Visions and Confrontation (7:1–9:10)

Swarms of locusts after the king’s share … just as the second crop was coming up (7:1). This first vision shows God preparing a locust swarm to devastate the country (for locusts, see comments on 4:9). The detail of the crops and the timing of the plague are particularly important.

There were two main crops each year in ancient Israel. The first was sown in the autumn, watered by the late autumn rains and harvested in the spring. The second was sown in winter, watered by the spring rains and harvested in the early summer. The Gezer calendar (see sidebar, “The Gezer Calendar”) gives a good summary of the agricultural year. This probably remained the pattern in later centuries, though there is no other extrabiblical textual evidence.

The “king’s share” (lit., “mowing”) is mentioned only here. This was obviously some or all of the first harvest. Whatever the proportion, it shows that the king took a significant part of the best produce in a heavy tax. Samuel’s warning of the burdens of kingship was sadly fulfilled (1 Sam. 8:11–17).

The timing of the plague means that the monarchy already has its share, so the king may remain unconcerned about the plight of the ordinary people, but their share is completely wiped out as locusts “strip the land clean.” Lack of rain during the long, dry summer will make further crops impossible, resulting in famine and starvation.

Forgive … this will not happen (7:2–3). The Hebrew verb “forgive” (slḥ) is used in the Old Testament only of divine forgiveness, such as following the wilderness rebellion (Num. 14:20), in Solomon’s temple prayer (1 Kings 8:30), and in a memorable Isaianic text (Isa. 55:7). Here Amos fulfills the important Old Testament prophetic role of interceding on behalf of the people, a role not evidenced in other cultures. His appeal is not based on Israel’s repentance but implicitly on God’s relationship with Israel, which would cease if the nation was wiped out. Perhaps surprisingly in light of previous oracles, God relents.

Judgment by fire (7:4–6). This second vision develops a common motif (see comments on 5:6). This fire even consumes “the great deep” (tehôm), the cosmic deep beneath the earth that is the source of its seas and river and is sometimes associated with the underworld.81 If the earth’s extremities are consumed, what hope is there for humans? Again the prophet intercedes, and again Yahweh relents.

A plumb line (7:7–8). The meaning of the vision is clear: Yahweh uses a hand-held instrument that has some association with a wall in order to illustrate coming judgment. However, the Hebrew text is less clear. The Hebrew term ʾ anāk (“plumb line”) has the same stem as the Akkadian term ʾannaku. The latter was thought to mean “tin or lead,” hence the interpretation as “lead weight” (i.e., plumb line). However, recent study suggests that ʾannaku means specifically “tin,” not lead, and tin is too light to make an effective plumb line. Various other proposals have been made regarding the meaning of ʾ anāk and the nature of the vision,82 but none is convincing. Nevertheless, whatever Amos sees in Yahweh’s hand, he understands it as an illustration of judgment.

The king’s sanctuary and the temple of the kingdom (7:13). These descriptions of Bethel occur only here in the Old Testament. However, it was common for ancient Near Eastern monarchs to exercise patronage over sanctuaries;83 in the Jerusalem temple there was even a special entrance for the king.84

Neither a prophet nor a prophet’s son (7:14–15). Amos immediately responds to Amaziah’s charge that he is a professional who “earns his bread” by prophesying. The charge implies that Amaziah had no concept of any other form of prophetic ministry. Amos immediately declares that he is a farmer (see comment on 1:1) called by God for a specific prophetic mission. Amos had a clear sense of divine call, something well attested in other biblical prophets but not in prophetic texts from surrounding cultures (see sidebar on “Prophets” at 2:11).85

You say … the Lord says (7:12–17). In response to Amaziah’s prohibition, Amos delivers a specific and chilling personal prophecy of destitution and death. This is similar to curses elsewhere, such as a treaty of the Assyrian Asshur-nirari V, which contains the lines:86

May Matiʾilu become like a prostitute and his soldiers women.

