High-performance windows and glazing contribute to a LEED Gold rating for the University of Washington's Poplar Hall. (Architect: Mahlum. Photo by Joseph Iano.)

18

WINDOWS AND DOORS

Egress Doors and Accessible Doors

Other Window and Door Requirements

Safety Considerations in Windows and Doors

Structural Performance and Resistance to Wind and Rain

WINDOWS

The word window is thought to have originated in an old English expression that means “wind eye.” The earliest windows in buildings were open holes through which smoke could escape and fresh air could enter. Devices were soon added to the holes to give greater control: hanging skins, mats, or fabric to regulate airflow; shutters for shading and to keep out burglars; translucent membranes of oiled paper or cloth, and eventually of glass, to admit light while preventing the passage of air, water, and snow. When a translucent membrane was eventually mounted in a moving sash, light and air could be controlled independently of each other. With the addition of woven insect screens, windows permitted air movement while keeping out mosquitoes and flies. Further improvements followed over the centuries. A typical window today is an intricate, sophisticated mechanism with many layers of control: curtains, shade or blind, sash, glazings, insulating airspace, low-emissivity and other coatings, insect screen, weatherstripping, and perhaps a storm sash or shutters.

Windows were formerly made on the construction site by highly skilled carpenters, but today nearly all of them are produced in factories. The primary reasons for factory production are higher production efficiency, lower cost, and, most important, better quality. Windows must be made to a very high standard of precision if they are to operate easily and maintain a high degree of weathertightness for many years. In cold climates especially, a loosely fitted window with single glass and a frame that is highly conductive of heat will significantly increase heating fuel consumption for a building, cause noticeable discomfort to the occupants, and condense large quantities of water that will stain and decay materials in and around the window.

Types of Windows

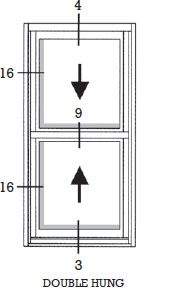

Figure 18.1 illustrates in diagrammatic form the window types used most commonly in residential buildings, and Figure 18.2 shows additional types that are found largely in commercial and institutional buildings. Fixed windows are the least expensive and the least likely to leak air or water, because they have no operable components. Single-hung and double-hung windows have one or two moving sashes, which are the frames in which the glass is mounted (Figure 18.3). The sashes slide up and down in tracks that are part of the window frame. In older windows, the sashes were held in position by cords and counterweights, but today's double-hung windows usually rely on a system of springs to counterbalance the weight of the sashes. A sliding window is essentially a single-hung window on its side, and shares with single-hung and double-hung windows the advantage that tracks in the frame hold the sashes securely along two opposite sides. This inherently stable construction allows single-hung, double-hung, and sliding windows to be designed in an almost unlimited range of sizes and proportions. It also allows the sashes to be more lightly built than those in projected windows, a category that includes principally casement, awning, hopper, inswinging, and pivot windows. All projected windows have sashes that rotate outward or inward from their frames and therefore must be stiff enough to resist wind loads while being supported at only two points.

Figure 18.1 Basic window types.

Figure 18.1 (Continued)

Figure 18.2 Additional window types that are used mainly in larger buildings.

Figure 18.3 Basic window nomenclature follows a tradition that has developed over many centuries. The jamb consists of the head jamb across the top of the window and the side jamb to either side. In practice, the head jamb is usually referred to simply as the head and the side jambs as jambs. The sill frames the bottom of the opening on the exterior side, and the stool does the same on the interior. Interior casings and exterior casings cover the gaps between the jambs and the rough opening, and aprons do the same below the sill and stool.

With the exception of the rare triple-hung window, no window with sashes that slide can be opened to more than half of its total area. By contrast, many projected windows can be opened to almost their full area. Projecting casement windows assist in catching passing breezes and inducing ventilation through the building. They are generally narrow in width, but can be joined to one another and to sashes of fixed glass to fill wider openings. Awning windows can be broad but are not usually very tall. They have the advantages of providing protection from water during a rainstorm, even when open, and of lending themselves to a building-block approach to the design of window walls (Figure 18.4). Hopper windows are more common in commercial buildings than in residential ones. Like awning windows, they will admit little or no rainwater if left open during a rainstorm. Tilt/turn windows (not illustrated) are a type of projected window with clever but concealed hardware that allows each sash to operate both as a side-hinged inswinging window and as a hopper. Window types that are used almost exclusively in commercial and institutional work include horizontally and vertically pivoting windows and top-hinged inswinging windows.

Figure 18.4 Awning and fixed windows in coordinated sizes offer the architect the possibility of creating patterned walls of glass. (Photo courtesy of Marvin Windows & Doors.)

Most tall buildings do not provide operable windows, due to the complexity of balancing varying air pressures on the outside of the building with those of the internal air-handling system. These make it difficult to maintain steady, comfortable air temperatures and speeds within the building. However, with proper design (and in appropriate climates), operable units can be part of a natural ventilation strategy that provides comfortable airflows in place of a mechanical air-conditioning system. On tall buildings, inswinging window types may be preferred, as they are less vulnerable to damage by high windows. For safety reasons, such windows may be fitted with devices that limit the extent to which they can be opened.

A projected window is usually provided with synthetic rubber weatherstripping that compresses snugly around the edges of the sash when the window is closed. Single-hung, double-hung, and sliding windows must rely on brush-type or very low-modulus (highly flexible) weatherstripping that does not exert so much friction as to make operation of the sash difficult. However, these weatherstripping types also may not seal as tightly and are subject to greater wear over the life of the windows. As a result, projected windows are frequently more resistant to air leakage than windows that slide in their frames.

Glazed units installed in roofs are specially constructed and flashed to remain watertight in their sloping or horizontal orientation. Skylights may be either fixed or operable (venting skylight). The term roof window is also sometimes applied to venting skylights; at other times, it is applied more narrowly only to windowlike units that include some kind of inward rotation capability, making glass cleaning easier.

