CHAPTER 7

CONTEMPORARY RELEVANCE OF ETHNO-VETERINARY PRACTICES AND A REVIEW OF ETHNO-VETERINARY MEDICINAL PLANTS OF WESTERN GHATS

M. N. B. NAIR1 and N. PUNNIAMURTHY2

1Trans-disciplinary University, Veterinary Ayurveda Group, School of Health Sciences, 74/2, Jarakabandekaval, Attur Post, Yelahanka, Bangalore, India, E-mail: nair.mnb@frlht.org

2Veterinary University Training and Research Centre, Pillayarpatty, Thanjavur–Trichirapally National Highway (Vallam Post), Near RTO’s Office, Thanjavur – 613403, India, E-mail: thanjavurvutrc@tanuvas.org.in

CONTENTS

7.2The Western Ghats or Sahyadri

ABSTRACT

The Veterinary science in India has a documented history of around 5000 years. The veterinary and animal husbandry practices are mentioned in Rigveda (2000–1400 BC) and Atharvaveda.

India is the world’s largest milk producer. The increase in the advocacy of exotic breed for higher milk production has led to many problems. There is high incidence of disease in cross-breed animals and indiscriminate use of antibiotics and other veterinary medicine in dairy animals leading to high veterinary drug residues in the various animal products. People use milk, meat, eggs and other dairy products as their food. The widespread use of antimicrobials and poor infection control practices in livestock management lead to the antibiotic residue in the milk and other animal products, and encourages spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This could cause health hazards to consumers. By 2050 the death by AMR is estimated to be 10 million. The unique Ethno-veterinary heritage of India, documented, rapidly assessed and subsequently mainstreamed into the livestock management among veterinarians and farmers as the first line of treatment for management of animal health conditions. This could lead reduction of use of antibiotics and associated AMR. Nearly 10% of the native plant species, including those having medicinal properties in the Western Ghats are part of the endangered species list. 281 species from Western Ghats are listed with their specific use for animal health.

7.1INTRODUCTION

Livestock rearing is considered as a supplementary occupation to many farmers and also a source of additional income for those engaged in agricultural operations in India. Decline in the animal husbandry budget for veterinary services has led to the scanty veterinary services provided by the government to the poor in the rural areas (Anonymous, 2004). Prevention, control and eradication of diseases among domesticated animals are major concern as diseases in animals will lead to economic loses and possible transmission of the causative agents to humans. Veterinary services have a crucial role in controlling highly contagious diseases and zoonotic infections, which have implications for human health as well as that of livestock. Mainstreaming EVP for livestock keeping is essential for reducing the antibiotic use and for sustainable livestock production.

People use milk, meat, eggs and other dairy products as their food. Indiscriminate use of antibiotics and other chemical veterinary medicine in dairy animals cause high veterinary drug residues in the animal products leading to Antimicrobial resistance (Hill and McLaughlin, 2006). Food safety and Standard act 2006 of India, Chapter 4 Item 21 indicates that pesticide, veterinary drug residues, antibiotic residues and microbial counts (1) “No article of food shall contain insecticide or pesticide residues veterinary drug residues, antibiotic residues, solvent residues, pharmacologically active substances and microbial counts in excess of such tolerance limit as may be specified by regulations.” However, there is no effective government regulation to control antibiotic use in human beings and domestic animals in India. The widespread use of antimicrobials and poor infection control practices in livestock management lead to the antibiotic residue in the milk and other animal products, and encourages spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

The projection of deaths by 2050 due to AMR per year will be 10 million compared to other major causes of death (Cancer 8.2 million), (Asia: 4,730,000 every year, Africa: 4150,00 every ear, Europe: 390,000, North America: 319,000, Latin America: 392,00). By 2050, world can expect to lose between 60 and 100 trillion USD due to AMR. 100,000–200,000 tons of antibiotics are used worldwide. US Production is 22.7 million kilograms and 70% of antibiotics dispensed are given to healthy livestock to prevent infections and/or promote growth. This practice is outlawed in EU countries (Md. Nadeem Fairoze 2015 – Presented in the International conference at TDU April 30–May 1st, 2015).

