CHAPTER SEVEN

The Power to Parole

TECHNICALLY SPEAKING, OUR Stanford Prison was more like a county jail filled with a group of adolescents who were being held in pretrial detention following their Sunday-morning mass arrests by the Palo Alto City Police. Obviously, no trial date had yet been set for any of these role-playing felons, and none of them had legal representation. Nevertheless, following the advice of the prison chaplain, Father McDermott, a mother of one of the prisoners was going about securing counsel for her son. After a full staff meeting with Warden David Jaffe and the “psychological counselors,” the graduate assistants Craig Haney and Curt Banks, we decide to include a Parole Board hearing even though in fact that would not have occurred at this early stage in the criminal justice process.

This would provide an opportunity to observe each prisoner deal with an unexpected opportunity to be released from his imprisonment. Until now, each prisoner had appeared only as a single actor among an ensemble of players. By holding the hearing in a room outside the prison setting, the prisoners would get some respite from their oppressively narrow confines in the basement level. They might feel freer to express their attitudes and feelings in this new environment, which would include some personnel not directly connected with the prison staff. The procedure also added to the formality of our prison experience. The Parole Board hearing, like Visiting Nights, the prison chaplain’s visit, and the anticipated visit by a public defender, lent credibility to the prison experience. Finally, I wanted to see how our prison consultant, Carlo Prescott, would enact his role as head of the Stanford County Jail Parole Board. As I said, Carlo had failed many parole board hearings in the past seventeen years and only recently had been granted lifetime parole for “good time served” on his armed robbery convictions. Would he be compassionate and side with the prisoners’ requests, as someone who had been in their place pleading for parole?

The Parole Board hearings were held on the first floor of Stanford’s Psychology Department, in my laboratory, a carpeted, large room that included provisions for hidden videotaping and observation from behind a specially designed one-way window. The four members of the Board sat around a six-sided table. Carlo sat at the head place, next to Craig Haney, and on his other side sat a male graduate student and a female secretary, both of whom had little prior knowledge of our study and were helping us out as a favor. Curt Banks would serve as sergeant-at-arms to transfer each applicant from the guard command to the parole-hearing command. I would be videotaping the proceedings from the adjacent room.

Of the remaining eight prisoners on Wednesday morning, after 8612’s release, four had been deemed potentially eligible for parole by the staff, based on generally good behavior. They had been given the opportunity to request a hearing of their case and had written formal requests explaining why they thought they deserved parole at this time. Some of the others would have a hearing another day. However, the guards insisted that Prisoner 416 not be granted such opportunity because of his persistent violation of Rule 2, “Prisoners must eat at mealtimes and only at mealtimes.”

A CHANCE TO REGAIN FREEDOM

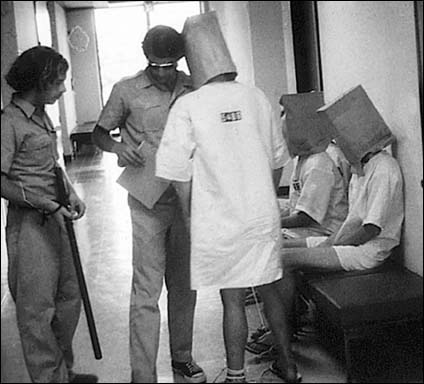

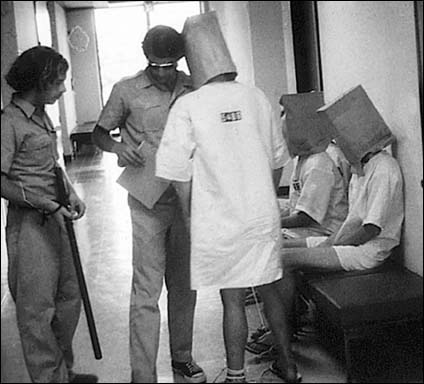

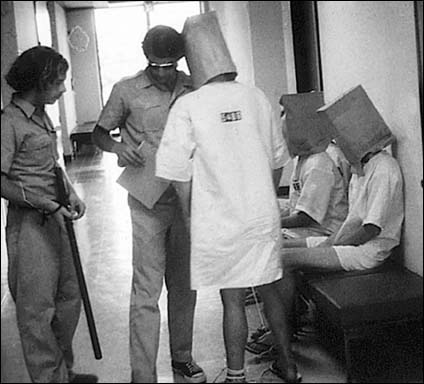

The day shift guards line up this band of four prisoners in the Yard, as was done routinely during each night’s last toilet run. The chain upon one prisoner’s leg is attached to that of the next, and large paper bags are put over their heads so they will not know how they got from the jail yard to the parole setting or where in the building it is located. They are seated on a bench in the hall outside the parole room. Their leg chains are removed, but they sit still handcuffed and bagged until Curt Banks comes out of the room to call each one by his number.

Curt, the sergeant-at-arms, reads the prisoner’s parole statement, followed by the opposing statement of any of the guards to deny his parole. He escorts each to sit at the right-hand side of Carlo, who takes the lead from there. In order of appearance come Prisoner Jim-4325, Prisoner Glenn-3401, Prisoner Rich-1037, and finally Prisoner Hubbie-7258. After each has had his time before the Board, he is returned to the hallway bench, handcuffed, chained, and bagged until the session is completed and all the prisoners are returned to the prison basement.

Before the first prisoner appears, as I’m checking the video quality, the old-time pro, Carlo, begins to educate the Board neophytes on some basic Parole Board realities. (See Notes for his soliloquy.)

1 Curt Banks, sensing that Carlo is warming up to one of the long speeches he’s heard too often during our summer school course, says authoritatively, “We’ve gotta move, time is running.”

Prisoner 4325 Pleads Not Guilty

Prisoner Jim-4325 is escorted into the chamber; his handcuffs are removed, and he is offered a seat. He is a big, robust guy. Carlo challenges him right off with “Why are you in prison? How do you plead?” The prisoner responds, with all due seriousness, “Sir, I have been charged with assault with a deadly weapon. But I wish to plead not guilty to that charge.”

2

“Not guilty?” Carlo feigns total surprise. “So you’re implying that the officers who arrested you didn’t know what they were doing, that there’s been some mistake, some confusion? That the people who were trained in law enforcement, and presumably have had a number of years of experience, are prone to pick you up out of the entire population of Palo Alto and that they don’t know what they’re talking about, that they have some confusion in their minds about what you’ve done? In other words, they’re liars—are you saying that they’re liars?”

4325: “I’m not saying they’re liars, there must have been very good evidence and everything. I certainly respect their professional knowledge and everything. . . . I haven’t seen any evidence, but I assume it must be pretty good for them to pick me up.” (The prisoner is submitting to higher authority; his initial assertiveness is receding in the wake of Carlo’s dominating demeanor.)

