Prisons may be the emblematic structures of disciplinary power, as Foucault has taught us, but they are also spaces that belong to the state. As part of the penal apparatus of the state, they reveal how the state performs and reproduces itself through the exercise of the sovereign right to punish. The notoriety of Turkish prisons is therefore a transparent reflection of the authoritarian and repressive nature of Turkey’s state tradition. Kemalism, named after the founder of the republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, as the official republican ideology of the regime, plays an indispensable role in determining the contours of the dominant tradition of statecraft. The constitutive features of Kemalism are important as they make up the parameters by which the state defines itself, perceives its unity, and asserts itself as an actor on the political stage.

In the Turkish tradition of statecraft, constantly worried about its hard-won sovereignty and unity, the identification of internal threats to security, real or perceived, have always occupied a privileged place. Intolerant toward dissent, the state has more or less continuously pursued a proactive and vigilant policy of criminalizing and punishing its radical challengers. Hence, even though their numbers have ebbed and flowed, political prisoners have always had a continuous and unique presence in Turkish politics as a direct outcome of the security interests of the state. The situation of political prisoners can therefore be considered to be the barometer of Turkish democracy.

Identification of the extraparliamentary left, or what official discourse often refers to as the “extreme left,” as a critical security threat as well as criminalization of leftist dissent have been crucial for the establishment of prisons as an ongoing site of contestation, particularly since the advent of the cold war. This situation has been compounded by Turkey’s own checkered history, with periods of democratic politics and consecutive reversals in the form of coups d’état. As a result, since the 1970s, prisons have been catapulted to the symbolic forefront of political confrontation. At the end of the twentieth century, when the Turkish state was undergoing a transition from an authoritarian and tutelary to a more liberal-democratic regime, the situation of the country’s prisons came under increased scrutiny. Complemented by the high numbers of political prisoners and a consistently worrisome human rights record, the conditions of prisons were considered to be a direct reflection of the regime’s democratization. However, the ways in which the prisons were perceived and debated in the sphere of official politics revealed that more was at stake than merely the transition from authoritarian to democratic politics: prisons were symptomatic of a deeper issue regarding how the Turkish state imagined its sovereignty.

In this context the mass hunger strike conducted by political prisoners presented an acute and urgent political problem. To address this problem, the Turkish parliament convened for a special session to discuss the state of the country’s prisons. The debates that took place in parliament starkly portray how the elected representatives of the people across the political spectrum concurred in the view that prisons were in dire need of reform. Moreover, they reveal how the mass hunger strike in the prisons was perceived as a real political crisis that precipitated the need to reconsider the nature of the state’s sovereignty. This chapter presents the authoritarian state tradition in Turkey and its relationship to internal security threats, chronicles the emergence of prisons as site of political struggle with the state, and discusses how the “prisons problem,” increasingly a euphemism for the hunger strike, was interpreted as a “crisis of sovereignty” from the point of view of the agents at the helm of the state.

THE KEMALIST STATE TRADITION AND BIOPOLITICS

The state tradition in Turkey is marked by its strong capacity to shape and influence politics, both independently from forces in civil society and from governments, whether appointed or elected.1 This tradition, inherited from its imperial past, characterized by a high centralization of absolute power and the relative absence of civil society, has been critical in rendering the state a unique presence in the political sphere, if not the primary actor in politics.2

However, the authoritarian state tradition in Turkey is not only the legacy of its imperial past but also a rigorously reinvented practice of rule based on an assertive program of nation building and modernization in the early republican period. Having achieved national liberation in the aftermath of the First World War and abolished the monarchy, the republican forces in Ankara established their worldview and program of action as the ideological framework that would guide the bureaucratic and military elite who took charge of the state under the new regime. Since its adoption by the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Fırkası) in 1931 as the official program of the singleparty regime and incorporation into the Constitution six years later, Kemalism has largely defined the parameters of Turkish political culture, demarcated the field of political contestation, and constituted the central anchor of the regime up to this day.

As a positivist, modernizing ideology, Kemalism was the cement of the incipient nation-state. Through Kemalism, a new framework of legitimacy was constructed for the republic in which religious allegiance was replaced by national identity. Embodied in the figure of the charismatic leader-founder, Kemalism became the signifier of popular sovereignty and progress. It was characterized by an unrelenting project of national development, which found its most cogent expression in the goal of “attaining the level of contemporary civilizations.”3 The project of modernization, synonymous with Westernization, since “contemporary civilizations” were always the euphemism for Western powers, entailed the far-reaching transformation of society from above, through a combination of radical cultural reforms, social engineering, and economic development. Kemalism was an elitist republicanism combined with authoritarian pragmatism. These qualities, embedded within each principle of Kemalism, contributed to the construction of the hegemonic identity of the state, enabling its constitution as a unitary actor, relatively independent from society, and the construction of challenges to the state as internal security threats and therefore the objects of repression.

Kemalism was symbolized by the Six Arrows, each corresponding to a constituent principle: republicanism, nationalism, populism, étatism, secularism, and revolutionism/reformism. The principle of republicanism asserted that the idea of popular sovereignty is best embodied in the “republican” form of state. The republic was positioned against monarchy, substituting the National Assembly as the highest organ of legislation and administration in place of the sultanate, on the one hand, and against theocracy, substituting national identity in place of the religious ties of a community of believers (umma) as the basis of its legitimacy, on the other.4 Republicanism, at times used synonymously with democracy, depended not on the direct participation of the people in the government,5 but on the representation of the national will initially by the parliament, later by the single party and its leading cadres, and, finally, by Mustafa Kemal himself, as the founder and leader of the party and the state.6 The position of Mustafa Kemal as the “founding father” of the republic became entrenched in the paternalistic attitude of the republic toward the people who needed to become “mature” enough for self-government.7 The elitist and “tutelary” form of republicanism became solidified in the motto “for the people, despite the people,” while the substantiation of republicanism with democratic pluralism awaited the people’s political “maturation.”8 Meanwhile, until after World War II, the Republican People’s Party actively monopolized the political sphere: parliamentary opponents were eliminated, democratic experiments were short-lived, and popular insurrections were forcefully suppressed by the party-state.

The second of the Six Arrows, the nationalism principle, entailed a nonethnic and territorial definition of membership to the nation, based on the commonality of “language, culture, and ideal.” At the same time, it sought to promote peaceful international relations while preserving the unique character of Turkish society. Thus, as a principle, it was based upon a nonirredentist and psychocultural view of national identity as a substitute for religious ties in the establishment of unity within the territorial borders of the newly founded state. However, the increasingly abstract and homogeneous conceptualization of the unity of the nation and the active process of assimilation of various ethnic but Muslim minorities under the unifying identity of Turkishness paved the way for an ethnicist interpretation of nationality.9 That the idea of homogeneity in unity—an indivisible nation, an indivisible state, and, more significantly, an indivisible people—prevailed within Kemalist ideology is evinced by how allusions to “peoples of Turkey” were gradually replaced by those to the “Turkish people.”10

Populism, the third of the Six Arrows, claimed the absolute equality of the people in legal terms. But it also described the people of Turkey as a harmonious mass composed of different occupations rather than social classes.11 Thus, whereas the principle of populism endeavored to eliminate distinctions and privileges, on the one hand, it denied the existence of social classes, on the other.12 It reflected the ideal of a classless, organic society divided only along corporatist lines, one that functioned without conflict. By abolishing political inequalities, the state rendered class distinctions and social privileges nonpolitical, but it also preemptively foreclosed their repoliticization by asserting their nonexistence and, therefore, nonlegitimacy. The rejection of class-based politics lent justification for economic reforms that focused on rapid capitalization and the creation of a national bourgeoisie rather than on redistributive policies throughout the process of modernization and development.13