Large glass doors (which are most often supplied by window manufacturers) may slide in tracks or swing open on hinges (Figure 18.1). The hinged French door opens fully and, with its arms flung wide, is a more welcoming type of door than the sliding door, but it cannot be used to regulate airflow through the room unless it is fitted with a doorstop that can hold it securely in an open position. The French door is prone to air leakage along its seven separate edges, which must be carefully fitted and weatherstripped. The terrace door, with only one operating door, minimizes this problem but, like the sliding door, can open to only half its area.

Insect screens may be mounted only inside the sash in casement and awning windows (because the sash swings outward). Screens are usually positioned to the exterior side of other window types. Sliding patio doors and terrace doors have exterior sliding screens, and French doors require a pair of hinged screen doors on the exterior. Pivoting windows cannot be fitted with insect screens.

Glass must be washed at intervals if it is to remain transparent and attractive. Inside surfaces of glass are relatively easy to reach. Outside surfaces are often harder to reach, requiring ladders, scaffolding, or window-washing platforms that hang from the top of the building on cables. Accordingly, most operable windows are designed to allow washing of the outside glass surface from inside the building. Casement and awning windows are usually hinged in such a way that there is sufficient space between the hinged edge of the sash and the frame when the window is open to allow one's arm to reach the outer surface of glass. Double-hung and sliding windows are often designed to allow sash to be rotated or tilted out of their tracks to allow easy access to exterior glass (Figure 18.15). Inward-swinging window types naturally expose their outer glass surfaces to the interior when opened.

As seen in many of the following figures, windows and glass doors may also be combined side by side or stacked vertically to create larger glazed areas with any of a great variety of fixed and operable component configurations.

Window Frames

Wood

Wood is the traditional frame material for windows. It is a fairly good thermal insulator, changes size relatively little with changes in temperature, and, if free of knots, is easily worked and consistently strong. In service, though, wood shrinks and swells with changing moisture content and requires repainting every few years. When wetted by weather, leakage, or condensate, wood windows are subject to decay, though their resistance to decay can be improved with preservative treatments. Knot-free wood is becoming increasingly rare and expensive, so composite wood products are increasingly used. These include lumber made of short lengths of defect-free wood finger-jointed and glued together, oriented strand lumber, and laminated veneer lumber. These materials, although functionally satisfactory, are not attractive, so they are covered with wood veneer on the interior and clad with plastic or aluminum on the exterior (Figures 18.5, 18.6, and 18.7). Clad wood windows account for the largest share of the market for wood-framed windows.

Figure 18.5 Cutaway sample of an aluminum-clad wood-framed window. (Photo courtesy of Marvin Windows & Doors.)

Figure 18.6 A pair of double-hung wood-framed windows in a dwelling. (Photo courtesy of Marvin Windows & Doors.)

Figure 18.7 Large double-hung wood windows and a triangular fixed window bring sunlight and views. (Photo courtesy of Marvin Windows & Doors.)

Aluminum

Aluminum, when used in window construction, is strong, easy to form and join, and, in comparison to wood, much less vulnerable to moisture damage. The extrusion process by which aluminum sections are formed results in shapes with crisp, attractive profiles, and durable factory finishes eliminate the need for periodic repainting after installation.

Aluminum conducts heat so rapidly, however, that unless an aluminum frame is constructed with a thermal break made of plastic or synthetic rubber components to interrupt the flow of heat through the metal, condensate and sometimes even frost will form on interior frame surfaces during cold winter weather. Aluminum windows are also more costly than wood or plastic windows. The majority of commercial and institutional windows, as well as many residential windows, are framed with aluminum (Figures 18.8–18.11). Aluminum frames are usually anodized or permanently coated, as described in Chapter 21.

Figure 18.8 The details of this commercial-grade double-hung aluminum window are keyed to the numbers on the small elevation view at the upper left. Cast and debridged thermal breaks, which are shown on the drawings as small white areas gripped by a “claw” configuration of aluminum on either side, separate the outdoor and indoor portions of all the sash and frame extrusions. Pile weatherstripping seals against air leaks at all the interfaces between sashes and frame. For help in understanding the complexities of aluminum extrusions, see Chapter 21. (Courtesy of Kawneer Company, Inc.)

Figure 18.9 Two aluminum double-hung window units in back, with an aluminum sliding window in front. (Courtesy of Kawneer Company, Inc.)

Figure 18.10 A cutaway sample of a standard cast and debridged plastic thermal break in an aluminum window frame. (Photo by Joseph Iano.)

Figure 18.11 A sample of quadruple glazing in a high-thermal-performance aluminum frame. The glazing consists of two outer lites of ¼-inch (6-mm) glass and two inner plastic films, to create three airspaces within the unit. The exterior lite and the innermost film both have low-emissivity coatings. The metal foil vapor barrier in the warm edge spacer is also visible. The aluminum frame thermal break is made from two strips of polyamide plastic filled with glass fiber insulation between the strips. This window can achieve an overall thermal performance of approximately U-0.13 (U-0.75 metric). For comparison with other common window types, see Figure 18.21. (Photo by Joseph Iano.)

Plastics

Plastic window frames, though relatively new, now account for more than half of all windows sold in the U.S. residential market. Plastic windows never need painting, and they are fairly good thermal insulators. Many also cost less than wood or clad wood windows. The disadvantages of plastics are that they are not as stiff or strong as other window materials and they have very high coefficients of thermal expansion (Figure 18.12). The most common material for plastic window frames is polyvinyl chloride (PVC, vinyl), which is formulated with a high proportion of inert filler material to minimize thermal expansion and contraction. Some typical PVC window details are shown in Figures 18.13, 18.14, and 18.15. For a discussion of concerns regarding the environmental and health effects of PVC, see the sidebar on plastics later in this chapter.

Figure 18.12 A comparison of the coefficients of thermal expansion of wood, glass-fiber-reinforced plastic (GFRP), aluminum, and vinyl. Vinyl expands 15 times as much as wood, 8 times as much as GFRP, and 3 times as much as aluminum. Units on the graph are in./in./°F × 10−6 on the left of the vertical axis and mm/mm/°C × 10−6 on the right.