Carlo Prescott: “In that case, you’ve just verified that there must be something to what they say.”

4325: “Well, obviously there must be something to what they say if they picked me up.”

Prescott starts with questions that explore the prisoner’s background and his future plans, but he is eager to know more about his crime: “What kinds of associations, what kinds of things do you do in your spare time that put you into a position to be arrested? That’s a serious charge . . . you know you can kill someone when you assault them. What did you do? You shoot them or stab them or—?”

4325: “I’m not sure, sir. Officer Williams said—”

Prescott: “What did you do? Shoot them or stab them or bomb them? Did you use one of those rifles?”

Craig Haney and other members of the Board try to ease the tension by asking the prisoner about how he has been adjusting to prison life.

4325: “Well, by nature I’m something of an introvert . . . and I guess the first few days I thought about it, and I figured that the very best thing to do was to behave . . .”

Prescott takes over again: “Answer his question, we don’t want a lot of intellectual bullshit. He asked you a direct question, now answer the question!”

Craig interrupts with a question about the rehabilitative aspects of the prison, to which the prisoner replies, “Well, yes, there’s some merit to it, I’ve certainly learned to be obedient, and at points of stress I’ve been somewhat bitter, but the correctional officers are doing their job.”

Prescott: “This Parole Board can’t hold your hand outside. You say they’ve taught you a degree of obedience, taught you how to be cooperative, but you won’t have anybody watching over you outside, you’ll be on your own. What kind of a citizen do you think you can make, with these kinds of charges against you? I’m looking over your charges here. This is quite a list!” With total assurance and dominance, Carlo looks over a totally blank notepad as if it were the prisoner’s “rap sheet,” filled with his convictions, and remarks about his pattern of arrests and releases. He continues, “You know, you tell us that you can make it out there as a result of the discipline you learned in here. We can’t hold your hand out there . . . what makes you think you can make it now?”

4325: “I’ve found something to look forward to. I am going to the University of California, to Berkeley, and going into a major. I want to try physics, I’m definitely looking forward to that experience.”

Prescott cuts him short and switches to interrogate him about his religious beliefs and then about why he has not taken advantage of the prison’s programs of group therapy or vocational therapy. The prisoner seems genuinely confused, saying he would have done so but he was never offered such opportunities. Carlo asks Curt Banks to check on the truth of that last assertion, which, he says, he personally doubts. (Of course, he knows that we have no such programs in this experiment, but it is what his parole board members have always asked him in the past.)

After a few more questions from other Board members, Prescott asks the correctional officer to take the inmate back to his cell. The prisoner stands and thanks the board. He then automatically extends his arms, palms facing each other, as the attending guard locks on the handcuffs. Jim-4325 is escorted out, re-bagged, and made to sit in silence in the hallway while the next prisoner has his turn at the Board.

After the prisoner leaves, Prescott notes for the record, “Well, that guy’s an awful smooth talker . . .”

My notes remind me that “Prisoner 4325 has appeared quite composed and generally in control of himself—he has been one of our ‘model prisoners’ so far. He seems confused by Prescott’s aggressive interrogation about the crime for which he was arrested, and is easily pushed into admitting that he’s probably guilty, despite the fact that his crime is completely fictional. Throughout the hearing, he is obedient and agreeable, which demeanor contributes to his relative success and probably longevity as a survivor in this prison setting.”

A Shining Example Is Dimmed

Next, Curt announces that Prisoner 3401 is ready for our board hearing, and reads aloud his appeal:

I want parole so that I may take my new life into this despairing world and show the lost souls that good behavior is rewarded with warm hearts; that the materialist pigs have no more than the impoverished poor; that the common criminal can be fully rehabilitated in less than a week, and that God, faith, and brotherhood are still strongly in us all. I deserve parole because I believe my conduct throughout my stay has been undoubtedly beyond reproach. I have enjoyed the comforts and find that it would be best to move on to higher and more sacred places. Also, being a cherished product of our environment, we all can be assured that my full rehabilitation is everlasting. God bless. Very truly yours, 3401. Remember me, please, as a shining example.

The guards’ counter-recommendations present a stark contrast:

3401 has been a constant two-bit troublemaker. Not only that, he is a follower, finding no good within himself to develop. He meekly mimics bad things. I recommend no parole. Signed by Guard Arnett.

I see no reason why 3401 deserves parole, nor can I even make the connection between the 3401 I know and the person described in this parole request. Signed by Guard Markus.

3401 doesn’t deserve parole and his own sarcastic request indicates this. Signed by Guard John Landry.

Prisoner 3401 is then brought in with the paper bag still over his head, which Carlo wants removed so he can see the face of this “little punk.” He and the other board members react with surprise when they discover that 3401, Glenn, is Asian American, the only non-Caucasian in the mix. Glenn is playing against type with his rebellious, flippant style. However, he fits the stereotype physically; a short five feet, two inches, slight but wiry build, cute face, and shiny jet black hair.

Craig starts by inquiring about the prisoner’s role in the prisoner uprising that started when his cell created the barricade. What did he do to stop it?

3401 replies with surprising bluntness: “I did not stop it, I encouraged it!” After further inquiry into this situation by other board members, 3401 continues in a sarcastic tone, so different from Prisoner 4325’s apparent humility, “I think the purpose of our institution is to rehabilitate the prisoners and not to antagonize them, and I felt that as a result of our actions—”

Warden Jaffe, seated along the side of the room and not at the Board table, cannot resist getting in his licks: “Perhaps you don’t have the proper notion of what rehabilitation is. We’re trying to teach you to be a productive member of society, not how to barricade yourself in the cell!”

Prescott has had enough of these diversions. He reasserts his role as head honcho: “At least two citizens have said that they observed you leaving the site of the crime.” (He has invented this on the spot.) Carlo continues, “To challenge the vision of three people is to say that all of humanity is blind!” Now, did you write that ‘God, faith, and brotherhood are still strong’? Is it brotherhood to take somebody else’s property?”

Carlo then moves in to play the obvious race card: “Very few of you Oriental people are in the prisons . . . in fact, they’re likely to be very good citizens. . . . You’ve been a constant troublemaker, you’ve mocked a prison situation here, you come in here and talk about rehabilitation as if you think you should be permitted to run a prison. You sit here at the table and you interrupt the warden by indicating that you think that what you’re saying is much more important than anything that he could say. Frankly, I wouldn’t parole you if you were the last man in the prison, I think you’re the least likely prospect of parole we have, what do you think about that?”

“You’re entitled to your opinion, sir,” says 3401.

“My opinion means something in this particular place!” Carlo retorts angrily.