The fourth arrow, étatism, aimed to foster economic development as the prerequisite of national independence. While private enterprise was assigned the central role in the economy, étatism entailed large-scale state intervention; for example, setting up public economic enterprises, encouraging, protecting, and, if necessary, regulating private entrepreneurship, and establishing an amicable relation between capital and labor.14 While the ensuing mixed economy, accompanied by central planning, was largely a practical response to the urgency of development in the absence of initial capital accumulation, as well as to the post-1929 crisis context, it also strove to foster the development of a national capitalism.15 Kemalist étatism was ideologically positioned against both liberalism and socialism, with the contention of being a “Third Way” peculiar to Turkey.16 If the belief in the priority of rapid industrialization justified a top-down engineering of the economy in the eyes of the Kemalist elite, it also provided the state bureaucracy with more power, thereby reinforcing its authoritarian tendencies and autonomy vis-à-vis the rest of the social body.17

The fifth arrow, secularism, was one of the fundamental pillars of Kemalist ideology. Politically, the abolition of the caliphate in 1924 paved the way for the separation of affairs of the state from religion. Radical reforms such as the removal of Islam as state religion from the Constitution, the abolition of courts based on religious law (Sharia), the outlawing of religious orders, convents and schools, as well as Muslim dress and headgear, and the adoption of the Latin alphabet in place of Arabic script confirmed that secular reforms were not limited to politics but cast a wide social and cultural net. Identifying religion to be a matter of conscience and adopting modern science as the guiding principle of action, Kemalism asserted secularization as the indispensable precondition of progress and modernization.18 While the principle of secularism guarded the new government against unwelcome opposition from traditional centers of religious power, fortifying the national basis of its legitimacy, it also contributed to the making of the “new citizen,” one whose culture was devoid of religious obscurantism and rationally constituted according to principles of positivist thinking.19 Identity construction and social engineering went hand in hand: the invention of a glorious national history reaching back to pre-Islamic societies, such as the Hittites and the Sumerians, was coupled with the translation of the call to prayer (ezan) into Turkish, and the creation of a Directorate of Religious Affairs, under the office of the Prime Ministry, responsible for tasks from appointing religious personnel to overseeing the content of religious education. Such attempts revealed that secularism was intended to create a nationalized religion.20 Turkish secularization was primarily concerned with the decentering of popular religion and its substitution by a “civilized” and rationalized version of Sunni Islam under state control.21 It facilitated the promotion of a “renovated and turkified Islam that could help the state propagate new values.”22

The last arrow of Kemalist ideology, which can be translated both as revolutionism and as reformism, installed the principle of change within the heart of the ideology while it paradoxically formulated change as the protection of Kemalist achievements. The semantic ambivalence in the principle regarding radical change might have stemmed from the officially promoted efforts of language “purification,” by way of eliminating Arabic and Persian words from the language and substituting Turkish neologisms in their place,23 but the duality also reflected a deeper ambivalence regarding how Kemalists situated themselves and their actions with respect to the Ottoman past. Wanting to emphasize their revolutionary character, the Kemalist elite celebrated the radicalism of the new regime and its transformations while, at the same time, they were careful not to reject the past tout court but rather to maintain a tight control over the direction and substance of social change. Change was not foreclosed completely, in tandem with the goal of modernization, but was limited to progress within the framework of the new order, making sure that the new reforms themselves would not be subject to upending.24

Overall, the Six Arrows of Kemalism constituted a coherent worldview and a program of action whose goal was to transform the remains of the Ottoman Empire into a modern, independent nation-state. Because of its role as a constituent ideology, animating the self-understanding of the founding cadres and the retrospective narration of the struggle for the founding,25 Kemalism drew its strength from its ability to create a new state that would endure. This achievement became, in turn, the evidence of the validity and legitimacy of Kemalism as its founding ideology. The ability of the ruling elite of the republic to utilize Kemalism as a political resource, combining the coercive authority derived from their position of power with the persuasive force of the constituent ideology, to garner the consent of different sectors of society and provide them with a national-popular program, and political, moral, and ideological leadership, transformed Kemalism into the hegemonic ideology of Turkey.26

The hegemony of Kemalism, which buttressed the strong state tradition in the new republic and affirmed its relative autonomy vis-à-vis the social sphere, also endowed it with a unique opportunity not only to modify, shape, and control society, according to the outlines of the republican program, but also to improve its well-being, foster its growth and strengthening, and increase its productive forces and quality of life, according to the program of modernization. The social engineering responsible for in the making of the “new citizen” involved, alongside the social and cultural reforms that put into effect the directives of the Six Arrows, the deployment of a whole range of biopolitical techniques by which a healthy, productive, and docile population was to be produced out of the ruins of a collapsed empire whose diverse peoples had been devastated, dislocated, and decimated by incessant warfare, heavy taxation, poverty, disease, and malnourishment. Kemalist cadres predicated the health of the new body politic upon the health of the citizen’s body and vice versa. To this effect, they resorted to techniques of population management that had been introduced in the late Ottoman period, especially in the second half of the nineteenth century, but deployed them with greater rigor and intensity.27

In order to achieve the desired improvement of the population as part of the modernization program, the Kemalist state intervened, with varying degrees of success, in the spheres of individual and public health, tackling a range of issues such as high rates of child mortality, high rates of morbidity due to preventable diseases and epidemics, widespread alcohol use and venereal disease, and low rates of reproduction, among others. Through a series of measures, not all of which were systematic, via the formal education system as well as semi-independent institutions (such as hospitals and clinics, voluntary sports organizations, local party branches, and newspapers), the state attempted to educate citizens on how to achieve personal hygiene, conducted large scale vaccinations, instituted preventive health care, encouraged reproductive health and higher birth rates, fought prostitution and alcohol, and paid special attention to the development of physical education and sports.28

While this modernist deployment of biopolitics upon the social sphere was largely contemporaneous with similar techniques utilized in the West (and especially took inspiration from Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany’s achievements in educating and improving the well-being of their people under similarly dire circumstances of postwar reconstruction), it was comparatively mild in its racism. Scholarship shows that a racialized discourse did become an important component of the biopolitics of the Turkish party-state, especially in the 1930s, in an effort to prove to the West that the Turks were “white” and not of an inferior race, and that they, too, had an “innate ability to modernize.”29 This period also corresponds to a more ethnic definition of Turkishness and the racialized overtones in the identity construction of the Kurds and the non-Muslim populations within Turkey. Although there was a lively discussion regarding the benefits of eugenics in the early republican period, the actual policies of the state remained at the level of positive encouragement of reproduction rather than forced sterilization (however, the prohibition of marriage for the disabled in the early republican period should also be noted).30

Nonetheless, it would be inaccurate to assert that racism became the primary mechanism for combining the sovereignty of the Turkish state with the development of biopolitics during this period. Biopolitics in the early republic remained largely instrumental for the state and relatively extraneous to it; it was deployed, but without a real internalization of its techniques as state logic. These techniques were part of a “civilizing” mission in which the creation of a strong nation was understood to depend on the fostering of a healthy population that would constitute a productive workforce, with a greater readiness for national defense and dynamic growth potential. The identification of the healthy body politic with national unity, however, did lead to the construction of dissent as a “foreign” and “subversive” element that endangered the republic. In the realm of official ideology, radical political opposition to Kemalist principles was interpreted as a dangerous force that weakened the nation and should be expunged, like a healthy body expunges disease.

