CHAPTER 9

PLANT-BASED ETHNIC KNOWLEDGE ON FOOD AND NUTRITION IN THE WESTERN GHATS

KANDIKERE R. SRIDHAR and NAMERA C. KARUN

Department of Biosciences, Mangalore University, Mangalagangotri, Mangalore – 574199, Karnataka, India, E-mail: kandikere@gmail.com

CONTENTS

ABSTRACT

The present chapter embodies a brief account on the ethnic plant-based tribal and traditional knowledge prevalent in the Western Ghats fulfilling basic human needs especially food and nutraceuticals. There are several major challenges deriving optimum benefits from the wild plants, which can be augmented by traditional knowledge or experience of tribals and aboriginals. Majority of the past studies in the Western Ghats dealt with floristics in relation to food and medicinal values. A few studies showed multiple applications of wild plant species. The present study has been divided into conventional (fruits and vegetables) nutraceuticals and non-conventional (roots/ rhizomes/tubers) nutritional sources of wild plant species. Five important steps like documentation, vulnerability, conservation, product development and welfare of tribes have been suggested as very important to ethnobotanical research in the Western Ghats. The gaps in our knowledge on ethnic resource of the Western Ghats have been identified and approaches necessary to investigate indigenous knowledge/strategies of conservation of wild plant species are also discussed.

9.1INTRODUCTION

International mega conventions were responsible for understanding the significance of biodiversity, which mitigated exploration and conservation of bioresources throughout the world (CBD, 1992; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005; Finlayson et al., 2011). Major parts of human nutrition and lifestyle requirements are fulfilled by wild or cultivated plant species. We are intimately dependent on plants to meet several demands especially nutrition, medicine, cosmetics, utensils, implements, musical instruments, sports equipments, handicrafts, furniture, boat/ships, jetties, bridges and shelter. The Western Ghats of India being a hotspot of biodiversity, it serves as a storehouse to meet several human needs. There is a major focus of attraction of the world due to its wealth of endemic biota and a wide variety of wildlife. Western Ghats of India is endowed with different vegetation types like moist evergreen, deciduous, semi-evergreen, Shola, grassland, freshwater swamps, bamboo brakes and scrub jungles supporting a wide variety of life forms (Shetty et al., 2002). In recognition of versatility in biodiversity, the UNESCO has recently recognized the Western Ghats as one of the important World Heritage Sites (UNESCO, 2012).

Tribals and village dwellers/rural-folk being intimately associated with forests and wildlife are gifted with the inherent knowledge on the use of forest product for their basic needs. Unlike modern society, they are not amenable for immediate nutritional needs (e.g., food scarcity), health care (e.g., first-aid) and sophisticated shelter. Thus, their inherent or acquired knowledge and skills instantaneously useful to meet their basic requirements like food, medicine and other day to day needs. Tribals also face several threats like scarcity of food, drought, floods and diseases and developed strategies to overcome or to manage such exigencies. The indigenous knowledge of using wild plant species for a specific purpose stems out of experience and interaction with nature as traditional, folklore and tribal. The Western Ghats being rich in tribal communities, tribal knowledge will go long way in recognizing indigenous plant sources, processes and products.

There are several note-worthy publications pertain to ethnobotanical research in the Western Ghats. Karun et al. (2014) inventoried up to 40 villages of Kodagu District of Karnataka to collect information on the use of traditional knowledge in identifying edible fruits from 45 plant species consisting of trees, shrubs, herbs and creepers. It has been proposed to develop sustainable development of fruit-yielding plant species in agroforests in Kodagu. Fruits of Artocarpus hirsutus (monkey jack) possess medicinal principles besides possessing nutritional value as Sarala and Krishnamurthy (2014) projected importance of dried powder of these fruits as indigenous dishes. Wild edible plants from Karnala bird sanctuary in Maharashtra state were enumerated by Datar and Vartak (1975). Gunjakar and Vartak (1982) enumerated wild edible legumes from Pune district of Maharashtra state.

The initial steps necessary to find out usefulness of plant resource in and around us include inventory, identification and documentation. Several studies have been performed in the Western Ghats especially to understand the nutritional and medicinal properties of plant species. Wild fruits provide a change in taste from that used by daily routine. Emphasis has been made on wild edible fruits, which can be immediately used as alternate food sources or as food supplements. Several wild fruits serve as appetizing agents, squashes and digesters. Some of them also serve as medicines (nutraceuticals), fish-poisons and anti-leech agents. Wild fruits are useful to develop several industrial food products like jam, jelly, juice, salted-fruit, wine and soap manufacture. Fruit powders are useful in preparation of a number of dishes either as a whole material or it may serve as ingredient in alternate food preparation. Besides wild fruit, a variety of whole wild plants, leaves stem, flowers, seeds, roots and tubers are used as vegetable. Some of such sources are also consumed directly as raw or cooked or after appropriate processing. Likewise, whole range of plants are in use for medicinal purposes either as a whole plant or after processing. Many wild plants or their parts are used individually or in combination with other ingredients. Besides, some are worth upgrade for production in industrial scale owing to their versatile properties and novel applications. The major focus of this chapter is to consolidate and discuss various aspects of nutritional (fruit, vegetable and non-conventional sources) and nutraceutical perspectives of wild plant species in the Western Ghats based on the ethnic knowledge.

