The first thing we have to do is to continue to keep confidence abroad in the American dollar. That means we must continue to have a balanced budget here at home in every possible circumstance that we can, because the moment that we have loss of confidence in our own fiscal policies at home, it results in gold flowing out.

—Vice President Richard Nixon, October 13, 19601

Harry Dexter White would never have been mistaken for Alexander Hamilton. An academic who joined the Treasury Department in 1934 and rose to become an assistant secretary, he was one of the world’s leading experts on, of all things, the French balance of payments between 1880 and 1913—how France had earned foreign currency for its exports, paid for its imports, and managed any difference between the two.2 In 1941, however, White was tapped by Henry Morgenthau, Jr., secretary of the treasury under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, to redesign the global economic system. This was an era of experts, of seemingly colorless men in dark suits (they were mostly men at the time) writing memos to each other and arguing about apparently arcane details that were almost entirely impenetrable to nonexperts—including their political masters. This was a long way from the grand compromises of the Constitutional Convention, the powerful rhetoric of the Federalist Papers, or any of the timeless debates involving Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson.

It was also a moment of almost unimaginable optimism. Work on planning the postwar world began within a week after the attack on Pearl Harbor; with the Pacific Fleet’s battleships sunk or damaged, the premise was still that the United States would soon become the world’s predominant market-based power.3 Who today would dare to seriously plan a new international economy, let alone think that it could actually be implemented and work? Yet the ideas produced by White and his colleagues—culminating in the Bretton Woods conference of July 1944, the Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund, and the Bretton Woods system for international payments—ended up reshaping American public finance as profoundly as anything since the debates of the 1780s and 1790s.4

The systems created by Hamilton and White both exceeded all reasonable initial expectations. Hamilton’s core principles—debt when you need it, taxes to service the debt, and fiscal responsibility as the prevailing ethos—served as the backbone of U.S. fiscal policy from 1790 through 1945, even as the world and the nature of government changed profoundly. The lessons of the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 stuck with the American political system for a long time. White’s impact, however, has been more complicated. Following the devastation of World War II, the Bretton Woods system was wildly successful as the basis for rebuilding world trade during the 1950s and 1960s and for bringing newly independent countries into the global economy. But the system contained the seeds of its own destruction, producing unsustainable trade and capital flow imbalances that could not be easily addressed within the system, leading to its collapse in the early 1970s—a moment that, to many, seemed like the end of the era of American economic predominance. But White’s core principle—that the U.S. dollar would be the world’s paramount reserve currency, offering a safe haven for all public and private investors—rose like a phoenix from the ashes of his system. The end of Bretton Woods confirmed the 1940s vision of the United States as the world’s preeminent economic power while creating the biggest credit line ever—since people and governments around the world wanted to hold American debt. It was not obvious at the time, but once politicians in Washington began to access this line of credit, it made possible a historic increase in the national debt.

To see how this happened, we need to understand how the U.S. dollar—and U.S. government debt denominated in dollars—came to supplant gold as the primary store of value in the international economic system. Gold, of course, is still alive and well as an alternative investment asset whose price springs upward whenever people worry about the ability of governments to keep inflation under control or to service their debts. But the relationship between gold and money has changed dramatically over the past three centuries, both around the world and in the United States, with important consequences for American public finance and the national debt.

What is money? Money is conventionally described as whatever people prefer to use as a store of value, a way to keep accounts, and a means for conducting transactions. A small group of people can informally agree to use anything as a way of keeping track of and settling transactions; throughout history, many transactions within stable communities have been conducted on the basis of credit.5 In modern history, however, the nature of money has been heavily influenced by government policy.6 The government decides what is “legal tender”—something that must be accepted as payment of a debt by a creditor (although businesses can reject it in everyday transactions)—and what it will accept as tax payments; both of these choices affect what ordinary people are willing to use and hold as money.7

