CHAPTER FOUR

Monday’s Prisoner Rebellion

MONDAY,

MONDAY,

DREARY and weary for all of us after a much too long first day and a seemingly endless night. But there go the shrill whistles again, rousing the prisoners from sleep promptly at 6

A.M. They drift out of their cells bleary-eyed, adjusting their stocking caps and smocks, untangling their ankle chains. They are a sullen lot. 5704 later told us that it was depressing to face this new day knowing he would have to go through “all the same shit again, and maybe worse.”

1

Guard Ceros is lifting up the droopy heads—especially that of 1037, who looks as though he is sleepwalking. He pushes their shoulders back to more erect positions while physically adjusting the posture of slouching inmates. He’s like a mother preparing her sleepy children for their first day at school, only a bit rougher. It is time for more rule learning and morning exercise before breakfast can be served. Vandy takes command: “Okay, we’re going to teach you these rules until you have all of them memorized.”

2 His energy is contagious, stimulating Ceros to walk up and down the line of prisoners, brandishing his billy club. Quickly losing patience, Ceros yells, “Come on, come on!” when the prisoners do not repeat the rules fast enough. Ceros smacks his club against his open palm, making the

wap, wap sound of restrained aggression.

Vandy goes through toilet instructions for several minutes and repeats them many times until the prisoners meet his standards, repeating what he has told them about how they will use the facilities, for how long, and in silence. “819 thinks it’s funny. Maybe we’ll have something special for 819.” Guard Varnish stands off to the side, not doing much at all. Ceros and Vandy switch roles. Prisoner 819 continues to smile and even laugh at the absurdity of it all. “It’s not funny, 819.”

Throughout, Guard Markus alternates with Ceros in reading the rules. Ceros: “Louder on that one! Prisoners must report all rule violations to the guards.” Prisoners are made to sing the rules, and after so many repetitions they have obviously learned all of them. Next come instructions regarding proper military style upkeep of their cots. “From now on your towels will be rolled up and placed neatly at the foot of your beds. Neatly, not thrown around, got that?” says Vandy.

Prisoner 819 starts acting up. He quits the exercises and refuses to continue. The others also stop until their buddy rejoins them. The guard asks him to continue, which he does—for the sake of his comrades.

“Nice touch, 819, now take a seat in the Hole,” orders Vandy. 819 goes into solitary but with a defiant swagger.

As he methodically paces up and down the corridor in front of the prisoners, the tall guard Karl Vandy is beginning to like the feeling of dominance.

“Okay, what kind of day is this?” Mumbled responses.

“Louder. Are you all happy?”

“Yes, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

Varnish, trying to get into the act and be cool, asks, “Are we all happy? I didn’t hear the two of you.”

“Yes, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

“4325, what kind of day is this?”

“It’s a good day, Mr. Correctional Offic—”

“No. It’s a wonderful day!”

“Yes sir, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

They begin to chant, “It’s a wonderful day, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

“4325, what kind of day is it?”

“It’s a good day.”

Vandy: “Wrong. It’s a wonderful day!”

“Yes sir. It’s a wonderful day.”

“And you, 1037?”

1037 gives his response a peppy, sarcastic intonation: “It’s a wonderful day.”

Vandy: “I think you’ll do. Okay, return to your cells and have them neat and orderly in three minutes. Then stand by the foot of your bed.” He gives instructions to Varnish about how to inspect the cells. Three minutes later, the guards enter the individual cells while the prisoners stand by their beds in military inspection style.

REBELLION BEGINS BREWING

There’s no question that the prisoners are getting frustrated by having to deal with what the guards are doing to them. Moreover, they are hungry and still tired from lack of a sound night’s rest. However, they are going along with the show and are doing a pretty good job of making their beds, but not good enough for Vandy.

“You call that neat, 8612? It’s a mess, remake it right.” With that, he rips off the blanket and sheets and throws them on the floor. 8612 reflexively lunges at him, screaming, “You can’t do that, I just made it!”

Caught off guard, Vandy pushes the prisoner off and hits him in the chest with his fist as he yells out for reinforcements, “Guards, emergency in Cell 2!”

All the guards surround 8612 and roughly throw him into the Hole, where he joins 819, who has been sitting there quietly. Our rebels begin to plot a revolution in the dark, tight confines. But they miss the chance to go to the toilet, to which the others are escorted in pairs. It soon becomes painful to hold in the urge to urinate, so they decide not to make trouble just yet, but soon. Interestingly, Guard Ceros later told us that it was difficult to maintain the guard persona when he was alone with a prisoner going to, in, or from the toilet, because there were not the external physical props of the prison setting on which to rely. He and most of the other guards reported that they acted tougher and were more demanding on those prisoner toilet runs in order to counter their tendency to ease up when off site. It was just harder to act the tough-guard role when alone with a solitary prisoner one on one. There was also a sense of shame in grown-ups like them being reduced to toilet patrol.

3

The rebel duo occupying the Hole also misses breakfast, which is served promptly at 8 A.M. al fresco in the open Yard. Some eat sitting on the floor, while others stand. They violate the “no talking rule,” by talking and discussing a hunger strike to show prisoner solidarity. They also agree that they should start to demand a lot of things to test their power, like getting their eyeglasses, meds, and books back and not doing the exercises. Previously silent prisoners, including 3401, our only Asian-American participant, now become energized in their open support.

After breakfast, 7258 and 5486 test the plan by refusing orders to return to their cells. This forces the three guards to push them into their respective cells. Ordinarily, such disobedience would have earned them Hole time, but the Hole is already overcrowded, two people being its physical limit. In the rising cacophony, I am amazed to hear prisoners from Cell 3 volunteer to clean the dishes. This gesture is in line with the generally cooperative stance of cellmate Tom-2093, but is at odds with their buddies, who are in the process of planning rebellion. Maybe they were hoping to cool the mark, to ease the rising tensions.

With the curious exception of those in Cell 3, the prisoners are careening out of control. The morning shift guard trio decides that the prisoners must consider the guards too lax, which is encouraging this mischief. They decide it is time to stiffen up. First, they institute a morning work period, which today means scrubbing down the walls and floors. Then, in the first stroke of their collective creative revenge, they take the blankets off the prisoners’ beds in Cells 1 and 2, carry them outside the building, and drag them through the underbrush until the blankets are covered with stickers or burrs. Unless prisoners don’t mind being stuck by these sharp pins, they must spend an hour or more picking out each of them if they want to use their blankets. Prisoner 5704 goes ballistic, screaming at the senseless stupidity of this chore. But that is exactly the point. Senseless, mindless arbitrary tasks are the necessary components of guard power. The guards want to punish the rebels and also to induce unquestioning conformity. After initially refusing, 5704 reconsiders when he thinks it will get him on the good side of Guard Ceros and gain him a cigarette, so he starts picking and picking out the hundreds of stickers in his blanket. The chore was all about order, control, and power—who had it and who wanted it.

