THE ACCELERATION OF THE “PACE OF LIFE” AND PARADOXES IN THE EXPERIENCE OF TIME

AS GEORG SIMMEL HAD ALREADY remarked in 1897, “one often hears about the ‘pace of life,’ that it varies in different historical epochs, in the regions of the contemporary world, even in the same country and among individuals of the same social circle.”1 Just as little has changed in this respect, as in the related fact that this pace continually escalates in modern society, so that each of its periods can successively claim to live at a historically unprecedented record pace.2 As we have seen in part 1 of this study, this realization has almost always been accompanied by the fear that the pace of life has gotten too fast. Unfortunately, however, despite all the time use studies we have, the question how to measure it and thus how to empirically test the acceleration thesis is just as unclear today as in Simmel’s time.

Simmel himself suggested that the pace of life be defined as the “product of the number and intensity” of the changes in the ideational contents of consciousness per unit of time,3 a definition that is, although intuitively plausible, as curious as it is empirically unoperationalizable. He conjectured that this tempo correlated with the available quantity of money and its speed of circulation.4

In an award-winning social-psychological study in which the pace of life of large cities in thirty-one different countries from four regions of the earth was measured, the Californian sociologist Robert Levine and his team proposed another definition of the speed of life, one relatively easy to operationalize empirically. According to their definition, the respective culturally determined tempo of life can be established using three indicators: “First, we measured the average walking speed of randomly selected pedestrians over a distance of 60 feet. . . . The second . . . focused on an example of speed in the workplace: the time it took postal clerks to fulfill a standard request for stamps. . . . Third, as an estimate of a city’s interest in clock time, we observed the accuracy of 15 randomly selected bank clocks in main downtown areas in each city.”5 This definition has the advantage of allowing accurate intercultural comparisons that actually do generate several interesting results.6 Nevertheless its methodology appears rather dubious and its empirical relevance quite limited. In particular, the question what is actually being measured thrusts itself on us: the pace of social life? The selectivity of the indicators already speaks against this. Post offices in New York are, as the author knows from painful experience, unusually and, in comparison with European standards, even scandalously slow, something presumably connected with the low estimation and chronic underfinancing of the public sector in the United States.7 Yet to take this as an indicator of an overall slow pace of life in that metropolis appears rather questionable. Conversely, the surprising fact that the Irish show the highest foot speed could possibly be explained not by their generally fast pace of life but by the frequent rainy weather in Ireland.8 Therefore, in order to adequately take into account the temporal peculiarities of particular cultural practices while determining the pace of life, the action tempo of an entire series of very diverse processes from different fields of action must be considered and aggregated.

The question concerning what exactly is being measured is also emphatically raised, however, with respect to Levine’s third indicator. Karlheinz Geißler has observed that clocks in the public realm, and in particular at the nodal points of metropolitan life like modern airports, are increasingly losing significance and disappearing from the streetscape (or falling into neglect). If that is correct,9 then the suspicion arises that the precision of public clocks might rather be a sign of backwardness, of being stuck inertially in “classical” modernity, rather than one of arrival in the quick-paced “postmodernity.”10 Finally, Levine’s indicators in and of themselves say nothing about the “condensation” of action episodes and subjectively felt time pressure, which play a constitutive role for at least the subjective perception of a high tempo of life and are not at all connected in a linear way with the performance tempo of individual actions. Whoever is in a position to perform an action faster than others may thereby precisely decelerate her life: but only provided that she uses the freed-up time resources for breaks or recuperation.

Due to these kinds of difficulties, I proposed in chapter 2.2c that the acceleration of the pace of life be defined as the increase of episodes of action and/or experience per unit of time as a result of a scarcity of time resources. I then separated it into an objective and a subjective component. Objectively, at least in principle, the condensation of episodes of action and/or experience can be measured by means of time use studies, while subjectively the experience of stress, time pressure, and “racing” time are empirically ascertainable indicators for the perception of a scarcity of time resources and an accelerated elapse of time.11 The acceleration of the pace of life contains, then, an increase in the aggregated speed of action as well as the transformation of the experience of time in everyday life.

In what follows I will first investigate the manifestations of and evidence for an objective condensation of episodes of action and experience in order to then return in greater detail to the question of the subjective feeling of time pressure, the perception of time resources, and the tempo at which time transpires. In the last section of the chapter I work out a further dimension of the acceleration of the pace of life, which remains hidden at first, one that goes beyond modes of action and experience and relates to “modes of being,” i.e., socially constitutive forms of identity. Their transformation turns out to be a cultural consequence of the acceleration of social change and the pace of life. It therefore represents a necessary effect of the “circle of acceleration” that will be presented in chapter 6 as a kind of summation of the previous considerations.

1. OBJECTIVE PARAMETERS: THE ESCALATION OF THE SPEED OF ACTION

In the dimension testable by the methods of quantitative empirical social research, the thesis of an acceleration of the pace of life postulates a heightening of the number of episodes of action and/or experience per unit of time. To this end, there are in principle three different but combinable strategies available: first, action itself can be accelerated (walk, eat, read faster); second, breaks and idle times can be reduced or eliminated; and, third, several actions can be performed simultaneously (multitasking). In their time use study Robinson and Godbey describe such strategies as “time-deepening” and add to them a fourth, namely, the replacement of slow activities by faster ones, for instance, cooking by calling for takeout pizza.12

In its general form, the thesis defended here states that since the beginning of modernity the average pace of life has accelerated, though not in linear fashion but in phases interrupted by pauses and small trend reversals.13 By themselves, the length of the work day and the quantity of time free outside work tell us nothing about the pace of life. If people worked up to fourteen hours a day in early modernity, this does not mean that the speed of action and experience was particularly high. Presumably it was quite low, although long work hours may compel a thickening of action in the scarce hours of free time. On the other hand, the intensification of work and the closure of the “pores of the workday” observed by Karl Marx in the first volume of Capital form a splendid example of the first and second aforementioned strategies of acceleration; they are a direct consequence of the shortening of the workday.14 Here, at the very least, the work-related tempo of life heightens as a direct result of the shortening of labor time in the capitalist economy, whereas the pace of life in leisure time is not correlated with the latter’s length: it can sink or rise while leisure time increases; however, it displays a tendency to rise when material well-being does.15 Insofar as feelings of time pressure and stress are indicators of an acceleration of the pace of life, their measurable increase alongside a shortening of work time in Western societies should not be surprising. The contradiction between these two quantities (growing stress despite rising free time), overemphasized by Robinson and Godbey, proves to be merely apparent after a closer analysis.

Numerous and diverse examples of all three (or four) strategies of temporal condensation can be found in everyday life, essays and op-eds, and works of cultural criticism. They run from guides to “power naps” and shortened and condensed “quality time” with the kids in the evening to speed reading and speed dating (a form of coupling in which potential “dates” are encountered, as it were, on an assembly line) on down to the drive-through funeral. English names are usually used for such innovations, perhaps because Americans are pioneers in this area too. Furthermore, one finds reports about the widespread tendency of, e.g., the length of performances of classical symphonies and plays as well as news reports on television and the radio to become shorter and shorter.16 Even the speed of our talking has supposedly accelerated significantly: while this intuitively makes sense for radio and television and is surely easy to verify,17 the result of a study by the political scientist Ulf Torgersen showed that the number of phonemes articulated per minute in the yearly budget debates of the Norwegian parliament continually rose between 1945 to 1995 from 584 to 863, an increase of almost 50 percent.18

As suggested above all by the works of Gerhard Schulze,19 the pace of life, in particular in late modern society, is determined not only by the number of (active, objectively measurable) episodes of action but also by the quantity of (even passive, subjective) episodes of experience. For while not all experiences can be qualified as actions,20 it is precisely the former whose quality and quantity make up the center of social life in the “experience society,” according to Schulze, and provide it with, as it were, a focus for the definition of the good life: the cultural maxim of this society runs, if we follow Schulze, the more episodes of experience that can be savored for the enrichment of one’s inner life in less time, the better.21 However, independent of the question concerning this foundational cultural project (to which I will return in chapter 7.2), the thesis of the acceleration of the pace of life states that the number of episodes of experience per unit of time also increases, hence a kind of “compression of experience” occurs.

