“A shamanic practitioner I worked with once said, ‘Learn and live by your own body’s rhythm.’ Simple, but it profoundly affected me by making me aware of what my body needs and understanding what it is and isn’t capable of If we don’t learn to manage our energy ourselves, there will be plenty of people, projects, and events that will do it for us And no one will ever be wiser about our needs than we are.”

— FACEBOOK FRIEND MICHELE LAWSON

During the worst relationship of my life (I’ll spare you the gruesome details), I broke out in a strange rash that covered my abdomen, buttocks, and thighs. “Dry skin,” the first dermatologist remarked, but lotion wasn’t the cure. A second dermatologist surveyed the rash with concern and sent her assistant to fetch a biopsy kit. She was worried that the rash might be a lymphoma, but it proved to be a noncancerous infiltrate of lymphocytes (immune cells) into my skin. Typically an ailment that afflicts adolescent males and clears up in a few weeks, my case was chronic and persisted for more than two years. I was an outlier in the annals of dermatology—a cover girl for the odd.

My doctor wanted to start me on chemotherapy. Even though the condition wasn’t cancerous, there didn’t seem to be any other way to clear up the persistent rash. I declined since the potential cure seemed altogether worse than the disease. Fascinated with mind-body medicine, I was more interested in the person with the illness than the disease itself. How were these rough red blotches related to the story of my life?

My ill-chosen lover came directly to mind. He was a person of great promise in many regards, but also someone of monumental brokenness. Ever idealistic—my assistant, Luzie, calls me an innocent—I hoped that my sweet, sweet love would save him. I apparently missed my true calling as a country singer. Light enters at the broken places was my mantra.

The trouble was that because I was so fixated on him, I couldn’t see my own brokenness. I’ve had a lifelong tendency to indiscriminately offer up my jugular vein to all comers, and the result has often been nothing short of a disastrous loss of energy culminating in burnout. Rather than protecting myself and setting limits, I had allowed my boyfriend (who was the latest manifestation of my pathological idealism) to invade every aspect of my life. By doing so, my health, finances, friendships, work, and peace of mind all took a huge hit. Had I paid more attention to what my body was trying to tell me through the rash, I might have bailed on the toxic relationship sooner, but idealists often stay in bad situations too long, hoping for a miracle.

You can view your immune system as a kind of internal militia that keeps invaders from taking over. It manufactures antibodies that prevent bacteria, viruses, and fungi from colonizing your body and sucking the life out of you. An inflammatory response (like the rash on my skin) is the body’s way of setting a strong boundary to keep itself intact. Your skin is your other source of protection. It’s a physical barrier that separates you from the rest of the world. Think about it. Without skin, it would be impossible to take a bath or get dressed! You’d just leak all over the place.

So my illness was a double-barreled metaphor involving two boundary organs—the immune system and skin. It was perfect for getting the attention of someone as dense and headstrong as I can be. I had succumbed to a near deadly invasion by a person whom I had willingly allowed to drain my life-force energy. This was a bitter pill to swallow, since I don’t buy the oversimplified view that illnesses always convey a deeper symbolic meaning about the self. But this one surely did, at least for me.

The combination of idealism, weak boundaries, and helper’s disease (“I can save him!”) is like nitroglycerin. It has the potential not only to burn you out . . . but worse still, to blow you up. When I could finally admit that I’d given all of my energy to a human vampire, I left the relationship. Within two months of acting on my body’s wisdom and taking back my power (as well as my life), the rash disappeared for good.

FBF Betsy Mullen shared some powerful advice she received on this topic from her dear friend and mentor Antoinette Spurrier:

A lot of times, if we believe we’re moving toward a greater vision, we also feel that we can be the sacrificial lamb. But if we allow our spirit—our spiritual core—to get violated repeatedly without standing up for ourselves, we are in a place of not acting in merit toward our own spiritual nature. When we look at our desire to help others, maybe too much of our power gets transferred. In the desire to bring forward the higher goal, perhaps there are levels of repeated violations that we allow, because we have transferred our authority. But what is the greater spiritual good if we violate our own wellness at a physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual level?

Ironically, “self-violation” is common both in healthcare providers and among the clergy. FBF Teri Gilmore wrote the following:

As a clergyperson, I can attest to many cases of burnout in the priesthood. Much of it comes from inappropriate boundaries—not knowing how to set limits on time when we are available to parishioners (that is what caller ID and message machines are for), not taking two whole days off each week, not taking long enough vacations, and trying to be everything to everyone.

