ACCELERATION AND RIGIDITY: AN ATTEMPT TO REDEFINE MODERNITY

IN A WRITTEN SURVEY IN North Thuringia, in 2002, a seventeen-year-old student answered the question “In your view, what are the main problems of youth today?” by checking off two bullet points: “no hope for the future” and “a rigid and at the same time hectic society in which everyone only thinks about themselves and it is difficult to find a place for oneself without help.”1 In this succinct, everyday diagnosis of the problem, one sees the basic temporal-structural difficulties of late modernity worked out in the previous chapters bundled together with astonishing precision: on the one hand, the action-orienting capacity of future horizons and the meaning-constituting unity of past, present, and future become problematic (under pressure from autonomized systemic necessities), and, on the other, there is a simultaneous perception of higher rates of change and rigidity beneath the surface.

Now one may with good reason wonder just how much these represent time problems that are really specific to our epoch. Doesn’t the two-sided fear of both change and stasis reflect the ineradicable duality of Herclitus’s παντα ρει (every thing is in flux) and Parmenides’ εν χαι παν (permanent, unchanging being), which presents itself as an invariant given in the world? For instance, Georg Simmel finds that “if we consider the substance of the world, then we easily end up in the idea of . . . an unchangeable being, that suggests, through the exclusion of any increase or decrease in things, the character of absolute constancy. If, on the other hand, we concentrate upon the formation of this substance, then constancy is completely transcended; one form is incessantly transformed into another and the world takes on the aspect of a perpetuum mobile. This is the cosmologically, and often metaphysically interpreted, dual aspect of being.”2

If one views the world from these two extreme perspectives, however, the horizon of the future almost inevitably becomes cloudy: as Pausanias had already complained in the second century before Christ, the future—set in motion by “demonic powers”—appears either as highly transitory and uncertain or as the result of an inalterable, eternal fate.3 But whether such a perspective is taken depends not least on the chances that an individual (or collectivity) has of shaping its own existence, and these are themselves conditioned by education and material well-being. This argument can be strengthened in light of the findings of current research.4

In contrast to such ontologizing or at least anthropologizing interpretations of the experience of time and the future, I have tried to consistently adopt a perspective oriented toward cultural and social history. This has delivered conclusive evidence that a given epoch’s image of history and the temporal life perspectives of its participants are highly dependent on the social and cultural speed of change endogenous to society and that this speed of change continually increases as modernity unfolds. The time perspectives attributed to Heraclitus and Parmenides gain their plausibility from a philosophically distanced view wherein history and the world appear to be a static space of changes or, in other words, a stable space in which various histories transpire. Yet in the Christian worldview this space of histories was already overlaid by the dimension of “salvation history,” the linear time of which spans from the creation through the birth of Christ to its ending with his return.5 This does not at first alter the experience of worldly time much; it remains a space for exogenously produced, uncontrollable vicissitudes of life, although movement and inertia now appear in the paradigmatic form of an opposition between the worldly/temporal and the transcendent/eternal.6

Then in the wake of an increasingly dynamic modernity a direction of movement and a developmental perspective enter into the worldly or secular space of history. This leads to a different experience of historicity and the time of life, one in which movement and inertia no longer form the supratemporal, ahistorical frame of life and history, but where dynamization becomes a basic element of society and history in such a way that the relationship between the two principles appears from then on as historically asymmetrical and the continual displacement of the balance between them can become the characteristic experience of modernity. Quite surprisingly, though, at this point a countertendency to the historical tendency of acceleration or dynamization makes its appearance, namely, an inclination toward structural and cultural rigidity that manifests itself ever more strongly during the advance of modernity. As I have shown, this principle must be understood as a paradoxical complement of modern acceleration.

In the concepts of acceleration and rigidification, which characterize the modern experience of time, the timeless principles of movement and inertia thus themselves appear to be dynamized once again. Thus the “hectic” and “rigid” qualities spoken of in the quotation at the beginning of this chapter cannot be simply reduced to those supratemporal basic principles. They are rather expressions of a dynamized experience of time that belongs to a specific epoch. That these two tendencies are beginning to be radicalized in recent times at the cost of the future horizon that characterized classical modernity (something also apparent in the quotation) points to a new transformation of an epoch-specific experience of time and the world. As we have already seen, this change can only be coherently conceived from an acceleration-theoretical perspective as both a break and a continuation of modernity. For the history of modernity can not only be plausibly reconstructed as a history of acceleration; this is in fact the only way in which the unity of its driving forces, its contradictions, and its historical phases can be revealed. Therefore, it is now time to return to the question raised in chapter 1 regarding the status of the principle of acceleration in the context of the driving forces of modernity as they have been traditionally identified by sociology. In doing so, we will provide sharper contours for the epoch-specific breaks and continuities discussed here in part 4 and thereby deepen them into a diagnosis of the times.

