7 |

WAR – II |

New Construction1

THE BAYERN CLASS

The 1915 programme as originally formulated had included one battleship (Ersatz-Kaiser Wilhelm II, to be Württemberg [ii]2), which was laid down in early 1915. Ersatz-Kaiser Wilhelm II represented a further refinement of the modified design used for the 1914 Sachsen-to-be, but with the decision taken from the outset to fit an all-steam plant, and thus omitting the cylinder-head glacis installed in that ship; in addition, protection was slightly enhanced by fitting a 200mm aft conning tower.

In late 1916, based on lessons from Jutland, modifications were ordered for both new vessels of the class. Sachsen had just been launched, and as she was already overweight, all that could be done was to enlarge the after conning tower. Ersatz-Kaiser Wilhelm II/Württemberg was still on the stocks, and thus more could be done: in addition to the enlargement of the after conning tower, the armour deck over the magazines and transmitting station was thickened from 30mm to 50mm.

Neither ship was to be completed. Sachsen had been launched five months late and Württemberg a year beyond the date planned when laid down, work being effectively stopped early in 1918. Although Sachsen was sufficiently advanced for her turrets and the guns of the superfiring turrets of her main battery to be put in place, there was no real intent to complete either of them until after the end of the war.3 The diesels earmarked for Württemberg’s generators went instead into the submarines Bremen, U151, U156 and U157.

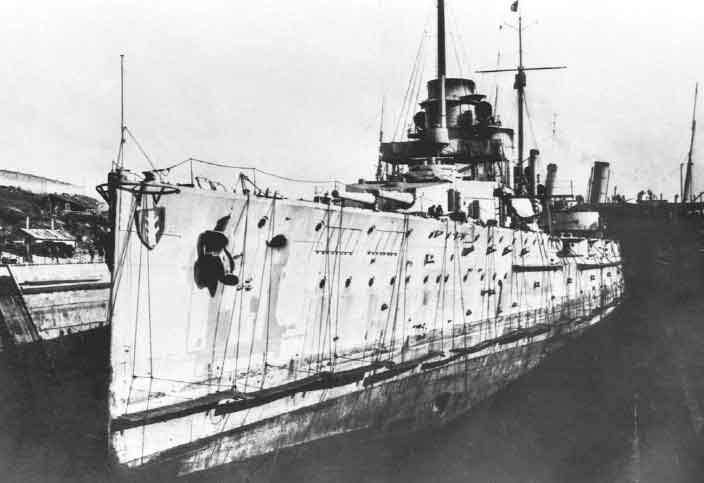

Sachsen (ii) was well-advanced but still incomplete at the end of the war, although with her machinery installed and some of her main battery in place. She is shown here in 1920 following the removal of her belt armour; such guns as had been installed had been taken off in 1919. (Author’s collection)

THE MACKENSEN CLASS

The 1915 programme contained a further large cruiser, Ersatz-Freya.4 While no further Bayerns were planned, the loss of five large cruisers by January 1915 meant that replacements were added to that year’s programme, with the original intention that they should all be simple repeat-Mackensens. In April, the idea emerged that at least some might be to a modified design, but the loss of yet another large cruiser in October made the construction of new ships urgent. However, in the Emperor’s view, only the loss of Blücher had a direct impact on the High Seas Fleet, and thus only her replacement should be prioritised. Ersatz-Blücher (to be Graf Spee) was thus laid down in November, with the other replacements postponed until the end of the war. The Emperor also revived his long-held belief that capital ships be in future built to a unified ‘fast battleship’ design, rather than perpetuating the existing battleship/large cruiser split. New orders were also opposed by the Reichstag, in view of the lack of activity by the big ships to date and escalating prices, with the Mackensens now looking to cost 50 per cent more than the last of the Derfflingers.

Nevertheless, the four outstanding replacements were ultimately included in the 1915 war programme (Ersatz-Friedrich Carl [also referred to as Ersatz-A], Ersatz-Yorck, Ersatz-Gneisenau and Ersatz-Scharnhorst), the first being laid down in November 1915, at the same time as Ersatz-Blücher. Ersatz-Yorck was laid down in July 1916, but the other two were never laid down; a further replacement ship, Ersatz-Prinz Adalbert was never begun. All fell victim to a shortage of manpower, which delayed the launch of Mackensen and Graf Spee into 1917 (as was also the case with the Bayern-class Württemberg), with the next three still on the stocks at the end of the war, all having been essentially suspended since the beginning of 1918.

While Ersatz-Friedrich Carl/A and earlier ships all proceeded in accordance with the final Mackensen design (with minor changes such main gun mountings upgraded to C/15 standard, ultimately with 28° elevation), Ersatz-Yorck, Ersatz-Gneisenau and Ersatz-Scharnhorst were all redesigned, becoming a new class (see below). Mackensen, Graf Spee and Ersatz-Freya also received additional armour in late 1916, 30mm plate being added over the magazines and transmitting station (as in Württemberg), as well as over the armour deck aft of the citadel and the lower parts of the barbettes. They also had their aft conning towers enlarged (as in the last two Bayerns) and two 15cm guns deleted in compensation. Ersatz-Friedrich Carl/A was more extensively altered, with new thicker plates used to enhance the armour rather than adding a laminate, and some areas thickened over and above the final level of armouring of her sisters. It was also planned to replace the gearing with Föttinger hydraulic transmissions, which had been trialled in the Hamburg-Amerika Line 2150t ferry Königin Luise (sunk as a minelayer on 5 August 1914), and were being installed in their 52,000t Tirpitz (ex-Admiral von Tirpitz, launched 1913; later the British Empress of China/Empress of Australia). They apparently proved less than successful in the larger vessel, the ship’s whole machinery outfit being replaced in 1926-7.

As they were never officially launched, the second pair of Mackensens never officially received names: Ersatz-Freya was certainly to have been named Prinz Eitel Friedrich, but it is unclear as to the intended name of the final ship, both Fürst Bismarck and Scharnhorst having been reported as possibilities. Of the two ships actually in the water, Mackensen still required fifteen months more work when work was stopped, with part of her armour installed. Graf Spee, although started much later, was more advanced, with her boilers, the armour of all four barbettes and twelve casemates installed, with the main belt complete from aft to midships, a year from being finished.

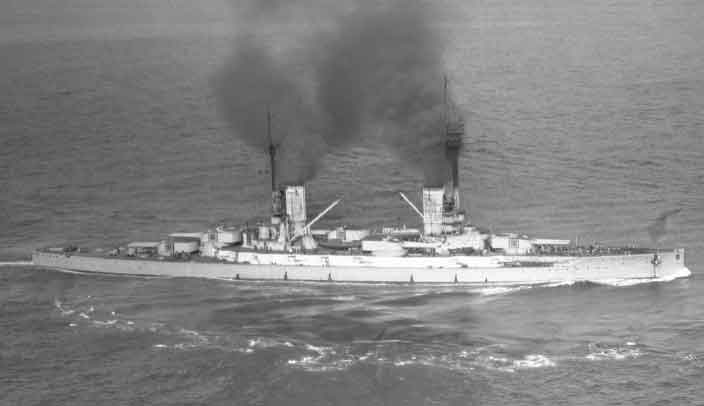

Württemberg, on the other hand, was still without turrets and most of her superstructure at the end of the war, although her boilers (but not turbines) were in place. She is seen here with her armour removed. (WZB)

In a similar state at war’s end was Graf Spee, shown here at her launch on 15 September 1917. (BA 183-R33232)

THE ERSATZ-YORCK CLASS

On 17 March 1916, Admiral von Tirpitz was replaced as State Secretary by Admiral Eduard von Capelle (1855–1931), and a month later a meeting considered the design of the outstanding Ersatz-Prinz Adalbert (to be programmed for construction under the prospective ‘normal’ 1916 [later 1917] programme – not the war emergency programme under which the later Mackensens had been ordered), and any follow-on vessels. Three schemes, GK1, GK2 and GK3 were put forward, of 34,000–38,000t, with eight 38cm guns, a speed of 29–29.5kt and a third of the boilers oil-fired. The consequent discussions questioned the wisdom of constructing the whole of the Mackensen class to their original design, the proposal being made by the Navy Office that the last three (if possible last four) should be stopped and replaced by a new design, GK6 (an up-armoured 28kt version of GK1). This having been rejected, in August it was reiterated that the ships should be built to the original design (Ersatz-Yorck was laid down that month).

