-16 winter helmet (the latter is worn here), A-11 or A-9 winter gloves, A-12 arctic gloves, F-2 electric gloves (worn here), rayon glove inserts, A-6A winter shoes, and F-1 electric shoe inserts. Waist gunners were additionally issued the winter B-11 jacket and A-10 trousers, while ball turret gunners were equipped with F-2 electric felt shoes. This B-17F radio operator, manning a 65 lb., upward firing .50-cal. M2 flexible machine gun (with a 100-round ammo container), is also outfitted with the B-8 goggles (issued in kit form with interchangeable clear, green, and amber lenses), A-10R oxygen mask attached to an extension hose, H-2 emergency oxygen assembly, and A-4 QAC parachute harness (chest pack removed). The B-9 back and S-5 seat types’ harnesses were similar in design. A flak suit would be worn over all this. On the floor is a low-pressure continuous flow walk-around bottle.

D4: Mediterranean Theatre of Operations air forces’ shoulder sleeve insignia

Three air forces deployed to the MTO during the war’s course. (4a) The Ninth AF was formed from the 5th Air Support Command on 8 April 1942 at New Orleans Army Air Base, La. Its advance elements deployed to Egypt in June as the US Army Middle East AF. Its main elements arrived in November to conduct missions throughout the eastern Mediterranean, Italy, and the Balkans. In October 1943 it deployed to England and reorganised as a tactical air force to support ground forces after the invasion. Its patch was approved on 16 September 1943. (4b) The Twelfth AF was formed at Bolling Field, DC, on 20 August 1942, deployed to England, and supported the North African landings in November. It operated from Tunisia throughout North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and Southern France. The patch was approved on 1 December 1943. (4c) The Fifteenth AF was formed from the Twelfth’s XII Bomber Command in Tunis, Tunisia, on 1 November 1943. The next month it moved to Italy from where it flew missions into Germany and the Balkans. Its patch was approved on 19 February 1944.

E1: Recce Pilot, 14th Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron; ETO, 1944

The intermediate B-15 jacket and A-11 trousers were to remain the standard flying suit through the remainder of the war. An AAF patch is printed on the left shoulder. This F-5 pilot wears the AN-H-16 winter helmet, A-11A winter gloves, and A-6A winter shoes. Fighter type recce aircraft had heated cockpits, eliminating the need for electric suits. He holds an aeronautic first aid kit provided in all aircraft. The A-13 oxygen mask was of the pressure-demand type permitting ascent above 40,000 ft., a necessity for the extremely high altitudes required for recce missions. There were a wide range of different types of recce squadrons, which went through a bewildering series of redesignations. They were equipped with recce variants of standard aircraft, fitted with cameras and extra fuel tanks and with most armour and guns removed: F-3 (A-20A), F-4 and -5 (P-38E), F-6 (P-51), F-7 (B-24J), F-9 (B-17F), F-10 (B-25D), and F-13 (B-29A). Recce units provided both pre- and post-strike recce, conducted aerial mapping, and supported ground forces with tactical reconnaissance.

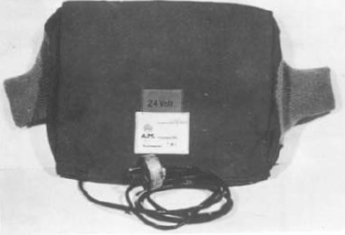

The Eighth AF developed electric heated casualty bag. The bag is open, but can be closed and secured by tie-tapes. Four were carried in heavy bombers.

E2: Bomber crewman, 748th Bombardment Squadron; ETO, 1944

The two-piece F-3 electric heated suit was designed to integrate with the A-15/A-11 suit. Q-1 electric heated shoe inserts were worn over standard service shoes and inside A-6A winter shoes. F-2 electric gloves completed the ensemble. The popular highneck sweater is worn over the wool service uniform and wool long underwear. An FTG-3 food storage container (also called a Tappan B-2 food warmer) was authorised on the basis of two per very heavy and heavy bombers and one per six men, or fraction thereof, on smaller bombers, though intended for B-29s. It held 12 1 pt. cups and six four-compartment trays in their own heated compartments, and had a drawer for sandwiches, condiments, and utensils. The warmer was plugged into the aircraft’s power system as used for the electric suits. The B-2 was not too successful due to cleaning problems, and the reheated food was considered unpalatable; crews preferred simple sandwiches and coffee.

