CHAPTER THREE

Let Sunday’s Degradation Rituals Begin

AS EACH OF the blindfolded prisoners is escorted down the flight of steps in front of Jordan Hall into our little jail, our guards order them to strip and remain standing naked with their arms outstretched against the wall and legs spread apart. They hold that uncomfortable position for a long time as the guards ignore them because they are busy with last-minute chores, like packing away the prisoners’ belongings for safekeeping, fixing up their guards quarters, and arranging beds in the three cells. Before being given his uniform, each prisoner is sprayed with powder, alleged to be a delouser, to rid him of lice that might be brought in to contaminate our jail. Without any staff encouragement, some guards begin to make fun of the prisoners’ genitals, remarking on their small penis size or laughing at their unevenly hanging testicles. Such a guy thing!

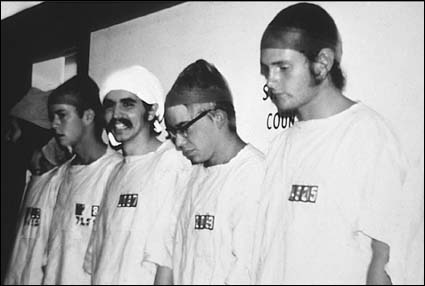

Still blindfolded, each prisoner is then given his uniform, nothing fancy, just a smock, like a tan muslin dress, with numbers on front and back for identification. The numbers have been sewn on from sets we bought from a Boy Scout supply store. A woman’s nylon stocking serves as a cap covering the long hair of many of these prisoners. It is a substitute for the head shaving that is part of the newcomer ritual in the military and some prisons. Covering the head is also a method of erasing one of the markers of individuality and promoting greater anonymity among the prisoner caste. Next, each prisoner dons a pair of rubber clogs, and a locked chain is attached to one ankle—a constant reminder of imprisonment. Even when he is asleep, the prisoner will be reminded of his status when the chain hits his foot as he turns in his sleep. The prisoners are allowed no underwear, so when they bend over their behinds show.

When the prisoners have been fully outfitted, the guards remove the blindfolds so that the prisoners can reflect on their new look in the full-length mirror propped against the wall. A Polaroid photo documents each prisoner’s identity on an official booking form, where an ID number replaces “Name” on the form. The humiliation of being a prisoner has begun, much as it does in many institutions from military boot camps to prisons, hospitals, and low-level jobs.

“Don’t move your head; don’t move your mouth; don’t move your hands; don’t move your feet; and don’t move anything. Now shut up, and stay where you are,” barks Guard Arnett in his first show of authority.

1 He and the other day shift guards, J. Landry and Markus, are already starting to wield their police billy clubs in menacing positions as they undress and outfit the prisoners. The first four prisoners are lined up and told some of the basic rules, which the guards and the warden had formulated during the guard orientation on the previous day. “I don’t like the warden to correct my work,” says Arnett, “so I will make it desirable for you

not to have to correct me. Listen carefully to these rules. You must address prisoners by number and by number only. Address guards as ‘Mr. Correctional Officer.’”

As more prisoners are brought into the Yard, they are similarly deloused, outfitted, and made to join their fellows standing against the wall for indoctrination. The guards are trying to be very serious. “Some of you prisoners already know the rules, but others of you have shown you don’t know how to act, so you need to learn them.” Each rule is read slowly, seriously, and authoritatively. The prisoners are slouching, shuffling, gazing around this strange new world. “Stand up straight, number 7258. Hands at your sides, prisoners.”

Arnett begins to quiz the prisoners on the rules. He is demanding and critical, working hard to set a serious tone in official military manner. His style seems to say that he is just doing his job, nothing personal intended. But the prisoners are having none of that; they are giggling, laughing, not taking him seriously. They are hardly into playing their role as prisoners—yet.

“No laughing!” orders Guard J. Landry. Stocky, with long, shaggy blond hair, Landry is about six inches shorter than Arnett, who is a tall, slim fellow with aquiline features, dark brown curly hair, and tightly pursed lips.

Suddenly, Warden David Jaffe enters the jail. “Stand at attention against this wall for the full rule reading,” says Arnett. Jaffe, who is actually one of my undergraduate Stanford students, is a little guy, maybe five feet five, but he seems to be taller than usual, standing very erect, shoulders back, head held high. He is already into his role as the warden.

I am watching the proceedings from a small scrim-covered window behind a partition that conceals our videocamera, Ampex taping system, and a tiny viewing space at the south end of the Yard. Behind the scrim, Curt Banks and others on our research team will record a series of special events throughout the next two weeks, such as meals, prisoner count-offs, visits by parents, friends, and a prison chaplain, and any disturbances. We don’t have sufficient funds to record continuously, so we do so judiciously. This is also the site where we experimenters and other observers can look in on the action without disturbing it and without anyone being aware of when we are taping or watching. We can observe and tape-record only that action taking place directly in front of us in the Yard.