However, at the end of October, it became known that the new British battlecruisers Renown and Repulse would be armed with 15in [380mm] guns, and that the projected US battlecruisers might have 16in [406mm] guns, meaning that the calibre of the guns of the Mackensens was once again revisited. Accordingly, Ersatz-Yorck, Ersatz-Gneisenau and Ersatz-Scharnhorst were redesigned to take eight 38cm guns (Ersatz-Friedrich Carl/A proved to be too far along to be extensively altered). The redesign was kept to the absolute minimum to allow the material already assembled on the slip for Ersatz-Yorck to be employed.

Thus, although displacement rose by 2500t, and the hull was slightly lengthened, machinery remained unaltered (with speed reduced by 0.75kt), but with the uptakes now trunked into a single funnel following the deletion of a compartment that had previously divided the boiler rooms into two groups. A pair of 15cm guns was deleted amidships, while the torpedo tubes were reduced to three, at the bow and on the beam just abaft the boiler rooms (possibly to be of a new 70mm calibre). The anti-aircraft battery remained eight 8.8cm. However, although the intent had been to complete them during 1919, all work on the three ships was suspended before the end of 1917; the material assembled on the berth for Ersatz-Yorck was dismantled in early 1920. The diesel generators intended for Ersatz-Gneisenau were used to engine the submarines U151–154.

NEW BATTLESHIPS

Before the war, sketches for potential battleships for the 1916 programme had been drawn up, with ten or even twelve 38cm guns, with both all-twin and a mixture of twins and quadruples considered, the escalation being an insurance against Britain going beyond the eight 15in in the Queen Elizabeth and Royal Sovereign classes. Work seems to have stopped on these designs before the outbreak of war.

However, in April 1916, three battleship designs (L1–3) were put forward in parallel with the GK1–3 large cruiser series. They were of similar size, but of 25/26kt speed, thicker armour and, in one case (L2), ten 38cm guns. However, it was not until the postponement of new-construction large cruisers, and the completion of the redesign work for the Ersatz-Yorck class that serious attention was paid to them. Armament options put forward were eight 42cm, ten 38cm and eight 38cm guns, the first two limited to 22kt, but the third to be capable of 25kt. They were based on twin turrets, although the General-2 Office argued for the advantages of quadruple turrets (as were already being used for the French Normandie class).

Four basic ~42,000t designs were issued around the end of 1916, L20b with eight 42cm, L21b with ten 38cm and L22c with eight 38cm. By August 1917, the eight-42cm option was the preferred one, with schemes L20e and L24 put forward, differing principally in that the latter had an extra 1.5kt in speed, requiring a 3m longer hull and an extra pair of oil-fired boilers (and thus a wider funnel). With further development (and growth), schemes L20eα and L24eα, displacing 44,500t and 45,000t were produced in October and formally submitted in January 1918.

Compared with earlier battleships, the secondary battery was reduced to twelve guns, and L24eα had an additional pair of torpedo tubes, placed above-water. Armour was broadly on Bayern lines, but with some rearrangement. When considered by the Emperor, he returned to the recurring theme of the need to rationalise to a single kind of capital ship, together with the impossibility of continuing the continuous increase in size of ships. He therefore directed that a faster vessel should be produced by deleting the forward superimposed turret and the submerged torpedo tubes.

CinC High Sea Fleet subsequently queried whether triple or quadruple turrets might save enough weight to reach 30kt, delaying further design work until the summer of 1918, when the studies indicated that there would be few worthwhile savings, while rate of fire would be negatively impacted. Accordingly, two designs were put forward, one with eight 42cm and a trial speed of 26kt (essentially L20eα), and another with six guns and a speed of 28kt. In the end, on 11 September 1918, it was agreed that L20eα should be the basis for the next German battleship, to partner a new large cruiser, the desire to replace both with a single ‘large combat ship’ having been overtaken by practical considerations (see just below).

FROM LARGE CRUISERS AND BATTLESHIPS TO LARGE COMBAT SHIP

In considering how the lessons of Jutland might affect future designs, a key constraint remained the Wilhelmshaven locks, with the III. Entrance’s capacity of 235 x 31 x 9.5m the principal one: any larger ship would need a new lock, but basin-size and water-depth in Jade and Elbe rivers were also problematic.

The Navy Office was now keen (as the Emperor had long been) to produce a fast battleship (‘large combat ship’ [Großkampfschiffe]) to supersede both battleships and large cruisers in future programmes, but CinC High Sea Fleet objected, stating that his need was for faster large cruisers (having significantly overestimated British battlecruiser speeds at Jutland), not to mention vessels that could match the gunpower of the Renowns and overcome the protection defects revealed by Jutland. The Navy Office pointed out that the CinC’s desiderata could ultimately add 20,000t to the existing Mackensen design, and that a moderately modified scheme GK6 was probably the best that could be achieved without a new Wilhelmshaven lock.

Such a new lock was approved in October, but it would be six years before it could be completed; thus any new construction of large cruisers would have be postponed for two years to allow the coincidence of their completion and that of the new lock. It was in this context that the decision to complete the Ersatz-Yorcks with 38cm guns was taken.

Designs to give form to the ‘large combat ship’ concept were produced during the first months of 1918. They were numbered in a GK-series in which the ‘GK’ now signified ‘Großekampfschiffe’, rather than ‘Großkreuzer’, and whose fourdigit number encoded the key features of the design. Thus, the first two digits represented the displacement in thousands of tonnes, the third digit indicated the number of main battery turrets and the fourth was the serial number for that size of ship – accordingly, ‘GK3023’ was the third design for a 30,000t, two-turreted ship. All discarded the tripod foremast and light main seen in the Bayerns and Mackensens in favour of a pair of heavy tubular masts of the kind introduced in Kronprinz, thus giving two elevated fire control positions, each equipped with a rangefinder, clearly learning the lessons of the war in the North Sea. All also replaced the former 8.8cm AA guns with a new 15cm AA mounting, presumably recognising the increasing potency of the air threat.

The designs were all intended to achieve a minimum of 30kt, with various combinations of armament and protection, in most cases still within the dimensions permitted by existing dockyard infrastructure. Two, however, GK4931 and GK5031, added a further 40m of length after the approval of the fourth Wilhelmshaven lock.

These studies indicated how far high speed imposed major penalties elsewhere in a ship’s design. The smallest of the schemes, GK3021 and GK3022 (seemingly inspired by the British large light cruisers of the Courageous class), were already at a displacement regarded pre-war as the absolute maximum, and were restricted to four 35cm and four/six 15cm and a main belt of minimal (and very un-German) 100mm or 150mm thickness to accommodate the huge machinery plant needed to achieve their intended speeds. This comprised respectively thirty-two boilers for 140,000shp = 32kt and forty-eight boilers (half above the armour deck, as in one iteration of the US Constellation class battlecruisers) for 200,000shp = 34kt, the space dedicated to boilers reflecting an unwillingness on strategic grounds to move to an all-oil fit.

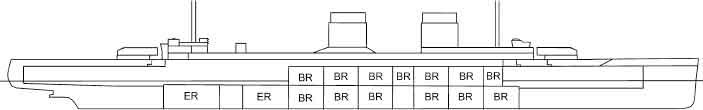

Layout of large combat ship Scheme GK3022 to with its double-tier boiler rooms. (Author’s drawing)

Another 5000t bought 38cm guns and 300mm armour, with another 5000t to get 42cm guns. A displacement of 45,000t allowed an increase in main battery to six 42cm guns (and 350mm armour), with a further pair of guns possible if the main belt maximum thickness reverted back to 300mm. The huge GK4931 and GK5031 reverted to six guns and 350mm armour, the latter requiring 220,000shp to achieve her 32kt speed. What all this work did was to demonstrate that the combination of high speeds with the kind of armament and armour desired by the High Seas Fleet were impracticable in the face of current infrastructure constraints. Accordingly, the last of the series of design-studies were once again designated in the L-series as battleships, L27 of May 1918 reverting to 45,000t and carrying six 42cm guns and a 350mm belt at 29kt, and L28 of June shaving another 500t off the displacement (and 2m off the beam), with a speed of 28kt. All this contributed to the decision to retain the separate battleship and large cruiser categories for the first post-war capital ship programme, with the decision as to the priority reserved to the Emperor.

