2 | Violent Crime and Violent Criminals

No distinction plays a larger role in contemporary American criminal law than the line between violent and nonviolent offenses. We take it for granted that violent crimes are the serious crimes, the ones that deserve stiffer sentences. The Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation divide the index crimes tracked by the Bureau into two groups—“violent crime” (murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault) and “property crime” (burglary, larceny, motor vehicle theft, and arson)—and the composite figure for violent crime gets far more news coverage than the comparable figure for property crime. State and federal laws prescribe especially harsh sentences for violent repeat offenders. Most states also make it harder for persons convicted of violent offenses to be released on parole. They make it more difficult, as well, for violent offenders to avoid incarceration altogether: more often than not, drug courts and other programs aimed at diverting offenders from prison exclude defendants charged with violent crimes. Some states also make violent crimes ineligible for sealing or expungement, no matter how much evidence there is of rehabilitation, and it is common for people convicted of violent crimes to be barred statutorily from particular forms of employment. The special restrictions applied to people convicted of violent crimes create what one legal scholar calls a kind of “third-class citizenship”—a “permanently degraded social status” significantly worse than the consequences following from other criminal convictions. Even before conviction, though, defendants charged with violent offenses are often singled out for harsher treatment. Just to give one example, in Nebraska defendants accused of violent crimes cannot claim the usual evidentiary privileges that protect the confidentiality of spousal communications and prevent spouses from having to testify against each other. The assumption that violent crimes are the most serious crimes, the ones most deserving of harsh punishment, runs throughout our system of criminal law.1

Even advocates of reducing prison sentences, and improving the treatment of prisoners after their release, often treat violence as something of a third rail. As one commentator complained, nonviolent offenders “have received almost all of the reform attention”; they have been “separated rhetorically from the ‘violent’ types who are generally considered beyond redemption or mercy.” A 1994 report by the federal Department of Justice on the treatment of “low-level offenses” took it for granted that only “nonviolent” offenses could be considered “low-level,” because part of what it meant for an offense to be “low-level” was that the perpetrator was not particularly likely to be violent in the future. Critics of “recidivist enhancement” statutes often fault such statutes for targeting offenses that are not necessarily violent, like burglary, and excluding some violent offenses, such as assault. As district attorney of San Francisco in the early 2000s, Kamala Harris argued against overreliance on long prison terms—except for violent crimes. Violent offenders, she explained, “have crossed a line that we simply will not tolerate” and need to be “remove[d] … from our midst.” In 2015, when there was a bipartisan push for sentencing reform in Congress, a bill to mitigate the effects of federal mandatory minimum sentences drew criticism for benefiting offenders who had been convicted in the past of violent offenses; the bill’s sponsors responded by amending the legislation “to ensure violent criminals do not benefit.” A report in the year 2020 by the Prison Policy Initiative, an advocacy group opposed to mass incarceration, concluded that “almost all of the major criminal justice reforms passed in the last two decades explicitly exclude people accused and convicted of violent offenses.”2

The fundamental assumption that only nonviolent offenders deserve lenience was vividly illustrated in 2016 when California voters approved a ballot initiative (Proposition 57) to make it easier for some prisoners to be considered for release on parole. Unsurprisingly, the measure was limited to prisoners convicted of nonviolent crimes, but much of the public debate over the initiative had to do with whether, notwithstanding its language, it might wind up helping violent offenders. Opponents, including most of the state’s elected prosecutors, argued in the ballot pamphlet sent to voters that the initiative “APPLIES TO VIOLENT CRIMINALS.” Supporters, including California governor Jerry Brown, insisted that the new law would “NOT authorize parole for violent offenders.”3

Part of the difficulty was that the initiative did not itself define “nonviolent felony.” Supporters pointed to California’s determinate sentencing law, which imposed stiff sentence enhancements for defendants repeatedly convicted of “violent felonies” and then defined the offenses that qualified—a list that included murder, voluntary manslaughter, rape, sexual assault, robbery, extortion, kidnapping, child molestation, mayhem, burglary of an occupied dwelling, and a range of other felonies. After voters approved the initiative, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation promulgated regulations confirming that “nonviolent felonies” under the new law meant felonies not listed as “violent” in the determinate sentencing law. Opponents complained—before and after the passage of Proposition 57—that this definition left out many violent offenses, including, for example, assault with a deadly weapon, rape by intoxication, hostage taking, and arson. Governor Brown countered during the initiative campaign that the statutory list had been augmented in 2000 by a ballot measure backed by the California District Attorneys Association, and if they thought other crimes should be treated as “violent,” they should have added those offenses. The district attorneys had “created the damn violent list,” the governor charged. (In 2020 another initiative was placed on the California ballot, this one aimed at restoring some of the severity of the state’s sentencing laws: a key part of the measure expanded the list of crimes defined as violent.)4

The debate over the 2016 ballot initiative in California offers a helpful reminder that although the definition of “violence” is often taken to be self-evident, the category can be surprisingly difficult to delineate. It highlights, too, the importance of underlying, often unarticulated ideas about the nature of violence—in particular, ideas about whether violence is situational or dispositional. Both supporters and opponents of Proposition 57 frequently elided the distinction between violent offenders and persons convicted of violent offenses. That distinction matters greatly if violence is understood to be situational, but less so if violence is thought to be a property of people and not just of acts. Most of all, though, the debate underscored the broad acceptance of the idea that lenience can be appropriate for nonviolent offenders, but not for the violent.

That idea continues to have great power. In recent years, for example, many states have restored voting rights to people who have completed prison sentences for felonies, but generally only if the felonies were nonviolent. In 2019, Senator Bernie Sanders, campaigning to be the presidential nominee of the Democratic Party, called for restoring voting rights to all former prisoners; he was immediately criticized for including people convicted of violent offenses. Two months later, Mayor Bill de Blasio of New York City took a break from his own presidential campaign to criticize the Brooklyn district attorney’s office for allowing some young offenders charged with illegal gun possession to avoid jail time and a criminal record by successfully completing a yearlong diversion program. De Blasio called diversion “a valid tool,” but only “for nonviolent offenses.” Back in California, Jerry Brown was followed as governor by Gavin Newsom, who campaigned on a platform pledging criminal justice reform and reduced levels of incarceration. But in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic of 2020, with advocates warning that the contagion would spread explosively in the state’s overcrowded prisons, Newsom drew a sharp line: “I have no interest,” he explained, “and I want to make this crystal clear, in releasing violent prisoners from our system.” Faced with similar calls to release prisoners to slow the spread of the virus, officials in other states made the same distinction, as did the United States Department of Justice. The result was that prison populations declined only negligibly, by 1.6 percent, during the first three months of 2020, as the pandemic spread. (Prisons soon became the sites of the worst outbreaks of the virus. By October 2020 more than 150,000 prisoners had contracted the disease, and over 1,200 had died from it.)5

For decades, it has been common ground in debates about criminal justice that violent crimes are the most serious crimes, the crimes that deserve the harshest penalties. Even critics of the critics of our current punishment practices—people who think the reformers don’t go far enough—tend to share that view. Over the last decade, many reformers have begun to push, with some success, for elimination of some of the barriers placed in the path of formerly incarcerated people seeking education or employment. Predictably, the reform efforts have focused on helping those with convictions for nonviolent offenses. That restriction has been criticized. But the criticism, when it is offered, is usually that even violent offenders deserve a second chance. It is rare for anyone to question the underlying idea that violent offenders are the worst offenders—the scariest, the most culpable, the least deserving of mercy.6

