Workers complete installation of an elaborate ceiling made of gypsum board. The corners of the steplike construction have been reinforced with metal corner bead, and the joints and nail heads have been filled and sanded, ready for painting. (Courtesy of United States Gypsum Company.)

22

SELECTING INTERIOR FINISHES

Installation of Mechanical and Electrical Services

The Sequence of Interior Finishing Operations

Relationship to Mechanical and Electrical Services

Avoiding Unhealthful Materials

Trends in Interior Finish Systems

INSTALLATION OF MECHANICAL AND ELECTRICAL SERVICES

When a building has been roofed and most of its exterior cladding has been installed, its interior is sufficiently protected from the weather that work can begin on the mechanical and electrical systems. The waste lines and water supply lines of the plumbing system are installed and, if required, the pipes for an automatic sprinkler fire suppression system. The major part of the work for the heating, ventilating, and air conditioning system is carried out, including the installation of boilers, chillers, cooling towers, pumps, fans, piping, and ductwork. Electrical, communications, and control wiring are routed through the building. Elevators and escalators are installed in the structural openings provided for them.

The vertical runs of pipes, ducts, wires, and elevators through a multistory building are made through vertical shafts whose sizes and locations were determined at the time the building was designed. Before the building is finished, each shaft will be enclosed with fire-resistive walls to prevent the vertical spread of fire (Figure 22.1). Horizontal runs of pipes, ducts, and wires are usually located just below each floor slab, above the ceiling of the floor below, to keep them up out of the way. These may be left exposed in the finished building or, as is more common, hidden above suspended ceilings. Sometimes these services, especially wiring, are concealed within a hollow floor structure such as cellular metal decking or cellular raceways. Sometimes services are run between the structural floor deck and a raised access flooring system. (For a more complete explanation of these systems, see Chapter 24.) Where space is needed for supply and waste piping behind wall-mounted plumbing fixtures, double walls are constructed that readily accommodate these items.

Figure 22.1 A worker constructs a fire-resistant wall around an elevator shaft, using gypsum panels and steel C–H studs. Chapter 23 contains more detailed information on shaft walls. (Courtesy of United States Gypsum Company.)

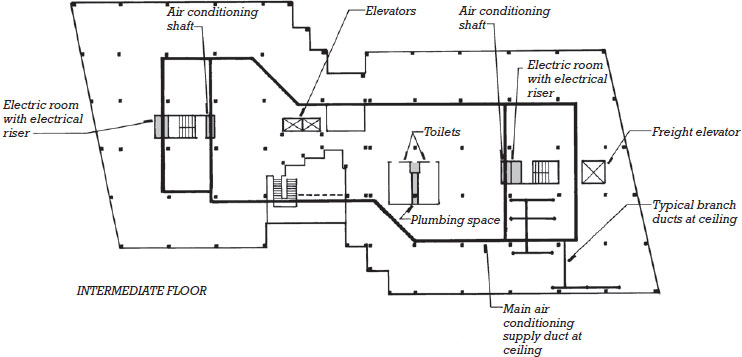

Figure 22.2 Three diagrammatic plans for an actual three-story suburban office building show the principal arrangements for plumbing, communications, electricity, heating, and cooling. Heating and cooling are accomplished by means of air ducted downward through two shafts from equipment mounted on the roof. The conditioned air from the vertical ducts is distributed around each floor by a system of horizontal ducts that run above a suspended ceiling, as shown on the plan of the intermediate floor. A row of doubled columns divides the building into two independent structures at the building separation joint to allow for differential foundation settlement and thermal expansion and contraction. (Courtesy of ADD Inc. Architects.)

Figure 22.2 (Continued)

Figure 22.2 (Continued)

Figure 22.3 Applying firestopping materials to floor penetrations. (a) Within a plumbing wall, a layer of safing insulation is cut to fit and inserted by hand into a large slab opening around a cast iron waste pipe. Then a mastic firestopping compound is applied over the safing to make the opening airtight (b). (c) Applying firestopping compound around an electrical conduit at the base of a partition. (Courtesy of United States Gypsum Company.)