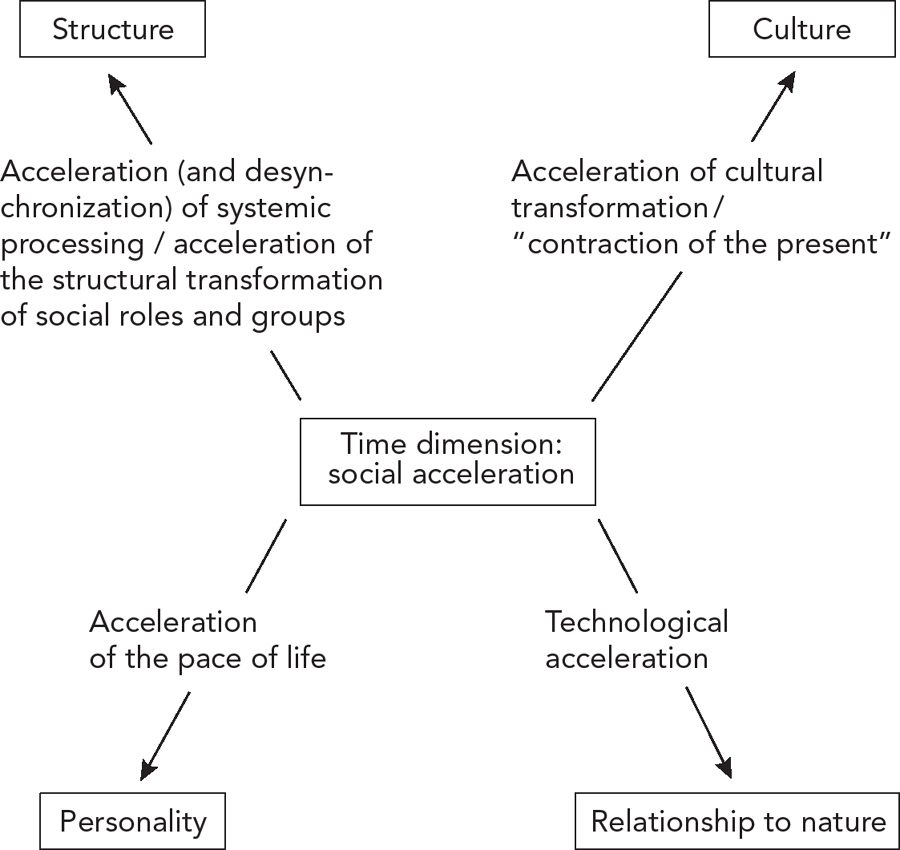

In chapter 1.2.b, I argued in connection with the work of Hans van der Loo and Willem van Reijen that analyses of social formations and their transformations usually begin from a perspective that is focused on either structure, culture, the dominant personality type, or, lastly, on the relationship to nature. Analyses of modernity are thus developed that tend to be, in accordance with the perspective chosen, structuralist, culturalist, subject-centered, or materialist. It turned out, however, that the corresponding definitions of modernization as a process of differentiation, rationalization, individualization, or domestication each leave out the specifically temporal dimension of the development of modernity that so undeniably constitutes a basic experience of the modern era. One of the main aims of this book has been to fill in this lacuna. The course of its argument has entirely confirmed the thesis formulated in chapter 1, namely, that acceleration is of constitutive significance for each of the four dimensions of development (cf. figure 12.1). While it is, of course, true that not all regions and segments of the population of the modern world are caught up in the transformative dynamic of social acceleration to the same degree, it is nevertheless the logic of acceleration that determines the structural and cultural evolution of modern society.

If one attempts to transfer the results of this investigation into the schema of modernization developed in chapter 1.2.b, the following picture emerges. To begin with, it is undoubtedly the case that technical acceleration is of fundamental importance with respect to the relationship of society to nature and that it is closely interwoven with the process of the domestication and domination of nature. The acceleration of transportation, communication, and production implies the enhancement of natural processes themselves (consider, for instance, the agricultural revolution) and the overcoming of natural limits, and hence at the same time an acceleration of processes of exchange with nature.

Moreover, the progressive acceleration of the pace of life has weighty consequences for developments in the dominant forms of identity and personality. As has been shown, the concepts of individualization and the dynamization of perspectives on life correlate to each other in many domains.

Finally, the acceleration of social change is intrinsically linked just as much with the structural as with the cultural transformation of society. In fact, structural and cultural changes (as one can see in the concept of rationalization, for instance) are not only empirically but also analytically so tightly bound up with each other that from the very start they could both be subjected together to a specifically temporal analysis under the wider concept of the acceleration of social change. With respect to the social-structural side of modernization, two analytically separable but interconnected aspects appeared. If one sees functional differentiation as the decisive structural feature of modern societies, then, as the inquiry in chapter 7.3 revealed, there can hardly be any doubt that while it may be interpreted as an adaptive reaction to the pressure to accelerate, it also generates in turn an immense heightening and accelerating effect as a result of the temporalization of complexity. Therefore, the acceleration of systemic processing in differentiated subregions (i.e., the acceleration of financial transactions, artistic and economic production, scientific discoveries, technical developments, etc.) through the externalization of all points of view irrelevant to the given system is an ineradicable tendency of the process of functional differentiation. In contrast, if one starts from the assumption that the basic structure of society is defined now as ever by the fabric of social associations, groups, and role patterns that ensures the production and reproduction of society, then it is undeniable that modernization implies an acceleration of structural change insofar as it increases the speed of change in familial and employment structures and causes associations and milieus to tend to become short-lived and volatile.7 This makes it increasingly difficult to identify associational structures that are socially and politically significant. Both structural developments are accompanied by potentially problematic side effects: in the course of the argument, we have seen that the process just mentioned produces the danger of social disintegration, while functional differentiation, due to the fact that the respective subsystems can be accelerated to different extents, leads to the problem of desynchronization.