While the presence of an official ideology is always in contradiction with democracy, the situation in Turkey was complicated by the fact that it was within the framework of official ideology that democracy was eventually introduced. This development further contributed to the strong presence of the state as a political actor, despite the eventual enlargement of the democratic field of contestation.31 In fact, it set strong limitations on what could count as legitimate political contestation and created an enduring bifurcation between the state and politics, the former not only as an active agent in the latter but also as the underpinning guarantor that continuously inspects it, controls its development, and keeps it within assigned limits defined by Kemalism.

In this context, the Democrat Party (Demokrat Parti), against which the Republican People’s Party (CHP) experienced a dismal defeat in Turkey’s first free elections in 1950, did not significantly diverge from Kemalism. Rather, DP accepted, utilized, and further reproduced Kemalism, albeit with a more liberal economic interpretation of the étatism principle, relaxing some of the controversial reforms of secularism (reverting to the recitation of the ezan in Arabic, for example), and adopting a more pro-Western stance in international politics. In distinction from the early republican period’s biopolitics directed at the health, education, and fertility of the population, the interventions of the state on the social body during the democratic period, beginning in the 1950s, took on the additional dimension of targeting social welfare and aid, particularly in order to alleviate the growing disparities of income and assuage social conflict.32 Despite broad continuities with the ideological orientation of the single-party period, DP’s increasing authoritarianism and aggressive pursuit of economic and social aggrandizement for its populist base through a dense network of patronage relations paved the way for its ousting from power by the 1960 coup d’état.33

Given the strong state tradition and its relation to the field of politics, it is not surprising to find that the 1960 coup, as well as the subsequent military reversals in 1971, 1980, and 1997, have all been carried out as interventions into politics so that in these “states of exception” deviations from original Kemalist principles at the hands of political parties could be corrected and the country put back on the “right course.”34 Acting as a bulwark against the “deformation” of the constituent principles of the regime, the military thereby strengthened the unitary agency of the central state apparatus vis-à-vis successive governments, which were tolerated only insofar as they were able to include, appropriate, and internalize Kemalist principles, and, once again, enshrined Kemalism’s position as the “only” official ideology of the republic in the 1982 Constitution.

The hegemonic status of Kemalism, its propagation through the state apparatuses, both repressive and ideological, and its recurrent reinforcement by the military, has had important consequences for Turkish politics. Not only has it granted a privileged role to actors who are part of the state bureaucracy, by virtue of a relative autonomy from political and social forces and a strong and unified capacity to influence the direction of politics, but it has also enabled the state to carry out the Kemalist program of top-down modernization, relying on disciplinary and biopolitical techniques. Elected governments have largely accepted and reproduced this autonomy and have been deeply invested in guarding the state’s hard-won sovereignty and unitary identity, as well as its achievements in social, economic, and cultural transformation. As a result, rival ideologies and their proponents have been constructed as “enemies” and “foreign bodies” that threatened the health of the body politic.35 This orientation has led to the privileging of raison d’état over political contestation, while it has also facilitated the entrenchment of an authoritarian attitude toward dissent, one that has remained operative even during periods of democratic government. As a result, the state has treated the politicization of differences of ethnicity, class, religion, and language with great suspicion. With little room for opposition, especially in radical form, the constricted political space in the republic has largely been occupied by the state as one of the main political actors of Turkish politics.

THE CRIMINALIZATION OF THE LEFT

Nevertheless, the foundational principles of Kemalism have met radical opposition from different quarters: Islamists, Kurdish nationalists, and leftists have each presented different challenges to the principles of secularism, nationalism, and populism, as well as to the homogeneous unity of the nation-state envisioned by the ruling elite. Oppositional currents emerging from these quarters have almost always been regarded as “divisive currents,” with their roots outside the country as an indication of their “foreignness” and subversiveness to the project of national unity and sovereignty entailed by Kemalism. As such, they have been considered instruments of foreign powers that plant and nurture the seeds of domestic contention to weaken, destabilize, and ultimately divide the country in their own interests.36 Classifying these oppositional currents as “internal threats,” the state has viewed them with suspicion and hostility, pointing to their invisible or potential ties to external enemies and regarding them as insidious, debilitating, dangerous, and perhaps even more recalcitrant against attempts at elimination than their external counterparts. As a result, the state has put much effort in devising strategies to confront and neutralize these threats to its security, with serious legal repercussions for their proponents.37

The political left has particularly borne the brunt of Kemalist authoritarianism from the very inception of the republican regime. Although the nationalist cadres of the nascent Turkish state were able to establish amicable and beneficial relations with the young Soviet Union while navigating the tensions between the powers occupying the remains of the Ottoman state, these ties slowly withered away after Turkey’s declaration of independence. Communist forces active in the country were suppressed and eliminated by nationalist cadres during the years of the War of Independence (1919–22) and the early republic.38

Despite this rocky beginning, the leftist opposition in Turkey followed the Communist International in its support of the Kemalist struggle for national independence as a progressive element in the international fight against imperialism and an example to other oppressed nations in the East during the initial period of the republic. At the same time, the Kemalist reforms against theocracy and monarchy, on one hand, and strides against semi-feudal structures, on the other, were welcomed as the “bourgeois democratic revolution” that would facilitate the development of the working class and set the stage for a future proletarian revolution. However, because of their “bourgeois” character, the leftists expected that there would be objective limits to how far Kemalist reforms could extend. Land reform, for example, stood at the boundary of how radically Kemalists would be willing to transform social relations, in their view. Those on the left were quick to predict that Kemalists would not risk distributing land to poor peasantry since it would undermine their alliance with the landowners. And they were accurate in their prediction.

As a result, the left occupied an awkward position from which it had to build a precarious combination of support and opposition to the Kemalist regime.39 Especially during the Second World War, after the decentralization decision taken by the Communist International in 1939, leftist opposition was largely settled on the strategy of advancing the “national front” against fascism and imperialism in compliance with the urgency of the international situation and promoting a noncapitalist path of development where possible.40 This meant that the left accepted an increasingly muted role with respect to Kemalist cadres politically and allied itself with Kemalism ideologically, except for launching criticism against wartime policies that encouraged profiteering and calling for democratic elections.41 The interpretation of the Kemalist revolution as the first bourgeois democratic step in liberation within a linear and stagist construction of history strengthened this alliance, as it was expected that this crucial phase would enable the development of a national capitalism and a national proletariat, which could then be organized for the next socialist stage. The Kemalists and the leftists therefore shared the desire to attain full national independence and commonly emphasized developmentalism. The low profile of the left was also a consequence of difficulties organizing, as the communists were often the first to be adversely affected by the repressive practices of the center.

After the transition to democracy in 1946, leftist opposition had a brief period of legal freedom, both under the auspices of the Democrat Party and as small but short-lived independent parties. However, the optimism generated by the sweeping victory of DP, which broke the political monopoly of the Republican People’s Party and dislodged it from power, did not last long. Leftist opposition was soon disillusioned with the DP government in the face of its similarly authoritarian tendencies, visibly pro-Western posture, populist concessions in religion, networks of patronage, rapid program of industrialization without concern for growing disparities, and its welcoming of the support of foreign capital.42 The left largely interpreted the changes brought about by the Democrats as a retreat from the progressive aspects of the Kemalist regime, such as nationalism, étatism, and secularism. The McCarthy-like anticommunist attitude of the new government, soon actively closing down leftist parties and instigating waves of persecution directed at intellectuals and militants, added material force to this disillusionment.

In this light, the leftists welcomed the military coup of 1960 as a restoration of the Kemalist order against the excesses of democracy through the intervention of the progressive forces of the state.43 Carried out by colonels instead of the High Command, the coup of May 27, 1960, enlisted the support of CHP and based its legitimacy on a coalition of republican politicians, bureaucrats, civil servants, students, and leftist intellectuals, all of whom came together around the goal of completing the unfinished Kemalist revolution. The new regime indicted the Democrat Party government for having created a “tyranny of the majority” and put its leading political figures on trial. Prime Minister Adnan Menderes and two ministers of his cabinet were convicted of treason and hanged.