Prescott asks more questions, not allowing the prisoner a chance to answer them, and ends up denouncing and dismissing 3401: “I don’t think we need to take any more time just now. I’m of the opinion that the record and his attitude in the boardroom indicate quite clearly what his attitude is . . . we’ve got a schedule, and I don’t see any reason to even discuss this. What we have here is a recalcitrant who writes nice speeches.”

Before leaving, the prisoner tells the Board that he has a skin rash that is going to break out and it is worrying him. Prescott asks whether he has seen a doctor, whether he has gone on sick call or done anything constructive to take care of his problem. When the prisoner says that he has not, Carlo reminds him that this is a parole board and not a medical board, and then dismisses his concern: “We try to find some reason to parole any man who comes in, and once you come into this particular prison it’s up to you to maintain a record, a kind of demeanor which indicates to us that you can make an adjustment to society. . . . I want you to consider some of the things that you wrote at an intrinsic level; you’re an intelligent man and know the language quite well, I think that you can probably change yourself, yes, you might have a chance to change yourself in the future.”

Carlo turns to the guard and gestures to take the prisoner away. A now-contrite little boy slowly raises his arms outstretched as handcuffs are applied, and out he goes. He may be realizing that his flippant attitude has cost him dearly, that he was not prepared for this event to be so serious and the Parole Board so intense.

My notes indicate that Prisoner 3401 is more complex than he appears initially. He reveals an interesting mix of traits. He is usually quite serious and polite when he is dealing with the guards in the prison, but in this instance, he has written a sarcastic, humorous letter requesting parole, referencing a nonexistent rehabilitation, mentioning his spirituality, and claiming to be a model prisoner. The guards don’t seem to like him, as is evident in their strong letters advising against parole. His bold parole request letter stands in striking contrast with his demeanor—the young man we see in this room, subdued, even cowed, by the experience. “No joking allowed here.” The Board, especially Prescott, goes after him viciously, yet he doesn’t cope with the attack effectively. As the hearing progresses, he becomes increasingly withdrawn and unresponsive. I wonder if he will survive the full two weeks.

A Rebel Relents

Next up is Prisoner 1037, Rich, whose mother was so worried about him last night when she visited and saw him looking so awful. He is the same one who blockaded himself in Cell 2 this morning. He is also a frequent occupant of the Hole. 1037’s appeal is interesting but loses something when read quickly in a flat, unemotional tone by Curt Banks:

I would like to be paroled so that I may spend the last moments of my teenage years with old friends. I will turn 20 on Monday. I believe that the correctional staff has convinced me of my many weaknesses. On Monday, I rebelled, thinking that I was being treated unjustly. However, that evening I finally realized that I was unworthy of better treatment. Since that time I have done my best to cooperate, and I now know that every member of the correctional staff is only interested in the well-being of myself and the other prisoners. Despite my horrible disrespect for them and their wishes, the prison staff has treated and is treating me well. I deeply respect their ability to turn the other cheek and I believe that because of their own goodness I have been rehabilitated and transformed into a better human being. Sincerely, 1037.

Three guards have provided a collective recommendation, which Curt reads aloud:

While 1037 is improving since his rebellion phase, I believe he has a bit more to develop before being exposed to the public as one of our corrected products. I agree with the other officers’ appraisal of 1037, and also with 1037, that he has gotten much better, but has not yet reached a perfectly acceptable level. 1037 has a way to go before parole, and is improving. I don’t recommend parole.

When Rich-1037 enters the room, he reveals a strange blend of youthful energy and incipient depression. Immediately, he talks about his birthday, his only reason to request parole; it happens to be very important to him, and he forgot about it when he originally signed up. He is in full swing when the warden asks him a question that he can’t answer without either getting into trouble or undoing his justification for leaving: “Don’t you think our prison is capable of giving you a birthday party?”

Prescott seizes the opportunity: “You’ve been in society for a while, even at your age. You know the rules. You must recognize that prisons are for people who break rules, and you place that in jeopardy by doing exactly what you did. Son, I recognize that you’re changing, it’s indicated here, and I think seriously that you’ve improved. But here, in your own handwriting, ‘despite my horrible disrespect for them and their wishes.’ Horrible disrespect! You can’t disrespect other people and their property. What would happen if everybody in this nation disrespected everybody else’s property? You’ll probably kill if you’re apprehended.”

As Carlo continues to seemingly review the prisoner’s record on his still blank notepad, he stops at the point where he has discovered something vital: “I see here in your arrest reports that you were quite cantankerous, in fact you had to be repressed, and you could have inflicted hurt or worse on some of the arresting officers. I’m very impressed by your progress, and I think that you’re beginning to recognize that your behavior has been immature and in many ways is entirely devoid of judgment and concern for other people. You turn people into sticks; you make them think that they are objects, for your use. You’ve manipulated people! All your life you seem to have manipulated people, all your reports talk about your indifference toward law and order. There are periods in which you don’t seem to control your behavior. What makes you think that you could be a good parole prospect? What could you tell us? We’re trying to help you.”

Prisoner 1037 is not prepared for this personal attack on his character. He mumbles an incoherent explanation for being able to “walk away” from a situation that might tempt him to behave violently. He goes on to say that this prison experience has helped him: “Well, I’ve gotten to see a lot of people’s different reactions to different situations, how they handled themselves with respect to other people, such as speaking with various cellmates, their reactions to the same situations. The three different shifts of guards, I’ve noticed the individual guards have small differences in the same situations.”

1037 then curiously brings up his “weaknesses,” namely his part as agitator in Monday’s prisoner rebellion. He has become entirely submissive, blaming himself for defying the guards and never once criticizing them for their abusive behavior and nonstop hassling. (Before my eyes is a perfect example of mind control in action. The process exactly resembles American POWs in the Korean War confessing publicly to using germ warfare and other wrongdoings to their Chinese Communist captors.)

Unexpectedly, Prescott interrupts this discussion of the prisoner’s weaknesses to ask assertively, “Do you use drugs?”

When 1037 replies “No,” he is allowed to continue apologizing until interrupted again. Prescott notices a black-and-blue bruise on the inmate’s arm and asks how he got that big bruise. Although it came from one or more of the scuffles between him and the guards, prisoner 1037 denies the guard’s part in restraining him or dragging him into solitary, saying that the guards had been as gentle as they could. By continually disobeying their orders, he says, he brought the bruise on himself.

Carlo likes that mea culpa. “Keep up the good work, huh?”

1037 says that he would consider parole even if it meant forfeiting his salary. (That seems rather extreme, given how much he has been through to have nothing to show for it.) Throughout he answers the Board’s questions competently, but his depression hovers over him, as Prescott notes in his comments after the hearing. His state of mind is something his mother detected immediately during her visit with him and in her complaints to me when she came to the Superintendent’s Office. It is as though he were trying to hang on as long as possible in order to prove his manliness—perhaps to his dad? He provides some interesting answers to questions about what he has gained from his experience in the prison, but most of them sound like superficial lines made up simply for the benefit of the Board.