Violence, Infamy, and Moral Turpitude

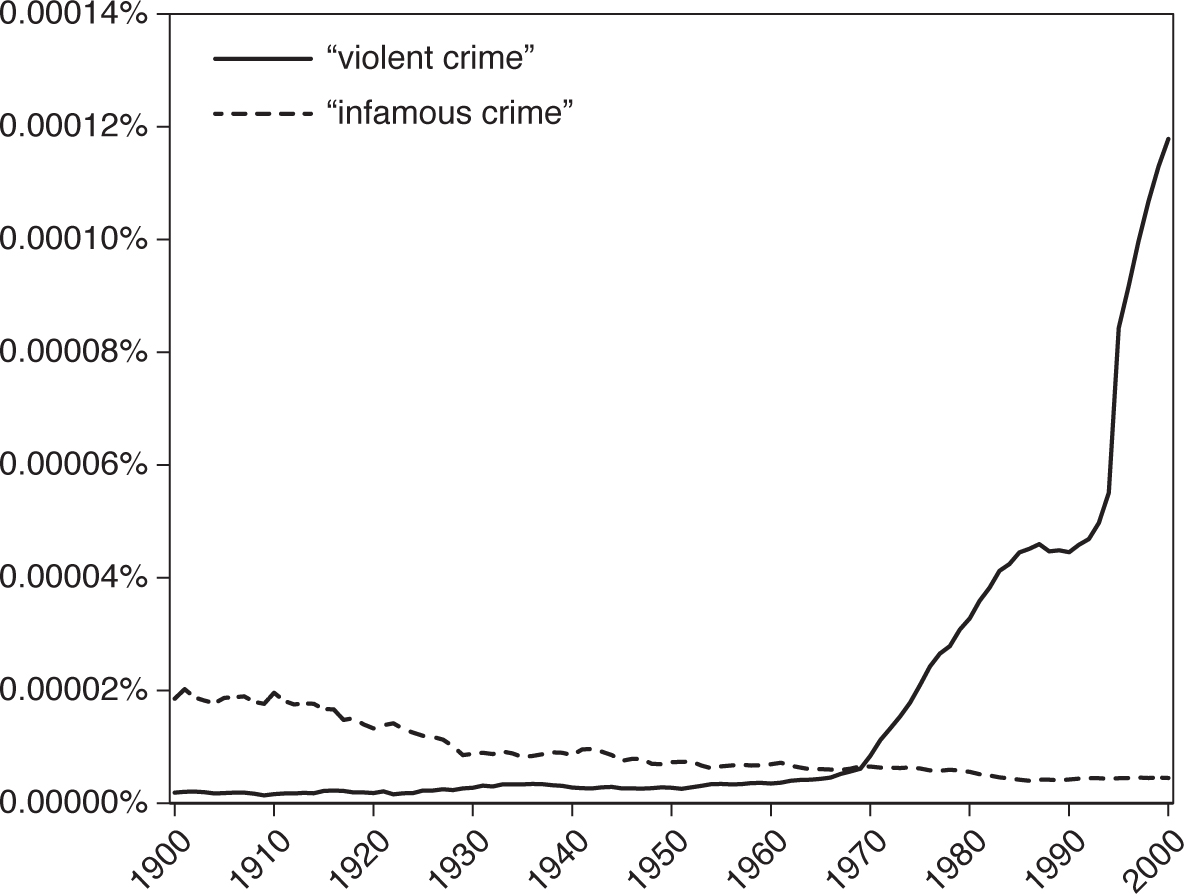

The distinction between violent and nonviolent crimes is so widespread today in legal codes and debates about the law that it can seem utterly natural. Scholars, legislators, and reformers all tend to treat it as obvious that violent crimes are the most serious and deserve the heaviest penalties. Violent criminals, we think, are why we have prisons; they are what criminal law and criminal punishments are designed, above all, to address.7 But the sharp distinction between violent and nonviolent crimes, and the great weight placed on that distinction, are modern developments, roughly half a century old. As Figure 1 suggests, references to “violent crime” did not become common in American discourse until the 1970s. Before the late 1960s, in fact, references to “violent crime” were less common than references to “infamous crime”—a legal category that, as we will see, was itself never terribly important, and that in no way tracked the line now drawn between violent and nonviolent offenses.8

If you peruse, say, the discussion of criminal law in William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England—by far the most widely read legal treatise in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century America—you find few references to violence, and the references you do find cut both ways. Occasionally “violence” is seen as making a crime more serious. Blackstone defines robbery as “open and violent larceny from the person,” and he explains that “violence, or putting in fear, is the criterion that distinguishes robbery from other larcenies” and makes it “more atrocious than privately stealing.” But Blackstone is just as apt to use the term “violence” to refer to emotions instead of acts, and “violence” of that kind is an extenuating rather than an aggravating factor. Thus, Blackstone notes that “the violence of passion, or temptation, may sometimes alleviate a crime.” For example, “to kill a man upon sudden and violent resentment, is less penal than upon cool, deliberate malice.” As late as 1935 the American legal scholar Karl Llewellyn thought it obvious that theft, not violence, was “the heart of the really criminal Criminal Law.”9

FIG. 1 Frequency of references to “violent crime” in books published in the United States, 1900–2000, compared with references to “infamous crime.” The vertical axis measures the occurrences of each phrase as a proportion of all two-word sequences. The lines show seven-year trailing averages. (Data source: Google Books Ngram Viewer.)

Historically, the most important distinction drawn among offenses in Anglo-American law has not been between violent and property offenses, or between infamous and non-infamous crimes, but between felonies and misdemeanors. This is a very old distinction, dating back perhaps to the twelfth or thirteenth century. Well before the eighteenth century the distinction between felonies and misdemeanors had come to be understood as the distinction between more heinous and less heinous offenses, although treason originally was in a special class by itself, even more heinous than felonies, and sometimes the word “crime” was used to refer collectively to treason and to felonies—hence the references, which used to be common, to “crimes and misdemeanors.” Blackstone said that treason was “strictly speaking” a felony, because it met the ancient criterion: it was a crime for which the offender’s life and property could be forfeited to the Crown. Later on felonies became, more or less, crimes for which an offender could be executed. Still later, in the United States, felonies were crimes punishable by death or by a term of incarceration in a state prison, which typically meant crimes punishable by a term of a year of more.10

By the late nineteenth century, if not earlier, complaints were voiced that the distinction between felonies and misdemeanors was “antiquated and unmeaning,” and Great Britain abandoned the distinction in 1967. But the United States has continued to classify crimes as felonies or misdemeanors. The Supreme Court has called this distinction “minor,” “highly technical,” and “often arbitrary,” but it remains the most pervasive way that American law distinguishes between more serious and less serious offenses.11

The number of crimes classified as felonies has grown dramatically over the centuries, certainly in absolute numbers and possibly also as a proportion of all crimes. Moreover, the precise set of crimes defined as felonies varies from state to state. But “felony” has never meant “violent crime.” There have always been nonviolent crimes treated as felonies, and there have always been violent crimes treated as misdemeanors. The original, “common law” felonies, defined not by statute but by judicial decisions, included murder, manslaughter, rape, robbery, and “mayhem” (which meant, roughly, any intentional and disabling maiming). But the list also included arson, burglary, larceny, and sodomy. Assault was not originally a felony—not even assault with a deadly weapon, or assault with intent to kill. Even today, most assaults are misdemeanors rather than felonies.12

The law has distinguished among felonies in various ways at various times, but until recently—until, roughly, the last half century—none of these distinctions amounted to separating violent from nonviolent crimes. For example, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century law, both in England and in some of the American colonies, made some felonies but not others eligible for “benefit of clergy,” which was a roundabout use of a legal fiction to spare convicted defendants from the death penalty. Originally, benefit of clergy was an actual benefit for actual clergy: it was a rule allowing priests and monks accused of crimes to transfer their cases to ecclesiastical courts. By the seventeenth century, though, the rule had been changed to call for a substitution of lesser punishment, not a transfer to ecclesiastical courts, and it could be invoked by anyone who could read; by the eighteenth century it applied to the illiterate as well. Violent offenses could be “clergyable,” and some nonviolent offenses, at least originally, were not. For example, all aggravated forms of theft, including larceny from a dwelling house and larceny of property worth more than a certain amount, were initially exempted from benefit of clergy.13

