CHAPTER TEN

The SPE’s Meaning and Messages: The Alchemy of Character Transformations

We’re all guinea pigs in the laboratory of God . . . Humanity is just a work in progress.

—Tennessee Williams, Camino Real (1953)

THE STANFORD PRISON Experiment began as a simple demonstration of the effects that a composite of situational variables has on the behavior of individuals role-playing prisoners and guards in a simulated prison environment. For this exploratory investigation, we were not testing specific hypotheses but rather assessing the extent to which the external features of an institutional setting could override the internal dispositions of the actors in that environment. Good dispositions were pitted against a bad situation.

However, over time, this experiment has emerged as a powerful illustration of the potentially toxic impact of bad systems and bad situations in making good people behave in pathological ways that are alien to their nature. The narrative chronology of this study, which I have tried to re-create faithfully here, vividly reveals the extent to which ordinary, normal, healthy young men succumbed to, or were seduced by, the social forces inherent in that behavioral context—as were I and many of the other adults and professionals who came within its encompassing boundaries. The line between Good and Evil, once thought to be impermeable, proved instead to be quite permeable.

It is time now for us to review other evidence that we collected during the course of our research. Many quantitative sources of information shed additional light on what happened in that dark basement prison. Therefore, we must use all the available evidence to extract the meanings that have emerged from this unique experiment and to establish the ways in which humanity can be transformed by power and by powerlessness. Underlying those meanings are significant messages about the nature of human nature and the conditions that can diminish or enrich it.

SUMMING UP BEFORE DIGGING INTO THE DATA

As you have seen, our psychologically compelling prison environment elicited intense, realistic, and often pathological reactions from many of the participants. We were surprised both by the intensity of the guards’ domination and the speed with which it appeared in the wake of the prisoner rebellion. As in the case of Doug-8612, we were surprised that situational pressures could overcome most of these normal, healthy young men so quickly and so extremely.

Experiencing a loss of personal identity and subjected to arbitrary continual control of their behavior, as well as being deprived of privacy and sleep, generated in them a syndrome of passivity, dependency, and depression that resembled what has been termed “learned helplessness.”

1 (Learned helplessness is the experience of passive resignation and depression following recurring failure or punishment, especially when it seems arbitrary and not contingent upon one’s actions.)

Half of our student prisoners had to be released early because of severe emotional and cognitive disorders, transient but intense at the time. Most of those who remained for the duration generally became mindlessly obedient to the guards’ demands and seemed “zombie-like” in their listless movements while yielding to the whims of the ever-escalating guard power.

As with the rare “good guards,” so too, a few prisoners were able to stand up to the guards’ domination. As we have seen, Clay-416, who should have been supported for his heroic passive resistance, instead was harassed by his fellow prisoners for being a “troublemaker.” They adopted the narrow dispositional perspective provided by the guards rather than generate their own metaperspective on Clay’s hunger strike as emblematic of a path for their communal resistance against blind obedience to authority.

Sarge also behaved heroically at times by refusing to curse or verbally abuse a fellow prisoner when ordered to do so, but at all other times he was the model obedient prisoner. Jerry-486 emerged as our most evenly balanced prisoner; however, as he indicates in his personal reflections, he survived only by turning inward and not doing as much as he might to help the other prisoners, who could have benefited from his support.

When we began our experiment, we had a sample of individuals who did not deviate from the normal range of the general educated population on any of the dimensions we had premeasured. Those randomly assigned to the role of “prisoner” were interchangeable with those in the “guard” role. Neither group had any history of crime, emotional or physical disability, or even intellectual or social disadvantage that might typically differentiate prisoners from guards and prisoners from the rest of society.

It is by virtue of this random assignment and the comparative premeasures that I am able to assert that these young men did not import into our jail any of the pathology that subsequently emerged among them as they played either prisoners or guards. At the start of this experiment, there were no differences between the two groups; less than a week later, there were no similarities between them. It is reasonable, therefore, to conclude that the pathologies were elicited by the set of situational forces constantly impinging upon them in this prisonlike setting. Further, this Situation was sanctioned and maintained by a background System that I helped to create. I did so first when I gave the new guards their psychological orientation and then with the development of various policies and procedures that I and my staff helped to put into operation.

Neither the guards nor the prisoners could be considered “bad apples” prior to the time when they were so powerfully impacted by being embedded in a “bad barrel.” The complex of features within that barrel constitute the situational forces in operation in this behavioral context—the roles, rules, norms, anonymity of person and place, dehumanizing processes, conformity pressures, group identity, and more.

WHAT DID WE LEARN FROM OUR DATA?

The around-the-clock direct observations that we made of behavioral interactions between prisoners and guards, and of special events, were supplemented by videotaped recordings (about twelve hours), concealed audiotape recordings (about thirty hours), questionnaires, self-reported individual difference personality measures, and various interviews. Some of these measures were coded for quantitative analyses, and some were correlated with outcome measures.

The data analyses present a number of problems in their interpretation: the sample size was relatively small; the recordings were selective and not comprehensive because of our limited budget and staff, and because of the strategic decision to focus on daily events of high interest (such as counts, meals, visitors, and parole hearings). In addition, the causal directions are uncertain because of the dynamic interplay among guards and prisoners within and across guard shifts. The quantitative data analysis of individual behavior is confounded by the obvious fact of the complex interactions of persons, groups, and time-based effects. In addition, unlike traditional experiments, we did not have a control group of comparable volunteers who did not undergo the experimental treatment of being a mock prisoner or mock guard but were given various pre–post assessments. We did not do so because we thought about our design as more a demonstration of a phenomenon, like Milgram’s original obedience study, than as an experiment to establish causal associations. We imagined doing such control-versus-experimental group comparisons in future research if we obtained any interesting findings from this first exploratory investigation. Thus, our simple independent variable was only the main effect of the treatment of guard-versus-prisoner status.

Nevertheless, some clear patterns emerged that amplify the qualitative narrative I have presented thus far. These findings offer some interesting insights into the nature of this psychologically compelling environment and of the young men who were tested by its demands. Full details of the operational scoring of these measures and their statistical significance is available in the scientific article published in the

International Journal of Criminology and Penology2 and on the website www.prisonexp.org.

Personality Measures

Three kinds of measures of individual differences among the participants were administered when they came in for their pre-experiment assessment a few days prior to the start of the study. These measures were the F-Scale of authoritarianism, the Machiavellian Scale of interpersonal manipulation strategies, and the Comrey Personality Scales.

The F-Scale.

3 On this measure of rigid adherence to conventional values and a submissive, uncritical attitude toward authority, there was no statistically significant difference between the mean score of the guards (4.8) and that of the prisoners (4.4)—before they were divided into the two roles. However, a fascinating finding emerges when we compare the F-Scale scores of the five prisoners who remained for the duration of the study and the five who were released early. Those who endured the authoritarian environment of the SPE scored more than twice (mean = 7.8) as high on conventionality and authoritarianism than their early-released peers (mean = 3.2). Amazingly, when these scores are arranged in rank order from lowest to highest prisoner F-Scale values, a highly significant correlation is found with the number of days of staying in the experiment (correlation coefficient = .90). A prisoner was likely to remain longer and adjust more effectively to the authoritarian prison environment to the extent that he was high in rigidity, adherence to conventional values, and acceptance of authority—the features which characterized our prison setting. To the contrary, the prisoners who handled the pressures least well were the young men who were lowest on these F-Scale traits—which some would say are to their credit.

The Machiavellian Scale.