Guard Ceros asks, “Nothing but the best in this prison, wouldn’t you all agree?”

Prisoners mutter various sounds of approval.

“Really fine, Mr. Correctional Officer,” replies someone in Cell 3.

Nevertheless, 8612, just released from solitary back to Cell 2, has a somewhat different answer: “Oh, fuck you, Mr. Correctional Officer.” 8612 is ordered to shut his filthy mouth.

I realize that this is the first obscenity that has been uttered in this setting. I had expected the guards to curse a lot as part of establishing the macho role, but they have not yet done so. However, Doug-8612 does not hesitate to fling obscenities around.

Guard Ceros: “It was weird to be in command. I felt like shouting that everyone was the same. Instead, I made prisoners shout at each other, ‘You guys are a bunch of assholes!’ I was in disbelief when they recited it over and over upon my command.”

4

Vandy added, “I found myself taking on the guard role. I didn’t apologize for it; in fact, I became quite a bit bossier. The prisoners were getting quite rebellious, and I wanted to punish them for breaking up our system.”

5

The next sign of rebellion comes from a small group of prisoners, Stew-819 and Paul-5704, and, for the first time, 7258, the previously docile Hubbie. Tearing the ID numbers from the front of their uniforms, they protest loudly against the unacceptable living conditions. The guards immediately retaliate by stripping each of them stark naked until their numbers are replaced. The guards retreat to their quarters with an uneasy sense of superiority, but an eerie silence falls over the Yard as they eagerly await the end of their much too long first shift on this job.

Welcome to the Rebellion, Day Shift

When the day shift arrives and suits up before their 10 A.M. duty, they discover that all is not as under control as it was when they left yesterday. The prisoners in Cell 1 have barricaded themselves in. They refuse to come out. Guard Arnett immediately takes over and requests the morning shift to stay on until this matter is resolved. His tone implies that they are somehow responsible for letting things get out of hand.

The ringleader of the revolt is Paul-5704, who got his buddies in Cell 1, Hubbie-7258 and Glenn-3401, to agree that it was time to react against the violation of the original contract they made with the authorities (me). They push their beds against the cell door, cover the door opening with blankets, and shut off the lights. Unable to push the door open, the guards vent their anger on Cell 2, which is filled with the usual top-of-the-line troublemakers, Doug-8612, Stew-819, veterans of the Hole, and Rich-1037. In a surprise counterattack, the guards rush in, grab the three cots and haul them out into the yard, while 8612 struggles furiously to resist. There are pushing and shoving and shouting all around that cell, spilling out into the Yard.

“Up against the wall!”

“Give me the handcuffs!”

“Get everything, take everything!”

819 screams wildly, “No, no, no! This is an experiment! Leave me alone! Shit, let go of me, fucker! You’re not going to take our fucking beds!”

8612: “A fucking simulation. It’s a fucking simulated experiment. It’s no prison. And fuck Dr. Zimbargo!”

Arnett, in a remarkably calm voice, intones, “When the prisoners in Cell 1 start behaving properly, your beds will be returned. You can use whatever influence you can on them to make them behave properly.”

A calmer-sounding prisoner’s voice importunes the guards, “These are our beds. You should not take them away.”

In utter bewilderment, the naked prisoner 8612 says in a plaintive voice, “They took our clothes, and they took our beds! This is unbelievable! They took our clothes, and they took our beds.” He adds, “They don’t do that in

real prisons.” Curiously, another prisoner calls back, “They do.”

6

The guards burst into laughter. 8612 thrusts his hands between the cell door bars, open palms facing upward, in a pleading gesture, an unbelieving expression on his face and a new, strange tone to his voice. Guard J. Landry tells him to get his hands off the door, but Ceros is more direct and smacks his club against the bars. 8612 pulls his hands back just in time to avoid his fingers being smashed. The guards laugh.

Now the guards move toward Cell 3 as 8612 and 1037 call out to their Cell 3 comrades to barricade themselves in. “Get your beds in front of the door!” “One horizontal and one vertical! Don’t let them in! They’ll take your beds!” “They’ve taken our beds! Oh shit!”

1037 goes over the top with his call to violent resistance: “Fight them! Resist violently! The time has come for violent revolution!”

Guard Landry returns armed with a big fire extinguisher and shoots bursts of skin-chilling carbon dioxide into Cell 2, forcing the prisoners to flee backward. “Shut up and stay away from the door!” (Ironically, this is the same extinguisher that the Human Subjects Research Committee insisted we have available in case of an emergency!)

But as the beds are pulled from Cell 3 into the corridor, the rebels in Cell 2 feel betrayed.

“Cell 3, what’s going on? We told you to barricade the doors!”

“What kind of solidarity is that? Was it the ‘sergeant’? ‘Sergeant’ (2093), if it was your fault, that’s all right because we all understand that you’re impossible.”

“But hey, Cell 1, keep your beds like that. Don’t let them in.”

The guards realize that six of them can subdue a prisoner rebellion this time, but in the future they will have to get by with only three guards against the nine prisoners, and that could add up to trouble. Never mind: Arnett formulates the divide-and-conquer psychological tactic of making Cell 3 the privileged cell and gives its members the special privileges of washing, brushing their teeth, beds and bedding returned, and water turned on in their cell.

Guard Arnett loudly announces that because Cell 3 has been behaving well, “their beds are not being torn up; they will be returned when order is restored in Cell 1.”

The guards are trying to solicit the “good prisoners” to persuade the others to behave properly. “Well, if we knew what was wrong, we could tell them!” one of the “good prisoners” exclaims.

Vandy replies, “You don’t need to know what’s wrong. You can just tell them to straighten up.”

8612 yells out, “Cell 1, we’re with ya, all three of us.” Then he makes a vague threat to the guards as they cart him off back to solitary wearing only a towel: “The unfortunate thing is, you guys think we’ve played all our cards.”

That job done, the guards take a brief time-out for a smoke and to formulate a plan of action to deal with the Cell 1 barricade.

When Rich-1037 refuses to come out of Cell 2, three guards manhandle him, throw him to the ground, handcuff his ankles, and drag him by his feet out into the Yard. He and rebel 8612 yell back and forth from the Hole to the Yard about their condition, pleading with the full prisoner contingent to sustain the rebellion. Some guards are trying to make space in the hall closet for another place in an expanded Hole in which to deposit 1037. While they move boxes around to free up some more room, they drag him back into his cell along the floor with his feet still chained together.

Guards Arnett and Landry confer and agree on a simple way to bring some order to this bedlam: Start the count. The count confers order on chaos. Even with only four prisoners in line, all at attention, the guards begin by making the prisoners call out their numbers.