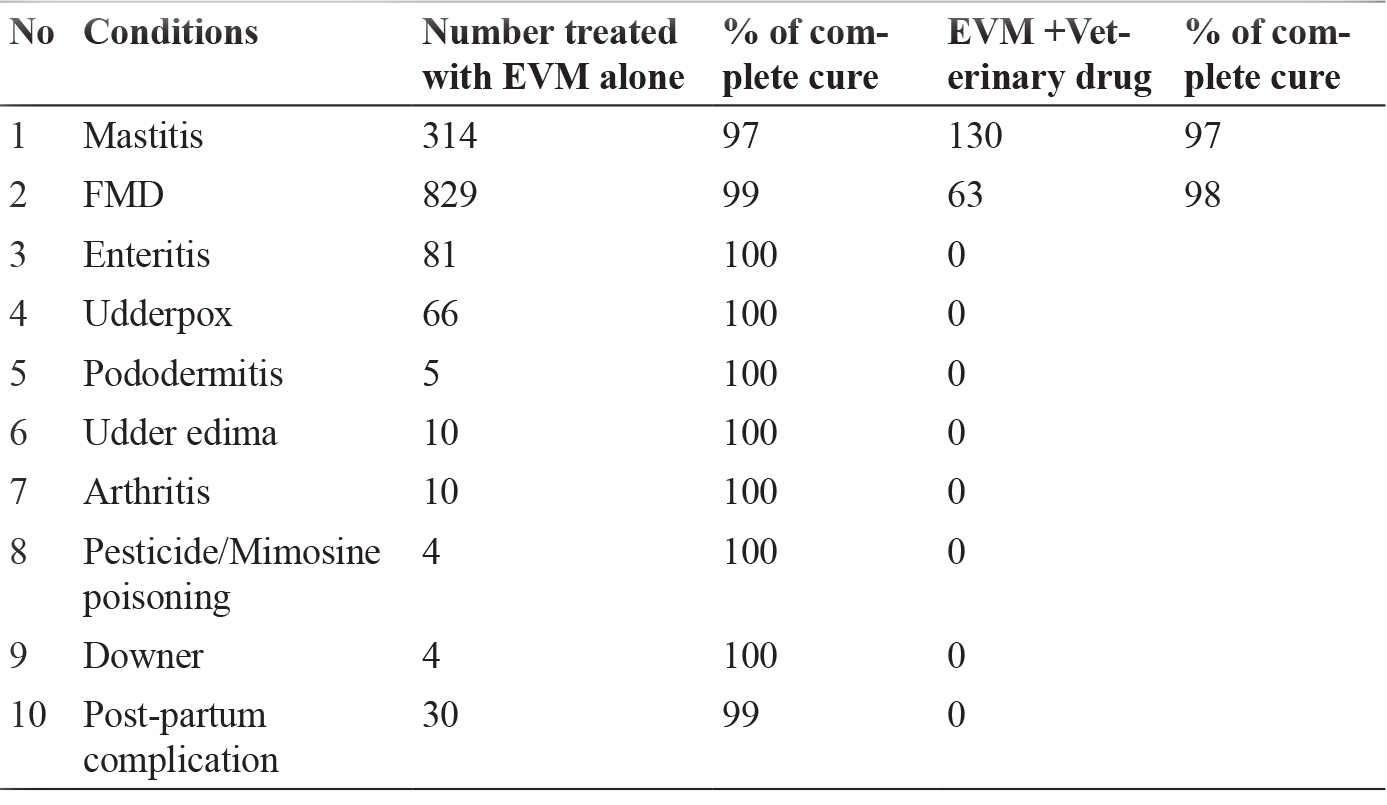

TDU and TANUVAS had documented Ethno-veterinary practices from 24 locations in 10 states, rapidly assessed them and established that 353 out of 460 formulations documented are safe and efficacious. A total of 140 medicinal plants were used in these formulations. The unique Ethno-veterinary heritage of India, assessed subsequently mainstreamed into the livestock management among veterinarians and farmers. The safe and efficacious formulations used as the first line of treatment for management of animal health conditions subsequently leading to the reduction of antibiotics. An observational study indicate 97% efficacy of EVP for mastitis, 99% in Foot and mouth disease, 100% in enteritis, udder pox, pododermitis, udder oedema, arthritis, pesticide/mimosine poisoning and downer (Table 7.1). An intervention impact analysis indicates a trend in reduction of antibiotic residue in the milk after training the farmers and veterinarians to use EVP for 15 clinical conditions in animals in selected areas. The goal of judicious use of antibiotic has to be achieved through creating awareness among the veterinary doctors, dairy cooperatives and people, by training them to use these effective herbal alternatives to antibiotics. The use of antibiotics and other chemical veterinary drugs have in fact been banned for animal health care in many countries and the world is looking for safer herbal alternatives.