War Modifications

RIG AND FIRE CONTROL

As already noted, as older ships mobilised, their rig was brought up to current fleet standards where this had not been done before the war. Even modern ships underwent some modification aloft, to provide an elevated spotting position on the foremast. This was being taken even further with new construction, with the tubular mast fitted in Kronprinz, and the tripod masts projected for the Bayerns and Mackensens.

From the summer of 1915, a series of further updates began to be applied, including the installation of a director-type system, the ‘bearing-indicator’, which allowed all guns to be concentrated on a single target. The first vessels to receive the fire-control update were Großer Kurfürst, Moltke and Von der Tann, in June, followed by Friedrich der Große and Ostfriesland. After Jutland, to tie in with the increase in gun ranges (see below), some vessels were fitted with new rangefinders, in particular the Kaisers and Königs. The latter also began to be retrofitted with the heavy tubular mast already installed in Kronprinz, the remaining three Königs and the two Kaisers fitted as flagships (Friedrich der Große and Kaiser) having had them installed by the end of the war. Markgraf also received an admiral’s bridge at this time), while the two Kaisers also had their bridgework extended (Friedrich der Große’s forefunnel casing being consequently raised by a further 1.5m).

König as refitted with her new foremast; as built, she could be distinguished by her flagship bridge, also retrofitted in Markgraf when she received her new mast; Großer Kurfürst also had her bridge enlarged at this time, leaving only Kronprinz (Wilhelm) with her original simple form. (Author’s collection)

While new-construction vessels received tripod foremasts to support an enlarged fire-control position, only one ship was so retrofitted: Derfflinger as part of her extensive post-Jutland repairs. The mast had exceptionally splayed legs, required to fit it into the existing structure. In addition it required the re-siting of her foremost pair of searchlights from the fore funnel to a platform surrounding the tripod, while a further unit was added high up on the front of the mast. Although fitted with tripods from the outset, the platforms on the masts of the Bayerns underwent a number of modifications during the ships’ lives, each having different arrangements by the end of the war.

Kaiser on 6 September 1918, with her new tubular foremast. (BA 134-B0058)

Derfflinger received a heavy tripod mast during her post-Jutland refit. (Author’s collection)

GUNNERY CHANGES

Early in the war the new threat of aircraft led to a progressive replacement of the four 8.8cm guns atop ships’ after superstructures by the same number of 8.8cm/45s on C/13 anti-aircraft mountings. The number of such guns was, however, reduced to two in certain of ships before the end of the war. Even though the Bayerns were designed with no fewer than eight 8.8cm AA guns, Bayern and Baden completed without any, and eventually mounted only four each (see pp 97–8, above), suggesting doubts as to their utility. On the other hand, the clear lack of utility of the low-angle 8.8cm weapons led to their progressive removal from operational ships, Derfflinger for example losing those under her bridge in 1915, and those around ‘C’ turret during her post-Jutland refit. The old ships of the II. Sqn had the forward pair of 8.8cm guns on the after superstructure replaced by 8.8cm/45 anti-aircraft weapons during the summer of 1916.

After Jutland, the elevation of main-battery guns was increased to reflect the experience of that battle, by lowering the trunnions of the guns, resulting in a higher elevation but lower depression (see p 244). The battle had finally shown that the conception of short-range melee that had so long underpinned German capital ship armament policy had been a chimera, a realisation reflected in the upgunning of Ersatz-Yorck and the planning for 42cm armed ships for the future.

OTHER CHANGES

Unlike the Royal and US Navies there was, as already noted, no aspiration to switch to oil firing, except indirectly though the fitting of cruising diesels to the latest battleships. Apart from concerns at the security of supplies, there was also the fact that coal bunkers played a particularly important part in the underwater protection of capital ships, with some of the bunkers formally ‘protective’ ones. On the other hand, some of the boilers of the Nassau and Helgoland classes were fitted for oil firing, to match them with the newer battleships, although this was not extended to the contemporary large cruisers, which remained entirely coal fired. This presented problems, as German coal was no match for the Welsh steam coal that had been used before the war, both in thermal efficiency and the residue left behind that greatly increased the need for cleaning, conspiring to make it all but impossible for the ships of the I. SG to exceed 24kt under wartime conditions.5

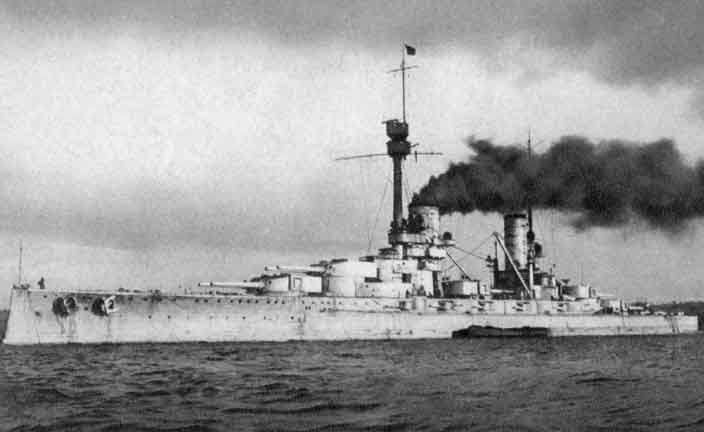

The last battleship additions to the High Seas Fleet were Bayern and Baden, shown here together at sea, with the fleet flagship Baden in the foreground. (Author’s collection)

After Jutland, torpedo nets were deleted as liable to foul propellers in battle (cf. Derfflinger’s experience, p.122), as well as of marginal use against the latest torpedoes (British ships had unshipped them even before Jutland). The only ships that subsequently carried such nets were those assigned to Sound Guardship duty, which spent much time immobile in an exposed position. These were all vessels which had not previously had them, so when Lothringen recommissioned for the role in July, they had been added as part of a refit which had also reduced her secondary battery to ten guns and landed most of her tertiary weapons. Hannover also received them when she relieved her halfsister in the guardship role. Baden and Bayern both had their forward torpedo flat stripped and subdivided following mine damage to the latter in 1917, when its existence had threatened her survival (p 131).

War modifications were thus generally minor amongst the ships dealt with in this book. On the other hand a major reconstruction was proposed for Roon during 1917/18, through which she would be converted to a seaplane carrier. This was along similar, but more elaborate, lines to the refit given to the light cruiser Stuttgart from February to May 1918, and would have involved cutting the hull down by one deck from just aft of midships to make the deployment and recovery of aircraft easier, and erecting a hangar aft of the funnels. All existing guns were also to be removed and replaced by six new 15cm/45 single weapons. Six 8.8cm/45 anti-aircraft guns were also to have been fitted; the conversion was estimated as taking twenty months. However, it was instead decided to convert the incomplete Italian liner Ausonia into a ‘true’ aircraft carrier,6 although this was also never implemented.

Friedrich der Große (seen here at Scapa Flow in 1919) was relieved by Baden as fleet flagship and became the flagship of the new IV. Sqn. She was one of two ships of her class to be refitted with a heavy tubular foremast, and also had an enlarged bridge to reflect her flagship role. (C W Burrows, Scapa with a Camera [1921], p 107)

Operations 1916–1918

THE NORTH SEA 1916–1917

The Fleet after Jutland

The II. Sqn was formally removed from the High Seas Fleet on 1 December 1916, although it continued to exist into 1917. The ships were employed in various guard and special duties roles until the first half of 1917 when they began to pay off. The II. Sqn itself was disestablished on 10 August 1917 and the flagship, Deutschland, paid off a month later. Only Hannover, which replaced Lothringen as guardship in the Sound in September, remained fully armed and operational (albeit with a reduced complement), while Schlesien, her armament reduced to a few 10.5cm and 8.8cm guns, still occasionally went to sea for cadet training purposes during the second half of 1918. The remainder all joined the older battleships on harbour service in a disarmed state, their guns sent for land use.