(a)

(b)

(c)

Specific floor areas are reserved for mechanical and electrical functions in larger buildings (Figu re 22. 2). Distribution equipment for electrical and communications wiring and fiberoptic networks is housed in special rooms or closets. Fan rooms are often provided on each floor for air-handling machinery. In a large multistory building, space is set aside, usually at a basement or subbasement level, for pumps, boilers, chillers, electrical transformers, and other heavy equipment. At the roof are penthouses for elevator machinery and mechanical system cooling towers and ventilating fans. In very tall buildings, one or more whole floors may be set aside for mechanical equipment, and the building is zoned vertically into groups of floors that can be reached by ducts and pipes that run up and down from each of these dedicated mechanical floors.

THE SEQUENCE OF INTERIOR FINISHING OPERATIONS

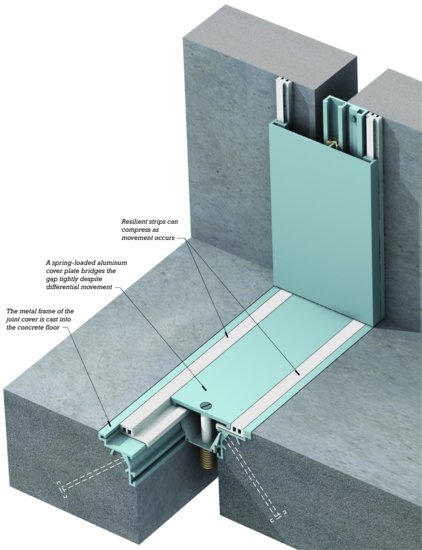

Interior finishing operations follow a carefully ordered sequence that varies somewhat from one building to another, depending on the specific requirements of each project. The first finish items to be installed are usually hanger wires for suspended ceilings, and full-height partitions and enclosures, especially those around mechanical and electrical shafts, elevator shafts, mechanical equipment rooms, and stairways. Firestopping is inserted around pipes, conduits, and ducts where they penetrate floors and fire-rated walls (Fig ure 2 2.3). The full-height partitions and enclosures, firestopping, joint covers (Figure 22.4), and safing around the perimeters of the floors constitute a very important system for keeping fire from spreading through the building.

Figure 22.4 Building separation joints must be covered on the interior of the building to make them safe, attractive, and airtight. The covers must be able to adjust readily to expected movements between the separate parts of the building. Shown here are joint covers for a floor and a wall. Both are ingeniously designed to remain tightly in place while accommodating differential movements of any type. Firestopping, to prevent the easy passage of smoke and fire from one floor to the next, not shown here, is installed behind the joint cover. For a general discussion of movement joints in buildings, see the Chapter 10 sidebar, “Movement Joints in Buildings.” (Courtesy of Architectural Art Manufacturing, Inc., Wichita, KS.)

- Finish materials that have a high recycled content reduce the demand for virgin materials and make productive use of materials that would otherwise be treated as waste. The availability of finish materials with recycled content continues to increase in many finish product categories.

- Finish materials that can be reused or recycled when they reach the end of their useful life also reduce waste. Some manufacturers, such as those of ceiling tile, carpet, and gypsum products, have established recycling or reclamation programs to divert these products from the waste stream.

- Interior finishes derived from rapidly renewable sources, such as bamboo flooring, or from certified woods reduce the depletion of raw materials of limited supply and protect forest ecosystems.

- Finish materials that are extracted, processed, and manufactured locally require less energy to transport, and their use helps to support local economies.

- Indoor finish materials and coatings present large surface areas to the interior environment of a building, making them potentially significant sources of emissions and indoor air quality problems. Potential emitters include glues and binders used in wood panels and other manufactured wood products, leveling compounds applied to subflooring, carpet fabrics and backings, carpet cushions, carpet adhesives, antimicrobial and mothproofing carpet treatments, wall covering adhesives, resilient flooring adhesives, vinyl in all its forms, gypsum board joint compounds, curtain and upholstery fabrics, paints, varnishes, stains, and more.

- Formaldehyde gas is an irritant to building occupants, causes nausea and headaches, and can exacerbate asthma. Potential sources include processed wood products, glues, adhesives, carpets, and permanent press fabrics.

- Volatile organic compounds are air pollutants; they can act as irritants, and some are significant greenhouse gases. Common emitters include processed wood products, glues, adhesives, paints and other coatings, carpets, and plastic welding processes.