“My number is 4325, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

“My number is 2093, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

The count sounds out up and down the line, consisting of the three “goodies” from Cell 3 and 7258 naked with only a towel around his waist. Remarkably, 8612 calls out his number from the Hole, but in mocking fashion.

The guards now drag 1037 into solitary by the feet, putting him in a far corner of the hall closet that has become a makeshift second Hole. Meanwhile, 8612 continues yelling for the prison superintendent: “Hey, Zimbardo, get your ass over here!” I decide not to intervene at this point but to watch the confrontation and the attempts to restore law and order.

Some interesting comments are recorded in the retrospective diaries of the prisoners (completed after the study had ended).

Paul-5704 talks about the first effects of the time distortion that is beginning to alter everyone’s thinking. “After we had barricaded ourselves in this morning, I fell asleep for a while, still exhausted from lack of a full sleep last night. When I awoke I thought it was the next morning, but it wasn’t even lunch today yet!” He fell asleep again in the afternoon, thinking it was night when he awoke, but it was only 5 P.M. Time distortion also got to 3401, who felt starved and was angry that dinner had not been served, thinking it was 9 or 10 P.M. when it was not yet 5 P.M.

Although the guards eventually crushed the rebellion and used it as justification for escalating their dominance and control over these now potentially “dangerous prisoners,” many of the prisoners felt good about having had the courage to challenge the system. 5486 remarked that his “spirits were good, guys together, ready to raise hell. We staged the ‘Jock Strap Rebellion.’ No more jokes, no jumping jacks, no playing with our heads.” He added that he was limited by what his cellmates in the “good cell” would agree to back him up on. Had he been in Cell 1 or 2, he would have “done as they did” and rebelled more violently. Our smallest, most physically fragile prisoner, Glenn-3401, the Asian-American student, seemed to have had an epiphany during the rebellion: “I suggested moving the beds against the door to keep the guards out. Although I am usually quiet, I don’t like to be pushed around like this. Having helped to organize and participate in our rebellion was important for me. I built my ego from there. I felt it was the best thing in my entire experience. Sort of asserting myself after the barricade made me more known to myself.”

7

After Lunch, Maybe an Escape

With Cell 1 still barricaded and some rebels in solitary, lunch is set for only a few. The guards have prepared a special lunch for “Good Cell 3,” for them to eat in front of their less-well-behaved fellows. Surprising us again, they refuse the meal. The guards try to persuade them just to taste the delicious meal, but even though they are hungry after their minimal oatmeal breakfast and last night’s slim dinner, the Cell 3 inmates cannot agree to act as such traitors, as “rat finks.” A strange silence pervades the Yard for the next hour. However, these Cell 3 men are totally cooperative during the work period chores, some of which include taking more stickers out of their blankets. Prisoner Rich-1037 is offered a chance to leave solitary and join the work brigade but refuses. He is coming to prefer the relative quiet in the dark. The rules say only one hour max in the Hole, but that max is being stretched to two hours now for 1037, and also for occupant 8612.

Meanwhile in Cell 1, two prisoners are quietly executing the first stage of their new escape plan. Paul-5704 will use his long fingernails, strengthened from guitar picking, to loosen the screws in the faceplate of the power outlet. Once that is accomplished, they plan to use the edge of the plate as a screwdriver to unscrew the cell door lock. One will pretend to be sick and, when the guard is taking him to the toilet, will open the main entrance door down the hall. Signaled by a whistle, the other cellmate will burst out. They will knock the guard down and run away to freedom! As in real prisons, prisoners can show remarkable creativity in fashioning weapons out of virtually anything and hatching ingenious escape plans. Time and oppression are the fathers of rebellious invention.

But as bad luck would have it, Guard John Landry, making routine rounds, turns the door handle on Cell 1, and it falls out to the ground with a resounding thud. Panic ensues. “Help!” Landry screams out. “Escape!” Arnett and Markus rush in, block the door, and then get handcuffs to chain the would-be escapees together on the floor of their cell. Of course, 8612 was one of the troublemakers, so he gets his frequent-flyer trip back into the Hole.

A Nice Count to Calm the Restless Masses

Several anxious hours have passed since the day shift reported for work. It is time to soothe the savage beasts before further trouble erupts. “Good behavior is rewarded, and bad behavior is not rewarded.” That calm, commanding voice is now clearly identified as Arnett’s. He and Landry once again join forces to line up their charges for another count. Arnett takes charge. He has emerged as the leader of the day shift. “Hands against the wall, on this wall here. Now let’s see how well everyone is learning his numbers. As before, sound your number, starting at this end.”

Sarge starts it off, setting the tone of a fast, loud response, which the other prisoners pick up with some variations. 4325 and 7258 are fast and obedient. We have not heard much from Jim-4325, a big, robust six-footer who could be a lot to handle if he decided to get physical with the guards. In contrast, Glenn-3401 and Stew-819 are always slower, evidently reluctant to comply mindlessly. Not satisfied, and imposing his own brand of control, Arnett makes them count in creative ways. They do it by threes, backward, any way he can devise that will make it unnecessarily difficult. Arnett is also demonstrating his creativity to all onlookers, as does Guard Hellmann, but Arnett doesn’t seem to take nearly as much personal pleasure in his performance as the other shift leader does. For him, this is more a job to be done efficiently.

Landry suggests having the prisoners sing their numbers; Arnett asks, “Was that popular last night? Did people like singing?” Landry: “I thought they liked it last night.” But a few prisoners respond that they don’t like to sing. Arnett: “Oh, well, you must learn to do things you don’t like; it’s part of reintegrating into regular society.”

819 complains, “People out on the streets don’t have numbers.”

Arnett responds, “People out on the street don’t have to have numbers! You have to have numbers because of your status here!”

Landry gives specific instructions about how to sing their scales: sing up a scale, like “do re mi.” All of the prisoners conform and sing the ascending scale to the best of their ability, then the descending scale, except for 819, who doesn’t attempt any scales. “819 can’t sing for a damn; let’s hear it again.” 819 starts to explain why he can’t sing. Arnett, however, clarifies the purpose of this exercise. “I didn’t ask you why you couldn’t sing, the object is for you to learn to sing.” Arnett criticizes the prisoners for their poor singing, but the weary prisoners just giggle and laugh when they make mistakes.

In contrast to his shift mates, Guard John Markus seems listless. He rarely gets involved in the main activities in the Yard. Instead, he volunteers to do off-site chores, like picking up food at the college cafeteria. His body posture gives the impression that he is not enacting the macho guard image; he slouches, shoulders down, head drooping. I ask Warden Jaffe to talk to him about being more responsive to the job for which he is getting paid. The warden takes him off the Yard into his office and chastises him.