It is obvious that just such an idea already lay behind Simmel’s definition of the tempo of life when he connects it to the heightening of the number and contrast of changing contents of consciousness. We can find a form of this compression of experience in, for instance, the shortening of the duration of ads on CNN in 1971 to 30 seconds, a brevity that was relatively avantgarde at the time, although today they only last 5 seconds. Thus the viewer is exposed every 5 seconds to completely different “contents of consciousness,” each with their own fragments of narrative structure.22 The switching is still faster in the case of contemporary TV “grazers,” who change the channel on average every 2.7 seconds.23 Someone who watches an ad-free channel for a while finds herself exposed to image editing that is essentially faster than it was even in the 1970s, for instance. If we assume Simmel’s definition and an average length of time watching television of two hours per day, this finding can already be interpreted as a significant indication of an acceleration of the pace of life: from this perspective, the phenomenon observed with astonishment by Robinson and Godbey, namely, that the more time people spend in front of the television, the more they seem to complain about stress and lack of time, hardly seems paradoxical.24

Naturally one difficulty here is that it is unclear what can count as a self-contained episode of experience. Insofar as experiences are always also defined by their context and need narrative closure from subjects,25 it may appear implausible to define every new ad or every narrative sequence as an episode of experience. But, even if one uses a broad definition of experiences, the assumption of a steady escalation of their episodic density remains plausible. The temporal structures of late modernity seem to be characterized in large measure by fragmentation, i.e., by the breaking down of series of actions and experiences into ever smaller sequences with shrinking windows of attention. Eriksen sees here an outstanding marker of the late modern “tyranny of the moment” that is caused by permanent availability for communication (and hence vulnerability to a variety of external interruptions), the flexibilization and deinstitutionalization of practices, and also excess information and material abundance. This creates a situation, “where both working time and leisure time are cut into pieces, where the intervals become smaller and smaller, where a growing number of events are squeezed into decreasing time slots.”26 Also of interest in this connection are multitasking phenomena: they force an alternation of consciousness among multiple action contexts per second such that they lead, as it were, to an overlapping of experiences as well as actions. Moreover, as we will see in the next section, there are empirical indications that the shortening and condensation of episodes of experience can lead to a significant transformation of the experience of time and to the perception that it is flowing faster.

In any case, it can hardly be doubted that a growing number of available and potentially interesting goods and pieces of information shortens the span of time that can be devoted to each particular object: if we dedicate a constant proportion of our time budget to reading books, listening to CDs, and answering e-mails, then the average length of time we can devote to each book, CD, or e-mail drops in line with the number of books and CDs we acquire (or borrow) per unit of time or the number of e-mails we receive and send.27 Similarly, the amount of time we can allot to the dutiful perusal of an academic journal decreases in lockstep with the increase in the number of relevant journals: examples of these kinds of compulsions to accelerate can be multiplied at will, and they simply reveal, once again, how much the logics of escalation and acceleration are intertwined in modern society. Because the rates of escalation are higher than the rates of acceleration, a scarcity of time resources and a heightening of the tempo of life occur.

This is driven, moreover, by the fact that the required time for making rational and informed choices and for coordinating and synchronizing actions steadily increases. An escalating quantity of ever more complex goods and services, on the one hand, and the deregulation, flexibilization, and deroutinization of types of action (Handlungspraktiken), on the other, are equally responsible for this. The joint result is that decision-making processes themselves become ever more complex in view of the various options that arise ever more frequently within the course of life and everyday practice and therefore take more time because the consequences of decisions (and their interdependencies) become unforeseeable and force one to expend more and more on the acquisition and processing of information.28 What results for our temporal practice is almost always a feeling of dissatisfaction: in the end, one makes either 1. an at least partially contingent decision on the basis of unsatisfactory information (e.g., “of course it’s possible that another computer model at some other dealer’s would be a better deal, but who wants to invest even more time in finding that out”—Linder views the capability of making suggestion into the functional equivalent of information as the secret mechanism of advertising)29—or 2. one meticulously gathers information and then later has the feeling that one spent way too much time on this one decision or 3. one avoids making a decision and sticks with one’s present computer model, one’s existing health insurance, one’s old-fashioned savings account, etc.30 According to Linder’s analysis, this situation has as an inevitable consequence a diminished quality of individual decisions, i.e., their objective appropriateness; the requirements of temporal rationality force one into an increasing substantive irrationality.31 As I would like to show in chapter 11, collective political decision-making processes find themselves in just the same kind of dilemma, which exerts an immense influence on the ability of society to steer itself and thus on its political self-understanding.

Meanwhile, the temporal deregulation and deinstitutionalization of numerous fields of activity in late modern society has massively heightened the cost of planning and thus the time required to coordinate and synchronize everyday sequences of action. The consequence of the surrender of collective rhythms and time structures is that daily, weekly, and yearly processes are no longer self-evidently prestructured,32 but instead have to be repeatedly planned, negotiated, and agreed upon with cooperation partners all over again.33 If neither sunrise and sunset (as was customary for centuries) nor the factory sirens and no longer even the television sign-off and sign-on can serve as routine initiators of getting up and going to bed, then every individual must plan and reflect and make such decisions for himself. “Today whoever gets out of bed with a good conscience, or is inclined to do so, needs a motive,” remarks the time researcher Karlheinz Geißler.34 The additional burden caused by such (temporally costly) decision and planning processes clarifies one of Arnold Gehlen’s central arguments, namely, that social institutions perform an important burden-easing function in view of the essential openness of action and choice in human existence.35 The contemporary social deinstitutionalization of numerous practices thus leads consistently to an additional (temporal and cognitive) burden, which significantly contributes to the scarcity of time resources and thereby to the heightening of the pace of life.

