Fred Schwed opened his 1940 classic book, Where Are the Customers’ Yachts? with the following introduction:

“Wall Street,” reads the sinister old gag, “is a street with a river at one end and a graveyard at the other.” This is striking, but incomplete. It omits the kindergarten in the middle, and that’s what this book is about.

Fred chronicled the madness of the 1920s and 1930s boom-bust cycle hanging out as a customer in the brokerage houses of Wall Street. He managed to stick around long enough for the 1950s’ bull run before passing away in 1960. Had he the ability to come back now, I believe he’d be highly amused at the fact that this Wall Street “kindergarten” has since become the dominant power in virtually every facet of our daily lives.

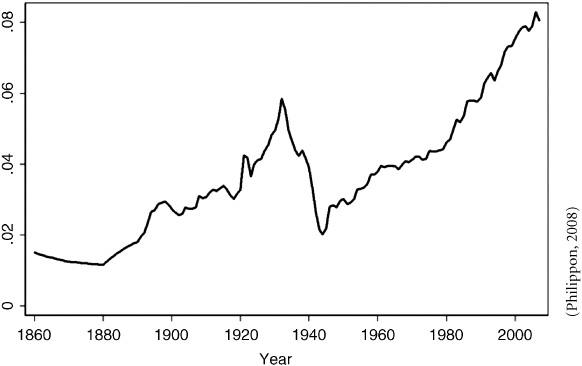

According to the research of NYU Stern professor Thomas Philippon, the financial sector’s share of U.S. GDP has more than tripled from when Schwed was writing in 1940 (see Figure 1.1). The economic resources we spend on commercial banking, investment banking, private equity, and insurance have grown from 2.5 percent of the total pie to a whopping 8.3 percent through 2006. Philippon notes that each surge in finance’s share of annual GDP over the years has been commensurate with an important societal advance, like the heavy industrial growth of the late 1800s, the electricity and automobile revolutions of the 1920s, and the IT spending explosion that began in 1980. But by the turn of the millennium, the financial services sector began to grow purely for the sake of growing. There was little benefit to the rest of the nation as financial engineers found more and more ways to keep finance itself in a self-perpetuating boom phase. And we know what happened next: the repo men came and took your no-money-down, canary yellow Hummer right out of the driveway of that house you didn’t really belong in.

Figure 1.1. GDP Share of Financial Industry

One of the most obvious signs of this metastasizing in the financial sector could be seen in the employment tallies at the banks and real estate firms themselves. We’re talking about over 7 million people whose jobs consist mainly of pushing your money back and forth, up and down, in and out. The industry’s sheer size may have gotten a bit silly, but its compensation policies are now bordering on slapstick. In 2008, Philippon told the Wall Street Journal that “in 1980, finance workers made about 10 percent more than comparable workers in other fields … by 2005, that premium was 50 percent.” No wonder people don’t want to do anything else with their lives other than flip houses, trade stocks, and sue each other.

Fueling much of this boom in revenue, profits, employment, and compensation growth for the finance industry was the global brokerage sales force. These are the men and women who go to work each day to find a buyer for every product and service that Wall Street can dream up. Heaven forbid they should take a month off; one can just picture the skyscrapers toppling and airplanes dropping out of the sky.

Brokerage firms are often referred to as “shops” by those who work in them, and this is because, like any other type of shop, the goal is to sell stuff to people. A brokerage firm, or broker-dealer, is in the business of facilitating the buying and selling of financial products, instruments, and, nowadays, advice.

This is not necessarily a bad thing.

Human beings in general are innumerate, and the vast majority of Americans don’t have the time or interest to learn the basics of investing, let alone the intricacies.

There was a popular recent study that polled teenagers from around the world as they exited a mathematics exam. In terms of their scores, it should come as no surprise that the American students finished somewhere in the middle of the pack compared with their global counterparts. But when asked about how they thought they had done, it was those same average-scoring American kids who led the survey in self-confidence about their own performance. This is both wonderful and terrifying at the same time. There is an indomitable beauty in this uniquely American attitude, but unfortunately, overconfidence and middling numerical savvy do not exactly align well with successful investing. This is why there will always be a need for investment advice and a role for those who give it professionally.

The truth about civilian investors is that, in the aggregate, they will almost always enter and exit stocks and bonds at the wrong time. This has been proved over and over again, whether we’re looking at mutual fund inflows and outflows, 401(k) contributions, retail brokerage firm margin debt, or almost any other gauge that tells us what the average investor is up to. Nothing makes this point more starkly, however, than a look at extreme readings in sentiment polls like the one produced by the American Association of Individual Investors (AAII).

The AAII conducts a weekly sentiment poll to track the mood of retail market players. The historical averages for this highly regarded poll are roughly 39 percent bullish, 30 percent neutral, and 30 percent bearish. As the S&P 500 was putting in its high-700s bottom in late 2002 and early 2003, this survey was repeatedly flashing extreme bearish sentiment readings of over 50 percent (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. S&P 500: 2002–2007

An even more telling example of this phenomenon took place during the bottoming process that followed the credit crisis. During the week of March 5, 2009, the S&P was sitting at about half the level of its 2007 bull market peak; it had been gruesomely poleaxed in half over the course of the prior 15 months. The AAII sentiment survey that week reported 18 percent bulls and 70 percent bears—a record-breaking measure of bearish sentiment that has never been seen before or since. Spoiler Alert: The S&P 500 would put in an actual bottom at 666 four days later. It would be up 20 percent within a matter of months—quite an inconvenient rally given that most people had been cleared out of their stocks by this time. Within 24 months the market would achieve a double off its March 2009 low, this double happening while a huge swathe of investors watched from the sidelines in disbelief.