4 This measure, as its name implies, assesses one’s endorsement of strategies for gaining effective advantage in interpersonal encounters. However, no significant differences were found between the guards’ mean score (7.7) and the slightly higher mean of the prisoners (8.8), nor did this measure predict duration of the stay in prison. We expected that the skill of those high on this trait of manipulating others might be relevant in their daily interactions in this setting, but while two of the prisoners with the highest Machiavellian score were those we judged to have adjusted best to the prison, two others we evaluated as also adjusting well had the lowest Machiavellian scores.

The Comrey Personality Scales.

5 This self-report inventory consists of eight subscales that we used to predict dispositional variations between the guards and prisoners. These personality measures are: Trustworthiness, Orderliness, Conformity, Activity, Stability, Extroversion, Masculinity, and Empathy. On this measure, the average scores of the guards and those of the prisoners were virtually interchangeable; none even approached statistical significance. Furthermore, on every subscale, the group mean fell within the fortieth to sixtieth percentile range of the normative male population reported by Comrey. This finding bolsters the assertion that the personalities of the students in the two different groups could be defined as “normal” or “average.” Craig Haney and Curt Banks did indeed do their preselection task of choosing a sample of student volunteers who were “ordinary men” well. In addition, there were no prior dispositional tendencies that could distinguish those individuals who role-played the guards from those who enacted the prisoner role.

A few interesting, though nonsignificant, differences were found between the prisoners who were released early and those who endured the full catastrophe. The “endurers” scored higher on Conformity (“acceptance of society as it is”), Extroversion, and Empathy (helpfulness, sympathy, generosity) than those who had to be released due to their extreme stress reactions.

If we examine the scores for those individual guards and prisoners that most deviated from the average of their group (by 1.5 standard deviations or more), some curious patterns appear.

First, let’s look at some personality characteristics of particular prisoners. My impression of prisoner Jerry-5486 as “most together” was clearly supported by his being higher than any other prisoner on Stability, with nearly all his other scores very close to the population norm. When he does deviate from the others, it is always in a positive direction. He was also highest in Masculinity (“does not cry easily, not interested in love stories”). Stewart-819, who trashed his cell and caused grief to his cellmates who had to clean up his mess, scored lowest in Orderliness (the extent to which a person is meticulous and concerned with neatness and orderliness). Despite rules to the contrary, he did not care. Guess who scored highest on the measure of Activity (liking physical activity, hard work, and exercise)? Yes, indeed, it was Sarge-2093. Trustworthiness is the belief in the basic honesty and good intentions of others, and Clay-416 took the prize on that dimension. Finally, from the prisoner profiles, who do you suspect got the highest score on “Conformity” (a belief in law enforcement, acceptance of society as it is, and resentment of nonconformity in others)? Who reacted most strongly against Clay-416’s resistance to the guards’ demands? It was none other than our handsome youngster, Hubbie-7258!

Among the guards, there were only a few individual profile scores that were interesting as being “atypical” compared to their peers’. First, we see that the “good guard” John Landry, not his brother Geoff, was highest on Empathy. Guard Varnish was lowest on Empathy and Trustworthiness but highest on concern for neatness and orderliness. He also had the highest Machiavellian score of any guard. Packaged together, that syndrome characterizes the coolly efficient, mechanical, and detached behavior he showed throughout the study.

While these findings suggest that personality measures do predict behavioral differences in some individual cases, we need to be cautious in overgeneralizing their utility in understanding individual behavior patterns in novel settings, such as this one. For example, based on all the measures we examined, Jerry-5486 was the most “supranormal” of the prisoners. However, second in line with personality inventory scores that would qualify him as “most normal” is Doug-8612. His disturbed account of acting and then becoming “crazy” was hardly predictable from his “most normal” pre-experimental status. Moreover, we could find no personality precursors for the difference between the four meanest guards and the others who were less abusive. Not a single personality predisposition could account for this extreme behavioral variation.

Now if we look at the personality scores of the two guards who were clearly the meanest and most sadistic toward prisoners, Hellmann and Arnett, both turned out to be ordinary, average on all but one of the personality dimensions. Where they diverged was on Masculinity. An intuitive personality theorist would seem justified in assuming that Hellmann, our badass “John Wayne,” would top off the scale on Masculinity. Just the opposite was true: he scored lower on Masculinity than any other guard and, for that matter, lower than any prisoner did. In contrast, Arnett scored as the most masculine of all the guards. Psychodynamic analysts would most certainly assume that Hellmann’s cruel, dominating behavior and his invention of homophobic exercises were motivated by a reaction formation against his nonmasculine, possibly latent-homosexual nature. However, before we wax analytically lyrical, I must hasten to add that there has been nothing in his subsequent lifestyle over the past thirty-five years that has characterized this young man as anything but appropriate and normal as a husband, father, businessman, and civic-minded citizen.

Mood Adjective Self-Reports. Twice during the study and immediately after the debriefing session, each of the students completed a checklist of adjectives that they felt best described their current mood state. We combined the mood adjectives into those that reflected negative versus positive moods and separately those that portrayed activity versus passivity. As might well be expected from all we have seen of the state of the prisoners, the prisoners expressed three times as much negative affect as positive and much more negativity overall than did the guards. The guards expressed slightly more negative than positive affect. Another interesting difference between the two groups is the greater fluctuation in the prisoners’ mood states. Over the course of the study, they showed two to three times as much variation in their moods as did the relatively stable guards. On the dimension of activity-passivity, the prisoners tended to score twice as high, indicating twice as much internal “agitation” as the guards. While the prison experience had a negative emotional impact upon both guards and prisoners, the adverse effects upon the prisoners were more profound and unstable.

Comparing the prisoners who stayed to those who were released early, the mood of those who had to be terminated was marked by a decidedly more negative tone: depression and unhappiness. When the mood scales were administered for a third time, just after the subjects were told that the study had been terminated (the early-released subjects returned for the debriefing encounter session), elevated changes in positive moods were evident. All of the now “ex-convicts” selected self-descriptive adjectives that characterized their mood as less negative and much more positive—a decrease in negativity from the initially strong 15.0 to a low of 5.0, while their positivity soared from the initial low of 6.0 up to 17.0. In addition, they now felt less passive than before.

In general, there were no longer any differences on these mood subscales between prisoners released early and those who endured the six days. I am happy to be able to report the vital conclusion that by the end of the study both groups of students had returned to their pre-experiment baselines of normal emotional responding. This return to normality seems to reflect the “situational specificity” of the depression and stress reactions these students experienced while playing their unusual roles.

This last finding can be interpreted in several ways. The emotional impact of the prison experience was transient since the suffering prisoners quickly bounced back to a normal mood base level as soon as the study was terminated. It also speaks to the “normality” of the participants we had so carefully selected, and this bounce-back attests to their resilience. However, the same overall reaction among the prisoners could have come from very different sources. Those who remained were elated by their newfound freedom and the knowledge that they had survived the ordeal. Those who were released early were no longer emotionally distressed, having readjusted while away from the negative situation. Perhaps we can also attribute some of their newly positive reactions to gratification at seeing their fellow prisoners released, thus relieving them of the burden of guilt they may have felt for leaving early while their fellows had to stay on, enduring the ordeal.

Although some guards indicated that they wished the study had continued as planned for another week, as a group they too were glad to see it end. Their mean positivity score more than doubled (from 4.0 to 10.2), and their low negativity score (6.0) got even lower (2.0). Therefore, as a group, they also were able to regain their emotional composure and balance despite their role in creating the horrible conditions in this prison setting. This mood readjustment does not mean that some of these young men were not troubled by what they had done and by their failure to stop abuse, as we noted earlier in their postexperiment reactions and retrospective diaries.