What is highly interesting with respect to the question of temporal rationality here are the interactions between the new possibilities of technological acceleration and flexible availability and social expectations. In fact, appointments today are themselves becoming increasingly “temporalized” in the sense that they no longer have to be fixed for certain ahead of time, but can be negotiated on the move by e-mail and cell phone (“let’s meet around noon” versus “when I’m ready I’ll call you to see if you’ve arrived”). In his comparative study of European, Japanese, and American patterns of time use, Manfred Garhammer has even derived the general tendency to replace activities with higher levels of time (and social) commitment by those with lower levels of commitment.36 This raises planning costs and the time required for coordination enormously because the number of variables and contingencies proliferates, but it shortens waiting times and avoids temporal rigidities (e.g., the premature breaking off of the previous activity). In view of the ambivalent consequences for one’s time budget, it would be, on the one hand, rational in a higher-order sense to save time and energy by doing without a “mobile” and flexible planning of appointments, but, on the other hand, with respect to concrete individual decisions it can be highly irrational to do so (“what do you mean you can’t call me when you’re ready?!”). In a similar way, it is highly irrational not to keep channel surfing when faced with a boring made-for-TV film; not to check one’s messages all day long (and thus run the risk of missing something important), since e-mail connections take mere seconds; or even to routinely plan entire work days during which colleagues will be unavailable (and thereby create in a certain way a temporary, artifical oasis of deceleration in the sense defined above), something Luhmann proposes as a solution to the problem of the “tyranny of the moment.”37 If the most important conference of the year or the visit of a colleague from another country fell on just such a day, however, even the most convinced defender of this sort of rule would allow for an exception. Yet it is precisely the more undramatic everyday coordination problems that make such a strategy irrational and/or antisocial: “if you don’t send me the attachment tomorrow, I’ll miss my application deadline”; “if you don’t come to our meeting down the corridor tomorrow, I’ll have to make an additional trip to the city again two days from now.” The costs of such macro time-saving strategies are, as a rule, too high for oneself and for others (contrary to most how-to guides on time management)38—unless, that is, one reinstitutionalized them as collectively binding.39

Finally, the technical acceleration of processes simultaneously changes the socially established standards of temporal rationality: to wait seven days for the answer to a letter taking eight days to arrive appears just as appropriate as the same length of time appears inappropriate when answering an e-mail that turns up in its recipient’s mailbox after a few seconds. Technical acceleration does not force a heightening of the pace of life, but it changes the temporal standards that underlie our actions and plans.40

Unfortunately, in the usual time use studies all of these developments are basically not registered (which is why acceleration practically never shows up in the data records that have by now been systematically collected in all the large industrial countries). So whoever hopes to find systematic empirical evidence for such processes of compression and acceleration in the now over-flowing research on time use becomes bitterly disappointed. Time budgeting research in its present form concentrates on the allocation of time among actors and different fields of activity—i.e., on the question who performs what kind of activity for how long—and thereby ascertains the differences between various groups of the population, diachronic developmental trends in the rededication of time resources (where it finds, for instance, that the average time at theater visits has dropped slightly, while, in contrast, time spent in front of the computer has risen; although a bitter dispute regarding the development of the relation between work time and free time prevails),41 and connections between work time behavior and free time behavior,42 etc. However, the acceleration phenomena postulated here cannot be captured by the survey instruments designed for these questions. The total time available always amounts to twenty-four hours a day, so time saved on one activity (e.g., household chores) is spent on another (e.g., watching TV); as a result, one is always dealing with speed-indifferent zero-sum games.43 Whether during work hours one works more and hence faster, during hours spent reading more is read, or in time spent communicating more contacts are made remains uninvestigated. Even the shortening of breaks and idle times, which can be easily ascertained with the help of time diaries, is made invisible partly by the researchers and partly by the respondents in that it is attributed to the substantial fields of activity (e.g., transportation, sleep, or communication). Thus the question whether and to what extent there is an escalation of the episodic density of action and experience per unit of time cannot be answered using the time budget studies published so far.

Consequently, an urgent desideratum for scholarship is the development of innovative research designs that can systematically register the three (or four) diagnosed forms of acceleration: the speeding up of individual actions, the elimination of breaks, the temporal overlapping of activities (multitasking), and the replacement of temporally costly with time-saving activities. A fundamental problem here is the fact that statements about acceleration are relational and therefore can really be tested only by diachronic, iterated surveys (panel studies in particular).

In the absence of such studies, the only possibility that remains is to disclose acceleration processes indirectly by identifying shifts in time budgeting that can be interpreted as the shortening of action episodes. Time spent on personal regeneration (eating, sleeping, body care) offers a particularly good means for this: a shortening here suggests an inference of acceleration in the corresponding processes.

And, in fact, the existing studies are revealing in this respect: the previously justified supposition that the years of the digital and political revolutions around and after 1989 were characterized by a clear surge of acceleration seems to be reflected in the data from the large, countrywide U.S. time use study (the “Americans’ Use of Time Project”) from 1985 (n = 5, 300) and 1995 (n = 1, 200). During this period, in particular with respect to men, the time spent weekly on body care decreased by 2.2 hours, eating by 1.8 hours, and sleeping by a half hour, which suggests that the respondents ate, slept, and washed themselves faster (the data for women are -1.9 for body care, –1.5 for eating, but +1.3 for sleeping).44 This result is confirmed by the European time use data analyzed by Garhammer, from which he likewise derives a clear trend toward a “compression of personal needs” and consequently an acceleration of corresponding activities.45 Especially striking in this context is the finding that the average duration of sleep has fallen around 30 minutes since the 1970s and 2 hours (!) from the previous century.46 Yet just this number makes clear the caution that is necessary when interpreting such results. For, in the first place, the number is contested by other researchers,47 and, in the second place, it would be premature to interpret it as a symptom of a restless, nonstop society: it could also be simply an effect of the fact that heavy physical labor becomes rarer and people become older in postindustrial society and hence the “objective” need for sleep lessens.48

Moreover, the available data strengthen the postulated development in a further respect: the trends toward an increase in multitasking and a growing fragmentation of activities are by now quite uncontroversial.49 Yet precisely this undermines the validity of time use studies: if several activities are performed in parallel within a given time frame (possibly without a clear hierarchization into primary, secondary, and tertiary activities), this poses notorious problems for the attribution of units of time. Even more serious are the consequences of the fragmentation of time and the dedifferentiating dissolution of boundaries between the types, sites, and times of activity: where professional work and household activities or child care as well as free time activities are all done at home, where leisure time activities are coordinated from the workplace, where, say, e-mails regarding matters of private and professional life as well as honorary offices or volunteer work are handled, and corresponding phone calls made, in no particular order, temporal accounting is significantly more difficult. It becomes near impossible where activities no longer permit any unambiguous classification because the spheres of work, family, and leisure time blur together to the point of indistinguishability. A person who listens to Beethoven at work but for this reason discovers the solution to her weightiest professional problem while at the concert hall and arranges her friendships and her free time in such a way that they constantly serve the advancement of her career by fulfilling the ever more important functions of networking just falls through the nets of time budget research.50 It might very well turn out that the survey instruments of time use research are a manifestation of highly temporally differentiated “classical” modernity but are only of rather limited value for analysis of the time structures of late modernity.

In view of the current state of the evidence, then, it is all the more surprising that both the most comprehensive current time budget studies, Robinson and Godbey’s Time for Life: The Surprising Ways Americans Use Their Time and Manfred Garhammer’s How Europeans Use Their Time (Wie Europäer ihre Zeit nutzen), agree that acceleration and temporal compression are the main trends in the development of time use patterns and dedicate great attention to them—without, however, being able to be justify this using their data. Garhammer puts acceleration at the top of his summary list of the ten most important trends in the contemporary development of temporal structures, but, significantly, he refers in support of his diagnosis to, among others, Levine’s study.51 He designates compression, i.e., the shortening and simultaneous performance of activities, as a further main trend, which, according to the definition used here, can likewise serve as an indicator of an acceleration of the pace of life. Conversely, Robinson and Godbey dedicate a chapter to the diagnosis of an unprecedented acceleration of the tempo of life before laying out and discussing their empirical data and spend thirty full pages on the phenomena of temporal compression and time scarcity; nevertheless, they too fail to make any real connection to the time use data that follows.52 On the contrary, their analysis of this data leads them to imply to the reader, against their own diagnosis, that the acceleration of the pace of life is (purely) a fact about subjective perceptions.53 While I have argued that there is a massive and observable “objective” or material basis for the diagnosis of an acceleration of the tempo of life (though it remains to a great extent hidden in time use data), still there can be no doubt about Robinson and Godbey’s conclusion that it is above all the experience of time that has changed as a result of altered practices in everyday life: the quantitative heightening of the objective pace of life seems to lead to a qualitative transformation of the subjective experience of time. This phenomenon, which cannot be explained solely with time budget research and the analysis of empirical evidence for acceleration, now needs to be subjected to a systematic investigation in the following section.