Figure 18.13 Comparative details of a single-hung residential window with an aluminum frame (left) and a double-hung residential window with a PVC plastic frame (right). The small inset drawing at the top center of the illustration shows an elevation view of the window with numbers that are keyed to the detail sections below. The comparatively thick sections of plastic are indicative of its lesser stiffness in comparison to aluminum. The diagonally hatched areas of the aluminum details are plastic thermal breaks. The inherently low thermal conductivity of the PVC and the multichambered construction eliminate the need for thermal breaks in the plastic window. (Reprinted with permission from AAMA Aluminum Curtain Wall Design Guide.) You can download a PDF of this figure at http://www.wiley.com/go/aflblce6ne.

Figure 18.14 Cutaway sample of a plastic double-hung window with double glazing and an external half-screen. (Courtesy of Vinyl Building Products, Inc.)

Figure 18.15 For ease of washing the exterior surfaces of the glass, the sashes of this plastic window can be unlocked from the frame and tilted inward. (Courtesy of Vinyl Building Products, Inc.)

Glass-fiber-reinforced plastic (GFRP) windows, frequently referred to as fiberglass windows, are the newest product in the window market. GFRP frame sections are produced by a process of pultrusion: Continuous lengths of glass fiber are pulled through a bath of plastic resin, usually polyester, and then through a shaped, heated die in which the resin hardens. The resulting sash pieces are strong, stiff, and relatively low in thermal expansion. Like PVC, they are fairly good thermal insulators. However, GFRP windows are more expensive than those made of wood or plastic.

The thermal performance of both vinyl and GFRP window frames can be enhanced with foam insulation injected into the hollow spaces within the frame sections.

Dietz, Albert G. H. Plastics for Architects and Builders. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 1969.

Despite its age, this deservedly famous little book is still the best introduction to the subject for building professionals.

Hornbostel, Caleb. Construction Materials: Types, Uses and Applications (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1991.

The section on plastics of this monumental book gives excellent summaries of the plastics most used in buildings.

Figure A Polystyrene.

Figure B A silicone.

Figure C Polyvinyl chloride (PVC).

Figure D High-impact polystyrene.

Figure E High-density polyethylene.

Figure F Low-density polyethylene.

Some Synthetic Rubbers Used in Construction

| Chlorinated polyethylene, chlorosulfonated polyethylene (Hypalon) | Roof membranes |

| Ethylene-propylene-diene monomer (EPDM) | Roof membranes, flashings |

| Isobutylene-isoprene copolymer (butyl rubber) | Flashings, waterproofing |

| Polychloroprene (Neoprene) | Gaskets, waterproofing |

| Polyisobutylene (PIB) | Roof membranes |

| Polysiloxane (silicone rubber) | Sealants, adhesives, coatings, roof membranes |

| Polyurethanes | Sealants, insulation, coatings |

| Sodium polysulfide (polysulfide, thiokol) | Sealants |

Some Plastics Used in Construction

Steel and Bronze

The chief advantage of steel (and to some extent bronze) as a frame material for windows is its strength, which permits steel sash sections to be slenderer than those of wood and aluminum (Figures 18.16 through 18.20). Steel windows may be made of steel coated in the factory with a long-lasting paint coating, galvanized steel, or stainless steel, depending on requirements for durability and appearance. Bronze windows are made in configurations similar to those for steel, usually with a natural patina finish. Steel and bronze are both less conductive of heat than aluminum, so windows made of these metals are less prone to forming condensation in cold weather. Where improved thermal performance is required, thermal break systems are also available.

Figure 18.16 Samples of hot-rolled steel window frame sections, non-thermally broken. The nearest sample includes a snap-in aluminum bead for holding the glass in place. (Steel windows by Hope's; Hope's photography by David Moog.)

Figure 18.17 Cutaway sample of a non-thermally broken steel-framed window with aluminum glazing beads and factory finish. (Steel windows by Hope's; Hope's photography by David Moog.)

Figure 18.18 Cutaway section through a thermally broken, stainless steel window frame, with double glazing. Note how exterior steel components (left-hand side in photo) are separated by plastic thermal breaks or other low-density materials from steel parts on the inside (right-hand side). (Photo by Joseph Iano.)

Figure 18.19 Exterior detail view of the thermally broken stainless steel window frame seen in Figure 18.18. At bottom right is a fixed window unit, above that is an operable unit, and to the left is a door. (Photo by Joseph Iano.)

Figure 18.20 The narrow sight lines of steel windows and doors are evident in this photograph. (Steel windows by Hope's; Hope's photography by David Moog.)

Muntins

In earlier times, because of the difficulty of manufacturing large sheets of glass that were free of significant defects, windows were necessarily divided into small lites by muntins, thin wooden bars in which the glass was mounted within each sash. (The upper sashes in Figure 18.6 have muntins.) A typical double-hung window had its upper sash and lower sash each divided into six lites and was referred to as a six over six. Muntin arrangements changed with changing architectural styles and improvements in glass manufacture. Today's windows, glazed with large, virtually flawless lites of glass, need no muntins at all, but many building owners and designers prefer the look of traditional muntined windows. This desire for muntins is greatly complicated by the necessity of using insulated glazing to meet energy conservation code requirements. Some manufacturers offer the option of individual small lites of double glazing held in deep muntins. This is relatively expensive, and the muntins tend to look thick and heavy. The least expensive option utilizes grids of imitation muntin bars, made of wood or plastic, that are clipped into each sash against the interior surface of the glass. These are designed to be removed easily for washing the glass. Other alternatives are imitation muntin grids between the sheets of glass, which are not very convincing replicas of the real thing; and grids, either removable or permanently bonded to the glass, on both the outside and inside faces of the window. Another option is to use a primary window with authentic divided lights of single glazing and to increase its thermal performance with an outer storm sash or other secondary window with improved thermal performance. Of all the options, this one looks best from the inside, but reflections in the outer sash or window largely obscure the muntins from the outside.