“The guards have to know that every guard has to be what we call a ‘tough guard.’ The success of this experiment rides on the behavior of the guards to make it seem as realistic as possible.” Markus challenges him, “Real-life experience has taught me that tough, aggressive behavior is counterproductive.” Jaffe gets defensive. He starts saying that the purpose of the experiment is not to reform prisoners but to understand how prisons change people when they are faced with the situation of guards being all-powerful.

“But we are also being affected by this situation. Just putting on this guard uniform is a pretty heavy thing for me.” Jaffe becomes more reassuring; “I understand where you are coming from. We need you to act in a certain way. For the time being, we need you to play the role of ‘tough guard.’ We need you to react as you imagine the ‘pigs’ would. We’re trying to set up the stereotype guard—your individual style has been a little too soft.”

“Okay, I will try to adjust somewhat.”

“Good, I knew we could count on you.”

8

Meanwhile, 8612 and 1037 remain in solitary. However, now they are yelling out complaints about violations of the rules. No one is paying attention. Each of them separately says he needs to see a doctor. 8612 says he is feeling ill, feeling strange. He mentions a weird sensation of his stocking cap still being on his head when he knows it is not there. His demand to see the warden will be granted later in the day.

At four o’clock, beds are returned to good Cell 3, as the guards’ attention focuses on the prisoners in the still rebellious Cell 1. The night shift guards are asked to come in early, and together with the day shift they storm the cell, shooting the fire extinguisher at the door opening to keep the prisoners at bay. They strip the three prisoners naked, take away their beds, and threaten to deprive them of dinner if they show any further disobedience. Already hungry from missing lunch, the prisoners melt into a sullen, quiet blob.

The Stanford County Jail Prisoners’ Grievance Committee

Realizing that the situation is becoming volatile, I have the warden announce over the loudspeaker that prisoners should elect three members to the newly formed “Stanford County Jail Prisoners’ Grievance Committee,” who will meet with Superintendent Zimbardo as soon as they agree on what grievances they want to have addressed and rectified. We later learn from a letter that Paul-5704 sent to his girlfriend that he was proud to be nominated by his comrades to head this committee. This is a remarkable statement, showing how the prisoners had lost their broad time perspectives and were living “in the moment.”

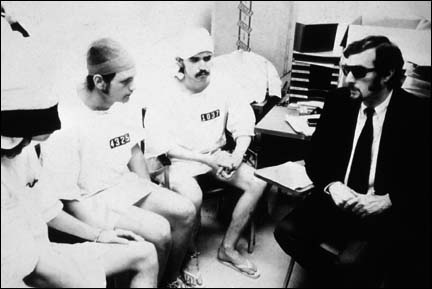

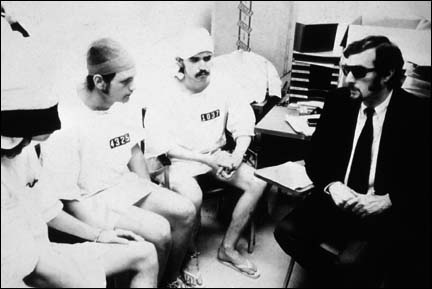

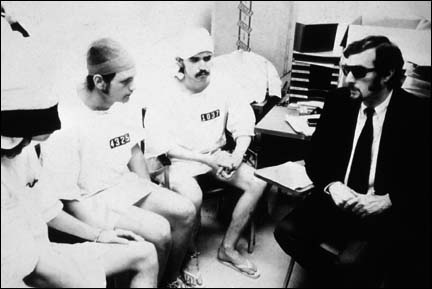

The Grievance Committee, consisting of elected members, Paul-5704, Jim-4325, and Rich-1037, tell me that their contract has been violated in many ways. Their prepared list includes that: the guards are being both physically and verbally abusive; there is an unnecessary level of harassment; the food is not adequate; they want to have their books, glasses, and various pills and meds returned; they want more than one Visiting Night; and some of them want religious services. They argue that all of these conditions justified their need to rebel openly as they had all day long.

Behind my silver reflecting sunglasses, I slip into the superintendent role automatically. I start out by saying I am sure we can resolve any disagreements amicably, to our mutual satisfaction. I note that this Grievance Committee is a fine first step in that direction. I am willing to work directly with them as long as they represent the will of all the others. “But you have to understand that a lot of the guards’ hassling and physical actions have been induced by your bad behavior. You have brought it upon yourselves by disrupting our planned schedules and by creating panic among the guards, who are new to this line of work. They took away many of your privileges rather than becoming more physically abusive to the rebellious prisoners.” The Grievance Committee members nod knowingly. “I promise to take this grievance list to my staff tonight and to change as many negative conditions as possible, and to institute some of the positive things you have suggested. I will bring a prison chaplain down tomorrow and have a second Visiting Night this week, for starters.”

“That’s great, thanks,” says the head prisoner, Paul-5704, and the others nod in agreement that progress is being made toward a more civil prison.

We stand and shake hands, and they leave pacified. I hope that they will tell their buddies to cool it from now on, so we can avoid such confrontations.

PRISONER 8612 BEGINS A MELTDOWN

Doug-8612 is not in a cooperative mood. He is not buying the goodwill message of the grievance guys. More insubordination earns him more Hole time, with his hands cuffed continuously. He says he is feeling sick and demands to see the warden. A while later, Warden Jaffe meets with him in his office and listens to the prisoner complain about the arbitrary and “sadistic” behavior of the guards. Jaffe tells him that his behavior is triggering the guards’ reactions. If he would be more cooperative, Jaffe would see to it that the guards would lighten up on him. 8612 says that unless that happens soon, he wants out. Jaffe is also concerned about his medical complaints and asks if he wants to see a doctor, to which 8612 demurs for now. The prisoner is escorted back to his cell, from which he yells back and forth to comrade Rich-1037, who is still sitting in solitary complaining about the intolerable conditions and also wanting to see a doctor.

Although seemingly comforted by his exchange with the warden, Prisoner 8612 goes off screaming in rage, insisting on seeing “the fucking Dr. Zimbardo, Superintendent.” I agree to see him immediately.

Our Prison Consultant Mocks the Mock Prisoner

That afternoon, I had arranged for the first visit to the prison of my consultant Carlo Prescott, who had helped me design many of the features in the experiment to simulate a functional equivalent of imprisonment in a real jail. Carlo had recently been paroled from San Quentin State Prison after serving seventeen years there, as well as time served at Folsom and Vacaville Prisons, mostly for convictions on armed robbery felonies. I had met him a few months before during one of the course projects that my social psychology students organized around the theme of individuals in institutional settings. Carlo had been invited by one of the students to give the class an insider’s view of the realities of prison life.