Anglo-American law also distinguished for centuries—and for some purposes, in some places, still distinguishes—between “infamous” crimes and other, lesser offenses. The common-law judges declared anyone who had been convicted of an “infamous” crime incompetent to testify as a witness, and the category gradually became meaningful for other purposes as well. The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, for example, requires a charge from a grand jury before anyone is tried for a capital “or otherwise infamous” crime. In many states, conviction for an infamous crime was held to be grounds for divorce. “Infamous” never meant “violent.” The infamous crimes that made a witness incompetent at common law included not just all felonies but all “crimen falsi”: crimes involving fraud or misrepresentation. Later, “infamous crimes” came to be understood as crimes punishable by incarceration in a state prison or other stigmatizing penalties, such as hard labor or the loss of the right to vote and to run for office. This has meant that, for the most part, the category of infamous crimes largely tracks the category of felonies.14

Yet another distinction drawn by American law, since the early nineteenth century, is between crimes that involve “moral turpitude” and those that do not. The “moral turpitude” standard was initially used to identify “slander per se”: statements so obviously harmful to reputation that a plaintiff suing for defamation would not need to offer proof of damages. Beginning in the early 1800s, American courts limited the category of slander per se to accusations that, if true, would make out either “a crime of moral turpitude” or a crime carrying “an infamous punishment.” Later the standard of “moral turpitude” was exported to evidence law, where it determined which crimes could be used to impeach the credibility of a witness; to immigration law, where it controlled which misdemeanor convictions would bar an immigrant from entering the United States or justify deportation; and to rules of professional licensing, voter eligibility, and juror selection, where it governed which criminal convictions were disqualifying. Federal evidence law, and the evidence codes of most states, have now abandoned the “moral turpitude” standard for regulating the impeachment of witnesses, but California and Texas still use the standard for those purposes, and crimes involving “moral turpitude” still have special status in defamation law, immigration law, rules of professional licensing, and rules of voter and juror eligibility.15

The standard even shows up in some employment contracts. In 2011, when Warner Brothers fired the television actor Charlie Sheen from his lead role in the situation comedy Two and a Half Men, the studio justified its action in part based on a contractual provision allowing it to deem Sheen in default if it reasonably believed that (a) he had committed “a felony offense involving moral turpitude,” and (b) the conduct interfered with his ability to carry out his side of the agreement. Warner Brothers said this provision had been triggered by Sheen’s “furnishing of cocaine to others as part of [his] self-destructive lifestyle.”16

In none of these contexts—defamation, evidence, immigration, licensing, or voter and juror eligibility—have crimes of “moral turpitude” ever been equated, even loosely, with crimes of violence. On the contrary, courts have repeatedly said that violent offenses do not necessarily involve moral turpitude, whereas almost all crimes involving fraud or sexual misconduct do fall within the category.17 In determining whether a crime that doesn’t involve fraud or sexual misconduct nonetheless shows moral turpitude, courts have sometimes asked whether the crime is malum in se rather than malum prohibitum—that is, whether it involves conduct that would be wrongful even if it were not legally prohibited—or whether it requires scienter, a level of conscious intent. They have never asked whether it was violent.

In fact, there is a long history of courts refusing to treat violent offenses as crimes of moral turpitude. Moral turpitude has typically been defined as “conduct that is inherently base, vile, or depraved,” and courts have been clear that violence, even homicide, is not necessarily that kind of conduct. Law professor Julia Simon-Kerr, who has studied the history of the moral turpitude standard, points to an illustrative nineteenth-century decision by the Iowa Supreme Court reasoning that it was slander per se to say that someone had poisoned a neighbor’s cow, even though an accusation of homicide would not have been slander per se. “Homicide may be committed in the heat of sudden passion,” the court explained, “… but no circumstances can possibly extenuate the moral turpitude of that wretch who will poison his neighbor’s horse or cow.”18

Simon-Kerr notes that decisions of this kind were especially common in the nineteenth century, and she traces them to the gendered honor codes from which courts in that century drew the term and the concept of “moral turpitude.” But throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century, crimes of dishonesty or sexual misconduct were, and remain, more likely to be treated as involving moral turpitude than crimes of violence. In 1926, for example, a federal judge in Massachusetts blocked the deportation of a noncitizen who had attacked a police officer with a razor, reasoning that the crime of conviction, assault and battery of a police officer, did not necessarily involve moral turpitude. “If one ordinarily law-abiding, in the heat of anger, strikes another,” the judge explained, “that act would not reveal such inherent baseness or depravity as to suggest the idea of moral turpitude.” Relying in part on the authority of that decision, courts today continue to hold that simple assault, or even “aggravated assault where the defendant knows that the person he is assaulting is a law enforcement officer and causes bodily injury,” is not a crime of moral turpitude for immigration purposes.19

Codes and Classifications

The categories of felonies, misdemeanors, infamous crimes, and crimes of moral turpitude all emerged from common-law adjudication: the gradual, case-by-case accumulation of judicial decisions that then served as precedents for later decisions. But since the eighteenth century there have been repeated attempts, some more successful than others, to codify and systematize the criminal law, both in England and later in the United States. Each of these efforts grappled with the question of how best to categorize crimes—what made some kinds of offenses more serious, or deserving of greater punishment. It is striking that until recently none of these schemes placed much, if any, weight on the distinction between violent and nonviolent crimes.20

The point of departure for many of these efforts to codify and classify criminal prohibitions was Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws, widely influential in England and in the American colonies. Montesquieu divided crimes into four classes, depending on whether they ran “counter to religion … to mores … to tranquility … [or] to the security of the citizens.” The fourth category included physical attacks, like intentional killings, but also violations of “security with respect to goods.” In general, Montesquieu thought the penalty for a crime should “be drawn from the nature of the thing,” so the death penalty was the proper sanction for homicide, and violations of “security with respect to goods” should preferably be punished with fines or other deprivations of property. But because fines might not deter those of little means, Montesquieu concluded that “the corporal penalty has to replace the pecuniary penalty,” even for property offenses. He drew no sharp line—no explicit distinction at all, really—between violent and nonviolent crimes.21

Neither did Jeremy Bentham, writing a few decades later. Bentham’s classification scheme divided crimes into five categories: (1) “PRIVATE offences, or offences against assignable individuals”; (2) “SEMI-PUBLIC offences, or offences affecting a whole subordinate class of persons”; (3) “SELF-REGARDING offences: offences against one’s self”; (4) “PUBLIC offences, or offences against the state in general”; and (5) “MULTIFORM or ANOMALOUS offences; … containing offences by FALSEHOOD, and offences concerning TRUST.” It did not occur to Bentham, as it did not occur to Montesquieu, to treat violent crime as a separate, especially serious category.22

Nor did it occur to any of the major codifiers of Anglo-American criminal law: Edward Livingston, who submitted a proposed penal code for Louisiana in 1826; Thomas Macaulay, drafter of the proposed Indian Penal Code of 1837; David Dudley Field and his collaborators, who completed their proposed penal code for New York in 1865; James FitzJames Stephen, who in 1878 made the first serious effort to codify English criminal law; or Herbert Wechsler, architect of the Model Penal Code, which was finalized in 1962. Livingston, for example, sorted crimes into twenty-one categories: fifteen categories of “public offenses which principally affect the state or its government,” and six categories of “private offenses which principally affect individuals.” One of the latter six categories—“offenses affecting the persons of individuals”—included homicide, rape, assault, abduction, and false imprisonment, but it also included abortion, and it excluded robbery, whether armed or unarmed. Robbery was grouped with arson, burglary, theft, and fraud; these were all categorized as “offenses against private property.” Rioting—assembling “with intent to aid each other by violence” either to commit an offense or to violate rights—was classified as a “public offense” and placed in the category of “crimes against public tranquility,” a category that also included nonviolent “public disturbances.” Livingston’s code did not separate out violent crimes.23