Glazing

Single glazing is acceptable only in the mildest of climates, because of its low resistance to heat flow and the likelihood that moisture will condense on its interior surface in cool weather. Double glazing is the minimum permitted by energy codes in most climate zones. Where low-e coatings, dense gas fills, and thermally improved spacers were once considered exotic, high-performance options, these features are now becoming increasingly common in standard window units, especially as energy codes continue to raise thermal efficiency standards. And even higher-performing systems, with triple and quadruple glazing, are becoming increasingly available.

Figure 18.21 lists thermal transmittance properties for some example combinations of window frame and glazing options. The listed U-Factors are overall values for complete window assemblies, accounting for differences in the thermal properties of the center of glass, edge of glass, and frames. When selecting actual windows, whole-window U-Factors for the particular window are provided by the window manufacturer as determined by laboratory testing or computer simulation. In addition to thermal transmittance, solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) and visible light transmittance (VT) are other important measures of a window system's performance. See Chapter 17 for a discussion of these properties.

Figure 18.21 Comparative U-Factors for various window frame and glazing combinations. Lower values correspond to better thermal performance. Note that frame material has a significant impact on the performance of the overall window assembly. Very high performance windows, with even lower overall U-factors (approximately 0.1 Btu/ft2-hr-oF or 0.6 W/m2-oK) are available from some manufacturers. See Chapter 17 for a more in-depth discussion of glazing types.

Installing Windows

Some catalog pages for windows are reproduced in Figures 18.22, 18.23, and 18.24 to give an idea of the information on window configurations that is available to the designer. Important dimensions given in catalogs are those of the rough opening and masonry opening. The rough opening height and width are the dimensions of the hole that must be left in a framed wall for installation of the window. They are slightly larger than the corresponding outside dimensions of the window unit itself, to allow the installer to locate and level the unit accurately and to ensure that the window unit is isolated from structural stresses within the wall system. The masonry opening dimensions indicate the size of the hole that must be provided if the window is mounted in a masonry wall.

Figure 18.22 Manufacturer's catalog details for an aluminum-clad, wood-framed casement window with double glazing and an interior insect screen. (Courtesy of Marvin Windows & Doors.)

Figure 18.22 (Continued)

Figure 18.23 One of several pages in a manufacturer's catalog that show stock sizes and configurations of aluminum-clad wood casement windows. (Courtesy of Marvin Windows & Doors.) You can download a PDF of this figure at http://www.wiley.com/go/aflblce6ne.

Figure 18.23 (Continued)

Figure 18.24 These fixed windows are sized to match stock sizes of casement windows by the same manufacturer, allowing the designer to mix and match. (Courtesy of Marvin Windows & Doors.) You can download a PDF of this figure at http://www.wiley.com/go/aflblce6ne.

A rough opening or masonry opening should be flashed carefully before the window is installed to avoid later problems with leakage of water or air (for example, Figures 6.13 through 6.15). Adhesive-backed window flashing materials or sheet metal are the commonly used materials. Adhesive-backed flashings may be made of rubberized asphalt, similar in composition to the rubberized roof underlayment frequently used along the eaves of the roof (described in Chapter 7), reinforced plastic, or synthetic fibers designed for compatibility with proprietary building wrap products. Metal used for flashings must be corrosion resistant.

Most factory-made windows are easy to install, often requiring only a few minutes per window. Windows that are framed or clad in aluminum or plastic are usually provided with a continuous flange around the perimeter of the window unit. When the unit is pushed into the rough opening from the outside, the flange bears against the sheathing along all four edges. After the unit has been located and plumbed (made level and square) in the opening, it is attached to the frame by means of nails driven through the flanges. Then all the edges of the flanges should be made airtight, as shown in Figure 6.13. The flanges are eventually concealed by the exterior cladding or trim.

Methods for anchoring window units into masonry walls vary widely, from nailing the unit to wood strips that have been fastened inside the masonry with bolts or powder-driven fasteners to attaching the unit to steel clips that have been laid into the mortar joints of the masonry. The window manufacturer's recommendations should be followed in each case.

- According to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, solar heat gain and wintertime heat losses through windows account for roughly 30 percent of U.S. building heating and cooling electrical loads.

- In addition to the thermal properties of the glass in a window, the thermal conductivity of the frame and the air leakage of the window or door unit have very significant effects on the amount of energy that will be required to heat and cool the building.

- Doors can leak significant quantities of heat by conduction through the material of the door. Foam-core doors have better thermal performance than other types. The performance of any exterior residential door can be improved substantially by adding a storm door during the cold season of the year. Airlock vestibules can limit the amount of outdoor air that enters a building when the exterior door is open, as well as improve the comfort of building occupants in the vicinity of the vestibule. Revolving doors, which maintain an air seal regardless of their position, are suitable alternatives to vestibules. All doors should be tightly weatherstripped to limit loss of conditioned air.

- With respect to frame materials:

- Issues of sustainability of wood production are covered in Chapter 3. When a building with wood windows is demolished, the windows are generally sent to landfills or incinerators and are not recycled.

- Aluminum frames must be thermally broken for the sake of energy efficiency. They are often recycled during demolition and should be recycled in every case. Chapter 21 discusses sustainability issues relating to the material aluminum itself.

- PVC window frames are thermally efficient. They can be recycled during demolition, and a significant percentage is being recycled at present. However, sustainability programs, such as LEED and the Living Building Challenge, discourage the use of PVC in buildings due to concerns over this material's environmental and health effects.

- Steel window and door frames are made from recycled steel and can be recycled again when a building is demolished. Their thermal performance is moderate and can be improved greatly by the insertion of thermal breaks.

DOORS

Doors fall into two general categories, exterior and interior. Weather resistance is usually the most important functional factor in choosing exterior doors, whereas resistance to the passage of sound or fire and smoke are frequently important criteria in the selection of interior doors. Many different modes of door operation are possible (Figure 18.25).

Figure 18.25 Some modes of door operation.