Metal—primarily gold and silver, but also copper, brass, and other alloys—has played an important role in many monetary systems in different historical ages. In some periods, gold and silver were used as the basis for accounts and in international trade, but not as a circulating medium for ordinary transactions; in other periods, governments minted coins with small amounts of precious metals for use as currency.8 There are good reasons to use gold and silver as money. For something to serve as currency, it has to be relatively rare and relatively hard to produce; otherwise, it would be too easy for ordinary people to find or create, and would lose its value quickly. It also helps if it is durable, so it won’t break down into something else, and transportable, so it can be easily traded for goods and services. There are actually very few chemical elements that meet all of these criteria well, and gold is one of them.9 If there isn’t enough gold, however, people will use substitutes; in 1776, for example, some dollar coins were minted from pewter.10 What applies to ordinary people applies to governments as well. If currency is easy to create at very low cost—for example by stamping numbers on cheap metal or printing numbers on pieces of paper—a government that is short of precious metal will face the temptation to simply manufacture currency to pay its bills.11 This is not quite as bad as if everyone could print currency in her basement, but large volumes of new paper currency can cause rapid and accelerating inflation as more and more money chases the same amount of goods and services.

Yet sometimes the creation of paper currency may make sense. If there aren’t enough coins made from precious metals, you can have the opposite problem: too few coins chasing an increasing amount of goods and services can cause deflation (falling prices). More simply, if there isn’t enough currency to go around, it can be hard to transact business.12 A shortage of metal coin was a chronic problem in the American colonies because the British colonial authorities did not allow either the creation of a local mint or the export of coin from Britain.13 As a result, the American colonial monetary system was a complicated mélange including a Spanish-Mexican coin, widely circulating in the Caribbean, which became known in North America as the dollar.14 Necessity also encouraged the proliferation of alternative forms of money, many of which were not conducive to easy calculation:

Barter was resorted to in the earlier stages of settlement; then certain staple commodities were declared by law to be legal tender in payment of debts. Curious substitutes were employed, such as shells or wampum. Corn, cattle, peltry, furs were monetary media in New England; tobacco and rice in the South. . . . One student, later president of [Harvard] college, settled his bill with “an old cow.”15

At the same time, the unit of account was British pounds, shillings, and pence, but different colonies set different exchange rates between currencies, with the British authorities also weighing in. None of this worked well and the overall monetary situation was confused, to put it mildly.16

In this context, adding to the supply of ready money with some decorative government-authorized paper was not a crazy idea.17 As an economy develops, the total volume of goods and services grows, which increases the demand for money to finance transactions. Adding more money to the economy can be a good thing, so long as the supply of new money remains under control. Without enough precious metals to mint new coins, paper was the obvious alternative; as long as the paper currency was sufficiently hard to counterfeit, the money supply could remain under government control. And whenever the economy was weak and credit was expensive, meaning that interest rates were high or loans were simply not available, creating money was a tempting alternative.

Benjamin Franklin, a printer by trade, argued for the creation of paper money in 1720s Pennsylvania.18 The beginning of independent American thinking about money—a series of controversies that is now almost three centuries old—might be traced back to his 1729 essay, “A Modest Enquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper-Currency,” written when he was in his early twenties. Franklin argued that it was economic output that mattered, not the supply of precious metals: “The riches of a country are to be valued by the quantity of labor its inhabitants are able to purchase, and not by the quantity of gold and silver they possess.”19 For his efforts, he won a contract to print 40,000 paper pounds, for which he was paid £100, a considerable sum at the time. And that particular issuance of paper money, by increasing the supply of credit, seems to have helped the Pennsylvania economy.20

In 1751, however, the British Parliament imposed restrictions on paper currency, prohibiting “any further issue of legal-tender bills of credit by the New England colonies,” a restriction that was extended throughout the North American colonies in 1764. Colonial governments were allowed to issue interest-bearing debt (bonds) but not paper that could be used to make payments—legal tender, that is. These restrictions were seen as an imposition on the prerogatives of the colonies and became a bone of contention in the run‑up to the American Revolution.21 It was perhaps fitting, therefore, that the Continental Congress chose to finance the American Revolutionary War with paper money. In June 1775, shortly after fighting began, Congress ordered the mobilization of the Continental Army and also authorized the issuance of $2 million in “continental bills of credit.” Without the power to tax, which was reserved to the states as the true source of sovereign authority, the central government had no other way to pay for the army. Congress also had to rely on the states to authorize its bills as legal tender and to accept them as tax payments.22