TABLE 7.1Efficacy of Herbal Medicine –Field Study

Ethno-veterinary practices were used by humans from ancient times to take care of the health of domesticated, which are recorded in the river valley civilizations. Egyptian had used knowledge of more than 250 medicinal plants and 120 mineral salts (Swarup and Patra, 2005). The veterinary science in India has a documented history of around 5000 years. The veterinary and animal husbandry practices are mentioned in Rigveda (2000–1400 BC) and Atharvaveda. A detailed historical perspective ethno-veterinary practices is available in the publication by Nair and Unnikrishnan (2010).

In India the veterinary medical knowledge can be classified into codified traditions and folk medicine. In the ‘codified’ traditions, the medical knowledge is documented and presented in thousands of medical manuscripts, such as Mrugayurveda and Hastyayurveda. The medical literature from all these traditions is in both classical and regional script and languages. There is no ‘exhaustive’ catalog of the corpus of medical literature available in any of these medical traditions.

The folk traditions are oral and are passed on from one generation to the other by word of mouth. They are dynamic, innovative, and evolving. These oral or folk medical traditions are extremely diverse, since they are rooted in natural resources located in so many different ecosystems and community. Ethno-veterinary practices comprise of belief, knowledge, practices and skills pertaining to health care and management of livestock. They form an integral part of the family and play an important social, religious and economic role. As the ethno-veterinary practices are eco-system and ethnic-community specific, the characteristics, sophistication, and intensity of these practices differ greatly among individuals, societies, and regions. There are local healers and livestock raisers (both settled and nomadic) who are knowledgeable and experienced in traditional veterinary health care and are very popular in their communities. EVP has great potential to address current challenges faced by veterinary medicine as they are safe, efficacious and create no adverse effects in the animals. The Ethno-veterinary traditions can take care of wide range of ailments. However, they are facing the threat of rapid erosion. According to Anthropological Survey of India (ASI), there are 4635 ethnic communities in India. In principle, each of these communities could be having their own oral medical traditions for human and animals that have been evolving across the time and space. The urgent revival of these traditional veterinary practices is a high priority in the light of the constraints of modern medicine and the benefits of these practices.

An annotated bibliography on the Indian ethno-veterinary research was published by Ramdas and Ghtoge (2004). The Indian Council of Agricultural Research in the year 2000 collected 595 veterinary traditions from different sources and recorded (Swarup and Patra, 2005). About 48 of them were recommended for scientific validation and some have shown therapeutic and ameliorative potential. In another work on ‘identification and evaluation of medicinal plants for control of parasitic diseases in livestock,’ 158 plants have been cataloged and 50 have been evaluated for anti-parasitic activity (Anonymous, 2004). Ethno-veterinary practices on eye diseases, helminthiasis, repeat breeding, corneal opacity, simple anorexia, lacerated wounds, mastitis and the common health problems in cattle and their management were described by Nair (2005) and Nair and Unnikrishnan (2010).

Ethno-veterinary research should put more emphasis on first, documentation of the knowledge in new unexploited areas, and secondly, on learning procedures and methods as used in tradition knowledge. Studies on Pharmacognosy in ethno-veterinary medicine seem to be very limited. The reason for this is that since many pharmacognosy studies have been done on plants used in human medicine and several medicinal plants used for humans and animals are often overlap, the pharmacognosy of many ethno-veterinary plants does not need to be repeated for animals. For validation of the ethno-veterinary medicine all factors including the prevailing culture and belief should be considered (Mathias, 2006).

7.2THE WESTERN GHATS OR SAHYADRI

The Western Ghats or Sahyadri are a unique mountain range that runs almost parallel to the western coast of the India. Western Ghats are amongst the 34 biodiversity hot-spots identified in the world. The Western Ghats are region of immense global importance for the conservation of biological diversity and also contain areas of high geological, cultural and esthetic values. Besides the Western Ghats contains numerous medicinal plants, it also houses large number of economically important genetic resources of the wild relatives of grains, fruits and spices plants (Conservation International: Biodiversity Hotspots – Western Ghats and Sri Lanka (March, 2011) accessed http://www.arkive.org/eco-regions/western-ghats/image-H436-10/06/2015.Western Ghats directly and indirectly supports the livelihoods of over 200 million people through ecosystem services. In addition to rich biodiversity, the Western Ghats is home to diverse social, religious, and linguistic groups.