- Increasingly, manufacturers are publishing emissions data for their products, offering products with reduced emissions, and participating in rating systems meeting the low-emission standards of LEED and other green building programs, making it easier for designers and specifiers to select green products.

- Mold and mildew growth in carpets, wall coverings, gypsum board assemblies, and fabrics can cause acute respiratory distress in many people. Generally, this problem occurs only when these materials are repeatedly wetted by leakage or condensation. In response to this concern, many manufacturers now offer finish materials with improved resistance to moisture and mold growth.

- Construction dust, if not fully removed before the building is occupied, can be a source of irritating particulates after occupancy.

- Floor plans that are flexible and easily adapted to new uses and partition systems that are easy to modify encourage building reuse.

- The strategic use of high ceilings, low partitions, transparency, reflective surfaces, and light colors can maximize daylighting potential and views to the exterior.

- Spaces designed with exposed structure and without suspended ceilings save materials.

After the major horizontal electrical conduits and air ducts have been installed, the grid for the suspended ceiling is attached to the hanger wires so that the lights and ventilating louvers can be mounted. Then, typically, the ceilings are finished, and framing for the partitions that do not penetrate the finish ceiling is installed. Electrical and communications wiring is brought down from the conduits above the ceilings to serve outlets in the partitions. The walls are finished and painted. The last major finishing operation is the installation of the flooring materials. This is delayed as long as possible to let the other trades complete their work and get out of the building; otherwise, the floor materials could be damaged by dropped tools, spilled paint, heavy construction equipment, weld spatter, coffee stains, and construction debris ground underfoot.

SELECTING INTERIOR FINISHES

Appearance

A major function of interior finish components is to make the interior of the building look neat and clean by covering the rougher and less organized portions of the framing, insulation, vapor retarder, electrical wiring, ductwork, and piping. Beyond this, the architect designs the finishes to carry out a particular concept of interior space, light, color, pattern, and texture. The form and height of the ceiling, changes in floor level, interpenetrations of space from one floor to another, and the configurations of the partitions are primary factors in determining the character of the interior space. Light originates from windows and electric lighting fixtures and is propagated by successive reflections off the interior surfaces of the building. Lighter-colored materials raise interior levels of illumination; darker colors and heavier textures result in a darker interior. Patterns and textures of interior finish materials are important in bringing the building down to a scale of interest that can be appreciated readily by the human eye and hand. No two buildings have the same requirements: Deep carpets and rich, polished marbles in muted tones may be chosen to give an air of affluence to a corporate lobby, brightly colored surfaces to create a happy atmosphere in a day care center, or slick plastic and highly reflective surfaces to provide a trendy ambience for the sale of designer clothing.

Durability and Maintenance

Expected levels of wear and tear must be considered carefully in selecting finishes for a building. Highly durable finishes generally cost more than shorter-lived ones and are not always required. In a courthouse, a transportation terminal, a recreation building, or a retail store, traffic is intense, and long-wearing materials are essential. In a private office or an apartment, more economical finishes are usually adequate. Water resistance is an important attribute of finish materials in kitchens, bathrooms, locker and shower rooms, entrance lobbies, and some industrial buildings. In hospitals, medical offices, kitchens, and laboratories, finish surfaces must not trap dirt and must be easily cleaned and disinfected. Maintenance procedures and costs should be considered in selecting finishes for any building: How often will each surface be cleaned, with what type of equipment, and how much will this procedure add to the cost of owning the building? How long will each surface last, and what will it cost to replace it?

Acoustic Criteria

Interior finish materials strongly affect noise levels, the quality of listening conditions, and levels of acoustic privacy inside a building. In noisy environments, interior surfaces that are highly absorptive of sound can decrease the noise intensity to a tolerable level. In lecture rooms, classrooms, meeting rooms, theaters, and concert halls, acoustically reflective and absorptive surfaces must be proportioned and placed to create optimum hearing conditions.