Although we cannot see into the cells, we can listen. The cells are bugged with audio devices that enable us to eavesdrop on some of the prisoners’ talk. The prisoners are not aware of the hidden microphones concealed behind the indirect lighting panels. This information will be used to let us know what they are thinking and feeling when in private, and what kinds of things they share with one another. It may also be useful in identifying prisoners who need special attention because they are becoming overly stressed.

I am amazed at Warden Jaffe’s pontificating and surprised at seeing him all dressed up for the first time in a sports jacket and tie. His clothing is rare for students in these hippie days. Nervously, he twirls his big Sonny Bono mustache, as he gets into his new role. I have told Jaffe that this is the time for him to introduce himself to this new group of prisoners as their warden. He is a bit reluctant because he is not a demonstrative kind of guy; he is lower-key, quietly intense. Because he was out of town, he did not take part in our extensive setup plans but arrived just yesterday, in time for the guard orientation. Jaffe felt a little out of the loop, especially since Craig and Curt were graduate students, while he was only an undergraduate. Perhaps he also felt uneasy because he was the littlest one among our otherwise all six-foot-plus-tall staff. But he stiffens his spine and comes on as strong and serious.

“As you probably already know, I am your warden. All of you have shown that you are unable to function outside in the real world for one reason or another. Somehow, you lack the sense of responsibility of good citizens of this great country. We in this prison, your correctional staff, are going to help you to learn what your responsibility as citizens of this country is. You heard the rules. Sometime in the very near future there will be a copy of the rules posted in each cell. We expect you to know them and be able to recite them by number. If you follow all of these rules, keep your hands clean, repent for your misdeeds, and show a proper attitude of penitence, then you and I will get along just fine. Hopefully I won’t have to be seeing you too often.”

It was an amazing improvisation, followed by an order from Guard Markus, talking up for the first time: “Now you thank the warden for his fine speech to you.” In unison, the nine prisoners shout their thanks to the warden but without much sincerity.

THESE ARE THE RULES YOU WILL LIVE BY

The time has come to impose some formality on the situation by exposing to the new prisoners the set of rules that will govern their behavior for the next few weeks. With all the guards giving some input, Jaffe worked out these rules in an intense session yesterday at the end of the guard orientation.

2

Guard Arnett talks it over with Warden Jaffe, and they decide that Arnett will read the full set of the rules aloud—his first step in dominating the day shift. He begins slowly and with precise articulation. The seventeen rules are:

- Prisoners must remain silent during rest periods, after lights out, during meals, and whenever they are outside the prison yard.

- Prisoners must eat at mealtimes and only at mealtimes.

- Prisoners must participate in all prison activities.

- Prisoners must keep their cell clean at all times. Beds must be made and personal effects must be neat and orderly. Floors must be spotless.

- Prisoners must not move, tamper with, deface, or damage walls, ceilings, windows, doors, or any prison property.

- Prisoners must never operate cell lighting.

- Prisoners must address each other by number only.

- Prisoners must always address the guards as “Mr. Correctional Officer” and the Warden as “Mr. Chief Correctional Officer.”

- Prisoners must never refer to their condition as an “experiment” or “simulation.” They are imprisoned until paroled.

“We are halfway there. I hope you are paying close attention, because you will commit each and every one of these rules to memory, and we will test at random intervals,” the guard forewarns his new charges.

| 10. |

Prisoners will be allowed 5 minutes in the lavatory. No prisoner will be allowed to return to the lavatory within 1 hour after a scheduled lavatory period. Lavatory visitations are controlled by the guards. |

| 11. |

Smoking is a privilege. Smoking will be allowed after meals or at the discretion of the guard. Prisoners must never smoke in the cells. Abuse of the smoking privilege will result in permanent revocation of the smoking privilege. |

| 12. |

Mail is a privilege. All mail flowing in and out of the prison will be inspected and censored. |

| 13. |

Visitors are a privilege. Prisoners who are allowed a visitor must meet him or her at the door to the yard. The visit will be supervised by a guard, and the guard may terminate the visit at his discretion. |

| 14. |

All prisoners in each cell will stand whenever the warden, the prison superintendent, or any other visitors arrive on the premises. Prisoners will wait on orders to be seated or to resume activities. |

| 15. |

Prisoners must obey all orders issued by guards at all times. A guard’s order supersedes any written order. A warden’s order supersedes both the guard’s orders and the written rules. Orders of the superintendent of the prison are supreme. |

| 16. |

Prisoners must report all rule violations to the guards. |

“Last, but the most important, rule for you to remember at all times is number seventeen,” adds Guard Arnett in an ominous warning:

| 17. |

Failure to obey any of the above rules may result in punishment. |

Later on in the shift, Guard J. Landry decides that he wants some of the action and rereads the rules, adding his personal embellishment: “Prisoners are a part of a correctional community. In order to keep the community running smoothly, you prisoners must obey the following rules.”

Jaffe nods in agreement; he already likes to think of this as a prison community, in which reasonable people giving and following rules can live harmoniously.