Carlo was only four months out of prison and filled with anger at the injustice of the prison system. He railed against American capitalism, racism, black Uncle Toms who do the Man’s work against Brothers, warmongers, and much more. But he was remarkably perceptive and insightful about social interactions, as well as exceptionally eloquent, with a resonant baritone voice and seamless, nonstop delivery. I was intrigued by this man’s views, especially since we were about the same age—me thirty-eight, him forty—and both of us had grown up in an East or West coast ghetto. But while I was going to college, Carlo was going to jail. We became fast friends. I became his confidant, patient listener to his extended monologues, psychological counselor, and “booking agent” for jobs and lectures. His first job was to co-teach with me a new summer school course at Stanford University on the psychology of imprisonment. Carlo not only told the class intimate details of his personal prison experiences, he arranged for other formerly incarcerated men and women to share theirs. We added prison guards, prison lawyers, and others knowledgeable about the American prison system. That experience and intense mentoring by Carlo helped to infuse our little experiment with a kind of situational savvy never before seen in any comparable social science research.

It is about 7 P.M. when Carlo and I watch one of the counts on the TV monitor that is recording the day’s special events. Then we retreat to my superintendent’s office to discuss how things are going and how I should handle tomorrow’s Visiting Night. Suddenly, Warden Jaffe bursts in to report that 8612 is really distraught, wants out, and insists on seeing me. Jaffe can’t tell whether 8612 is just faking it to get released and then to make some trouble for us, or if he is genuinely feeling ill. He insists that it is my call and not his to make.

“Sure, bring him in so I can assess the problem,” I say.

A sullen, defiant, angry, and confused young man enters the office. “What seems to be the trouble, young man?”

“I can’t take it anymore, the guards are hassling me, they are picking on me, putting me in the Hole all the time, and—”

“Well, from what I have seen, and I have seen it all, you have brought this all on yourself; you are the most rebellious, insubordinate prisoner in the whole prison.”

“I don’t care, you have all violated the contract, I didn’t expect to get treated like this, you—”

9

“Stop right there, punk!” Carlo lashes out against 8612 with a vengeance. “You can’t take what? Push-ups, jumping’ jacks, guards calling you names and yelling at you? Is that what you mean by ‘hassling’? Don’t interrupt me. And you’re crying about being put in that closet for a few hours? Let me straighten you out, white boy. You would not last a day at San Quentin. We would all smell your fear and weakness. The guards would be banging you upside your head, and before they put you in their real solitary concrete barren pit that I endured for weeks at a time, they’d throw you to us. Snuffy, or some other bad gang boss, would’ve bought you for two, maybe three packs of cigarettes, and your ass would be bleeding bright red, white, and blue. And that would be just the beginning of turning you into a sissy.”

8612 is frozen by the fury of Carlo’s harangue. I need to rescue him because I can sense that Carlo is about to explode. Seeing our prisonlike setting has brought to his mind years of torment from which Carlo is but a few months away.

“Carlo, thanks for providing this reality check. But I need to know some things from this prisoner before we can proceed properly. 8612, you realize that I have the power to get the guards not to hassle you, if you choose to stay and cooperate. Do you need the money—the rest of which you will forfeit by quitting early?”

“Yeah, sure, but—”

“Okay, then here’s the deal, no more guards hassling you, you stay and earn your money, and in return all you have to do is cooperate from time to time, sharing a little information with me from time to time that might be helpful to me in running this prison.”

“I don’t know about that . . .”

“Look, think over my offer, and if, later on, after a good dinner, you still want to leave, then that will be fine, and you will be paid for time you have served. However, if you choose to continue, make all the money, not be hassled, and cooperate with me, then we can put the first day’s problems behind us and start over. Agreed?”

“Maybe, but—”

“No need to decide either way right now, reflect on my offer and decide later tonight, okay?”

As 8612 quietly utters, “Well, all right,” I escort him out to the warden’s next-door office to be returned to the Yard. I tell Jaffe that he is still deciding about staying and will make his decision later on.

I had thought up the Faustian bargain on the spot. I had acted like an evil prison administrator, not the good-hearted professor I like to think I am. As superintendent, I do not want 8612 to leave, because it might have a negative impact on the other inmates and because I think we might be able to get him to be more cooperative if we have guards back off their abusive behaviors toward him. But I have invited 8612, the rebel leader, to be a “snitch,” an informer, sharing information with me in return for special privileges. In the Prisoner Code, a snitch is the lowest form of animal life and is often kept in solitary by the authorities because if his informer role became known, he would be murdered. Later, Carlo and I retreat to Ricky’s restaurant, where I try to put this ugly image behind me for a short time while enjoying Carlo’s new stories over a plate of lasagna.

The Prisoner Tells Everyone That No One Can Quit

Back in the Yard, Guards Arnett and J. Landry have the prisoners lined up against the wall doing yet another count before the end of their extended day shift. Once more, Stew-819 is being ridiculed by the guards for being so listless in joining his peers, who are calling out in unison, “Thank you, Mr. Correctional Officer, for a fine day!”

The prison entrance door squeaks as it opens. The line of prisoners all look down the hall to see 8612 returning from his meeting with the prison authorities. He announced to them before seeing me that it was his bon voyage meeting. He was quitting, and there was nothing they could do to make him stay any longer. Doug-8612 now pushes his way through the line of his friends into Cell 2, throwing himself on his cot.

“8612, out here against the wall,” Arnett orders.

“Fuck you,” he replies defiantly.

“Against the wall, 8612.”

“Fuck you!” replies 8612.

Arnett: “Somebody help him!”

J. Landry asks Arnett, “Do you have the key to the handcuffs, sir?”

Still in his cell, 8612 yells out, “If I gotta be in here, I’m not going to put up with any of your shit.” As he saunters out into the Yard, with half the prisoners lined up on either side of Cell 2, Doug-8612 offers them a new terrible reality: “I mean, you know, really. I mean, I couldn’t get out! I spent all this time talking to doctors and lawyers and . . .”

His voice trails off, and it is not clear what this means. The other prisoners are giggling at him. Standing in front of the other prisoners, defying orders to stand against the wall, 8612 delivers an uppercut to his buddies. He continues to rant in his high-pitched, whiny voice: “I couldn’t get out! They wouldn’t let me out! You can’t get out of here!”

The inmates’ initial giggles are replaced by nervous laughter. The guards ignore 8612 as they continue trying to discover where the keys to the handcuffs are, assuming they will handcuff 8612 and stuff him back in the Hole if he keeps this up.

One prisoner asks 8612, “You mean you couldn’t break the contract?”

Another prisoner inquires desperately, but not of anyone in particular, “Can I cancel my contract?”

Arnett toughens up: “No talking on the line. 8612 will be around later for you all to talk with.”

This revelation from one of their respected leaders is a powerful blow to the prisoners’ resolve and defiance. Glenn-3401 reported on the impact of 8612’s assertion: “He said you can’t get out. You felt like you were really a prisoner. Maybe you were a prisoner in Zimbardo’s experiment and maybe you were getting paid for it, but damn it, you were a prisoner. You were really a prisoner.”

