9

Hall of Heroes

In 1808 virtually all German-speaking territory, from the Netherlands to the Russian frontier, was under French control. Every serious attempt at military resistance had failed. At the Battle of Austerlitz in December 1805, Napoleon had resoundingly defeated the Austrians and entered Vienna as conqueror. In the summer of 1806, after a thousand years of existence, the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation had been dissolved. A few months later Napoleon crushed the Prussian army at Jena and Auerstädt, forcing a humiliating surrender. On 27 October 1806 he marched triumphantly through the Brandenburg Gate and entered Berlin (see Chapter 1). And in September 1808, in the central German city of Erfurt, now the principality of Erfurt, and designated part of the French Empire, Napoleon summoned the rulers of Germany to pay him homage in the presence of the Tsar of Russia. Many of those German rulers were now Napoleon’s active allies (see Introduction). The others had been reduced to grudging acquiescence. No effective autonomous German political unit was left.

In circumstances like this, what did it—what could it—mean to be German? And in the face of enduring and effective French military aggression, what opposition was possible?

It was in the days of Germany’s deepest degradation (the humiliation of Jena had taken place, and Germany had already begun to tear itself in pieces) that there arose in the beginning of the year 1807, in the mind of the Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria, the idea of having fifty likenesses of the most illustrious Germans executed in marble. And he commanded the undertaking to be commenced immediately.

The words came from Ludwig of Bavaria’s own manifesto of his defiant dream of re-creating an enduring Germany by honouring its outstanding historical figures. It led over the next few decades to one of the most idiosyncratic expressions of national identity in nineteenth-century Europe—a temple to German-ness built high above the Danube: the Walhalla.