Neither did the prominent codes that came afterward. Macaulay’s Indian Penal Code classified homicide, rape, assault, abduction, and wrongful confinement as “offenses affecting the human body,” a category that also included abortion and any touching of a person or an animal “to gratify unnatural lust.” Like Livingston, Macaulay treated robberies as “offences against property” and riots as “offences against the public tranquility.” New York’s Field Code classified riots (along with unlawful assemblies and prize fights) as “crimes against the public peace”; treated homicides, suicides, maimings, robberies, kidnappings, assaults, and duels (along with libels) as “crimes against the person”; and cataloged rapes (along with abortion, child abandonment, bigamy, indecent exposure, and lotteries) as “crimes against the person and against public decency and good morals.” Stephen’s proposed codification of English criminal law grouped riots together with unlawful assemblies, duels, prize fights, and breaches of the peace; Stephen categorized homicide, assault, rape, abortion, bigamy, child neglect, and defamation as “offenses against the person and reputation”; and he put robbery and burglary, along with theft, fraud, forgery, counterfeiting, arson, and vandalism, under the heading “offenses against rights of property or rights arising out of contracts.”24

These were the prior efforts at codification that the criminal law scholar Herbert Wechsler and his collaborators drew upon when they compiled the Model Penal Code for the American Law Institute (ALI) in the mid-twentieth century. This massive project began in the early 1950s and reached fruition in 1962, when the ALI formally adopted Wechsler’s Code. The Model Penal Code groups felonies into three groups according to their perceived seriousness: first degree, second degree, and third degree. First-degree felonies are supposed to incur the heaviest penalties; third-degree felonies are to be punished the least severely. Violent crimes are distributed throughout these three categories: some forms of aggravated assault, for example, are treated as third-degree felonies, and so are “terroristic threats.” Some nonviolent offenses, on the other hand, are categorized as second-degree felonies. These include forgery, arson, abortion, and aggravated forms of burglary.

The Model Penal Code does, however, limit the category of first-degree felonies to violent offenses—at least if robbery is treated as a violent offense, and not, as earlier codifiers typically suggested, as an offense against property. And robbery is a first-degree felony under the Model Penal Code only if the robber tries to kill someone or to cause serious bodily harm. So we can see in the Model Penal Code the beginnings, but only the beginnings, of the idea that later came to seem obvious to scholars and reformers: that violent crimes were the most serious crimes and the crimes that, generally speaking, should trigger the harshest penalties.25

The first federal criminal statute referring explicitly to “violent crimes” or “crimes of violence” appears to have been enacted in 1961—the year before the promulgation of the Model Penal Code. For the next twenty years, there was exactly one such reference in all of the federal criminal code. Ten more federal criminal statutes referring to “violent crimes” or “crimes of violence” were added in 1994. By 1996 there were twenty such statutes, and a decade later there were twenty-eight. Today so many federal statutes use the phrase “crime of violence,” and employ similar definitions of the term, that the Supreme Court has declared that failing to interpret the phrase consistently “would make a hash of the federal criminal code.”26

From There to Here

As early as 1978 the journalist Charles Silberman could claim without fear of contradiction that few social problems were as important, as permanent, or as inflammatory as violent crime. “All over the United States,” he observed, “people worry about criminal violence.” By 1994, President Bill Clinton was warning in his State of the Union Address that “violent crime and the fear that it provokes are crippling our society” and “fraying the ties that bind us.” Not crime in general: violent crime. The omnibus federal crime law enacted that year was called the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act; among other things, it required any state seeking federal funding for prison construction to prove that it had increased both the percentage of violent offenders sentenced to prison and the average time they spent in prison. By 2007 the legal scholar Jonathan Simon was arguing that the United States had “built a new civil and political order structured around the problem of violent crime.” Simon thought the country had come to be “governed through crime,” that crime was “legitimizing” and “providing context for the exercise of power.”27

Simon could take for granted in 2007 that his readers would understand that “crime” in this context meant “violent crime.” Writing four years later, law professor Alice Ristroph noted that “from the general public to the specialists, everyone seems to think of crime in terms of violence”; everyone seems to believe that “the primary reason to have criminal laws, police forces, and prisons is to address the problem of violent crime.” Incarceration, says the criminal justice reformer Danielle Sered, owes its standing in society largely to “its role in protecting people from violence and those who commit it.” But how did violence come to be understood as the crux of the crime problem? How did violent crime become a synonym for serious crime?28

Part of the answer is that violent crime ballooned in the 1960s and 1970s. Between 1960 and 1980 the annual murder rate doubled in the United States, from 5 per 100,000 people to 10 per 100,000 people. The “violent crime rate” computed each year by the Federal Bureau of Investigation—a figure that adds together murders, rapes, robberies, and aggravated assaults—more than tripled, rising from 161 per 100,000 in 1960 to 597 in 1980. The increases in major cities were even steeper. The annual murder rate in New York City went from 5 per 100,000 in 1960 to 26 per 100,000 in 1980; in Detroit during the same period the figure rose from 9 to 46. One reason people worried more about violent crime in 1980 than in 1960 was that there was more violent crime to worry about.29

But that explanation has limited power. To begin with, crime in general increased in the 1960s and 1970s, and the increases in nonviolent crime were, if anything, sharper than the increases in violent offending. Figure 2 tracks annual rates of violent crime and property crime in the United States from 1960 through 2014. Both sets of numbers come from the Uniform Crime Reports compiled by the FBI. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, property crime—combining burglary, larceny, and vehicle theft—rose virtually in lockstep with violent crime.

It was not until the late 1980s that violent crime began to rise more sharply than property crime, and even that divergence may be a statistical artifact. The Uniform Crime Reports rely on data submitted by local police departments, and those numbers suffer from well-known deficiencies: many crimes are never reported to the police, and when a crime is reported, the police often exercise discretion in whether and how to record it. The two kinds of crimes for which the UCR statistics are probably most reliable are murder and vehicle theft: murder because deaths are hard to overlook, and vehicle theft because insurance companies will not reimburse for a stolen car unless the policyholder files a police report.30 Figure 3 tracks annual changes in the rates of murder and vehicle theft from 1960 to 2014, drawing on the UCR statistics compiled by the FBI. Again, the figures rise pretty much in unison in the 1960s and 1970s. The trends begin to diverge in the mid-1980s, but that is because at that point vehicle theft starts to rise more rapidly than homicide, not the other way around.

By historical standards, the crime increase in the 1960s was unusually steep, and it lasted unusually long. But it wasn’t the first time that crime, including violent crime, had risen steeply in American cities. It may have been the first time, though, that violent crime was singled out as an issue of special concern. Homicides spiked in New York City and in Boston in the decades leading up to the Civil War, for example, but violent crime never became, then, the kind of issue that it became in the last part of the twentieth century, and the kind of issue that it remains to this day. Crime and disorder were major issues in the nineteenth century; there were arguments in Massachusetts, for example, that Boston should cede some of its municipal autonomy, given the city’s failure to control its “dangerous classes.” But according to Roger Lane, a pioneering historian of crime and policing in America, “mob action was the only form of violence which generally figured in these complaints, and ‘crime’ was used typically as a synonym for vice.” Lane points out that in this period “the laws concerning drink … were subject to constant revision, but except for a reduction in the number of cases involving the death penalty, the general criminal code was not.” He concludes that “as the sons and daughters of Massachusetts migrated to the metropolis, the image conjured by the fearful was the rake or the tempter, not the robber or rapist.” Well into the twentieth century, vice—not violence—was the most common synecdoche for urban crime, in Massachusetts and elsewhere in the United States.31

FIG. 2 Property crime and violent crime rates in the United States, 1960–2014. (Data source: Uniform Crime Reporting Statistics compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.)

FIG. 3 Murder and vehicle theft rates in the United States, 1960–2014. (Data source: Uniform Crime Reporting Statistics compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.)