Nearly 10% of the native plant species, including those having medicinal properties, in the Western Ghats are part of the endangered species list. As the part of protection of rich wildlife 13 national parks two biosphere reserves and many wildlife sanctuaries are established across the mountain range. The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve is the largest protected area in the Western Ghats. Spread across three different states this reserve covers an area of around 5500 sq.km. The most important national parks in the Western Ghats are Bandipur National Park, Karnataka, Kudremukh National Park, Karnataka, Chandoli National Park, Maharashtra, Eravikulam National Park, Kerala, Grass Hills National Park, Tamilnadu, Karian Shola National Park, Tamilnadu, and Silent Valley National Park, Kerala (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_Ghats).

There are many reports on the use of ethnoveterinary plants in Western Ghats (Prasad et al., 2014; Nair, 2005; Nair and Punniamurthy, 2010). Kiruba et al. (2006) enumerated 34 ethnoveterinary plants of Cape Comorin, Tamilnadu.

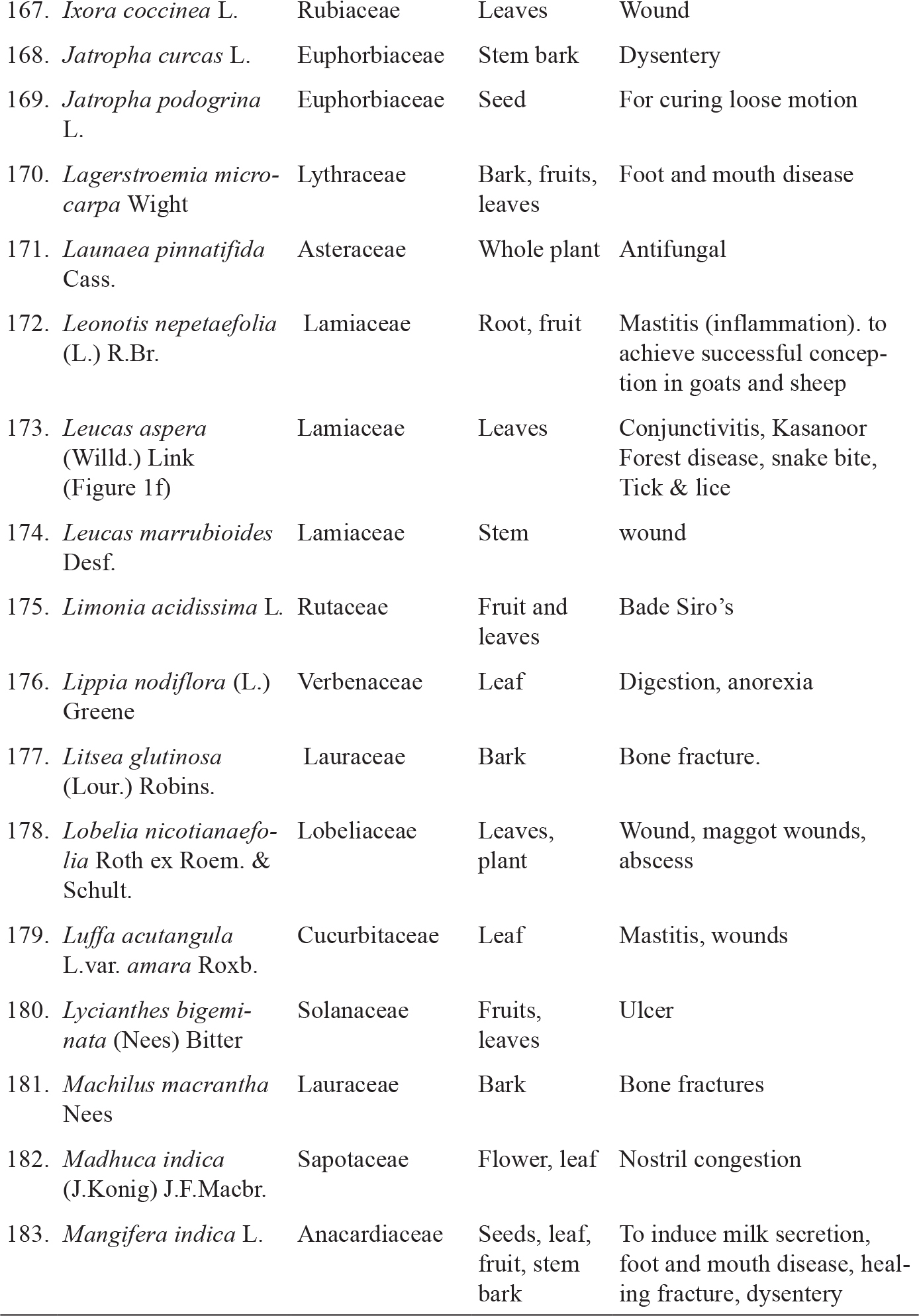

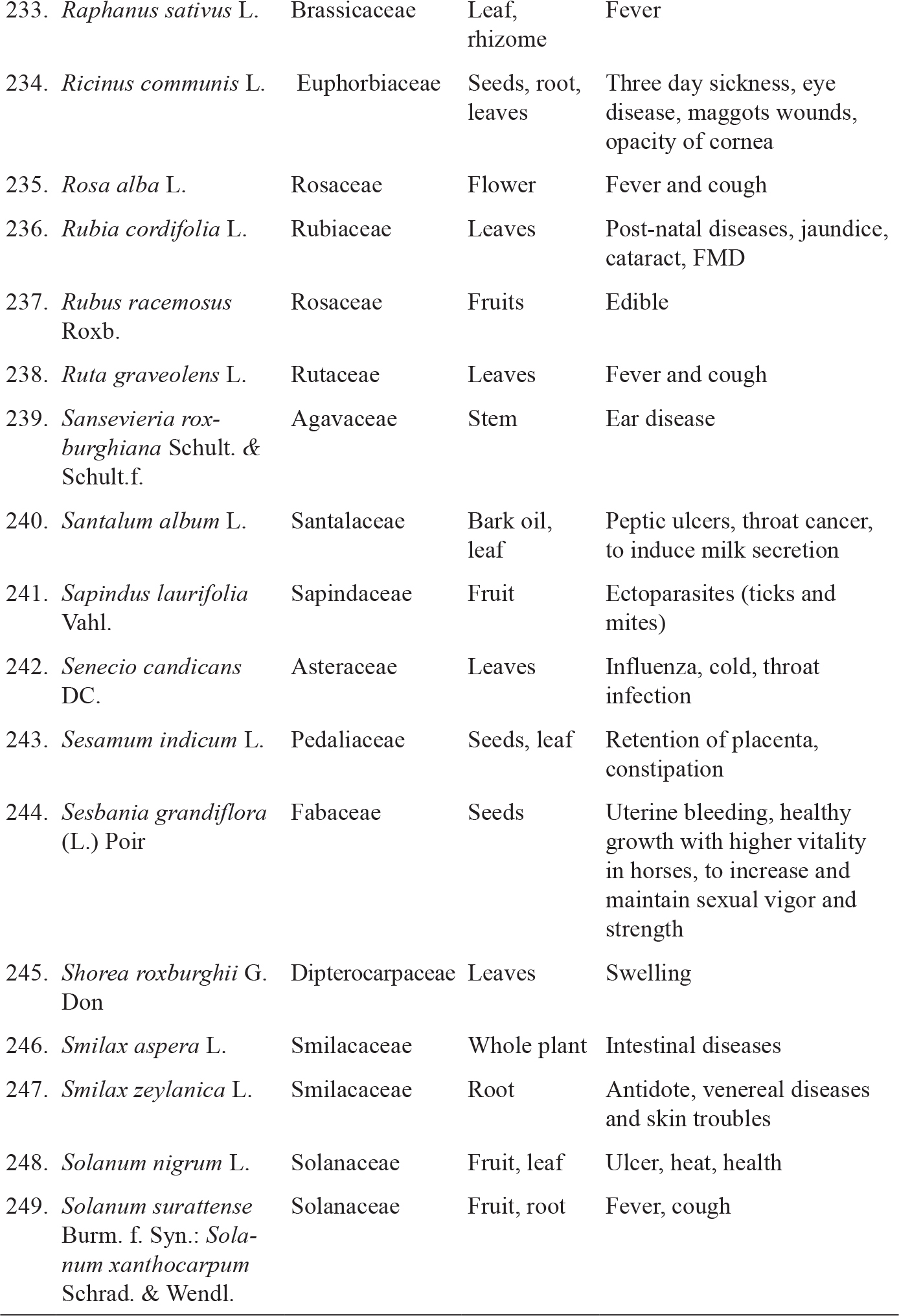

Veterinary wisdom for the Western Ghats was elucidated by Rajagopalan and Harinarayan (2001). Mini and Sivadasan (2007) described the use of 39 species of flowering plants by Kurichya tribe of Wayanad district of Kerala for the treatment of diseases of domestic animals, such as cattle, dogs and poultry. Ashok et al. (2012) reported that 21 plants belonging to 15 families are used for EVP by Dhangar, Laman and Vanjaris tribes from Karanji Ghat in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra. Shimoga district has 52 species belonging to 38 families which are used for veterinary healthcare (Rajkumar and Shivanna, 2012). There are 281 species of Ethno-veterinary medicinal Plants reported from Western Ghats (Table 7.2) (Kiruba et al., 2006; Kholkunte, 2008; Deokule and Mokat, 2004; Ashok et al., 2012; Alagesaboopathi, 2015; Harsha et al., 2005; Rajkumar and Shivanna, 2012; Raveesha and Sudhama 2015; Nair and Unnikrishnan 2010; Renjini et al., 2015; Prasad et al. 2014). 