After the adoption of the more libertarian and democratic 1961 Constitution, the Turkish political scene witnessed an unprecedented spread of communist, socialist, and social-democratic ideas and the formation of several dozens of groups and organizations that together constituted an extraparliamentary leftist opposition. This growth was soon translated into parliamentary representation. In 1965 the Workers’ Party of Turkey (TİP) won fifteen seats.44 In the meantime, the growing popularity of the left drifted the Republican People’s Party, the heir of the single-party state, leftward. The new leadership of Bülent Ecevit signified the left-of-center stance.

In stark contrast to the elitist “monoparty” period,45 the rising demands for social justice and welfare on the streets evidenced a dramatic change in the dynamics of Turkish politics, forged through political pluralization, economic development, industrialization, urbanization, and rising social inequalities. The general strike of June 15–16, 1970, demonstrated the mounting strength of the left, despite persistent attempts at repression.46 A strong indication of the increased politicization of the masses and the expanding influence of leftist ideas was the establishment of the Confederation of Revolutionary Trade Unions (DİSK), with which trade union membership rose from 250 thousand to around 2 million. However, the emergence of the trade union movement, activism among university students, labor strikes, and other social struggles also accentuated the hostility of the state toward the left.

The March 12, 1971 intervention of the High Command was effected through a memorandum, which installed a group of technocrats in power without suspending the parliament. The new cabinet under Nihat Erim was accompanied by constitutional amendments restricting rights and liberties (of the 157 articles of the 1960 Constitution, 57 were amended). The hanging of three popular leftist student leaders—Deniz Gezmiş, Yusuf Aslan, and Hüseyin İnan—in 1972 exemplified the politics of the 1971 coup, especially in contrast to the 1960 coup in which the three political figures who were hanged were the top three officials of the DP government. If the state’s earlier corrective was against authoritarian populism, this time it was against left-wing politics from below. This intervention also signaled the intensification of the left’s further criminalization.

The 1970s were a period of growing political polarization between the left and the right that was quickly translated into extremely sectarian politics and escalating violence, which rendered civil war a plausible threat. The parliament was at a political stalemate due to unstable coalition governments and feuding between the two major parties: the left-of-center Republican People’s Party under Bülent Ecevit’s leadership and the right-of-center Justice Party (Adalet Partisi) under Süleyman Demirel’s leadership, which continued the line of the Democrat Party suppressed by the 1960 coup d’état. The oil crises and the embargo following the Cyprus invasion of 1974 hampered the economy and isolated Turkey in the international sphere. The two Nationalist Front (Milliyetçi Cephe) coalitions and the following minority cabinet of the Justice Party allowed right-wing parties, the Nationalist Action Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi) led by Alparslan Türkeş and the National Salvation Party (Milli Selamet Partisi) led by Necmettin Erbakan, to play a disproportionately powerful role in relation to the number of seats they commanded in parliament. While the incorporation of ultranationalist and Islamist currents into government further polarized the political sphere, the internal politicking between coalition members brought the parliament to an impasse.

The ineffectiveness of the parliament to address the country’s deepening economic crisis and social problems pushed politics to the streets in a rising tide of violence that claimed many lives. Right before the 1980 coup, an average of fifteen to twenty individuals were killed on a daily basis in street vendettas between right-wing “commandos” unofficially linked to the National Action Party and left-wing “revolutionaries” linked to numerous splinter organizations and factions on the extraparliamentary left, a number of which had grown out of the youth organizations of the Workers’ Party (TİP) and taken increasingly radical, vanguardist directions. These forces divided urban neighborhoods according to opposing ideological orientations and spheres of influence. At the same time, leftist factions were highly conflicted among themselves and capable neither of unified action nor of decisive social mobilization.47 During the same period, the general militarization of daily life was compounded by numerous assassinations of intellectuals, journalists, and politicians, whose perpetrators remained largely unknown. Bloody May Day in 1977 left 36 dead (5 of whom were shot by unknown snipers, the rest crushed in the stampede) and 130 wounded. Increasing extremist violence in the streets went hand in hand with rising sectarian tensions between Sunnis and Alevis.48 The ongoing organized assaults on Alevi communities, in the form of raids on coffeehouses, homes, and shops, reached a peak with the massacre in the southeastern province of Kahramanmaraş in December 1978. This attack alone took the lives of more than 100 people.

One of the most important aims declared for the military coup d’état of 1980 was, in the words of the High Command, to put an end to the “terror” and “anarchy” caused by the threat of communism on the streets and to bring order to a country that not only lacked proper government by the civilian parliament but also had become unruly and “ungovernable.” The state was, once again, intervening in politics to curb the contestation and violence among extremes, impose constraints upon political actors and civil society, end radical social mobilization, and correct the deviation of the country from Kemalist principles. The project of eliminating internal threats to security was soon transformed into political engineering and refounding when the military not only declared a “state of exception,” in which all political opposition was brutally suppressed, but also dissolved the 1960 Constitution (already constricted by the amendments of 1971) and set up a new constitutional order.

As soon as the military took over, it shut down the parliament and banned all political parties, expropriating their assets and prohibiting party leaders from political activity. The military also embarked on a campaign against civil society, disbanding all associations and trade unions, including DİSK, still the largest workers’ organization at the time.49 According to the statistics compiled by human rights organizations, a total of 23,677 organizations were banned by military rule. Major newspapers and journals were banned, some of them permanently, along with hundreds of films. The Kurdish language was made illegal. Classes on religion became a compulsory part of primary and secondary education. A Council of Higher Education (Yüksek Öğretim Kurulu) was set up in Ankara, putting an end to university autonomy. During the coup, some 30,000 people were fired, forced to resign, asked to retire from their jobs, or exiled to remote posts in the rural provinces. Those who were forced to resign include 3,854 teachers and 120 university professors. Another 30,000 people sought political asylum in European countries; 14,000 individuals lost their citizenship; 388,000 individuals could no longer hold a passport and were, in effect, imprisoned within the country. Over 300 people simply disappeared; another 300 died in prisons.50

The criminalization of dissent reached unprecedented numbers in the history of the republic. In three years 650,000 people were arrested, 230,000 were prosecuted, and some 65,000 were convicted. The number of arrests comprised about 2.6 percent of the adult population, although unofficial estimates are twice this figure.51 Nearly of half of those who were prosecuted (98,404 individuals) were charged with membership in illegal organizations. A third of those who were prosecuted (71,000 individuals) were charged with crimes defined by three infamous articles of the Penal Code: 141, 142, and 163. These articles stipulated significant limitations on the right to organize (141) and freedom of expression (142 and 163), rendering even nonviolent propaganda punishable. A symbolic climax was the prosecution of approximately 7,000 individuals with the death penalty, even though capital punishment had not been carried out in Turkey since 1973. Of the 517 individuals eventually condemned to death, 50 were executed.52 The first two of these executions occurred only a month after the military assumed power. One from the “extreme” right and another from the “extreme” left, these executions were singled out to represent the alleged “even-handedness” of the new regime against both radical ends of the political spectrum.