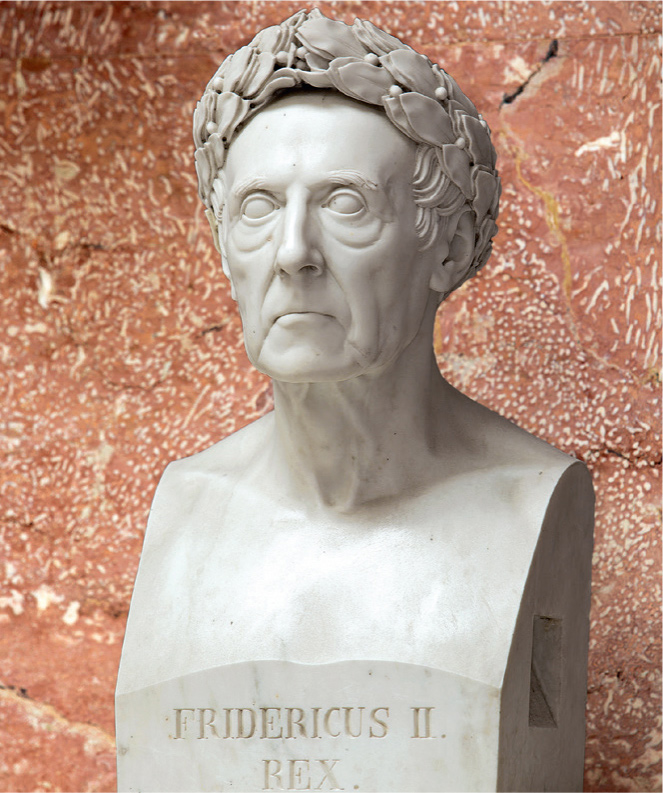

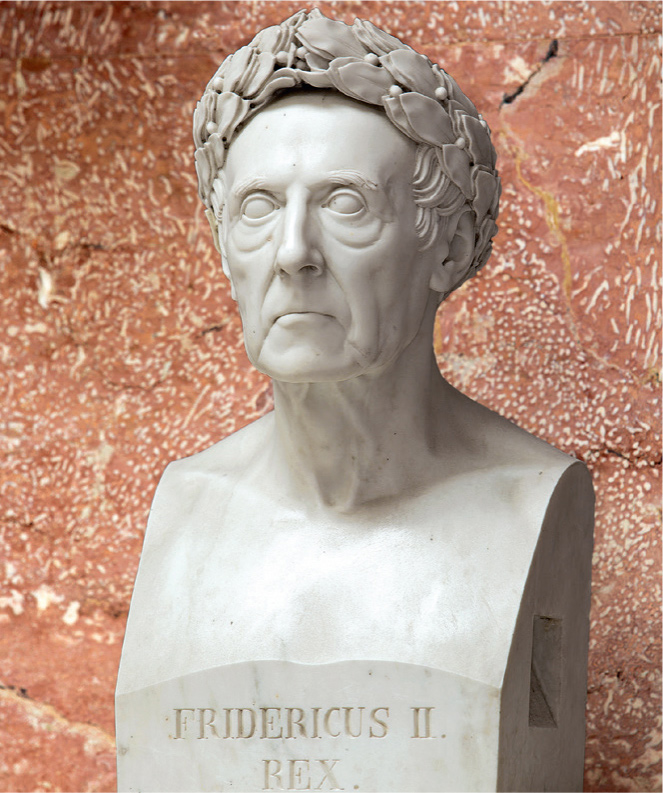

As Crown Prince, Ludwig could not, in 1807, embark on a major building, but he could, as he described in his memoir quoted above, commission portrait busts. In the years between 1807 and 1812, as the German states were, one after the other, humiliatingly forced into alliance with Napoleon in preparation for the attack on Russia, Ludwig charged the foremost sculptors of the day to produce likenesses of Frederick the Great and Maria Theresa, Gluck and Haydn, Leibniz and Kant, Schiller and Goethe. The great spirits of the past—only Goethe was still alive—would give dignity and hope to a defeated Germany. This was history as the highest form of passive resistance, a National Portrait Gallery as a step to national liberation. The Holy Roman Empire no longer existed, but the German empire of the spirit endured. With all the means he could command after he had become King of Bavaria in 1825, Ludwig resolved to build its temple.

In Norse mythology, Walhalla is the majestic hall to which the heroic dead are carried by the Valkyries, to join their predecessors and comrades. In the early 1800s, the legends of the north were in fashion. As the Brothers Grimm rediscovered German folk tales (see Chapter 7) medieval German epics like the Nibelungenlied (the Song of the Nibelungs) were expelled and extracted as part of the national inheritance. Richard Wagner would ultimately transform the sagas of the Vikings and the poetry of the German Middle Ages into his magisterial Ring Cycle, making the Valkyries and Valhalla familiar to every opera-goer, creating perhaps the supreme achievement of German music.

Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria, by Angelika Kauffmann, 1807 (Credit 9.1)

The Gods Entering Valhalla, the final scene of Richard Wagner’s Das Rheingold, print, c. 1876 (Credit 9.2)

Ludwig’s first idea for his Walhalla was that it should be sited in the English Garden in Munich. Later, he decided it should be near the former Imperial city of Regensburg (which had recently been incorporated into the Kingdom of Bavaria), where the Holy Roman Empire had held its parliaments, convening notables from the whole of Germany and beyond. Walhalla was to be a different kind of German Parliament. The Holy Roman Emperor had summoned delegates: King Ludwig now summoned the spirits of great Germans from the past in one stupendous assembly of achievement.

The site chosen by Ludwig and his architect, Leo von Klenze, is spectacular. J. M. W. Turner, England’s great landscape painter, was present at the opening in 1842. Then nearly seventy years old, he was bowled over by it, painting one of his most complex late landscapes, now in the Tate Gallery, and composing some of his worst verse:

But peace returns—the morning ray

Beams on the Walhalla, reared to science and the arts,

For men renowned, of German fatherland.

On a hill rising 300 feet above a secluded stretch of the Danube, facing south, the king and Klenze constructed not a Gothic evocation of the gods of the ancient north, but a version of the Parthenon. Approached from the river, the entrance is reached by a huge monumental staircase, a homage to the Propylaeum in Athens, which leads to the Acropolis and the Parthenon itself. It is impossible not to have the sense of being a humble pilgrim approaching a great shrine. As the building comes into view and the portico with its double row of fluted Doric columns looms above, the message is clear: here the greatest Germans are being inducted into a fellowship with the Ancient Greeks.