Figure 18.25 (Continued)

Figure 18.25 (Continued)

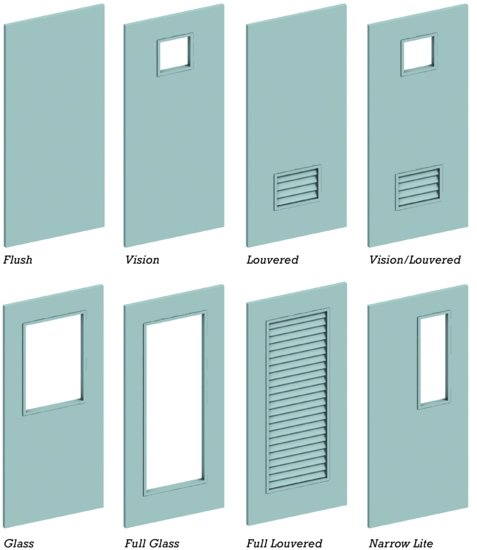

There are numerous types of exterior doors: solid entrance doors, entrance doors that contain glass, storefront doors that are mostly or entirely made of glass, storm doors, screen doors, vehicular doors for residential garages and industrial use, revolving doors, and cellar doors, to name just a few. Interior doors come in dozens of additional types. To simplify our discussion, we will focus on swinging doors for both residential and commercial use.

Wood Doors

At one time, nearly all doors were made of wood. In simple buildings, primitive doors made of planks and Z-bracing were once common. In more finished buildings, stile-and-rail doors gave a more sophisticated appearance while avoiding the worst problems of moisture expansion and contraction to which plank doors are subject (Figures 7.23 and 7.24; Figure 18.26). The panels are not glued to the stiles and rails, but instead “float” in unglued grooves that allow them to move. The doors may be made of solid wood or of wood composite materials with veneered faces and edges. In either case, they are available in many different species of woods.

Figure 18.26 Some typical configurations for wood doors. The top row consists of flush doors. The middle row is made up of stile-and-rail doors.

Figure 18.26 (Continued)

Figure 18.26 (Continued)

In recent decades, stile-and-rail doors have continued to be popular in higher-quality buildings. However, flush doors have captured the majority of the market, chiefly because they are easier to manufacture and therefore less costly. For exterior use in small buildings, and for both exterior and interior use in institutional and commercial buildings, flush doors are constructed with a solid core of wood blocks or wood composite material (Figure 7.24). Interior doors in residences often have a hollow core. These consist of two veneered wood faces that are bonded to a concealed grid of interior spacers made of paperboard or wood. The perimeters of the faces are glued to wood edge strips. Flush doors with wood faces are also available with a solid mineral core that allows them to perform as fire doors.

Most flush wood doors are manufactured and specified according to the Window and Door Manufacturers ANSI/WDMA I.S.1-A-04 Architectural Wood Flush Doors. This standard addresses door appearance and durability, and includes three performance grades—Standard Duty, Heavy Duty, and Extra Heavy Duty—intended for doors used in applications of increasingly heavy usage. High-quality wood doors, especially those custom made in the woodworker's shop, can also be made to the Architectural Woodworking Institute standard Architectural Woodwork Standards, a comprehensive manual of materials and methods for custom woodwork.

A relatively recent development is a door made of wood fiber composite material that is pressed into the shape of a stile-and-rail door. Usually, the faces of the door may be given an artificial wood grain texture or faced with real wood veneer.

Entrance doors must be well constructed and tightly weatherstripped if they are not to leak air and water. Properly installed and finished wood panel or solid-core doors are excellent for exterior residential use (Figures 6.16, 6.17). Pressed sheet metal doors and molded GFRP doors, usually embossed to resemble wood stile-and-rail doors, are popular alternatives to wood exterior residential doors. Their cores are filled with insulating plastic foam, making their thermal performance superior to that of wood doors. They do not suffer from moisture expansion and contraction, as wood doors do. They are often furnished prehung, meaning that they are already mounted on hinges in a surrounding frame, complete with weatherstripping, ready to install by merely nailing the frame into the wall. Wood doors can also be purchased prehung, although many are still hung and weatherstripped on the building site. The major disadvantage of metal and plastic exterior doors is that they do not have the satisfying appearance, feel, or sound of a wood door.

Residential entrance doors almost always swing inward and are mounted on the interior side of the door frame. This makes them less vulnerable to thieves who would remove hinge pins or use a thin blade to push back the latch to gain entrance. In cold climates, it also prevents snow that may accumulate against the door from preventing the door from opening. For improved wintertime thermal performance of the entrance, a storm door may be mounted on the outside of the same frame, swinging outward. The storm door usually includes at least one large panel of tempered glass.

In summer, a screen door may be substituted for the storm door. A combination door, which has easily interchangeable screen and storm panels, is more convenient than separate screen and storm doors.

Steel Flush Doors

Flush doors with faces of painted sheet steel, called hollow metal doors, are the most common type of door in nonresidential buildings (Figure 18.27). For economy, interior steel doors in many situations have hollow cores. Solid-core doors are required for exterior use and in situations that demand increased fire resistance, more rugged construction, or better acoustical privacy between rooms.

Figure 18.27 Some typical configurations for steel doors.

Metal doors and most nonresidential wood doors are usually hinged to steel frames called hollow metal frames (Figure 18.28). Knocked down (KD) steel frames arrive on the construction site in three separate sections for the two jambs and head, and are assembled in place into the previously prepared wall opening. Welded steel frames arrive on the construction site preassembled and welded at the corners. When used with gypsum-faced partitions, these frames must be erected before the wall, because of the way in which the frame overlaps with the adjacent wall surfaces. Welded steel frames are also stronger than KD frames and the absence of any visual seam at the frame corners is frequently considered more attractive. Where hollow metal door frames are installed within masonry walls, they may be filled with cementitious grout to improve sound deadening and to make the door frame more resistant to tampering or forced entry. As an alternative to hollow metal, frames of wood or aluminum can also be used.