10

He begins to fantasize some worst-case scenarios: “The thought that we had signed our lives away for two weeks, body and soul, was exceptionally frightening. The actual belief that ‘we are really prisoners’ was real—one couldn’t escape without truly drastic action followed by a series of unknown consequences. Would the Palo Alto Police try to pick us up again? Would we get paid? How do I get my wallet back?”

11

Rich-1037, who had been a problem for the guards all day long, was also stunned by this new realization. He later reported, “I was told that I couldn’t quit. At that point, I felt it was really a prison. There’s no way I can describe how I felt at that moment. I felt totally helpless. More helpless than I have ever felt before.”

12

It was evident to me that 8612 had trapped himself in multiple dilemmas. He was caught between wanting to be the tough-guy rebel leader but not wanting to deal with the guards’ hassling, wanting to stay and earn the money he needed but not wanting to be my informer. He was probably planning to become a double agent, lying to me or misleading me about prisoner activities, but not sure of his ability to carry off that deception. He should have immediately refused my offer to trade up for some comfort by becoming the official “snitch,” but he did not. At that moment, if he had insisted on being released, I would have had to allow him that option. Again, maybe he was too shamed by Carlo’s taunting him to yield readily in front of him. All of these were possible mind games that he resolved by insisting to the others that it was our official decision not to release him, putting the blame on the system.

Nothing could have had a more transformative impact on the prisoners than the sudden news that in this experiment they had lost their liberty to quit on demand, lost their power to walk out at will. At that moment, the Stanford Prison Experiment was changed into the Stanford Prison, not by any top-down formal declarations by the staff but by this bottom-up declaration from one of the prisoners themselves. Just as the prisoner rebellion changed the way the guards began to think about the prisoners as dangerous, this prisoner’s assertion about no one being allowed to quit changed the way all the mock prisoners felt about their new status as helpless prisoners.

WE’RE BACK, IT’S NIGHT SHIFT TIME

As if things were not bad enough for the prisoners, it is now night shift time, once again. Hellmann and Burdan have been pacing the Yard waiting for the day shift to move out. They are wielding their billy clubs, yelling something into Cell 2, threatening 8612, insisting that a prisoner get back from the door, and pointing the fire extinguisher at the cell, shouting to ask whether they want more of this cool carbon dioxide spray in their faces.

A prisoner asks Guard Geoff Landry: “Mr. Correctional Officer, I have a request. It’s somebody’s birthday tonight. Can we sing ‘Happy Birthday’?”

Before Landry can answer, Hellmann replies from the background, “We’ll sing ‘Happy Birthday’ at lineup. Now it is dinner time, three at a time.” The prisoners now sit around a table laid out in the middle of the yard to eat their skimpy dinner. No talking allowed.

Reviewing the tapes of this shift, I see a prisoner being brought in through the main doors by Burdan. The prisoner, who had just attempted to escape, stands at attention in the center of the hallway just beyond the dinner table. He is blindfolded. Landry asks the prisoner how he removed the lock on the door. He refuses to spill the beans. When the blindfold is taken off the escapee, Geoff warns menacingly, “If we see your hands near that lock, 8612, we’ll have something really good for you.” It was Doug-8612 who tried the escape plan! Landry pushes him back into his cell, where 8612 begins to scream obscenities again, louder than before, and a stream of ‘Fuck yous’ floods the Yard. Hellmann says wearily into Cell 2, “8612, your game is getting very old. Very old. It’s not even amusing anymore.”

The guards rush to the dinner table to stop 5486 from conferring with his Cell mates, who have been forbidden to communicate. Geoff Landry shouts at 5486, “Hey, hey! We can’t deprive you of a meal, but we can take the rest of it away. You’ve had something. The warden says we can’t deprive you of meals, but you’ve already had a meal, at least part of it. So we can take the rest away.” He then makes a general pronouncement to everyone: “You guys seem to have forgotten about all of the privileges we can give you.” He reminds them of the visiting hours tomorrow, which, of course, could be canceled if there is a lockdown. Some prisoners who are still eating say that they have not forgotten about Tuesday’s seven o’clock visiting hours and are looking forward to them.

Geoff Landry insists that 8612 put back on his stocking cap, which he had taken off during dinner. “We wouldn’t want you dropping anything out of your hair into your meal and getting sick on it.”

8612 responds strangely, as though he is losing contact with reality: “I can’t put it on my head, it’s too tight. I’ll get a headache. What? I know that’s really weird. That’s why I’m trying to get out of here . . . they keep saying ‘No, you won’t get a headache,’ but I know I will get a headache.”

Now it becomes Rich-1037’s turn to be despondent and detached. He is looking glassy-eyed, speaking only in a slow monotone. Lying on the floor of his cell, he keeps coughing, insists on seeing the superintendent. (I see him when I return from my dinner, give him some cough drops, and tell him that he can leave if he feels he can’t take it anymore but that things will go better if he does not spend so much time and energy rebelling. He reports feeling better and promises to try his best.)

The guards next turn their attention on Paul-5704, who is now being more assertive, as if to stand in for former rebel leader Doug-8612. “You don’t look too happy, 5704,” Landry says, as Hellmann starts running his club against the bars of the cell door, making a loud clanging sound. Burdan adds, “You think they’d like that [the loud bar clanging] after lights out, maybe tonight?”

5704 attempts a joke, but the guards are not laughing, although some of the prisoners are. Landry says, “Oh, that’s good, that’s real good. Keep it up, really. We’re really getting entertained now. I haven’t heard this type of kid stuff in about ten years.”

The guards, standing tall, all in a row, stare at 8612, who is eating slowly and by himself. With one hand on their hips and the other swinging their billy clubs menacingly, the guards display a united front. “We have a bunch of resisters, revolutionaries, here!” exclaims Geoff Landry.

8612 then bolts up from the dinner table and races across to the rear wall, where he rips down the black scrim covering the video camera. The guards grab him and drag him back into the Hole yet again. He says sarcastically, “Sorry, guys!”

One of them responds, “You’re sorry, huh. We’ll have something for you later that you will be sorry for.”

When Hellmann and Burdan both start banging on the door of the Hole with their billy clubs, 8612 starts screaming that it is deafening and is making his headache worse.

Doug-8612 yells out, “Fuckin’ don’t do that man, it hurts my ears!”

Burdan: “Maybe you’ll think about that before you want to do something that gets you into the Hole next time, 8612.”

8612 answers, “Nah, you can just fuck off, buddy! Next time the doors go down, I mean it!” (He is threatening to tear down the door to his cell, the entrance door, and perhaps he means the wall where the observation camera is located.)

A prisoner asks if they’ll be having a movie tonight, as they had expected to get when the original details of the prison were described to them. A guard replies, “I don’t know if we’ll ever have a movie!”