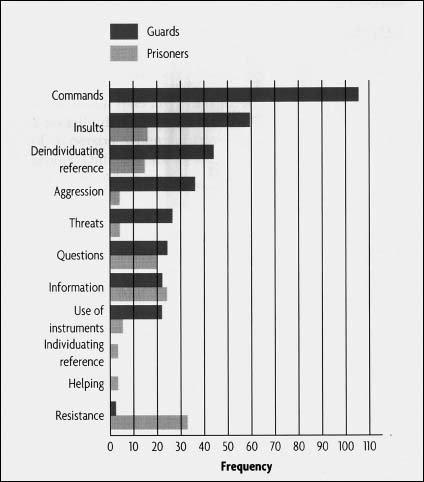

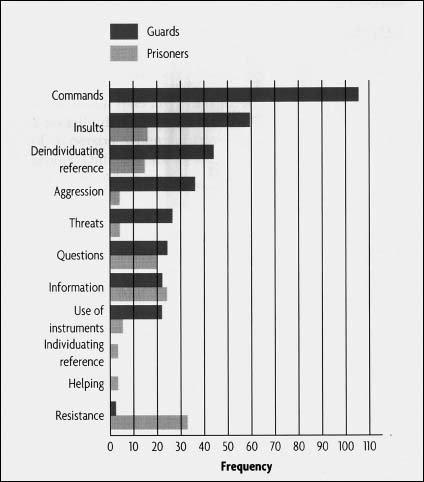

Video Analysis. There were twenty-five relatively discrete incidents identifiable on the tapes of prisoner–guard interactions. Each incident or scene was scored for the presence of ten behavioral (and verbal) categories. Two raters, who had not been involved with the study, independently scored these tapes, and their level of agreement was satisfactory. These categories were: Asking Questions, Giving Commands, Offering Information, Using Individuating Reference (positive) or Deindividuating (negative), Making Threats, Giving Resistance, Helping Others, Using Instruments (for some goal), and Exhibiting Aggression.

As shown in the figure summarizing these results, overall there was an excess of negative, hostile interactions between the guards and prisoners. Assertive activity was largely the prerogative of the guards, while the prisoners generally assumed a relatively passive stance. Most characteristic of the guards across the situations we recorded were the following responses: giving commands, insulting prisoners, deindividualizing prisoners, showing aggression toward prisoners, threatening, and using instruments against them.

GUARD AND PRISONER BEHAVIOR

6

At first, the prisoners resisted the guards, notably in the early days of the study and later, when Clay-416 went on his hunger strike. The prisoners tended to positively individuate others, asked questions of them, gave information to them, and rarely showed the negative behavior toward others that became typical of the dominating guards. Again, this occurred only in the first days of the study. On the other hand, the two most infrequent behaviors we observed over the six days of our study were individuating others and helping others. Only one such incident of helping was recorded—a solitary sign of human concern for a fellow human being occurred between two prisoners.

The recordings also underscore quantitatively what was observed over the course of the study: the guards continually escalated their harassment of the prisoners. If we compare two of the first prisoner–guard interactions during the counts with two of the last, we note that in an equivalent unit of time, no deindividuating references occurred initially, but a robust average of 5.4 occurred in the last counts. Similarly, the guards spoke few deprecating insults initially, only an average of 0.3, but by the last day they degraded the prisoners an average of 5.7 times in the same length of time.

According to the temporal analysis from this video data, what the prisoners did was simply to behave less and less over time. There was a general decrease across all behavioral categories over time. They did little initiating, simply becoming increasingly passive as the days and nights moved numbingly on.

The video analysis also clearly showed that the “John Wayne” night shift was hardest on the prisoners compared to the other two shifts. The behavior of the guards on this tough and cruel shift differed significantly from those that preceded and followed it in the following ways: issuing more commands (an average of 9.3 versus 4.0, respectively, for standardized units of time); giving more than twice as many deprecating insults toward the prisoners (5.2 versus 2.3, respectively). They also resorted more often to aggressively punishing the prisoners than did the guards on the other shifts. The more subtle verbal aggression in Arnett’s shift is not detected in these analyses.

Audio Analysis. From time to time, audio recordings with concealed microphones were made of interviews between one of the staff with prisoners and guards, and of conversations among prisoners taking place in the cells. Nine categories were created to capture the general nature of this verbal behavior. Again, the recordings were classified into these categories by two independent judges, who did so reliably.

In addition to asking questions, giving information, making requests and demands and ordering commands, other categories focused on criticism; positive/negative outlook; positive/negative self-evaluation; individuating/deindividuating references; desire to continue in the study or abort; and intention to act in the future in positive or negative ways.

We were surprised to discover that the guards tended to have nearly as much negative outlook and negative self-regard as did most of the prisoners. In fact, the “good guard” Geoff Landry expressed more negative self-regard than did any prisoner and more general negative affect than all but one participant, namely Doug-8612. Our interviews with prisoners were marked by their general negativity in expressing affect and in their self-regard and intentions (primarily intention to be aggressive and having a negative outlook on their situation).

These interviews showed clear differences in the emotional impact of the experience between the prisoners who remained and those who were released early. We compared the mean number of expressions of negative outlook, negative affect, negative self-regard, and intention to aggress that were made by remaining versus released prisoners (per interview). Prisoners released early expressed expectations that were more negative and had more negative affect, more negative self-regard, and four times as many intentions to aggress as did their fellow prisoners who stuck it out. These interesting trends are close to being statistically significant.

Bugging the cells gave us information about what the prisoners were discussing in private during temporary respites from the counts, the menial work tasks, and other public events. Remember that the three inmates in each cell were initially total strangers. It was only when they were alone in the solitude of their cells that they could get to know one another since no “small talk” was allowed at public times. We assumed that they would seek common ground for relating to one another, given their close quarters and their expectation of interacting for two weeks. We expected to hear them talk about their college lives, majors, vocations, girlfriends, favorite teams, music preferences, hobbies, what they would do for the remainder of the summer once the experiment was over, or maybe what they would do with the money they would earn.

Not at all! Almost none of these expectations were borne out. Fully 90 percent of all conversations among prisoners related to prison issues. Only a mere 10 percent focused on personal or autobiographical exchanges that were not related to the prison experience. The prisoners were most concerned about food, guard harassment, establishing a grievance committee, forging plans of escape, visitors, and the behavior of prisoners in the other cells and those in solitary.

When they had the opportunity to distance themselves temporarily from the harassment by guards and the tedium of their schedules, to transcend the prisoner role and establish their personal identity in a social interaction, they did not do so. The prisoner role dominated all expressions of individual character. The prison setting dominated their outlook and concerns—forcing them into an expanded present temporal orientation. It did not matter whether the presentation of self was under surveillance or free from its glare.

By not sharing their pasts and future expectations, the only thing each prisoner knew about the other prisoners was based on observations of how they were behaving in the present. We know that what they had to see during counts and other menial activities was usually a negative image of one another. That image was all they had upon which to build a personality impression of their peers. Because they focused on the immediate situation, the prisoners also contributed to fostering a mentality that intensified the negativity of their experiences. Generally, we manage to cope with bad situations by compartmentalizing them into a temporal perspective that imagines a better, different future combined with recall of a reassuring past.