So crime trends in the 1960s and 1970s do not, by themselves, explain the focus on violent crime that has come to seem natural in criminal law over the past half century. Other factors were at work. One, perhaps, was a global, centuries-long decline in violence, fueled by and in turn reinforcing a gradual change in sensibilities—the “civilizing process” described by the twentieth-century German sociologist Norbert Elias. Steven Pinker’s long 2011 book about violence argued that violence has gradually declined for centuries around the world, albeit unevenly and in fits and starts. Pinker credited not just changes in manners, which were Elias’s focus, but also widening compassion and the increased application of reason: the Enlightenment writ large.32

The rise in violent crime in the 1960s and 1970s—a trend seen throughout the West but especially pronounced in the United States—represented a kind of backsliding. It may have been particularly alarming precisely for that reason. Roger Lane, writing in the late 1960s, concluded that “heightening … standards of propriety” had sharply reduced serious crime since the nineteenth century, but that the process did not proceed without interruption. “There are times,” he noted, “when for various reasons the level of violence overbalances current expectations,” and “in such situations the social pressure to maintain and extend high standards, and to enforce them universally, may result in frustration,” and “the frustration may translate into fear.”33 Charles Silberman offered much the same diagnosis a decade later:

For people over the age of thirty-five … the upsurge in crime that began in the early 1960s appeared to be a radical departure from the norm, a departure that shattered their expectations of what urban and suburban life was like. The trauma was exacerbated by the growing sense that the whole world was getting out of joint, for the explosive increase in crime was accompanied by a number of other disorienting social changes—for example, a general decline in civility, in deference to authority, and in religious and patriotic observance.34

Silberman wasn’t alone in connecting concerns about crime in the 1960s and 1970s with concerns about “other disorienting social changes.” And we can go further. Rising concerns about violent crime in the late twentieth century may have been fueled, in part, by a whole series of historical developments that made violence seem more frightening—official as well as unlawful violence, overseas as well as domestic violence. Those developments included, but were hardly limited to (1) the massive casualties of the first and second world wars; (2) the rise of modern totalitarianism, and the horrific uses of violence by Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia; (3) the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the later assassinations of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Senator Robert Kennedy, and the still later attempts on the lives of President Gerald Ford and President Ronald Reagan; (4) the urban riots of the late 1960s; (5) the televised carnage of the Vietnam War, and the revelation of the massacre by American troops at My Lai; (6) the wave of bombings, abductions, armed robberies, and murders carried out by radical groups in the United States and Europe; (7) the police riot outside the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago and the fatal shootings of student protesters by National Guard troops at Kent State two years later; (8) the gruesome murders by Charles Manson and his “family,” and the connection those crimes seemed to have with the counterculture and with a general social unraveling; and (9) the wave of riots and violent uprisings in prisons across the country in the early 1970s.35

All of these developments contributed to a sense that the twentieth century had taken bloodshed to unprecedented levels, and that—in the words of psychiatrist James Gilligan—Americans were witnessing “a continuing and ever-accelerating escalation of the scale of human violence.” That wasn’t the consensus view of historians, then or now, but it was and remains a widespread view. It may well have contributed both to an increased revulsion from violence and to the growing salience of violence in criminal law.36 Following the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy in 1968, President Johnson appointed a National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence—which carried out its work in the wake of other presidential commissions, all appointed between the years of 1965 and 1967, on (1) Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice, (2) Civil Disorders, and (3) Crime in the District of Columbia. In 1970, following the fatal shootings of student demonstrators by National Guard troops at Kent State, President Nixon established yet another presidential commission, this one focused on “campus unrest.”

The growing importance of violence in criminal law may have owed something not just to increasing concerns about violence but also to rising interest in nonviolence as a political method and a moral principle. That increased interest was itself a reaction, in part, to the appalling turns that violence took in the twentieth century, but it owed a great deal as well to the celebrated campaigns of civil disobedience led in colonial India by Mahatma Gandhi and then in the American South by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The strikes and boycotts organized by the United Farm Workers further burnished the luster of nonviolence for many Americans, particularly on the left. By the 1970s, nonviolent protest had become part of the American civic religion; pictures of Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, and Delores Huerta went up alongside George Washington and Harriet Tubman in many public school classrooms. Despite the turn toward violence at many protests in the Trump era, the strategic and moral superiority of nonviolence remained utterly obvious to many activists in the United States. Following “Antifa” attacks on right-wing protesters in Berkeley in 2017, a liberal activist expressed bewilderment. “We’re just puzzled,” she told a reporter, “as to why people consider violence a valid tactic.” Five years later, when police killings sparked protests and lootings across the United States, a city council member in Louisville, supportive of police reform, warned that “we have to be careful to control our message, and violence changes that message.” Even a former New Left radical like Mark Rudd, active in the Weather Underground in the late 1960s and early 1970s, now calls nonviolence “the one essential strategy to achieve positive social change.”37

By the mid-1990s, when mass incarceration started to become a priority issue for criminal justice reformers, it seemed natural to focus on “nonviolent” drug offenders. Nonviolent offenses were the least serious, and nonviolent offenders were the least threatening. Writing in 2010, James Forman Jr. lamented that “since it is especially difficult to suspend moral judgment when the discussion turns to violent crime, progressives tend to avoid or change the subject.” Forman warned that targeting reform efforts at nonviolent offenders did not just respond to prevalent ideas about the relative severity of offenses; it reinforced those ideas. The more that reformers highlighted the plight of nonviolent offenders, the more they argued that people who hadn’t been violent deserved leniency, the more they suggested by implication that people who had been convicted of violent offenses didn’t deserve leniency.38

Rising rates of violent crime, growing revulsion from violence, the veneration of nonviolent protest, and the tactics of criminal justice reformers may all have contributed to the increasing significance of violence in criminal law over the past half century. But it is impossible to understand this or any other development in American criminal justice without taking account of race. The rise in violent crime in the 1960s and 1970s was disproportionately a rise in urban crime, and the rise in urban crime was disproportionately a rise in crimes committed by African Americans. It was also disproportionately a rise in crimes committed against African Americans; most violent crime, then as now, was intra-racial. But it was the disproportionate representation of Blacks among offenders, not the disproportionate victimization of Blacks, that became a critical part of the politics of crime in the late twentieth century. “Violent crime rates in the nation’s biggest cities,” notes the historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad, have come to be “generally understood as a reflection of the presence and behavior of the Black men, women, and children who live there.” That understanding, combined with the association of violence with masculinity, and the pervasive focus on violent crime as the kind of crime most worth worrying about, explains why law professor Paul Butler can argue plausibly that “American criminal justice today is premised on controlling African American men.”39

There is reason to suspect that the association of violent crime with Blackness has influenced the theories that the law has come to embody about how violence operates: the racialization of violent crime has likely had more than a little to do with the increasing tendency to understand criminal violence as a product of offenders’ characters, not of the situations in which they find themselves. We will return to this connection later in the chapter. For now, I want to note that the racial tilt in patterns of offending—and, more importantly, in popular understandings of offending—may have played a role not just in legal theories about the nature of violence but also in the growing significance of violence in criminal law.

The nature of that role isn’t completely clear. The tendency of white Americans to associate Blacks with criminality dates back to the nineteenth century, but Muhammad’s work suggests that the racial tropes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries emphasized the supposed immorality, dissolution, and sexual rapaciousness of African Americans as much as or more than any across-the-board tendency toward violence.40 With one arguable exception, discussions of Black criminality in the early twentieth century—like discussions then of crime more generally—appear to have focused more on vice than on violence.