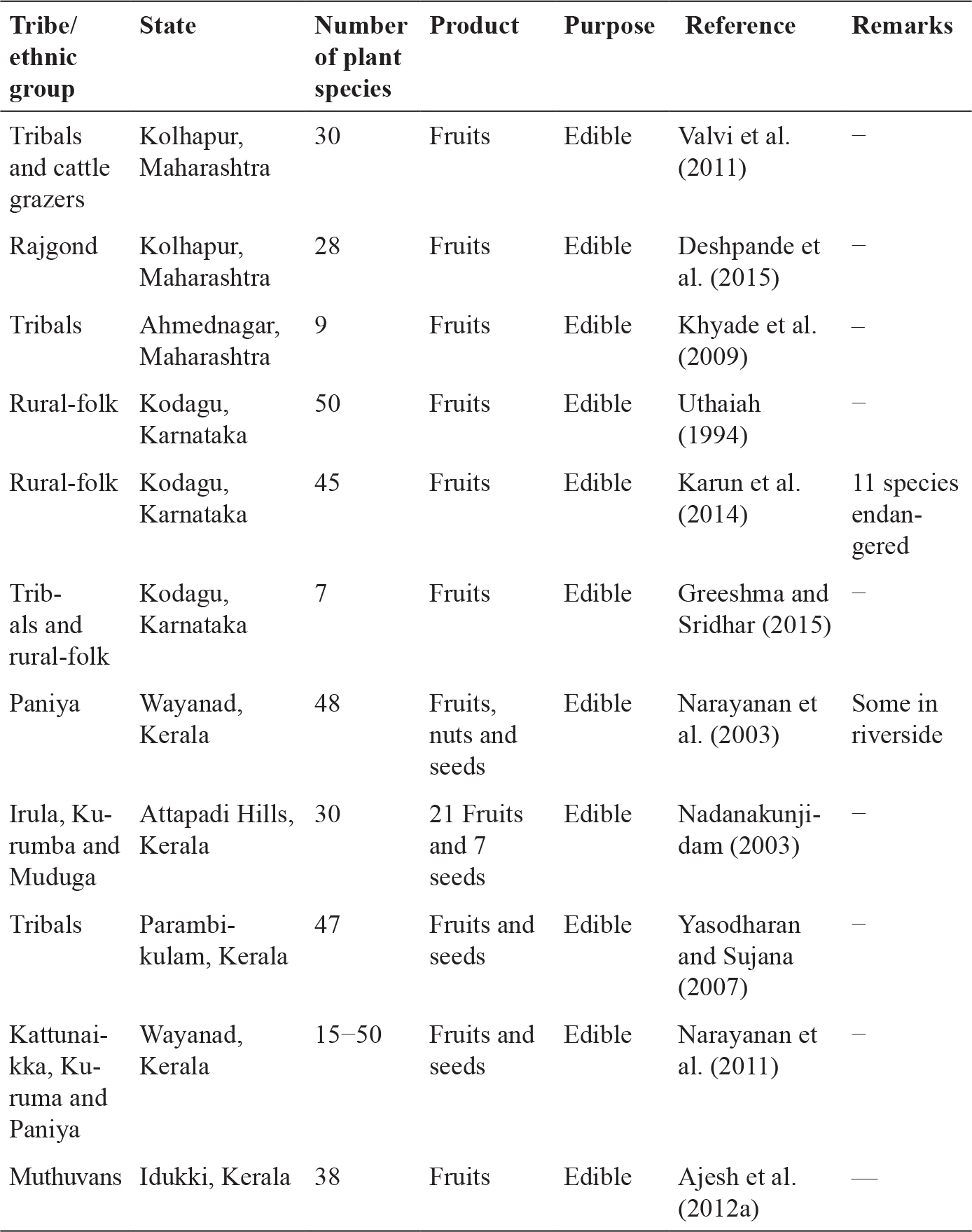

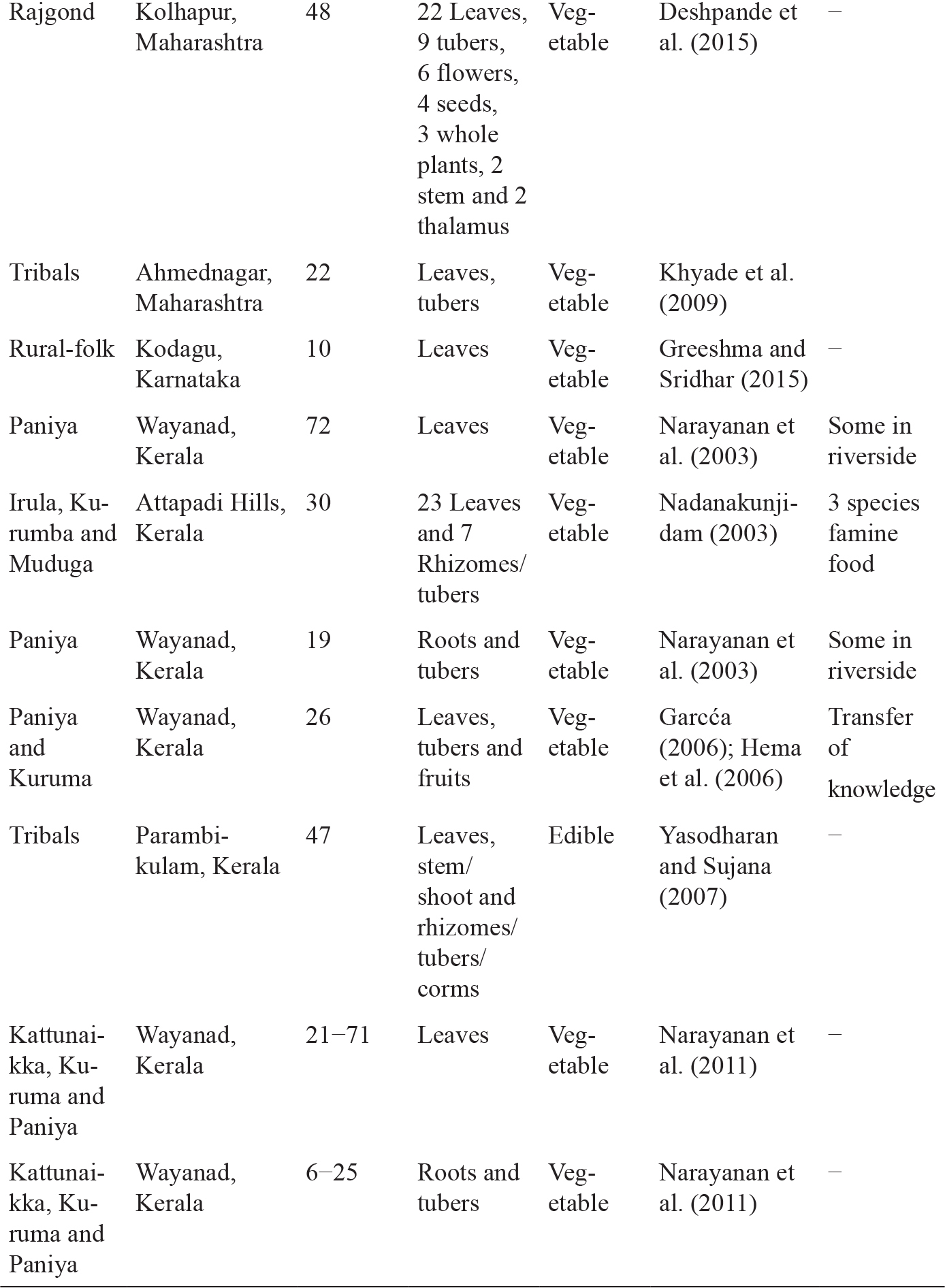

9.2FRUITS

Wild fruits serve as valuable source of nutrients (minerals, proteins and vitamins) and nutraceuticals (antioxidants and edible vaccines). They are also useful in the preparation of wines and squashes. Usually fruits are consumed raw and some needs simple processing before consumption. From the Western Ghats parts of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu a variety of wild fruits are identified and those which are used by the tribal/ethnic communities/rural-folk (Table 9.1; Figure 9.1). Kulkarni and Kumbhojkar (1992) gave an account of wild edible fruits consumed by Mahadeo-Koli tribe in Western Maharashtra. Patil and Patil (2000) reported 36 wild edible angiospermic species used by tribals of Nasik district, Maharashtra. The aboriginies include Bhils, Thakur, Katkari, Warli, Kunbi-kokana and Mahadeo-Koli. Among these unripe or ripe fruits of 10 species are eaten raw. Less known 12 wild edible fruits and seeds of Uttar Kannada district was given by Hebber et al. (2010). Sasi et al. (2011) described 50 wild edible plant diversity of Kotagiri hills – a part of Nilgiri Biosphere reserve, of these 20 are fruits. From the Kolhapur region of Maharashtra, tribals and cattle breeders consume nearly 30 wild fruits (from 3 herbs, 10 shrubs and 17 trees) in raw, and many of them in unripe stage are useful as vegetable and pickle preparation (Valvi et al., 2011). Deshpande et al. (2015) recognized up to 28 wild plant species yielding edible fruits and those are consumed by the Rajgond tribe in Maharashtra. As early as 1990s, Uthaiah (1994) and his associates based on extensive survey in the Western Ghats of Karnataka recognized up to 50 edible fruit-yielding tree species. It was followed by Karun et al. (2014), who recently explored 40 villages to identify 45 plant species (32 trees, 7 shrubs, 3 herbs and 3 creepers) yielding edible fruits and gave commentary on their uses other than consumption as raw. Although these fruits are consumed in raw stage as source of nutrients, many of them have medicinal properties and provide immunity to many diseases of rural-folk. These wild fruits are also popular among tourists of Kodagu region as appetizers, digesters and squashes. Unconventional wild fruits and processing in tribal area of Jawahar, Thane district was discussed by Chothe et al. (2014). Recently, Greeshma and Sridhar (2015) reported nine edible fruits consumed by the villagers and tribes of Kodagu region. Some of them can be consumed as whole fruits, in some rind, pulp, juice and seeds can also be used either for consumption or to prepare several dishes without or with processing. Three tribes (Irula, Kurumba and Muduga) live in Attapadi Hills (Kerala) consume 21 wild fruits, seven seeds and one pod as food source (Nadanakunjidam, 2003). Narayanan et al. (2011) also documented 53 fruits and 9 seeds of wild plant species selectively consumed by three tribes (Kattunaikka, Kuruma and Paniya) in Wayanad. Shareef and Nazarudeen (2015) reported 13 edible raw fruits of tree species belonging to the family Euphorbiaceae distributed in entire Kerala. Interestingly one or the other fruits out of 13 species are available throughout the year for consumption. Fruits of Aporosa cardiosperma, Baccaurea courtallensis and Phyllanthus emblica are the most promising edible fruits. Aporosa bourdillonii, A. in-doacuminata and B. courtallensis are endemic to the Western Ghats. Thirty eight species of wild edible fruits belonging to 25 genera and 17 families used by Muthuvans of Idukki district, Kerala were recorded by Ajesh et al. (2012a).