2. SUBJECTIVE PARAMETERS: TIME PRESSURE AND THE EXPERIENCE OF RACING TIME

As the conceptual discussion of social acceleration in chapter 2.1 has shown, the heightening of the pace of life is a paradoxical phenomenon in view of the continual technical acceleration of transportation, communication, and production. Technical acceleration shortens the time bound up in such processes and partially frees considerable time resources such that for a constant quantity of actions and experiences more time is available: thus one would expect a slower pace of action, longer breaks, and less overlapping of actions. For just this reason, the “problem of free time” was understood well into the 1960s not as that of, for instance, free time stress, but rather the “problem” that people (particularly the “uneducated masses,” of course) do not have a clue what to do (rationally) with the “immense reserve capital of freed-up time” (as the Bayerische Gewerbefreund said in an article from 1848 entitled “Excess Steam and Excess Time”)54 that was always imagined as lying in the immediate future. Even in 1964 the cover of Time magazine read, “Americans Now Face a Glut of Leisure—the Task Ahead: How to Take Life Easy.”55

In contrast, a heightening of the pace of life represents a reaction to a scarcity of time resources: for particular actions (or experiences) there is less time available than before. The simultaneous appearance of both forms of acceleration is conceivable only if there are growth processes in which an increase in the quantity of actions exceeds the increase in speeds of performance. Subjectively, i.e., in the way acting subjects experience time, such a scarcity of time resources is expressed in a feeling that time passes more rapidly,56 but above all in the experience of a lack of time and stress and in the feeling that one does not “have” any time (unless the actors had been previously bored).

Now there can be little doubt that just this perception of time has almost continually increased in all Western industrial states since the beginning of corresponding surveys in the 1960s.57 For instance, one gathers from the data reproduced in Robinson and Godbey’s study of the U.S. national time budget surveys that the number of eighteen to sixty-four year olds who indicate they always feel in a hurry or under time pressure rose in stages between 1965 and 1992 from 24 percent to 38 percent, while the number of those who almost never felt under time pressure in the same period fell from 27 percent to 18 percent. In contrast, the number of respondents that indicated they quite often had free time resources (“time on your hands that you don’t know what to do with”) fell by more than half between 1965 and 1994 from 15 percent to 7 percent, while the percentage of those that answered the same question with almost never rose from 48 percent to 61 percent.58 It seems beyond question that the increasing scarcity of time resources is documented in such numbers.

Nevertheless, Robinson and Godbey think they find increasing signs that the feeling of stress and time pressure as symptoms of increasingly scarce time resources has slightly but unmistakably diminished since the mid-1990s and that the numbers signal a trend reversal (the number of those that are always in a hurry dropped from 1992 to 1995 by 6 percent and the percentage of respondents who indicated they have less free time than five years ago dropped by nine points to 45 percent).59 But, contrary to the interpretation of the authors, what is reflected therein is not a slowing down of the pace of life (“The Great American Slowdown”), but rather a subsiding of acceleration: time resources are just becoming scarce less rapidly. The sensation of stress expresses nothing about the absolute tempo of life, but only about its change. Therefore it is not at all surprising, though Robinson and Godbey suppose otherwise,60 that the inhabitants of Russia give relatively high responses concerning the experience of stress and time pressure since 1990 (26 percent of Russian adults indicate, for instance, that they no longer have any time for amusements, compared with “only” 23 percent of Americans), although the pace of life in Russia is presumably still clearly slower than in the U.S.: the rate of acceleration in Russia may be significantly higher in the wake of the transformation after the end of the Soviet Union.

Robinson and Godbey’s data still await confirmation by other studies, particularly from other industrial nations.61 If they prove valid, they could be interpreted as an impressive confirmation of the thesis that around 1990 what is for the time being the last wave of acceleration reached its high point and has been ebbing since.

However, there is another surprising variant of the paradox introduced at the beginning of this section that is reflected in the data of the time use researchers: the dramatic rise in feelings of stress and lack of time between 1965 and 1995 is accompanied by an equally significant increase in free time, which already suggests a growth in free time resources. In time budget research, free time is normally not simply defined as time outside remunerated labor, but rather as the time resources that are not bound up in obligatory activities, and over which one may therefore dispose more or less at will, i.e., as time that remains left over after subtracting work time, family and household time (child raising, grocery shopping, housework), and personal care time (eating, sleeping, body care). This “free time” climbed continually between 1965 and 1995 for practically every population group, even for working women (by 5.6 hours per week in comparison to 10.3 hours for housewives; working men gained almost 6 hours of free time per week). Responsible for those figures are sinking work times and, above all, diminishing housework times that were more than able to offset the growth in paid labor time that has occurred in particular since the 1990s.62 Here is the reason for Robinson and Godbey’s assumption that the heightening of the pace of life might be overwhelmingly a problem of perception.

Even if the reflections of the last section have shown that the heightening of the tempo of life in the sense of a rise in the episodes of action and experience per unit of time can certainly be accompanied without contradiction by a lengthening of free time, it remains to be explained why respondents complain of growing time pressure and of being compelled to accelerate. In view of the data, the pace heightening per se is not astonishing, but the feeling of being rushed is. This is reflected in the finding that the respondents have the impression, in a certain way inversely proportional to the evidence, that their free time is constantly dwindling. Perplexingly, subjectively estimated free time decreases in parallel with the increase of “actual” free time. It not only often amounts to less than half the free time calculated using time journals, but even falls on average under the de facto time spent in front of the television!63 At first glance, the only thing that can be inferred from this with any certainty is that the observed free time is not experienced by actors as a reservoir of free time resources, but rather as a quickly passing quantity of time tied up in actions (and experiences).64

Starting with this paradox, and on the basis of reflections from social psychology and the philosophy of culture, I will try to find an explanation for the transformation of the modern (and a fortiori late modern) experience of time that is reflected in such findings and in doing so to ferret out its internal connection with the escalating density of action and experience.

In the first place, two natural causes for the feeling of time pressure are the fear of missing out and the compulsion to adapt, which have thoroughly distinct roots. The fear of missing (valuable) things and therefore the desire to heighten the pace of life are, as I will show in chapter 7.2, the result of a cultural program that began developing in early modernity and consists in making one’s own life more fulfilled and richer in experience through an accelerated “savoring of worldly options”—i.e., by escalating the rate of experience—and thereby realizing a “good life.” The cultural promise of acceleration lies in this idea. As a result subjects want to live faster.

In contrast, the compulsion to adapt is a consequence of the structural dynamic of late modern societies, more specifically of the acceleration of social change. As I have tried to demonstrate, the more rapid alteration of not just the material structures of the environment but also the patterns of relationship and structures of association, forms of practice and action orientations, unavoidably leads to an existential feeling of standing on slipping slopes, the “slipping slope syndrome.” As a result of the “contraction of the present,” in a dynamic society almost all one’s stock of knowledge and property is constantly threatened with obsolescence. Even in those intervals of time during which a subject has free time resources at her disposal, her surroundings continue to change at a rapid pace. After they have passed, she will have fallen behind the times in many respects and consequently be compelled to catch up: for example, after eight days of vacation a scholar finds an overflowing e-mail account with queries of all kinds, a series of exams to be graded, an impressive number of new publications relevant to his research, new software and hardware offers, etc. It is easy to understand how the feeling of rapidly elapsing time emerges in a highly dynamic society, generating pressure even in periods free of work. The “objective flow of events” transpires more rapidly than the speed at which it can be reactively processed in one’s own action and experience.65 Herein lies modernity’s structural compulsion to accelerate. As a result, subjects must live faster.