The First Count in This Strange Place

According to the plan developed by the guards at their orientation meeting the day before, Guard J. Landry continues the process of establishing the guards’ authority by giving instructions for the count. “Okay, to familiarize yourselves with your numbers, we are going to have you count them off from left to right, and fast.” The prisoners shout out their numbers, which are arbitrary four- or three-digit numbers on the front of their smocks. “That was pretty good, but I’d like to see them at attention.” The prisoners reluctantly stand erect at attention. “You were too slow in standing tall. Give me ten push-ups.” (Push-ups soon become a staple in the guards’ control and punishment tactics.) “Was that a smile?” Jaffe asks. “I can see that smile from down here. This is not funny, this is serious business that you have gotten yourselves into.” Jaffe soon leaves the Yard to come around back to confer with us on how he did in his opening scene. Almost in unison, Craig, Curt, and I give him a pat on the ego: “Right on, Dave, way to go!”

Initially the purpose of counts, as in all prisons, is an administrative necessity to ensure that all prisoners are present and accounted for, that none has escaped or is still in his cell sick or needing attention. In this case, the secondary purpose of the counts is for prisoners to familiarize themselves with their new numbered identity. We want them to begin thinking of themselves, and the others, as prisoners with numbers, not people with names. What is fascinating is how the nature of the counts is transformed over time from routine memorizing and reciting of IDs to an open forum for guards to display their total authority over the prisoners. As both groups of student research participants, who are initially interchangeable, get into their roles, the counts provide public demonstration of the transformation of characters into guards and prisoners.

The prisoners are finally sent into their cells to memorize the rules and get acquainted with their new cellmates. The cells, designed to emphasize the ambient anonymity of prison living conditions, are actually reconstructed small offices, ten by twelve feet in size. For the office furniture we substituted three cots, pushed together side by side. The cells are totally barren of any other furniture, except for Cell 3, which has a sink and faucet, which we have turned off but which the guards can turn back on at will to reward designated good prisoners put into that special cell. The office doors were replaced with specially made black doors fitted with a row of iron bars down a central window, with each of the three cell numbers prominently displayed on the door.

The cells run the length of the wall down the right side of the Yard, as it appears from our vantage point behind the one-way observation screen. The Yard is a long, narrow corridor, nine feet wide and thirty-eight feet long. There are no windows, simply indirect neon lighting. The only entrance and exit is at the far north end of the corridor, opposite our observation wall. Because there is only a single exit, we have several fire extinguishers handy in case of a fire, by order of the Stanford University Human Subjects Research Committee, which reviewed and approved our research. (However, fire extinguishers can also become weapons.)

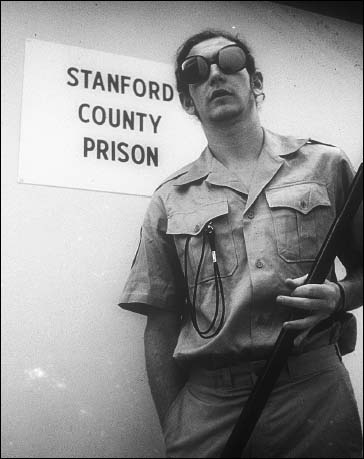

Yesterday, the guards posted signs on the walls of the Yard, designating this “The Stanford County Jail.” Another sign forbade smoking without permission, and a third indicated, ominously, the location of solitary confinement, “the Hole.” Solitary consisted of a small closet in the wall opposite the cells. It had been used for storage, and its file boxes took up all but about a square yard of open space. That is where unruly prisoners would spend time as punishment for various offenses. In this small space, prisoners would stand, squat, or sit on the floor in total darkness for the length of time ordered by a guard. They would be able to hear the goings-on outside on the Yard and hear all too well anyone banging on the doors of the Hole.

The prisoners are sent to their arbitrarily assigned cells: Cell 1 is for 3401, 5704, and 7258; Cell 2 is for 819, 1037, and 8612; while Cell 3 houses 2093, 4325, and 5486. In one sense, this is like a prisoner-of-war situation wherein a number of the enemy are captured and imprisoned as a unit, rather than like a civilian prison, where there is a preexistent prisoner community into which each new inmate is socialized and into which prisoners are always entering and being paroled out of.

All in all, our prison was a much more humane facility than most POW camps—and certainly more commodious, clean, and orderly than the hard site at Abu Ghraib Prison (which, by the way, Saddam Hussein made notorious for torture and murder long before American soldiers did more recently). Yet, despite its relative “comfort,” this Stanford prison would become the scene of abuses that eerily foreshadowed the abuses of Abu Ghraib by Army Reserve Military Police years later.