Bust of Frederick the Great, by Schadow, 1807 (Credit 9.3)

Bust of Empress Maria Theresa, 1811 (Credit 9.4)

As on the Parthenon, the pediments of the temple start by telling the tribal creation myths. On the north pediment is a colossal statue of the heroic Germanic chieftain, Hermann, shown with his soldiers from different German tribes, all fighting together to defeat the Romans at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in A.D. 9—the first recorded moment of successful German resistance to the invader (see Chapter 7). On the south pediment, 1,800 years on, is the figure of Germania, the embodiment of the nation, surrounded by those who fought Napoleon to free Germany once again from foreign aggression and invasion. The whole history of what the German peoples had achieved, as shown in Ludwig’s building, lies between these two defining moments, of national resistance against the Romans and national liberation from the French.

Inside is a noble, lofty space, about fifty yards long and twenty yards wide, and intensely, joyously colourful. The floor is paved with white and golden slabs, the walls are clad in pink marble, and the wooden ceiling, gold and blue, is held up by pairs of female figures. In Athens, these would be caryatids, but here they are Valkyries, the maidens who in ancient Germanic myth carried dead heroes from the battlefield to their heavenly abode—Walhalla. These particular Valkyries are wearing blue and white, the colours of Bavaria.

South pediment showing the 1813 Wars of Liberation (Credit 9.5)

North pediment showing Hermann at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (Credit 9.6)

The centre of this magnificent building has been left entirely empty, because the purpose of this rich display of colour is merely to serve as backdrop to the 130-odd white marble busts who are the inhabitants of Walhalla—busts with whom we can engage one by one in a dialogue that will lead to an understanding of what it means to be German. The selection criteria were set out by Ludwig himself in his preface to the first guidebook:

To become an inhabitant of Walhalla, it is necessary to be of German origin and to speak the German language. But as the Greek remained a Greek, whether from Ionia or Sicilia, so the German remains a German whether from the Baltic or Alsace, from Switzerland or the Netherlands. Yes—the Netherlands. For Flemish and Dutch are but dialects of Low German. What decides the continued existence of a people is not the place of residence but the language.

Ludwig had found a solution to the perpetual conundrum of Germany’s lack of fixed frontiers: Germany was quite simply all the places where people spoke German. Like the Greek diaspora in the Mediterranean the Germans settled across Europe formed one coherent cultural world.

It was a view widely held after the Wars of Liberation. In 1813, Ernst Moritz Arndt, the first bard of German nationalism, had composed a song that became hugely popular: “Wo ist des Deutschen Vaterland?”—“Where Is a German’s Fatherland?” Verse after verse considers the different candidates—Pomerania and Bavaria, Saxony, Switzerland and the Tyrol—to conclude that wherever the German tongue is spoken, there is a German’s fatherland. The link between language, national identity and shared aspirations, which Ludwig, Arndt and many others articulated for Germany, was mirrored in Britain: Wordsworth, in a sonnet of 1803, considering how the British should respond to French attack, had come to a similar conclusion: “We must be free or die, who speak the tongue that Shakespeare spake.” It was an idea with a long life: in 1937, as war again threatened Britain, Churchill began to compile his History of the English-Speaking Peoples—based on the same assumption as Ludwig’s in Walhalla, that a shared language implies enduring affinities.

Having established the key criterion for admission, Ludwig went on to explain the house rules of Walhalla:

Beginning with the first Great German known, Hermann the conqueror of the Romans, there are in Walhalla the busts only of illustrious Germans, executed by German artists; or, if there are no contemporary likenesses, their names in bronze on plaques. No condition, not even the female sex, is excluded. Equality exists in Walhalla.