From a cultural perspective the most wide-ranging consequence of social acceleration proves to be what I have described, following Hermann Lübbe, as the contraction of the present, i.e., the progressive shortening of the periods of time for which one can count on stable stocks of knowledge, action orientations, and forms of practice. It leads in the first place to a divergence of the space of experience and the horizon of expectation and thus to a temporalization of history (and life) that is then taken back again in late modernity in favor of a highly dynamic contemporization. This was the thesis developed in the previous chapters. The acceleration of cultural change in the form of comparatively faster and easier changes in lifestyles, fashions, leisure time practices, stocks of knowledge, familial, spatial, political, and religious bonds and orientations thus constitutes one of the main traits of cultural modernization.8 It also harbors far-reaching consequences for the political self-understanding of modernity and for the culturally dominant forms of individual self-understanding; thus acceleration represents not only a formal parameter of the cultural modernization process but also to a great extent determines its direction substantively or in the dimension of content (Sachdimension). Therefore, modernization can in fact be seamlessly reconstructed as a process of social acceleration (figure 12.1, cf. chapter 1.2.b, figure 1.1).

This reconceptualization of the modernization process seems to be fruitful for the formation of social-scientific theories for two reasons: first, it makes possible a new view of the paradoxes and ambivalences of modernity and, second, it allows a precise definition of both rupture and continuity at the threshold between modernity and late modernity. I begin with the first.

Contrary to the diagnosis of an accelerated structural transformation, one can observe a complementary process of structural rigidification in the course of modernity. It is noticeable primarily in the autonomization and immunization of the operational logic of social systems. In particular, the mutual escalation of growth and acceleration standing at the center of this investigation appears to be an unavoidable structural compulsion that mercilessly propels the development of society and turns the “zero-growth option” into an unreachable utopia. “A seemingly paradoxical status quo bias and immobility of society as a whole appears to be to the flipside of the modernization process. There is nothing in common between this and the basic motif of modernity, the heightening of the capacity to dispose over and select among options,” finds Claus Offe, and indicates that the multiplication of options only occurs within the bounds set by the selection filters that govern systemic operations and grow increasingly narrow precisely as a result of the heightening of complexity that systems are compelled to achieve: “Regardless of how self-evident and commonplace they may sound, all these claims about growing choices over social contexts give not just a crude but a downright misleading and one-sided picture of the realities of a modern social structure. They serve me here merely as a foil against the backdrop of which I would like to consider the exactly opposite claim: namely, that it is precisely modern societies which are characterized by a high degree of rigidity and inflexibility.”9

12.1. The Modernization Process IIa

He comes to the conclusion that this structural rigidity is the result of the specific mode in which contingency is processed in modernity. Through specialization and functional differentiation, this mode simultaneously brings about 1. a tremendous heightening of complexity and thus contingency and, as a result, 2. a sharpening of the systemic processing filters with which political, economic, scientific, and legal problems are identified and “solved.” The more options multiply and change, the more “the institutional and structural premises according to which contingency operates . . . transcend being at our political, or even intellectual, disposition.”

Offe then tentatively derives from these considerations a principle of constant sums: “the more options that we make available to ourselves, the less optional is the institutional framework with whose help we make them available.”10 Transferred to the dialectic of movement and inertia, this constancy principle can illuminate social acceleration in a very instructive way with the help of the “motors” represented above in figure 7.1: the greater the dynamization of the three spheres of acceleration (techniques/technology, social change, the pace of life), the more fixed and unshakable the three external principles linking growth and acceleration and the (internal) circle of acceleration appear. Put otherwise, to the extent that the material structures of the lifeworld, the networks of relationships and associational structures, and the concrete value orientations, practices, and action orientations change, the abstract structural logics that drive substantial societal transformations harden into the “iron cage” bemoaned by Max Weber. Frenetic standstill therefore means that nothing remains the way it is while at the same time nothing essential changes. Furthermore, this paradoxical dualism of late modernity may help explain a peculiar phenomenon in the debate about globalization. The defenders of the cultural homogenization or convergence diagnosis seem to have arguments that are just as plausible as those of the partisans of the pluralization thesis: whether globalized societies are experienced as converging or diverging depends on whether one adopts a structure- or a content-oriented perspective.

“Structural crystallization” also obviously has massive consequences for the cultural development and self-perception of society. Thus it is tightly connected to the phenomenon of cultural rigidity in modernity. The counter-diagnosis here is that the rapid cultural change actually hides a lack of development. For reasons specifically arising from acceleration that I have worked out in previous chapters, the perception of an “end of history” and a “return of the ever same” even comes to overshadow the perception of profound transformation.11 Society thereby loses its character as a project, as something to be shaped through political action; it has exhausted, so it seems, its utopian energies and resources of meaning. Correspondingly, one can observe an astonishing stability and solidification on the cultural side of the modernization process, a fact that is quite susceptible to interpretation as ongoing “pattern maintenance,” to use Talcott Parsons’s term. From a cultural perspective, the value orientations of activism, universalism, rationalism, and individualism prove to be the necessary complementary principles of the mutually escalating interconnection of growth and acceleration.12

Therefore, from both cultural and structural points of view, the history of acceleration and modernity can also be told without contradiction as the story of a progressive rigidification whose traces are also visible from a psychological perspective, i.e., in relation to the development of personality and individual relations to self. As I have shown, the acceleration or compression of episodes of action and experience constantly threatens to flip over from a stimulating “heightening of sensory life” (Steigerung des Nervenlebens, Simmel) into its opposite, namely, the experience of an eventless, existential tedium (l’ennui) and, in extreme cases, even the pathological experience of the “frozen” time of depression. Our finding, then, is that in both the individual and the collective case the impression of a standstill (in spite of or precisely because of a very dynamic field of events) is created by the transition from a form of movement that is experienced as directed to a directionless dynamization.