While there are those who have found success investing on their own, the great majority of what we’ll call “ordinary” people would be better off getting some help. This is certainly not to say that they should take and pay for the advice of just anyone who is willing to give it!

In the aggregate, the professionals are not much better at picking market bottoms; sentiment on Wall Street matched the panicky mood on Main Street during this period for the most part. But there was a difference between how the pros and most individuals reacted to this widespread pessimism that is very important to understand. When it became more likely that we had seen the worst of what Mr. Market had in store for us, the pros were more willing to pull the trigger and begin buying stocks again, while many civilians simply couldn’t snap out of their trance until much later. To some extent, you could argue that the brokerages had an extra incentive to boldly pull the trigger—you can’t charge commissions to an account that is sitting in cash. This is a fair point, one that we’ll be discussing at length a bit down the road.

In the spring of 2009, I was managing a branch office and 30 stockbrokers, and they in turn were working with thousands of retail accounts. The brokers were every bit as gun-shy about committing capital as their customers were in the post-Lehman wastelands of the stock markets. But they did it anyway because it was the only thing you could do when the market has erased 15 years’ worth of forward progress for the major indexes. The best guys I know from firms all over The Street kept buying, even when their initial forays resulted in immediate drawdowns, even with the clients holding their hands over their eyes, not daring even a peek.

I do not wish to make the point here that professional investors have proved themselves to be naturally adept timers of the market. What I am attempting to convey, however, is that professionals tend to be less emotional. Part of that stems from the fact that professionals are managing other people’s money, and so they have that luxury of emotional detachment. Another part stems from their being desensitized to a lot of the volatility by the sheer fact that they live with it 32½ hours a week while the markets are open. Psychologists do not psychoanalyze themselves when they find themselves overwhelmed; they have their own shrinks on speed dial. An outside, detached perspective is needed sometimes, especially when it comes to money—one of the most emotionally intense aspects of our lives.

The truth is, it is only at market peaks that most ordinary Americans get really interested and engaged in the stock market. They build up a knowledge base and a passion for investing just in time for the next crushing bear market to begin. In fact, the last bull market ended in 2000, just as stock market investing had supplanted baseball as the national pastime. Then the new national pastime became real estate, and a discussion about stocks got you laughed out of the room. This lasted until 2007 when stocks staged a credit-related echo-bull market, topping out before ultimately following the housing bull market right off a cliff.

Fortunately, America’s new pastime is neither baseball nor stocks nor housing. Rather, it is checking our phones for e-mails; brushing our Cheetos-stained fingertips across them as though we’re conducting the world’s tiniest symphony. By which I mean we might be somewhat safe for a while.

By highlighting these recent financial manias and denigrating the participation of retail investors at their peaks, I am by no means inferring that if those investors had just listened to the brokerage industry, they’d have been fine. In fact, quite the opposite. Brokerage firms exist to cater to the whims of investors. When those whims tend toward speculation in a given investment theme, the brokerages roll out the drawing boards and begin cooking up products and strategies to satiate those appetites and meet the demand head-on.

This is all to be expected; once again we are talking about shops—retail stores that happen to sell intangibles. You wouldn’t fault a Korean grocer for displaying a variety of different apples the day after Oprah tells her audience that they are to eat three apples a day, would you?

The bottom line is that the brokers need something to sell. This product creation mechanism takes a “story” that investors will be receptive to and turns it into profits for the brokerage firm.

We are also not talking about a phenomenon that is in any way unique to Wall Street. Hollywood understands this concept very well, and the vast majority of films that make it to the production stage do so as a result of what the studios believe will sell to audiences. Sequels are rarely about an artistic desire to continue the story. They are about a financial desire to continue the story. There is nothing inherently wrong with this, as it makes moviegoers happy to revisit characters and worlds they love. But these films are not art for the most part, and they are in many ways unnatural, forced creations of commerce.

Every once in a while something is produced in Hollywood for its artistic merits alone, but even in these cases a hard charger like Harvey Weinstein will come in as a distributor to push the film. No one should be surprised by this; the art versus commerce debate has been raging since the first Greek playwrights complained about the gyro vendors traipsing up and down the amphitheater’s aisles during a production of Antigone.

Hollywood’s business-savvy players will make sure that even if they end up with an art film that bombs at the box office, there will still be profits to wring from it. This is the reason there are so many movies up for awards each year that no one you know has actually seen. The studio says, “Well, we may as well go for some prestige and push this for a Golden Globe; at least we can juice the DVD sales and cable rights that way.”

In much the same manner, the brokerage firm does not require a “big hit” in order to make money. The selling concessions or fees in the vast majority of products accrue to the seller of the product regardless. The success or failure of a particular instrument can only be judged over the long term. Should it be judged to have been subpar, no matter, because the commission’s already been paid long ago. This calculation is at the very heart of the business model. The brokerage business has always been a very “heads we win, tails somebody else loses” proposition. The client has the financial risk; the broker has the “reputational” risk. The nature of selling financial products and intangibles (like the prospect for earning profits in a given investment) is such that a victory justifies all manner of fees and a loss is the market’s fault.

How does this continue year-in, year-out? Well, it’s not exactly like they’ve stopped making new people in this country (it’s way too fun a manufacturing process), and so the brokerage firm rarely runs out of new investors to sell things to.