In this insistence on equality, there is a striking similarity between Ludwig’s Walhalla and another royal initiative to rally the people against the invader—Frederick William of Prussia’s institution of the Iron Cross and Order of Luise (Chapter 14). In Bavaria and in Prussia, the highest honours were now to be equally available to men and women, and rank was to play no part. It was a notion of equality that in both kingdoms was to remain eloquently symbolic, but emphatically not political.

The plaques above the entrance door immediately demonstrate the quirky, inclusive idiosyncrasy of Ludwig’s choice. They start of course with the Roman-defeating Hermann. Beside him is Einhard, the scholar-historian of Charlemagne’s court: Germany is both valiant and scholarly. Alfred the Great (the English Alfred the Great), Saxon-speaking and so part of this great German family, is also here as the liberator of his country from the Danes. But Walhalla is not a place just for the grand. Beside Charlemagne, first German Emperor, is the plaque of Peter Henlein, of Nuremberg, who, it was believed, had around 1510 invented the first pocket watch (see Chapter 19). This is a very personal pantheon, and one of the great pleasures of wandering around Walhalla is to see who has been invited to this ultimately exclusive party—and who, definitively, has not.

Interior of the Walhalla monument, 1842 (Credit 9.7)

Bust of Catherine the Great, 1831 (Credit 9.8)

Bust of William of Orange (William III of Great Britain), 1815 (Credit 9.9)

Ludwig was understandably generous to his own Wittelsbach ancestors, and to monarchs in general. There might be a hint of snobbery in the inclusion of Empresses Maria Theresa and Catherine the Great, originally a German princess, whose incorporation into Walhalla irked the Russians (the French similarly bristled over the presence of Charlemagne). Walhalla in fact was the only pantheon of its time to include a significant number of women, as well as having a strong supporting cast, including Germania, the Valkyries and the Victories as decorative figures. All this was fitting, perhaps, for a monarch notorious for his fondness for women—it was the scandal of his liaison with the beautiful courtesan Lola Montez that contributed to Ludwig’s downfall in 1848. As King of Catholic Bavaria, Ludwig naturally added saints and missionaries of both sexes, but in general those first two plaques, to Hermann and Einhard, set the tone, and military and cultural heroes account for most of the guests.