A versatile plant Trichopus zeylanicus was discovered from the Agasthia Hills of Kerala in the Western Ghats (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trichopus_zeylanicus). Fruits of this plant is used by the Kani tribe to boost their energy as they have anti-fatigue property. Scientists of Tropical Botanical Garden and Research Institute (TBGRI), Kerala successfully formulated and standardized a health drink called ‘Jeevani’ (means, ‘life-giver’), which has been released for commercial production in 1995 by the Arya Vaidya Pharmacy (Mashelkar, 2001). This health drink (or tonic) has been considered equivalent to ‘Ginseng’ (a Korean energy drink) prepared out of roots of Panax ginseng.

Many reports are available on the tribal knowledge on fruits from the Western Ghats of Tamil Nadu. Arinathan et al. (2003b) reported 10 wild fruits (5 edible in unripe stage and 5 edible as raw) consumed by the Palliyar tribe in Tamil Nadu. Up to 20 wild fruits are eaten almost raw and these served as a nutritional source for the tribals of Anaimalai Hills (Sivakumar and Murugesan, 2005). Arinathan et al. (2007) documented 41 wild edible fruit-yielding plant species used by the Palliyar tribe living in the district of Virudhnagar. Many wild fruits are edible in raw stage (Coccinia grandis, Gardenia resinifera, Opuntia stricta, Phyllanthus acidus, Syzygium cumini and S. jambos) and some for culinary purposes (Capsicum frutescens). Under-ripened fruits are used as vegetable (Carica papaya and Coccinia grandis), for preparation of pickles (Carissa carandas, Citrus aurantifolia and Phyllanthus acidus) and juice/squash (Citrus aurantifolia) by the Paliyar tribe (Ayyanar et al., 2010). According to Jeyaprakash et al. (2011) tribes who live in Theni District use five wild fruits extensively for edible purpose. From Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, fruits of 70 less known plant species (27 trees, 24 shrubs, 11 herbs and 8 climbers) used by the six tribes (Irula, Kattunayaka, Kota, Kurumba, Paniya and Toda) were documented by Sasi and Rajendran (2012). These fruits are eaten raw and also serve as potential source for local breweries as tribals trade them. Interestingly, these fruits also serve as nutraceuticals especially in reducing the risks of diseases like cancer, cardiovascular ailments and cataracts. Another report on wild fruits of 30 plant species (11 shrubs, 11 trees, 5 herbs, 2 climbers and 1 parasitic herb) meet nutritional needs of Badaga tribe in the Nilgiri Hills (Sathyavathi and Janardhanan, 2014). As Badaga tribe is aware of these wild plant species, plants are preserved and cultivated wherever possible to improve their economic status. In addition to nutritional properties, therapeutic uses of these fruits are also documented. Many fruits serve in first-aid treatments (e.g., diarrhea, vomiting, headache, toothache and cuts). Likewise, another tribe Irula in Maruthamalai Hills depends on 25 wild plant species as source of fruits (Sarvalingam et al., 2014). The wild jack (Artocarpus hirsutus) has many nutritional properties and can be used for preparation of a wide variety of dishes indigenously on drying and pulverizing and thus may lead to a future potential cottage industry (Sarala and Krishnamurthy, 2014).