To decide whether the fear of missing out or the compulsion to adapt (which, naturally, cannot always be cleanly separated empirically) makes a stronger causal contribution to the acceleration of the pace of life, quantitative or standardized investigations of time allocation are insufficient, as even time use research has recognized by now.66 Instead what can first shed light on this point is an analysis of the motives for respective (free time) activities and shifts in allocation.

Of course one must keep in mind here that time pressure has a positive connotation in the patterns of modern social recognition: not to have any time signals desirability and productivity. Time scarcity is therefore without doubt a communicatively strengthened, if not produced, phenomenon. However, it is entirely conceivable that the tempo-related pattern of distinction in the concept should be flipped around: if faster previously meant better because it signaled higher competencies and resources and thus an evolutionary and social advantage, then in late modern society slowness may definitely become a marker of distinction: whoever manages to leave oneself time, controls one’s own availability, and enjoys free time resources has the advantage.

In any case, in the absence of systematic surveys on the matter, when it comes to explaining or justifying its allocation, the degree to which a vocabulary of must and obligation dominates the social semantics of free time is remarkable. In glaring contradiction to the prevailing ideology of individual freedom and the minimally restrictive ethical code of modern society, and in a way that cannot be explained simply by the social attractiveness of time scarcity, social actors surprisingly speak continually of their activities as obligatory: “I really have to read the newspaper again”; “I ought to finally do something for my fitness, buy new clothes, learn a foreign language, pay attention to my hobbies, meet up with my friends again, yes, go to the theater, take a vacation, etc.”67 It would hardly be surprising if this “must” semantics dominated nonproductive activities more strongly in Western societies than in any highly normatively regulated traditional society. It seems to be a natural reaction to the situation of living on slipping slopes: “we dance faster and faster just to stay in place”; it is becoming more and more difficult to stay up to date. “Daily life has become a sea of drowning demands, and there is no shore in sight,” finds Kenneth Gergen, while Robinson and Godbey and the leisure time researcher Opaschowski agree in noting that there seems to be an exponential multiplication of the necessary and indispensable even in free time.68 Moreover, insofar as the slopes become steeper, i.e., the rates of change increase, an inherent tendency toward a gradual shift in motives seems to develop: the rhetoric of the promise of acceleration is increasingly replaced on the individual and political level by that of the compulsion to adapt. In place of an orientation toward long-term goals there appears an effort to remain open to options and opportunities in a world characterized by change, contingency, and uncertainty.69

This suggests a speculative conjecture for which there are in any case several sources of empirical support: behind the striving to keep pace with change, and its resulting demands, and the attempt if not to increase the number of available options, which Heinz von Foerster calls the ethical categorical imperative of modernity,70 then at least to maintain them in the face of the growing imponderability of both the world and one’s own needs, activities that are held to be valuable or choiceworthy for their own sake disappear from view. No time is left over for “genuinely” valuable activities. This is at least as true of work as it is of free time. Everywhere it seems like there is no time available for long-term goals—in the example of the scholar, for instance, writing her new book—because of the constant pressure of little demands in the meantime, things which are very often directly related to keeping open opportunities. In support of this claim, which may at first glance appear unfounded, one can, first, identify a consequential principle of social functioning and, second, present some striking survey data.

Sequencing represents an almost natural means of weighting and ordering activities in accordance with their value.71 Do the most important or valuable thing first, then the second most important, etc., and the less important things will get done if afterward there are still time resources available. In a functionally differentiated society with widely linked interaction chains, however, this ordering principle is replaced more and more by deadlines and appointments for coordinating and synchronizing action. In view of this prevailing orientational primacy of time, Luhmann states that “it seems as though the division of time has confounded the order of values.”72 “The power of the deadline” now determines the serial order of activities and, under conditions of scarce time resources, brings it about that goals that are not bound to deadlines or appointments are lost from view because the burden of what “has to get done (before)” smothers them, as it were—they leave behind only a vague feeling that one doesn’t have time to do “anything” anymore. We are constantly “putting out the fires” that flare up again and again in the wake of the many-layered coordination imperatives of our activities and no longer get around to making, let alone pursuing, long-term objectives.73 As Luhmann further observes, “the division of time and value judgments can no longer be separated [in the traditional way—H. R.]. The priority of deadlines flips over into a primacy of deadlines, into an evaluative choiceworthiness that is not in line with the rest of the values that one otherwise professes.”74 He thereby makes clear that a kind of duplication of the order of values occurs in light of these temporal structures. We “profess” the higher worth of certain activities or even ways of life (e.g., walking on the beach, going to the theater, civic engagement, playing the violin, writing a novel), although this “discursive” order of values is hardly reflected in the order of preferences expressed in our actual activities.

And just this has been confirmed by empirical surveys that connect time use data with questions of the quality of life. According to them, actors spend their time by and large on activities that they not only hold to be of little value, but that, according to their own reports (among others those recorded in time journals), also give them little satisfaction. This holds true in particular for watching TV: respondents not only value it least among all free time activities but also draw even less satisfaction from it than from work.75 In a countrywide American survey, on a scale of satisfaction running from 1 to 10, TV received an average score of 4.8, in contrast to work at 7.0 (in 1975 even 8.0) or shopping (6.4 in the 1985 survey); in 1995 the female respondents at least actually drew more satisfaction from cleaning work around the house (5.6!) than from time spent in front of the TV, while men said they got more enjoyment from cooking (5.5) than from TV.76 Yet inhabitants of Western industrial states devote on average almost 40 percent of their free time to just this activity: more than two hours a day and much more than any other free time activity. In contrast, only minimal (and in the years since 1965 tendentially decreasing) time resources are allocated to many activities that actors hold to be integral components of a “good life” and that in fact produce feelings of great satisfaction in them.77 “In other words, the allocation of free time to such ‘worthwhile’ leisure activities as reading serious literature, engaging in community activities, or attending cultural events is a blip on the free-time radar screen,” as Robinson and Godbey summarize their results and state an unmistakable disparity between what the actors say they like to do and what they actually do in spite of this.78

At first glance, though, this finding is, in one respect, strikingly opposed to the line of argument developed so far: the fact that the respondents can spend so much time on watching television, an activity that they themselves see as of little worth, seems incompatible with the thought that it is the urgency of the fixed term and time scarcity that hinder them in the pursuit of more satisfying activities. Yet a closer look reveals that this finding does not absolutely contradict that thesis, but may rather even lend it support. For, first, it is incontestable that TV is one of the few activities that can always be used to fill up short fragments of time and bridge gaps (i.e., breaks): it requires neither buildup nor follow-up. Quite logically, the studies also demonstrate that TV consumption during holidays, when free time resources are less fragmented, markedly declines (while the activities held to be more valuable come into their own), although free time resources increase.79 Second, however, TV also requires only a minimal expenditure of psychological and physical energy. Leaving aside sleeping and dozing, no other activity calls for such comparatively low operative “input,” which is why TV consumption is also generally seen as an especially “passive activity.”80 For this reason it seems (misleadingly) particularly well-suited to serve as an “activity” that can compensate for stressful everyday experiences under intense time pressure.81 This corresponds to the observation of a “polarization” of everyday time into phases that are characterized as stressful, burdensome, and very demanding and complementary compensating times that are characterized by passivity.82 Nietzsche already diagnosed this tendency of modern life to place subjects under stress and time pressure in such a way that when they at last have time for themselves what they want is “not only to let themselves go, but to stretch out at length as ungainly as they happen to be” (or even what Nietzsche couldn’t yet do: watch TV).83