The distinction between government-issued debt and government-issued currency is easy to state in theory but often confusing in practice, especially in times of political turbulence. Debt pays interest and generally has a maturity date at which the face value must be paid off in full.23 Currency, on the other hand, does not pay interest. Government debt, unlike government-issued currency, is not legal tender (although people are free to accept government bonds as payment if they choose). The Revolutionary-era bills of credit were currency, despite their name and despite the fact that they were supposed to be redeemed over time, because the states generally passed laws making them legal tender or its equivalent. But, like government debt, their value depended on people’s beliefs about the government’s solvency: as Congress’s fiscal troubles deepened and it printed more and more bills of credit, their value declined (relative to silver and gold coins, collectively known as “specie”) and then began to plummet. As the cumulative issuance of bills rose from $2 million to over $200 million, they became worth less and less. The exchange rate between paper dollars and the “Spanish milled dollar” (a silver coin) rose from 1.75 to 1 in March 1778 to 40 to 1 in March 1780, 100 to 1 in January 1781, and over 500 to 1 by May of that year.24

For all its adverse side effects, printed money played a major role in funding the Revolution. Government accounts from that period are not well ordered, but of the roughly $66 million in revenue that the national government received from 1775 to 1783, over half came from printing money.25 As mentioned in chapter 1, like many politicians over the ages, Benjamin Franklin was initially taken with the positive effects of printing money for a good cause: “This currency as we manage it is a wonderful machine. It performs its office when we issue it; it pays and clothes troops, and provides victuals and ammunition; and when we are obliged to issue a quantity excessive, it pays itself off by depreciation.”26 As Franklin realized, this depreciation, or inflation, was effectively a tax on everyone who held paper currency. But this tax soon got out of control. As Philadelphia businessman and writer Pelatiah Webster argued in a contemporary study of Revolutionary finances,

Paper money polluted the equity of our laws, turned them into engines of oppression, corrupted the justice of our public administration, destroyed the fortunes of thousands who had confidence in it, enervated the trade, husbandry, and manufactures of our country, and went far to destroy the morality of our people.27

By the time of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, most politicians understood the disruptive consequences of financing the government by printing too much money.

The birth of the United States was paid for by both a debauched paper currency and large debts that it soon defaulted on. When Alexander Hamilton became treasury secretary in 1789, his job was not just restoring the country’s credit by restructuring the debt and imposing new taxes; he also had to clean up the mess that was money in the early United States.

Hamilton proposed to base the monetary system on both gold and silver. Gold had advantages including greater stability, he argued, but it would be disruptive to withdraw the large amounts of silver that were already in use.28 He proposed “ten dollar and one dollar gold pieces, one dollar and ten cent silver pieces, and one cent and one-half cent copper pieces,” and the Mint Act of 1792 largely followed his recommendations. As gold and silver were both widely recognized bases for money at the time, this was relatively uncontroversial.29 This “bimetallic” standard meant that the dollar was defined as either a specific amount of silver or a specific amount of gold. In 1834, Congress set the ratio between the two at 16 to 1, although the market value of gold was slightly lower than 16 times the market value of silver; the California gold rush of the 1840s reduced the relative price of gold further, which meant that the United States was effectively on the gold standard.30

Basing the U.S. currency on gold and silver, however, did not mean that what we would now call the money supply was limited to precious metal coins. Currency has always coexisted with various forms of credit—which make it possible to conduct transactions without any currency at all—and a modern financial system makes possible the systematic creation of credit on a large scale. The United States was an early leader in private commercial banking, in part out of necessity.31 Commerce was essential to the country’s economic development, and shipping goods across such a large territory or even overseas required financing: sellers wanted to be paid quickly, while buyers did not want to pay for goods and then wait months before taking delivery. Bills of exchange (a form of commercial credit) were an early answer to this problem, followed by the development of a modern banking system.