Despite its rhetorical neutrality and ostensible equidistance to both extremes of the political spectrum, the conservative sympathies of the military inevitably colored the legal, political, and economic order that the military sought to put into place. On the economic front, the military installed the IMF-prescribed economic stabilization program introduced in January 1980 (which included a devaluation of the currency by one-third of its value) and facilitated the emergence of an open and competitive market economy oriented toward growth by exports and flexible currency exchange rates, moving away from the previously heavily state-regulated economy based on import substitution and fixed exchange rates.53 Politically, it put into place new limits on contestation. The new electoral law introduced a 10 percent national threshold, which intended to preclude small or regional parties from gaining representation in parliament and leverage beyond their actual popular support, while it also encouraged a two-party system gravitating around centrist parties. The Constitutional Court was assigned the responsibility and power to close down political parties considered to represent ideological extremes, whether from an ethnic, a religious, or a class perspective.54 Legally, the 1982 Constitution, adopted by a national referendum under military rule,55 introduced many loopholes through which fundamental rights and liberties (especially the right to strike and the right to free assembly) could be restricted.56 Meanwhile, the new Constitution guaranteed a prominent role for the National Security Council, composed in part of ministers of the government and in part of the High Command, as an advisory board to the government. If the decision on the “exception” reveals the real locus of sovereignty, the 1980 coup, through which the military usurped this power permanently, not only confirmed the military’s constituent role but also integrated it into the civilian order as a limiting force upon elected governments through the stipulations of the 1982 Constitution.57

The first elections took place in November 1983 under the auspices of military rule in order to transfer government to civilian hands. However, the return to normalcy from the military coup came gradually, in subsequent waves of democratization.58 Martial law was fully in effect until March 1984 and was only gradually phased out in July 1987. In its place, a regional “state of emergency” was put into effect (in the eastern and southeastern provinces where the Kurdish population is concentrated), with extraordinary provisions for the governing officials to override constitutional rights and liberties if and when necessary. The state of emergency was also gradually phased out throughout the 1990s and lifted completely only at the end of 2002, upon two decades of low-intensity warfare with the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan (PKK) that undergirded the long transition to civilian rule.59

During the protracted process of civilianization, oppositional political currents, which were deemed to be targeting the “constitutional order of the state, the indivisible unity of the country, and the welfare of the nation,”60 continued to be considered pernicious, centrifugal forces whose suppression by legal and illegal means was considered legitimate. Torture, despite the process of democratization and the ratification of the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and the United Nations Convention Against Torture in 1988, remained rampant, especially under police custody, and, according to the United Nations Committee Against Torture, “systematic.”61 Even though the armed struggle of the Kurdish separatists led by PKK soon surpassed leftists as the highest priority on the list of strategic security concerns defined by the National Security Council, the extraparliamentary left continued to retain its role as an “internal threat” to security and order, especially as it became more militant and violent in the early 1990s. Despite the collapse of the Soviet Union that led to the waning of radical-revolutionary leftist politics around the world, the extraparliamentary left in Turkey gained a new momentum with the armed struggle of the Kurdish nationalist movement, rapid social and economic transformation, and the culture of collective resistance in prisons. Meanwhile, the large flows of migration from the countryside into the cities nourished all radical movements – leftist, Islamist, and ethno-nationalist, which competed for this constituency.62

In response, the hostile relationship of the Turkish state with its radical challengers took an important turn with the promulgation of the Law for the Struggle Against Terror in 1991.63 The antiterror law not only folded the state’s “internal threats” into the category of “terror,” adopting discourses and practices of securitization and preempting the global turn to antiterrorism legislation by a decade, but it also dictated policies and procedures that would ensure the distinctive treatment of “terrorists” vis-à-vis other populations who infringed the laws. This law donned the state with the ability to pursue its vigilant persecution of dissidents and oppositional forces with impunity and with remarkable continuity, now through democratic rule under successive governments, despite their ostensible ideological differences. The antiterror law also marks an important turning point in the history of biopolitics in Turkey, precisely because it signals that the hitherto predominantly extraneous and instrumental deployment of governmental techniques by the state in order to foster the health and well-being of the population in line with the program of modernization is now being supplanted by a rethinking and reorganization of the state apparatuses and their practices around questions of security—the redefinition, classification, regulation, and management of threats as an integral part of the health and well-being of the population. From now on, biopolitical techniques are no longer simple tools to be imposed upon the social sphere, but become part and parcel of the construction of sovereign power itself, manifest most clearly in the exercise of its right to maintain public order and to punish those who attempt to subvert it, selectively and with respect to security objectives, biopolitically defined. Here, we have an infusion of biopolitics into the very tissue of sovereign power. The process of securitization precipitated by the antiterror law in the spheres of policing and imprisonment technologies refers to an integration of sovereignty and biopolitics and their mutual penetration at an unprecedented level.

The antiterror law thereby provided the conditions of possibility for the intensification of the state’s pursuit and containment of its challengers: Kurdish separatists, radical leftists, and political Islamists. Torture remained a widespread and systematic practice.64 The hawkish approach to the Kurdish question, exacerbated by armed conflict with PKK in the southeast, was complemented by extensive profiling, wiretapping, and other means of covert domestic surveillance as well as by security operations in urban centers against Kurdish and leftist opposition and the forcible suppression of erratic insurrections in the shantytown neighborhoods and other spontaneous riots. However, the vigilance displayed by civilian governments did not prevent the military intervention of February 28, 1997, fourth of its kind in the republic’s history. This “soft” or “postmodern” coup,65 as observers have called it, came at a juncture of intensified social conflict and the growing rise of political Islam.66 It did not suspend civilian rule, but only reprimanded the government with a harsh statement warning against religious extremism. The coalition government of Tansu Çiller’s True Path Party (Doğru Yol Partisi) and Necmettin Erbakan’s Welfare Party (Refah Partisi) was eventually pressed to resign, reaffirming the military’s role as the “guardian” of national sovereignty and its core republican principles. The hegemony of Kemalism was thereby reasserted, without significant discontinuity in the repressive attitude of the state toward its challengers. It was only as the military gained control over the Kurdish insurgents, under the added pressure of a long-desired European Union membership, that successive constitutional reform and democratization packages were allowed to pass in parliament, now dominated by the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi) under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. AKP’s strong popular support enabled the government to facilitate the process of democratic reform in order to consolidate the precarious transition from the bureaucratic-authoritarian and tutelary regime to civilian democracy, a process that, despite its contradictions, continues to this day.67

PRISONS AS SITES OF CONFRONTATION AND THE ANTITERROR LAW

In the post-1980 context, the measures that sought to eliminate internal threats to security, whether by military intervention and the forceful repression of radical opposition or the criminalization of opposition through the punitive policies of successive democratic governments, produced momentous consequences for the country’s prisons. Two of these consequences stand out among others: first, the informal but consistent partition of prisons, with corresponding rules and regulations, according to prisoner status and, second, the entrenchment of prisons as a symbolic site. By the mid-1990s, prisons in Turkey, especially the wards in which political prisoners were confined, had become sites of a highly politicized confrontation between the state and the insurgents. Prisons were transformed into a direct and transparent interface between the state and its unruly “crowd.”68

In the first half of the 1980s the military regime’s punitive practices were exceptionally harsh, in keeping with its ideological commitment to eliminate political extremes. As a result, those who were affiliated with radical politics, left and right, were subjected to the grinding mill of the military prison. Moreover, those detained for “political” reasons were treated very differently from prisoners held for “ordinary” crimes, although this distinction in status was not yet codified into the law. In fact, one of the first moves of the military was to impose upon political prisoners the status of “arrested personnel,” a status beneath the lowest private in the chain of command, according to the military’s criminal procedural code of regulations called 13/1. The task of the prison commanders was to make the “arrested personnel” accept and respect the military chain of command and discipline, through a variety of measures, including making prisoners salute all military personnel (including privates) as “commander,” coercing them to walk and talk like soldiers, sing military marches, repeat the national anthem and Atatürk’s famous “Speech to the Youth” by heart, recite prayers at meals, and wear prison uniforms. In cases of disobedience to the inculcation of a militarized dispoliticization and Turkification, violence was rampantly applied.