198 species are reported to be used for ethno-veterinary purpose without mentioning the specific disease conditions for which they are used (Somkuwar et al., 2015). An Ethno-veterinary survey was carried out on the indigenous knowledge of tribes and folk medicine practitioners of Mallenahalli village, Chikmagalur Taluk, Karnataka. The study indicates that 52 medicinal plant species belonging to 32 families have been used to treat against anthrax, foot and mouth diseases, bloat, conjunctivitis, dysentery, fractures, snake bite, rot tail, Kasanoor forest disease (Raveesha and Sudhama, 2015).

Ethno-veterinary medicinal uses of plants from Agasthiamalai Biosphere Reserve (KMTR), Tirunelveli District, Tamilnadu was given by Kalidass et al. (2009). Clinical trials using ferns Actiniopteris radiata, Acrostichum aureum and Hemionitis arifolia for anthelmintic property on naturally infected sheep against Haemonchus contortus are proved to be effective (Rajesh et al., 2015). 25 formulations from 39 plant species belonging to 30 families used to treat 21 diseases conditions of domestic animals are reported from Uttar Kannada district of Western Ghats. The method of preparation, dose of each plant along with its botanical name, family and local names are reported (Harsha et al., 2005). The petroleum ether extract of leaves of Tetrastigma leucostaphylum (Dennst.) Alston showed acaricidal activity against Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) annulatus (Krishna et al., 2014). The acaricidal properties of Acorus calamus, Aloe vera and Allium sativum) have also been reported (Prathipa et al., 2014). Herbal medicines create suitable environment for the natural wound healing process (Gopalakrishnan, 2013).