9.3VEGETABLES

The wild plant species are also major source of vegetable for the tribals and rural-folk (Table 9.1; Figure 9.1). Studies on wild vegetable comes from the states of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. The Rajgond tribe in Maharashtra consumes nearly 76 wild plant species as vegetables (28 fruits, 22 greens, 9 tubers, 6 flowers, 4 seeds, 3 whole plants, 2 stem and 2 thalamus) either in monsoon season or rest of the year as and when such produce is available (Deshpande et al., 2015). Patil and Patil (2000) reported 36 wild edible angiospermic species used by tribals of Nasik district, Maharashtra. Among them leaves of 14 species, tubers/rhizomes of 4 species, 2 fruits and 1 young shoots are used as vegetable. Three tribals Irula, Kurumba and Muduga residing in Attapady Hills of Kerala use leaves of 23 wild plant species as vegetable (Nadanakunjidam, 2003). Leaves of 72 wild plant species (57 herbs, 11 shrubs and 4 trees) are used by the Paniya tribe in Wayanad (Kerala) as vegetable (Narayanan et al., 2003). Three ethnic communities (Paniya, Kattunaikka and Kuruma) and one migrant community in the Wayanad use leaves of 102 wild plant species as vegetable (Narayanan and Kumar, 2007). Tribals live in Parambikulam (Kerala) utilize leaves of 30 wild plant species and stem/shoot of 6 wild plant species as vegetable (Yesodharan and Sujana, 2007). Anamalai hills, Western Ghats, Coimbatore district were surveyed by Ramachandran (2007) to list out the edible plants utilized by the tribal communities, such as Kadars, Pulaiyars, Malasars, Malaimalasarss and Mudhuvars. About 75 plant species including 25 leafy vegetables, 4 fruit yielding and 45 fruit/seed yielding varieties have been identified. The local tribal communities for their dietary requirements, since a long time have utilized these forest produce. Leaves of 84 wild plant species are selectively useful to three tribes (Kattunaika, Kuruma and Paniya) of Wayanad (Narayanan et al., 2011). Sasi et al. (2011) described 50 wild edible plant diversity of Kotagiri hills – a part of Nilgiri Biosphere reserve. Of these 17 leafy vegetables and 20 tubers/rhizomes are used as vegetable. Greeshma and Sridhar (2015) have reported 10 wild plant species used as vegetables in Kodagu region of Karnataka with indigenous preparation methods.

Edible leaves, edible stem and edible seeds of five wild plant species each consumed by the Palliar tribe in Tamil Nadu have been reported by Arinathan et al. (2003b). Different ethnic groups of Anaimalai region of Tamil Nadu use 53 wild edible plant species as vegetable (Sivakumar and Murugesan, 2005). Of these, leaves of 25 species, wild fruits (as raw) of 20 species and different parts of 8 species (tubers, seeds and roots) are consumed. Ayyanar et al. (2010) carried out an ethnobotanical survey of wild plant species consumed by Paliyar Tribe of Tamil Nadu and reported that 5 plant species are extensively used as vegetable. Besides, these tribals also use pith, flower buds, aril, and bulbils of wild plant species as source of nutrition.

An extensive survey yielded information on leaves (54 species), seeds (45 species), pods (41 species) roots (19 species), pith/apical meristem (12 species) and flowers (10 species) those are nutritionally valuable to the Palliyar tribe in Theni District of Tamil Nadu (Arinathan et al., 2007). Among them, 7 species (Atylosia scarabaeoides, Canavalia gladiata, Entada rheedi, Mucuna atropurpurea, Vigna bournaea, V. radiata and V. trilobata) are endemic and except for two plant species (V. radiata and V. trilobata), the rest are threatened in that region. Deshpande et al. (2015) reported use of whole plants in tender stage as vegetable (e.g., Amaranthus cruentus, Andrographis paniculata and Portulaca oleracea) by Rajgond tribe in Vidharba of Maharashtra, out of which the last one is a weed in agricultural land. Mulay and Sharma (2014) described 85 weed species which are used as vegetables. Among them leaves of 46 species, fruits of 20 species, seeds of 7 species, underground parts of 4 species, flowers of 3 species and tender stems of 4 species are used as vegetables. Details of wild edible species of Amaranthaceae and Araceae used by Kuruma and Paniya tribes in Wayanad district in Kerala were given by Hema et al. (2006). Ajesh et al. (2012b) gave an account on the utilization of wild vegetables used by Muthuvan tribes of Idukki district, Kerala. Around 40 plant species were recorded. Among them 70% species contribute to vegetables by their leaf and stem, 18% by fruit, 8% by tubers, 2% by corm and 2% by calyx. Ashok and Reddy (2012) carried out extensive field surveys in Garbhagiri hills in Ahmednagar district in Maharashtra and reported that 35 species are being used as vegetables. Leaves of 17 plants, fruits of 11 plants, seeds of 3 plants, receptacles, bulbils and flower buds of one plant are being used as vegetables.

9.4NUTRACEUTICALS

Besides fruits and vegetable (given in Sections 9.2 and 9.3), a variety of indigenous plant species worth employing as nutraceutical agents to overcome several diseases are hidden in traditional knowledge. Such knowledge has been spread in Western Ghats especially in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu (Table 9.1; Figure 9.1). Many simple and easily accessible wild plant species besides serving as nutritional source also possess nutraceutical potential. For example, eating raw leaves and fruits of Oxalis comiculata is helpful in preventing stomachache and helps in easy digestion (Lingaraju et al., 2013). Epiphyte Remusatia vivipara (also known as elephant-ear plant) has several edible and medicinal potentials (Asha et al., 2013). This epiphyte grows luxuriously on tree canopies during monsoon and serves as delicacy in Kodagu region. Its leaves and tuber has nutraceuticals as they possess several value-added pharmaceutical properties. Leaves and stem of Justicia wynaadensis are also traditionally used for medicinal purpose in Kodagu region and possess several bioactive principles (phenolics, flavonoids and antioxidants) including natural dye for food coloring and other industrial products (Medapa et al., 2011; Nigudkar et al., 2014) (Figure 9.1). Muthuvans are the prominent tribal group in Kerala following unique culture and ethnobotanical practices to meet the nutraceuticals (Ajesh and Kumuthaklavalli, 2013). Ayyanar and Ignacimuthu (2013) documented 46 wild plant species used as food, 13 wild plants as nutraceuticals by the Kani tribe in Kalakad (Tamil Nadu) and unripe fruits (Artocarpus heterophyllus) and tubers (Manihot esculenta) are the favorite sources. Balakrishnan (2014) has reported ethnomedicinal information of about 35 tuberous plant species used by the tribes Malasar and Muthuvan in Coimbatore and also documented endangered nature of some of these plant species. Fruits of Ziziphus rugosa are edible and flowers are extensively used in treatment of hemorrhage and menorrhea and its bark also useful as astringent and anti-diarrheal (Kekuda et al., 2011). Madappa and Bopaiah (2012) reported various bioactive components of edible fruits of Garcinia gummi-gutta available in the Western Ghats. Recently, detailed studies on nutritional and bioactive component of fruits of Cucumis dipsaceus have also been performed (Chandran et al., 2013; Nivedhini et al., 2014). Arenga wightii, a palm, is a unique source of starch and beverage for Muthuvan tribe of Idukki district in Kerala (Manithottam and Francis, 2007a).