This self-imposed intensification of prisoner mentality had an even more damaging consequence: the prisoners began to adopt and accept the negative images that the guards had developed toward them. Half of all reported private interactions between the prisoners could be classified as nonsupportive and noncooperative. Even worse, whenever the prisoners made evaluative statements of, or expressed regard for, their fellow prisoners, 85 percent of the time they were uncomplimentary and deprecating! These frequencies are statistically significant: the greater focus on prison than nonprison topics would occur only one time in a hundred by chance, while the focus on negative attributions of fellow prisoners as opposed to positive or neutral terms would occur by chance only five times in a hundred. This means that such emerging behavioral effects are “real” and not likely to be attributed to random fluctuations in what the prisoners discussed in the privacy of their cells.

By internalizing the oppressiveness of the prison setting in these ways, the prisoners formed impressions of their mates primarily by watching them be humiliated, act like compliant sheep, or carry out mindlessly degrading orders. Without developing any respect for the others, how could they come to have any self-respect in this prison? This last unexpected finding reminds me of the phenomenon of “identification with the aggressor.” The psychologist Bruno Bettelheim

7 used this term to characterize ways in which Nazi concentration camp prisoners internalized the power that was inherent in their oppressors (it was first used by Anna Freud). Bettelheim observed that some inmates acted like their Nazi guards, not only abusing other prisoners but even wearing bits of cast-off SS uniforms. Desperately hoping to survive a hostile, unpredictable existence, the victim senses what the aggressor wants and rather than opposing him, embraces his image and becomes what the aggressor is. The frightening power differential between powerful guards and powerless prisoners is psychologically minimized by such mental gymnastics. One becomes one with one’s enemy—in one’s own mind. This self-delusion prevents realistic appraisals of one’s situation, inhibits effective action, coping strategies, or rebellion, and does not permit empathy for one’s fellow sufferers.

8

Life is the art of being well-deceived; and in order that the deception may succeed it must be habitual and uninterrupted.

—William Hazlitt, “On Pedantry,” The Round Table, 1817

THE SPE’S LESSONS AND MESSAGES

It is time to move from the specific behavioral reactions and personal attributes of these young men who enacted the roles of prisoners and guards to consider some broader conceptual issues raised by this research and its lessons, meaning, and messages.

The Virtue of Science

From one perspective, the SPE does not tell us anything about prisons that sociologists, criminologists, and the narratives of prisoners have not already revealed about the evils of prison life. Prisons can be brutalizing places that invoke what is worst in human nature. They breed more violence and crime than they foster constructive rehabilitation. Recidivism rates of 60 percent and higher indicate that prisons have become revolving doors for those sentenced for criminal felonies. What does the SPE add to our understanding of society’s failed experiment of prisons as its instruments of crime control? I think the answer lies in the experiment’s basic protocol.

In real prisons, defects of the prison situation and those of the people who inhabit it are confounded, inextricably intertwined. Recall my first discussion with the sergeant in the Palo Alto police station wherein I explained the reason we were conducting this research rather than going to a local prison to observe what was going on. This experiment was designed to assess the impact of a simulated prison situation on those who lived in it, both guards and prisoners. By means of various experimental controls, we were able to do a number of things, and draw conclusions, that would not have been possible in real-world settings.

Systematic selection procedures ensured that everyone going into our prison was as normal, average, and healthy as possible and had no prior history of antisocial behavior, crime, or violence. Moreover, because they were college students, they were generally above average in intelligence, lower in prejudice, and more confident about their futures than their less educated peers. Then, by virtue of random assignment, the key to experimental research, these good people were randomly assigned to the role of guard or prisoner, regardless of whatever inclination they might have had to be the other. Chance ruled. Further experimental control involved systematic observation, collection of multiple forms of evidence, and statistical data analyses that together could be used to determine the impact of the experience within the parameters of the research design. The SPE protocol disentangled person from place, disposition from situation, “good apples” from “bad barrels.”

We must acknowledge, however, that all research is “artificial,” being only an imitation of its real-world analogue. Nevertheless, despite the artificiality of controlled experimental research like the SPE, or that of the social psychological studies we will encounter in later chapters, when such research is conducted in sensitive ways that capture essential features of “mundane realism,” the results can have considerable generalizability.

9

Our prison was obviously not a “real prison” in many of its tangible features, but it did capture the central psychological features of imprisonment that I believe are central to the “prison experience.” To be sure, any finding derived from an experiment must raise two questions. First, “Compared to what?” Next, “What is its external validity—the real-world parallels that it may help to explain?” The value of such research typically lies in its ability to illuminate underlying processes, identify causal sequences, and establish the variables that mediate an observed effect. Moreover, experiments can establish causal relationships that if statistically significant cannot be dismissed as chance connections.

The pioneering theorist-researcher in social psychology Kurt Lewin argued decades ago for a science of experimental social psychology. Lewin asserted that it is possible to abstract significant issues from the real world conceptually and practically and test them in the experimental laboratory. With well-designed studies and carefully executed manipulations of independent variables (the antecedent factors used as behavioral predictors), he thought, it was possible to establish certain causal relationships in ways that were not possible in field or observational studies. However, Lewin went further to advocate using that knowledge to effect social change, using research-based evidence to understand as well as attempt to change and improve society and human functioning.

10 I have tried to follow his inspiring lead.

Guard Power Transformations

Our sense of power is more vivid when we break a man’s spirit than when we win his heart.

—Eric Hoffer, The Passionate State of Mind (1954)

Some of our volunteers who were randomly assigned to be guards soon came to abuse their newfound power by behaving sadistically—demeaning, degrading, and hurting the “prisoners” day in and night out. Their actions fit the psychological definition of evil proposed in

chapter 1. Other guards played their role in tough, demanding ways that were not particularly abusive, but they showed little sympathy for the plight of the suffering inmates. A few guards, who could be classified as “good guards,” resisted the temptation of power and were at times considerate of the prisoners’ condition, doing little things like giving one an apple, another a cigarette, and so on.

Although vastly different from the SPE in the extent of its horror and complexity of the system that spawned and sustained it, there is one interesting parallel between the Nazi SS doctors involved in the death camp at Auschwitz and our SPE guards. Like our guards, those doctors could be categorized as falling into three groups. According to Robert Jay Lifton in

Nazi Doctors, there were “zealots who participated eagerly in the extermination process and even did ‘extra work’ on behalf of killing; those who went about the process more or less methodically and did no more or no less than they felt that they had to do; and those who participated in the extermination process only reluctantly.”

11

In our study, being a good guard who did his job reluctantly meant “goodness by default.” Doing minor nice deeds for the prisoners simply contrasted with the demonic actions of their shift mates. As noted previously, none of them ever intervened to prevent the “bad guards” from abusing the prisoners; none complained to the staff, left their shift early or came to work late, or refused to work overtime in emergencies. Moreover, none of them even demanded overtime pay for doing tasks they may have found distasteful. They were part of the “Evil of Inaction Syndrome,” which will be discussed more fully later.

Recall that the best good guard, Geoff Landry, shared the night shift with the worst guard, Hellmann, and he never once made any attempt to get him to “chill out,” never reminded him that this was “just an experiment,” that there was no need to inflict so much suffering on the kids who were just role-playing prisoners. Instead, as we have seen from his personal accounts, Geoff simply suffered in silence—along with the prisoners. Had he energized his conscience into constructive action, this good guard might have had a significant impact in mitigating the escalating abuse of the prisoners on his shift.

In my many years of experience teaching at a variety of universities, I have found that most students are not concerned with power issues because they have enough to get by in their world, where intelligence and hard work get them to their goals. Power is a concern when people either have a lot of it and need to maintain it or when they have not much power and want to get more. However, power itself becomes a goal for many because of all the resources at the disposal of the powerful. The former statesman Henry Kissinger described this lure as “the aphrodisiac of power.” That lure attracts beautiful young women to ugly, old, but powerful men.