The internal partitioning of prisons between those held for “political” crimes and “ordinary” crimes was therefore largely an effect of the differential treatment of prisoners by the military administration on a day-to-day basis, ranging from simple disciplinary measures to physical violence used to make them submit. It was not that violence was lacking in the interactions of the military command with “ordinary” prisoners. Violence was widespread. However, the violence directed at “political” prisoners was of a different caliber, both in its arbitrariness and brutality and in its specific design to eliminate dissident identities and political affiliations.

The fierce experience of the military prison led to the emergence of individual and collective resistances in prisons, initially against the ongoing practices of torture and degrading treatment and, in successive stages, over access to health care, lawyers, visitors, and the regulation of daily life in prison. Although the brutality of prison life somewhat subsided with the transition to civilian rule in 1983, prison struggles increased in rigor. As we will see in detail in the next chapter, a whole range of issues revolving around life in prison soon became politicized, ranging from what prisoners could read, eat, wear, and keep as personal belongings, to how often they could receive family visits, legal consultation, and medical care. Tactics of prison struggles varied: sometimes prisoners only shouted slogans, banged on bars, resisted body counts and ward searches, boycotted court hearings and visits; other times they organized uprisings, carried out violent occupations (of wards, yards, and main hallways), and took prison guards hostage; occasionally, they also resorted to hunger strikes of various durations, acts of self-immolation, protest self-hangings, and death fasts. These acts of resistance achieved mixed results, but collectively they functioned to reinforce the internal partitioning of the prisons among “ordinary” and “political” prisoners. In the 1990s, especially in the aftermath of the promulgation of the antiterror law, the crackdown on the radical left in urban centers and the intensification of low-intensity warfare against Kurdish separatism in the east continued to fill prisons with younger generations of militants. As political prisoners increased in numbers, prison struggles became more confrontational. The prison assumed the status of an independent site of hostile political engagement between the state and those it considered to be “internal threats.”

By the late 1990s the ongoing struggles of political prisoners in many prisons across the country had produced a complex and internally differentiated penal sphere based on a myriad of arrangements, partitions, and selective practices, formal and informal, regular and ad hoc, that regulated prison life in a way that acknowledged, at least de facto, differential rights and privileges accorded to political prisoners in comparison to other prisoners held for “ordinary” crimes. The legal ambiguities and discontinuities created by different and, at times, inconsistent executive decrees issued by various governments to govern the prisons and address their problems, coupled with practical measures taken by prison administrations and their concessions to the political prisoners in their attempt to assuage the ongoing unrest, led to the emergence of a certain autonomy of the wards of political prisoners from the administrative procedures and practices that regulated the lives of the rest of the prison population. Accordingly, even though political prisoners had to answer to body counts and were subjected to random searches and seizures conducted by the prison administrations, even though they nominally had to follow the general rules of conduct applicable to conditions of imprisonment, they were otherwise permitted to organize their daily lives themselves, without much interference from the prison administrations. Over time, the wards of political prisoners were transformed into self-governing enclaves, whose existence eased the burden of prison administrators in regulating daily life in the prison and ensured the maintenance of order and peace within large groups of politicized individuals, on the one hand, while, at the same time, it increased the frequency of collective mobilization and unrest, and, as a result, the anxiety and troubles of prison administrators and state officials, on the other hand. The experience of collective life in the prison wards reinforced the prisons as sites of confrontation with the state while, at the same time, they became a venue of generating political leadership for the radical left, both inside and outside prisons.

If the rapid growth in the numbers of political prisoners was one factor contributing to the radicalization of prison struggles and the strengthened autonomy of prison wards, the other factor was undoubtedly the impact of the antiterror law. The stipulations of the antiterror law affirmed the distinct status of political prisoners vis-à-vis other prisoners, even if it did so at the expense of bringing political prisoners within the fold of an expansive discourse of terrorism and its attendant practices of securitization. The antiterror law contained a stipulation for the conditional release of prisoners for crimes committed until 1991 (Provisional Article 1), by which those who had been given the death penalty would be released after ten years, life imprisonment would be commuted to eight years, and all other sentences would be commuted to one-fifth of their term. With this article, most prisoners incarcerated since the 1980 military coup would be released. The antiterror law therefore established a break between the preceding military coup and the democratic regime, instituting new forms of criminalization instead.

Several controversial aspects of the antiterror law are worth highlighting because they have had important repercussions for delineating the vicissitudes of oppositional forces in their interaction with the state and their specific form of criminalization in the 1990s under the aegis of a democratic regime. The most prominent characteristic of the law was its scope, determined by the rather loose and broad definition of terrorism. According to Article 1 of this law, terrorism was defined as

any kind of act done by one or more persons belonging to an organization with the aim of changing the characteristics of the Republic as specified in the Constitution, its political, legal, social, secular and economic system, damaging the indivisible unity of the State with its territory and nation, endangering the existence of the Turkish State and Republic, weakening or destroying or seizing the authority of the State, eliminating fundamental rights and freedoms, or damaging the internal and external security of the State, public order or general health by means of pressure, force and violence, terror, intimidation, oppression or threat.69

Written in such a way as to encompass opposition to the state from a wide spectrum of positions (whether based on ethnicity, religious affiliation, or class politics), the law included not only “force and violence” but also manifold forms of “pressure,” “intimidation,” and “threat” to the unity of the state, its constitution, internal and external security, public order, and health within the scope of terrorism. Article 2 further broadened the universe of “terror” crimes by defining not only those who committed crimes to attain the goals stated in Article 1, but also those who were members of organizations aspiring after these goals (regardless of whether they had committed such crimes themselves) as “terrorist” offenders. Meanwhile, the criteria for establishing membership in “terrorist” organizations were left largely ambiguous. The law’s infamous Article 8 prohibited not only demonstrations and marches but also written or oral propaganda, “regardless of the methods, intentions, and ideas behind such activities,” thereby greatly restricting the freedom of expression.70 In the name of the “struggle against terror,” the law extended protection to antiterrorism police, shielding them from prosecution with the protective provisions specified for civil servants and, in case of prosecution, waiving remand and assuring financial support for their legal expenses out of resources allocated to the Ministry of Justice. The law therefore not only left room for torture and maltreatment of detainees but also sanctioned state-sponsored violence by lending protections to the perpetrators of such violence.

Because the antiterror law created a two-tier criminal justice system, one for “ordinary” offenses and the other for “terror” crimes, it wedged the respective prisoner populations further apart, situating them in considerably different conditions at four separate stages in the system: (1) detainment and arrest, (2) trial (with or without remand), (3) sentencing, and (4) execution of sentence. As such, even though the state did not officially recognize a separate class of prisoners with political status, it indirectly fixed their status (and hence, treatment) as different from ordinary offenders once they were captured by the state apparatus.

Accordingly, those detained as suspects for “terror” offenses would be subject to exemptions from the stipulations of the Criminal Procedural Code (Law No. 3842) otherwise instated to protect the rights of detainees and organize legal procedures for detention and trial. While detainees suspected of “ordinary” crimes could benefit from legal counsel immediately, those detained as suspects for “terror” crimes did not have to be reminded of their rights as part of due process.71 Furthermore, they could be held in incommunicado detention for forty-eight hours and, if the crime was collectively committed, up to fifteen days (this amount went up to thirty days if the crime was committed in a region where the “state of emergency” was still in effect).72 Such practices legalized a whole set of infractions upon fundamental rights, while they created a significant time frame for arbitrary detention. They put the suspects of “terror” crimes at the mercy of security forces and provided ample opportunities, if not incentives, for the use of torture under detention.