Interestingly, Paul Virilio, who holds that the modern history of acceleration ceaselessy strives toward the frenetic standstill of a “polar inertia,”13 essentially bases his claim on technical acceleration and thus, in the end, on a perspective centered on society’s relation to nature. According to him, the progressive speed revolutions of transportation, transmission, and finally transplantation lead paradoxically to a growing physical immobility of, in the first place, the human body, but potentially of the whole material universe. The switch from forward motion with the help of one’s own bodily power to motion using the metabolic speed of external entities (e.g., riding horses or carriages) already slowed down the speed and movement of one’s own body. However, it was only in the wake of the “dromocratic revolution,” in which the discovery of technical speed replaced the metabolic, body-bound production of tempos, that human beings became a passively borne, more or less tied up, “parcel”: for instance, in automobiles, planes, and, above all, in rockets. In other words, they became by and large unmoving moved objects that sit tight in a “projectile” and are thereby also increasingly sealed off from the sensory experience of movement.14

Self-driven human and animal movement thus noticeably loses its social function.15 It is relegated to sport arenas and in this way, so to speak, turned into a “museum piece.” The fact that we have to move our bodies from time to time while we are, as it were, “idling,” i.e., not really going anywhere at all (for instance, running on treadmills), simply in order to keep them functional, just confirms their acceleration-historical obsolescence from this point of view. As I have argued in chapter 3, with the transition from transportation to transmission as the leading medium of acceleration, the movement of one’s own body across the surface of the earth is increasingly replaced by the “channeling and downloading” of the world through the TV and the computer: to the extent that physical mobility is replaced by much faster digital and virtual transmission, Virilio’s apocalyptic vision of polar inertia gains in plausibility.

Beyond this, the technologically accelerated mastery and processing of nature is accompanied by a growing risk of systematically incalculable breakdowns and accidents, as Charles Perrow showed in a much discussed study.16 These suddenly and unexpectedly bring the rapid processing of nature enabled by modern industrial technology to a standstill. So here again accelerated movement flips over into paralyzed inertia: a server crash in a computer network can illustrate this just as well as a necessary shutdown of a nuclear reactor. Thus rigidification (Erstarrung) indeed proves to be an inherently complementary principle of social acceleration in all four aspects of societal development (figure 12.2).

This also makes clear both how much the four paradoxical complementary principles of differentiation, rationalization, domestication, and individualization, which were introduced in chapter 1.2.b as descriptions of the modernization process, can be understood as consequences of social acceleration and how they are linked with the designated tendencies of rigidification (cf. figure 1.1). As I have shown, the processes of losing control (Steuerung) and disintegration that accompany the functional differentiation of society can be interpreted as an effect of desynchronization under conditions of acceleration. Moreover, the erosion of resources of meaning, as the “flip side” of rationalization that seemingly culminates in the extinguishing of meaning once and for all in posthistoire, is caused not least by the accelerated devaluation or invalidation of traditions, bodies of knowledge, and action routines as well as the continual alteration of associational structures. Further, the inversion of the mastery of nature into the destruction of nature (and the potential destruction of ourselves by nature) seems to be primarily a result of a lack of respect for the “intrinsic temporalities” of nature. Last, the widespread alarm in cultural criticism concerning a loss of autonomy (in “mass culture”) that paradoxically accompanies and complements the process of individualization is grounded in the acceleration-induced experience of “uprootedness” and/or “alienation.” Such an experience is expressed, for instance, in the growing feeling of not having any time (for that which is “genuinely” important) even though more and more time resources are being saved by means of technological acceleration.17

Thus the thesis that the basic processes of modernization identified in classical sociology can be interpreted from a specifically temporal perspective as mechanisms and manifestations of social acceleration has been confirmed. Individualization is a cause as well as an effect of social acceleration insofar as individuals are more mobile and flexible in adapting to social change and faster in making decisions than collectivities. Functional differentiation causes acceleration and at the same time represents a promising strategy in the face of the pressure to accelerate because it makes possible the externalization of costs and the acceleration of systemic processing, hence also the (mutually reinforcing) escalation and temporalization of complexity. The same holds true for processes of rationalization in the sense of efficiency increases in means-ends relationships and for processes of domestication in the sense of an escalation of exchange processes with nature. However, this still does not answer the question whether social acceleration constitutes an independent basic principle of modernization or rather merely opens up an illuminating perspective on modernity as defined by the other four processes and so, as it were, simply describes the temporal dimension of modernization.