May they receive gifts like a prostitute in the square of the city.

A basket of ripe fruit (8:1–2). The Hebrew writers loved wordplays. Here “summer fruit” (qāyiṣ, usually figs) is punned with “end” (qēṣ).87 Wordplays do not translate easily from one language to another, but the NIV does well to match “ripe fruit” with “the time is ripe.” Ripe fruit normally means harvest celebration. Here it presages ripeness for judgment.

Wailing … bodies … silence (8:3). The horror of the scene is matched by the disjointedness of the text. Hebrew writers sometimes capture the horror of the moment in their very style.88

Rise like the Nile … then sink like the river of Egypt (8:8). Egyptian agriculture relied heavily on the annual flooding of the Nile. The waters flooded in September and receded in October, leaving a short winter period for cultivation of crops. Occasionally the flood was too weak, with catastrophic results, and Egyptian texts often note “a year of low Nile” with hunger and misery.89 The powerful image of a rising and flooding river occurs in a variety of prophetic contexts.90 Here it may well be another prediction of the coming earthquake (Amos 1:1), which would convulse the solid earth as if it was water. The imagery is repeated in 9:4.

Sun go down at noon (8:9–10). All the joyful revelry noted in previous chapters will be replaced by darkness, gloom, and mourning. The darkened sun, a common theme in judgment oracles, may well indicate an eclipse.

In the ancient world eclipses were interpreted as divine anger and portents of disaster. For the Assyrians a full solar or lunar eclipse portended the death of the king himself. So when one occurred, the king often invoked an ancient substitute ritual, in which a commoner was temporarily enthroned while the real king was disguised. After a short time the substitute king was killed, fulfilling the omen, and the real king resumed the throne. During Esarhaddon’s short reign (680–669 B.C.), there were many eclipses, and this ritual was invoked at least four times.91

Samaria … Dan … Beersheba (8:14). The focus of worship is clear only for Dan, where it is “your god.” For Samaria, it is “the shame” (ʾašmat), an unusual but understandable epithet for the “calf of Samaria” (Hos. 8:6). Adding different vowels would give the name “Ashima” (ʾašimat), but worship of this goddess was only introduced later by deportees from Hamath (2 Kings 17:30). For Beersheba, the puzzling focus of worship is literally “the way [derek] of Beersheba.” Perhaps derek here does not have its common meaning “way” but is a rare homonym meaning “power.”92

Ruins of the sanctuary at Dan

Kim Walton

Altar … people (9:1). Unlike the first four visions, Amos here is merely a spectator as Yahweh proclaims horrendous judgment to be enacted, presumably by the Assyrians, on the Bethel temple. The tops (or capitals) of the pillars supporting the roof will be smashed so violently that the building will be destroyed down to its foundations. Leaders and commoners alike will be slaughtered. The Assyrians, like most ancient conquerors, executed leaders of conquered peoples and any they deemed to be rebels. Sargon, who eventually captured Samaria, boasted regarding a rebel Hittite: “Himself I flayed; the rebels I killed in their cities and established (again) peace and harmony.”93

None will escape (9:1–4). Five flight scenarios are envisaged in these verses, with two opposing pairs from the cosmic world (underworld, heavens) and the natural world (mountain, seas), and a single scenario in the human world. None of these provides escape from divine retribution. A fourteenth-century El Amarna letter similarly affirms that neither heaven nor the underworld can provide escape from the Egyptian Pharaoh.94

The depths of the grave (9:2). This is literally “Sheol” (Heb. še ʾôl). A reference to the cosmic extremity of the underworld is clear here from its parallelism with “heavens.” The NIV usually translates še ʾôl as “grave,”95 but this significantly underplays its underworld allusion,96 and several texts like the present show that this translation is inadequate.97

A repeated biblical theme is that the dead in Sheol are cut off from Yahweh and can no longer praise or petition him (see Ps. 6:5; 88:5, 10–12; 115:17; Isa. 38:18). However, another repeated theme reflected here is that God’s authority extends even to Sheol, and nothing there is hidden from him (e.g., 1 Sam. 2:6; Prov. 15:11). While the canonical writings have little sustained reflection on the underworld, they show no difficulty in maintaining these themes as complementary.