Role Adjustments

It takes a while for the guards to get into their roles. From the Guard Shift Reports, made at the end of each of the three different shifts, we learn that Guard Vandy feels uneasy, not sure what it takes to be a good guard, wishes he had been given some training, but thinks it is a mistake to be too nice to the prisoners. Guard Geoff Landry, kid brother of J. Landry, reports feeling guilty during the humiliating degradation rituals in which the prisoners had to stand naked for a long time in uncomfortable positions. He is sorry that he did not try to stop some things of which he did not approve. Instead of raising an objection, he just left the Yard as often as possible rather than continue to experience these unpleasant interactions. Guard Arnett, a graduate student in sociology, who is a few years older than the others, doubts that the prisoner induction is having its desired effect. He thinks that the security on his shift is bad and the other guards are being too polite. Even after this first day’s brief encounters, Arnett is able to single out those prisoners who are troublemakers and those who are “acceptable.” He also points out something that we missed in our observations but Officer Joe had remarked about during the arrest of Tom Thompson—a concern about Prisoner 2093.

Arnett doesn’t like the fact that Tom-2093 is “too good” in his “rigid adherence to all orders and regulations.”

3 (Indeed, 2093 will later be disparagingly nicknamed “Sarge” by the other prisoners precisely because of his militaristic style of obediently following orders. He has brought some strong values into our situation that may come into conflict with those of the guards, something to notice as we go along. Recall that it was something also noticed about Tom by the arresting police officer.)

In contrast, Prisoner 819 considers the whole situation quite “amusing.”

4 He found the first counts rather enjoyable, “just a joke,” and he felt that some of the guards did as well. Prisoner 1037 had watched as all the others were processed in the same humiliating fashion as he was. However, he refused to take any of it seriously. He was more concerned with how hungry he had become, having eaten only a small breakfast and expecting to be fed lunch, which never came. He assumed that the failure to provide lunch was another arbitrary punishment inflicted by the guards, despite the fact that most prisoners had been well behaved. In truth, we had simply forgotten to pick up lunch because the arrests had taken so long and there was so much for us to deal with, which included a last-minute cancellation by one of the students assigned to the guard role. Fortunately, we got a replacement from the original pool of screened applicants for the night shift, Guard Burdan.

The Night Shift Takes Over

The night shift guards arrive before their starting time at 6 P.M. to don their new uniforms, try on the sleek silver reflecting sunglasses, and equip themselves with whistles, handcuffs, and billy clubs. They report to the Guards’ Office, located down a few steps from the entrance to the Yard, in a corridor that also houses the offices of the warden and the superintendent, each with his own sign printed on the door. There the day shift guards greet their new buddies, tell them that everything is under control and everything is in place, but add that some prisoners are not yet fully with the program. They deserve watching, and pressure should be applied to get them into line. “We’re gonna do that just fine, you’ll see a straight line when you come back tomorrow,” boasts one of the newcomer guards.

The first meal is finally served at seven o’clock. It’s a simple one, offered cafeteria style on a table set out in the Yard.

5 There is room for only six inmates at the table, so when they finish the remaining three come to eat what is left. Right off, Prisoner 8612 tries to talk the others into going on a sit-down strike to protest these “unacceptable” prison conditions, but they are all too hungry and tired to go along right now. 8612 is wise guy Doug Karlson, the anarchist who gave the arresting cops some lip.

Back in their cells, the prisoners are ordered to remain silent, but 819 and 8612 disobey, talk loudly and laugh, and get away with it—for now. Prisoner 5704, the tallest of the lot, has been silent until now, but his tobacco addiction has gotten to him, and he demands that his cigarettes be returned to him. He’s told that he has to earn the right to smoke by being a good prisoner. 5704 challenges this principle, saying it is breaking the rules, but to no avail. According to the rules of the experiment, any participant could leave at any time, but this seems to have been forgotten by the disgruntled prisoners. They could have used the threat to quit as a tactic to improve their conditions or reduce the mindless hassling they endured, but they did not as they slowly slipped more deeply into their roles.

Warden Jaffe’s final official task of this first day is to inform the prisoners about Visiting Nights, which are coming up soon. Any prisoners who have friends or relatives in the vicinity should write to them about coming to visit. He describes the letter-writing procedures and gives each one who asks for it a pen, Stanford County Jail stationery, and a stamped envelope. They are to complete their letters and return these materials by the end of the brief “writing period.” He makes it clear that the guards have discretion to decide whether anyone will not be allowed to write a letter, because he has failed to follow the rules, did not know his prisoner ID number, or for any other reason a guard may have. Once the letters are written and handed to the guards, the prisoners are ordered back out of their cells for the first count on the night shift. Of course, the staff reads each letter for security purposes, also making copies for our files before mailing them out. The lure of Visiting Night and the mail, then, become tools that the guards use instinctively and effectively to tighten their control on the prisoners.

The New Meaning of Counts

Officially, as far as I was concerned, the counts were supposed to serve two functions: to familiarize the prisoners with their ID numbers and to establish that all prisoners were accounted for at the start of each guard shift. In many prisons, the counts also serve as a means of disciplining the prisoners. Though the first count started out innocently enough, our nightly counts and their early-morning counterparts would eventually escalate into tormenting experiences.