Banks solve the problem by creating money. A bank takes in some of its money—whether capital contributed by the bank’s owners, deposits, or loans—in the form of government-issued currency (minted gold or silver coins then, printed bills now). When a bank makes a loan, it could give the borrower some of that currency, in which case no money is created. But, more often, the bank creates an account for the borrower and credits that account with the amount of the loan. If you take out a $10,000 home equity loan from your bank today, the bank now has a piece of paper with your signature promising to pay it $10,000 (a bank asset, since it can be sold to someone else for cash); at the same time, your checking account goes up by $10,000 (a bank liability, since you could go in and demand $10,000 in bills). That new money in your checking account was just created by the bank in the very process of extending credit. In the early nineteenth century, the bank might instead have given you “bank notes”—paper, printed for the bank, that was convertible on demand into specie.32 People were willing to accept bank notes for the same reason people are willing to accept credits to their checking accounts today: they were easier to use in transactions than large amounts of heavy gold and silver coins, and they were widely (though not universally) accepted.33 In normal times, many people were happy to hold claims on specie, rather than specie itself, so bank notes could serve as a form of money (as could bank deposits).34

Although bank notes were convertible to specie on demand, banks did not generally keep enough coins in their vaults to redeem all their notes at the same time. In 1832, for example, the Second Bank of the United States held only $7.0 million in specie, but $21.4 million of its notes were in circulation, while depositors had another $22.8 million in their accounts;35 most other banks operated along similar lines.36 In effect, even though the currency of the United States was firmly based on gold and silver, the money supply depended on the amount of risk that private commercial banks wanted to take.37 This meant, however, that banks were susceptible to financial panics, especially in the lightly regulated environment of early-nineteenth-century America. When depositors or note holders worry about a bank’s ability to pay them in hard money, they race to the teller’s window to get their money out before anyone else, which can cause even a healthy bank to collapse.38 Various schemes at the state level attempted to constrain risk taking by individual banks,39 but bank failures were common in early America, with major panics in 1819, 1837, 1857, 1860, and 1861.40 One response to a panic was for banks to simply suspend the convertibility of their bank notes into specie, which occurred in both the War of 1812 (after the burning of Washington) and the Civil War.41 In other words, bank notes were convertible into gold and silver—until they were not.

Some people have long argued that it is government intervention that causes excessive risk taking and financial crises.42 The panics of the nineteenth century, however, seemed to lend support to the opposite view—that the government could reduce volatility by increasing its involvement in the financial system. Bank runs were not limited to a system based on private bank notes; even after the standardization of bank notes during the Civil War, banking crises reappeared in 1873, 1884, 1890, 1893, and 1907.43 In 1873, British journalist Walter Bagehot argued that a “lender of last resort” was needed to backstop the financial system in a crisis; otherwise even solvent banks would be vulnerable to damaging runs.44 In the United States, the Panic of 1907 led directly to the creation in 1913 of the Federal Reserve System, the nation’s first modern central bank. The Federal Reserve had (and still has) the mandate to protect the financial system by lending money to banks in a crisis; over time, it has also gained increasing power over monetary policy.45

For centuries, banks have played a central role in the public finance systems of many countries, including the United States. Although their primary role is to pool the savings of many depositors and lend it out to the private sector (businesses and households), banks also have to have safe assets that they can sell quickly when they need cash. Government bonds can serve this purpose admirably—if the government has good credit and there is a large, liquid market for its debt. Banks can invest their excess cash (specie, in the old days) in government bonds, secure in the knowledge that they can sell them quickly at a reasonable price should the need arise; they even earn interest in the meantime. In this case, the bank is pooling individual deposits and lending them to the government, making it easier for the government to borrow money. In the United States, Alexander Hamilton made this possible by restructuring the country’s debt and restoring its credit rating, as discussed in the previous chapter, making Treasury bonds a safe asset. He also helped the process along by requiring that investors in the Bank of the United States pay for some of their shares with government bonds.46