The situation was no better at the stage of trial. The antiterror law assigned jurisdiction over “terror” cases to the State Security Courts (DGM), special courts of law equipped with increased discretionary powers. For “terror” crimes, trials would generally proceed with remand, jump-starting imprisonment much before the trial’s end was in sight (and, most frequently, trials went on for several years before they could be concluded). At the sentencing stage, Article 5 of the antiterror law allowed the discretionary increase of the sentences of crimes committed with a “terrorist intent” by half and prevented their commutation into lesser forms of punishment (such as fines). The conditional release of “terrorist” offenders was also tied to more stringent criteria: the earliest that those convicted of “terror” crimes could be discharged was upon the completion of three-fourths of their sentences, while this period was set at two-fifths of sentences for “ordinary” crimes.

While these stipulations of the antiterror law already determined two very distinct paths in the criminal justice system, another provision (Article 16) was that the sentences for “terror” crimes should be executed in “special” penal institutions in which convicts and detainees would be barred from having open visitation or communicating with other prisoners. This article thereby introduced the model of the high security prison as the proper site of punishment for “terrorists.” Although there had been several attempts by various governments throughout the 1990s to open high security prisons in accordance with the antiterror law, these efforts had been suspended, having encountered serious prisoner resistance and public controversy. The threat of the full implementation of Article 16 by way of introducing cellular confinement either in new penal institutions or by the piecemeal renovation of existing prisons loomed large in the second half of the 1990s. This threat led to the escalation of organized resistance on part of political prisoners, who were the first constituency destined for cellular confinement. While the mass hunger strike in 1996 (which ended with 12 casualties) led to the temporary abandonment of the high security prison thanks to the reconciliatory moves of the government, the mass hunger strike launched in October 2000, this time with greater participation, precipitated a full-blown crisis for those at the helm of the state. The death fast struggle catapulted the prisons not only to public view but also to top priority on the government’s agenda.

THE OFFICIAL DIAGNOSIS OF THE PRISONS PROBLEM

In the eyes of state officials, prisons were a continually bleeding, nonhealing sore. They were dysfunctional, ineffective, and embarrassing. Instead of being sites of discipline and order under the tight control of the state, they had become places of disobedience and disorder. Instead of venues for punishment, they had turned into the breeding ground of crime. Instead of rehabilitating criminals and transforming them into law-abiding citizens, they tended to produce more experienced and audacious criminals. Instead of curbing terrorism, they had become “command centers” for further terrorist activity.73 They were, in short, institutions in dire need of reform. Mainstream newspapers covering the “prisons problem” had already carried the state’s perspective to their headlines, which proclaimed: the “Confession of the State: Terrorists in Charge of Prisons.”74 Newspapers referred to prisons as “factories of crime.”75 Beyond this sensationalism, however, stood a real problem, acknowledged not only by the state but also by forces in civil society. At this point, institutions such as the Union of Bar Associations (Türkiye Barolar Birliği) and the Istanbul Bar had already been solemnly convening working groups, organizing conferences, and writing reports in order to delineate the problems in the criminal justice system, discuss possible solutions, and inform the public.76

For the state, prisons were simply disastrous for public relations. On the one hand, there was the notorious reputation of prisons inherited from the legacy of the military coup d’état, a reputation that reinforced Turkey’s compromised human rights record and put the Turkish state in a difficult position vis-à-vis the West, especially the European Union. On the other hand, and what prevented Turkey from writing off this reputation as an artifact of the authoritarian past, was the recurrence of violent incidents behind prison walls, which frequently made the national news. Uprisings of political prisoners, internal settling of accounts by the mafia, and the security operations of the gendarmerie often resulted in high numbers of prisoner casualties and the scandalous discovery of vast amounts of weaponry, cell phones, and illicit drugs smuggled inside prisons. The incidents that leaked to the media raised many questions and occasioned much public criticism (both national and international) concerning the state’s human rights abuses, lack of security in its prisons, and the disproportionate use of force by the security forces to impose order. These incidents put democratically elected governments into a much more difficult position than the military. They troubled national claims of having achieved civilianization and democratization in the postcoup era to the outside world, while, internally, they weakened popular faith in the state’s ability to protect the lives entrusted to its control and increased government officials’ own worries vis-à-vis their electoral constituencies about their ability to solve the thorny issues enveloping the criminal justice system.

These concerns were no doubt aggravated by the mass hunger strike of political prisoners launched in October 2000. The sheer numbers of prisoners who participated in the strike, coordinated across the country in forty prisons, and the militancy with which the prisoners were struggling constituted living proof of the severity and seriousness of the situation in the country’s prisons. For the government in need of formulating an urgent response to the hunger strike, the current unrest in prisons was an alarming symptom of deeper problems that needed large-scale reform, reform that could not be carried out without a parliamentary discussion that generated a broad coalition of support across the political spectrum. Under these conditions, the Turkish Grand National Assembly gathered for a special session devoted to discussing the “prisons problem” on November 21, 2000. The debate in parliament revealed, however, that more than prison reform was at stake. The parliamentarians were quick to diagnose the current situation not simply as a crisis of prisons but rather as a “crisis of sovereignty.” This was because the political prisoners’ resistance was perceived as an outrageous challenge to the state from within those sites allegedly under its most intimate control.

At the special session of the parliament, Minister of Justice Hikmet Sami Türk presented the situation of prisons in austere terms, representing the general sentiment of the coalition government of three parties led by Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit: the social-democratic Democratic Left Party (Demokratik Sol Parti), center-right Motherland Party (Anavatan Partisi), and ultranationalist Nationalist Action Party. Minister Türk admitted that there were serious problems at every level of the penal system, even though a “concentrated effort was being made in order to create an environment that was respectful of human rights, befitting of modern states, [and] to establish order, discipline and security fully in prisons and detention houses.”77

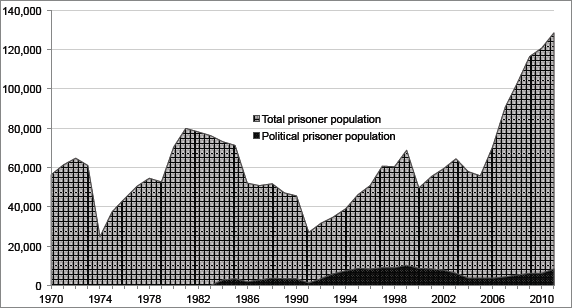

According to Minister Türk, the prison population was now higher than ever before in the history of the republic (see figure 2.1). At the time of his speech, there were 73,748 individuals in prison, exceeding the total capacity of prisons in use (designated for 72,575 individuals).

Overcrowding, Türk opined, resulted from the fact that the pace with which new prisons were being built was not keeping up with the growing numbers of prisoners: every month an additional 372 people were admitted to facilities that were already filled to capacity. Existing prisons were simply inadequate to house the growing prisoner population. Türk did not probe deeper into the reasons why the prisoner population might be growing at such a fast pace. Whether the higher prison population was a consequence of overall population growth, increasing crime rate, widening definitions of crime, more vigilant policing and law enforcement that brought greater numbers of offenders into the criminal justice system, increased numbers of trials with remand, or a host of possible other factors, was irrelevant for the government whose main concern was to frame the “prisons problem” as a technical problem (overcrowding) with a technical solution (new prisons) rather than a political problem (justice) that required social, economic, and cultural reform.

Figure 2.1 PRISONER POPULATION OVER TIME

Compiled from statistical data published by the Ministry of Justice. ABCTGM, “Statistics,” http://www.cte.adalet.gov.tr/ (Last accessed December 1, 2012.)