But, third, TV consumption thus represents one of those activities, so characteristic of late modern entertainment culture, in which the “input-output” relation is especially positive regarding immediate satisfaction: the TV promises “instant gratification” without previous expenditure of time and energy, an inestimable advantage in a society marked by high rates of change and oriented to short-run time horizons. Now one further factor is important for understanding the psychological attractions of TV (and other entertainment media designed for passive consumption): research subjects generally report distinctly higher satisfaction values during the activity of watching TV than after, and as a rule they experience viewing more positively than they judge it to be from a more distanced perspective with respect to a scale of activities held to be satisfying or worthwhile. The short-term experiential gain of TV is thus relatively high, though the “enduring” value is not: this is shown not merely “subjectively” in the low valuation of TV consumption in questionnaires but also in psychophysical investigations of mood, degree of contentment, and capacities of concentration and attention after the end of the activity; TV apparently tends to leave behind tired, hardly recuperated spectators who are in a bad mood.84 In fact, the creeping “restructuring of the order of values by time problems” indicated by Luhmann might take place in cultural life in the following way: since the social structure rewards short-run orientations because of high rates of instability and change, and the entertainment industry opens up any number of literally “attractive” experiential possibilities that offer “instant gratification” with a favorable input-output relation, less and less time resources are expended for those activities held to be more valuable and satisfying on a cognitive, abstract level that require large or long-run investments of time and energy.85 One may consider opera to be more valuable than a musical, but nevertheless go to the latter; judge a good restaurant to be more satisfying than McDonald’s and still stop at the fast food chain; ascribe much value to playing the violin, but instead of that try out the latest CD releases at the cultural entertainment store; have experienced engagement with poetry as extraordinarily satisfying and still turn on the TV in its place; hold the writing of a novel to be the most worthwhile activity of all, but wind up playing a computer game while looking for the corresponding file; indeed, we might even be absolutely certain that we would get more from a demanding film classic than from a Hollywood action comedy and nevertheless buy tickets for the latter.

Thus in the long run the activities originally held to be worthwhile get forgotten and devalued: “tasks that are always at a disadvantage must in the end be devalued and ranked as less important in order to reconcile fate and meaning. Thus a restructuring of the order of values can result simply from time problems.”86

Reflections of this kind naturally have an undertone of cultural criticism, but they are in accord with the finding that what actors hold to be valuable and experience as satisfying and what they do significantly diverge in Western industrial states. And anyone who wants to defend a diagnosis of cultural decline would do well, in my opinion, to give central place to an analysis of the dimension of time.

However, the indicated revision of the social order of values would be an unreflective and unintended consequence of temporal-structural social developments. A democratically constituted political community that wanted to hold fast to the idea of collective autonomy in the face of social processes that are taking on a life of their own (sich verselbständigende) could definitely come to the conclusion that it must counteract this politically. But it would have to resort to thoroughly ambivalent methods of binding itself in a deliberative democratic but, as it were, “auto-paternalistic” fashion in order to hinder the erosion of cultural practices that it views as valuable (and that need long-run investments of time) by an uncontrolled “market paternalism” that favors short-run realities.87 Younger generations will involve themselves with (and hence experience the value of) practices that unfold over the long run and require large prior investments only if they are encouraged to do so by stable trust relationships and reliable role models. Moreover, trust relationships of this sort only develop in the long run. Therefore, what would be culturally required is, as it were, the establishment of “oases of deceleration” protected by the state, within which the corresponding experiences could be had.88 However, the chances of such an intervention depend decisively on the structural presuppositions of a political steering of societal development. Yet these are noticeably worsening in contemporary society as a result of the acceleration-induced desynchronization of functional spheres, as I would like to demonstrate in part 4.

In any event, one can derive from these considerations an illuminating explanation for the widespread feeling of urgent time scarcity despite greater time resources: on account of the offerings (which function literally as psychophysical “attractors”) of ample experiences with better input-output ratios and an immediate satisfaction of needs, there remains in late modern society no time for things that are held to be “really important”; we literally never get to (do) them anymore, even though we may console ourselves with the thought that we will at last take the time to do them some other time. For the time being we orient ourselves to the urgency of the fixed term—regardless of how great our free time resources may be. Thus, in a countrywide American study of participation in the arts from 1993, the majority of respondents indicated that their reason for staying away from cultural events and museums was that they “had no time” (this answer was four times more common than lack of money), even though, in agreement with the “more-more pattern,” it was (even after controlling for education and income) precisely the people with the fewest uncommitted time resources (or the greatest number of work hours) who participated most frequently.89 Nevertheless, that answer need not simply be a cheap excuse. Astonishingly, the feeling of time scarcity sets in whenever we take into consideration only the activities named first in each of the examples in the list given four paragraphs earlier but not the second, with which we spend far more time.

Moreover, Kubey and Csikszentmihalyi explain the differences in the long-run satisfaction values using the concept of flow. According to this idea, the most intensive (and enduring) feelings of happiness occur in the performance of activities that are done for their own sake, unencumbered by difficult circumstances, in which abilities and challenges are balanced at a high level: if we are not challenged, i.e., abilities clearly exceed the challenges, then boredom threatens; if, in contrast, we are overly challenged, we react with stress and anxiety. The higher the balanced level, the greater the chances of an experience of flow. Tennis or playing the violin, writing a novel, running a boarding school, or even learning to understand a complicated piece of twelve-tone music are good candidates for this. They all presuppose long-term investments and the readiness to delay gratification.90

One can certainly suppose that an elitist, culture-critical bias lies behind these reflections even if they are supported by empirical evidence. Nevertheless they have a highly interesting and until now unnoticed correlate in the paradoxes of temporal experience that may prove to be fruitful for the explanation of the sense of “racing time.”