The 28cm guns were installed in railway mountings, while twenty-eight of the 17cm guns went to four four-gun batteries for the coastal defence of Flanders, another thirty being used as railway-deployed field guns (being too heavy for horse or tractor towage); after the war, two three-gun batteries of 17cm guns were deployed for the defence of Heligoland and Kiel. The ex-Braunschweig/Deutschland guns joined a large number of ex-naval heavy guns that had been deployed ashore since the outbreak of war – some from long-disarmed ships, some from vessels paid off during the early years of the war, some intended for uncompleted vessels and some from spares for all three categories.7

As the II. Sqn left the High Seas Fleet, its place was taken by a new IV. Sqn, established on 1 December 1916 from ships previously belonging to the III. Sqn, and comprising four Kaiser class vessels (excluding the fleet flagship Friedrich der Große). The III. Sqn henceforth comprised the Königs, plus Bayern, which was finally fully operational. She was joined in the fleet by her sister Baden early in 1917, which, once fully worked-up, replaced Friedrich der Große as fleet flagship on 14 March. Friedrich der Große then joined her sisters in the IV. Sqn, relieving Kaiser as its flagship. Baden was the penultimate big ship to join the fleet, the last being Hindenburg, which joined the I. SG in November, becoming its flagship on the 23rd.

The Third Battle of Heligoland Bight

On 17 November 1917, the British launched a raid on a group of German minesweepers clearing a field laid in the Heligoland Bight across the swept channels that were used by German submarines bound for the open sea. Part of the British strategy had been to force minesweepers to operate far out into the North Sea, where they were vulnerable to attack, and if they were prevented from carrying out their sweeping activities, this would degrade the submarines’ ability to operate. Also, as the exposed position of the minesweepers meant that they needed close support from cruisers (with distant support from battleships), harassing them also presented an opportunity to draw out and destroy significant surface units. On this occasion, the II. SG (Königsberg, Pillau, Frankfurt and Nürnberg) was in attendance, presenting a useful target. The British force comprised the 1st CS (large light cruisers Courageous and Glorious), the 1st LCS (four ‘C’/Arethusa class), the 6th LCS (four ‘C’ class), and ten destroyers.

Kaiserin, shown from above, a belated participant in the third battle of Heligoland Bight on 17 November 1917. (Author’s collection)

The action began at 07.37, some 65nm west of Sylt, when Courageous opened fire. The II. SG and its torpedo boats were successful in interposing itself between the British and the minesweepers, allowing all but one of them to escape. The II. SG then retreated, under fire from the British force, joined around 10.00 by Repulse, detached from the 1st BCS, which scored a hit on Königsberg, causing a fire. As the Germans reached their own minefields, the action was joined by Kaiser and Kaiserin, a 30.5cm shell from one of which struck the light cruiser Caledon, albeit causing little damage. Calypso was more seriously damaged by a 15cm shell which wrecked her bridge and killed everyone on it, including her captain.

THE BLACK SEA 1916–17

On 9 January 1916, while returning from a protective operation for the Zonguldak coal run, Goeben/Yavuz encountered the new Russian battleship Imperatritsa Ekaterina Velikaya and fought a short action. The Turco-German ship was soon outranged by the Russian, which fired ninety-six rounds without, however, causing anything more than splinter damage.

Goeben/Yavuz and Breslau/Midilli were employed to carry men and equipment to Trebizond on 6 February and from the end of June carried out offshore operations in support of Turkish forces. On 3 July, they sailed for the Caucasus to attack Russian troop transports, and on the following day Goeben/Yavuz bombarded Tuapse harbour, sinking two ships. On the 6th both ships avoided the Russian battleships Imperatritsa Ekaterina Velikaya and Imperatritsa Mariya on their way back to the Bosphorus by sailing close to the Bulgarian coastline. While lying at Constantinople on 9 July, Goeben/Yavuz was the target for a long-distance bombing raid by a Handley Page O/100 heavy bomber; while this reached the city and dropped a number of bombs, the ship herself was not hit.

Goeben/Yavuz spent much of 1917 immobile owing to a shortage of fuel. In May a cofferdam was used to start repairs to a damaged propeller shaft, which completed in August. During July, work began on of the installation of the ‘bearing-indicator’ fire-control system, after which August and September were occupied by further repairs, maintenance and training. Installation of the fire control system was finished during October/November, with trials carried out during December.

BALTIC 1917–18

Operation ‘Albion’

As already noted, after the torpedo and mine casualties of the winter of 1915/16, there was little activity by larger warships in the Baltic theatre, although smaller vessels remained active – and suffered losses from the same causes. Ashore, there was an essential stalemate, but in March 1917 the ‘March Revolution’ in Russia ended the monarchy and although the Provisional Government continued the war, pressure began from the far left for an end to hostilities. Then, in July, the failure of the Kerensky Offensive opened the whole front to a German advance.

Against this background, Operation ‘Albion’ was launched in September 1917 to seize the West Estonian Archipelago that closed off the Gulf of Riga from the Baltic.8 The aim was both to free German forces and trade from the threat of Russian ships and submarines based there and to threaten St Petersburg, with a view to encouraging the Russians to seek an armistice.

German land forces – numbering some 23,000 men, carried from Libau by nineteen ships – were supported by a large naval force under the command of FO I. Sqn., flying his flag in Moltke, a veteran of the 1915 Riga campaign. Under him were the III. Sqn (König, Bayern, Großer Kurfürst, Kronprinz and Markgraf), the IV. Sqn. (Friedrich der Große, König Albert, Kaiserin, Prinzregent Luitpold and Kaiser), the II. and IV. SGs (Königsberg, Karlsruhe, Nürnberg, Frankfurt, Danzig, Kolberg, Straßburg, Augsburg, Blitz and Nautilus), the II., VI., VIII. and X torpedo boat Flotillas (forty-three boats with Emden as leader) and thirteen submarines, plus minesweepers and other supporting vessels. In opposition, the Russian Navy could only deploy the battleships Slava and Grazhdanin (ex-Tsesarevich), the cruisers Bayan, Admiral Makarov and Diana, the gunboats Khrabryi, Groziashchii and Khivinetz, and three divisions of destroyers, led by Novik, torpedo boats, plus other subsidiary vessels.

Although the German-based ships left Kiel on 24 September, weather prevented operations until early October, when aerial bombardment commenced, together with the sweeping of mines in the Irben Strait, which almost immediately resulted in the mining and sinking of T54 and M31, with damage to M75, T85 and Cladow. Finally, on 10 October the III. and IV. Sqns departed Putzig Bay, near Danzig, the naval forces rendezvousing the following day. Minesweeping had not proceeded as planned, while a navigational error meant that when the battleships began planned shore bombardments in support of the German landings (Bayern against the battery at Cape Toffri, the rest of III. Sqn against the battery at Ninnast [Ninase] and IV. Sqn. against battery at Cape Hundsort [Tagamõisa]) they were operating in unswept waters.

Early on the morning of the 11th, Bayern opened fire first, followed by Kaiser, Prinzregent Luitpold and Kaiserin. The Hundsort battery’s reply was aimed at Moltke, its 6in [152mm] shells falling only 100 metres short of her, the second salvo over, and the third 50 metres off her bow. Moltke then added her guns to the bombardment, while shortening the range to just 8000 metres as the landing got underway. In the meantime, the III. Sqn had taken the batteries at Cape Toffri and Ninnast under fire, the latter at a range of 4600 metres, allowing secondary batteries to be used. Großer Kurfürst had carried out her part in the bombardment in spite of having been mined forward on the starboard side shortly before, damage being limited to 280t of water in the double bottom, wing passage and bunkers and adding 10cm to her draught forward.

While firing against the 12cm battery at Cape Toffri, Bayern was also mined, suffering significantly more damage, with the bow and forward torpedo broadside torpedo flat flooded, 1000t of water aboard and seven dead; it is likely that damage was exacerbated by the explosion of the twelve air-accumulators in the torpedo flat. The ship continued to undertake her bombardment, expending twenty-four 38cm and seventy 15cm rounds, at ranges varying from 9300 to 10,200 metres, with Emden also adding her fire while the German landing-forces got into position. In parallel, Friedrich der Große and König Albert undertook a diversionary bombardment to the east of the Sworbe Peninsula. Having completed their duties, the big ships came together that evening at Tagga Bay, between the now-neutralised Ninnast and Hundsort batteries.

Russian naval responses had now begun, Admiral Makarov, Groziashchii, Novik and five other destroyers engaging German torpedo boats that afternoon, while on the 12th intelligence reports of submarines being deployed led to the III. Sqn, except for Markgraf, being sent back to Putzig Bay that evening. From here the damaged Großer Kurfürst and Bayern could proceed to Kiel and beyond for repairs. Großer Kurfürst reached Wilhelmshaven on the 18th; she re-joined the fleet on 1 December.