Prisoner Pathologies

Wherever anyone is against his will, that is to him a prison.

—Epictetus, Discourses, second century a.d.

Our initial interest was not so much in the guards as in how those assigned the prisoner role would adapt to their new lowly, powerless status. Having spent the summer enmeshed in the psychology of imprisonment course I had just cotaught at Stanford, I was primed to be on their side. Carlo Prescott had filled us with vivid tales of abuse and degradation at the hands of guards. From other former prisoners, we heard firsthand the horror stories of prisoners sexually abusing other prisoners and gang wars. Thus, Craig, Curt, and I were privately pulling for the prisoners, hoping that they would resist any pressures the guards could muster against them and maintain their personal dignity despite the external signs of inferiority they were forced to wear. I could imagine myself a Paul Newman kind of wisely resistant prisoner, as portrayed in the movie

Cool Hand Luke. I could never imagine myself as his jailor.

12

We were pleased when the prisoners rebelled so soon, challenging the hassling of the menial tasks the guards assigned them, the arbitrary enforcement of rules, and the exhausting count lineups. Their expectations about what they would be doing in the “study of prison life” to which our newspaper ad had recruited them had been violated. They had anticipated a little menial labor for a few hours mixed with time to read, relax, play some games, and meet new people. That, in fact, was what our preliminary agenda called for—before the prisoners’ rebellion and before the guards took control of matters. We had even planned to have movie nights for them.

The prisoners were particularly upset by the constant abuse rained on them day and night, the lack of privacy and relief from staff surveillance, the arbitrary enforcement of rules and random punishments, and being forced to share their barren, cramped quarters. When the guards turned to us for help after the rebellion started, we backed off and made it clear that their decisions would prevail. We were observers who did not want to intrude. I was not yet fully submerged in the superintendent’s mentality at that early stage; rather, I was acting as the principal investigator, interested in data on how these mock guards would react to this emergency.

The breakdown of Doug-8612, coming so soon after he had helped to engineer a rebellion, caught us all off guard, if you will excuse the pun. We were all shaken by his shrill voice screaming opposition to everything that was wrong in the way the prisoners were being treated. Even when he shouted, “It’s a fucking simulation, not a prison, and fuck Dr. Zimbargo!” I could not help but admire his spunk. We could not bring ourselves to believe that he was really suffering as much as he seemed to be. Recall my conversation with him when he first wanted to be released and I invited him to consider the option of becoming a “snitch” in return for a hassle-free time as a prisoner.

Recall further that Craig Haney had made the difficult decision to deal with Doug-8612’s sudden breakdown by releasing him after only thirty-six hours into the experiment.

As experimenters, none of us had predicted an event like this, and, of course, we had devised no contingency plan to cover it. On the other hand, it was obvious that this young man was more disturbed by his brief experience in the Stanford Prison than any of us had expected. . . . So, I decided to release Prisoner 8612, going with the ethical, humanitarian decision over the experimental one.

How did we explain this violation of our expectations that no one could have such a severe stress reaction so quickly? Craig remembers our wrong-headed causal attribution:

We quickly seized on an explanation that felt as natural as it was reassuring—he must have broken down because he was weak or had some kind of defect in his personality that accounted for his oversensitivity and overreaction to the simulated prison conditions! In fact, we worried that there had been a flaw in our screening process that had allowed a “damaged” person somehow to slip through undetected. It was only later that we appreciated this obvious irony: we had “dispositionally explained” the first truly unexpected and extraordinary demonstration of situational power in our study by resorting to precisely the kind of thinking we had designed the study to challenge and critique.

13

Let’s go back and review the final reactions to this experience by Doug-8612 to appreciate his level of confusion at that time:

“I decided I want out, and then I went to talk to you guys and everything, and you said ‘No’ and you bullshitted me and everything, and I came back and I realized you were bullshitting me, and that made me mad, so I decided I’m getting out and I was going to do anything, and I made up several schemes whereby I could get out. The easiest one and that wouldn’t hurt anybody or hurt any equipment was to just act mad or upset, so I chose that one. When I was in the Hole, I purposely kind of built it up and I knew that when I went to talk with Jaffe, I didn’t want to release the energy in the Hole, I wanted to release in front of Jaffe, so I knew I’d get out, and then, even while I was being upset, I was manipulating and I was being upset, you know—how could you act upset unless you

were upset . . . it’s like a crazy person can’t act crazy unless he really is kinda crazy, you know? I don’t know whether I was upset or whether I was induced. . . . I was mad at the black guy, and what was his name, Carter? Something like that and you, Dr. Zimbardo, for making the contract like I was a serf or something . . . and the way you played with me afterwards, but what can you do, you had to do that, your people had to do it in an experiment.”

14

WHY SITUATIONS MATTER

Within certain powerful social settings, human nature can be transformed in ways as dramatic as the chemical transformation in Robert Louis Stevenson’s captivating fable of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The enduring interest in the SPE over many decades comes, I think, from the experiment’s startling revelation of “transformation of character”—of good people suddenly becoming perpetrators of evil as guards or pathologically passive victims as prisoners in response to situational forces acting on them.

Good people can be induced, seduced, and initiated into behaving in evil ways. They can also be led to act in irrational, stupid, self-destructive, antisocial, and mindless ways when they are immersed in “total situations” that impact human nature in ways that challenge our sense of the stability and consistency of individual personality, of character, and of morality.

15

We want to believe in the essential, unchanging goodness of people, in their power to resist external pressures, in their rational appraisal and then rejection of situational temptations. We invest human nature with God-like qualities, with moral and rational faculties that make us both just and wise. We simplify the complexity of human experience by erecting a seemingly impermeable boundary between Good and Evil. On one side are Us, Our Kin, and Our Kind; on the other side of that line we cast Them, Their Different Kin, and Other Kind. Paradoxically, by creating this myth of our invulnerability to situational forces, we set ourselves up for a fall by not being sufficiently vigilant to situational forces.

The SPE, along with much other social science research (presented in chapters 12 and 13), reveals a message we do not want to accept: that most of us can undergo significant character transformations when we are caught up in the crucible of social forces. What we imagine we would do when we are outside that crucible may bear little resemblance to who we become and what we are capable of doing once we are inside its network. The SPE is a clarion call to abandon simplistic notions of the Good Self dominating Bad Situations. We are best able to avoid, prevent, challenge, and change such negative situational forces only by recognizing their potential power to “infect us,” as it has others who were similarly situated. It is well for us to internalize the significance of the recognition by the ancient Roman comedy writer Terence that “Nothing by humans is alien to me.”

This lesson should have been taught repeatedly by the behavioral transformation of Nazi concentration camp guards, and of those in destructive cults, such as Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple, and more recently by the Japanese Aum Shinrikyo cult. The genocide and atrocities committed in Bosnia, Kosovo, Rwanda, Burundi, and recently in Sudan’s Darfur region also provide strong evidence of people surrendering their humanity and compassion to social power and abstract ideologies of conquest and national security.

Any deed that any human being has ever committed, however horrible, is possible for any of us—under the right or wrong situational circumstances. That knowledge does not excuse evil; rather, it democratizes it, sharing its blame among ordinary actors rather than declaring it the province only of deviants and despots—of Them but not Us.

The primary simple lesson the Stanford Prison Experiment teaches is that

situations matter. Social situations can have more profound effects on the behavior and mental functioning of individuals, groups, and national leaders than we might believe possible. Some situations can exert such powerful influence over us that we can be led to behave in ways we would not, could not, predict was possible in advance.