An endangered shurb, Decalepis hamiltonii distributed in the Western Ghats region of Kerala (Kothur Reserve Forest and Palode; also found in Andhra Pradesh) is a potential source of indigenous health drink (Vedavathy, 2004). Roots of this wild plant is called ‘brown gold’ used by the Yanadi tribe in Chittoor (Andhra Pradesh) as a main source of income. These bitter roots consists of 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde (isomer of vanillin) useful as flavoring agent in ice-creams, chocolates and drinks (Thornell et al., 2000). Drinks prepared out of roots serve as an appetizer as well as health tonic as blood purifier and nutraceutical in preventing gastric and intestinal disorders (Vedavathy, 2004). Roots are also used in preparation of chutney as well as pickles with lemon juice. Decalepis hamiltonii is an endangered species and deserves utmost attention for cultivation and utilization for value-added food and nutraceutical products.

9.5NON-CONVENTIONAL SOURCES

One of the popular traditional nutritional sources in the Western Ghats is bamboo shoots. Its use as nutritional source has been restricted owing to high toxic cyanogenic glycosides. Knowledge on removal of such toxins by tribals and rural-folk needs systematic approach for effective marketing and propagation of bamboo germsplasm (Nongdam and Tikendra, 2014). Underutilized velvet bean Mucuna pruriens is nutraceutically valuable as potent source of protein and essential amino acids (Sridhar and Bhat, 2007a; Gurumoorthi et al., 2013). Various non-conventional sources (roots/tubers/ rhizome) used for food have been listed in Table 9.1.

TABLE 9.1Tribes and Ethnic Groups of the Western Ghats Using Wild Plant Species as Food and Nutraceuticals

Tubers of four plant species are utilized as vegetable in Kodagu region of Karnataka with specific method of processing (Greeshma and Sridhar, 2015). Seven rhizomes/tubers constitute vegetable of three tribes (Irula, Kurumba and Muduga) live in Attapadi Hills of Kerala (Nadanakunjidam, 2003). Rhizomes/tubers of Dioscorea bulbifera, D. pentaphylla and D. op-positifolia serve as famine food of these three tribes. Roots and tubers of 19 wild plant species constitute vegetable of Paniya tribe in Wayanad (Kerala) and many of them are confined to riverside marshy regions (Narayanan et al., 2003). Rhizomes/tubers/corms of 10 wild plant species are used as vegetable by tribals of Parambikulam (Kerala) (Yesodharan and Sujana, 2007). Roots and tubers of 6−25 wild plant species constitute selective source of nutrition of three major tribes of Wayanad (Kattunaikka, Kuruma and Paniya) (Narayanan et al., 2011).

Arinathan et al. (2003b) reported edible tubers/rhizomes of five wild plant species used as vegetables by the Palliar tribe in Tamil Nadu. A survey of tribal communities in the Western Ghat region of Tamil Nadu (Coimbatore: Irular, Malasar and Muthuvan) revealed occurrence of 35 tuberous edible plant species (Balakrishnan, 2014). Another important tuber elephant-foot yam (Amorphophallus paeoniifolius) has potential to serve in food industry as it can be easily grown and preserved under normal conditions for prolonged periods. Besides its nutritional value, it has several medicinal properties especially it’s methanolic and hydro-alcoholic extracts possess excellent antioxidant potential (Nataraj et al., 2008). Diplazium esculentum, a riparian fern is commonly used as vegetable (fiddle heads and tender petioles) in Kodagu region of the Western Ghats (Akter et al., 2014; Karun et al., 2014; Greeshma and Sridhar, 2015) (Figure 9.1). Taro starch of Colocasia esculenta is highly digestible compared to conventional starches due to its small grain size (70−80%) (Ahmed and Khan, 2013) (Figure 9.1). This can be achieved with duel advantage as its tuber and leaves are useful as vegetable.

Manithottam and Francis (2007b) discussed ethnobotany of finger millet among Muthuvan tribes of Idukki district, Kerala. Katty is a special dish prepared from the powdered grains of Eleusine by these people. Katty is the unique pudding prepared by the Muthuvans from the grains of finger millet. The dried grains are winnowed, dehusked in an Ural (Ponder) and powdered in a millstone. For 1 kg of powder, 4 L of water is required. Then with constant stirring using two thin strong sticks, the powder is added into the boiling water. At this time, the fire has to be regulated to adjust the softness of the preparation. This is a skilled work and requires some experience. If the stirring is not uniform the hot water will not reach every portion in the powder and if the heat of water is more, pudding will lose its property. After cooling, it is cut into pieces and consumed with or without side dishes

9.6DISCUSSION

Integration of indigenous scientific knowledge of traditional communities or tribals assumes utmost importance to document as well as conserve wild plant resources (Berkes, 2008). Following five important steps that are needed to utilize the natural wild plant resource of the Western Ghats for human welfare: The first step of understanding the bounty of benefits of wild plants needs systematic documentation with geographic indication; Step second needs to follow up the vulnerability of wild plant species to specific environmental conditions and their plasticity to natural calamities; Thirdly, conservation measures to be implemented to enhance specific wild plant species in situ and ex situ; Fourth approach is mode of enforcement of desired technological measures to derive and upgrade products of wild plants; Finally, enhancement of economic benefits and incentives to ethnic population (tribes and aborigines) to uplift their current status through sharing of benefits.

Documentation of traditional knowledge of tribes and aboriginals and geographic indication are the most important steps to overcome biopiracy and helpful in sharing benefits. Floristics of wild plant species needs involvement of trained botanists/technicians to identify the plant species accurately and documentation of availability of such resources consistently or inconsistently (seasonal/annual/perennial) to develop database and future strategies to utilize those resources more effectively in regional scale. Identification of pockets of wild plant resources and possibilities of cultivation in available area would help independence of tribes. Unlike urban population, rural-folk in many developing countries rely on several indigenous food and medicinal plant species to meet their nutritional and nutraceutical needs (Arinathan et al., 2003a; FAO, 2004; Bhat and Karim, 2009; Bharucha and Pretty, 2010). Are there any possibilities to identify a plant resource which can be equivalent to the staple foods like rice, wheat and maize through traditional knowledge of tribes and aboriginals? In Kodagu region of Karnataka for instance, wild fruits of different varieties are available throughout the year and such knowledge would lead to economic gains of tribes exploiting one or the other fruits as staple ones.