However, while Bayern was initially able to proceed with her squadron-mates at 11kts, strain on her bulkheads resulted in progressive reductions in speed, until she came to a stop around 20.00 while the bulkheads were shored up. It having been decided that the risk of proceeding further was too great, Bayern returned towards Tagga Bay, escorted by Kronprinz and three torpedo boats, supplemented by further torpedo boats sent out from Tagga Bay. The battleship continued to experience difficulties, stopping again for a number of hours, and finally struggled into Tagga Bay the middle of the next morning for temporary repairs. The ship eventually arrived back at Kiel on the 31st, and was under repair until 27 December. The IV Sqn. remained at Tagga Bay, with König and Kronprinz due to return on the 15th.

On the 13th, further actions took place between Russian destroyers, later joined by Khivinetz, and German light vessels, supported by Emden. The following day, the latter and Kaiser provided fire support for operations to secure the Kassar Wiek, the stretch of water between the islands of Dagö (Hiiumaa) and Ösel, the battleship engaging the Russian destroyers Pobiedtityel, Zabiyaka, Grom and Konstantin at long range. Grom received a shell that passed through her engine room without exploding.

These destroyers subsequently engaged the German light forces penetrating the Kassar Wiek, ships on both sides being damaged, before Khrabryi and Khivinetz joined the action, the former taking Grom, which had been badly damaged by V100, in tow. The tow was subsequently dropped, Grom’s hulk being then captured by the Germans and towed further before foundering in shallow water. Grazhdanin and Admiral Makarov joined the fray late in the afternoon, but the range was too great and fire ceased at nightfall.

The following morning, Friedrich der Große, König Albert and Kaiserin departed Tagga Bay to undertake bombardment duties off the Sworbe Peninsula – Friedrich der Große against ground forces, König Albert and Kaiserin against the battery on Zerel, which mounted four 30.5cm guns, with excellent arcs of fire. In the event, Friedrich der Große joined her sisters in action against the battery, which managed to straddle Kaiserin with its fourth salvo.

The IV. Sqn. returned to their bombardment positions off the Sworbe Peninsula the next morning, but did not open fire until the afternoon, while the III. Sqn supported the minesweepers at work in the Irben Straits. That evening, König Albert and Kaiserin were detached to Putzig Bay to coal whilst Friedrich der Große remained to the west of Sworbe. In parallel, Grazhdanin and destroyers were sent to the area, the Russian battleship escaping a number of attempted attacks by German submarines en route.

König and Kronprinz had now returned to theatre and on the 16th narrowly avoided being torpedoed by HMS/M C27 while en route to face the Russian naval force approaching Moon Sound. Since disembarkation at Tagga Bay was now largely complete, Markgraf was ordered to leave the bay and join her sisters. The next morning, however, before Markgraf could join, Grazhdanin, Slava, Bayan and supporting destroyers launched an attack on the German minesweepers, the Russian battleships and the five 10in [254mm] guns of the Woi shore battery straddling but not hitting the minesweeping force. Unfortunately, a fault developed in Slava’s fore turret during this phase of the operation, and thus she was reduced to a single pair of 12in [305mm] guns when König and Kronprinz appeared on the scene.

On the other hand, the Russian guns (although significantly older than those in the German ships) outranged their German counterparts by 1600m – a legacy of the German pre-war doctrine of short-range fighting. The big battleships’ ability to manoeuvre was also constrained by the swept channel. König having narrowly escaped being hit, they were forced to withdraw in the face of their antiquated opponents, which were able to resume their assault on the minesweepers, joined again by shore batteries.

The German battleships resumed action two hours later at a range of 16,000m or more, König taking on Slava at 10.13 and Kronprinz Grazhdanin four minutes later; Bayan was for the time being ignored. This time, Slava was hit by König’s third salvo, two shells striking below the waterline on the port side, abreast the fore turret, and another hitting the superstructure abreast the forward funnel. This caused 1130 tons of water to enter the ship, causing an 8° degree list, reduced by half through counter-flooding. Two more shells struck the battery deck at 10.24, causing fires that were, however, soon put out, but another two hits at 10.39 were again below the waterline, adding to the flooding and resulting in the after turret also being put out of action through water penetration of its magazines.

Grazhdanin was more fortunate, receiving only two hits, one of which caused a fire that was quickly extinguished, the other of which damaged two generators and several steam pipes. Bayan was belatedly taken under fire by König, and at 10.36 was hit a shell that penetrated both the upper and the battery decks and exploded deep inside the ship, where it caused a fire that was only put out the next day. The German battleships ceased fire at 10.40, the Russians having begun to withdraw towards the Moon Sound dredged channel ten minutes earlier. Unfortunately, Slava now drew too much water to pass, and had to be scuttled, with the intention of also blocking the dredged channel against the Germans. However, she ran aground before being properly positioned, her aft magazines being detonated in an attempt to sink her – an act which, although visible 25 kilometres away, seemingly did little more than blow the roof off the turret. Slava was thus torpedoed by the destroyer Turkmenets Stavropolskii, after which she settled on the bottom in shallow water, burning until the following day; the wreck was broken up in 1935.

The wreck of the Russian battleship Slava, scuttled in Moon Sound on 17 May 1917, following damage in action with König. The aft magazine was detonated as part of the scuttling, the missing roof of the turret being visible in this aerial view. (BA BA 102-03376)

No attempt was made to pursue the remaining Russian ships, since they no longer posed a threat to the minesweepers, the German forces continuing their advance, the König successfully engaging the Werder and Woi shore batteries. The submarine threat remained, both an imagined periscope-sighting and a real – but abortive – attack by HMS/M C26 soon after 12.00.

Earlier in the day, at 09.25, Kaiser had opened the landing on Dagö with a preliminary bombardment of the landing ground at Serro and by the evening good progress had been made throughout the theatre. Consideration was also being given to cutting off the Russian naval forces at the northern end of the Moon Sound, but the decision had already been made to withdraw them into the Gulf of Finland, with the remaining islands evacuated, although Dago was to hold out for as long as possible. The withdrawal took place on the evening of the 19th,

As the campaign wound up, Kaiserin and König Albert were released on the 19th to return to the North Sea, although Markgraf undertook a bombardment of the island of Kyno on the 21st and Hainasch on the 22nd – in both cases using only her secondary guns. She was left temporarily as the last battleship in theatre on the 26th, when König and Kronprinz left for the North Sea, although both touched ground soon after departing, thus requiring dockyard attention once they reached Germany.

Ostfriesland and Thüringen were due to arrive in theatre on the 30th, and thus Markgraf began her voyage home on the 29th. However, soon after departure she struck two mines on her starboard beam; 260t of water was taken aboard, but there were no casualties. The incident nevertheless emphasised the hazards of operating in the area, and accordingly it was decided to withdraw the newly-arrived battleships and the existing cruisers. Moltke, Ostfriesland and Thüringen thus steamed into Putzig Bay on 3 November, the Special Unit established for the Riga operation being dissolved the same day.

The Finnish Expedition

In November 1917, the Russian Provisional Government was overthrown by the Bolsheviks (the ‘October Revolution’), the new regime being determined to take the country out of the war, an armistice being declared on 15 December 1917 and negotiations opened at Brest-Litovsk. In the midst of this, Finland declared independence in December 1917, which was followed by the outbreak of civil war the following month between ‘Red’ and ‘White’ factions. During February 1918, the Swedish armoured ships Thor, Sverige and Oscar II were deployed, with troops, to support the Swedophone, but Finnish (and thus hitherto Russian-ruled), Åland islanders. German intervention followed, with the dispatch of a naval force comprising Westfalen and Rheinland (and later Posen), plus light cruisers, minesweepers (with Beowulf as flagship of the Minesweeping Unit Baltic) and supporting vessels to the eastern Baltic on 28 February. It left Danzig on 1 March and arrived to land troops on the Åland islands on the 5th. Troops of the Baltic Sea Division were then landed at Hangö, to advance towards Helsinki, on 3 April, the city being taken on 12 April. Beowulf was henceforth based at Helsinki on a number of occasions, both in her role as minesweeper flagship, and later as flagship of SNO Baltic.