16

Situational power is most salient in novel settings, those in which people cannot call on previous guidelines for their new behavioral options. In such situations the usual reward structures are different and expectations are violated. Under such circumstances, personality variables have little predictive utility because they depend on estimations of imagined future actions based on characteristic past reactions in familiar situations—but rarely in the kind of new situation currently being encountered, say by a new guard or prisoner.

Therefore, whenever we are trying to understand the cause of any puzzling, unusual behavior, our own or that of others, we should start out with a situational analysis. We should yield to dispositional analyses (genes, personality traits, personal pathologies, and so on) only when the situationally based detective work fails to make sense of the puzzle. My colleague Lee Ross adds that such an approach invites us to practice “attributional charity.” That means we start not by blaming the actor for the deed but rather, being charitable, we first investigate the scene for situational determinants of the act.

However, attributional charity is easier said than practiced because most of us have a powerful mental bias—the “fundamental attribution error”—that prevents such reasonable thinking.

17 Societies that promote individualism, such as the United States and many other Western nations, have come to believe that dispositions matter more than situations. We overemphasize personality in explaining any behavior while concurrently underemphasizing situational influences. After reading this book, I hope you will begin to notice how often you see this dual principle in action in your own thinking and in decisions of others. Let’s consider next some of the features that make situations matter, as illustrated in our prison study.

The Power of Rules to Shape Reality

Situational forces in the SPE combined a number of factors, none of which was very dramatic alone but that together were powerful in their aggregation. One of the key features was the power of rules. Rules are formal, simplified ways of controlling informal complex behavior. They work by externalizing regulations, by establishing what is necessary, acceptable, and rewarded and what is unacceptable and therefore punished. Over time, rules come to have an arbitrary life of their own and the force of legal authority even when they are no longer relevant, are vague, or change with the whims of the enforcers.

Our guards could justify most of the harm they did to the prisoners by referencing “the Rules.” Recall, for example, the agony the prisoners had to endure to memorize the set of seventeen arbitrary rules that the guards and the warden had invented. Consider also the misuse of Rule 2 about eating at mealtimes to punish Clay-416 for refusing to eat his filthy sausages.

Some rules are essential for the effective coordination of social behavior, such as audiences listening while performers speak, drivers stopping at red traffic lights, and people not cutting into queues. However, many rules are merely screens for dominance by those who make them or those charged with enforcing them. Naturally, the last rule, as with the SPE rules, always includes punishment for violation of the other rules. Therefore, there must be someone or some agency willing and able to administer such punishment, ideally doing so in a public arena that can serve to deter other potential rule breakers. The comedian Lenny Bruce had a funny routine describing the development of rules to govern who could and could not throw shit over fences onto a neighbor’s property. He described the creation of police as guardians of the “no-shit-in-my-backyard” rule. The rules and their enforcers are inherent in situational power. However, it is the System that hires the police and creates the prisons for convicted rule breakers.

When Roles Become Real

Once you put a uniform on, and are given a role, I mean, a job, saying “your job is to keep these people in line,” then you’re certainly not the same person if you’re in street clothes and in a different role. You really become that person once you put on the khaki uniform, you put on the glasses, you take the nightstick, and you act the part. That’s your costume and you have to act accordingly when you put it on.

—Guard Hellmann

When actors enact a fictional character, they often have to take on roles that are dissimilar to their sense of personal identity. They learn to talk, walk, eat, and even to think and to feel as demanded by the role they are performing. Their professional training enables them to maintain the separation of character and identity, to keep self in the background while playing a role that might be dramatically different from who they really are. However, there are times when even for some trained professionals those boundaries blur and the role takes over even after the curtain comes down or the camera’s red light goes off. They become absorbed in the intensity of the role and their intensity spills over to direct their offstage life. The play’s audience ceases to matter because the role is now within the actor’s mind.

A fascinating example of this effect of a dramatic role becoming a “tad too real” comes from the British television series

The Edwardian Country House. Nineteen people, chosen from some eight thousand applicants, lived the lives of British servants working on a posh country estate in this “reality television” drama. Although the person chosen to play the head butler in charge of the staff expected to follow the period’s rigidly hierarchical standards of behavior, he was “frightened” by the ease with which he became an autocratic master. This sixty-five-year-old architect was not prepared to slip so readily into a role that allowed him to exercise absolute power over a household of underservants whom he bossed: “Suddenly you realize that you don’t have to speak. All I had to do was lift my finger up and they would keep quiet. And that is a frightening thought—it’s appalling.” A young woman who played the role of a housemaid but who in real life is a tourist information officer, began to feel like an invisible person. She described how she and the others so quickly adapted to their subservient role: “I was surprised, then scared at the way we all became squashed. We learned so quickly that you don’t answer back, and you feel subservient.”

18

Typically, roles are tied to specific situations, jobs, and functions, such as being a professor, doorman, cab driver, minister, social worker, or porn actor. They are enacted when one is in that situation—at home, school, church, or factory, or onstage. Roles can usually be set aside when one returns to his or her “normal” other life. Yet some roles are insidious, are not just scripts that we enact only from time to time; they can become who we are most of the time. They are internalized even as we initially acknowledge them as artificial, temporary, and situationally bound. We become father, mother, son, daughter, neighbor, boss, worker, helper, healer, whore, soldier, beggar man, thief, and many more.

To complicate matters further, we all must play multiple roles, some conflicting, some that may challenge our basic values and beliefs. As in the SPE, what starts out as the “just playing a role” caveat to distinguish it from the real individual can have a profound impact when the role behavior gets rewarded. The “class clown” gets attention he can’t get from displaying special academic talents but then is never again taken seriously. Even shyness can be a role initially enacted to avoid awkward social encounters, a situational awkwardness, and when practiced enough the role morphs into a shy person.

Just as discomfiting, people can do terrible things when they allow the role they play to have rigid boundaries that circumscribe what is appropriate, expected, and reinforced in a given setting. Such rigidity in the role shuts off the traditional morality and values that govern their lives when they are in “normal mode.” The ego-defense mechanism of compartmentalization allows us to mentally bind conflicting aspects of our beliefs and experiences into separate chambers that prevent interpretation or cross talk. A good husband can then be a guiltless adulterer; a saintly priest can then be a lifelong pederast; a kindly farmer can then be a heartless slave master. We need to appreciate the power that role-playing can have in shaping our perspectives, for better as well as for worse, as when adopting the teacher or nurse role translates into a life of sacrifice for the good of one’s students and patients.

Role Transitions from Healer to Killer

The worst-case scenario was the Nazi SS doctors who were assigned the role of selecting concentration camp inmates for extermination or for “experiments.” They were socialized away from their usual healing role into the new role, assisting with killing, by means of a group consensus that their behavior was necessary for the common good, which led them to adopt several extreme psychological defenses against facing the reality of their complicity in the mass murder of Jews. Again we turn to the detailed account of these processes by social psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton.

When a new doctor would come on the scene and be initially horrified by what he witnessed, he would ask:

“How can these things be done here?” Then there was something like a general answer . . . which clarified everything. What is better for him [the prisoner]—whether he croaks [verreckt] in shit or goes to heaven in [a cloud of] gas? And that settled the whole matter for the initiates [Eingeweihten].

Mass killing was the unyielding fact of life to which everyone was expected to adapt.

Framing the genocide of the Jews as the “Final Solution” (Endlösung) served a dual psychological purpose: “it stood for mass murder without sounding or feeling like it; and it kept the focus primarily on problem solving.” It transformed the whole matter into a difficult problem that had to be solved by whatever means were necessary to achieve a pragmatic goal. The intellectual exercise deleted emotions and compassion from the doctor’s daily rounds.