Identification and classification of plant species as abundant, endemic, endangered, near endangered, threatened, re-identified and red-listed would help in future research to focus on rehabilitation and regeneration in local geographic conditions. Understanding the regional abiotic/edaphic factors governing distribution and competition of such plant species would help in future domestication. Large scale product-wise mapping based on traditional knowledge and inventories will go long way for in situ and ex situ conservation.

The above assessments lead to employing conservation measures. Several plants are used either as whole or its parts. Those plants used as whole for nutritional and medicinal purposes need priority of conservation. For example, whole plants in tender stage used as vegetable (e.g., Amaranthus cruentus, Andrographis paniculata and Portulaca oleracea) should be conserved on a priority basis (Deshpande et al., 2015). Justicia wynaadensis is another versatile nutraceutical plant species of Kodagu region of the Western Ghats deserves conservation priority (Medapa et al., 2011; Nigudkar et al., 2014; Greeshma and Sridhar, 2015) (Figure 9.1).

FIGURE 9.1Representative wild plant species used as source of food and nutraceuticals by the ethnic groups in Western Ghats. Near ripened fruits of Lycopersicum esculentum (a); ripened fruits of Solanum rudepannum (b); unripe and ripe fruits of Solanum americanum (c); riparian fern Diplazium esculentum (d); edible fiddle heads and tender petioles of D. esculentum (e); leaves (f), flower (g) and fruits (h) of Oxalis esculenta serve as nutraceuticals; leaves of Solanum americanum serve as vegetable (i); shoots of Colocacia esculenta emerging from tuber (j); proliferating tubers of C. esculenta (k); nutraceutically valued plant species Justicia wynaadensis (l).

Techniques to establish repositories (seed or germplasm) will be based on the type of wild plant species. Various methods and strategies are necessary to follow up cultivation and conservation of herbs, climbers, shrubs and tree species. Identification and cultivation in agricultural fields close to the vicinity as hedge plants meet dual purposes of conservation and enhancement of economic gains. Some wild plant species are of special interest as they produce industrially important products. For instance, starch (taro starch) derived from common vegetable plant species (Colocasia esculenta) has high value in food and pharmaceutical industries, which needs immediate attention (Ahmed and Khan, 2013) (Figure 9.1). Similarly, wild fruits of Garcinia gummi-gutta are useful in preparation of products like high value vinegar, wine and also hydroxy citric acid (anti-cholesterol) (Karun et al., 2014). Studies are also available on the use of seeds of itch-bean (Mucuna pruriens) and lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) for nutritional and nutraceutical purposes (Sridhar and Bhat, 2007b; Bhat et al., 2008). Technological progress are necessary to process and preserve the essence and bioactive principles of fruits and wild plant species for prolonged period to gain benefit of nutraceuticals.

Food and health security of tribals and aboriginals are important to help them to continue pass on traditional knowledge from one generation to another. If any wild plant products are patented, some economic gains should be earmarked for tribal rehabilitation and welfare (like education, economic security and improvement of living status). For example, García (2006) projected an interesting connection between mother and child nexus in three socio-cultural groups (Paniya, Kuruma tribes and non-tribals) using wild food plants in Wayanad (Kerala) and its importance. The outcome of this exercise suggested that 26 wild food plants (leaf, tuber and fruit) can be used as nutritional source. This approach serves in prevention of erosion of traditional knowledge and involvement of children paving way for transfer of knowledge as well as future cottage industries. There are several plant species that have the capacity to serve as source of non-conventional products related to nutrition, medicine and other products for sustenance of tribes and aboriginals. Studies on gum-/resin-/dye-yielding, biofuel, essence and flavor from wild plants needs special attention in the Western Ghats.

9.7CONCLUSIONS

The present study projected the traditional knowledge on various wild plant species occurring in the Western Ghats useful in human nutrition and health. Some studies are confined to list the wild plant resources and some projected knowledge of tribes towards their nutrition and nutraceuticals. Although there are some confirmed results for use in human nutrition and health, there are gaps in our knowledge on authenticity of use of parts of wild plant species and processing method needs advanced in vitro and in vivo studies for future applications. Documentation of wealth of traditional knowledge opens up ample opportunities for further progress in nutrition and health. Does the traditional knowledge helps solving protein-energy malnutrition in rural-folks? The scientific validation of several claims needs authenticity on priority to contribute benefits from regional towards global community. There are several approaches to make scientific studies more meaningful. There is a need for integrated approach towards confirmed studies and directions based on the publications on traditional values. For instance, it is possible to focus studies like one nutrient vs. several plant species or one plant species vs. several nutrients, likewise, one disease vs. several plant species or one plant species vs. several diseases. Cultivation of essential wild plant species need to be initiated in plantations and agroforests as an immediate measure. In addition to the current traditional knowledge base, research should orient towards gaining more information regarding wild plant species useful as food, fiber, fodder, fuel and fertilizer as an integrated approach. To progress further in upgrading the wild plant-based perspectives, it is necessary to respect and research the traditional and ethnic knowledge at grass root level. Threats of invasion of alien plant species in forests is one of the important issues to be addressed immediately to save useful wild plant species for future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

KRS acknowledges the University Grants Commission, New Delhi for the award of UGC-BSR Faculty Fellowship. NCK acknowledges Mangalore University for partial financial support through fellowship under the Promotion of University Research and Scientific Excellence (PURSE), Department of Science Technology, New Delhi. Authors are grateful to referees for meticulous corrections of early version of the manuscript.

KEYWORDS

•Aboriginals

•Ethnic Food Plants

•Fruits

•Nutraceuticals

•Vegetables

REFERENCES

Ahmed, A. & Khan, F. (2013). Extraction of starch from taro (Colocasia esculenta) and evaluating it and further using taro starch as disintegrating agent in tablet formulation with overall evaluation. Inventi Rapid: Novel Excipients, 15.

Ajesh, T.P. & Kumuthakalavalli, R. (2013). Botanical ethnography of muthuvans from the Idukki District of Kerala. Int. J. Pl. Anim. Environ. Sci., 3, 67−75.

Ajesh, T.P., Naseef, S.A.A. & Kumuthakalavalli, R. (2012a). Ethnobotanical documentation of wild edible fruits used by Muthuvan tribes of Idukki, Kerala – India. Int. J. Pharm. Bio Sci, 3(3), 479–487.

Ajesh, T.P., Naseef, S.A.A. & Kumuthakalavalli, R. (2012b). Preliminary study on the utilization of wild vegetables by Muthuvan tribes of Idukki district of Kerala, India. Int. J. Appl. Biol. Pharmaceut. Tech. 3, 193–199.