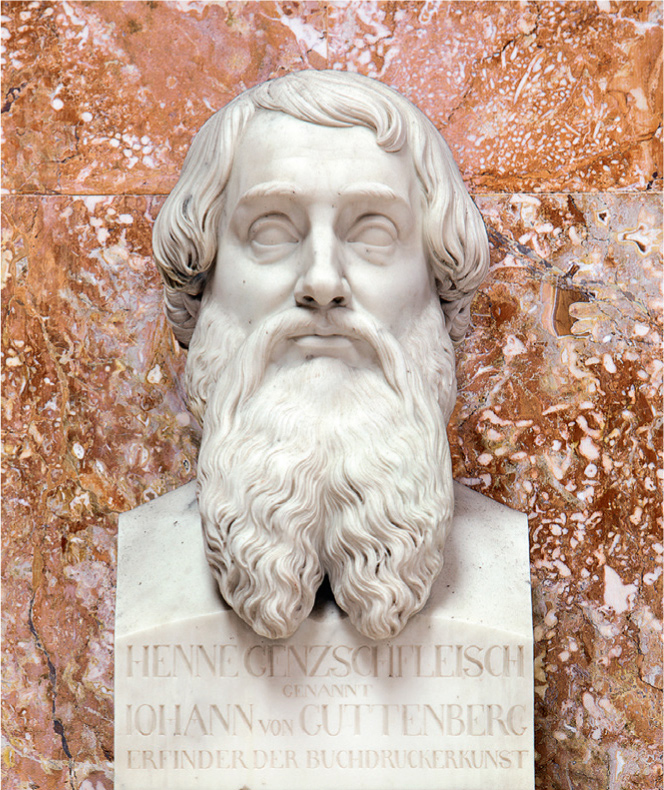

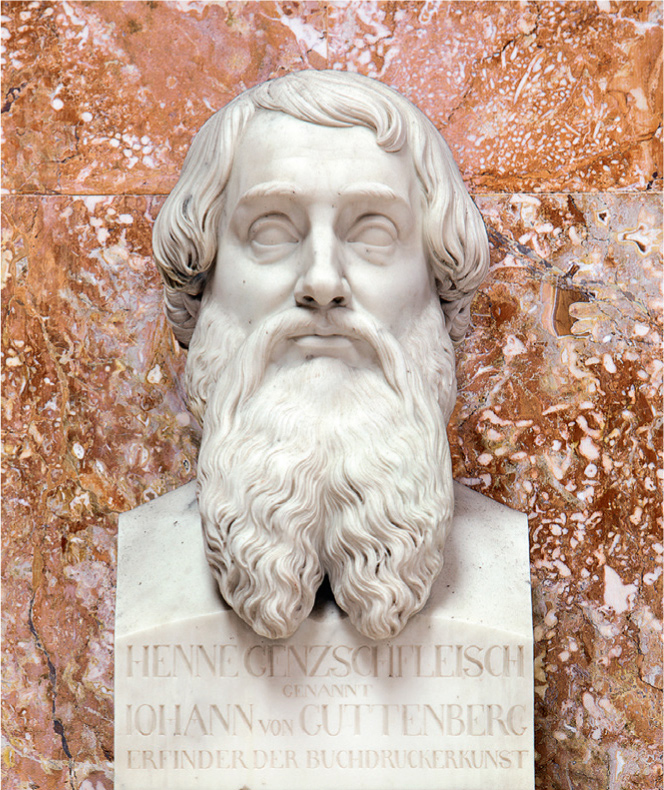

Bust of Gutenberg, 1835 (Credit 9.10)

Bust of Luther, 1831, not installed until 1848 (Credit 9.11)

Intriguingly, the busts are not organized in any coherent chronological order, so the visitor keeps moving backwards and forwards through time and across space, adding to the almost dreamlike sense of encountering characters refracted through the erratic prism of Ludwig’s historical imagination.

In spite of being both Prussian and Protestant, Frederick the Great was among the first selected for this Bavarian celebration. He had fought against, and defeated, many of his fellow Germans, but he had rescued his country in the Seven Years’ War and made it into a European power. Near Frederick sits Blücher, a fellow Prussian, who fought with Wellington at Waterloo. And as the notion of German-ness here is a very wide one, we find a Russian general of Scottish descent who also fought against Napoleon—Barclay de Tolly—who slips in as a native German speaker. William of Orange, William III, King of Great Britain, is—unsurprisingly—here, Dutch being for Ludwig a version of German, and William himself a German prince of the House of Nassau, who had, a hundred years before, led the European coalition to fight Louis XIV. Again and again the point is made: from Charles Martel defeating the Arabs at the Battle of Tours in 732 to the Battle of Waterloo, Ludwig chooses to celebrate individuals who spoke German and who had, through the centuries, fought bravely for their country.

On the cultural side, the great musicians are represented in force—Beethoven and Mozart, Haydn and Handel; the great writers and philosophers—Goethe and Schiller, Erasmus and Kant; and the great inventors and scientists—Gutenberg and Copernicus, as well as Henlein, and Otto von Guericke, inventor of the vacuum pump and the famous Magdeburg Hemispheres. The painters once again make clear just how wide Ludwig’s idea of German-ness was: beside Dürer and Holbein are Rubens and van Dyck, both of German (in this case Flemish) tongue, and so perfectly proper residents of Walhalla.