E3: Bomber crewman, 335th Bombardment Squadron; ETO, 1945

In late 1944 combat units received a massive replenishment of clothing stocks, which rendered inadequate clothing a negligible factor in causing frostbite. The intermediate B-15A/A-11A suit, worn over an F-3A electric suit, offered a number of refinements over the A-15/A-11. The AN-H-16 winter helmet, B-8 goggle, and A-14 oxygen mask comprise the head assembly. The mask’s hose is attached to an AN6020-1 low-pressure demand walk-around unit, clipped to a tab; it is also attached to an H-2 emergency oxygen assembly. F-2 electric gloves and F-2 electric heated felt shoes complete the protective clothing. An AN6519-1 life vest (same as a B-4), with a sea dye marker packet, is worn under a B-10 back parachute harness. The A-5 QAC and S-6 seat type harnesses were similar. A parachute first aid kit is strapped to the harness. This navigator double checks his calculations on an E-6B aerial dead reckoning computer.

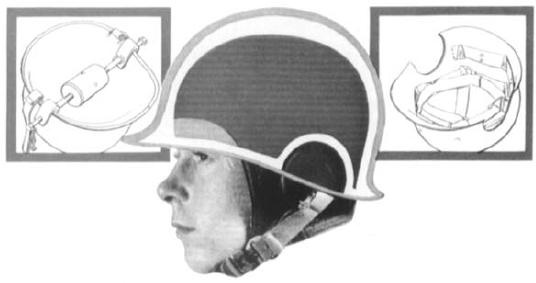

The Eighth AF developed 24 volt electric heated muff. The British Air Ministry contract tag is affixed under the 24 volt identification tag. Five of these were required to be carried in heavy bombers.

E4: Army Air Forces shoulder sleeve insignia

(4a) This patch was approved on 19 March 1942 for wear by all AAF units and organisations. Gradually, numbered air forces and some other organisations replaced it with their own designs. It was retained by all those not authorised a designated insignia. (4b) The comparatively rare reversed colour AAF patch appears to be a semi-official variant worn on both OD and khaki uniforms at the individual’s discretion.

F1: Bomber bail-out, 1943

This B-17E crewman is exiting from the tail gunner’s emergency hatch. He wears an A-2 QAC parachute displaying the back pad and an AN-R-2A one-man raft parachute pack case. All emergency parachutes were manually activated by pulling a ripcord. Airmen were advised to delay their opening for two to six seconds to ensure they cleared the aircraft; this also served to slow their falling speed, thus reducing opening shock. From high altitudes, airmen were advised to freefall to a lower altitude before opening. This sped the airman’s descent through the intense cold and rarified air at high altitudes, even though he might possess a bail-out bottle and protective clothing; a long parachute ride at high altitudes could be debilitating or even fatal. It was also safer to freefall through a layered bomber formation, and effectively prevented attack by enemy aircraft. In 1944 an automatic opening device was developed for the A-3 QAC parachute and saw limited use. This device’s aneroid-activated switch automatically opened the parachute at a pre-set altitude in the event of the airman being disabled.

F2: Water landing, 1944

The B-3, -4 (worn here), and -5 life preserver vests were worn under the parachute harness, here a B-8 back type, which had to be shed prior to activating the CO2 cylinders or the wearer’s chest would be crushed. Besides the obvious hazards of a water landing, a major concern was entanglement in suspension lines and/or canopy. Airmen were instructed to release their harness fastenings prior to landing, keeping their arms tucked into the sides to prevent falling out, and throwing them upward when hitting the drink. The jumper would then slide out the harness and swim upwind or up current away from the discarded parachute.

F3: Fighter bail-out, 1945

Fighter pilots, in these pre-ejection seat days, would attempt to turn the aircraft over, jettison the canopy, release the lap belt and shoulder harness, and kick themselves out. Oxygen mask hose and headset wires would disconnect if the pilot failed to do it. In combat, this form of bail-out was a relative luxury. This P-51 pilot wears a B-5 seat parachute with its seat cushion. A C-1 emergency vest is carried in a modified (with strap, snap hook, ‘V’ ring added to its back) M1936 field bag attached to the harness.