Akter, S., Hossain, M.M., Ara1, I. & Akhtar, P. (2014). Investigation of in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of Diplazium esculentum (Retz.). Sw. Int. J. Adv. Pharm. Biol. Chem., 3,723−733.

Arinathan, V., Mohan, V.R. & De Britto, A.J. (2003a). Chemical composition of certain tribal pulses in South India. Int. J. Food Sci., 54, 209−217.

Arinathan, V., Mohan, V.R., De Britto A.J. & Chelladurai, V. (2003b). Studies on food and medicinal plants of Western Ghats. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot., 27, 750−753.

Arinathan, V., Mohan, V.R., De Britto, A.J. & Murugan, C. (2007). Wild edibles used by Palliyars of the Western Ghats, Tamil Nadu. Indian J. Trad. Know., 6, 163−168.

Asha, D., Nalini, M.S. & Shylaja, M.D. (2013). Evaluation of phytochemicals and antioxidant activities of Remusatia vivipara (Roxb.) Schott., an edible genus of Araceae. Der Pharmacia Lettre, 5, 120−128.

Ashok, S. & Reddy, P.G. (2012). Some less known wild vegetables from the Garbhagiri hills in Ahmednagar district (M.S.) India. J. Pharmaceut. Res. and Opinion, 2(1), 9–11.

Ayyanar, M. & Ignacimuthu, S. (2013). Plants used as food and medicine: an ethnobotanical survey among Kanikaran community in South India. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Safety 3, 123−133.

Ayyanar, M., Sankarasivaraman, K., Ignacimuthu, S. & Sekar, T. (2010). Plant species with ethno botanical importance than medicinal in Theni district of Tamil Nadu, southern India. Asian J. Exp. Biol. Sci., 1, 765−771.

Balakrishnan, S.B. (2014). Ethnomedicinal importance of wild edible tuber plants from tribal areas of Western Ghats of Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India. Life. Sci. Leaflets, 58, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1234/lsl.v58i0.154

Berkes, F. (2008). Sacred ecology: Traditional ecological knowledge and management systems. Taylor and Frances, Philadelphia and London.

Bharucha, Z. & Pretty, J. (2010). The roles and values of wild foods in agricultural systems. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. B., 365, 2913−2926.

Bhat, R. & Karim, A.A. (2009). Exploring the nutritional potential of wild and underutilized legumes. Compare. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safety, 8, 305−331.

Bhat, R., Sridhar, K.R., Young, C.-C., Arun, A.B. & Ganesh, S. (2008). Composition and functional properties of raw and electron beam irradiated Mucuna pruriens seeds. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol., 43, 1338−1351.

CBD (1992). Convention for Biological Diversity – Strategic Plan for biodiversity 2011–2020: http://www.cbd.int/decision/cop/?id=12268.

Chandran, R., Nivedhini, V. & Parimelazhagan, T. (2013). Nutritional composition and antioxidant properties of Cucumis dipsaceus Ehrenb. ex Spach leaf. The Sci. World J., 1−9, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/890451.

Chothe, A., Patil, S. & Kulkarni, D.K. (2014). Unconventional wild fruits and processing in tribal area of Jawahar, Thane district. Bioscience Discovery 5(1), 19–23.

Datar, R. & Vartak, V.D. (1975). Enumeration of wild edible plants from Karnala Bird Sanctuary, Maharashtra State. Biovigyana., 1, 123–129

Deshpande, S., Joshi, R. & Kulkarni, D.K. (2015). Nutritious wild food resources of Rajgond tribe, Vidarbha, Maharashtra State, India. Indian J. Fund. Appl. Life Sci., 5, 15−25.

FAO (2004). Annual Report: The state of food insecurity in the world, monitoring the progress towards the world food summit and millennium development goals. Food and Agricultural Organization, Rome.

Finlayson, C.M., Carbonell, M., Alarcó, T. & Masardule, O. (2011). Analysis of Ramsar’s guidelines for establishing and strengthening local communities’ and Indigenous peoples’ participation in the management of wetlands (Resolution VII.8). In: Science and local communities – Strengthening partnerships for effective wetland management, Carbonell, M., Nathai-Gyan, N. & Finlayson C.M. (eds.). Ducks Unlimited Inc., Memphis, USA, pp. 51–56.

García, G.S.C. (2006). The mother – child nexus: knowledge and valuation of wild food plants in Wayanad, Western Ghats, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed., 2, 1−6.

Greeshma, A.A. & Sridhar, K.R. (2015). Ethnic plant-based nutraceutical values in Kodagu region of the Western Ghats. In: Biodiversity in India, Volume # 8, In: Pullaiah, T. & Rani, S. (eds.). Regency Publications, New Delhi, pp. 299−317.

Gunjakar, N. & Vartak, V.D. (1982). Enumeration of wild edible legumes from Pune district, Maharashtra state. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. 31, 1–9.

Gurumoorthi, P., Janardhanan, K. & Kalavathy, G. (2013). Improving nutritional value of velvet bean, Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC. var. utilis (Wall. ex. Wight) L.H. Bailey, an underutilized pulse, using microwave technology. Indian J.Trad. Knowl., 12, 677−681.

Hebbar, S.S., Hegde, G. & Hegde, G.R. (2010). Less known wild edible fruits and seeds of Uttar Kannada district of Karnataka. Indian Forester, 136(9), 1218–1222.

Hema, E.S., Sivadasan, M. & Anilkumar, N. (2006). Studies on edible species of Amaranthaceae and Araceae used by Kuruma and Paniya tribes in Wayanad district, Kerala, India. Ethnobotany 18(1), 122–126.

Jeyaprakash, K., Ayyanar, M., Geetha, K.N. & Sekar, T. (2011). Traditional uses of medicinal plants among the tribal people in Theni District (Western Ghats), Southern India. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed., S20−S25.

Karun, N.C., Vaast, P. & Kushalappa, C.G. (2014). Bioinventory and documentation of traditional ecological knowledge of wild edible fruits of Kodagu-Western Ghats, India. J. For. Res., 3, 717−721.

Kekuda, P.T.R., Raghavendra, H.L. & Vinayaka, K.S. (2011). Evaluation of pericarp of seed extract of Zizypus rugosa Lam. for cytotoxic activity. Int. J. Pharmaceut. Biol. Arch., 2, 887−890.

Khyade, M.S., Kolhe S.R. & Deshmukh, B.S. (2009). Wild Edible Plants used by the Tribes of Akole Tahasil of Ahmednagar District (MS), India. Ethnobotanical Leaflets 13, 1328–1336.

Kulkarni, D.K. & Kumbhojkar, M.S. (1992). Ethnobotanical studies on Mahadeo Koli tribe in western Maharashtra Part III Non-conventional wild Edible fruits. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. 10, 151–158.