TABLE 7.2Ethnoveterimedicinal Plants of Western Ghats, Parts Used and Ethnoveterinary Uses

7.3DISCUSSION

Presently traditional veterinary health techniques and practices, traditional management as well as herbal and holistic medicines are increasingly being accepted in western societies (Khan et al., 2006; Dangol et al., 2006). The past prejudice on the Ethnoveterinary medicine seems to be reducing and scientific evaluation and validation of the ethnoveterinary preparations has been initiated by considerable number of researchers (Garforth, 2006; Mathias, 2006). It is now realized that a complementary medical approach is crucial and necessary to boost livestock production at community level. Because of their holistic nature, traditional remedies offer efficacy combined with safety more often than single cosmopolitan/conventional drugs. There are no harmful effects in most cases with the use of traditional medicine. Many plant based drugs are being tested for the control of the insects, worms and microorganisms affecting the domesticated animals (Butter et al., 2000; Rios and Recio, 2005; Max et al., 2006). Southeast Asia has the rich biological, cultural diversity and the knowledge to use the traditional medicine. It also has excellent infrastructure and expertise to develop human and animal health. There is an upsurge interest in the herbal/alternate medicine all over the world because widespread use of antimicrobials and other chemical drugs in livestock management led to the antibiotic and chemical drug residues in the milk and other animal products, and encourages spread of AMR. It is reported that Western Ghats houses several species used for animal health and need more documentation for further understanding the species now available. It is essential to conserve them otherwise several of the available species which are endangered now will extinct fast.