The Good-Looking Kid Gets Trashed

Last in line is the handsome young prisoner Hubbie-7258, whose appeal Curt reads with a bit of scorn:

My first reason for parole is that my woman is going away on vacation very soon and I would like to see her a little bit more before she goes, seeing that when she gets back is just about the same time I leave for college. If I get back only after the full two weeks here, I will only see her for a total time of one-half hour. Here we can’t say good-bye and talk, with the correctional officer and the chaperone, the way we’d like to. Another reason is that I think that you have seen me and I know that I won’t change. By change I mean breaking any of the rules set down for us, the prisoners, thus putting me out on parole would save my time and your expenditures. It is true that I did attempt an escape with former cellmate 8612, but ever since then, as I sat in my empty cell with no clothes on I knew that I shouldn’t go against our correctional officers, so ever since then I have almost exactly followed all the rules. Also, you will note that I have the best cell in this prison.

Again, Guard Arnett’s recommendations are at odds with the prisoner’s statement: “7258 is a rebellious wise guy,” is Guard Arnett’s overall appraisal, which he follows up with this cynical condemnation: “He should stay here for the duration or until he rots, whichever comes later.”

Guard Markus is more sanguine: “I like 7258 and he is an all-right prisoner, but I don’t feel he is any more entitled to parole than any of the other prisoners, and I am confident that the prisoner experience will have a healthy effect on his rather unruly natural character.”

“I also like 7258, almost as much as 8612 [David, our spy], but I don’t think he should get parole. I won’t go as far as Arnett does, but parole shouldn’t be given,” writes John Landry.

As soon as the prisoner is unbagged, he beams his usual big toothy smile, which irritates Carlo enough to spur his jumping all over him.

“As a matter of fact, this whole thing’s funny to you. You’re a ‘rebellious wise guy,’ as the guard’s report accurately describes you. Are you the kind of person who doesn’t care anything about your life?”

As soon as he starts to answer, Prescott changes course to ask about his education. “I plan to start college in the fall at Oregon State U.” Prescott turns to other Board members. “Here’s what I say. You know what, education is a waste on some people. Some people shouldn’t be compelled to go to college. They’d probably be happier as a mechanic or a drugstore salesman,” waving his hand disdainfully at the prisoner. “Okay, let’s move on. What did you do to get in here?”

“Nothing, sir, but to sign up for an experiment.”

This reality check might otherwise threaten to unravel the proceedings, but not with skipper Prescott at the helm:

“So wise guy, you think this is just an experiment?” He takes back the steering wheel, pretending to examine the prisoner’s dossier. Prescott notes matter-of-factly, “You were involved in a burglary.”

Prescott turns to ask Curt Banks whether it was first- or second-degree burglary; Curt nods “first.”

“First, huh, just as I thought.” It is time to teach this Young Turk some of life’s lessons, starting with reminding him of what happens to prisoners who are caught in an escape attempt. You’re eighteen years old, and look what you’ve done with your life! You sit here in front of us and tell us that you’d even be willing to forfeit compensation to get out of prison. Everywhere I look in this report I see the same thing: ‘wise guy,’ ‘smart aleck,’ ‘opposed to any sort of authority’! Where did you go wrong?”

After asking what his parents do, his religious background, and whether he goes to church regularly, Prescott is angered by the prisoner’s statement that his religion is “nondenominational.” He retorts, “You haven’t even decided about something as important as that either.”

The angered Prescott gets up and storms out of the room for a few minutes, as the other Board members ask some standard questions about how he plans to behave in the next week if his parole request is not granted.

Forfeiting Pay for Freedom

This break in the highly tense action gives me time to realize the importance of Prisoner 1037’s assertion of willing to forfeit his pay for parole. We need to formalize that as a critical final question to be put to each of the prisoners. I tell Carlo to ask them, “Would you be willing to forfeit all the money you have earned as a prisoner if we were to parole you?”

At first, Carlo poses a more extreme form of the question: “How much would you be willing to pay us to get out of here?” Confused, Prisoner 7258 says he won’t pay money to be released. Carlo reframes the question, asking whether the prisoner would forfeit the money he’s made so far.

“Yes, indeed, sir, I would do that.”

Prisoner 7258 doesn’t come across as particularly bright or self-aware. He also doesn’t seem to take his entire situation as seriously as some of the other prisoners do. He is the youngest, barely eighteen, and is quite immature in his attitudes and responses. Nevertheless, his detachment and sense of humor will serve him well in coping with most of what is in store for him and his peers in the week ahead.

Next, we have each of the prisoners return to the parole chamber to answer that same final question about forfeiting their pay in exchange for parole. Prisoner 1037, the rebellious birthday boy, says yes to forfeiting his money if paroled. The cooperative Prisoner 4325 answers in the affirmative as well. Only Prisoner 3401, the defiant Asian American, would not want parole if it involved forfeiting his money, since he really needs it.

In other words, three of these four young men want to be released so badly that they are willing to give up the hard-earned salary they have earned in their twenty-four-hour-a-day job as prisoners. What is remarkable to me is the power of the rhetorical frame in which this question is put. Recall that the primary motivation of virtually all the volunteers was financial, the chance to make fifteen dollars a day for up to two weeks at a time when they had no other source of income, just before school was to start in the fall. Now, despite all their suffering as prisoners, despite the physical and psychological abuse they have endured—the endless counts; the middle-of-the-night awakenings; the arbitrary, creative evil of some of the guards; the lack of privacy; the time spent in solitary; the nakedness; the chains; their bagged heads; the lousy food and minimal bedding—the majority of the prisoners are willing to leave without pay to get out of this place.

Perhaps even more remarkable is the fact that after saying that money was less important than their freedom, each prisoner passively submitted to the system, holding out his hands to be handcuffed, submitting to the bag being put back over his head, accepting the chain on his leg, and, like sheep, following the guard back down to that dreadful prison basement. During their Parole Board hearing, they were physically out of the prison, in the presence of some “civilians” who were not directly associated with their tormentors downstairs. Why did none of them say, “Since I do not want your money, I am free to quit this experiment and demand to be released now.” We would have had to obey their request and terminate them at that moment.

Yet none did. Not one prisoner later told us that he had even considered that he could quit the experiment because virtually all of them had stopped thinking of their experience as just an experiment. They felt trapped in a prison being run by psychologists, not by the State, as 416 had told us. What they had agreed to do was forfeit money they had earned as prisoners—if we chose to parole them. The power to free or bind was with the Parole Board, not in their personal decision to stop being a prisoner. If they were prisoners, only the Parole Board had the power to release them, but if they were, as indeed they were, experimental subjects, each of the students always held the power to stay or quit at any time. It was apparent that a mental switch had been thrown in their minds, from “now I am a paid experimental volunteer with full civil rights” to “now I am a helpless prisoner at the mercy of an unjust authoritarian system.”