However, their job in selecting inmates for annihilation was both so “onerous, so associated with extraordinary evil” that these highly educated doctors had to utilize every possible psychological defense against avoiding the reality of their complicity in these murders. For some, “psychic numbing,” detaching affect from cognition, became the norm; for others there was a schizophrenic solution of “doubling.” The polarities of cruelty and decency in the same doctor at different times would “call forth two radically different psychological constellations within the self: one based on ‘values generally accepted’ and the education and background of a ‘normal person’; the other based on ‘this [Nazi-Auschwitz] ideology with values quite different from those generally accepted.’” These twin tendencies shifted back and forth from day to day.

19

Reciprocal Roles and Their Scripts

It is also the case that some roles require reciprocal partnerships; for the guard role to have meaning, somebody has to play prisoner. One can’t be a prisoner unless someone is willing to be the guard. In the SPE, no explicit training was required for the performance of roles, no manual of best practices. Recall on Day 1 the awkwardness of the guards and the prisoners’ frivolity as each were feeling out their new strange roles. However, very soon, our participants were able to slip easily into their roles as the nature of the power differential at the base of the guard–prisoner symbiosis became clearer.

The initial script for guard or prisoner role-playing came from the participants’ own experiences with power and powerlessness, of their observation of interactions between parents (traditionally, Dad is guard, Mom the prisoner), of their responses to the authority of doctors, teachers, and bosses, and finally from the cultural inscriptions written upon them by movie accounts of prison life. Society had done the training for us. We had only to record the extent of their improvisation with the roles they played—as our data.

There is abundant evidence that virtually all of our participants at one time or another experienced reactions that went well beyond the surface demands of role-playing and penetrated the deep structure of the psychology of imprisonment. Initially, some of the guards’ reactions were probably influenced by their orientation, which outlined the kind of atmosphere we wished to create in order to simulate the reality of imprisonment. But whatever general demands those stage settings may have outlined for them to be “good actors,” they should not have been operative when the guards were in private or believed that we were not observing them.

Postexperimental reports told us that some guards had been especially brutal when they were alone with a prisoner on a toilet run outside the Yard, pushing him into a urinal or against a wall. The most sadistic behaviors we observed took place during the late-night and early-morning shifts, when, as we learned, the guards didn’t believe that we were observing or recording them, in a sense, when the experiment was “off.” In addition, we have seen that guard abuse of prisoners escalated to new, higher levels each day despite the prisoners’ nonresistance and the obvious signs of their deterioration as the full catastrophe of imprisonment was achieved. In one taped interview, a guard laughingly recalled apologizing for having pushed a prisoner on the first day, but by Day 4, he thought nothing of shoving them around and humiliating them.

Craig Haney’s discerning analysis reveals the transformation in the power infusing the guards. Consider this encounter with one of them that took place after only a few days into the study:

Just as with the prisoners, I also had interviewed all of [the guards] before the experiment began and felt I had gotten to know them as individuals, albeit only briefly. Perhaps because of this, I really felt no hostility toward them as the study proceeded and their behavior became increasingly extreme and abusive. But it was obvious to me that because I insisted on talking privately with the prisoners—ostensibly “counseling” them, and occasionally instructed the guards to refrain from their especially harsh and gratuitous mistreatment, they now saw me as something of a traitor. Thus, describing an interaction with me, one of the guards wrote in his diary: “The psychologist rebukes me for handcuffing and blindfolding a prisoner before leaving the (counseling) office, and I resentfully reply that it is both necessary (for) security and my business anyway.” Indeed, he had told me off. In a bizarre turn of events, I was put in my place for failing to uphold the emerging norms of a simulated environment I had helped to create by someone whom I had randomly assigned to his role.

20

In considering the possible biasing of the guard orientation, we are reminded that the prisoners had no orientation at all. What did they do when they were in private and could escape the oppression they repeatedly experienced on the Yard? Rather than getting to know one another and discussing nonprison realities, we learned that they obsessed about the vicissitudes of their current situation. They embellished their prisoner role rather than distancing from it. So, too, with our guards: information we gathered about them when they were in their quarters preparing to enter or leave a shift reveals that they rarely exchanged personal, nonprison information. Instead, they talked about “problem prisoners,” upcoming prison issues, reactions to our staff—never the usual guy stuff that college students might have been expected to share during a break. They did not tell jokes, laugh, or reveal any personal emotion to their peers, which they easily could have done to lighten the situation or distance themselves from the role. Recall Christina Maslach’s earlier description of the transformation of the sweet, sensitive young man she had just met into the brutish John Wayne once he was in uniform and in his power spot on the Yard.

Adult Role-Playing in the SPE

I want to add two final points about the power of roles and the use of roles to justify transgression before moving to our final lessons. Let’s go beyond the roles our volunteers played to recall the roles played to the hilt by the visiting Catholic priest, the head of our Parole Board, the public defender, and the parents on Visiting Nights. The parents not only accepted our show of the prison situation as benign and interesting rather than hostile and destructive, but they allowed us to impose a set of arbitrary rules on them, as we had done to their children, to constrain their behavior. We counted on their playing the embedded roles of conforming, law-abiding, middle-class citizens who respect authority and rarely challenge the system directly. Similarly, we knew that our middle-class prisoners were unlikely to jump the guards directly even when they were desperate and outnumbered them by as much as nine to two, when a guard was off the Yard. Such violence was not part of their learned role behavior, as it might have been with lower-class participants, who would be more likely to take matters into their own hands. There was not even evidence that the prisoners even fantasized such physical attacks.

The reality of any role depends on the support system that demands it and keeps it in bounds, not allowing alternate reality to intrude. Recall that when the mother of Prisoner Rich-1037 complained about his sad state, I spontaneously activated my Institutional Authority role and challenged her observation, implying that there must have been a personal problem with 1037, not an operational problem with our prison.

In retrospect, my role transformation from usually compassionate teacher to data-focused researcher to callous prison superintendent was most distressing. I did improper or bizarre things in that new, strange role, such as undercutting this mother’s justified complaints and becoming agitated when the Palo Alto police officer refused my request to move our prisoners to the city jail. I think that because I so fully adopted the role it helped to make the prison “work” as well as it did. However, by adopting that role, with its focus on the security and maintenance of “my prison,” I failed to appreciate the need to terminate the experiment as soon as the second prisoner went over the edge.

Roles and Responsibility for Transgressions

To the extent that we can both live in the skin of a role and yet be able to separate ourselves from it when necessary, we are in a position to “explain away” our personal responsibility for the damage we cause by our role-based actions. We abdicate responsibility for our actions, blaming them on that role, which we convince ourselves is alien to our usual nature. This is an interesting variant of the Nuremberg Trial defense of the Nazi SS leaders: “I was only following orders.” Instead the defense becomes “Don’t blame me, I was only playing my role at that time in that place—that isn’t the real me.”

Remember Hellmann’s justification for his abusive behavior toward Clay-416 that he described in their television interview. He argued that he had been conducting “little experiments of my own” to see how far he could push the prisoners so that they might rebel and stand up for their rights. In effect, he was proposing that he had been mean to stimulate them to be good; their rebellion would be his primary reward for being so cruel. Where is the fallacy in this post hoc justification? It can be readily exposed in how he handled the sausage rebellion by Clay-416 and Sarge’s “bastard” rebellion; not with admiration for their standing up for rights or principles but rather with rage and more extreme abuse. Here Guard Hellmann was using the full power of being the ultimate guard, able to go beyond the demands of the situation to create his own “little experiment” to satisfy his personal curiosity and amusement.