Between rooms, acoustic privacy is created by partitions that are both heavy and airtight. The acoustic isolation properties of lighter-weight partitions can be enhanced by additional layers of wallboard, partition details that damp the transmission of sound vibrations by means of resilient mountings on one of the partition surfaces, and sound-absorbing batts of mineral wool in the interior cavity of the partition. Manufacturers test full-scale sample partitions of every type of material for their ability to reduce the passage of sound between rooms in a procedure outlined in ASTM E90. The results of this test are converted to Sound Transmission Class (STC) numbers that can be related to accepted standards of acoustic privacy. In an actual building, however, if the cracks around the edges of a partition are not completely sealed, or if a loosely fitted door or even an unsealed electric outlet is inserted into the partition, its airtightness is compromised and its acoustical performance severely compromised. Similarly, a partition with a high STC is of little benefit if the rooms on both sides are served by a common air duct that acts incidentally as a conduit for sound, or if the partition reaches only to a lightweight, porous suspended ceiling that allows sound to pass over the top of the partition.

Transmission of impact noise from footsteps and machinery through floor–ceiling assemblies is measured according to ASTM E492, in which a standard machine taps on a floor above while instruments in a chamber below record sound levels. The results are reported as Impact Isolation Class (IIC) ratings. Impact noise transmission can be reduced by floor details that rely on soft materials that do not transmit vibration readily, such as carpeting, soft underlayment boards, or resilient underlayment matting.

Fire Criteria

Building codes devote many pages to provisions that control the materials and details for interior finishes in buildings. These requirements are aimed at several important characteristics of interior finishes with respect to fire.

Flammability and Smoke Generation

The surface burning characteristics of interior wall and ceiling finish materials are tested in accordance with ASTM E84, also called the Steiner Tunnel Test. In this test, a sample of material 20 inches wide by 24 feet long (500 × 7300 mm) forms the ceiling of a rectangular furnace into which a controlled flame is introduced at one end. The time the flame takes to spread across the face of the material from one end of the furnace to the other is recorded, along with the density of smoke developed. The results of this test are given as a flame-spread rating, indicating the rapidity with which fire will spread across a surface of a given material, and a smoke-developed rating, which classifies a material according to the amount of smoke it gives off when it burns.

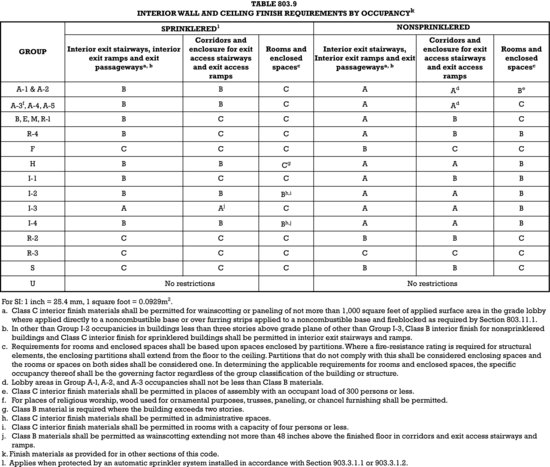

Figure 22.5 defines allowable flame-spread ratings for interior finish materials for various building occupancies according to the International Building Code. It assigns each material to one of three classes: A, B, or C. Class A materials are those with flame-spread ratings between 0 and 25, Class B between 26 and 75, and Class C between 76 and 200. (The scale of flame-spread numbers is established arbitrarily by assigning a value of 0 to cement–asbestos board and 100 to a red oak board.) For all three classes, the smoke-developed rating may not exceed 450. Materials exceeding this rating are not permitted to be used as interior finishes, because smoke, not heat or flame, is the primary killer in building fires. Interior trim materials, if their surface area does not exceed 10 percent of the total wall and ceiling area of the room, may be of Class A, B, or C in any type of building.

Figure 22.5 Flame-spread rating requirements for interior wall and ceiling finish materials, taken from the IBC. The Class ratings A, B, and C are explained in the accompanying text. (Table 803.9 excerpted from the 2012 International Building Code, Copyright 2011. Washington, D.C.: International Code Council. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. www.ICCSAFE.org) You can download a PDF of this figure at http://www.wiley.com/go/aflblce6ne.

Alternatively, interior wall and ceiling finish materials can be tested for room fire-growth contribution according to NFPA 265. In this test, the finish material is mounted to several adjacent wall and ceiling surfaces, and then (as in the Steiner Tunnel Test) subjected to a flame of controlled intensities and durations. For the material to pass, flame spread and growth must be controlled, and the quantities of heat and smoke emitted must not exceed stated limits. Materials passing this test are considered comparable to ASTM E84 Class A materials. Some materials, such as textile or expanded vinyl wall coverings, foam plastics, and combustible draperies, wall hangings, and other decorative materials, are subject to other special tests or limitations.