G1: Developmental flyer’s body armor, 1943

The first flak jackets issued were the contract, Britishmade prototypes. Here, the fully armored Type A full vest and Type C tapered apron are worn. These were soon redesignated the T1 and T3, being standardised as the M1 and M3 respectively in October 1943. The Type B half vest had an unarmored back for wear by pilots and the Type D apron was of a square design. These were redesignated the T2 and T4 and standardised as the M2 and M4. The M3 steel helmet was a modified M1 with ear protectors and headset cut-outs.

G2: Issue flyer’s body armor, 1944

This gunner wears the standardised M1 full vest and M4 square apron. He also wears the leather covered M4 steel, or ‘Grow’, helmet modeled after the British version. The red web pull strap activates the quick release system.

G3: Issue flyer’s body armor, 1945

This B-29A Superfortress pilot is outfitted for high altitude operations in the M2 half vest and M5 groin armor, a three-piece assembly providing increased protection. The M5 steel helmet was similar to the earlier T-8. He also wears the AN6530 goggles (same as B-8), A-14 oxygen mask, H-2 bail-out bottle, B-15A/A-11A suit, and A-11A gloves. He is secured in his armored seat by a B-14 lap safety belt and B-15 safety shoulder harness. These were standardised in 1944 to replace the B-11 lap belt and various shoulder harnesses in all fighter, bomber, and transport pilot’s and co-pilot’s seats.

A staff sergeant demonstrates the vest type emergency kit, the experimental predecessor of the C-1 flyer’s emergency sustenance vest. This test version had small tubular pockets at the front opening and collar. He sits on an S-1 seat parachute and C-2 one-man raft case.

G4: Modified flyer’s steel helmet, 1944

Though replaced by improved designs, unit-modified M1 steel helmets remained in use. Occasionally, an airman would personalise his helmet; this one was used by a B-26 tail gunner in the 323rd Bombardment Group. Mission number and target name were pencilled on the bombs.

G5: Issue flyer’s steel helmet, 1944

The M4A2 steel helmet was one of the most widely worn flyers’ armoured helmets. The M4A1 helmet was of identical design, but the A2 was made slightly larger. All models were worn over shearling flying helmets and were designed to integrate with headsets, goggles, and oxygen masks.

H1: Fighter pilot, 44th Fighter Squadron; Pacific, 1943

The A-4 summer suit was the standard flying suit until replaced by the AN-S-3 and -31. This P-40 Warhawk pilot on Guadalcanal wears the A-8 summer helmet, B-7 goggles, and B-2 summer gloves. To accompany him on his mission he has a sack lunch, 1 qt. M1910 water canteen, and 1 pt. class B type 1 vacuum bottle of coffee (also available in 1 and 2 qt. capacities). He carries a .38-cal. S&W Victory Model revolver in a Navy issue shoulder holster traded from a Marine aviator.

H2: Fighter pilot, 402nd Fighter Squadron; ETO, 1944

The AN-S-31 summer suit was intended to replace the A-4, but the older suit remained in use through the war. Worn over the AN-S-31 is the Clark G-3 fighter pilot’s pneumatic, or anti-G, suit. The later G-3A was based on this suit rather than the Berger G-3. This P-38 Lightning pilot carries the anti-G suit’s carrying case and wears B-3 summer gloves. The AN-H-15 summer helmet proved to be unsatisfactory and was replaced by the similar A-10A. He is also outfitted with two British-made items used by many UK-based fighter pilots throughout the war: the Mk IV goggles (with the flip-down anti-glare lens removed) and a dull yellow Mk I life jacket.

H3: Bomber crewman, 8th Bombardment Squadron; Pacific, 1944

This B-25 Mitchell crewman, operating out of New Guinea to attack Rabaul, is outfitted in the L-1 light suit, A-10A summer helmet, B-8 goggles, and B-3A summer gloves. The K-1 very light suit was of the same design but made of khaki Byrd cloth. He carries a leather organisation equipment list container holding his aircraft’s extensive roster of on-board gear.