During the postmortem, the Board discussed the individual cases and the overall reactions of this first set of prisoners. There was a clear consensus that all the prisoners seemed nervous, edgy, and totally consumed by their role as prisoners.

Prescott sensitively shares his real concerns for Prisoner 1037. He accurately detects a deep depression building in this once fearless rebel ringleader: “It’s just a feeling that you get, living around people who jump over prison tiers to their deaths, or cut their wrists. Here’s a guy who had himself together sufficiently to present himself to us, but there were lags between his answers. Then the last guy in, he’s coherent, he knows what’s happened, he still talks about ‘an experiment,’ but at the same time, he’s willing to sit and talk about his father, he’s willing to sit and talk about his feelings. He seemed unreal to me, and I’m basing that just on the feeling I had. The second guy, the Oriental [Asian-American] prisoner, he’s a stone. To me, he was like a stone.”

In summation, Prescott offers the following advice: “I join the rest of the group and propose letting a couple of prisoners out at different times, to try to get the prisoners trying to figure out what they have to begin to do in order to get out. Also, releasing a few prisoners soon would give some hope to the rest of them, and relieve some of their feelings of desperation.”

The consensus seems to be to release the first prisoner soon, big Jim-4325, and then number three, Rich-1037, later on, perhaps replacing them with other standby prisoners. There are mixed feelings about whether 3401 or 7258 should be released next, or at all.

What Have We Witnessed Here?

Three general themes emerge from the first Parole Board hearings: the boundaries between simulation and reality have been blurred; the prisoners’ subservience and seriousness has steadily increased in response to the guards’ ever-greater domination, and there has been a dramatic character transformation in the performance of the Parole Board head, Carlo Prescott.

Blurring the Line Between the Prison Experiment and the Reality of Imprisonment

Impartial observers not knowing what had preceded this event might readily assume that they were witnessing an actual hearing of a local prison parole board in action. The strength and manifest reality of the dialectic at work between those imprisoned and society’s appointed guardians of them was reflected in many ways, among them, the overall seriousness of the situation, the formality of the parole requests by inmates, the opposing challenges from their guards, the diverse composition of all the Parole Board members, the nature of the personal questions put to the inmates, and accusations made against them—in short, the intense affective quality of the entire proceeding. The basis of this interaction is obvious in the Board’s questions and prisoners’ answers regarding “past convictions,” the rehabilitative activities of attending classes or participating in therapy or vocational training sessions, arranging for legal representation, the status of their trial, and their future plans for becoming good citizens.

It is as hard to realize that barely four days have passed in the lives of these student experimental volunteers as it is to imagine that their future as prisoners is little more than another week in the Stanford County Jail. Their captivity is not the many months or long years that the mock Parole Board seems to imply in its judgments. Role playing has become role internalization; the actors have assumed the characters and identities of their fictional roles.

The Prisoners’ Subservience and Seriousness

By this point, for the most part, the prisoners have slipped reluctantly, but finally compliantly, into their highly structured roles in our prison. They refer to themselves by their identification numbers and answer immediately to questions put to their anonymous identities. They answer what should be ridiculous questions with full seriousness, for example inquiries into the nature of their crimes and their rehabilitation efforts. With few exceptions, they have become completely subservient to the authority of the Parole Board as well as to the domination of the correctional officers and the system in general. Only Prisoner 7258 had the temerity to refer to his reason for being here as volunteering for an “experiment,” but he quickly backed away from that assertion under Prescott’s verbal assaults.

The flippant style of some of their original parole requests, notably that of Prisoner 3401, the Asian-American student, withers under the negative judgment of the Board that such unacceptable behavior does not warrant release. Most of the prisoners seem to have completely accepted the premises of the situation. They no longer object to or rebel against anything they are told or commanded to do. They are like Method actors who continue to play their roles when offstage and off camera, and their role has come to consume their identity. It must be distressing to those who argue for innate human dignity to note the servility of the former prisoner rebels, the heroes of the uprisings, who have been reduced to beggars. No heroes are stepping out from this aggregation.

That feisty Asian-American prisoner, Glenn-3401, had to be released some hours after his stressful Parole Board experience, when he developed a full-body rash. Student Health Services provided the appropriate medication, and he was sent home to consult his own physician. The rash was his body’s way of getting his release, as was Doug-8612’s raging loss of emotional control.

The Dramatic Transformation of the Parole Board Head

I had known Carlo Prescott for more than three months before this event and had interacted with him almost daily in person and in frequent and long phone calls. As we co-taught a six-week-long course on the psychology of imprisonment, I had seen him in action as an eloquent, vehement critic of the prison system, which he judged to be a fascist tool designed to oppress people of color. He was remarkably perceptive in the ways in which prisons and all other authoritarian systems of control can change all those in their grip, both the imprisoned and their imprisoners. Indeed, during his Saturday-evening talk-show program on the local radio station KGO, Carlo frequently made his listeners aware of the failure of this antiquated, expensive institution that their tax dollars were wasted in continuing to support.

He had told me of the nightmares he would have anticipating the annual Parole Board hearings, in which an inmate has only a few minutes to present his appeal to several Board members, who do not seem to be paying any attention to him as they thumb through fat files while he pleads his case. Perhaps some of the files are not even his but are those of the next prisoner in line, and reading them now will save time. If you are asked questions about your conviction or anything negative in your rap sheet, you know immediately that parole will be delayed for at least another year because defending the past prevents you from envisioning anything positive in your future. Carlo’s tales enlightened me about the kind of rage that such arbitrary indifference generates in the vast majority of prisoners who are denied parole year after year, as he was.

3

However, what are the deeper lessons to be learned from such situations? Admire power, detest weakness. Dominate, don’t negotiate. Hit first when they turn the other cheek. The golden rule is for them, not for us. Authority rules, rules are authority.

These are also some of the lessons learned by boys of abusive fathers, half of whom are transformed into abusive fathers themselves, abusing their children, spouses, and parents. Perhaps half of them identify with the aggressor and perpetuate his violence, while the others learn to identify with the abused and reject aggression for compassion. However, research does not help us to predict which abused kids will later become abusers and which will turn out to be compassionate adults.