The exception was the fear of Black men sexually assaulting white women—a terror, an obsession, and a rage that helped drive the campaign of terror that lynch mobs waged against African Americans from the end of the Civil War well into the twentieth century. Roughly a quarter of the more than 4,000 African Americans murdered in lynchings during the Jim Crow era—from 1880 through 1940—were accused of sexual assault, but “assault” here must be understood loosely. The Equal Justice Initiative, which has been working to inventory and document America’s legacy of lynchings, notes that “the definition of black-on-white ‘rape’ in the South was incredibly broad and required no allegation of force,” because “white institutions … and most white people rejected the idea that a white woman could or would willingly consent to sex with an African American man.” African American men were lynched for merely coming into contact with, writing to, or “associating with” white women. (This was true as well in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. The Equal Justice Initiative concludes that at least 2,000 African Americans were lynched from 1865 through 1877, many of them men accused of seeking romantic or sexual intimacy with white women.) Roughly 30 percent of lynching victims in the Jim Crow South were accused of murder, but hundreds, if not thousands, of African Americans were lynched before and during Jim Crow based on accusations of far less serious crimes, including vagrancy, or social transgressions such as “speaking disrespectfully, refusing to step off the sidewalk, using profane language, using an improper title for a white person, suing a white man, arguing with a white man, bumping into a white woman, [or] insulting a white person.”41 As an institution, lynching was not chiefly a response to violence; it was a deployment of violence—deadly, horrific violence—to enforce a social code. The constellation of Black transgressions, real and imagined, that loomed large in white minds in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries included, but was not centered around, violent crime.

Nonetheless, when crime rates began to soar in the 1960s and 1970s, the concentration of violent crimes in heavily Black, urban neighborhoods may have made those crimes especially frightening to white Americans, and may therefore have contributed to the rising salience of violence in criminal law. That dynamic may have been fueled by specific, psychological pathways of racial prejudice. For example, white Americans have long associated Blacks with animals, and more particularly with apes—sometimes consciously and sometimes unconsciously. Those associations remain strong today; they show up explicitly in racist tweets and implicitly in unconscious processes studied by psychologists and media scholars. It therefore seemed all the more natural in the 1960s and 1970s to refer to America’s increasingly violent urban neighborhoods as “jungles” and to urban criminals as “animals.” That imagery, in turn, helped to make violence increasingly central to the American understanding of criminality. The peril of the jungle is not indolence or immorality, but “Nature, red in tooth and claw.”42

The War on Drugs and Its Aftermath

The increasing significance of violence in criminal law may have yet another cause: it may be, in part, a lingering reaction to the late twentieth-century “war on drugs.” After staying stable for decades, incarceration rates in America began to climb in the 1980s, and a large part of the explanation was new, tougher sentences for drug crimes. Historically, drug policies in the United States have gone back and forth between laxity and harshness, and during the Reagan era the pendulum swung very far in the direction of harshness. Statutes mandating long sentences for narcotics offenders were adopted at both the federal and the state level. The federal sentences, required by a statute enacted in 1986, were especially draconian, and they had an especially disproportionate impact on minority defendants. The new federal drug sentences were adopted at the same time that the federal government was implementing a new regime of presumptive sentencing guidelines that heavily restricted the discretion of sentencing judges, and those guidelines wound up following the lead of, and extending the reach of, the mandatory minimum sentences prescribed by the 1986 drug law.43

By the early 1990s there was a growing sense among many Americans that the war on drugs had gone too far: that too many people, especially people of color, were being locked up on drug charges for too long. At the same time, politicians were feeling ever-escalating pressure to appear “tough on crime.” Democrats had watched Richard Nixon win the presidency in 1968 and 1972 as the candidate of “law and order.” They saw George H. W. Bush defeat Michael Dukakis in 1988 by highlighting Dukakis’s opposition to the death penalty and his furloughing of a convicted African American murderer, William Horton, who had then absconded, kidnapped a man and a woman, stabbed the man, and raped the woman. In a now-infamous television ad, a political action committee with ties to the Bush campaign showed pictures of Horton, renamed him “Willie,” and described the crimes he committed after escaping while on a “weekend pass.” The lesson Democrats learned was that they could call for moderation of drug punishments but they could not allow themselves to be out-toughed on “violent crime.”44 The Democratic Party platform in 1992 called for fighting drug addiction with counseling, treatment, and education. It also singled out the rise of “violent crimes” as an “alarming” threat to America’s communities and called for “put[ting] more police on the streets” to restore “law and order” in “crime-ravaged communities.” Arkansas governor Bill Clinton, who won the Democratic nomination and the presidency in 1992, established his credentials early on the issue of violent crime: in January 1992 Clinton took a break from campaigning in New Hampshire and flew home to oversee the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a convicted murderer so intellectually disabled he asked to save the dessert from his last meal “for later.” Two years after Clinton’s election, Congress passed the largest crime bill in American history; it was titled the “Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994” and contained, among other things, funding for 100,000 new police officers.45

Clinton’s successful campaign for the presidency in 1992 encapsulated what became the center-left position on criminal justice throughout the 1990s and early 2000s: de-escalate the war on drugs, but give no quarter to violent crime. Politicians and activists opposed to harsh drug sentences almost always talked about “nonviolent” drug offenses; they took care not to call for leniency for violent offenders. This was true of policymakers as well. A 1994 report by the US Department of Justice reconsidered the treatment of “low-level drug law violators,” by which the Department meant nonviolent drug offenders with little or no criminal history.46

That was also the population targeted by drug courts, the cornerstone of liberal efforts to reform drug prosecutions in the 1990s. Drug courts divert offenders from prison and send them instead into treatment programs; typically the threat of a prison sentence hangs over the defendant’s head until the treatment program is successfully completed. The first drug treatment court opened in Miami in 1999, and the idea quickly spread across the country, becoming “the generic policy response of choice to dissatisfaction with the war on drugs.” From the start, drug courts largely excluded violent offenders: not just defendants currently facing a charge of a violent crime, but also defendants who had been convicted of a violent crime at any point in the past. The 1994 crime bill provided federal funding for drug courts, but mandated the exclusion of any defendant with a current or prior violent offense. By the end of the 1990s, many drug courts had loosened their eligibility criteria, but the vast majority continued to exclude defendants with current or prior convictions for any violent crime.47

Drug courts soon provided the template for other kinds of “therapeutic” or “problem-solving” courts, all of which aim to divert certain classes of offenders from prison, as long as they attend and successfully complete treatment programs. Many states now have “mental health courts” and “veterans courts.” These programs, too, often exclude violent offenders. This is true even of veterans courts, despite the fact that a large share of the cases that bring veterans into court involve assaults or hit-and-run collisions. In the words of one advocate, excluding violent offenders can mean having “a Veterans Court without veterans.” Nonetheless, most veterans courts “focus on non-violent crimes”; some address “low-level domestic violence charges,” but that has proven controversial. Kamala Harris, then district attorney of San Francisco, championed diversion courts but not for violent offenders. “Violent offenders,” she explained, “have crossed a line that reduces our confidence that we can redirect them.” And, as we have seen, Mayor Bill de Blasio of New York City argued as recently as 2019 that diversion programs were a good idea, but only for nonviolent offenses.48

Therapeutic courts began to spread across the country at exactly the same time that states and the federal government were adopting new, extraordinarily harsh penalties for violent crime. The most important of these penalties were contained in a wave of “Three Strikes” laws, statutes that mandated long sentences for repeat offenders. These laws sought to put those offenders on notice that “three strikes and you’re out,” and they zeroed in, generally, on repeat violent offenders. Laws authorizing or requiring stiffer sentences for recidivists have a long history, but until the early 1990s these statutes did not use the language of baseball, and—what matters more—they did not focus on violent offenses, or on any other category of crime deemed especially serious.49 Since their inception, Three Strikes laws have taken aim at violent crime. Sometimes the target offenses have also included narcotics trafficking and / or sex offenses, but violent offenses have always been at the core, not just in the coverage of the statutes but in the rhetoric supporting their adoption.