I do indeed defend the thesis that social acceleration should be understood as an irreducible and tendentially dominant basic principle of both modernity and modernization for three interconnected reasons. In the first place, social acceleration and its underlying logic of escalation have proved in the course of the present work to be the unified principle that links together not only the four dimensions of modernization but also the various phases of the modernization process. We will come back to this point shortly. In the second place, however, the principle of acceleration has even turned out to be primary with regard to the other tendencies of modernization insofar as it can provide the key to explaining the historical changes in their manifestations. So, for instance, it was shown in chapter 7.1 that the various phases and manifestations of capitalism can be conceived as expressions of a unified logic of acceleration. Connected to this is the partial retraction or modification of “classical modern” forms of differentiation: as I have made clear, in late modernity many of the temporally and spatially differentiated social processes or spheres (e.g., the separation of realms of work and leisure, of commercial, cultural, and athletic institutions, etc.) are once again dedifferentiated. In the domain of social institutions a similar hybridization of economic, civil society, and state elements can be observed.18 Thus the developmental transition to postmodernity is frequently described in social diagnoses as a process of dedifferentiation and hybridization, one that even makes the boundaries between science and religion, culture and commerce, art and technology, economics and politics, etc., porous once again.19 I have interpreted this development by postulating that after the acceleration of the respective system processes, rigid system boundaries function as brakes on intersystemic exchange processes. From this point of view, the principle of differentiation itself could even prove to be a further element of the dialectic of acceleration and deceleration summarized in figure 8.1: it accelerated social processes in classical modernity, but increasingly becomes an impediment to acceleration in late modernity. Yet even if one can interpret the observable changes more as modifications of differentiation than as actual dedifferentiation (the other possibility of hybridizations on the level of the system codes is almost entirely ruled out from the start on conceptual grounds),20 it still appears to be the case that the process of differentiation formally follows the logic of acceleration.

This is even truer of the process of individualization. If one conceives of the unfolding of a self-determined, stable identity and the autonomous pursuit of a “life plan” in accordance with freely chosen but relatively time-resistant principles as the correlate or core of modern individualization,21 then the tendential development of late modern situational forms of identity can actually be understood as an acceleration-induced decline of individualization; in any case, however, it represents a serious change in the manifestations of this process.

Finally, indications of a modification or tendential retrogression of rationalization may be found wherever the substantial rationality of decisions or determinations sinks in favor of shorter processing and execution times, for example, in the legislature, the stock market, or in certain production decisions, or where the “situational” exploitation of contingent opportunity structures replaces the principles of a systematic conduct of life or even in phenomena such as the abandonment of the theoretical and deductive derivation and calculation of new combinations of active ingredients in chemistry in favor of the accidentally innovative products of excessive amounts of practical experimentation. From a perspective that is indifferent to the demands of time rationality, such phenomena can indeed be interpreted as forms of derationalization; but from a time-sensitive angle, in contrast, they seem to be rather modifications of the rationalization process under conditions of acceleration.22

In the third place, however, the weightiest and most consequential argument for the independence and potential dominance of social acceleration as a basic process of modernization lies in the fact that the results of my inquiry impressively confirm the assumption that the nature of individual and collective human existence has an essentially temporal and processual character, such that what an individual or society ultimately is is quite fundamentally determined by the time structures and time horizons of this existence. Transformations of the latter are therefore immediately transformations of the former and vice versa.23

Yet this holds true a fortiori for the analysis of modernity: when considered on its own, the structural and cultural nexus characterized by differentiation, rationalization, individualization, domestication and their paradoxical countertendencies seems to be an “ultrastable arrangement” and hence to guarantee the continuity of societal development as well as that of personal identity.24 Now with respect to this nexus, indeed, nothing has changed about the character of modernity. In my view, however, it is this constriction of perspective, this “forgetfulness of time,” that leads the critics of diagnoses of rupture to categorically reject any questioning of the continuity of modernity. Yet the fact that remains hidden from this involuntarily “static” view of modernity, and that first comes into view in a temporalized, acceleration-theoretical perspective, is that even though the basic framework of the principles of modernization (including the tendencies of growth and acceleration) persists unaltered and uncontested individuals and societies can be (and are) exposed to radical and fundamental transformation because of an alteration of their temporal structures. As I have argued here in part 4, it is an acceleration-induced transformation in the dimension of time that first allows the epochal breaks in the process of modernization to come to light and to be explained. It is what is responsible for the fact that individuals and societies from early modernity through “classical modernity” to late modernity were exposed to a wide-ranging, double transformation.

Table 12.1 summarizes this twofold transformation process and its characteristic dialectic of temporalization and detemporalization in an ideal-typically sharpened fashion. The guiding hypothesis here is that the dynamization of society and the acceleration of endogenous social change lead to a progressive alteration of the individual and collective experience of time and history. This also brings about a transformation of individual and collective sociopolitical self-relations as a consequence. I assume here that the effects of the modern process of dynamization do not operate in a linear way but rather reach critical points of inflection that are linked to the tempo of the succession of generations.25

If the tempo of social change that is systematically self-produced (and in this sense expected) becomes higher than the turnover rate of the three or at most four generations that coexist within a society at any given historical moment, then the space of experience and the horizon of expectation come apart: one expects something different from the future than one knows from the past. It seems that this threshold was crossed at the latest during the “epochal threshold” of the late eighteenth century in such an enduring way that the experience of history and the life perspectives of individuals have been correspondingly temporalized. History and life are temporalized, in the sense characteristic for “classical modernity,” insofar as they are projected into the future as malleable and susceptible to planning and thus bear the promise of individual and collective autonomy. Social acceleration thus sets history and identity in motion in a very specific way. The fundamental transformation of individual and political forms of selfhood that goes along with this is, from a historical point of view, unquestionable. Therefore, it cannot be weakened by a doubtlessly justified reference to the fact that premodern societies were not nearly so stable and static as the schema presented here suggests at first glance. In order to prevent misunderstandings, let me just point out once again that the model of historical development proposed here is not at all forced to deny or ignore any of the sometimes dramatic historical upheavals and phases of accelerated societal transformation in premodernity, for instance, subsequent to the Crusades or during the urban development that began in the high Middle Ages. The claim defended here is rather that unexpected or exogenous upheavals, however fast and violent they may be, do not lead by themselves to a temporalization of the horizon of expectation: they appear as more or less surprising “histories” within a per se static historical space, where they can possibly be repeated.26 Innovations that are, so to speak, erratic cannot be systematically located within a stable horizon of expectation. Thus even after a phase of upheavals sociocultural realignment occurs within the horizon of a situational, static experience of time and an orientation toward inherently enduring structures. Under such conditions, historical shocks do not bring about temporalization. Rather they cause a one-time transformation of the space of experience and the horizon of expectation, which quickly adjust and become restabilized in a more or less static form, though they naturally do have to systematically take into account the unpredictable vicissitudes of ordinary life.