There’s a lot of talk about balancing our own needs with the needs of others. But without a vision that transcends the polarity between maintaining strong boundaries and offering help to others, the road to balance is hard to find. However, Kabbalism—the ancient mystical teaching of the Zohar (the classic text of Jewish mysticism)—has just such a vision.

Creating a “Beautiful Synthesis”

First let me offer a very short course on the Kabbalistic “Tree of Life,” which is no less than the software program for Creation. (Whether or not this jibes with the creation story you prefer, just consider the following as a metaphor that can help you understand how to balance your own energy system.)

I remember lying in bed as a child and wondering how something—how everything—could have possibly arose from nothing. Fortunately, Kabbalah offers an answer to that intriguing question. Here is a summary of how that happens.

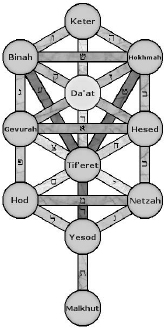

The Tree of Life comprises ten luminous globes of energy (light) called the sephiroth, and each individual sephira is a Divine attribute—a pattern of energy— through which God creates the continuously evolving universe. The sephiroth are in dynamic interaction within and between four interconnected Trees of Life, which manifest four worlds of creation, from the most subtle to our densest material world. These worlds correspond roughly to the human mind, soul, heart (emotions), and body.

At the top of the tree sits the first sephira, known as Keter—“the Crown.” It represents the will of the Absolute to step out of itself in the form of a Creator that emanates the seen and unseen universes. That is how something appears out of nothing.

Sephiroth two through seven (from right to left down the Tree of Life, excluding the one labeled Da’at) form pairs of opposites. For example, the fourth sephira Hesed, which means loving-kindness, is balanced by Gevurah, the fifth sephira meaning strength or boundaries. These two opposing principles combine (similar to the Taoist yin and yang) and give rise to the sixth sephira called Tif’eret, which is the emanation of the Divine Will as beauty, balance, and harmony.

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life illustrating the ten sephiroth. (The lighter colored sphere labeled Da’at is a subconscious mirror of Keter and isn’t counted.)1

Rabbi Shimon Leiberman, writing for the Jewish Website www.aish.com, describes how the balance of Hesed and Gevurah creates the transcendent energy of Tif’eret, which he calls a “beautiful synthesis.” His understanding sheds light on how we can manage the urge to tend, befriend, rescue, and help with the need to maintain our own boundaries in a way that encourages others to find and mobilize their own strengths.

Leiberman uses the example of a democracy whose leader has to ensure the survival of the nation. To that end, there’s a state department (Hesed, sometimes spelled “Chesed“) whose job is to cultivate good relations among nations. There’s also a department of defense (Gevurah) whose job is to prepare for war. The essential goals and philosophies of these two departments are completely at odds.

How can they be reconciled? Is there a worldview that includes yet transcends these disparate positions? A broader perspective—to ensure economic and human development while keeping its citizens safe and boundaries intact—is provided by the vision of the nation’s leader. Sometimes military might is the necessary strategy, while at other times, it is friendship and understanding. Wisdom lies in knowing when to use each, without adopting either one as a sole ideology. Leiberman explains:

Chesed [Hesed] has an innate “ideology” of goodness. It wants to give for the sake of giving. It sees in this the ultimate goal, and the more one gives—regardless who is deserving—the greater and better things.

Gevurah, on the other hand, sees giving as poisonous. Only things earned by equal and fair labor are “good.” Thus, it has a powerful ideology of “quid pro quo” and “no free lunches.” It sees the ultimate goal of creation as every creature earning its own way.

Tiferet comes along creating a synthesis of both of these approaches. It includes both of these approaches because it has a broader goal in mind, and therefore makes use of both. Its goal is “the development of the human being to his greatest potential.”2

Extending the metaphor to our own lives, if we constantly push ourselves to do more, serve more, love more, and give more, the ideology of Hesed will cause us to burn out. That’s exactly what happens to many idealistic people who work in the human-services sector. Learning how to take care of oneself is indeed an art—one that I’ve addressed in my books Inner Peace for Busy People and Inner Peace for Busy Women

We also need to know when, how, and under what circumstances to mobilize Gevurah When I was writing this book, for instance, I needed to establish very strict boundaries so that I could carve out blocks of uninterrupted time. If you e-mailed me during this period, you would have received this autoreply: “I am either traveling or on retreat meeting a pressing book deadline. No matter who you are and how much I love you, I am unavailable for e-mail, visits, or phone calls until mid-February. No exceptions! Contact my assistant, Luzie, at . . .”