H4: Asiatic-Pacific Theater of Operations air forces’ shoulder sleeve insignia

Five air forces operated in the Pacific and Asia. (4a) Originally formed as the Philippine Department AF on 20 September 1941, the 5th AF was activated on Java on 5 February 1942. It fought throughout the Southwest Pacific and later moved to Okinawa to attack Japan. Its patch was approved on 25 March 1943. (4b) The 10th AF was activated at Patterson Field, Ohio, on 12 February 1942 and moved to India. It operated in Burma and China, later moving up to that front. The patch was approved on 25 January 1944. (4c) The Thirteenth AF was formed on New Caledonia on 13 January 1943 to operate in the Central and Southwest Pacific. Its patch was approved on 18 January, 1944. (4d) The Fourteenth AF was formed from the China Air Task Force (formed in mid-1942) on 10 March 1943 at Kunming, China. It flew operations from Burma to Japan. The patch was approved on 6 August 1943 reflecting its origins in the old ‘Flying Tigers’. (4e) The Twentieth AF was activated at Washington, DC, on 4 April 1944. Equipped solely with B-29s, its mission was to bomb Japan into submission. Elements first launched out of China, but later the entire force operated from Pacific islands. Its patch was approved on 26 May 1944.

The orange-yellow B-4 pneumatic life preserver vest with shark deterrent and dye marker packets attached. An opened blue ‘shark chaser’ packet is to the left of the vest. The B-3 and AN6519-1 vests were identical in appearance.

I1: Fighter pilot, 1st Fighter Squadron (Commando); Asia, 1944

The Tenth AF’s 1st and 2nd Air Commando Groups included some of the more nondescript flyers in a branch that tended to foster non-adherence to uniform regulations. This P-51 pilot wears a self-camouflaged AN-S-3 summer suit, Australian bush hat, D-1 goggles, A-11 wrist-watch, and Wellington boots. Even his M7 shoulder holster, with a pearl-handled .45-cal. M1911A1 pistol, is worn as a belt holster. He is placing one of the flasks of the E-17 personal aids kit in his pocket.

I2: Flying jacket art

The artwork painted on the backs of flying jackets, especially the A-2, whether utilitarian or fanciful, depicted squadron insignia, boastful victory slogans, scantily clad pinups inspired by movie goddesses (Glory Girls), duplications of aircraft nose art, and threats of vengeance to be inflicted on the enemy. Headquarters sometimes attempted to ‘clean up’ the usually nude ladies on which nose art often focused, but the crews who complied only added negligées or G-strings. (2a) The approved insignia of the 90th Bombardment Group (Heavy) ‘Jolly Rogers’ was repeated on the tails of its B-24s. He also wears a B-1 summer cap and flying sun glasses (comfort cable type). (2b) The ‘Wild Children’ of a 390th Bombardment Group (Heavy) B-17 crew display their bomber’s nose art along with their completed missions and kills. (2c) ‘Dark Lady’ replicated the nose art of a P-61 Black Widow night fighter in the VII Fighter Command. He wears the E-1 dark adaptation goggles1.

J1: Anti-exposure suit, 1944

The R-1 quick-donning anti-exposure suit kept the flyer dry and afloat, but relied on flying clothes worn underneath to provide the necessary insulation from frigid waters. The hood and boots were integral, but the one-finger F-1 exposure gloves were stowed in the pockets. He also wears a water-resistant helmet supplied in the E-11 emergency kit. He has ignited a Mk 1 Mod 1 distress smoke hand signal.

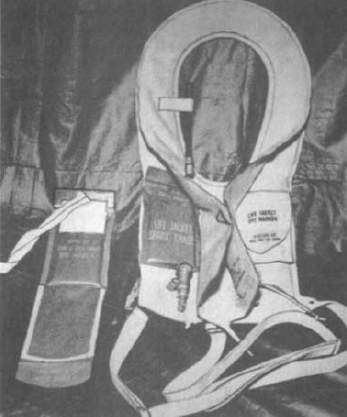

J2: B-4 life preserver, 1943

This B-4 life preserver vest (B-3 and AN6519-1 were externally identical) has dye marker and shark deterrent packets attached to it. It was common for the life vest technical order number, inspection dates, and the crewman’s name to be stencilled on the front panel. This airman wears a water-resistant helmet, found in some emergency kits, and a wartime production ‘two-tone’ B-3 winter jacket. He holds an A-9 hand energised flashlight, a component of multiplace life rafts.