Time Out for a Demonstration of Power Without Compassion

I am reminded of the classic demonstration by an elementary school teacher, Jane Elliott, who taught her students the nature of prejudice and discrimination by arbitrarily relating the eye color of children in her classroom to high or low status. When those with blue eyes were associated with privilege, they readily assumed a dominant role over their brown-eyed peers, even abusing them verbally and physically. Moreover, their newly acquired status spilled over to enhance their cognitive functioning. When they were on top, the blue-eyes improved their daily math and spelling performances (statistically significant, as I documented with Elliott’s original class data). Just as dramatically, test performance of the “inferior” brown-eyed children deteriorated.

However, the most brilliant aspect of her classroom demonstration with these third-grade schoolchildren from Riceville, Iowa, was the status reversal the teacher generated the next day. Mrs. Elliott told the class she had erred. In fact, the opposite was true, she said; brown eyes were better than blue eyes! Here was the chance for the brown-eyed children, who had experienced the negative impact of being discriminated against, to show compassion now that they were on top of the heap. The new test scores reversed the superior performance of the haves and diminished the performance of the have-nots. But what about the lesson of compassion? Did the newly elevated brown-eyes understand the pain of the underdog, of those less fortunate, of those in a position of inferiority that they had personally experienced one brief day earlier?

There was no carryover at all! The brown-eyes gave what they got. They dominated, they discriminated, and they abused their former blue-eyed abusers.

4 Similarly, history is filled with accounts showing that many of those escaping religious persecution show intolerance of people of other religions once they are safe and secure in their new power domain.

Back to Brown-Eyed Carlo

This is a long side trip around the issue surrounding my colleague’s dramatic transformation when he was put into the powerful position as head of the Parole Board. At first, he gave a truly outstanding improvisational performance, like a Charlie Parker solo. He improvised details of crimes, of the prisoners’ past histories, on the spot, out of the blue. He did so without hesitation, with a fluid certainty. However, as time wore on, he seemed to embrace his new authority role with ever-increasing intensity and conviction. He was the head of the Stanford County Jail Parole Board, the authority whom inmates suddenly feared, to whom his peers deferred. Forgotten were the years of suffering he had endured as a brown-eyed inmate once he was granted the privileged position of seeing the world through the eyes of the all-powerful head of this Board. Carlo’s statement to his colleagues at the end of this meeting showed the agony and disgust his transformation had instilled in him. He had become the oppressor. Later that night, over dinner, he confided that he had been sickened by what he had heard himself say and had felt when he was cloaked in his new role.

I wondered if his reflections would cause him to show the positive effects of his acquired self-knowledge when he headed the next Parole Board meeting on Thursday. Would he show greater consideration and compassion for the new set of prisoners who would be pleading to him for parole? Or would the role remake the man?

THURSDAY’S MEETING OF THE PAROLE AND DISCIPLINARY BOARD

The next day brings four more prisoners before a reconstituted Parole Board. Except for Carlo, all the other members of the Board are newcomers. Craig Haney, who had to leave town for urgent family business in Philadelphia, is replaced by another social psychologist, Christina Maslach, who quietly observes the proceedings with little apparent direct involvement—at this time. A secretary and two graduate students fill out the rest of this five-person Board. However, at the urging of the guards, in addition to considering parole requests, the Board also considers various disciplinary actions against the more serious troublemakers. Curt Banks continues in his role as sergeant-at-arms, and Warden David Jaffe also sits in to observe and comment when appropriate. Again I watch from behind the one-way viewing screen and record the proceedings for subsequent analysis on our Ampex video recorder. Another variation from yesterday is that we do not have the prisoners sit around the same table with the Board but separately in high chairs, on a pedestal, so to speak—all the better to observe them as in police detective interrogations.

A Hunger Striker Strikes Out

First up on the docket is Prisoner 416, recently admitted, who is still on a hunger strike. Curt Banks reads off the disciplinary charges that several guards have filed against him. Guard Arnett is especially angered at 416; he and the other guards are not sure what to make of him: “Here for such a short time, and he has been totally recalcitrant, disrupting all order and our routine.”

The prisoner immediately agrees that they are right; he will not dispute any of the charges. He insists on securing legal representation before he consents to eat anything served him in this prison. Prescott goes after his demand for “legal aid,” forcing a clarification.

Prisoner 416 replies in a strange fashion: “I’m in prison, for all practical purposes, because I signed a contract, which I’m not of legal age to sign.” In other words, either we must get a lawyer to take his case and get him released, or he will continue with his hunger strike and get sick. Thus, he reasons, the prison authorities will be forced to release him.

This scrawny youngster presents much the same face to the Board that he does to the guards: he is intelligent, self-determined, and strong willed in his opinions. However, his justification for disputing his imprisonment—that he was not of legal age to sign the research informed consent contract—seems strangely legalistic and circumstantial for a person who has typically acted from ideological principles. Despite his disheveled, gaunt appearance, there is something about 416’s demeanor that does not elicit sympathy from anyone who interacts with him—neither the guards, the other prisoners, nor this board. He looks like a homeless street person who makes passersby feel more guilty than sympathetic.

When Prescott asks on what charge 416 is in jail for, the prisoner responds, “There is no charge, I have not been charged. I was not arrested by the Palo Alto police.”

Incensed, Prescott asks if 416 is in jail by mistake, then. “I was a standby, I—” Prescott is fuming now and confused. I realize that I had not briefed him on how 416 differed from all the others, as a newly admitted standby prisoner.

“What are you, anyway, a philosophy major?” Carlo takes time to light his cigarette and perhaps plan a new line of attack. “You been philosophizing since you’ve been in here.”

When one of the secretaries on today’s Board recommends exercise as a form of disciplinary action and 416 complains that he has been forced to undergo too much exercise, Prescott curtly replies, “He looks like a strong fellow, I think exercise would be ideal for him.” He looks over at Curt and Jaffe to put that on their action list.

Finally, when asked the loaded question—Would he be willing to forfeit all the money he has earned as a prisoner if a parole were granted?—416 immediately and defiantly replies, “Yes, of course. Because I don’t feel that the money is worth the time.”

Carlo has had enough of him. “Take him away.” 416 then does exactly what the others before him have done like automatons; without instruction he stands up, arms outstretched to be handcuffed, head bagged, and escorted away from these proceedings.

Curiously, he does not demand that the Board act now to terminate his role as a reluctant student research volunteer. He doesn’t want any money, so why does he not simply say, “I quit this experiment. You must give me my clothes and belongings, and I am out of here!”

This prisoner’s first name is Clay, but he will not be molded easily by anyone; he stands firmly by his principles and obstinately in the strategy he has advanced. Nevertheless, he has become too embedded in his prisoner identity to do the macroanalysis that should tell him he has now been given the keys to freedom by insisting to the Parole Board that he must be allowed to quit here and now while he is physically removed from the prison venue. However, he is now carrying that venue within his head.