The federal government relied heavily on private commercial banks to underwrite and distribute loans to the Treasury Department at the beginning of the Civil War.47 As the war evolved, however, the idea of using banks as a tool to help finance national borrowing took another major step forward. At the time, about 7,000 types of bank notes issued by about 1,500 banks were in circulation (along with more than 5,000 types of counterfeits), hampering commerce and creating volatility in the money supply.48 To meet its financing needs, the federal government also issued legal tender notes (“greenbacks”) that were initially convertible into Treasury bonds but later not convertible into anything.49 Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase used this chaos as an argument for a new banking system in which national banks (chartered by the federal government, not the states) would distribute “treasury notes”—a new, uniform banking currency.50 The new notes would be backed by government bonds, not by gold or silver coin directly; this meant that national banks would have to buy those bonds (at least $250 million worth, in Chase’s estimate) in order to issue the new currency. Thanks in part to patriotic sentiments inspired by the war, Chase’s plan was enacted in the National Currency Act of 1863 and the National Bank Act of 1864. Effectively forcing banks to buy and hold government bonds helped finance the Civil War and tied the banks closely to the federal government. Finally, in 1865, Congress imposed a tax on bank notes issued by state banks, driving the notes (but not the banks) out of existence.51

It was only in 1879, when greenbacks became convertible into specie, that the country went back onto the gold standard, following the examples of the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and many other countries.52 In effect, the value of the dollar was fixed at a specific amount of gold. But because the value of most things rises and falls with demand and supply, the real value of the dollar fluctuated depending on economic growth (which increases demand for money) and discoveries of gold (which increase the supply of money). When the world economy grew faster than gold discoveries, gold became more valuable relative to other goods; because the dollar was tied to gold, overall prices fell.53 Falling prices in the late nineteenth century made it harder for people—particularly farmers with mortgages—to pay off their debts (since the amount of the debt was fixed in nominal terms).54 But the gold standard and the lack of a central bank meant that there was no way to increase the money supply to prevent deflation. Proponents of “free silver,” led by William Jennings Bryan, argued that restoring silver to equal status with gold would expand the money supply, causing inflation and making debts easier to pay back.55 But Bryan lost the crucial 1896 presidential election to William McKinley, who favored “sound money,” and in 1900 the Gold Standard Act reaffirmed the gold-only standard. (By then, the discovery of new goldfields in the American West, Australia, and South Africa was causing the value of gold to fall relative to other goods, so overall prices started rising.)56

As international trade increased in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the gold standard also became the backbone of the international monetary system.57 Since each major country fixed the value of its currency relative to gold, their exchange rates were fixed relative to each other as well. If a country’s imports exceeded its exports, its currency would accumulate in the hands of its trading partners, who could then redeem it for gold—draining the national treasury of gold. Losing gold would reduce the money supply, lowering domestic prices and wages; this would reduce imports and increase exports until the trade deficit was eliminated, stopping the gold outflow. The international gold standard was suspended during World War I, but restoring it was a top priority of politicians after 1918, particularly in the United States and the United Kingdom, and most major countries were back on the gold standard by 1928.58

Then, in October 1929, U.S. stock markets collapsed, quickly followed by markets around the world. A credit bubble that had inflated in the 1920s imploded rapidly, leaving households and businesses scrambling to pay off their debts. Families with less money reduced their consumption, slowing down economic activity; debtors were forced to sell assets to raise money, causing prices to fall further; as assets lost value, they became worth less as collateral, reducing overall lending; and falling prices forced more borrowers into default on loans that remained fixed in nominal terms. Banks that had made too many risky loans began to fail, causing the money supply to contract further. A spreading panic prompted numerous bank runs, further weakening the financial system. This malfunctioning U.S. banking system acted as a negative “financial accelerator,” crippling the real economy, which slid into the Great Depression.59