J3: B-5 life preserver, 1945

The later B-5 life preserver vest offered pockets for a Navy attachable light (pinned to his shoulder), plastic police whistle, and dye marker; an ESM/1 signal mirror and shark deterrent packet could be added. He holds an AN6522-1 emergency fishing kit container, which could be donned as a chest apron. He wears a B-1 summer cap, K-1 very light suit, and K-1 mosquito-resistant very light gloves.

J4: C-1 emergency vest, 1944

The C-1 flyer’s emergency sustenance vest contained a surprising quantity of survival aids. A .45-cal. M1911A1 pistol is held in its integral holster. He wears an emergency reversible sun hat and H-1 eye protective goggles, both components of the vest. He also wears an A-9 summer suit, rayon glove inserts, and holds an M75 handheld, two-star signal flare, a component of the C-2 one-man raft.

J5: Emergency radio transmitter

The AN/CRT-3 radio, known as a ‘Gibson Girl’ due to its shape, was the last model issued; the others were the very similar SCR-578A and B. These were provided in multiplace life rafts and packed in a container with two ballons, chemical hydrogen generators, a kite (to hoist the antenna wire aloft) and accessories. The 9×11×12 in., 34–38 lb. radios had a 50–300 mile range.

This technical sergeant models an inflated B-5 life preserver vest revealing its improved retaining strap system and accessory pockets containing an attachable light, police whistle, and dye marker.

K1: Walk-around and bail-out oxygen assemblies

Portable (walk-around) and emergency (bail-out) oxygen bottles were crucial gear for airmen operating above 10,000 ft. See the Oxygen Cylinder Assemblies section for details. A 12 in. ruler is provided for scale. (1a) High-pressure continuous flow walk-around assembly. (1b) Low-pressure continuous flow walk-around assembly. (1c) Low-pressure demand walk-around assembly. (1d) AN6020-1 low-pressure demand walk-around unit. (1e) Regulator and cylinder assembly-diluter demand oxygen. (1f) H-1 emergency oxygen cylinder assembly. (1g) H-2 emergency oxygen cylinder assembly.