TABLE 12.1 From “Temporalized” History to “Frenetic Standstill”: The Acceleration-Induced Dialectic of Temporalization and Detemporalization in Modernity

In contrast to this, “classical modern” society presents itself as a social order that, after its consolidation, changes continually, controllably, and above all in a directed and thus politically malleable process within a growing framework of institutional safeguards against those vicissitudes and hence precisely without dramatic structural upheavals.27

The temporalization of individual life in “classical modernity” first takes root on a broad scale sometime after the temporalization of history does, lagging behind the latter until around the end of the nineteenth century. Two factors may be responsible for this: on the one hand, the biographical and identity-constituting orientation toward a planned-out, temporally extended life course needed an institutional safeguard in the structures of the nascent welfare state, which was for its own part a product of the historical conceptualization of society as a project to be shaped politically. On the other hand, however, this time lag may reflect the fact that the temporalization of one’s own individual life seems to be more strongly bound to a genuinely generational rate of change, whereas the temporalization of the horizon of history could already set in as a consequence of the acceleration of the historical rate of change beyond the critical threshold of three (or four) coexisting generations. A possible reinforcement of this argument lies in the fact that at the second threshold, namely, that of an intragenerational rate of change and hence a late modern temporalization of time, no corresponding shift to a new phase can be observed.28

Interestingly, alongside the temporalization of (social) history observed by Koselleck there is also a temporalization of the perceptual patterns of the natural sciences. According to Wolf Lepenies, it is precisely during this period that the view of a categorial juxtaposition of natural things is increasingly replaced by the analysis of their succession in developmental histories.29

However, what is of decisive importance is that the temporalization of life and of history in the sense of their progressive motion along preestablished pathways was accompanied and supported by the formation of a stable institutional arrangement that was centered, on the one hand, around the national state institutions of law, democracy, and security apparatuses and, on the other hand, around those of the welfare state, marriage, and the classical modern labor regime that constituted the material foundation of the institutionalization of the “life course regime.”

But the dynamization of society and self-relations did not stop there. Toward the end of the twentieth century it reached the critical threshold of an intragenerational rate of change, which once again brought in train severe mutations in the individual and collective experience of time and hence also in the dominant forms of individual and sociopolitical identity. At the same time, it led to a steadily advancing erosion of the classical modern institutional arrangement, which likewise fell under pressure to become more dynamic (cf. figure 8.1).30 Now time itself is temporalized, that is, the various qualities that define temporality such as the point in time, the sequence, the duration, the rhythm, and the tempo of events and actions are no longer determined in accordance with a “metatemporal,” preinstitutionalized plan, but are rather decided within time itself. This has serious consequences in the form of a “detemporalization” of history and life, which thereby lose the character of directed, planned temporal processes. The ubiquitous simultaneity of late modernity that rests on this constellation is thus, strictly speaking, no longer a simultaneity of the nonsimultaneous, since that presupposes the idea of a temporalized, directed, and moving (though asynchronous) history. Instead, it is, as it were, a static, situational, “timeless,” and orderless simultaneity of historical fragments.31

As the replies of Barbara Adam and Carmen Leccardi to an earlier version of my temporalization thesis have made clear,32 the concepts I have chosen easily give rise to a confusion, the cause of which lies once again in the very inconsistent conceptual repertoire of the contemporary debate concerning the philosophy and sociology of time. Just as the phenomenon of the future becoming contingent or uncertain can be apprehended under the concept of the contraction of the present (Lübbe) as well as the “extension of the present” (Nowotny), so too the late modern development of a ubiquitous simultaneity that determines the temporal qualities of events and processes in daily life, life as a whole, and in historical time during the course of their performance gets described using the catchword of “timeless” time (Castells) as well as the concept of “temporalized” time (Luhman and Hörning, Ahrens, and Gerhard). In both the latter cases the same thing is meant: since nothing can be said beforehand about the sequences, speeds, rhythms, and durations of events, time appears to some as detemporalized (it lacks the corresponding basic qualities), but to others it seems only now to be truly temporalized (the specific form those qualities take is decided within time).

Consequently, I suggest that from a conceptual point of view this development can be most clearly described as a temporalization of time and a detemporalization of history, life, and also partly of everyday practice. What has been lost are the, so to speak, “metatemporal” plans of history, life, and daily activities that determined the temporal qualities of events and actions beforehand and made the time of everyday practice, of life, and of history susceptible to planning and allowed them to appear directed.