The three Nassaus had based themselves at Eckerö in the Åland Islands to guard against Russian naval intervention, but since the Russian fleet had withdrawn to Kronstadt, in accordance with the provision of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that had been agreed on 3 March, there was no longer a need for them to remain. Thus, on 11 April, Rheinland sailed for Danzig, via Helsinki; unfortunately, she ran into fog and ran aground on Lagskär Island around dawn while steaming at 15kt. Three boiler rooms were flooded, with the loss of two lives. Initial attempts at refloating on 18–20 April were unsuccessful, and the crew was taken off, being redeployed to reactivate Schlesien as a cadet training ship (cf. p 129).

A 100t-capacity floating crane (the ex-armoured vessel Viper) arrived from Danzig on 8 May, and began the removal of Rheinland’s main guns, together with some of her turret armour. Armour plates were also removed from the bow and other parts of the side protection, ammunition, coal and stores also being unshipped. Some 6400t of material was removed, while the breaches in the hull were sealed with concrete and coffer dams. The last of ten lifting pontoons, constructed at the AG Weser yard, arrived on 16 June and between 7 and 9 July the battleship was finally brought afloat. Rheinland was then towed to Mariehamn back in the Åland Islands for temporary repairs, which lasted until 24 July, when a pair of tugs towed her towards Kiel; she arrived three days later. Given the magnitude of the damage and the ship’s relative obsolescence, no attempt at substantive repairs were made, the damaged boiler rooms being left with holes filled with cement, but still leaking and requiring constant pumping. The ship thus paid off on 4 October and was reduced to an accommodation ship at Kiel.

Her sister Westfalen had been withdrawn from the High Seas Fleet on 1 September, and reduced to the role of gunnery training ship. This followed a period of chronic boiler problems, and meant that by the autumn of 1918, the German fleet’s dreadnought battleship strength was back to where it had been in early 1915 – in contrast to the Grand Fleet’s addition of ten such ships since then.

THE AEGEAN AND BLACK SEA 1918

During 1916, Turgut Reis was re-gunned with weapons removed from her German sisters, the aft turret receiving 35-calibre weapons, as fitted in the midships turret, leaving forward one as the odd one out with 40-calibre guns; she was then laid up at the Haliç. In September 1917 it had been formally agreed between Germany and Turkey that at the end of the war, Germany would not only formally sell the ex-Goeben and ex-Breslau to Turkey, but also add a dozen destroyers and submarines. On 15 December 1917, the end of hostilities seemed to get closer as the armistice between Russia and the Central Powers brought fighting in the Black Sea to an end. It thus released the Ottoman Navy to carry out operations to the west for the first time.

Beowulf was the last operational Siegfried, as flagship of Baltic minesweepers in 1918. Here she is shown as Ems guardship during the winter of 1915/16. (BA 134-C0084)

Thus, on the morning of 20 January 1918, Goeben/Yavuz and Breslau/Midilli sailed out of the Dardanelles to carry out a raid on the British blockading force at their bases off the island of Imbros, and at Mudros, on the island of Lemnos. However, not long after their departure, Goeben/Yavuz struck a mine, in spite of the force’s possession of a captured British sketch-map of the minefields in the area. However, damage was minor, and the ships pushed on, finding the Aliki anchorage empty, but bombarding the radio station at Kephalo en route to the anchorage at Kusu Bay.

There, they first sighted the patrolling destroyer Lizard and then the 14in [356mm]-gunned monitor Raglan,9 the only big-gun ship present, the battleship Agamemnon being at Mudros and her sister Lord Nelson having gone to Salonika four days earlier. Lizard’s attempts at launching a torpedo attack were repulsed, while Raglan failed to hit with her initial salvoes; likewise the 9.2in [234mm] monitor M28 was unsuccessful. A shell from Breslau/Midilli wrecked Raglan’s fire control, while further hits from the cruiser penetrated the engine room. A 28cm shell from Goeben/Yavuz then hit the monitor’s barbette, causing an propellant fire; Raglan then took more hits, being eventually sunk by the explosion of her 12pdr [76mm] magazine. M28 was stricken with an ammunition and oil fire after a hit amidships from Breslau/Midilli, blowing up and sinking at 07.27, twelve minutes after Raglan.

The Turco-German ships then sailed to attack Mudros, under ineffectual attack by British aircraft. However, they soon found themselves in a minefield, Breslau/Midilli exploding a mine with her starboard screw at 07.45, leaving her immobile. While attempting to pass a tow, Goeben/Yavuz struck a mine on the port side amidships, the latter causing sufficient flooding to cause a list. Breslau/Midilli subsequently struck four more mines from 08.00, and sank at 08.07. Goeben/Yavuz managed to extract herself from this minefield, but struck yet another – on the starboard side – at 08.48 close to the location where she had been mined on the outward voyage. Still under air attack, but escorted by four Turkish destroyers, she managed to reach the Dardanelles Narrows where, however, she ran aground off Nagara Point at 10.30, following the mistaken identification of a marker-buoy. Goeben/Yavuz’s forward third was aground, and an attempt by Turgut Reis, withdrawn from reserve for the specific purpose of acting as a tug, to tow her off was unsuccessful.

With the ship immobilised, air attacks began at dawn on the 21st, but ongoing fog contributed to a lack of hits. However, on the next day a DH4 aircraft struck Goeben/Yavuz with a bomb on the after funnel, making a 3m hole, while a hit on a tug alongside caused damage to the bridge. By this time the destroyers Samsun and Mauvent-i Milliye were standing by the stricken ship, with the destroyers Nümune-i Hamiyet and Tasoz and the torpedo boat Akhisar providing a screen. On the 23rd, nine air attacks were made, but only one hit was scored, on the port side aft. The British launched an attack by the 9.2in-gunned monitor M17 on the evening of the 24th, firing indirectly from the other side of the Gallipoli peninsular. This did not, however, score any hits, and fire from Turkish batteries forced the monitor’s withdrawal. Poor weather frustrated further air attacks, including a planned torpedo attack by an aircraft from the seaplane carrier Manxman.

The following day, Turgut Reis and the tugs İntibah and Alemdar arrived to make a new attempt at towing Goeben/Yavuz off her sand-bank, with other ships’ washes being used to erode the bank and a dredge employed to remove material from each side of the vessel. An attempt on the morning of the 26th failed to move her, but that afternoon Turgut Reis was lashed to Goeben/Yavuz’s starboard side, with the battleship’s engines run at full power to loosen the sand. Goeben/Yavuz came free at 16.47 and proceeded to Constantinople. The British were not aware of her departure for two days, launching an air attack on her former location on the 27th and on the 28th by the submarine E14, which was lost on her way back. Turgut Reis then returned to lay-up.

Although significantly damaged by the mines, with a number of wing compartments flooded, her main compartments and machinery remained dry, and thus Goeben/Yavuz could still be regarded as operational. Nevertheless, docking remained highly desirable, the opportunity arising as a result of the German advance across Ukraine that followed the withdrawal of Russia from the war, which did not cease even with the signature of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

Goeben/Yavuz in dock at Sevastopol in June 1918, with boards rigged for painting ship. (Author’s collection)

German troops occupied Odessa on 13 March, followed by Nikolayev on the 18th, crossing into the Crimea and entering Sevastopol on 1 May. In anticipation of this, Goeben/Yavuz had sailed towards the port on 30 April, where her crew initially undertook work in connection with the occupation. Preparations were also made for docking the ship for the first time in four years, this being achieved on 7 June. No attempt was made to repair the mine damage in the time available, work being restricted to cleaning and repainting the ship’s bottom. plus some minor repairs.

At its occupation by the Germans, Sevastopol contained much of the Black Sea Fleet, in particular the battleships Borets za svobodu (ex-Panteleimon), Ioann Zlatoust, Evstsafii, Rostislav and Tri Sveatitelia, which were all seized. In addition, the brand-new battleship Volia (ex-Imperator Aleksandr III) returned to Sevastopol late in June. She had spent the previous few weeks at Novorossiysk whence she had been evacuated on 1 May with her sister Svobodnaia Rossiia (ex-Imperatritsa Ekaterina Velikaia), which had been scuttled there on 19 June.