Lingaraju, D.P., Sudarshana, M.S. & Rajashekar, N. (2013). Ethnopharmacological survey of traditional medicinal plants in tribal areas of Kodagu district, Karnataka, India. J. Pharm. Res. 5, 284297.

Madappa, M.B. & Bopaiah, A.K. (2012). Preliminary phytochemical analysis of leaf of Garcinia gummi-gutta from Western Ghats. IOSR J. Pharm. Biol. Sci., 4, 17−27.

Manithottam, J. & Francis, M.S. (2007a). Arenga wightii Griff. – A unique source of starch and beverage for Muthuvan tribe of Idukki district, Kerala. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 6(1), 195–198.

Manithottam, J. & Francis, M.S. (2007b). Ethnobotany of finger millet among Muthuvan tribes of Idukki district, Kerala. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 6(1), 160–162.

Mashelkar, R.A. (2001). Intellectual property rights and the Third World. Curr. Sci, 51, 955−965.

Medapa, S., Singh, G.R.J. & Ravikumar, V. (2011). The phytochemical and antioxidant screening for Justicia wynaadensis. Afr. J. Plant Sci., 5, 489−492.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and human wellbeing: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington, DC.

Mulay, J.R. & Sharma, P.P. (2014). Some underutilized plant resources as a source of food from Ahmednagar District, Maharashtra, India. Discovery, 9(23), 58–64.

Nadanakunjidam, N. (2003). Some less known wild food plants of Attapadi Hills, Western Ghats. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot., 27, 741−745.

Narayanan, M.K.R. & Kumar, N.A. (2007). Gendered knowledge and changing trends in utilization of wild edible greens in Western Ghats, India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl., 6, 204−216.

Narayanan, M.K.R., Kumar, N.A. & Balakrishnan, V. (2003). Uses of wild edibles among the Paniya tribe in Kerala, India, In: Conservation and Sustainable Use of Agricultural Biodiversity: A Source Book. CIP-UPWARD, Philippines, pp. 100−108.

Narayanan, M.K.R., Kumar, N.A., Balakrishnan, V., Sivadasan, M., Alfarhan, H.A. & Alatar, A.A. (2011). Wild edible plants used by the Kattunaikka, Paniya and Kuruma tribes of Wayanad District, Kerala, India. J. Med. Pl. Res., 5, 3520−3529.

Nataraj, H.N., Murthy, R.L.N. & Shetty, S.R. (2008). In vitro antioxidant and free radical scavenging potential of Amorphophallus peoniifolius. Orient. J. Chem. 24, 895−902.

Nigudkar, M., Patil, N., Sane, R. & Datar, A. (2014). Preliminary phytochemical screening and HPTLC fingerprinting analysis of Justicia wynaadensis (Nees). Int. J. Pharma Sci., 4, 601605.

Nivedhini, V., Chandran, R. & Parimelazhagan, T. (2014). Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Cucumis dipsaceus Ehreng. ex Spach fruit. Int. Food Res. J. 21, 1465−1472.

Nongdam, P. & Tikendra, L. (2014). The nutritional facts of bamboo shoots and their usage as important traditional foods of Northeast India. Int. Schol. Res. Not., 1−17; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/679073

Patil, M.V. & Patil, D.A. (2000). Some more wild edible plants of Nasik district (Maharashtra). Ancient Science of Life, 19(3&4), 102–104.

Ramachandran, V.S. (2007). Wild edible plants of the Anamalais, Coimbatore district, Western Ghats, Tamil Nadu. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 6(1), 173–176.

Sarala, P. & Krishnamurthy, S.R. (2014). Monkey jack: underutilized edible medicinal plant, nutritional attributes and traditional foods of Western Ghats, Karnataka, India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl., 13, 508−518.

Sarvalingam, A., Rajendran, A. & Sivalingam, R. (2014). Wild edible plant resources used by the Irulas of the Maruthamalai Hills, Southern Western Ghats, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Res. 5, 198−201.

Sasi, R. & Rajendran, A. (2012). Diversity of wild fruits in Nilgiri hills of the southern Western Ghats – ethnobotanical aspects. Int. J. Appl. Biol. Pharmaceut. Technol., 3, 82−87.

Sasi, R., Rajendran, A. & Maharajan, M. (2011). Wild edible plant Diversity of Kotagiri Hills – a Part of Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, Southern India. J. Research in Biol., 2, 80–87.

Sathyavathi, R. & Janardhanan, K. (2014). Wild edible fruits used by Badagas of Nilgiri District, Western Ghats, Tamilnadu, India. J. Med. Pl. Res., 8, 128−132.

Shareef, S.M. & Nazarudeen, A. (2015). Utilization of potential of Euphorbiaceae wild edible fruits of Kerala, a case study. J. Non-Timber For. Prod., 22, 2529.

Shetty, B.V., Kaveriappa, K.M. & Bhat, K.G. (2002). Plant resources of Western Ghats and lowlands of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi Districts. Pilikula Nisarga Dhama Society, Mangalore.

Sivakumar, A. & Murugesan, M. (2005). Ethnobotanical studies on the wild edible plants used by the tribals of Anaimalai hills, the Western Ghats. Ancient Sci. Life 25, 1−4.

Sridhar, K.R. & Bhat, R. (2007a). Agrobotanical, nutritional and bioactive potential of unconventional legume – Mucuna. Livest. Res. Rural Develop., 19, Article # 126: http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd19/9/srid19126.htm

Sridhar, K.R. & Bhat, R. (2007b). Lotus – A potential nutraceutical source. J. Agric. Technol., 3, 143−155.

Thornell, K., Vedavathy, S., Mulhooll, D.A. & Crouch, N.R. (2000). Parallel usage pattern of African and Indian periplocoids corroborate phenolic root chemistry. South Afr. Enthnobot., 2, 17−22.

UNESCO (2012). United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. World Heritage Center: www.unesco.org/en/list/1342

Uthaiah, B.C. (1994). Wild edible fruits of Western Ghats – A survey. Higher plants of Indian subcontinent. Additional series of Indian Journal of Forestry, 3, 87–98.

Valvi, S.R., Deshmukh, S.R. & Rathod, V.S. (2011). Ethnobotanical survey of wild edible fruits in Kolhapur District. Int. J. Appl. Biol. Pharmaceut. Technol., 2, 194−197.

Vedavathy, S. (2004). Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn. – an endangered source of indigenous health drink. Nat. Prod. Rad., 3, 22−23.

Yesodharan, K. & Sujana, K.A. (2007). Wild edible plants traditionally used by the tribes in the Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala, India. Nat. Prod. Rad., 6, 74−80.