FBF Lauren Rosenfeld, also a student of Kabbalah, made an insightful point about Gevurah as discernment— the art of sensing which activities, tasks, or people to let in (or keep out of) your life at any given time so that you can live in the most inspired way.

Lauren posted this during our discussion:

We tend to think about Divine inspiration as an unbridled outpouring of Divine light. But sometimes, it comes in the form of discernment: the wisdom and strength to intuitively know what we will allow in and what we have the strength to turn away. In Kabbalah, Gevurah— strength/limitation/judgment—is indeed a Divine energy. We can get in touch with the Divine power of discernment and know what we should limit in our lives.

Coming to Balance

Knowing what to limit in your life and what to seek more of isn’t always easy to figure out, let alone implement. The tendency for all idealists—and for most women, whether idealistic or not—is to give selflessly until they drop.

Bob Mason, a friend of mine who has devoted years to learning the ways of the Pueblo Indians, once returned from a ceremonial dance and told me about an insight he received during a “giveaway.” (A giveaway is a ceremony where you place a treasured belonging on a blanket for someone else to have. You, too, can then take something that you need, so the ceremony is reciprocal, and all participants are helped.) Bob heard an inner voice during the giveaway that simply said, Do not place yourself on the giveaway blanket because you are not yours to give

When you give away what isn’t yours in the first place—the vitality of your soul—you’re engaging in an act of self-sabotage. Your generosity, while it may appear selfless on the surface, is really selfish in that it serves the ego (the desire to be right, look good, feel accepted, be rewarded, feel holy, and so forth) rather than the soul’s purpose, which is uniquely yours. Serving the ego is draining, but serving the soul is energizing.

FBF Gina Vance wrote:

It is helpful to ask whom we serve and why, especially on less-than-conscious levels of awareness. For that which drives us to extinguishment may be something like: “If only I give enough to this idealized God figure I am serving and sacrificing for, then I will someday be returned the favor [ultimately love].”

Love is always the answer. But the question is how to honor and love ourselves so that our actions serve the soul. The soul cooperates with the Tree of Life—that larger field of creative energy. The ego, on the other hand, is powered by our own limited adrenal energy that eventually burns out. Paying attention to our energy, and how various acts affect it, is instrumental in learning how to discern where right boundaries are at any moment.

FBF Sheila Weidendorf wrote:

Limits can be liberating—meaning that we can’t do everything, every day, all the time. If no doesn’t really mean no, then yes is meaningless as well. A little self-awareness and the willingness to set boundaries can go a long, long way in maintaining balance in work and life.

Determine where the world’s needs and your own personal skill and joy intersect, and then put your apples in that basket. Be clear about what you can and cannot offer, and respect your own boundaries so that others will respect them, too. Then work is joyful, balance is a foundational principle, and there’s less there to cause burnout.

Sheila offers a very clear definition of self-love, which I think of as a Divine attribute that resides within each of us. Another vital aspect of this is asking for help. FBF Joe Buchman described how this has impacted his life:

Taking care of a terminally ill spouse can be overwhelming. Burnout seemed to creep up on me overnight. I had to force myself to slow down and take a break, and realize that everything doesn’t have to be perfect. I’ve also learned to accept help. I have a bag of “emotional tools” I use: I manage my stress with healthy eating, yoga, and meditation; and I try to get a good night’s sleep each night. I’m so grateful to my brother who gives me the time to put those tools to good use.

FBF Lauren Rosenfeld agreed, saying:

For me, the antidote to burning out is reaching out. When I’m feeling burned out, it’s usually a result of my belief that I can do it alone . . . that I can handle it all myself. When burnout hits, I want to retreat, which is more of the same, isn’t it? I can do it all by myself; I can recover by myself And so I reach out. I allow others to do for me, to support me, to enfold me. To make me tea or make me laugh. “I am who I am because of who you are,” says the wise, laughing heart. And it is with a wise and laughing heart—a heart that listens to and rejoices with others—that I reemerge renewed.

“If only the world I work in would catch up with this level of consciousness,” commented FBF Lavinia Gene Weissman during our wonderful conversation on boundaries and self-love. The next chapter deals with what to do when your workplace doesn’t understand the conversation, and it’s time to let go and move on.