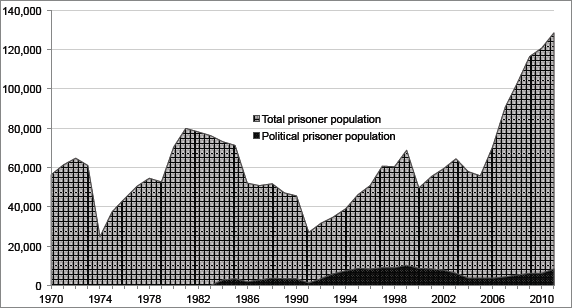

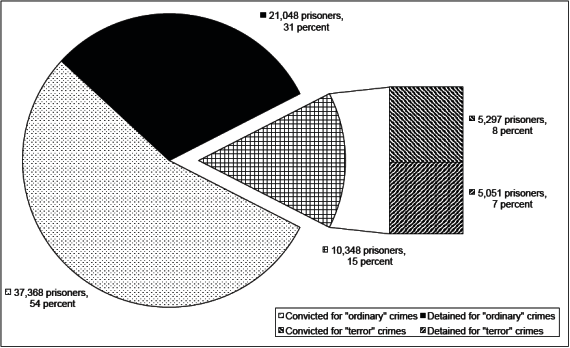

But the swelled prison population was only the surface of the problem. The composition of the prison population was a complicating factor. The political prisoner population of Turkey corresponded to approximately 15 percent or one-seventh of the total prison population (see figure 2.2).78 Around 70 percent of the political prisoner population comprised prisoners associated with the Kurdish struggle (numbering around sixty-five hundred to seven thousand), another 20 percent comprised prisoners with extraparliamentary leftist affiliations (numbering around fifteen hundred to two thousand), while the rest were imprisoned for cases related to radical Islamist organizations and other “terror” crimes.79 The political prisoner population had quadrupled since the early 1990s, and this steady increase corresponded to the promulgation of the antiterror law (see figure 2.3).

The third crucial issue was critical security failures. Originally built outside cities, most prisons had been encircled by residential neighborhoods as urban settlements spread outward. These locations facilitated the escape of prisoners as well as the smuggling of illegal substances and weapons into the prisons. Security failures were also connected to the high rate of prisoners imprisoned for “terror” crimes and the increased activities of criminal gangs, leading to escapes and casualties due to violence among prisoners or violence by state personnel. Only a year earlier in 1999, ten prisoners had died in the security operation conducted at Ulucanlar Prison, Ankara. Even the parliament’s own Human Rights Investigation Commission voiced serious concerns that security forces might have used disproportionate force and resorted to torture during their intervention.80 On the other hand, in the recent riot at Uşak Prison, instigated by the mafia leader Nuri Ergin and his followers (also known as the Nuriş gang), 6 prisoners were killed and thrown out the window, making national headlines. According to the figures provided by the General Directorate of Prisons and Detention Houses, another 16 prisoners had died because they were executed by fellow political prisoners after being tried in the mock tribunals operated by terrorist organizations themselves. In addition to these casualties, in the ten riots that occurred in 1995–2000, nearly 400 prisoners were seriously injured. In these violent incidents, 205 of the prison personnel were also injured and 9 were killed.81

Figure 2.2 INTERNAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE PRISON POPULATION (AS OF 1999)

Compiled from statistical data published by the Ministry of Justice. ABCTGM, “Statistics,” http://www.cte.adalet.gov.tr/ (Last accessed December 1, 2012.)

Figure 2.3 PRISONER POPULATION HELD FOR “TERROR” CRIMES OVER TIME (AS PERCENT OF TOTAL PRISON POPULATION)

Compiled from statistical data published by the Ministry of Justice. See ABCTGM, “Statistics,” http://www.cte.adalet.gov.tr/ (Last accessed December 1, 2012.)

Overall, in the last seven years, 51 prisoners had escaped, 27 prisoners had died in the security operations of the gendarmerie (see table 2.1), 26 prisoners had died because of internal clashes and conflicts, and 12 prisoners had died in the 1996 death fast, adding up to some 116 prisoner casualties. Adding the numbers of prisoners who were involved in conflicts, uprisings, escape attempts, and other infractions, and factoring in the general destitution of living conditions in the prisons, the country’s prisons appeared to be forlorn institutions.

Having sketched out different facets of the “prisons problem,” Minister Türk placed the blame on a combination of factors: deficient physical infrastructure, insufficient financial resources, inadequate and lenient legislation, and understaffing. The inadequacy of existing prisons was obvious enough. But the limited budget allotted to the Ministry of Justice slowed down the construction of new prisons, created delays in the transportation of prisoners to court hearings, and impaired the provision of adequate heating and food for prisoners.82 The legislation concerning the administration of penal institutions was outdated and haphazardly supplemented by decrees and statutes adopted at different times based on conjunctural needs.83 Penal institutions were administered according to the Law on the Administration of Prisons and Detention Houses (Law No. 1721), dating from 1930, and the Law on the Execution of Punishments (Law No. 647), dating from 1965, and various other bylaws, statutes, and executive decrees (such as the Bylaw on the Administration of Penal Institutions and Detention Houses and the Execution of Punishments).84 Recent legislation enabled prisoners to be conditionally released after completing two-fifths of their sentences, and the ceilings imposed on prison terms, Türk argued, made punishment too lenient and annulled any deterrence function. Furthermore, prison staff was largely uneducated and severely underpaid. Prisons were also understaffed in that only 25,122 of the 31,194 positions were filled (while 43,345 positions would have been necessary to administer existing prisons at full capacity). In other words, the prisons were run by only 60 percent of the personnel originally stipulated as required for their proper administration.

However, the root cause of the “prisons problem,” according to the minister, was the spatial organization of the prisons. Prisons were laid out in dormitory-style wards. The size and capacity of wards varied, but they usually housed around thirty to one hundred individuals each. These crowded wards compromised security and order because they made it possible for some prisoners to control and dominate others. Türk argued that wards also allowed prisoners “to act collectively, to create damage in the buildings, to render those in charge ineffective, to succeed in actions such as having the doors left open, taking hostages, extracting tribute, preventing searches, digging tunnels and escaping, and instigating uprisings.”85 The minister claimed that terrorist organizations and gangs used wards to maintain “their group discipline in prisons and detention houses, and furthermore, [to sustain] their relations with the outside [world],” making prisons “ideological training grounds.”86 Prisons had thus been transformed into educational and organizational “headquarters” in which terrorist identities were reinforced, subversive ideologies were disseminated, and new plans to undermine the state were concocted.

Member of Parliament Beyhan Aslan, speaking on behalf of the Motherland Party in the coalition government, described the situation in even more apocalyptic terms:

Today, unfortunately, the prisons in which there are terrorists, mafia and gang members, are not under the sovereignty of the State of the Republic of Turkey. … Prisons are training camps that educate militants for the organization of terrorist offenders, [they are] the command headquarters for gang members and the mafia. There are kings in prisons. Aghas have sprung up in prisons. When the sovereignty of the state was compromised, terrorist offenders, mafia and gang members have become sovereign over prisons with violence, by intimidating the administration with threats, and sometimes, with bribes. The administration cannot carry out body counts, cannot enter wards; the administration is overawed and ousted. The detainees and convicts entrusted to the state are deprived of completing their sentences in peace. … We are openly and clearly pronouncing this: the ward system has become bankrupt.87

Table 2.1 MAJOR SECURITY OPERATIONS IN PRISONS (1995–2000)

Compiled with data from TİHV, İşkence Dosyası; İHD, Sessiz Çığlık; and Demirci and Üçpınar, İzmir Barosu İnsan Hakları Hukuku.