But the real debate about who got to be in Walhalla did not concern literature or philosophy, science, music or the arts. It was about religion. When Walhalla opened in 1842, the most striking absence from among the 160 figures originally chosen to represent 1,800 years of German history—and widely commented upon at the time—was Martin Luther. Nobody of course would have disputed that he was a great religious figure, but for the Catholic Ludwig, king of the intensely Catholic Bavaria, Luther was a profoundly divisive figure in the history of Germany, responsible for a national schism that precipitated the cataclysm of the Thirty Years’ War and the destruction of German religious unity. The Oxford historian Abigail Green, who has studied the use of history in the forging of national identities in German states after 1815, explains:

“The religious balance in Germany shifted when the Holy Roman Empire died. It was not the case that the number of Catholics and Protestants changed, but in the Holy Roman Empire there had been many more Catholic polities, mostly small. After the Holy Roman Empire dissolved, there were more Protestant monarchs and a lot of states became religiously mixed. As the debate developed over what kind of Germany would come to be, the religious element was very important. For Protestants, Luther was clearly the most significant German—Germany’s great contribution to world culture. But if you were a Catholic, Luther and Protestantism appear as a very divisive force. They divided the Christian community and they divided the German nation. And the legacy of the wars of religion, the Thirty Years’ War, in particular, was terribly bitter.”

A bust of Luther was in fact originally commissioned and sculpted, but then excluded at the last moment. Luther did not enter Walhalla until the year of liberal revolutions, 1848—the first to be added to Walhalla after it had opened, conceded by an increasingly unpopular Ludwig shortly before his forced abdication. Today, in reparation, Luther sits in a prime position beside Goethe. But, as Abigail Green points out, the religious debate went wider than Catholic and Protestant:

“Only Christian Germans were, at the beginning, introduced into Walhalla by Ludwig. It is not realistic to expect that Ludwig would have put Moses Mendelssohn in, for example: but, at the same time, Mendelssohn was a giant of the German Enlightenment, one of the most significant figures in modern Jewish history, and a great friend of the writer and philosopher Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, who did make it in. His absence is noteworthy, and there are still now other notable Jewish absences, like Freud and Marx.”

Most of the later arrivals at Walhalla are fairly unsurprising. There is nothing controversial about the arrival of Max Joseph von Pettenkofer, the pioneer of public health, or Wilhelm Röntgen, the inventor of x-rays. Any house of German memories must give a special place to music. The anonymous author of the Nibelungenlied is honoured in a plaque high on the wall, and among the busts you find, as you would expect, Wagner, whose later musical Valhalla has far outstripped Ludwig’s building in worldwide fame. His bust was installed in 1913, followed three years later by Johann Sebastian Bach, a surprisingly tardy arrival. But one of the later musician guests is perhaps worth pondering: Anton Bruckner. His was the only bust to enter Walhalla during the Nazi period, and he is here not just as a great composer, but because he was born in Linz in Austria—near to where Hitler spent his childhood. The incorporation of Bruckner into Walhalla, at a ceremony attended by the Führer himself, was one way in which the cultural aspirations of Ludwig were taken over by the Third Reich. But interestingly—surprisingly—it was the only one. It might have been expected that Hitler would exploit to the full Ludwig’s idea of a temple to great Germans who had changed the world but in fact he left it relatively untouched.

Installation of the bust of Anton Bruckner, 1937. Hitler is standing forward, bottom left. (Credit 9.12)

Unveiling of the bust of Heinrich Heine by the Bavarian Prime Minister, Horst Seehofer, 28 July 2010 (Credit 9.13)

The lower range of busts, almost at eye level, are now arranged in the order in which they arrived in Walhalla. There is nothing especially startling, after Luther, until the addition made in 1990: Albert Einstein, the first Jew in Walhalla. This was perhaps the moment at which it became clear that who is in Walhalla is still a matter of real importance and public debate. In this building, Germany—at least part of Germany (Bavaria)—is still deciding what kind of history it wants to write, which memories matter. Few countries offer a similar forum for the shaping of a national story.

The installation of Einstein, a Jew who left Nazi Germany to live in exile, was followed by Konrad Adenauer, the great architect of post-war democratic Germany. But it is perhaps the last three busts in Walhalla that raise the most interesting questions. The nineteenth-century poet Heinrich Heine, acerbic, lyrical and ironic, had long been absent—partly of course because of his Jewish descent, but also because he was a severe critic of the very idea of such a shrine to the great. He thought Walhalla absurd, publishing a satirical poem mocking Ludwig for building this “field of skulls.” On 28 July 2010 the mocker joined the elect. But his bust is like no other. Running through the marble from the cheekbone to the middle of the chest is a split: the sculptor has tried to find a way of showing the irresoluble ambiguity implicit in having Heine, the critic of Walhalla, present in this space.