Following considerable debate, it was been decided that Germany should establish a Black Sea squadron, comprising Volia, five destroyer10 and three or four submarines, to aid the Turks in defending the Dardanelles, and perhaps eventually acting in an offensive role.11 There was also a thought to use Ioann Zlatoust and Evstsafii as floating batteries in the Dardanelles, supported by six ex-Russian destroyers. Volia was formally taken over on 1 October and made some brief trial voyages after the 15th, but was handed over to the British on 24 November, having never been formally commissioned or renamed by the Germans.12

Sevastopol in 1918/19, with the Russian battleship Volia in the foreground, which briefly underwent trials under the German flag in October 1918. The three-funnelled vessels behind her are, from the left: a cruiser (either Ochakov or PamiyetMercuriya); Evstafii; and the training ship (ex-auxiliary cruiser) Rion (ex-Smolensk). (Author’s collection)

Goeben/Yavuz was undocked on 14 June, sailed on the 26th in the company of the ex-Russian German destroyer R10 (ex-Zharkiy, seized on 1 May), and proceeded to Novorossiysk, where they were joined by Hamidieh and Berk-i Satvet. Goeben/Yavuz returned to Sevastopol on 1 July, sailing to Odessa on the 7th, and back again to Sevastopol on the 9th. The following day, Hamidieh towed the recovered cruiser Mecidiye (which had been mined off Odessa on 21 March 1915, salved on the 25th and commissioned into the Russian Navy as Prut on 12 February 1916) out of Sevastopol en route back to Constantinople, Goeben/Yavuz following them on the 11th. Between July and October, work on repairing the mine damage was carried on using cofferdams, but this was brought to an end by the Turkish armistice on 1 November. As a consequence, the German crew left the ship the following day, which was then laid up off İzmit on 9 November to await her fate.

THE NORTH SEA 1918

23 April 1918

Following a successful October 1917 raid by Brummer and Bremse on a British Norwegian convoy, and another raid on 12 December, when four German destroyers sank all five merchantmen and one of two destroyer escorts of another convoy, battleships were detached from the Grand Fleet to provide cover for the convoys. Since this provided the opportunity to pick off isolated parts of the British fleet in accordance with the long-standing German strategy, it was planned to launch an attack on a convoy using the I. and II. SGs, supported by the II. TBF, with the main battlefleet standing-by to engage any British capital ships that might attempt to intervene. It was also hoped that a raid in the north by heavy ships would force British vessels currently based in the English Channel to be redeployed further north, to the advantage of German submarines and light vessels in that area.

Yavuz Sultan Selim laid up in Sea of Marmora during 1919–20. (NHHC NH 63469)

The operation was launched at dawn on 23 April 1918, the attack force being followed by the battlefleet, the I., III. and IV. Sqns being supported by the small cruisers of the IV. SG and the I., VI., VII. and IX. TBF. However, at 06.00, soon after departure, Moltke shed her inner starboard propeller while some 60 kilometres south-west of Bergen. Part of the now-racing turbine disintegrated, with fragments damaging a number of components, plus the deck of the main switch-room. Condenser damage immediately flooded the centre engine room, while the starboard engine room began to fill rapidly. Initially capable of 13kts, Moltke was detached to make her way home, but as salt water was also now contaminating the boiler feedwater, her speed had fallen to 4kts by 08.00 and to nothing by 08.45.

The small cruiser Straßburg was detached to stand by the crippled ship, with Oldenburg detailed as a tug to bring her home. At 11.13 the battleship succeeded in attaching herself to Moltke, the tow-convoy being escorted back to German waters by the fleet. During the afternoon, divers succeeded in closing Moltke’s condenser valves, allowing the flooding to be brought under control and the port-outer engine restarted and run at half-speed. However, the tow was maintained in case of a further breakdown, 11kt being attained until the hawser broke at 20.50. The tow was resumed around 22.00 continuing until the fleet was through the minefields around 19.00 on the 25th, Moltke then being cast off as now able to steam at 15kts. Unlucky to the end, an hour later, she was hit by a single torpedo fired by HMS/M E42. Although 1800t of water had entered her hull, Moltke still managed to reach Wilhelmshaven under her own steam, repairs being carried out there between 30 April and 9 September. This was to be the last time that the High Seas Fleet would carry out an operation into the North Sea.

The Final Battle That Never Was

On 13 August, Capelle resigned as State Secretary, and was replaced by Paul Behncke (1866–1937), former FO III. Sqn. Six weeks later came the official realisation by the German high command that the war was now unwinnable and that moves towards an armistice should begin. As part of the preliminaries towards this, the German government agreed on 20 October 1918 to end the submarine campaign against merchantmen. With the new availability of submarines for fleet support – and with the wider aim of maintaining the ‘honour’ of the navy and possibly influencing the peace settlement – the Admiralty (without reference to the government) revived an operational plan originally drawn up in 1916, with the aim of provoking a final battle with the Grand Fleet.13

The concept was that an attack would be made on shipping off the Flanders coast (by a flotilla of torpedo boats supported by the light cruisers Graudenz, Karlsruhe and Nürnberg, from the II. SG)) and in the Thames estuary (by the rest of the II. SG and a half-flotilla of torpedo boats), with the aim of (as per German strategy since the beginning of the war) drawing down elements of the British fleet, which would be decimated by newly-laid minefields and attacks by the enhanced submarine force. The main fleet and I. SG would cover the attacks and engage the British ships drawn out by the operation. By this point the Grand Fleet outnumbered the High Seas Fleet by 35:18 in battleships, 15:5 in battlecruisers/armoured/large cruisers, 36:14 in light cruisers and 146:60 in destroyers/torpedo-boats (not counting the Harwich Force and other detached commands in the North Sea, with eight light cruisers and ninety-nine destroyers), while the British shell and propellant-handling issues that had respectively minimised German damage and magnified British losses at Jutland had been essentially resolved.14 The outcome of any encounter between the High Seas Fleet and the full Grand Fleet is thus difficult to doubt – especially as the British code-breakers had ensured that the Grand Fleet was aware of German plans; however, the view of the German command was that any damage to the Grand Fleet was worth whatever losses incurred by the German fleet, both with a view of peace negotiations and the reputation of the German navy.

The order for the operation was issued on 24 October, with sailing scheduled for the 30th, with the cruiser raids to take place the next morning and any fleet action the following night or the early morning of 1 November. The ships began assembling in Schillig Roads on the 29th, but while passing through the Wilhelmshaven locks, Derfflinger and Von der Tann temporarily lost between 200 and 300 men to desertion. There was also unrest aboard Markgraf, König and Thüringen, which was followed the next morning by members of the latter’s crew refusing to weigh anchor. In light of this, it was initially decided to scale back the operation to just the cruiser raids (with the rest of the I. Sqn in support); the whole operation would soon, however, be cancelled.

Thüringen remained in the hands of mutineers on the 31st, when it was decided to send marines to break the mutiny, covered by the 15cm-armed submarine U135, while the destroyer B97 also stood ready to fire on the rebel battleship. Helgoland was also now in the hands of mutineers, and trained her secondary battery on U135 and accompanying vessels carrying the marines. In the meantime, loyalists aboard Thüringen had seized her aft turret, which they trained on Helgoland until ordered to return to midships by U135. However, before any shots were fired, Thüringen’s crew were prevailed upon the surrender and the mutineers imprisoned ashore, along with mutinous members of the crews of Markgraf, König, Oldenburg and Friedrich der Große.

Had the fleet been kept together at Wilhelmshaven, it is possible that order might have been restored; however, it was dispersed, the I. Sqn going to Brunsbüttel, the I. SG to Cuxhaven and the III. Sqn to Kiel, whose dockyard had already suffered from unrest and strikes. The III. Sqn’s arrival on 1 November was the catalyst for the revolution that spread across Germany and culminated in the abdication of the Emperor on 9 November; between then and the end of November all other German monarchs would also abdicate.

Some vessels remained loyal, for example the Sound guardship Hannover, which ended the war at Swinemünde, returning to Kiel on 14/15 November, in company with the cadet training ship Schlesien, which had sailed from Kiel on the 5th to Flensburg, and then Äro, to escape the unrest. However, the German navy was for the time being finished as an effective combat force.

INTERNMENT

The armistice that ended the First World War came into effect on 11 November. Under paragraph 23:

German surface warships which shall be designated by the Allies and the United States shall be immediately disarmed and thereafter interned in neutral ports or in default of them in allied ports to be designated by the Allies and the United States. They will there remain under the supervision of the Allies and of the United States, only caretakers being left on board. The following warships are designated by the Allies: Six battle cruisers, ten battleships, eight light cruisers (including two mine layers), fifty destroyers of the most modern types.