K2: In-flight and emergency rations

A number of special rations were available to airmen for inflight meals and survival situations. (2a) The 1934 emergency air corps ration had three 4 oz. enriched chocolate cakes in a key-opened, galvanised container, which could be used to hold water. It was originally issued as part of B-1, -2, and -3 parachute emergency kits, but was later replaced by (2f), and still later by (2g). For individual issue it was superseded by (2b), but still issued into 1944. (2b) The type D field ration had three 4 oz. vitamin-enriched, tropical chocolate bars (would not melt in high temperatures) in a pasteboard carton. A bar could be boiled in a canteen cup of water to make cocoa. Fighter pilots were often issued one D ration per mission. (2c) Seven units of 1945 type A life raft rations were provided as a component of multiplace rafts. Its key-opened can held 12 packages of Charms candy, 18 pieces chewing gum, and six vitamin tablets (1942 versions had eight Charms and two packages of gum). It provided six man-days of (albeit meagre) rations when consumed with at least one pint of water daily. It replaced (2f) as standard life raft rations in 1942. (2d) AN-W-5 emergency drinking water, with a distinctly metallic taste, was supplied in 11 oz. cans with a screw cap. Early raft stocks had seven cans, but only one can was supplied when the JJ-1 and LL-1 desalting kits became available in 1944. Cans were also included in many of the E-series emergency kits. (2e) The type JJ-1 sea water desalting kit contained six chemical briquettes and a vinylite bag. One briquette, mashed up in the bag, would desalt a pint of water. (The LL-1 kit was a much larger solar still assembly.) (2f) The infamous 1941 type K field ration consisted of three meals, each contained in an outer pasteboard carton and an inner waxed box (early cartons were colour-coded in a ‘camouflage’ pattern, but from 1943 most were natural pasteboard). This was the standard combat ration for all branches throughout the war. A meal contained two small, key-opened cans of various meat products and cheese spread; various combinations of ready-to-eat cereal, chocolate, and fruit (could be boiled to make a jam) bars; hard and soft crackers; packets of soluble coffee, sugar, lemonade powder, chewing gum, dextrose tablets, and bouillon cubes. Toilet paper, four cigarettes, book matches, salt tablets, and a tiny wooden spoon were also provided. K rations were a component of parachute emergency kits, until replaced by (2g)—K’s provoked thirst—and many of the E-series emergency kits. An E-6 (rations) emergency kit (individual bail-out) is displayed; the E-7 (water) bail-out kit was identical. (2g) The emergency parachute ration was adopted in 1943 to provide a more compact alternative to K-rations, replacing them in emergency parachute kits and also found in the C-1 flyer’s emergency vest. The can held two bouillon cubes, cheese and cracker bar, Charms candy, six pieces chewing gum, two chocolate bars, two packets soluble coffee, two sugar tablets, 15 halazone tablets, and four cigarettes. A ‘P-38’ can opener was taped to the can. (2h) The air crew lunch, adopted in 1944, held two fudge bars, two sticks chewing gum, and 2 oz. hard candies. These were contained in a pocket-size, two-compartment pasteboard carton with a sliding cover allowing its contents to be dispensed with one hand. It was issued on the basis of one per man on missions of more than three hours duration. On missions longer than six hours, crews were supplied with full meals of sandwiches (Spam being ‘immensely popular’), snacks, canned fruits and juices, and hot soups and beverages.

A C-2 one-man parachute raft with its component MX-137/A radar reflector erected. The raft is orange-yellow with a medium blue spray shield fitted.

L: Hell at 25,000 feet

Ideally, a disabled aircraft requiring the crew to bail out was set on a level course and slowed down. The realities of bail-out from a battle-damaged aircraft were far different, however. When spinning out of control, the resulting G-forces, often coupled with fire and airframe break-up, made bailing out a perilous and often impossible ordeal, with few surviving airmen admitting recalling details. The bail-out bell has rung, and these airmen struggle to make it out their designated emergency exits. These desperate young men wear alpaca-lined B-10/A-9 intermediate suits, with the exception of the right waist gunner (L1), who has retained his old B-6 ‘crusty’ and is shedding his flak suit (M1 vest, M4 apron). His wounds treated, the contents of an aeronautic first aid kit litter the floor beside his M3 steel helmet. An electric heated muff has been slipped on his arm in an effort to protect it from the extreme cold. His mask hose is plugged into a low-pressure demand walk-around assembly. The left waist gunner (L2) rushes to snap on his A-4 QAC parachute. The .50-cal. M2 flexible machine guns, to protect the B-17E from lateral attack, are fitted with the old gun-mounted 200-round ammo containers; larger hull-mounted containers were introduced later. The radio operator (L3) armed with an A-17 carbon dioxide fire extinguisher, emerges from his fire-engulfed compartment wearing a B-8 back parachute. Already disconnected from the aircraft’s oxygen system, he is activating his H-2 bail-out bottle. A discarded A-2 carbon tetrachloride fire extinguisher lies on the floor.

The crew of the ‘Memphis Belle’, 324th Bombardment Squadron, after completing its much publicised 25th mission in May 1943. This was the first crew to complete the required 25 missions (later increased to 30). The crew had amassed 51 decorations, but only the tail gunner received a Purple Heart. Unlike the motion picture of the same name, the ‘Belle’s’ actual 25th mission was uneventful.

1 Groups and higher units were authorised crests, which were worn by subordinate squadrons. The authorisation of crests was ceased in 1943 to conserve materials.

1 On 18 September 1942 air force designations were changed from Arabic numbers to fully spelled out, e.g. the 8th AF became the Eighth.

1 ‘Dark Lady’ jacket information provided courtesy of Robert G. Borrell, Sr.