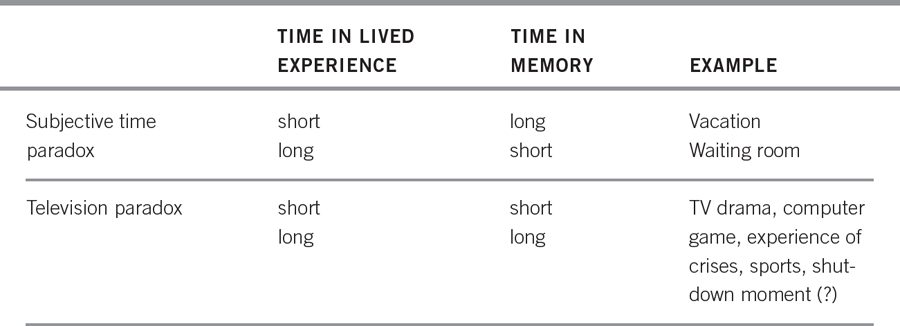

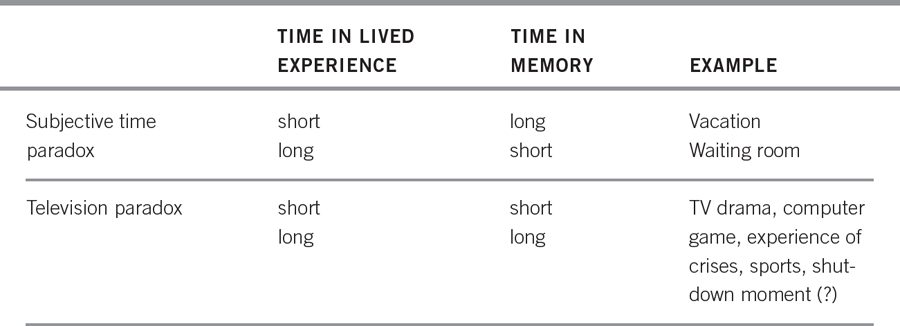

As Hans Castorp remarks in Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain and William James tries to justify psychologically, experienced time has the peculiar property of in a certain way “inverting” itself in memory when compared with lived experience: “In general, a time filled with varied and interesting experiences, seems short in passing, but long as we look back. On the other hand, a tract of time empty of experiences seems long in passing, but in retrospect short.”91 The experience of time thus yields either a short-long pattern (short experiential time, long remembered time) or a long-short pattern (long experiential, short remembered time). As a so-called subjective paradox of time, this phenomenon is well-documented and also entirely explicable: episodes of lived experience that are felt to be interesting leave behind more pronounced traces in memory than the boring ones, and their larger memory content operates as an extension of the remembered time and vice versa.92

On the other hand, a second phenomenon that runs contrary to this pattern has hardly been studied. I will call it, following Ariane Barth, the television paradox.93 Time spent in front of the TV (for instance, watching a crime drama) displays all of the features of short experiential time (high stimulus density, emotional involvement—when the killer arrives or the shooter begins his penalty kick approach, one’s heartbeat, blood pressure, and galvanic skin response change—and the feeling that time is “flying”),94 but as soon as the TV is turned off, and especially later in memory, it behaves like long experiential time: it “leaves nothing behind.” The remembered time rapidly shrinks, which is why test subjects often report a “great void” after the end of TV consumption that is surprising in light of the high density of experience. This may be in large measure responsible for the bad “mood values” after this activity. Kubey and Csikszentmihalyi quote for instance an English teacher who summarizes his experience as follows: “I find television almost irresistible. When the set is on, I cannot ignore it. I cannot turn it off. I feel sapped, will-less, enervated. . . . So I sit there for hours and hours. . . . I remember when we first got the set I’d watch it for hours and hours, whenever I could, and I remember that feeling of tiredness and anxiety that always followed those orgies, a sense of time terribly wasted. It was like eating cotton candy; television promised so much richness, I couldn’t wait for it, and then it just evaporated into air. I remember feeling terribly drained after watching for a long time.”95

Thus TV watching apparently tends to produce a short-short pattern that is novel and paradoxical relative to the “traditional” experiences of time, which is not to say that it always does: under certain conditions, to which I will return shortly, it can doubtless produce “normal” patterns of temporal experience. Unfortunately, methodologically rigorous empirical investigation of this TV effect remains for the time being an unfulfilled desideratum.96

However, presumably television is not the only activity that generates a short-short pattern. Computer games, for instance, seem even more relevant to the production of these patterns: they seduce players into occasionally hours-long feverish activity, with high stimulus density and a high degree of involvement, but at the point of departure (in particular, when one stops before reaching the goal of the game) an overpowering feeling of the “shrinkage” of time sets in. Interestingly, the “shut-down second,” i.e., the short time the computer needs to end the program, is often felt to be unbearably long and extraordinarily torturous; perhaps because in it the “shrivelling up of time” is quite clearly experienced. So this short period may even behave in accordance with a long-long pattern where the flow of time seems to slow down, one that is otherwise well-documented as a mode of temporal experience in extreme situations or in decisive moments in sports.97 Successful athletes supposedly possess the ability to perceive fast athletic happenings, as it were, in “slow motion” and therefore dispose over sufficient time to react. Presumably this experience of time is also unaltered in memory (table 5.1).

The question what time pattern a visit to the cinema leaves behind is instructive here. It seems that contextual conditions and the subjective meaning the film has for the moviegoer exert a decisive influence. This might actually also give us a crucial clue to an explanation of the television paradox: my conjecture is that in the case of television (and computer games) memory traces are erased so quickly because the experience is, first, desensualized and, second, as a rule decontextualized. Desensualization means here that it is exclusively sight and hearing that are addressed, while tactile sensations, smells (which are, as is well-known, of great significance for long-term memories), and tastes are absent. In addition, all stimuli come from a narrow, spatially limited “window.” Relevant studies have shown that the degree of neural activation and brain functioning is, when compared to other activities, altered or limited.98 Nevertheless it seems to me that the phenomenon of decontextualization is of even greater importance here: what happens on the screen does not stand in any relation to the rest of our experiences, moods, needs, desires, etc., and does not react to them; it is, in the narrative context of our life, almost completely “contextless” or unsituated and therefore cannot be transformed into the experiential constituents of our own identity and life history. They are stories of strangers without any internal connection to what we are doing before or afterward or what we believe ourselves to be, so “nothing remains behind.” Things are different when, in contrast, such connections can be made: for instance, to Star Wars fans who live with and through their heroes, collect the memorabilia, read magazines, etc., watching the newest episode is not contextless. It can be narratively assimilated into the horizon of their life and identity with ease. So it stands to reason that in such cases the television or cinema experience follows the short-long pattern.

TABLE 5.1 Paradoxes in the Experience of Time

Moreover, the short-short pattern could prove to be very instructive regarding the (late) modern experience of “racing time.” It is conceivable that everyday experience in contemporary society increasingly produces this temporal pattern because the episodes of experience that densely follow one another display a tendency toward decontextualization: lived experiences that are short, stimulation-rich, but remain isolated from each other, i.e., without any internal connection, and replace each other in rapid transitions such that time begins to race in a certain way “at both ends,” that is, it elapses very fast during the activities, which are felt to be brief (and often stressful), but at the same time it seems in hindsight to “shrink” so that days and years hurry by as if in flight. In the end we have the feeling that we have hardly lived, although we may be old in years. Thus we lived, so to speak longer (objectively), and shorter (subjectively) at the same time.99 Objective evidence that in contemporary society time in fact seems in retrospect to have gone by faster than expected is provided by an empirical study of Michael Flaherty with 366 experimental subjects from three age groups that were supposed to indicate how fast last year had gone for them on a five-point scale from 1 (very slow) to 5 (very fast).100 The average answer turned out to have a value of 4.216, thus between fast and very fast!101

One cause for the assumed decontextualization of episodes of action and experience might lie in the already discussed progressive destructuring of everyday life and the related permanent availability of other possibilities of action and experience. When ginger bread cakes, strawberries, and the possibility of going swimming are available 365 days of the year, they become detached from specific spatial, temporal, and social contexts and make a linkage of the experience bound up with them to further experiences and memories impossible or improbable.102 In any case, this destructuring and decontextualization is making the centuries old (Judeo-Christian) proverb that there is “a (specific) time for everything” (and, one could add, a fixed place) increasingly obsolete: many things are becoming permanently available and almost arbitrarily combinable with other things.