Addicts Are Easy Game

Prisoner Paul-5704, next at bat, immediately complains about how he’s missing the cigarette ration that he was promised for good behavior. His disciplinary charges by the guards include “Constantly and grossly insubordinate, with flares of violence and dark mood, and constantly tries to incite the other prisoners to insubordination and general uncooperativeness.”

Prescott challenges his so-called good behavior, which will never get him another cigarette again. The prisoner answers in such a barely audible voice that Board members have to ask him to speak louder. When he is told that he acts badly even when he knows it will mean punishment for other prisoners, he again mumbles, staring toward the center of the table.

“We’ve discussed that . . . well, if something happens, we’re just going to follow through with it . . . if someone else was doing something, I’d go through punishment for them.” A Board member interrupts, “Have you gone through punishment for any of the other prisoners?” Paul-5704 responds yes, he has suffered for his comrades.

Prescott loudly and mockingly declares, “You’re a martyr, then, huh?”

“Well, I guess we all are . . . ,” 5704 says, again barely audible.

“What have you got to say for yourself?” Prescott demands. 5704 responds, but again it is unintelligible.

Recall that 5704, the tallest prisoner, had challenged many of the guards openly and been the insider in various escape attempts, rumors, and barricades. He was also the one who had written to his girlfriend expressing his pride at being elected head of the Stanford County Jail Prisoners’ Grievance Committee. Further, it was this same 5704 who had volunteered for this experiment under false pretenses. He signed up with the intention of being a spy who was going to expose this research in articles he planned to write for several alternative, liberal, “underground” newspapers, on the assumption that this experiment was no more than a government-supported project for learning how to deal with political dissidents. Where had all that former bravado gone? Why had he suddenly become incoherent?

Before us in this room sits a subdued, depressed young man. Prisoner 5704 simply stares downward, nodding answers to the questions posed by the Parole Board, never making direct eye contact.

“Yes, I would be willing to give up any pay I’ve earned to get paroled now, sir,” he answers as loudly as he can muster strength to do. (The tally is now yes from five of the six prisoners.)

I wonder how that dynamic, passionate, revolutionary spirit, so admirable in this young man, could have vanished so totally in such a short time?

As an aside, we later learned that it was Paul-5704 who had gotten so deeply into his prisoner role that as the first part of his escape plan he had used his long, hard, guitar-player fingernails to unscrew one of the electrical power plates from the wall. He then used that plate to help remove the doorknob on his cell. He also used those tough nails to mark on the wall of his cell the passage of days of his confinement with notches next to M/ T /W/ Th/, so far.

A Puzzling, Powerful Prisoner

The next parole request comes from Prisoner Jerry-5486. He is even more puzzling than those who appeared earlier. He shows an upbeat style, a sense of being able to cope quietly with whatever is coming his way. His physical robustness is in stark contrast to that of Prisoner 416 or some of the other slim prisoners, like Glenn-3401. Surely there is the sense that he will endure the full two weeks without complaint. However, there is insincerity in his statements, and he has shown little overt support for any of his comrades in distress. In a few minutes here, 5486 manages to antagonize Prescott as much as any other prisoner has. He answers immediately that he would not be willing to give up the pay he’s earned so far in exchange for parole.

The guards report that 5486 does not deserve parole consideration because “he made a joke out of letter writing, and for his general non-cooperation.” When asked to explain his action, Prisoner 5486 responds that “I knew it wasn’t a legitimate letter . . . it didn’t seem to be . . .”

Guard Arnett, who has been standing aside silently observing the proceedings, can’t help but interrupt: “Did the correctional officers ask you to write the letter?” 5486 responds affirmatively, as Guard Arnett continues, “And you’re saying that the correctional officers asked you to write a letter that was not legitimate?”

5486 backtracks: “Well, maybe I chose the wrong word . . .”

But Arnett does not let up. He reads his report to the Board: “5486 has been on a gradual downhill slide . . . he has become something of a jokester and minor cutup.”

“You find that funny?” Carlo challenges him.

“Everybody [in the room] was smiling. I wasn’t smiling till they smiled,” 5486 replies defensively.

Carlo ominously interjects, “Everyone else can afford a smile—we’re going home tonight.” Still, he attempts to be less confrontational than the day before, and he asks a series of provocative questions: “If you were in my place, with the evidence I have, along with the report from staff, what would you do? How would you act? What would you do? What do you think is right for yourself?”

The prisoner answers evasively but never fully addresses those difficult questions. After a few more questions from the other members of the Board, an exasperated Prescott dismisses him: “I think we’ve seen enough, I think we know what we need to do. I don’t see any reason to waste our time.”

The prisoner is surprised at being dismissed so abruptly. It is apparent to him that he has created a bad impression on those he should have persuaded to support his cause—if not for this parole, then for the next time the Board meets. He has not acted in his best interests at this time. Curt has the guard handcuff him, place the bag over his head, and sit him on the bench in the hallway, awaiting the disposition of the next and final case before the prisoners are hauled back downstairs to resume their prison life.

Sarge’s Surface Tension

The final inmate for the Board to evaluate is “Sarge,” Prisoner 2093, who, true to type, sits upright in the high chair, chest out, head back, chin tucked in—a perfect military posture if I have ever seen one. He requests parole so that he can put his time “to more productive use,” and he notes further that he has “followed all rules from Day One.” Unlike most of his peers, 2093 would not give up the pay in exchange for parole.

“Were I to give up the pay I have earned thus far, it would be an even greater loss of five days of my life than it would have been otherwise.” He adds that the relatively small pay hardly compensates for the time he has served.

Prescott goes after him for not sounding “genuine,” for having thought everything out in advance, for not being spontaneous, for using words to disguise his feelings. Sarge apologizes for giving that impression because he always means what he says and tries hard to articulate clearly what he means. That softens Carlo, who assures Sarge that he and the Board will consider his case very seriously and then commends him for his good work in the prison.

Before ending the interview, Carlo asks Sarge why he didn’t request parole the first time it was offered to all prisoners. Sarge explains, “I would have requested parole the first time only if not enough other prisoners requested it.” He felt that other prisoners were having a harder time in the prison than he was, and he didn’t want his request to be placed above another’s. Carlo gently rebukes him for this show of shining nobility, which he thinks is a crass attempt to influence the Board’s judgment. Sarge’s show of surprise makes it evident that he meant what he said and was not attempting to impress the Board or anyone else.

This apparently intrigues Carlo, and he aims to learn about the young man’s private life. Carlo asks about Sarge’s family, his girlfriend, what kind of movies he likes, whether he takes time to buy an ice cream cone—all the little things that, taken together, give someone a unique identity.

Sarge replies matter-of-factly that he doesn’t have a girlfriend, seldom goes to movies, and that he likes ice cream but has not been able to afford to buy a cone recently. “All I can say is that after having gone to summer quarter at Stanford and living in the back of my car, I had a little difficulty sleeping the first night because the bed was too soft here in prison, and also that I have been eating better in prison than I had for the past two months, and that I had more time to relax than I had the last two months. Thank you, sir.”