The combustibility of many flooring materials used in exits, corridors, and areas connected to these spaces must be tested according to NFPA 253 for minimum critical radiant flux exposure. The purpose of this test is to ensure that flooring in essential parts of the egress system cannot be easily ignited by the radiant heat of fire and hot gases in adjacent spaces. Materials must meet either Class I (most resistant to radiant heat) or Class II (moderately resistant) ratings, depending on the Occupancy and whether or not the area is protected with an automatic sprinkler system. Some traditional flooring materials, such as solid wood, resilient materials, and terrazzo, which have historically demonstrated satisfactory performance, are not required to meet this standard. In other areas of the building, flooring materials are subject to the pill test (Consumer Product Safety Commission DOC FF-1), which evaluates a material's propensity for flame spread when exposed to a burning tablet intended to simulate a dropped lit cigarette, match, or similar hazard.

Fire Resistance

Fire resistance of a wall, ceiling, or floor assembly refers not to the assembly's own combustibility, but rather to its ability to resist the passage of fire from one side of the assembly to the other. The building code regulates the fire resistance of assemblies used to protect the structure of the building, to separate various parts of a building from one another, and to separate one building from another.

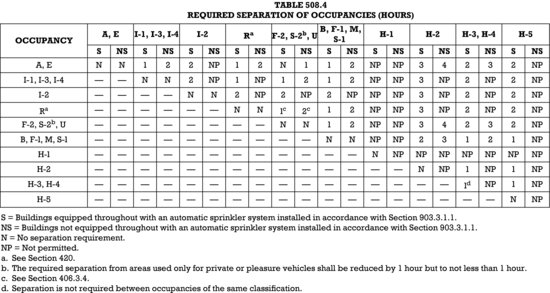

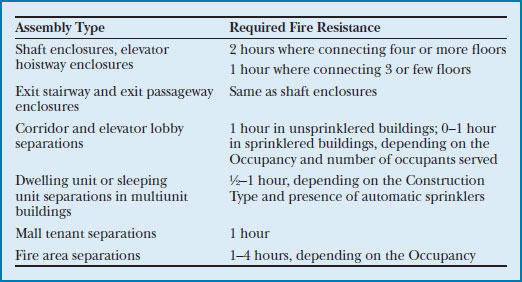

The table in Figure 22.6 specifies the required fire resistance rating, in hours of separation, between different Occupancies within the same building according to the requirements of the International Building Code. (See the figure caption for comments regarding when these requirements apply.) Fire resistance rating requirements found elsewhere in the code for separations such as shaft walls, corridors, exit enclosures, dwelling unit separations, and other nonbearing partitions, are summarized in Figure 22.7. Requirements for the protection of structure, for the fire resistance of exterior walls, and for fire walls that separate buildings are shown in Figures 1.4 and 1.7. Such requirements can be related to fire resistance information provided in manufacturers' literature similar to the examples shown in Figures 1.5 and 1.6.

Figure 22.6 IBC requirements for fire resistance ratings, in hours, for fire separation assemblies between differing Occupancies. The requirements of this table apply when occupancies are treated as separated. An alternative approach, particularly suitable to smaller buildings, allows occupancies to be nonseparated, in which case rated separations are not required. (Table 508.4 excerpted from the 2012 International Building Code, Copyright 2011. Washington, D.C.: International Code Council. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. www.ICCSAFE.org) You can download a PDF of this figure at http://www.wiley.com/go/aflblce6ne.

Figure 22.7 This table summarizes IBC fire resistance rating requirements for various types of assemblies not included in other code tables reproduced in this book. Fire areas, listed in the last row of the table, are portions of a building that are limited in area or occupant number for the purpose of determining sprinkler requirements. Some of these wall types are also discussed in greater detail in Chapter 23.