Figure 18.28 Details of hollow steel door frames. The lettered circles on the elevation at the upper left correspond to the details on the rest of the page. You can download a PDF of this figure at http://www.wiley.com/go/aflblce6ne.

The sheet metal used in the manufacture of hollow metal doors and frames can be varied in thickness, to achieve varying levels of durability. Where corrosion resistance is a concern, galvanized steel or stainless steel may be used in place of ordinary steel.

Standard steel doors and frames are manufactured and specified according to the Steel Door Institute's ANSI/SDI A250.8 Recommended Specifications for Standard Steel Doors and Frames. Custom, high-quality hollow metal doors and frames follow the Hollow Metal Manufacturers Association's ANSI/NAAMM-HMMA 861 Guide Specifications for Commercial Hollow Metal Doors and Frames.

Fire Doors

Fire doors have a noncombustible mineral core and are rated according to the period of time for which they are able to resist specified time and temperature conditions, as defined by NFPA 252 Standard Methods of Fire Tests of Door Assemblies, or several similar tests defined by Underwriters Laboratories. In general, doors within fire resistance-rated walls must themselves also be fire rated. However, because doors constitute only a limited area of most walls, and because combustible furnishings or materials are not normally located directly in front of door openings, the required fire resistance rating for fire doors is often less than that required for the walls in which they are located. Figure 18.29 gives fire resistance ratings for fire doors as required by the International Building Code (IBC). For example, a door in a 2-hour rated exit stairway enclosure must be 1½-hour rated, a door in a 1-hour rated exit stairway enclosure must be 1-hour rated, and a door in a 1-hour rated exit corridor must be 20-minute (1/3-hour) rated. Doors in walls that are 2-, 3-, and 4-hour fire resistance rated, such as those separating uses within a building or separating buildings from one another, must be 1½- or 3-hour rated. A standardized label is permanently affixed to the edge of each fire door at the time of manufacture to designate its degree of fire resistance. (The building code requires that these labels not be painted over during construction so that the fire rating of the door can always be verified during subsequent building inspections.)

Figure 18.29 Required fire resistance ratings for doors, according to the International Building Code. (Part of Table 716.5; Excerpted from the 2012 International Building Code, Copyright 2011. Washington, D.C.: International Code Council. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. www.ICCSAFE.org)

Glass used in fire doors must itself be fire rated (see Chapter 17) so that it will not break and fall out of the opening for a specified length of time when exposed to the heat of fire. The maximum size of glass may also be restricted, depending on the fire classification of the door and the type of rated assembly into which it is installed. Like glass in any door, glass in fire doors must meet the requirements of safety glazing so that if broken, it does not create dangerous shards.

Egress Doors and Accessible Doors

Many doorways act as components of a building's egress system, the path that occupants take when exiting a building during a fire or other emergency. Building codes require that such doorways be sufficiently wide to allow occupants to exit in a timely manner, with the width of any particular door dependent on the number of occupants served. For ease of operation, most egress doors must be side-hinged; they must not be too large; and when equipped with closers, they must not require too much force to swing open. The International Building Code requires egress doors serving 50 or more building occupants, as well as doors serving Hazardous Occupancy spaces, to swing in the direction of egress travel so that they do not become impediments to occupants attempting to exit quickly. Even when locked, egress doors must remain readily openable from the side from which occupants may approach the door when exiting. To ensure the simplest possible operation under emergency conditions, some egress doors are required to be fitted with panic hardware, horizontal bars or similar devices installed across the face of the door that unlock and unlatch the door whenever the bar is depressed.

Doorways along buildings routes that must be accessible to persons with disabilities must meet requirements for minimum width, ease of operation, maximum height of sill, and adequate clearance for approaching and opening the door.

There are many types of special-purpose doors. Among the most common are X-ray shielding doors, which contain a layer of lead foil; electric field shielding doors, with an internal layer of metal mesh that is electrically grounded through the hinges; heavily insulated cold storage doors; and bank vault doors.

Door Hardware

Unlike windows, in which operating hardware is selected by the manufacturer and installed in the factory, most door hardware is selected by the designer independently from the door itself, and installed on the construction site. Every door requires at least some hardware to control its motion and the means by which occupants manipulate it. Swinging doors are usually hung with two, three, or four butt hinges, depending on their weight. Each hinge consists of two leafs, one attached to the edge of the door and the other to the frame, and joined by a pin around which the leafs rotate. For door operation, either a round door knob or flatter lever is provided, located a little below mid-height of the door and close to the swinging edge of the door. Knobs are frequently used in residential occupancies, but wherever accessibility is a concern, levers that are more universally operable must be used. The knob or lever controls a latch in the door edge, disengaging it from the mating strike in the door frame and allowing the door to be swung open.

Depending on the functional requirements of the door, a bewildering array of additional hardware choices may be made, including, for example, locking and keying mechanisms to secure a door when closed, closing and opening devices to automate or provide assistance in door operation, stops mounted to walls or floors to limit door swing, silencers (small cushions) attached to the door frame that reduce door closing noise, viewers to see through a door, knockers, thresholds to manage transitions between materials on either side of the door, weatherstripping to control the flow of air and water around the door edges, soundstripping to control the passage of sound, kick plates to protect the door from damage, electronic interfaces with building communications and controls, and more. All of these come in various styles and operational configurations. Hardware can also be specified to differing levels of durability and with many different finishes. On larger projects, hardware specification is frequently performed by a consultant with specialized knowledge in these areas.

OTHER WINDOW AND DOOR REQUIREMENTS

Safety Considerations in Windows and Doors

To prevent accidental breakage and injuries, building codes require glass within doors, and large lites within windows that are near enough to the floor or to doors to be mistaken for open doorways, to be made of breakage-resistant material. Tempered glass is most often used for this purpose, but some laminated glass and plastic glazing sheets can also meet the necessary requirements. For more information, see the discussion of safety glazing in Chapter 17.