The serpent (9:3). Many ancient cultures envisaged a great sea monster or serpent (the Heb. nāḥāš also means “snake” on dry land, as in the Garden of Eden). In the Old Testament several poetic texts note that at creation God defeated this variously named and sometimes multiheaded monster. Note, for example:

Ps. 74:3: You broke the heads of the monster in the waters … crushed the heads of Leviathan.

Ps. 89:10: You crushed Rahab like one of the slain.

Isa. 51:9: Was it not you who cut Rahab to pieces, who pierced that monster through?98

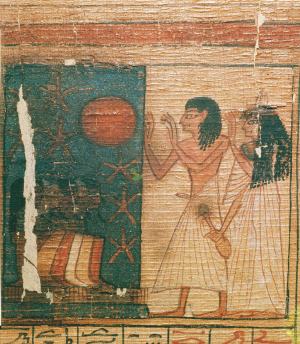

God slays a seven-headed monster.

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

Other texts envisage the monster as still existing; see, for example, Job 7:12: “Am I the sea, or the monster of the deep, that you put me under guard?” Here God will command this very creature to fulfill his purpose.

In the ancient world the great monster of the deep often signified chaos, which the gods and their human servants kept at bay. For instance, in the well-known Babylonian Enuma Elish, Marduk defeats the old goddess Tiamat, who represents primeval chaos. Also, many Mesopotamian and Egyptian pictures survive of a serpent rearing up and being speared down its throat, and some of a seven-headed monster.99 While the great sea serpent was a widespread concept,100 in Israel’s texts, it only occurs occasionally and in evocative poetic texts, where it is clearly a foil for presenting God’s power.

I will fix my eyes upon them for evil (9:4). An Akkadian text mentions “eyes which look at you to cause evil.”101 There was a widespread ancient view that a human could fix another with an “evil eye” and hence cause them harm.102 This is reflected in later Judaism, with an incantation preserved in the Babylonian Talmud:

Take the thumb of the right hand in the left hand and the thumb of the left hand in the right hand, and say: “I, so-and-so, am of the seed of Joseph over whom the evil eye has no power.”103

Lofty palace (9:6). This uncertain word (cf. NIV note) probably means “upper chambers,” suggesting a palatial structure. Yahweh’s majestic heavenly palace is noted elsewhere (Ps. 104:3), but it is only an occasional Old Testament theme, in contrast to a Ugaritic text that discusses at length the construction of a palace for Baal and whether or not to add a certain window.104

Cushites … Philistines … Arameans (9:7). The Cushites inhabited the distant upper Nile (now Sudan). In Amos’s time they seemed a strange and exotic people, as described in Isaiah 18:1–2:

… the land of whirring wings

along the rivers of Cush….

a people tall and smooth-skinned,

… a people feared far and wide,

an aggressive nation of strange speech,

whose land is divided by rivers.

Cushites, Philistines, and Arameans

In the mid-eighth century B.C. the Cushites expanded north into a fragmented Egypt, which they then controlled for nearly a century (ca. 747–664). Some fifty years after Amos, a Cushite pharaoh named Tirhakah challenged the Assyrians besieging Jerusalem, giving it temporary respite (2 Kings 19:9). For Arameans and Philistines, see comments on 1:3–8. The tradition that the latter came from Caphtor (i.e., Crete) is repeated in Jeremiah (Jer. 47:4).105

Shaken in a sieve (9:9). Amos employs here yet another agricultural image, that of sieving grain. The sieve retains all the stalks, pebbles, and other rubbish, while the finer grain falls through. So God promises to preserve a loyal remnant of the house of Jacob, while the large majority of unconcerned “sinners” will perish.