Fire resistance ratings are determined by full-scale endurance tests conducted in accordance with ASTM E119, which applies not only to partitions and walls, but also to beams, girders, columns, and floor–ceiling assemblies. In this test, the assembly is constructed in a large laboratory furnace and subjected to the structural load (if any) for which it is designed. The furnace is then heated according to a standard time–temperature curve, reaching 1700 degrees Fahrenheit (925°C) at 1 hour and 2000 degrees Fahrenheit (1093°C) after 4 hours. To achieve a given fire resistance rating in hours, an assembly must safely carry its design structural load for the designated period, must not develop any openings that permit the passage of flame or hot gases, and must insulate sufficiently against the heat of the fire to maintain surface temperatures on the side away from the fire within specified maximum levels. Wall and partition assemblies must also pass a test, called the hose stream test, intended to assess their durability while exposed to fire conditions. A duplicate sample of the assembly is subjected to half of its rated fire exposure, then sprayed with water from a calibrated fire nozzle for a specified period at a specified pressure. To pass this test, the assembly must not allow passage of the water stream.

Openings in floors, ceilings, and partitions with required fire resistance ratings are restricted in size by most codes and must be protected against the passage of fire in various ways. Doors must be rated for fire resistance in accordance with a table such as that shown in Figure 18.29. Ducts that pass through rated assemblies must be equipped with sheet metal dampers (fire dampers ) that close automatically if hot gases from a fire enter the duct. Penetrations for pipes and conduits must be sealed tightly with fire-resistive firestopping material.

As an example of the use of these tables, consider a multistory vocational high school building of Type IIA construction that includes both a number of classrooms and a woodworking shop and that is fully sprinklered. For purposes of the table reproduced in Figure 22.6, the International Building Code places classrooms in Occupancy Group E (Educational) and the shop in Occupancy G roup F-1 (Industrial, Moderate Hazard). Assuming that the building is large enough tha t the requirements of this table apply, the tw o uses must be separated from e ach other by walls (called “fire barriers”) and, if applicable, floor– ceiling assemblies, of 1-hour construction. Doors through such walls must be rated at ¾ of an hour (Figure 18.29). Figure 22.5 indicates that, in the Occupancy E portion of the building, finish materials in exit stairway enclosures must have at least a Class B rating, while Class C finish materials are permitted throughout the remainder of the building. According to Figure 22.7, walls and floor–ceiling assemblies separating corridors from adjacent spaces must have a fire resistance rating between 0 and 1 hours, and exit stairways must be enclosed in construction rated between 1 and 2 hours (the final determination of these requirements depending also on other provisions of the code). Referring to Figure 1.4, we can see that the building's structural system must be protected with 1-hour rated assemblies or, as explained in the footnotes to this table and depending on other requirements of the code, it may be permissible to leave the structure unprotected due to the presence of a sprinkler system.

Fireblocking and Draftstopping of Combustible Concealed Spaces

Building codes require that concealed hollow spaces within combustible assemblies (that is, within wood-framed walls, floors, ceilings, and roofs) be internally partitioned so that fire burning concealed within these spaces cannot rapidly spread undetected over large areas or from one floor to the next. Within combustible vertical spaces, the International Building Code requires fireblocking at every floor level; at vertical intervals of 10 feet (3 m) in tall walls; at the intersection of wall framing with floor, ceiling, and roof framing; where stair tops and bottoms meet floors; and other similar conditions. Although some of these requirements are satisfied by the top and bottom plates that are a normal part of structural framing, in other cases, additional materials are needed. Materials permitted for this use include solid lumber, plywood, OSB, particleboard, gypsum board, cement fiberboard, and even some mineral fiber and cellulose insulation products.

In a similar fashion, large, concealed, combustible horizontal spaces must be partitioned with draftstopping materials. For example, draftstopping is required in line with dwelling unit separations in multifamily structures, and in flooring, attic, and roof framing that exceed certain area limits. Specific requirements vary with building Occupancy and the presence of sprinklers. The list of materials permitted for draftstopping is similar to that for firestopping. Where the depth of a framed area is too great to easily draftstop, it may also be protected with fire sprinklers within the concealed space.

Relationship to Mechanical and Electrical Services

Interior finish materials join the mechanical and electrical services of a building at the points of delivery of the services—the electrical outlets, the lighting fixtures, the ventilating diffusers and grills, the convectors, the lavatories and water closets. Leading up to these points, the services may or may not be concealed by the finish materials. If the service lines are to be concealed, the finish systems must provide space for them, as well as for maintenance access points in the form of access doors, panels, hatches, cover plates, or ceiling or floor components that can be lifted out to expose the lines. If service lines are to be left exposed, the architect should organize them visually and specify a sufficiently high standard of workmanship in their installation so that their appearance will be satisfactory.