KEYWORDS

•Dairy and Other Animal Products

•Ethno-Veterinary Practices

•Medicinal Plants

•Western Ghats

REFERENCES

Alagesaboopathi, C. (2015). Medicinal plants used in the treatment of livestock diseases in Salem district, Tamilnadu, India. J. Pharmaceu. Res., 7, 829–836.

Anonymous (2004). Identification and evaluation of medicinal plants for control of parasitic diseases of livestock. Technical Report. CIRG. Makhdoom (Madhura).

Ashok, S.P., Sonawane, B.N. & Diwakar Reddy, P.G. (2012). Traditional Ethno-veterinary practices in Karanji Ghat areas of Pathardi Tasil in Ahmednagar District (MS) India. Intern. J. Plants, Animals and Environ. Sci., 2, 64–69.

Butter, N.L., Dawson J.M., Wakelin, D. & Buttery, J. (2000). Effect of dietary tannins and protein concentration on the nematodes infection (Trichostrongylus colubriformis) in Lambs. J. Agric. Sci., 134, 89–99.

Dangol, D.R., Teeling, C. & Grout, B.W.W. (2006). Ethnoveterinary medicine and traditional healers of Taru community in Citwan Terai of Nepal. Harvesting Knowledge, Pharming Opportunities. Ethnoveterinary Medicine conference. British Society of Animal Science, Writtle College, Chelmsford, UK.

Deokule, S.S. & Mokat D.N. (2004). Plants used as veterinary medicine in Ratnagiri District of Maharashtra. Ethnobotany 16, 131–135.

Garforth, C.J. (2006). Local knowledge as a resource in the developing Livestock systems. Harvesting Knowledge, Pharming Opportunities. Ethnoveterinary Medicine conference, British Society Animal Science, Writtle College, Chelmsford, UK.

Gopalakrishnan, S. (2013). Wound healing activity studies on some medicinal plants of Western Ghats of South India. J. Bioanal. Biomed., 5(4), http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/1948–593X.S1.011.

Harsha, V.H., Shripathi, V. & Hegde, G.R. (2005). Ethno-veterinary practices in Uttar Kannada district of Karnataka. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 4, 253–258.

Hill, A.L. & McLaughlin, K. (2006). Antibacterial synergy between essential oils and its effect on antibiotic resistance bacteria. Harvesting Knowledge, pharming Opportunities, Ethnoveterinary Medicine conference, British Society Animal Science, Writtle College, Chelmsford, U.K.

Kalidass, C., Muthukumar, K., Mohan, V.R. & Manickam, V.S. (2009). Ethnoveterinary medicinal uses of plants from Agasthiamalai Biosphere Reserve (KMTR), Tirunelveli District, Tamil Nadu, India. My Forest, 45(1), 7–14.

Khan, M.A.S., Akbar, M.A. & Ahmed, T.U. (2006). Efficacy of Neem (Azadirachta indica) and pineapple (Ananas comosus) leaves as herbal dewormer and its effect on milk production of dairy cows under rural condition in Bangladesh. Harvesting Knowledge, Pharming Opportunities Ethnoveterinary Medicine conference, British society of animal Science, Writtle College, Chelmsford, UK. pp. 47–48.

Kholkunte, S.D. (2008). Database on ethnomedicinal plants of Western Ghats. Final Report 05–07–2005 to 30–06–2008, ICMR New Delhi.

Kiruba, S., Jeeva, S. & Dhass, S.S.M. (2006). Enumeration of ethnoveterinary plants of Cape Comorin, Tamil Nadu. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 5, 576–578.

Krishna T.P.A., Ajeesh Krishna T.P., Chithra, N.D., Deepa, P.E., Darsana, U., Sreelekha, K.P., Juliet, S., Nair, S.N., Ravindran, R., Kumar, K.G.A. & Ghosh, S. (2014). Acaricidal activity of petroleum ether extract of leaves of Tetrastigma leucostaphylum (Dennst.) Alston against Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) annulatus. Hindawi Publishing Corporation. Scientific World Journal, Article ID 715481, 1–6 http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/715481.

Mathias, E. (2006). Livestock keeper’s knowledge verses test tubes and mice: Ethnoveterinary validation and use in animal health care projects. Harvesting Knowledge, Pharming Opportunities. Ethnoveterinary Medicine conference, British Society Animal Science, Writtle College, Chelmsford, UK. pp. 11.