Königsberg brought delegates to Rosyth to arrange the transfer of interned surface ships on 15 November (Helgoland had previously visited Harwich in connection with the handover of submarines there under paragraph 22). The capital ships to be interned were essentially the newest of each category, excluding the fleet flagship Baden. However, poor intelligence on the part of the Allies meant that the far-from-complete Mackensen (and also the similarly-incomplete small cruiser Wiesbaden [ii]) were included on the original internment list, in spite of the German negotiator having pointed out her state. Although the Allies initially demanded that she be towed if unable to proceed under her own steam, it was eventually decided by the Allies (under German protest) that Baden should be substituted for the large cruiser.

Derfflinger preparing to leave Wilhelmshaven for internment. (Geirr Haar collection)

Norway and Spain having declined to host the interned fleet, it had been directed that they should be laid up at Scapa Flow, guarded by the Grand Fleet. Led by the light cruiser HMS Cardiff, and met by the whole Grand Fleet (including the American 6th BS), the German vessels sailed in line-ahead to the Firth of Forth on the 21st, with Seydlitz in the van, followed by Moltke, Hindenburg, Derfflinger, Von der Tann, Friedrich der Große (flag), König Albert, Kaiser, Kaiserin, Prinzregent Luitpold, Bayern, Kronprinz Wilhelm, Markgraf, Großer Kurfürst, and then HMS Phoebe, leading the light cruisers Karlsruhe, Frankfurt, Emden, Nürnberg, Brummer, Cöln and Bremse; forty-nine torpedo boats followed (a fiftieth, V30, had been mined and sunk en route). Having anchored temporarily in the Forth estuary, the German ships sailed in batches to Scapa Flow.

A Kaiser class battleship deammunitioning in November 1918. (Author’s collection)

Former capital ships on subsidiary duties at the end of the war

Moltke, Hindenburg and Derfflinger steam towards internment, watched by the British airship C*3. (NHHC NH 2598)

Kaiser Wilhelm II, although disarmed in 1916, remained in commission beyond the end of the war as a stationary harbour flagship at Wilhelmshaven, first for the CinC High Seas Fleet, and then for the FO North Sea, before finally paying off in September 1920. Here, she is seen in the second half of 1918 with, at top left, the submarine salvage ship Cyclop, and bottom left the small cruiser Hamburg, acting as the flagship of Senior Officer Submarines. (Author’s collection)

Twenty destroyers moved to the Flow on 23 November, twenty more on the 24th, the I. SG and the remaining destroyers on the 25th, the rest of the vessels being transferred on the 26th (five battleships and four light cruisers) and 27th. The transports Sierra Ventana and Graf Waldersee arrived on 3 December to begin the repatriation of those not required to form the ships’ caretaker crews: 4000 left on the 3rd, 6000 on the 6th and 5000 on the 12th, leaving 4815; subsequently, some 100 were repatriated each month. On the 4th, König, which had been unable to sail with the main body for reasons that are unclear, the light cruiser Dresden (substituting for Wiesbaden) and a destroyer (vice V30) also dropped anchor in the Flow. The final arrival was the fleet flagship Baden (vice Mackensen) on 9 January 1919, which had left Wilhelmshaven on the 7th, escorted by the small cruiser Regensburg, which then repatriated her crew; on arrival, the battleship was inspected by a team from HMS King George V.

Panorama from the south of the German ships interned at Scapa Flow. In the foreground are, from the right, Hindenburg and Derfflinger; behind them are Kaiser, Prinzregent Luitpold, Kaiserin and Karlsruhe (C W Burrows, Scapa with a Camera [1921], p.23)

As regards the remainder of the fleet, the final part of paragraph 23 stated:

All other surface warships (including river craft) are to be concentrated in German naval bases to be designated by the Allies and the United States and are to be completely disarmed and classed under the supervision of the Allies and the United States.

Under this, the Nassaus, Helgolands and remaining seagoing older ships had their guns disabled and were laid up at their home ports to await events.

1. For 1915-18 projects, see F Forstmeier and S Breyer, Deutsche Grösskampfschiffe 1915-1918: Die Entwicklung der Typenfrage im Ersten Weltkrieg (Bonn: Bernard & Graefe, 1970).

2. When Ersatz-Kaiser Wilhelm II was launched and formally named in June 1917, the old Württemberg (i) was still on the Navy list; there were thus two ships of the name on the list between then and November 1919.

3. Jane’s Fighting Ships 1919, p. 515 alleges, under the Bayern class, that ‘Ersatz Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, begun by Howaldt, Kiel, 1915, never got beyond framing stage, and was dismantled’; this is presumably an artefact of erroneous Allied intelligence, which will have been aware that Kaiser Wilhelm der Große was indeed the next battleship due for replacement. On the other hand, there is no reference to this phantom ship in the 1917 or 1918 Admiralty Confidential Books (the latter reprinted as N. Friedman [ed.] German Warships of World War I: The Royal Navy’s Official Guide to the Capital Ships, Cruisers, Destroyers, Submarines and Small Craft, 1914–1918 [London: Greenhill Books, 1992]) on the German Navy.

4. It is interesting to note British intelligence’s confusion over the Mackensens, as manifest in the Admiralty Confidential Books. In October 1917, it was stated that Ersatz-Victoria Louise was to be called Manteuffel, with Ersatz-Freya being Mackensen, with both ships sisters of Hindenburg. A year later, the October 1918 Confidential Book had corrected Mackensen’s Ersatz-identity, but still listed her as ‘believed’ to be a sister of Hindenburg – and completed in September 1918, leading to her internment being demanded under the Armistice (see p 138, below). The remaining large cruisers also remained poorly-understood, since although the names Graf Spee and Prinz Eitel Friedrich were known, they were respectively equated with Ersatz-Freya (the real Ersatz-Freya remaining unknown) and a wholly-fictional Ersatz-Vineta (the next Victoria Louise due for replacement). Also, while Graf Spee’s builder was correctly identified, the name Prinz Eitel Friedrich was associated with the ship building at Wilhelmshaven (actually Ersatz-Friedrich Carl/A). In addition, the two ships were listed as being armed with six 38cm and shown in accordance with Scheme D48 – although noting that it remained ‘possible … that they are merely improved Hindenburgs’.

5. Goldrick, Before Jutland, pp 53–4.

6. R Greger, ‘German Seaplane and Aircraft Carriers in Both World Wars’, Warship International 1(1964), pp 87–91.

7. For German naval guns ashore, see N Friedman, Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations (Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2011), pp 128–30.

8. For a detailed treatment of this campaign see M B Barrett, Operation Albion: The German Conquest of the Baltic Islands (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2008), with the naval side covered particularly in pp 199–220; see also Staff, Battle of the Baltic Islands 1917.

9. Coincidentally armed with guns ordered for Salamis.

10. Three modern Russian destroyers were taken over on 1 May, one of which had been commissioned under the German flag by the end of the war (R01, ex-Schastlivyy), plus four older vessels.

11. H H Herwig, ‘Admirals versus Generals: the War Aims of Imperial Germany, 1914–1918’, Central European History 5 (1972), pp 229–30.

12. Taken by the British to İzmit, on the Sea of Marmara, she became the White Russian General Alekséev in October 1919, and was evacuated to Bizerte with the rest of the White fleet in November 1920. Interned by the French, negotiations for her return to Russia fell through and she was sold for scrap in 1928; she foundered at her moorings in 1931, but was salved and broken up by 1936, her guns being later sold to Finland for coast defence purposes in 1940, four ending up in German hands.

Of the older ships seized by the Germans, they then had their their engines wrecked by demolition charges at the British evacuation on 25 April 1919. They then were taken over by White Russian forces in June, and some prepared for potential use as towed floating batteries, although only Rostislav was so-employed (in the Sea of Azov; she was subsequently sunk as a blockship off Kerch on 16 November 1920 and partly broken up during 1922–30). The remaining ships fell back into Bolshevik hands in November 1920 and subsequently scrapped; for full details of the ships and their careers, see McLaughlin, Russian & Soviet Battleships.

13. For a convenient summary of the events and their aftermath, see D Woodward, ‘Mutiny at Wilhelmshaven 1918’, History Today 18 (1968), pp.779–85.

14. I McCallum ‘The Riddle of the Shells.’ Warship 2002–3, pp 3–25; Warship 2004, pp 9–20; Warship 2005, pp 9–24.