“Okay, boys, now we are going to have a little count! Going to be a lot of fun,” Guard Hellmann tells them with a big grin. Guard Geoff Landry quickly adds, “The better you do it, the shorter it’ll be.” As the weary prisoners file out into the yard, they are silent and sullen, not looking at one another. It has already been a long day, and who knows what’s in store before they can finally get a good night’s sleep.

Geoff Landry takes command: “Turn around, hands against the wall. No talking! You want this to last all night? We’re going to do this until you get it right. Start by counting off in ones.” Hellmann adds his two cents: “I want you to do it fast, and I want you to do it loud.” The prisoners obey. “I didn’t hear it very well, we’ll have to do it again. Guys, that was awful slow, so once again.” “That’s right,” Landry chimes in, “we’ll have to do it again.” As soon as a few numbers are called out, Hellmann yells, “Stop! Is that loud? Maybe you didn’t hear me right, I said loud, and I said clear.” “Let’s see if they can count backwards. Now try it from the other end,” Landry says playfully. “Hey! I don’t want anybody laughing!” Hellmann says gruffly. “We’ll be here all night until we get it right.”

Some of the prisoners are becoming aware that a struggle for dominance is going on between these two guards, Hellmann and the younger Landry. Prisoner 819, who has not been taking any of this seriously, begins to laugh aloud as Landry and Hellmann one-up each other at the prisoners’ expense. “Hey, did I say that you could laugh, 819? Maybe you didn’t hear me right.” Hellmann is getting angry for the first time. He gets right up in the prisoner’s face, leans on him, and pushes him back with his billy club. Now Landry pushes his fellow guard aside and commands 819 to do twenty push-ups, which he does without comment.

Hellmann moves back to center stage: “This time, sing it.” As the prisoners start to count off again, he interrupts. “Didn’t I say that you had to sing? Maybe you gentlemen have those stocking caps too tight around your head and you can’t hear me too well.” He is becoming more creative in control techniques and dialogue. He turns on Prisoner 1037 for singing his number off key and demands twenty jumping jacks. After he finishes, Hellmann adds, “Would you do ten more for me? And don’t make that thing rattle so much this time.” Because there is no way to do jumping jacks without the ankle chain making noise, the commands are becoming arbitrary, but the guards are beginning to take pleasure in giving commands and forcing the prisoners to execute them.

Even though it is funny to have the prisoners singing numbers, the two guards alternate in saying “There’s nothing funny about it” and complaining “Oh, that’s terrible, really bad.” “Now once more,” Hellmann tells them. “I’d like you to sing, I want it to sound sweet.” Prisoner after prisoner is ordered to do more push-ups for being too slow or too sour.

When the replacement guard, Burdan, appears with the warden, the dynamic duo of Hellmann and Landry immediately switches to having the prisoners count off by their prison ID numbers and not just their lineup numbers from one to nine, as they had been doing, which of course, made no official sense. Now Hellmann insists that they can’t look at their numbers when they count since by now they should have memorized them. If anyone of the prisoners gets his number wrong, the punishment is a dozen push-ups for everyone. Still competing with Landry for dominance in the guards’ pecking order, Hellmann becomes ever more arbitrary: “I don’t like the way you count when you’re going down. I want you to count when you’re going up. Do ten more push-ups for me, will you, 5486.” The prisoners are clearly complying with orders more and more quickly. But that just reinforces the guards’ desire to demand more of them. Hellmann: “Well, that’s just great. Why don’t you sing it this time? You men don’t sing very well, it just doesn’t sound too sweet to me.” Landry: “I don’t think they’re keeping very good time. Make it nice and sweet, make it a pleasure to the ear.” 819 and 5486 continue to mock the process but, oddly, comply with the guards’ demands to perform many jumping jacks as their punishment.

The new guard, Burdan, gets into the act even more quickly than did the other guards, but he has had on-the-job training watching his two role models strut their stuff. “Oh, that was pretty! Now, that’s the way I want you to do it. 3401, come out here and do a solo, tell us what your number is!” Burdan goes beyond what his fellow guards have been doing by physically pulling prisoners out of line to sing their solos in front of the others.

Prisoner Stew-819 has become marked. He has been made to sing a solo tune, again and again, but his song is deemed never “sweet enough.” The guards banter back and forth: “He sure doesn’t sound sweet!” “No, he doesn’t sound sweet to me at all.” “Ten more.” Hellmann appreciates Burdan’s beginning to act like a guard, but he is not ready to relinquish control to him or to Landry. He asks the prisoners to recite the number of the prisoner next down in line to them. When they don’t know it, as most do not, ever more push-ups.

“5486, you sound real tired. Can’t you do any better? Let’s have five more.” Hellmann has come up with a creative new plan to teach Jerry-5486 his number in an unforgettable way: “First do five push-ups, then four jumping jacks, then eight push-ups and six jumping jacks, just so you will remember exactly what that number is, 5486.” He is becoming more cleverly inventive in designing punishments, the first signs of creative evil.