Surely the most difficult of recent decisions, perhaps the most difficult of any decisions about inclusion in Walhalla, concerns Germans who lived and died under the Third Reich. Included is the bust of the Jewish-born philosopher Edith Stein, who converted to Christianity, was murdered in Auschwitz and was later canonized by the Roman Catholic Church. Abigail Green:

“It is important to realize that the people now deciding who goes into the Walhalla are the Bavarian State Parliament. The choice seems, to me, to be quite conservative. The absence of Marx, clearly such a globally significant figure, is striking. These decisions reflect the particular make-up of Bavaria, which has always been very strongly Catholic. Edith Stein is a curious choice in a lot of ways. You can see why she is there: she is of Jewish birth, a Holocaust victim, and also an important philosopher. But what about Hannah Arendt, who clearly had much more global significance? It does speak very much to the fact that there are still competing narratives about what Germany is and what Germany was, and what the German past consists of—and these vary locally, and also in religious ways.”

As you move round Walhalla, the final interlocutor in this monumental chronicle of the achievements of the German-speaking world is Sophie Scholl—a non-violent resister to Hitler who was sentenced to death by the Nazis. Her bust stands above the last plaque, the final plaque at this level, engraved with these words:

Bust of Sophie Scholl with plaque to the Resistance, 2003 (Credit 9.14)

Im Gedenken an alle, die gegen Unrecht, Gewalt und Terror des Dritten Reichs mutig Widerstand leisteten.

In memory of all those who courageously offered resistance to the injustice, the violence and the terror of the Third Reich.

In this building, as in so many others in Germany, the visitor can read a nation’s struggle to make a history that has coherence and integrity.

There are many things about Walhalla that seem perverse or puzzling, but particularly striking is the choice of architectural style. High on the wall is a plaque to the unknown architect of Cologne Cathedral, while there is a bust of Erwin von Steinbach, architect of Strasbourg Cathedral, whom Goethe hailed as the great master of German Gothic architecture (Chapter 4). While Ludwig was building Walhalla on the Danube, the Prussians, by the Rhine, were completing the medieval gothic Cologne Cathedral as a symbol of the ancient Germany which must be restored. And yet Walhalla, which is all about German-ness, is not in a German gothic style at all, but in a Greek style, with eclectic flourishes that speak to ancient Egypt, Babylonia and India. Abigail Green again:

“Classical architecture gave status. The French always identified with the Romans, either the Roman Republic or the Roman Empire. But the Germans always identified with the Greeks. They thought they were, like the Greeks, culturally superior, if militarily perhaps less hard-hitting than the Romans or the French. They also identified with Greek plurality: there were lots of different Greek city-states, in the same way as there were lots of German states. They thought the Greeks had a particular attachment to liberty, which they also saw as being particularly German. So I think the choice of a Greek architectural style for Walhalla is obvious, but significant.”

For the Bavarians, this identification of Greece with Germany had one very particular resonance. While Ludwig I was building Walhalla, his second son, Otto, was chosen by Britain, France and Russia to be the first king of independent Greece, recently liberated from Ottoman rule. Bavarian Otto in many ways shaped the Greece we know today. He moved the capital to Athens, then embarked on the restoration of the Acropolis. The public buildings of modern Athens are strikingly similar to those of modern Munich, as both father and son set out to build two ideal Greek/German cities for the nineteenth century. In the late 1830s both the Parthenon in Athens and the Parthenon on the Danube were building projects of the Bavarian House of Wittelsbach. In this, as in many other respects, nineteenth-century Germans thought of themselves as embodying the virtues of ancient Greece. To this day a grammar-school in Germany is called, in open homage to Greek education, a Gymnasium.

Bust of Erwin von Steinbach, 1811 (Credit 9.15)

“Greetings from Munich!,” a 1960s postcard (Credit 9.16)