Max, R.A., Buttery, P.J., Kassuku, A.A., Kimambo, A.E. & Mtenga, L.A. (2006). Plant based treatment of round worms: The potential of using tannins to reduce gastrointestinal nematode injection of tropical small rudiments. Harvesting Knowledge, pharming Opportunities. Ethnoveterinary Medicine conference, British Society of Animal Science, Writtle College, Chelmsford, UK. pp. 28–29.

Mini, V. & Sivadasan, M. (2007). Plants used in ethnoveterinary medicine by Kurichya tribe of Wyanada district in Kerala, India. Ethnobot. 19, 94–99.

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R., Mittermeier, C., Da Fonseca, G. & Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity hot-spots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858.

Nair, M.N.B. (2005). Contemporary relevance of Ethno-veterinary medical traditions of India. Proc Natl. Workshop. October 17 and 18 at Kediyur Hotel, Udupi, Mangalore, Karnataka, India.

Nair, M.N.B. & Punniamurthy, N. (eds.) (2010). Ethno-veterinary practices. Mainstreaming traditional wisdom on livestock keeping and herbal medicine for sustainable rural livelihood, I-AIM, 74/2 Jarakabandekaval, Attur post, (via) Yelahanka, Bangalore 560106, India.

Nair, M.N.B. & Unnikrishnan P.M. (2010). Revitalizing ethnoveterinary medical tradition: A perspective from India (Chapter 5). In: David R. Katerere & Dibungi Luseba (Eds.) Ethnoveterinary Botanical Medicine-Herbal Medicine for Animal Health. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis group, USA. pp. 95–124.

Prasad, A.G., Benny, S.T. & Puttaswamy, R.M. (2014). Ethno -veterinary medicines used by tribes in Wayanad District, Kerala. Int. J. Rec. Trends Sci & Tech, 10, 331–337.

Prathipa, A., Senthilkumar, K., Gomathinayagam, S. & Jayathangaraj, M.G. (2014). Ethno-veterinary treatment of Acariasis infestation in rat snake (Ptyas mucosa) using herbal mixture. Int. J. Vet. Sci., 3, 61–64.

Rajagopalan, C.C.R. & Harinarayanan, M. (2003). Veterinary wisdom for the Western Ghats. Amruth 2(2), 15–17.

Rajesh, K., Rajesh N.V., Vasantha, S., Jeeva, S. & Rajashekaran, D. (2014 b). Anthelmentic efficacy of selected ferns in sheeps (Ovis aries Linn.). Int. J. Ethnobiol., Ethnomed., 1,1–14.

Rajesh, K., Rajesh N.V., Vasantha, S. & Geetha, V.S., (2015). Anti-parasitic action of Actinopteris radiata, Acrostichum aureum and Hemionitis arifolia. Pteridology Res, 4, 1–9.

Rajkumar, N. & Shivanna, M.B. (2012). Traditional veterinary healthcare practices in Shimoga district of Karnataka, India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 2, 283–287.

Ramdas, S.R. & Ghtoge, N.S. (2004). Ethno-Veterinary Research in India: An Annotated Bibliography. Anthra, Secunderabad, India.

Raveesha, H.R. & Sudhama, V.N. (2015). Ethno-veterinary Practices in Mallenahalli of Chikmagalur Taluk, Karnataka. J. Med Plants Studies 3, 37–41.

Renjini H., Thangapandian, V. & Binu T. (2015). Ethnomedicinal knowledge of tribe-Kattu-nayakans in Nilambur forests of Malappuram district, Kerala, India. Int. J. Phytotherapy, 5, 76–85.

Rios, J.L. & Recio, M.C. (2005). Medicinal plants and antimicrobial activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 100, 80–84.

Somkuwar, S.R., Chaudhary, R.R. & Chaturvedi, A. (2015). Knowledge of Ethno-Veterinary Medicine in the Maharashtra State, India. Int. J. Sci. Applied Res. 2, 90–99.

Swarup, D. & Patra, R.C. (2005). Perspectives of ethno-veterinary medicine in veterinary Practice. Proceedings of the National conference on Contemporary relevance of Ethnoveterinary medical traditions of India, M.N.B. Nair (ed.). FRLHT, 74/2 Jarakabande Kavel, Attur Post, Yelehanka, Bangalore, 560064, Karnataka, India.

APPENDIX

PLATE 7.1

PLATE 7.2