In residences, buildings codes require at least one emergency escape and rescue opening in each bedroom, consisting of either a door to the exterior or a window that can be opened to an aperture large enough to permit occupants of the bedroom to escape through it and firefighters to enter through it. In the International Building Code, where a window is used for this purpose, it must have a net clear opening area of at least 5.7 square feet (0.53 m2), a clear width of at least 20 inches (510 mm), a clear height of at least 24 inches (610 mm), and no sill higher than 44 inches (1.12 m) above the floor.

Where operable windows in apartments, residential dwelling units, and similar residential occupancies are more than 6 feet (1829 mm) above the exterior finished grade, the International Building Code requires that they be designed to minimize the risk of a child accidentally falling through them. Such windows must have sills not less than 36 inches (610 mm) above the interior finish floor. Where glazing is closer to the floor, the window unit must fixed, it must have openings sufficiently limited in size that a 4-inch (102-mm)-diameter sphere cannot pass through, or it must be protected with guards or other fall prevention devices.

Casement and awning windows should not be used adjacent to porches or walkways, where someone might be injured by running into the projecting sash. Similarly, inswinging windows should not be used in corridors unless they are above head level.

Structural Performance and Resistance to Wind and Rain

The performance of windows and exterior doors is defined by the Standard/Specification for Windows, Doors, and Unit Skylights, jointly published by the American Architectural Manufacturers Association (AAMA), the Window and Door Manufacturers Association (WDMA), and the Canadian Standards Association (CSA), officially designated as AAMA/WDMA/CSA 101/I.S.2/A440. This specification establishes minimum requirements for air leakage, water penetration, structural strength, operating force, and forced-entry resistance of aluminum, plastic, and wood-framed windows, doors, and unit skylights.

The AAMA/WDMA/CSA Standard/Specification uses a letter designation called Performance Class and a numeric designation called Performance Grade to indicate the minimum capabilities of fenestration products. Performance Classes, in order of increasing capability, are R, LC, C, HC, and AW. In previous editions of the standard, these letter designations were associated with the terms “residential,” “light commercial,” “commercial,” “heavy commercial,” and “architectural,” respectively. Although these plain word descriptions have been removed from newer versions of the standard, knowledge of them is still helpful in recalling the intended ranking of the letter designations themselves. Each Performance Class sets criteria for resistance to wind loads, resistance to water penetration, and maximum air leakage.

Numeric Performance Grades correspond to maximum design wind pressures. For example, Grade 30 indicates a unit suitable for design wind pressures up to 30 psf (1440 Pa). Grades are specified starting at 15 psf (720 Pa) and increasing in increments of 5 psf (240 Pa). Each Class has a minimum acceptable Grade, and higher than minimum Grades can be specified where resistance to higher wind forces is required.

An example of a manufacturer's complete tested product designation is Class R—PG30: Size tested: 760 × 1520 mm (~30 × 60 in)—Casement, where R is the Performance Class; 30 is the Performance Grade; the pairs of numbers indicate the maximum size of the tested unit that meets these criteria, expressed as width by height, first in millimeters and then, in parentheses, in inches; and finally, the type of window as a casement. In practice, the designer may choose a Performance Class based on the building type and general expectations for durability of the system. For example, a Class LC window may be specified for a low-rise multifamily building, a Class HC window for a hospital or school, or a Class AW window for a large institutional or high-rise building. The required Performance Grade should be determined based on the design wind pressures acting on the building, information that is usually provided by the structural engineer.

Thermal Performance

With regard to energy efficiency, the National Fenestration Rating Council (NFRC) defines a program of testing and labeling based on two standards: NFRC 100 Procedure for Determining Fenestration Product U-Factors, and NFRC 200 Procedure for Determining Fenestration Product Solar Heat Gain Coefficient and Visible Transmittance at Normal Incidence. The two most important properties included in these standards are thermal transmittance (U-Factor) and solar heat gain coefficient, both of which directly affect building energy consumption and are regulated by energy codes. Importantly, U-Factors represent the overall thermal transmittance, or whole product heat loss, of complete window, door, and skylight products. That is, they account for the combined contributions to thermal transmittance of the center of glass, edge of glass, framing, and other components. Visible light transmittance, air leakage, and condensation resistance ratings may also be included in NFRC ratings. An example of a standard label that is affixed to each NFRC-rated window is shown in Figure 18.30.

Figure 18.30 A sample NFRC certification label that is affixed to a window unit so that buyers may compare energy efficiencies.

Figure 18.31 Custom Alaskan yellow cedar wood doors on architect Steven Holl's The Chapel of St. Ignatius. (Photo by Joseph Iano.)

Figure 18.32 The Blanchard Road Alliance Church in Wheaton, Illinois, silhouettes laminated wood trusses against a wall of vinyl-clad wood frame fixed windows. (Architect: Walter C. Carlson Associates. Photo courtesy Andersen Windows, Inc. Andersen is a registered trademark of Andersen Corporation, copyright 1997. All rights reserved.)

Windows sold in the Canadian market are also given an Energy Rating (ER), a relative indicator of heating season thermal performance. The ER combines U-value, air leakage, and solar heat gain measurements into a single number indicating net heat loss (negative ER) or heat gain (positive ER) over a defined set of conditions. ERs may be used to compare the relative thermal efficiency of windows, with a higher (or more positive) ER indicating better thermal performance than a window with a lower (or more negative) ER.

The AAMA/WDMA/CSA and NFRC standards are referenced by the International Building Code and National Building Code of Canada, making them the de facto standards for the selection of most North American building fenestration products.

Impact Resistance

Buildings in hurricane-prone regions can be subject to extremely powerful and destructive winds, and glazed openings in such buildings are especially vulnerable. The pressure of high-speed winds can cause glass to break, or it can suck whole lites out of their sashes, whole sashes out of their surrounding frames, or whole frames out of their rough openings. Glass can also be broken by rocks, severed tree limbs, and other debris launched by the wind with missile-like force. Once openings in a building are breached, the force of the wind can, in extreme cases, literally blow the roof off a structure. Even where a building structure remains intact, failed openings can admit large amounts of rainwater that can severely damage the building and its contents.