In this context the cultural and historical-philosophical reflections of Walter Benjamin seem to be extraordinarily clear-eyed and far-seeing. He lays out the reasons why the incongruence of the space of experience and the horizon of expectations, on the one hand, and the accelerating succession and stringing together of noncumulative, isolated episodes of experience, on the other, lastingly alter the structure of subjective (temporal) experience.103

Benjamin diagnoses an advancing loss of experience (Erfahrungsverlust) in modern society that results from the inability of subjects to transform the variety of abrupt lived events (Erlebnisse) in everyday life (which was paradigmatically embodied for him as for Simmel in metropolitan life) into genuine experience (Erfahrung).104 Experience is for Benjamin ineradicably linked to the embedding of what has been lived in an experienced history and a lived tradition. It emerges in an “appropriation” of what has been lived with the help of stable, narrative patterns anchored in memory and in the light of historically established, antecedent horizons of experience. So lived events can become experiences only if they can be placed in a meaningful relationship to an individual and collective past and future. As one can derive from this, genuine experiences enter into the identity of a person, his or her life history; memory traces of them are largely resistant to erosion. However, they become impossible in a world of permanently changing horizons of expectation and continuously reconstructed spaces of experience.105 Therefore, the shorter the period of time in which the space of experience and the horizon of expectation are congruent (the present), and the greater the number of lived events per unit of time, the more improbable the transformation of lived events into experiences becomes.106 Modern time is thus for Benjamin the time of players, devoid of experience and strung together as a chain of noncumulative, disconnected, and abrupt lived events from which no experiences result, but which subjects later try to recall with the help of “souvenirs” (also in the form of photos).107 The activities of watching TV and playing computer games could be taken as paradigmatic for such a succession of isolated lived events: their nontranslatability into experience makes them remain mere episodes and thereby accelerates the erosion of the memory traces connected to them.

As these considerations show, the society characterized by the short-short pattern is a society rich in lived events but devoid of experience. Time slips through its hands like water at both ends—in living it and in remembering it. Thus one may conclude from the television paradox that, from the perspective of the subjective experience of time, the flow of time itself indeed accelerates for social-structural reasons.

3. TEMPORAL STRUCTURES AND SELF-RELATIONS

As part 2 has already shown, the processes of technical acceleration equally affect the relationships of subjects to space and time and to people and things, while the acceleration of the pace of life alters their action and experience by heightening the number of actions and lived events per unit of time. From this it necessarily follows that the modern acceleration dynamic not only transforms the way subjects do things but also the way they are, i.e., their identities or the way they relate to themselves, because these are constituted by those relationships and actions. Our sense of who we are is really a function of our relationship to space, to time, to our fellow human beings and the objects of our environment, and to our action and experience, and vice versa our identity is reflected in our actions and relationships: the two sides are thus interdependent.108 In sociology the claim that social structure and the structures of the self are correlated with one another, so that, for instance, there must necessarily be some correspondence between societal modernization processes and the construction of subjective relations to self, is practically a truism.109 As I stated in the introduction, my thesis is that temporal structures (of society and of subjects) are the precise link between the two sides and, as it were, guarantee their “structural coupling.” So in this section it is now time to pursue the question concerning the ways in which transformed time structures find expression in modern and late modern forms of identity. Is there such a thing as a dynamization or acceleration of identity, of the relationship we have to ourselves, of our way of being (Seinsweise)?

To answer this question one should keep in mind that self-relations have an indissolubly temporal structure in which the past, present, and future of a subject are connected.110 Who one is is always also defined by how one became it, what one was and could have been, and what one will be and wants to be. In every identity-constituting, narratively constructed life history it is not only the case that the past is reconstructed; at one and the same time the present is interpreted and a possible future is projected. Therefore, self-relations are always also relations to time, and they can exhibit large, culture-dependent variations. In some cultural milieus identity seems to be primarily developed through an orientation to the past and to traditions (and the obligations and status definitions derived from one’s ancestry), while in other cultures meaning is shaped for the self by expectations and plans for the future (as a time to be consciously created or one that will be fulfilled like a destiny). By contrast, in a society where the past has lost its obligating power, while the future is conceived as unforeseeable and uncontrollable, “situational” or present-oriented patterns of identity dominate.111 At the same time, in subjects’ “daily identity work”, several time horizons of differing scopes are constantly interwoven: the patterns of time and identity of the respective situation, of the given form of everyday practice, of the overarching perspective on one’s own life as a whole, and, finally, of the historical epoch must continually be brought into accord with each other.112 Transformations in society’s temporal structures and horizons therefore exert an inescapable influence on the temporal structures of identity formation and maintenance. Furthermore, according to the thesis I develop in chapter 10, it is here more than anywhere else that one can discern a break between classical modernity and what one may label late or (depending on one’s viewpoint) post modernity.

The diagnosed quickening of social change to an intra generational tempo and the accompanying escalation of contingency and instability are of fundamental importance for the transformation of the temporal structure of identities as a result of social acceleration. This is responsible for the fact noted by Lyotard, namely, that in “postmodernity” all identity-constituting relationships and statuses require a temporal marker: if families, occupations, residences, political and religious convictions and practices can in principle be changed or switched at any time, then one no longer is a baker, husband of X, New Yorker, conservative, and Catholic per se. Rather one is so for periods of an only vaguely foreseeable duration; one is all these things “for the moment,” i.e., in a present that tends to shrink; one was something else and (possibly) will be someone else.113 Social change is thereby shifted, as it were, into the identity of subjects. Of interest here are the questions whether those relationships can still in general define our identity and whether we disregard identity predicates in our self-description because they suggest a stability that cannot be made good: it is not that one is a baker, rather one works as one (for two years now); not that one is the husband of X, rather one lives with X; not that one is a New Yorker and conservative, rather one lives in New York (for the next few years) and votes for conservatives.114

In the end such a perspective leads to the thesis of a shrinkage of identity. The self collapses into an, as it were, predicateless “punctual self” that no longer identifies (without remainder) with its roles and relationships but instead takes on a more or less instrumental attitude toward them.115

More commonly, in identity research the observed change (whose magnitude and scope are, of course, heavily contested, though the developmental tendency cannot be doubted)116 is interpreted as a dynamization of identity or the self: subjects are still defined by their roles, relationships, and convictions and acquire their self-understanding in and through them—they are still bakers, husbands, and Catholics—but the (substantial) identities that rest on these (including preferences and evaluative beliefs) are becoming temporally unstable. They tend to change from situation to situation and from context to context.117 In chapter 10 I will show that these two diagnoses are not necessarily incompatible. They simply concern, as it were, the two distinct sides of the process of self-determination that can be expressed by “I determine myself.” The subject side in this process (the who of identity) shrinks to a predicateless point, while the object side (the what) appears situationally fluid.118

The concept of a stable personal identity may thus prove to be a natural correlate of a type of social change whose pace is synchronized with the change of generations and hence a constitutive sign of classical modernity. In traditional societies with lower rates of change, individuals find themselves defined by antecedent, enduring structures and thus, in a certain way, by intergenerational identities, whereas stable, long-term individual identities cannot withstand the fast pace of change in late modern society and become, so to speak, broken up, such that intragenerational (or even intrapersonal) identity sequences arise. A highly dynamic society like that of late modernity therefore compels a corresponding dynamic in individuals’ self-relations and patterns of identity by awarding flexibility and a willingness to change in contrast to inertia and continuity: subjects must either conceive themselves from the very beginning as open, flexible and eager to change or run the danger of suffering permanent frustration when their projected identities are threatened with failure by a quickly changing environment.

I will attempt to give a more detailed account of the kind of “situational” identity that results from this in part 4, which deals with the consequences of social acceleration. However, as a provisional finding one can state that the acceleration of the pace of life does in fact seem to imply something like a sequencing and dynamization of forms of existence: there is an acceleration not only of what individuals do and experience but also of what they are.