Changeability

How often are the use patterns of a building likely to change? In a concert hall, a chapel, or a hotel, major changes will be infrequent, so fixed, unchangeable interior partitions are appropriate. Appropriate finishes include many of the heavier, more expensive, more luxurious materials (such as tile, marble, masonry, and plaster) that are considered desirable by many building owners. In a rental office building or a retail shopping mall, changes will be frequent; lighting and partitions should be easily and economically adjustable to new use patterns without long delays or unnecessary disruption. The likelihood of frequent change may lead the designer to select either relatively inexpensive, easily removed construction such as gypsum wallboard partitions or relatively expensive but durable and reusable construction such as proprietary systems of modular, relocatable partitions. The functional and financial choices must be weighed for each building.

Cost

The cost of interior finish systems may be measured in two different ways. First cost is the installed cost. First cost is often of paramount importance when the construction budget is tight or the expected life of the investment in a building is short. Life-cycle cost takes into account not only first cost, but also the expected lifetime of the finish system, maintenance costs and fuel costs (if any) over that lifetime, replacement cost, an assumed rate of economic inflation, and the time value of money. Life-cycle cost is important to building owners who expect to retain ownership for an extended period of time. Because of its higher maintenance and replacement costs, a material that is inexpensive to buy and install may be more costly over the lifetime of a building than a material that is initially more expensive.

Avoiding Unhealthful Materials

A building's interior finish materials reside within the same environment as the building's occupants. Thus, unhealthful ingredients in these materials have the potential to readily interact with and adversely affect users of the building. For example, formaldehyde gas emitted by resins and adhesives used in some manufactured wood and other building products is a known carcinogen and irritant. A host of solvents from paints, varnishes, flooring adhesives, and other such materials, capable of a range of potential adverse health impacts, permeate the air of a building, especially when it is new. Plasticizers and stabilizers that leach from some plastics have been identified as carcinogenic, toxic, or asthma-causing. Airborne mineral and glass fibers can irritate skin, eyes, and mucous membranes. Airborne spores from molds and mildews that grow on moisture-sensitive materials can cause reactions from mild to severe in some portions of the population. On occasion, natural stone and masonry materials have been known to emit radioactive radon gas. Even ordinary construction dust can inflame respiratory passages.

Some long-recognized health hazards have been eliminated from construction materials by state or federal health regulations, and only remain a concern when encountered in older buildings. Examples include lead-containing paint; asbestos fibers in plaster, flooring, or fireproofing materials; and arsenic-containing wood preservatives. Other materials have only more recently garnered recognition as significant health concerns. In these instances, it remains incumbent upon building designers and materials specifiers to be knowledgeable of these hazards and endeavor to keep them out of buildings.

Fortunately, as awareness of these concerns has grown, the task of recognizing and avoiding unhealthful substances has become easier. For example, the Living Building Challenge Health petal includes the imperatives of Civilized Environment, ensuring access to fresh air and daylight, and Healthy Air, requiring management of indoor air quality. The Materials petal includes the Red List imperative, which identifies materials and chemicals, deemed damaging to human health or the environment, that must be excluded from the building. Similarly, the LEED rating system requires the protection of interior air quality, selection of low-emitting materials, and avoidance of known unhealthful or toxic materials. In response to initiatives such as these, there is today more data readily available to the building designer to assist in identifying and avoiding undesirable materials. And, as the construction industry responds to these market pressures, it becomes increasingly easy to find safer, appropriate alternatives.

TRENDS IN INTERIOR FINISH SYSTEMS

Interior finish systems have undergone a transformation over the past roughly 75 years. Formerly, the installation of finishes for a commercial office began with the construction of partitions of heavy clay tiles or gypsum blocks set in mortar. These were covered with two or three coats of plaster and joined to a three-coat plaster ceiling. The floor was commonly made of hardwood strips with a wood baseboard, or perhaps of poured terrazzo with an integral terrazzo base. Today, the same office might be framed in light metal studs and walled with gypsum board. The ceiling might be a separate assembly of lightweight, acoustically absorbent tiles, and the floor might be a thin layer of vinyl composition tile glued to a smooth concrete slab.