The first Three Strikes law was adopted in the state of Washington by voter initiative in 1993. It required a life sentence for anyone convicted three times of offenses designated by statute as “most serious”; these included murder, manslaughter, kidnapping, rape, sexual assault, first- and second-degree assault, first-degree burglary, and narcotics trafficking. The federal government followed suit the following year: the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994—the same law that provided federal funding for 100,000 new police officers, and for drug courts that excluded violent offenders—mandated life imprisonment for anyone who (a) was convicted in federal court of a “serious violent” felony, and (b) had previously been convicted in federal or state court of either two “serious violent” felonies, or one “serious violent” felony and one “serious drug offense.” The law defined “serious violent felony” to include, in general, murder, manslaughter, rape or sexual assault, armed or aggravated robbery—and any other offense, punishable by ten years or more in prison, that involved either the actual, attempted, or threatened “use of physical force against the person of another” or “a substantial risk of physical force against the person of another.” The 1994 federal crime bill also required any state that wanted federal funding for prison construction to demonstrate that it had increased both the percentage of violent offenders sentenced to prison and the average prison time served by violent offenders.50

The year 1994 also saw the adoption of California’s Three Strikes law, which reached further and was considerably more punitive than the federal and Washington State versions. Like its Washington State counterpart, the California law was adopted by voter initiative. The California measure passed in the wake of the highly publicized abduction, sexual assault, and murder of a 12-year-old girl, Polly Klaas, by a repeat violent offender on parole. The California Three Strikes law prescribed long, mandatory sentences for convicted felons with two previous convictions for “violent” or otherwise “serious” felonies. There were also somewhat shorter, but still quite harsh, mandatory sentences for “second strikers”: convicted felons with a single previous conviction for a “violent” or “serious” felony. By the end of 1995, twenty-four states had enacted Three Strikes laws. Today, almost every state has laws mandating long, additional sentences, often called “sentencing enhancements,” for repeat violent offenders. These laws—particularly California’s, which remained the most draconian—helped to ensure that incarceration rates continued to climb in the United States throughout the 1990s, even as crime rates, including rates of violent crime, plummeted. Roughly a quarter of all California prisoners today were sentenced under the Three Strikes law, and that has been true for over ten years.51

Even more than the harsh penalties the Three Strikes laws imposed on violent offenders, the politics and debates surrounding these laws demonstrated the extraordinary role that violence had come to play in criminal law by the early 2000s. Polly Klaas was one of a series of victims of violent crime—most of them young, female, and white—who were invoked repeatedly by advocates of tougher sentences for repeat offenders. Victims of violent crime became, as Jonathan Simon has written, “the idealized subject of the law.” Even skeptics of Three Strikes laws often reinforced the idea that the criminal justice system should focus its energies and its harshest penalties on violent offenders. Three Strikes laws were criticized for counting, as “strikes,” crimes like burglary that were not truly violent. Opponents warned that the laws might even force the release of “violent pretrial felons,” by crowding jails and prisons with nonviolent offenders.52

The “violent felon” had become the polar opposite of the “low-level drug offender.” The latter deserved mercy and understanding; the former needed and deserved carceral containment. That dichotomous view of criminal justice has proven remarkably durable. In 2019, in his first term on the Supreme Court, Justice Kavanaugh dissented at length from the Supreme Court’s invalidation of a federal statute mandating extra prison time for offenders who use or carry a firearm while committing a “crime of violence.” The Court said the statutory definition of “crime of violence” was unconstitutionally vague. Justice Kavanaugh disagreed, and he added this warning about the implications of the Court’s decision: “The inmates who will be released are not nonviolent offenders. They are not drug offenders. They are offenders who committed violent crimes with firearms, often brutally violent crimes.”53

What Is a “Violent” Crime?

The more that violence matters in criminal law, the more it matters how violence is defined: which crimes are categorized as violent and which are left out of that category. That turns out to be complicated. Most states, and the federal government, have statutes specifying which offenses count as “violent” for purposes of recidivist sentence enhancements, and the list varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Louisiana considers purse snatching to be violent; most other states do not. Arkansas and Rhode Island treat larceny as a violent offense. Mississippi categorizes statutory rape as violent. Delaware and Oklahoma treat dealing in child pornography as a violent offense; New Hampshire classifies possession of child pornography as violent. In many states the “violent” offenses that trigger sentence enhancements are the same ones that restrict eligibility for parole, but other states have two separate lists. Sometimes the “violent” crimes addressed by repeat offender statutes are the same ones that make a defendant ineligible for drug court or veterans court, but frequently they are not. In Louisiana and Oklahoma, for example, the same list of violent offenses governs sentence enhancements, restrictions on parole, and disqualification for therapeutic courts. Mississippi uses a single list of “crimes of violence” to determine sentence enhancements, restrictions on parole, and eligibility for drug court, but a narrower list for purposes of restricting access to veterans court. Connecticut uses a different list of violent crimes for sentence enhancements than for parole eligibility. California, as we have seen, uses the same list.54

Still, it is possible to generalize. Every statute mandating longer sentences for violent recidivists classifies murder and rape as violent, but almost every one of these statutes also includes some crimes that are not obviously violent—like purse snatching, larceny, statutory rape, or child pornography—and each of these statutes also excludes a wide range of criminal conduct that would satisfy almost any nonlegal definition of “violent.” Most states treat arson as a violent offense, even if no one is endangered. It is also common for states to include child molestation and related offenses in the list of crimes that serve as predicates for recidivist sentence enhancements; sometimes this is done simply by labeling these crimes as “violent,” and sometimes the statutory category itself is relabeled to include sexual as well as violent offenders.

A wide range of sexual offenses tend more and more to be treated as “violent,” either by definition or in effect. As we have seen, many Three Strikes laws treat sexual offenses, even when nonviolent, as predicates for recidivist sentence enhancements; the predicates include, for example, distribution or possession of child pornography. Similarly, the federal “First Step” Act—a relatively modest effort at decreasing rates of imprisonment, enacted with bipartisan support in 2018—expanded eligibility for compassionate release, but excluded prisoners convicted of either violent crimes or sexual offenses, including offenses involving child pornography. And an initiative approved by Florida voters that same year re-enfranchised offenders who had completed their sentences, except for those convicted of murder or any “felony sexual offense”; the latter category, again, includes possession of child pornography. One could say that the Florida law treats consumers of child pornography as being more “violent” than armed robbers, but the initiative—which does not use the term “violent”—might be more accurately described as stepping away from the prevailing modern focus on violent offenders as the most blameworthy and the hardest to forgive. It is a return in a way to the emphasis on sexual offenses, rather than violent offenses, in defining crimes of “moral turpitude.” And it is in keeping with the trend over the past two decades to direct greater police and prosecutorial attention to all sexual offenders and to subject them to significantly harsher sentences. (During the coronavirus pandemic of 2020, when many prisoners were granted early release in order to reduce the spread of the virus, prisoners convicted of sex offenses, like those convicted of violent crimes, were often deemed ineligible.) It is consistent, too, with the increasingly frequent identification of “sexually violent predators” as the worst of violent offenders, a category apart within a category apart.55

Violence remains the central preoccupation of American criminal law, however, and so the definition of violence remains critical. A key part of that definition, in practice, has to do with burglary. Most states treat at least some forms of burglary as violent; so does the federal government, as we will see. Sometimes burglary has to be aggravated to count as violent. That can mean that only nighttime burglaries are classified as violent, or only residential burglaries, or only burglaries when someone is home. In some states, a burglary counts as violent only if the burglar carries a deadly weapon. What is almost never required, though, is that the burglar actually attack or physically threaten someone.56

Burglary is the largest and most important statutory addition to the category of violence. The largest and most important statutory subtraction from that category is simple assault. Most sentencing statutes targeting violent recidivists include aggravated assault as a violent offense, but none include ordinary assault. In most, if not all, jurisdictions, simple assault is not just excluded from the category of violent felonies; it isn’t a felony at all. That makes the difference between aggravated and simple assault of very great consequence. In Wyoming, for example, simple assault is punishable only by a fine of up to $750, or, if the victim is harmed, by up to six months in jail. (Following older, common-law usage, Wyoming calls an assault that succeeds in injuring the victim a battery.) Aggravated assault, on the other hand, carries a maximum sentence of ten years, even for a first offense, and it serves as a trigger for Wyoming’s recidivist enhancements. Wyoming is utterly typical in this regard: virtually every jurisdiction treats simple assault as a misdemeanor, and often as a low-grade misdemeanor at that, and virtually every jurisdiction treats aggravated assault as a serious felony, punishable by a long term of imprisonment and providing the basis for recidivist sentence enhancements.57