Wow! What a violation of expectation this young man offers us. His sense of personal pride and stocky build belie his having gone hungry all summer and not having had a bed to sleep in while he attended summer school. That the horrid living conditions in our prison could be a better lifestyle for any college student comes as a shocker to us all.

In one sense, Sarge seems to be the most one-dimensional, mindlessly obedient prisoner of all, yet he is the most logical, thoughtful, and morally consistent prisoner of the group. It occurs to me that one problem this young man might have stems from his commitment to living by abstract principles and not knowing how to live effectively with other people or how to ask others for the support he needs, financial, personal, and emotional. He seems so tightly strung by this inner resolve and his outer military posturing that no one can really get access to his feelings. He may end up having a harder life than the rest of his fellows.

Contrition Doesn’t Cut the Mustard

Just as the Board is preparing to end this session, Curt announces that Prisoner 5486, the flippant one, wants to make an additional statement to the Board. Carlo nods okay.

5486 contritely says that he didn’t express what he really wanted to say, because he hadn’t had a chance to think about it fully. He’s experienced a personal decline while in this prison, because at first he expected to go to a trial and now he’s given up on his hope for justice.

Guard Arnett, sitting behind him, relates a conversation they had during lunch today. in which 5486 said that his decline must have been because “he’s fallen in with bad company.”

Carlo Prescott and the Board are obviously confused by this transaction. How does this statement promote his cause?

Prescott is clearly upset at this display. He tells 5486 that if the Board were going to make any recommendations, “I would see to it personally that you were here until the last day. Nothing against you personally, but we’re here to protect society. And I don’t think that you can go out and do a constructive job, do the kinds of things that will make you an addition to the community. You went outside that door and you realized that you had talked to us like we were a couple of idiots, and you were dealing with cops or authority figures. You don’t get along well with authority figures, do you? How do you get along with your folks? But what I’m trying to say is that you went outside the door and had a little time to think; now you’re back in here trying to con us into looking at you with a different view. What real social consciousness do you have? What do you think you really owe society? I want to hear something real from you.” (Carlo is back in Day 1 form!)

The prisoner is taken aback by this frontal assault on his character, and he scurries to make amends: “I have a new teaching job. It’s a worthwhile job, I feel.”

Prescott is not buying his story: “That may even make you more suspect. I don’t think I’d want you to teach any of my youngsters. Not with your attitude, your gross immaturity, your indifference to responsibility. You can’t even handle four days of prison without making yourself a nuisance. Then you tell me that you want to do a teaching job, do something that’s really a privilege. It’s a privilege to come into contact with decent people and have something to say to them. I don’t know, you haven’t convinced me. I just read your record for the first time, and you haven’t showed me anything. Officer, take him away.”

Chained, bagged, and carted back down to the basement prison, the prisoner will have to put on a better show at the next parole hearing—assuming he is granted the privilege again.

When a Paroled Prisoner Becomes the Chairman of the Parole Board

Before we return to what has been happening down below on the Yard in our absence during these two Parole Board time-aways, it is instructive to note the effect that this role-playing has had on our tough chairman of this “Adult Authority Hearing.” A month later, Carlo Prescott offered a tender personal declaration of the impact this experience had on him:

“Whenever I came into the experiment, I invariably left with a feeling of depression—that’s exactly how authentic it was. The experiment stopped being an experiment when people began to react to various kinds of things that happened during the course of the experiment. I noted in prison, for example, that people who considered themselves guards had to conduct themselves in a certain way. They had to put across certain impressions, certain attitudes. Prisoners in other ways had their certain attitudes, certain impressions that they acted out—the same thing occurred here.

“I can’t begin to believe that an experiment permitted me, playing a board member, the chairman of the board—the Adult Authority Board—to say to one of the prisoners, ‘How is it’—in the face of his arrogance and his defiant attitude— ‘how is it that Orientals seldom come to prison, seldom find themselves in this kind of a situation? What did you do?’

“It was at that particular point in the study that his whole orientation changed. He begin to react to me as an individual, he began to talk to me about his personal feelings. One man was so completely involved that he came back into the room as if he thought a second journey into the room to speak to the Adult Authority Board could result in his being paroled sooner.”

Carlo continues with this self-disclosure: “Well, as a former prisoner, I must admit that each time I came here, the frictions, suspicion, the antagonism expressed as the men got into the roles . . . made me recognize the kind of deflated impression which came about as a result of the confinement. That’s exactly what it was that induced in me a deep feeling of depression, as if I were back in a prison atmosphere. The whole thing was authentic, not make-believe at all.

“[The prisoners] were reacting as human beings to a situation, however improvisational, that had become part of what they were experiencing at that particular time. I imagine that as such, it reflected the kind of metamorphosis that takes place in a prisoner’s thinking. After all, he is completely aware of the things that are going on in the external world—the bridge building, the birth of children—they have absolutely nothing to do with him. For the first time he is totally alienated from the rest of society—from humanity, for that matter.

“His fellows, in their funk and stink and their bitterness, become his comrades, and all other things except for an occasional period when he can, as a result of a visit, as a result of something happening, like going to the Parole Board, there’s no reason to ever identify with where you came from. There is just that time, that instant.

“. . . I wasn’t surprised, nor was it a great pleasure to find my belief confirmed that ‘people become the role they enact’; that guards become symbols of authority and cannot be challenged; and that there are no rules or no rights they are obliged to grant prisoners. This happens with prison guards, and this happens with college students playing at prison guards. The prisoner, on the other hand, who is left to consider his own situation in regard to how defiant he is, how effective he is in keeping the experience away from him, comes face-to-face daily with his own helplessness. He has to correlate both his own hatred and the effectiveness of his defiance with the reality that regardless of how heroic or how courageous he sees himself at a certain time—he will still be counted and still be subjected to the rules and regulations of the prison.”

5

I think it is appropriate to end these deliberations with a similarly insightful passage from the letters of the political prisoner George Jackson, written a bit before Carlo’s statement. Recall that his lawyer wanted me to be an expert witness in his defense in the upcoming Soledad Brothers trial; however, Jackson was killed before I could do so, one day after our study ended.

It is strange indeed that a man can find anything to laugh at in here. Everyone is locked up twenty-four hours a day. They have no past, no future, no goal other than the next meal. They’re afraid, confused and confounded by a world they know that they did not make, that they feel they cannot change, so they make those loud noises so they won’t hear what their mind is trying to tell them. They laugh to assure themselves and those around them that they are not afraid, sort of like the superstitious individual who will whistle or sing a happy number as he passes the graveyard.

6