Thus, regardless of the terminological confusion, it seems to me that the arguments are in both cases unmistakable and clear. Nevertheless, one must keep in mind that I am using the concept of temporalized time in the social-phenomenological or systems-theoretical sense described earlier and not (as Adam erroneously assumes) in the philosophical meaning proposed, with varying accents, by Bergson, Mead, and particularly Heidegger, one that was above all directed against the notion of clock time. So “temporalization of time” does not mean anything like the return to the “originary temporality of Dasein” that constitutes itself out of the certainty of death and hence out of an authentic future that first brings forth and connects the present and the past.33 From a Heideggerean perspective, the late modern form I have in mind would appear to be rather a radicalized “flight in the face of what passes” (Flucht vor dem Vorbei)34 and hence from the authentic core of the temporality of Dasein in the “anyone’s time” (Man-Zeit) that is caught up in the present, or in other words, as a radicalized detemporalization.35

In any case, as a diagnosis of the times the core thesis of part 4 runs as follows. It is above all the transformation of the socially dominant experience of time, grounded in the acceleration-induced dialectic of temporalization and detemporalization, that has led to two key conditions: the rigidifying side of the relationship of complementarity between movement and inertia has gained the upper hand in the cultural self-perception of late modernity and the related autonomization of systemic processes appears to be irreversible. Thus the observations of an “end of history” diagnose nothing more than the end of the temporalized history of modernity, i.e., the end of an experience of time in which historical development and the unfolding of one’s life history appeared to be both directed and controllable, hence in which changes bore, as it were, visible indexes of movement. In late modernity this is replaced by the experience of unforeseeable and undirected, and hence, as it were, unmoving, un-(trans-situationally) controllable, and continuous change. The “law of acceleration” postulated by Henry Adams can no longer be understood as a “law of progress.” Insofar as the modern promise of progress was the promise of individual and political autonomy, the transition to this experience of time is diametrically opposed to the idea of progress. For I follow Jürgen Habermas in holding that the project of modernity is centered on the idea that persons can and should themselves take responsibility for the progressive shaping of their own individual lives (ethical autonomy) and their collective form of life (political autonomy).36 Yet the new experience of time is constitutively related to the feeling of a loss of autonomy that is manifested in the disappearance of any possibility of control and the erosion of opportunities to shape one’s own affairs. It leads individually to the experience of drift, or, put positively, of situationally open play, and politically to the fatalism of a rhetoric of objective forces and inevitable structural adjustment.

Thus Claus Offe comes to the conclusion that “precisely as a result of rapid modernization and rationalization processes, societies can regress into a condition of mute condemnation to fate and inflexibility, the overcoming of which was the original motive of processes of modernization,” and Peter Sloterdijk complains that “modernity left all to itself” evidently no longer has any strength “to fend off its fatal drift; before our very eyes enlightened secularism, with its double commitment to self-determination and large-scale technology, seems to be saying goodbye in the midst of a global state of neglect—things now run as they please, human intentions are no longer necessary.”37 Sloterdijk also diagnoses the emergence of a “second fatalism.”

In this way the core of modernization, the acceleration process, has turned against the very project of modernity that originally motivated, grounded, and helped set it in motion. Indeed, the acceleration process appeared to be what was promising in the possibility of modernity: growth and acceleration served as the societal precondition on which the promise of autonomy, in the sense of a liberation from material and social compulsions of all forms, was based. As I have shown, it was not least visions of progress and utopian energies that drove social acceleration in early and classical modernity before it became so independently entrenched (verselbtständigte) in the structures of modernity that it no longer needed a pronounced orientation toward the future to maintain itself. However, it is now precisely the relationship of mutual escalation between growth and acceleration and its impact on temporal structures that is beginning to undermine the promise of autonomy in an ever sharper fashion. It has become an inescapable compulsion. The conclusion my arguments yield is thus that the project of modernity itself can be placed among the classical modern accelerators that now fall under a growing pressure of erosion as late modern “brakes.” What was once an alluring possibility now appears to be a threat. The original promise of happiness presented by growth and acceleration is noticeably waning and being transformed into the curse of an ever increasing endangerment of individual and collective autonomy.

The compulsion to accelerate that is rooted in the social structure of “slipping slopes” forces people, organizations, and governments into a reactive situational attitude instead of a self-determining conduct of individual and collective life. According to Virilio, they thus begin to look like a racing car driver who, in the face of the highly automated processes he is trying to control, “is no more than a worried lookout for the catastrophic possibilities of his own movement.”38 However, taken by itself, this image is misleading because it suggests a direct reduction of options. Social acceleration does not simply erode potentials for autonomy in a unilinear way. Instead it makes their use problematic precisely by multiplying them. Despite all the uncertainties and dangers, for individuals the temporalization of time in everyday practice and the life course always means in the first place an immense growth in the number of possible decisions and the temporal horizons of availability, precisely because actions and events become more freely sequenceable, combinable, and revisable. Further, in politics the setting aflow of the solidified institutional arrangements of “classical modernity” opens up maneuvering room and new organizational possibilities. Nevertheless, these developments become autonomy-endangering precisely through the transformation of the late modern time structures with which they are linked. The self-determined organization of individual and/or collective life presupposes 1. that the space of options remains stable for a certain period of time (since well-grounded decisions become impossible when their utility, opportunity costs, and consequences cannot be foreseen with a certain minimal temporal stability), 2. that conditions of action are enduring enough for processes of change to be comprehensible and at least partly controllable, and finally 3. that there is sufficient time available to actually shape the spaces of action that constitute life and society through planned intervention.