In the International Building Code, glazed openings in wind-borne debris regions must meet special standards for resistance to high wind forces and debris impact. These regions include portions of the U.S. Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico coasts, the islands of Hawaii, and certain other U.S. territorial islands that are frequently subjected to hurricane-force winds. In these regions, most glazed openings must meet the requirements of two tests, ASTM E1996 and E1886, which subject assemblies to airborne “missiles” and cyclical air pressures to determine their ability to remain in place under hurricane-like conditions. The testing can be quite dramatic. For windows destined for installed locations not more than 30 feet (9.1 m) above grade, a 9-pound, roughly 8-foot-long (4.1 kg, roughly 2.4 m long) 2 × 4 is fired endwise toward the window from a special cannon at a speed of 34 mph (55 kph). Although the glass is permitted to crack, it must survive in place, without being penetrated by the wood member.

Such impact-resistant openings (also sometimes referred to as hurricane-rated openings) are fitted with laminated glass with a heavy interlayer of PVB or other similarly tough, viscous plastic. They also have stronger glazing (gasketing) systems to better hold the glass units in place, their frames are structurally reinforced, and they are fastened into their rough openings with extra-strong attachment hardware. As an alternative to providing impact-resistant openings in one- and two-story buildings, the code permits the use of precut plywood or OSB panels that can be fastened into place over the outside of such openings when needed to act as temporary storm shutters.

Blast Resistance

In buildings subject to special security requirements, windows, curtain walls, and other glazing may be designed for resistance to the force of explosive blasts. Two federal standards for such blast-resistant glazing systems are in place, one published by the GSA/Interagency Committee Security Design Criteria and the other by the U.S. Department of Defense.

Design for blast resistance involves defining the size of the blast and its distance from the glazing system, as well as the glazing system's response to the blast. Of particular concern is the extent to which glass remains intact within the assembly or to which it shatters and disperses as hazardous fragments that could injure building occupants. Like impact-resistant glazing, blast-resistant glazing typically relies on laminated glass and reinforced framing and attachment systems.

KEY TERMS

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. List in detail the primary functional requirements for windows in each of the following situations:

a. A residential bathroom in an urban apartment building

b. A jail cell

c. A display window in a department store

d. A teller's window in a drive-in banking facility

e. A bedroom in Nome, Alaska

f. A living room in Hilo, Hawaii

2. Select a type of window operation for each of the following situations:

a. A window that can be left open in the rain

b. A window that must induce the maximum possible ventilation from passing breezes

c. A window in a high-rise office building

d. A window to frame an expansive view of distant mountains

e. A window that can be operated as either a casement or a hopper

3. Compare the advantages and disadvantages of wood, plastic-clad wood, PVC, aluminum, and steel as window frame materials.

4. A well-insulated residential wall has a U-value of 0.05 and an R-value of 20 (in U.S. units). Compare the heat loss per square foot of the worst- and best-performing window and glazing combinations listed in Figure 18.21 with that of this wall.

5. Select a type of door for each of the following situations:

a. Your bedroom closet

b. A front door of a house

c. A front door of a department store

d. A door between the industrial arts shops and the cafeteria in a high school

e. A door on a warehouse loading dock

EXERCISES

1. Obtain a copy of the building code that applies to the area in which you currently live. What fire resistance ratings are required for doors in the following situations?

a. A door between a hotel room and a public corridor

b. A door in an egress stair enclosure

c. A door between an iron foundry and an office building

d. A door between a single-family residence and its attached garage

2. Obtain catalogs from several window manufacturers. From them, select a set of windows for a one-room wilderness cabin of your own design.

3. Examine closely the windows in the room in which you are now sitting. What type of glazing do they have? What type of frame? How do they operate? How are they weatherstripped? Do these windows make sense to you in terms of today's energy efficiency requirements and your own feelings about the room? How would you change them?

SELECTED REFERENCES

Carmody, John, Stephen Selkowitz, Dariush Arasteh, and Lisa Heschong. Residential Windows: A Guide to New Technologies and Energy Performance (3rd ed.). New York, W. W. Norton, 2007.

This book is a clearly written, well-illustrated introduction to considerations of energy efficiency in residential windows.

Hollow Metal Manufacturers Association. Hollow Metal Manual. Chicago, Author, various dates.

This binder includes standards for custom hollow metal doors and others useful to the designer and specifier of steel doors and frames.

Selkowitz, Stephen, Eleanor S. Lee, Dariush Arasteh, Todd Willmert, John Carmody, and Eleanor Lee. Window Systems for High-Performance Buildings. New York, W. W. Norton, 2003.

This book addresses the myriad performance requirements and selection criteria for commercial glazing and window systems.

Window & Door Manufacturers Association. Specifiers Guide to Windows and Doors. Des Plaines, IL, Author, various dates.

This compilation of documents, useful to the designer and specifier of window and door systems, includes two important standards discussed in this chapter: AAMA/WDMA/CSA 101/I.S.2/A440 and ANSI/WDMA I.S.1-A.

WEB SITES

Windows and Doors

Author's supplementary web site: www.ianosbackfill.com/18_windows_and_doors

American Architectural Manufacturers Association: www.aamanet.org

Andersen Windows: www.andersenwindows.com

Ceco Steel Doors: www.cecodoor.com

Efficient Windows Collaborative: www.efficientwindows.org

Hollow Metal Manufacturers Association: www.naamm.org/hmma

Hope's Steel Windows & Doors: www.hopeswindows.com

Impact Grade Windows (EFCO Corporation): www.impactgrade.com

Marvin Windows: www.marvin.com

National Fenestration Rating Council: www.nfrc.org

Steel Door Institute: www.steeldoor.org

Steel Window Institute: www.steelwindows.com

Whole Building Design Guide, Windows: www.wbdg.org/design/env_fenestration_win.php

Window & Door Manufacturers Association: www.wdma.com

Windows and Daylighting (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory): windows.lbl.gov

Window Systems for High-Performance Buildings (Center for Sustainable Building Research): www.commercialwindows.org