Landry has withdrawn to the far side of the Yard, apparently ceding dominance to Hellmann. As he does, Burdan moves in to fill the space, but instead of competing with Hellmann, he supports him, typically either adding to his commands or elaborating upon them. But Landry is not out of it yet. He moves back in and demands another number count. Not really satisfied with the last one, he tells the nine tired prisoners to count off now by twos, then by threes, and up and up. He is obviously not as creative as Hellmann but competitive nevertheless. 5486 is confused and made to do more and more push-ups. Hellmann interrupts, “I’d have you do it by 7s, but I know you’re not that smart, so come over and get your blankets.” Landry tries to continue: “Wait, wait, hold it. Hands against the wall.” But Hellmann will have none of that and, in a most authoritative fashion, ignores Landry’s last order and dismisses the prisoners to get sheets and blankets, make their beds, and stay in their cells until further notice. Hellmann, who has taken charge of the keys, locks them in.

THE FIRST SIGN OF REBELLION BREWING

At the end of his shift, as he is leaving the Yard, Hellmann yells out to the prisoners, “All right, gentlemen, did you enjoy our counts?” “No sir!” “Who said that?” Prisoner 8612 owns up to that remark, saying he was raised not to tell a lie. All three guards rush into Cell 2 and grab 8612, who is giving the clenched-fist salute of dissident radicals as he shouts, “All power to the people!” He is dumped into the Hole—with the distinction of being its first occupant. The guards show that they are united about one principle: they will not tolerate any dissent. Landry now follows up on Hellmann’s previous question to the prisoners. “All right, did you enjoy your count?” “Yes sir.” “Yes sir, what?” “Yes sir, Mr. Correctional Officer.” “That’s more like it.” Since no one else is willing to openly challenge their authority, the three caballeros walk down the hall in formation, as though in a military parade. Before going off to the guards’ quarters, Hellmann peers into Cell 2 to remind its occupants that “I want these beds in real apple pie order.” Prisoner 5486 later reported feeling depressed when 8612 was put into the Hole. He also felt guilty for not having done anything to intervene. But he rationalized his behavior in not wanting to sacrifice his comfort or get thrown into solitary as well by reminding himself that “it’s only an experiment.”

6

Before lights out at 10 P.M. sharp, prisoners are allowed their last toilet privilege of the night. To do so requires permission, and one by one, or two by two, they are blindfolded and led to the toilet—out the entrance to the prison and around the corridor by a circuitous route through a noisy boiler room to confuse them about both its location and their own. Later, this inefficient procedure will be streamlined as all prisoners tread this toilet route ensemble, and it might include an elevator ride for further confusion.

At first, Prisoner Tom-2093 says he needs more than the brief time allocated because he can’t urinate since he is so tense. The guards refuse, but the other prisoners unify in their insistence that he be allowed sufficient time. “It was a matter of establishing that there were certain things that we wanted,” 5486 later defiantly reported.

7 Small events like this one are what can combine to give a new collective identity to prisoners as something more than a collection of individuals trying to survive on their own. Rebel Doug-8612 feels that the guards are obviously role-playing, that their behavior is just a joke, but that they are “going overboard.” He will continue his efforts to organize the other prisoners so they will have more power. In contrast, our fair-haired-boy prisoner, Hubbie-7258, reports that “As the day goes on, I wish I was a guard.”

8 Not surprisingly, none of the guards wishes to be a prisoner.

Another rebellious prisoner, 819, showed his stuff in his letter to his family, asking them to come to Visiting Night. He signed it, “All power to the oppressed brothers, victory is inevitable. No kidding, I am as happy here as a prisoner can be!”

9 While playing cards in their quarters, the night shift guards and the warden decide on a plan for the first count of the morning shift that will distress the prisoners. Shortly after the start of their shift, the guards will stand close to the cell doors and awaken their charges with loud, shrieking whistles. This will also quickly get the new guard shift energized into their roles and disturb the sleep of the prisoners at the same time. Landry, Burdan, and Hellmann all like that plan and as they continue playing discuss how they can be better guards the following night. Hellmann thinks it is all “fun and games.” He has decided to act like “hot shit” from now on, “to play a more domineering role,” as in a fraternity hazing or in movies about prisons, like

Cool Hand Luke.

10

Burdan is in a critical position as swingman, as the guard in the middle, on this night shift. Geoff Landry started out strong but, as the night wore on, deferred to Hellmann’s creative inventions and finally gave in to his powerful style. Later, Landry will move into the role of a “good guard”—friendly toward the inmates and doing nothing to degrade them. If Burdan sides with Landry, then together they might dim Hellmann’s bright lights. But if Burdan sides with the tough guy, Landry will be odd man out and the shift will move in a sinister direction. In his retrospective diary, Burdan writes that he felt anxious when he was suddenly called at 6 P.M. that night to be on duty ASAP.