In a recent interview with a reporter from the

Los Angeles Times on a retrospective investigation of the aftermath of the SPE, Hellmann and Doug-8612 both offered the same reasoning for why they acted as they did, the one being “cruel,” the other “crazy”—they were merely

acting those roles to please Zimbardo.

21 Could be? Maybe they were acting new parts in the Japanese movie

Roshomon, where everyone has a different view of what really happened.

Anonymity and Deindividuation

In addition to the power of rules and roles, situational forces mount in power with the introduction of uniforms, costumes, and masks, all disguises of one’s usual appearance that promote anonymity and reduce personal accountability. When people feel anonymous in a situation, as if no one is aware of their true identity (and thus that no one probably cares), they can more easily be induced to behave in antisocial ways. This is especially so if the setting grants permission to enact one’s impulses or to follow orders or implied guidelines that one would usually disdain. Our silver reflecting sunglasses were one such tool for making the guards, the warden, and me seem more remote and impersonal in our dealings with the prisoners. Their uniforms gave the guards a common identity, as did the necessity of referring to them in the abstract as, “Mr. Correctional Officer.”

A body of research (to be explored in a later chapter) documents the excesses to which deindividuation facilitates violence, vandalism, and stealing in adults as in children—when the situation supports such antisocial actions. You may recognize this process in literature as William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. When all members of a group of individuals are in a deindividuated state, their mental functioning changes: they live in an expanded-present moment that makes past and future distant and irrelevant. Feelings dominate reason, and action dominates reflection. In such a state, the usual cognitive and motivational processes that steer their behavior in socially desirable paths no longer guide people. Instead, their Apollonian rationality and sense of order yield to Dionysian excess and even chaos. Then it becomes as easy to make war as to make love, without considering the consequences

I am reminded of a Vietnamese saying, attributed to the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh: “in order to fight each other, baby chicks of the same mother hen paint their faces different colors.” It is a quaint way to describe the role of deindividuation in facilitating violence. It is worth noticing, as we shall see, that one of the guards in the infamous Tier 1A at Abu Ghraib’s torture center painted his face silver and black in the pattern of the rock group Insane Clown Posse, while he was on duty and posed for one of the many photos that documented prisoner abuse. We will have much more to say later about deindividuation processes as they contributed to the Abu Ghraib abuses.

Cognitive Dissonance That Rationalizes Evil

An interesting consequence of playing a role publicly that is contrary to one’s private beliefs is the creation of cognitive dissonance. When there is a discrepancy between our behavior and beliefs, and when actions do not follow from relevant attitudes, a condition of cognitive dissonance is created. Dissonance is a state of tension that can powerfully motivate change either in one’s public behavior or in one’s private views in efforts to reduce the dissonance. People will go to remarkable lengths to bring discrepant beliefs and behavior into some kind of functional coherence. The greater the discrepancy, the stronger the motivation to achieve consonance and the more extreme changes we can expect to see. There is little dissonance if you harm someone when you have a lot of good reasons—your life was being threatened, it was part of your job as a soldier, you were ordered to act by a powerful authority, or you were given ample rewards for an action that was contrary to your pacifist beliefs.

Oddly enough, the dissonance effect becomes

greater as the justification for such behavior

decreases, for instance, when a repugnant action is carried out for little money, without threat, and with only minimally sufficient justification or inadequate rationale provided for the action. Dissonance mounts, and the attempts to reduce it are greatest, when the person has a sense of free will or when she or he does not notice or fully appreciate the situational pressures urging enactment of the discrepant action. When the discrepant action has been public, it cannot be denied or modified. Thus, the pressure to change is exerted on the softer elements of the dissonance equation, the internal, private elements—values, attitudes, beliefs, and even perceptions. An enormous body of research supports such predictions.

22

How could dissonance motivate the changes we observed in our SPE guards? They had freely volunteered to work long, hard shifts for a small wage of less than $2 an hour. They were given minimal direction on how to play their difficult role. They had to sustain the role consistently over eight-hour work shifts for days and nights whenever they were in uniform, on the Yard, or in the presence of others, whether prisoners or parents or other visitors. They had to return to that role after sixteen-hour breaks from the SPE routine when they were off duty. Such a powerful source of dissonance was probably a major cause for internalizing the public role behaviors and for providing private supporting cognitive and affective response styles that made for the increasingly assertive and abusive behavior over time.

There is more. Having made the commitment to some action dissonant with their personal beliefs, guards felt great pressure to make sense of it, to develop reasons why they were doing something contrary to what they really believed and what they stood for morally. Sensible human beings can be deceived into engaging in irrational actions under many disguised dissonance commitment settings. Social psychology offers ample evidence that when that happens, smart people do stupid things, sane people do crazy things, and moral people do immoral things. After they have done them, they offer “good” rationalizations of why they did what they cannot deny having done. People are less rational than they are adept at rationalizing—explaining away discrepancies between their private morality and actions contrary to it. Doing so allows them to convince themselves and others that rational considerations guided their decision. They are insensitive to their own strong motivation to maintain consistency in the face of such dissonance.

The Power of Social Approval

Typically, people are also unaware of an even stronger force playing on the strings of their behavioral repertoire: the need for social approval. The need to be accepted, liked, and respected—to seem normal and appropriate, to fit in—is so powerful that we are primed to conform to even the most foolish and outlandish behaviors that strangers tell us is the right way to act. We laugh at the many Candid Camera episodes that reveal this truth, but rarely do we notice the times we ourselves are the Candid Camera “stars” in our own lives.

In addition to the dissonance effects, pressures to conform were also operative on our guards. Group pressure from other guards placed significant importance on being a “team player,” conforming to an emergent norm that demanded dehumanizing the prisoners in various ways. The good guard was a group deviant, and he suffered in silence by being outside the socially rewarding circle of the other guards on his shift. The tough guard on each shift was emulated by at least one other guard on each shift.

THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF REALITY

The power that the guards assumed each time they donned their military-style uniforms was matched by the powerlessness the prisoners felt when wearing their wrinkled smocks with ID numbers sewn on their fronts. The guards had billy clubs, whistles, and sunglasses that disguised their eyes; the prisoners had a chained ankle and a stocking cap to contain their long hair. These situational differences were not inherent in the cloth or the hardware; rather, the source of their power is to be found in the psychological material that went into each group’s subjective constructions of the meaning of these uniforms.

To understand how much situations matter, we need to discover the ways in which any given behavioral setting is perceived and interpreted by the people acting within it. It is the meaning that people assign to various components of the situation that creates its social reality. Social reality is more than a situation’s physical features. It is the way actors view their situation, their current behavioral stage, which engages a variety of psychological processes. Such mental representations are beliefs that can modify how any situation is perceived, usually to make it fit or be assimilated into the actor’s expectations and personal values.

Such beliefs create expectations, which in turn can gain strength when they become self-fulfilling prophecies. For example, in a famous experiment (by the psychologist Robert Rosenthal and the school principal Lenore Jacobson), when teachers were led to believe that certain children in their elementary school classes were “late bloomers,” those children actually came to excel academically—even though researchers had chosen their names at random.

23 The teachers’ positive conceptions of the latent talent of these children fed back to modify their behavior toward these children in ways that fostered the children’s enhanced academic performance. Thus, this group of ordinary pupils proved the “Pygmalion Effect” by becoming what they were expected to be—academically outstanding. Sadly, the opposite is likely to occur even more frequently when teachers expect poor performance from certain kinds of pupils—from minority backgrounds or in some classes even from male students. Teachers then unconsciously treat them in ways that validate those negative stereotypes, and those students performing less well than they are capable.