The guards openly discuss the consequences of damaging prison property, and Hellmann grabs a copy of the prison rules, reading off the rule about damaging prison property. As he leans against Cell 1’s doorframe and twirls his billy club, he seems to be inhaling confidence and dominance moment by moment. Instead of movie time, he will give them either work or R&R time, Hellmann tells his buddies.

Hellmann: “Okay, let’s have your attention, please. We have some fun lined up for everyone tonight. Cell 3, you’re on rest and recreation, you can do what you please because you washed your dishes and did your chores well. Cell 2, you’ve still got a little bit of work to do. And Cell 1, we’ve got a great blanket for you to pick all the stickers out of. Okay, bring them on in here, Officer, let’s let them see, they gonna do just fine for Cell 1 to work on tonight if they want to sleep on a blanket without stickers.”

Landry hands Hellman some blankets coated with a new collection of stickers. “Oh, isn’t that a beauty?” He continues his monologue: “Just look at that blanket, ladies and gentleman! Look at that blanket! Isn’t that a masterpiece? I want you to take each and every one of those stickers out of that blanket, because that’s what you’re gonna have to sleep on.” A prisoner tells him, “We’ll just sleep on the floor,” to which Landry replies simply, “Suit yourself, suit yourself.”

It is interesting to see how Geoff Landry vacillates between the tough-guard and good-guard roles. He still has not relinquished control to Hellmann, to whose dominance he may aspire at some level, while feeling greater sympathy for the prisoners than Hellmann seems capable of. (In a later interview, the thoughtful prisoner Jim-4325 describes Hellmann as one of the bad guards, nicknaming him “John Wayne.” He describes the Landry brothers as two of the “good guards,” while most other prisoners agree that Geoff Landry was more often good than bad as a guard.)

A prisoner in Cell 3 asks whether it would be possible for them to get some books to read. Hellmann suggests giving them all “a couple of copies of the rules” as their bedtime reading material. Now it is time for another count. “Okay, there’ll be no goofing off tonight, remember? Let’s start at 2093, and let’s count off, just so we can keep in practice,” he says.

Burdan jumps on the bandwagon, walks right up in the prisoners’ faces, and says, “We didn’t teach you to count that way. Loud, clear, and fast! 5704, you are sure slow enough! You can start off with the jumping jacks.”

The guards’ punishment is becoming indiscriminate; they’re no longer punishing prisoners for any specific reason. 5704 is having none of that: “I’m not gonna do it!”

Burdan forces him into it, so he goes down, but not far enough, apparently. “Down, man, down!” pushing him down by pressing on his back with his billy club.

“Don’t push, man.”

“What do you mean, ‘Don’t push’?” in a ridiculing tone.

“That’s what I said, don’t push!”

“Just go on now and do your push-ups,” Burdan orders. “Now get back in line.”

Burdan is decidedly much more vocal and involved than he was before, but Hellmann is still clearly the “alpha male.” However, when Burdan and Hellmann become the dynamic duo, suddenly Geoff Landry recedes into the background or is not on the Yard scene at all.

Even 2093, the best prisoner, “Sarge,” is forced to do push-ups and jumping jacks for no apparent reason. “Oh, that’s nice! See how he does those? He’s got a lot of energy tonight,” says Hellmann. Then he turns on 3401: “Are you smiling? What are you smiling about?” His sidekick, Burdan, chimes in, “Are you smiling, 3401? You think this is funny? You wanna sleep tonight?”

“I don’t want to see anyone smiling! This is no locker room here. If I see one person smile it’s going to be jumping jacks for everyone for a long time!” Hellmann assures them.

Picking up on the prisoners’ need to lighten their grim surroundings, Hellmann tells Burdan a joke for the benefit of the grim prisoners: “Officer, did you hear the one about the dog with no legs? Every night, his owner would take him out for a drag.” He and Burdan laugh but note that the prisoners do not laugh. Burdan chides him, “They don’t like your joke, Officer.”

“Did you like my joke, 5486?”

Jerry-5486 prisoner answers truthfully, “No.”

“Come out here and do ten push-ups for not liking my joke. And do five more for smiling, Fifteen in all.”

Hellmann is on a roll. He makes all the prisoners face the wall; then, when they turn around, he shows them the “one-armed pencil salesman.” He puts one hand down his pants and puts his finger at his crotch, pushing out his pants as if he had an erection. The prisoners are told not to laugh. Some do laugh and are then forced do push-ups or sit-ups. 3401 says he didn’t think it was funny, but he has to do push-ups for being honest. Next comes singing their numbers. Hellmann asks Sarge-2093 if that sounded like singing.

“It sounded like singing to me, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

Hellmann makes him do push-ups for disagreeing with his judgment.

Unexpectedly, Sarge asks, “May I do more, sir?”

“You can do ten if you like.”

Then Sarge challenges him in an even more dramatic way: “Shall I do them until I drop?”

“Sure, whatever.” Hellmann and Burdan are unsure how to react to this taunt, but the prisoners look at one another in dismay, knowing that Sarge may set new criteria for self-inflicted punishment that will then be imposed on them. He is becoming a sick joke to them all.

When next the prisoners are asked to count off in a complicated order, Burdan adds mockingly, “That shouldn’t be so hard for boys with so much education!” In a sense, he is picking up on the current conservative ridicule of educated college people as “effete intellectuals snobs,” even though, of course, he is a college student himself.

The prisoners are asked if they need their blankets and beds. All say they do. “And what,” Hellmann asks, “did you boys do to deserve beds and blankets?” “We took the foxtails out of our blankets,” says one of them. He tells them to never say “foxtails.” They should call them “stickers.” Here is a simple instance of power determining language use, which, in turn, creates reality. Once the prisoner calls them “stickers,” Burdan says that they should get their pillows and blankets. Hellmann comes back with blankets and pillows under his arms. He then hands them out to everyone except Prisoner 5704. He asks him why it took him so long to get to work. “Do you feel like having a pillow? Why should I give you a pillow if you didn’t feel like working?” “Good karma,” answers 5704, feeling a bit playful.

“I’ll ask you again, why should I give you a pillow?”

“Because I’m asking you to, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

“But you didn’t get to work until ten minutes after everyone else did,” says Hellmann. He adds, “See to it that in the future you do work when you are told.” Despite this misbehavior, Hellmann finally relents and gives him the pillow.

Not to be totally upstaged by Hellmann, Burdan tells 5704, “Thank him real sweet.”

“Thank you.”

“Say it again. Say, ‘Bless you, Mr. Correctional Officer.’” The sarcasm seeps through heavily.

Hellmann successfully isolates 5704 from his revolutionary comrades by making him beg for a pillow. Simple self-interest is starting to win out over prisoner solidarity.