Putting on a military-style uniform made him feel silly, given the overflowing black hair on his face and head, a contrast that he worried might make prisoners laugh at him. He consciously decided not to look them in the eyes, nor smile, nor treat the scenario as a game. Compared with Hellmann and Landry, who look self-assured in the new roles, he is not. He thinks of them as “the regulars” even though they were at their jobs only a few hours before his arrival. What he enjoys most about his costume is carrying the big billy club, which conveys a sense of power and security as he wields it, rattling it against the bars of the cell doors, banging it on the Hole door, or just pounding into his hand, which becomes his routine gesture. The rap session at the end of his shift with his new buddies has made him more like his old self, less like a power-drunk guard. He does, however, give Landry a pep talk about the necessity for all of them to work as a team in order to keep the prisoners in line and not to tolerate any rebelliousness.

Shrieking Whistles at 2:30 A.M.

The morning shift comes on in the middle of the night, 2 A.M., and quits at 10 A.M. This shift consists of Andre Ceros, another long-haired, bearded young man, who is joined by Karl Vandy. Remember that Vandy had helped the day shift to transport prisoners from the County Jail to our jail, so he starts out rather tired. Like Burdan, he sports a full head of long, sleek hair. The third guard, Mike Varnish, is built like an offensive lineman, sturdy and muscular but shorter than the other two. When the warden tells them that there will be a surprise wake-up notice to announce that their shift is at work, all three are delighted to start off with such a big bang.

The prisoners are sound asleep. Some are snoring in their dark, cramped cells. Suddenly the silence is shattered. Loud whistles shriek, voices yell, “Up and at ’em.” “Wake up and get out here for the count!” “Okay, you sleeping beauties, it’s time to see if you learned how to count.” Dazed prisoners line up against the wall and count off mindlessly as the three guards alternate in coming up with new variations on count themes. The count and its attendant push-ups and jumping jacks for failures continue on and on for nearly a weary hour. Finally, the prisoners are ordered back to sleep—until reveille a few hours later. Some prisoners report that they felt the first signs of time distortion, feeling surprised, exhausted, and angry. Some later admit that they considered quitting at this point.

Guard Ceros, at first uncomfortable in his uniform, now likes the effect of wearing silver reflecting glasses. They make him feel “safely authoritative.” But the loud whistles echoing through the dark chamber scare him a bit. He feels he is too soft to be a good guard, so he tries to turn his urge to laugh into a “sadistic smile.”

11 He goes out of his way to compliment the warden on his constant suggestions for sadistic ways to enhance the count. Varnish later reported that he knew it would be tough for him to be a strong guard, and therefore he looked to the others for clues about how to behave in this unusual setting, as most of us do when we find ourselves in an alien situation. He felt that the main task of the guards was to help create an environment in which the prisoners would lose their old identities and take on new ones.

Some Initial Observations and Concerns

My notes at this time raise the following questions on which to focus our attention over the coming days and nights: Will the arbitrary cruelty of the guards continue to increase, or will it reach some equilibrium point? When they go home and reflect on what they did here, can we expect them to repent, feel somewhat ashamed of their excesses, and act more kindly? Is it possible that the verbal aggression will escalate and even turn to more physical force? Already, the boredom of tedious eight-hour guard shifts has driven the guards to entertain themselves by using the prisoners as playthings. How will they deal with this boredom as the experiment goes forward? For the prisoners, how will they deal with the boredom of living as prisoners around the clock? Will the prisoners be able to maintain some measure of dignity or rights for themselves by unifying in their opposition, or will they allow themselves to become completely subject to the guards’ demands? How long will it be before the first prisoner decides he has had too much and quits the experiment, and will that cascade into others following suit? We’ve seen very different styles between the day shift and the night shift. What will the morning shift’s style be like?

It is evident that it has taken a while for these students to take on their new roles, and with considerable hesitation and some awkwardness. There is still a clear sense that it is an experiment on prison life and not really much like an actual prison. They may never transcend that psychological barrier of feeling as though one were imprisoned in a place in which he had lost his freedom to leave at will. How could we expect that outcome in something that was so obviously an experiment, despite the mundane reality of the police arrests? In my orientation of the guards on Saturday, I had tried to initiate them into thinking of this place as a prison in its imitation of the psychological functionality of real prisons. I had described the kinds of mental sets that characterize the guard–prisoner experiences that take place in prisons, which I had learned from my contacts with our prison consultant, the formerly incarcerated Carlo Prescott, and from the summer school course we had just completed on the psychology of imprisonment. I worried that I might have given too much direction to them, which would demand behavior that they were simply following rather than gradually internalizing their new roles through their on-the-job-experiences. So far, it seemed as if the guards were rather varied in their behavior and not acting from a preplanned script. Let’s review what transpired in that earlier guard orientation.

SATURDAY’S GUARD ORIENTATION

In preparation for the experiment, our staff met with the dozen guards to discuss the purpose of the experiment, give them their assignments, and suggest means of keeping the prisoners under control without using physical punishment. Nine of the guards had been randomly assigned to the three shifts, with the other three as backup, or relief guards, available for emergency duty. After I provided an overview of why we were interested in a study of prison life, Warden David Jaffe described some of the procedures and duties of the guards, while Craig Haney and Curt Banks, in the role of psychological counselors, gave detailed information about Sunday’s arrest features and the induction of the new prisoners into our jail.