The line between simple assault and aggravated assault is hazy, though. In Wyoming, as in most states, an assault can be aggravated by the use of a dangerous or deadly weapon, or by causing “serious bodily injury,” intentionally or with great recklessness. (An assault and battery is also aggravated in Wyoming if the offender knows the victim is pregnant; Florida has a similar provision.) The FBI uses a similar rule for deciding whether an assault reported to the police should be viewed as “aggravated” and therefore included in the violent crime statistics produced by its Uniform Crime Reports program. The FBI calls an assault aggravated if it involves a weapon or causes “obvious severe or aggravated bodily injury.”58

The trick is defining a “weapon,” or a “dangerous” or “deadly” weapon, and deciding what injuries count as “serious.” In some states, hands and other body parts can be “deadly weapons”; in other states they cannot. Sometimes dogs are classified as “deadly weapons”; sometimes they are categorically excluded. Ditto for canes, walking sticks, and other everyday objects used as bludgeons. The rapper and music producer Sean “P. Diddy” Combs was arrested in 2015 for aggravated assault after angrily waving a kettlebell during an argument in a college gym, although the charges were dropped. Some courts say that bare feet cannot be classified as “deadly” or “dangerous weapons,” but that kicking or stomping can qualify as aggravated assault if the assailant is wearing shoes or sneakers.59

There is even more ambiguity about what constitutes a “serious bodily injury.” For purposes of the Uniform Crime Reports, the FBI says that injury cannot count as “severe or aggravated” unless it involves “broken bones, loss of teeth, possible internal injury, severe laceration, or loss of consciousness.” But the courts of some states define “serious bodily injury” to mean any injury that is “graver and more serious … than an ordinary battery.” In other states, “serious bodily injury” is defined by judicial decisions, or in some cases legislation, to mean injury that gives rise, or could reasonably give rise, to “substantial risk of death” or “apprehension of danger to life, health, or limb.” A Wyoming statute sets forth a particularly elaborate test for “serious bodily injury,” requiring a “bodily injury which: (A) Creates a substantial risk of death; (B) Causes severe protracted physical pain; (C) Causes severe disfigurement or protracted loss or impairment of a bodily function; (D) Causes unconsciousness or a concussion resulting in protracted loss or impairment of the function of a bodily member, organ or mental faculty; (E) Causes burns of the second or third degree over a significant portion of the body; or (F) Causes a significant fracture or break of a bone.”60

The Wyoming Supreme Court has applied this definition strictly. For example, the court overturned a conviction for aggravated assault in a case where the defendant beat the victim with his fists and struck him on the head with an iron stove grate, “causing profuse bleeding and permanent scarring,” and an accomplice hit the victim with a baseball bat. The victim was treated at an emergency room but did not require “stitches, inpatient hospitalization, surgery or follow-up medical treatment.” The Wyoming Supreme Court held that these facts supported a conviction only for simple assault, not for aggravated assault.61 This decision is not an outlier. A New Jersey court, for example, found that a broken nose was not “serious bodily injury,” because there was no evidence that “the victim suffered a ‘loss or impairment’ of a bodily function,” let alone that the condition was “protracted, prolonged, or extended in time.”62 Another Wyoming decision reversed an aggravated assault conviction in a case where the defendant punched and kicked his girlfriend for an hour and a half and tried to stuff his hands down her throat. The victim lost consciousness, could not eat for five days, suffered facial fractures, and required twenty stitches, but the Wyoming Supreme Court concluded that “the legislature intended that the crime of aggravated assault be based upon injuries significantly more serious.”63

There are decisions from other jurisdictions taking a more expansive view of what constitutes a serious bodily injury. The courts in several states, for example, have held that losing all or part of a tooth can constitute “serious bodily injury” and therefore turn a simple assault into an aggravated assault.64 It is clear, though, that many physical attacks, even “brutal” attacks, fall outside the realm of “violent” criminal conduct that can trigger recidivist enhancements.65 At the same time, in virtually every jurisdiction, defendants can be convicted of “violent” felonies that trigger recidivist enhancements without ever attacking anyone or even threatening anyone. In Wyoming, for example, a burglar who carries a simulated pistol is guilty of aggravated burglary, which is a “violent felony” for purposes of the state’s “habitual criminal” law. In several states, any residential burglary counts as a “violent felony,” even if the burglar is unarmed and no one is at home; in all of these states, though, an unarmed, nonsexual assault generally is not even a felony, let alone a violent felony, unless it results in, is aimed at causing, or is likely to cause serious bodily injury.66

In practice, concludes the legal scholar Franklin Zimring, “aggravated assaults range in seriousness from menacing gestures to attempted murder,” and how the assaults are charged and classified is typically a matter of official discretion. Arrest rates for simple and aggravated assault soared in the late 1980s and 1990s, for example, but this does not appear to have reflected any actual increase in violent attacks. It appears instead to have been the result of changes in the standards that police departments applied in deciding when to treat an attack as an assault, and where to draw the line between simple and aggravated assaults. When Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana, ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2019, critics noted that the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports showed a rise in violent crime in South Bend during his time in office. But that appears to have been a statistical artifact, resulting from a change in the way the South Bend Police Department determined whether to classify an assault as “aggravated,” and therefore count it as a violent offense.67

The category of violent crime is thus very much a social and legal construct, varying from state to state, from statute to statute, and from case to case. It reflects a series of many small judgments about which kinds of conduct are serious enough to deserve the legal consequences prescribed for violent crimes—particularly the stiff mandatory sentences, exclusion from therapeutic courts, and restrictions on parole. It never includes all criminal conduct that would satisfy ordinary, everyday understandings of the word “violent,” and it frequently includes a good deal of conduct falling outside those understandings. That does not mean the category should be abandoned or that its use is a mere pretext; it is in the nature of legal categories to give rise to ambiguities that invite ad hoc redefinitions. But the artificiality and variability of the legal category of violent crime should remind us that there is nothing natural or inevitable about the category: it does not describe a clear, readymade distinction between offenders who deserve sympathy and those who do not.

Burglary, Career Criminals, and Violence

The rising salience of violent crime, the difficulty defining violent crime, the peculiar role played by burglary in the construction of the category of violent crime, and the hydraulic pressure exerted on penalties for violent crime by the pushback against the war on drugs—all of this can be seen in a nutshell in the story of the Armed Career Criminal Act (ACCA) of 1984, probably the most consequential of the many federal criminal statutes now targeting violent crime. The story of the ACCA is long and convoluted. It begins in 1981, with anticrime legislation focused not on violent crime but on robberies and burglaries committed by “career criminals.”

The principal sponsor of the 1981 legislation, and of the 1984 bill that grew out of it, was Senator Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, a Yale Law School graduate who had previously served for thirty years as the Philadelphia district attorney. In 1981 Specter began a multiyear effort to mandate long federal sentences for recidivist robbers and burglars. Specter’s first proposal was to mandate a life sentence for anyone convicted in federal court of robbery or burglary while armed with a gun, if the defendant had twice previously been convicted of robbery or burglary. That proposal ultimately became part of an omnibus crime bill sent to President Reagan in December 1982, but along the way the sentence was changed to a minimum of fifteen years and a maximum of life, and use of the statute was conditioned on the approval of state prosecutors. Reagan pocket vetoed the 1982 crime bill, in part because he objected to this grant of authority to local officials over federal prosecutions. Following the veto, Specter immediately reintroduced his career offender proposal, but moved the discretion whether to file charges back to federal prosecutors, and Representative Ron Wyden of Oregon introduced similar legislation in the House of Representatives. Concerns were again raised about federalism, this time by the American Bar Association and the National District Attorneys Association, and as a result the House bill was amended so that rather than creating a new federal offense, it simply mandated a longer, fifteen-year sentence for defendants with three prior convictions for burglary or robbery who were subsequently convicted of the venerable federal law prohibiting convicted felons from possessing firearms. In this form the ACCA passed both the House and Senate and was signed into law as part of the Comprehensive Crime Control Act (CCCA) of 1984.68