Therefore, the possibility of genuine ethical and political self-determination also depends on the formation of time-resistant or trans-situational preferences and goals according to which organization, progress, and movement can be defined and measured. Autonomy in this sense is equivalent to the temporally stable pursuit of self-determined plans even against the resistance of changing situational conditions. Naturally this does not exclude the revision of these plans within time itself, but these changes should not exclusively be induced by external forces or be entirely situation dependent, that is, the urgency of the fixed term and the pragmatic necessity of holding options open must not hinder the formation and pursuit of a self-determined preference ordering.

Thus, to the extent that the institutions safeguarding this stability dissolve under the pressure to dynamize and identities and political programs do indeed become situational, the horizons of choice become politically and ethically unfruitful. This is due not least to the fact that the holding open of options and opportunities becomes a categorical imperative in view of uncertainty regarding the future conditions of action and decision. But this imperative cuts ever more strongly against substantial bonds, and this in turn produces a state in which experiences have little power to bind expectations and hence in which the connection between past, present, and future, both individually and politically, is sundered in such a way that the supposedly autonomous spaces for organization turn into a static space of fatalistic standstill. Here the return of the ever same, the “timeless time” of what is at once eternal and ephemeral, of what is, in the words of the schoolgirl cited at the beginning of the chapter, simultaneously hectic and rigid, is hidden behind the rapid turnover of episodes. In such a context the very idea of organizing or shaping (Gestaltung) becomes literally meaningless.39 The full significance of this dilemma is first revealed in a truly paradoxical historical situation in which the technical and social presuppositions for a political shaping of society (particularly in light of burgeoning genetic technology and the extinguishing of the binding force of tradition) are more favorable than ever, while the actual organizational possibilities (Gestaltungsmöglichkeiten) seem to be even scarcer than in premodernity for temporal-structural reasons.

The break between classical and late modernity can therefore be quite exactly determined as the moment in the “history of acceleration” at which the forces of acceleration so greatly surpass the organizational and integrative capacity of individuals and societies that the temporalization of life and of history is supplanted by the temporalization of time itself and thus replaced by the latter as the dominant experience of time. It is also, therefore, the moment at which the cultural project and the structural process of modernization come into insurmountable contradiction.40 Furthermore, this moment is closely tied to the fact that the speed of social change crosses the generational threshold and heads toward an intra generational pace that erodes the conditions of continuity and coherence for stable personal identities, thus creating massive difficulties for the formation of time-resistant preferences.

The resulting state of affairs only appears problematic or even worthy of lament as long as one believes that the normative project of modernity must be sustained. An abandonment of the ideal of autonomy and the connected claim to shape and control circumstances thus opens up the possibility of a positive relationship to the autonomization of the modernization process and the new modes of time experience, something that is expressed in the affirmative stance toward acceleration in philosophies of postmodernity. From their perspective, the claim to be able to theoretically understand and adequately describe societal development,41 and to shape it practically through political action, is delusory and always already latently totalitarian. This claim, which is now untenable for temporal-structural reasons, must be given up. The resulting loss of control is celebrated as a liberation from a compulsion to control that, even in classical modernity, could only be maintained by formidable social demands of continuity, integration, and coherence (the “terrorism of identity”). Therefore, so the argument goes, social acceleration does not simply undermine the possibility of subjectivity per se; it also liberates it from restrictive demands of stability.42 Social fragmentation and desynchronization and the absence of an integration of experiences into an identity-constituting whole can be affirmed as pleasurable and satisfying just insofar as it is possible to develop an ironic, playful relation to the uncontrollable vicissitudes of life and to do without a representation of the world as a meaningful whole and enduring bonds to places, people, practices and values.43

Our confrontation in this work with the self-autonomizing acceleration dynamic of modernity has at several places brought to light arguments against such an uncritical affirmation of hyperacceleration. They relate, for instance, to the fundamental conditions of cultural reproduction, the presuppositions of a minimally sufficient amount of social synchronization, or the quasi-anthropological givens of time experience. I will not repeat any of the details of these arguments here. Beyond the ethical and political critique from within the horizon of classical modernity, the doubts are, above all, addressed to the question of the consequences that unchecked further dynamization would have for the earth’s ecosystem, for the various modes of the (temporal) “structural coupling” of desynchronized social subsystems, for the maintenance of the sociomoral conditions of the existence of society and intergenerational cultural transfer, and finally, for the possibility of experiencing the world as meaningful. They make clear that the determination of the temporal-structural or speed limits of subjectivity and sociality require, so to speak, a critical theory of acceleration that is capable of identifying acceleration-induced social pathologies without relying on the normative criteria of a now questionable philosophical anthropology or philosophy of history.44 Peter Sloterdijk suggested this path more than a decade ago in his attempt to develop a “critique of political kinetics” and of “mobilization” that he wanted to understand as a third version of critical theory. Marx and the Frankfurt School had supposedly failed by misunderstanding or even uncritically supporting the immense kinetic forces of modernity.45 However, Sloterdijk’s own conception remains highly speculative, rather unsystematic, and lacking an empirical grounding. Therefore, in the conclusion I would like to sketch out, drawing on a summary of the argument of the book, an outline of a critical theory of acceleration. At the same time, I will sound out the various scenarios that remain open with regard to the continuation of the modern history of acceleration.