In reviewing the purpose of the experiment, I told them that I believe all prisons to be physical metaphors for the loss of freedom that all of us feel in different ways for different reasons. As social psychologists, we want to understand the psychological barriers that prisons create between people. Of course, there were limits to what could be accomplished in an experiment using only a “mock prison.” The prisoners knew they were being imprisoned for only the relatively short time of two weeks, unlike the long years most real inmates serve. They also knew that there were limits to what we could do to them in an experimental setting, unlike real prisons, where prisoners can be beaten, electrically shocked, gang-raped, and sometimes even killed. I made it clear that we couldn’t physically abuse the “prisoners” in any way.

I also made it evident that, despite these constraints, we wanted to create a psychological atmosphere that would capture some of the essential features characteristic of many prisons I had learned about recently.

“We cannot physically abuse or torture them,” I said. “We can create boredom. We can create a sense of frustration. We can create fear in them, to some degree. We can create a notion of the arbitrariness that governs their lives, which are totally controlled by us, by the system, by you, me, Jaffe. They’ll have no privacy at all, there will be constant surveillance—nothing they do will go unobserved. They will have no freedom of action. They will be able to do nothing and say nothing that we don’t permit. We’re going to take away their individuality in various ways. They’re going to be wearing uniforms, and at no time will anybody call them by name; they will have numbers and be called only by their numbers. In general, what all this should create in them is a sense of powerlessness. We have total power in the situation. They have none. The research question is, What will they do to try to gain power, to regain some degree of individuality, to gain some freedom, to gain some privacy? Will the prisoners essentially work against us to regain some of what they now have as they freely move outside the prison?”

12

I indicated to these neophyte guards that the prisoners were likely to think of this all as “fun and games” but it was up to all of us as prison staff to produce the required psychological state in the prisoners for as long as the study lasted. We would have to make them feel as though they were in prison; we should never mention this as a study or an experiment. After answering various questions from these guards-in-the-making, I outlined the way in which the three shifts would be chosen by their preferences so as to have three of them on each shift. I then made it clear that the seemingly least desirable night shift was likely to be the easiest because the prisoners would be sleeping at least half the time. “There’ll be relatively little for you to do, although you can’t sleep. You have to be there in case they plan something.” Despite my assumption that there would be little work for the night shift, that shift ended up doing the most work—and carrying out the most abusive treatment of the prisoners.

I should mention again that my initial interest was more in the prisoners and their adjustment to this prisonlike situation than it was in the guards. The guards were merely ensemble players who would help create a mind-set in the prisoners of the feeling of being imprisoned. I think that perspective came from my lower-class background, which made me identify more with prisoners than guards. It surely was shaped by my extensive personal contact with Prescott and the other former inmates I had recently gotten to know. So my orientation speech was designed to get the guards “into the mood of the joint” by outlining some of the key situational and psychological processes at work in typical prisons. Over time, it became evident to us that the behavior of the guards was as interesting as, or sometimes even more interesting than, that of the prisoners. Would we have gotten the same outcome without this orientation, had we allowed only the behavioral context and role-playing to operate? As you will see, despite this biasing guidance, the guards initially did little to enact the attitudes and behaviors that were needed to create such negative mind-sets in the prisoners. It took time for their new roles and the situational forces to operate upon them in ways that would gradually transform them into perpetrators of abuse against the prisoners—the evil that I was ultimately responsible for creating in this Stanford County Jail.

Looked at another way, these guards had no formal training in becoming guards, were told primarily to maintain law and order, not to allow prisoners to escape, and never to use physical force against the prisoners, and were given a general orientation about the negative aspects of the psychology of imprisonment. The procedure is much like many systems of inducting guards into correctional service with limited training, only that they are allowed to use whatever force is necessary under threatening circumstances. The set of rules given by the warden and the guards to the prisoners and my orientation instructions to the guards represent the contributions of the System in creating a set of initial situational conditions that would challenge the values, attitudes, and personality dispositions that these experimental participants brought into this unique setting. We will soon see how the conflict between the power of the situation and the power of the person was resolved.

| Guards |

Prisoners |

| Day Shift: 10 A.M.–6 P.M. |

Cell #1 |

| Arnett, Markus, |

3401—Glenn |

| Landry (John) |

5704—Paul |

| Night Shift: 6 P.M.–2 A.M. |

7258—Hubbie |

| Hellmann, Burdan |

Cell #2 |

| Landry (Geoff) |

819—Stewart |

| Morning Shift: 2 A.M.–10 A.M. |

1037—Rich |

| Vandy, Ceros |

8612—Doug |

| Varnish |

Cell #3 |

| Back-up Guards |

2093—Tom “Sarge” |

| Morismo, Peters |

4325—Jim |

|

5486—Jerry |