Several trends can be discerned in these changes. One is away from an integral, single-piece system of finishes toward a system made up of discrete components. In the old office, the walls, ceiling, and floor were all joined, and none could be changed without disrupting the others. In the new office, ceiling and floor finishes often extend uninterrupted from one side of the building to the other, so that partitions can be changed at will without affecting either the ceiling or the floor. The trend toward discrete components is epitomized by partitions made of modular, demountable, relocatable panels.

Another discernible trend is away from heavy finish materials to lighter ones. A partition of metal studs and gypsum board has a fraction of the weight of one of clay tiles and plaster, and a vinyl composition tile installation is many times lighter than a traditional terrazzo one of equal area. Lighter finishes reduce the dead load the structure of the building must carry. This enables the structure itself to be lighter and less expensive. Lighter finish materials reduce shipping, handling, and installation costs, and are easier to move or remove when changes are required.

“Wet” systems of interior finish, made of materials mixed with water on the building site, have been largely replaced by “dry” ones. Plaster has been replaced by gypsum board and ceiling tiles in most areas of new buildings, and tile and terrazzo floors by resilient materials or carpet. The installation of dry systems is fast and less dependent on weather conditions. Dry systems require less skill on the part of the installer than wet systems, because the skilled work is transferred from the job site to the factory, where it is done by machines. All these differences tend to result in a lower installed cost.

Traditional finishes, however, are far from obsolete. Gypsum board cannot rival three-coat plaster over metal lath for surface quality, durability, or design flexibility. Tile and terrazzo floorings are unsurpassed for wearing quality and appearance. In many situations, the life-cycle costs of traditional finishes compare favorably with those of lighter-weight alternatives whose first cost is considerably less. In addition, the aesthetic qualities of, for example, marble floors, wood wainscoting, and sculpted plaster ceilings, where such qualities are called for, cannot be imitated by any other material.

KEY TERMS

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. Draw a flow diagram of the approximate sequence in which finishing operations are carried out on a large building of Type IIA construction.

2. List the major considerations that an architect should keep in mind while selecting interior finish materials and systems.

3. What are the two major types of fire tests conducted on interior finish systems? What measures of performance are derived from each?

4. What is the difference between first cost and life-cycle cost?

EXERCISES

1. You are designing a 31-story apartment building (Occupancy R-2) in a large city. Assume that it will be fully sprinklered. What types of construction are you permitted to use under the International Building Code? What fire resistance rating will be required for the separation between the apartment floors and the retail stores on the ground floor, assuming that the different occupancy areas must be separated? What classes of finish materials can you use in the exit stairway? In the corridors to those stairways? Within the individual apartments? If a red oak board has a flame-spread rating of 100, can you panel an apartment in red oak? What fire resistance ratings are required for partitions between apartments? Between an egress corridor and an apartment? What type of fire door is required between the apartment and the exit corridor? What is the required fire resistance rating for the walls around the elevator shafts? For the purposes of this exercise, when referring to Figure 22.7, assume the highest rating requirement where a range of requirements is provided.

2. Select a compound from the Living Building Challenge Red List. Research examples of building products that contain this compound. Explain where these products are commonly used in buildings. Find products, free of Red List compounds, that may be used as alternatives.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Allen, Edward, and Joseph Iano. The Architect's Studio Companion (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006.

The fourth section of this book gives extensive information on providing space for mechanical and electrical equipment in buildings.

International Code Council, Inc. International Building Code. Falls Church, VA, Author, updated regularly.

The reader is referred to Chapters 7 and 8 of this model code, which deal with fire-resistive construction requirements for interior finishing systems.

Juracek, Judy A. Surfaces: Visual Research for Artists, Architects, and Designers. New York, W. W. Norton, 1996.

This book is a wonderful catalog of the vast expressive potential of the architectural surface, containing more than 1200 color photographs of finish surfaces of differing material types, patterns, textures, colors, and forms.

WEB SITES

Selecting Interior Finishes

Author's supplementary web site: www.ianosbackfill.com/22_selecting_interior_finishes

Greenguard Environmental Institute: www.greenguard.org

Health Product Declaration Forum: www.hpdworkinggroup.org

Healthy Building Network: www.healthybuilding.net