Happy Birthday, Prisoner 5704

Prisoner Jerry-5486 reminds the guards of his request to sing “Happy Birthday” to 5704, which is a curious request at this point given that the prisoners are so tired and the guards are about to let them return to their cells and to sleep. Perhaps it is a measure of their connection with normal rituals in the outside world or a small way to normalize what is rapidly approaching Abnormal.

Burdan tells Hellmann, “We have a point of discussion from Prisoner 5486, Officer; he wants to do the ‘Happy Birthday’ song.” Hellmann is upset when the birthday song is intended for 5704. “It’s your birthday, and you didn’t work!”

The prisoner replies that he shouldn’t have to work on his birthday. The guards go down the line and ask each one to say aloud whether he does or does not want to sing the birthday song. Each agrees that it is right to sing the birthday song to 5704 tonight. Prisoner Hubbie-7258 is then ordered to lead the others in singing “Happy Birthday”—the only pleasant sound in this place all day and night. The first time through, there is a mixture of ways in which the recipient is addressed—some sing happy birthday to “comrade,” others to “5704.” As soon as this happens, Hellmann and Burdan both scream at them.

Burdan reminds them, “This gentleman’s name is 5704. Now take it from the top.”

Hellmann compliments 7258 for his singing: “You give them a swing tempo, and then you sing it straight.” He says that about cut-time music, showing off a bit of his musical knowledge. But he then requests they sing the song again in a more familiar style, and they do. But their performance is not good enough, so again they are told, “Let’s have a little enthusiasm! A boy’s birthday only happens once a year.” This prisoner-initiated break in routine to share some positive feelings among themselves is turned into another occasion of learning routinized dominance and submission.

The Final Breakdown and Release of 8612

After lights out, and after Doug-8612 is finally turned out of solitary for the nth time, he goes ballistic: “I mean, Jesus Christ, I’m burning up inside! Don’t you know?”

The prisoner is screaming his angry confusion and torment to the warden during his second visit with Jaffe. “I want to get out! This is all fucked up inside! I can’t stand another night! I just can’t take it anymore! I gotta have a lawyer! Do I have a right to ask for a lawyer? Contact my mother!”

Trying to remind himself that this is just an experiment, he continues raving, “You’re messing up my head, man, my head! This is an experiment; that contract is not serfdom! You have no right to fuck with my head!”

He threatens to do anything necessary to get out, even to slit his wrists! “I’ll do anything to get out! I’ll wreck your cameras, and I’ll hurt the guards!”

The warden tries his best to comfort him, but 8612 is having none of it; he cries and screams louder and louder. Jaffe assures 8612 that as soon as he can contact one of the psychological counselors his request will be seriously considered.

A short while later, Craig Haney returns from his late dinner and, after listening to Jaffe’s tape recording of this dramatic scene, he interviews 8612 to determine whether he should be released immediately based on such severe emotional distress. At the time, we were all uncertain about the legitimacy of 8612’s reactions; he might be just playacting. A check of his background information revealed that he was also a leading antiwar activist at his university, just last year. How could he really be “breaking down” in only thirty-six hours?

8612 was indeed confused, as he revealed to us later: “I couldn’t decide whether the prison experience had really freaked me out, or whether I had induced those reactions [purposefully].”

The conflict that Craig Haney was experiencing over being forced to make this decision on his own, while I was out having dinner, is vividly expressed in his later analysis:

Although in retrospect it seems like an easy call, at the time it was a daunting one. I was a 2nd year graduate student, we had invested a great deal of time, effort, and money into this project, and I knew that the early release of a participant would compromise the experimental design we had carefully drawn up and implemented. As experimenters, none of us had predicted an event like this, and of course, we had devised no contingency plan to cover it. On the other hand, it was obvious that this young man was more disturbed by his brief experience in the Stanford Prison than any of us had expected any of the participants to be even by the end of 2 weeks. So I decided to release Prisoner 8612, going with the ethical/humanitarian decision over the experimental one.

13

Craig contacted 8612’s girlfriend, who quickly came by and collected him and his belongings. Craig reminded the two of them that if this distress continued, he could visit Student Health in the morning because we had arranged for some of its staff to help deal with any such reactions.

Fortunately, Craig made the right decision based on both humane considerations and legal ones. It was also the right decision considering the probable negative effect on the staff and inmates of keeping 8612 imprisoned in his state of emotional disarray. However, when Craig later informed Curt and me about his decision to release 8612, we were skeptical and thought that he had been taken in, conned by a good acting job. However, after a long discussion of all the evidence, we agreed that he had done the right thing. But then we had to explain why this extreme reaction had occurred so suddenly, almost at the very start of our two-week adventure. Even though personality tests had revealed no hint of mental instability, we persuaded ourselves that the emotional distress 8612 revealed was the product of his overly sensitive personality and his overreaction to our simulated prison conditions. Together Craig, Curt, and I engaged in a bit of “groupthink,” advancing the rationalization that there must have been a flaw in our selection process that had allowed such a “damaged” person to slip by our screening—while ignoring the other possibility that the situational forces operating in this prison simulation had become overwhelming for him.

Consider, for a moment, the meaning of that judgment. Here we were in the midst of a study designed to demonstrate the power of situational forces over dispositional tendencies, yet we were making a dispositional attribution!

In retrospect, Craig expressed the fallacy in our thinking aptly: “It was only later that we appreciated this obvious irony, that we had ‘dispositionally explained’ the first truly unexpected and extraordinary demonstration of situational power in our study by resorting to precisely the kind of thinking we had designed the study to challenge and critique.”

14

Confusion remained about 8612’s ulterior motives. On the one hand, we wondered, was he really out of control, suffering from an extreme stress reaction, and so of course had to be released? Alternatively, had he started out by pretending to be “crazy,” knowing that if he did a good job, we would have to release him? It might be that, in spite of himself, he had ended up temporarily “crazed” by his over-the-top method acting. In a later report, 8612 complicates any simple understanding of his reactions: “I left when I should have stayed. That was very bad. The revolution isn’t going to be fun, and I must see that. I should have stayed because it helps the fascists knowing that [revolutionary] leaders will desert when things get rough, that they are just manipulators. And I should have fought for what was right, and not thought of my interests.”

15

Shortly after 8612 was terminated, one of the guards overheard the prisoners in Cell 2 discussing a plot in which Doug would return the next day with a band of his buddies to trash our prison and liberate the prisoners. It sounded to me like a far-fetched rumor until a guard reported seeing 8612 sneaking around the hallways of the Psychology Department the next morning. I ordered the guards to capture him and return him to the prison since he had probably been released under false pretenses: not sick, just tricking us. Now I knew that I had to prepare for an all-out assault on my prison. How could we avert a major violent confrontation? What could we do to keep our prison functioning—and oh, yes, our experiment also continuing?