The Federal Reserve, then less than two decades old, did relatively little to stop the bleeding. The gold standard limited its ability to expand the money supply and increase the flow of credit in the economy. More importantly, under the prevailing orthodoxy of the time, monetary policy was driven by the need to protect gold reserves. The textbook way to increase gold inflows was to tighten the money supply, lowering prices and wages—which only made the economy weaker. President Herbert Hoover had near-religious faith in the gold standard, and Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon saw no need to deviate from past practice: “Conditions today are neither so critical nor so unprecedented as to justify a lack of faith in our capacity to deal with them in our accustomed way.”60 Initially, as the American economy contracted, gold flowed from other countries to the United States; in order to stop these gold outflows, central banks around the world raised interest rates, effectively importing the economic slowdown to their own countries. Monetary tightening that began in Germany and the United States in 1928–1929 spread around the world as countries engaged in competitive deflation, creating a vicious cycle.61 Central banks raced to convert their holdings of foreign currency into gold, reducing the global money supply.62 High demand for gold increased its price relative to other goods; since the price of gold (in dollars) was fixed, this meant the price of everything else (in dollars) had to fall, making deflation even worse.

In 1931, unable to stop gold from draining out of its reserves, the United Kingdom abandoned the gold standard. In the United States, by contrast, Hoover and Mellon clung to the gold standard and the Federal Reserve even raised interest rates in the midst of the Depression.63 Franklin D. Roosevelt avoided making a commitment one way or the other before taking office in 1933, but many investors expected the United States to devalue the dollar against gold. Since they expected dollars to fall in value, they exchanged them for gold and other currencies—reducing American gold reserves. At the time, George Harrison, president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, said that this loss of gold “represents in itself a distrust of the currency and is inspired by talk of the devaluation of the dollar.”64

When President Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933, the United States was in the grip of a nationwide financial panic. With banks facing huge demands for cash from their depositors, most states had already declared bank holidays or severely restricted withdrawals, and the financial system was barely working.65 Roosevelt immediately declared a bank holiday beginning on March 6 and also ordered banks not to export gold—an order that remained in force after the bank holiday was lifted a week later. He quickly pushed through the Emergency Banking Act, which allowed the Treasury Department to demand that all gold in private hands (coin, bullion, or certificates) be exchanged for a nongold form of currency—a power he exercised on April 5, effectively suspending convertibility.66 Although Roosevelt expressed support for maintaining the gold standard, pressure from Congress for a weaker dollar coalesced around the Agricultural Adjustment Act, with many representatives from farm states hoping to increase inflation by expanding the money supply.67 Roosevelt decided he would have to accommodate their demands and accepted an amendment, proposed by Senator Elmer Thomas of Oklahoma, that offered various tools to weaken the dollar, including restoring silver as a base for money and changing the gold value of the dollar.68

As fears of devaluation increased, the value of the dollar began to fall relative to foreign currencies and Roosevelt expanded the prohibition on gold exports.69 At the time, many contracts—including those governing some Treasury bonds—contained gold indexation clauses, which specified that the lender could demand repayment in gold as a form of protection against inflation. On June 5, Congress abrogated all such clauses, eliminating the ability of creditors to demand gold instead of dollars.70 This was arguably an act of default, since the United States broke an explicit promise to its creditors—the only default since Hamilton restructured the debt in 1790.71 It was not until January 1934 that Roosevelt officially reset the value of the dollar against gold at $35 per ounce—down from $20.67 per ounce, where it had been since 1834.72

Some of Roosevelt’s advisers were worried; budget director Lewis Douglas famously remarked, “This is the end of western civilization.”73 But going off gold and abrogating gold indexation clauses did not destroy the government’s credit. The market reaction was almost nonexistent: long-term corporate and municipal bond yields fell from April through August 1933, and government bond yields were lower on average in 1933 than in 1932.74 The convertibility of paper into metal had been suspended often enough under the gold standard that it was not in itself grounds for panic. Most importantly, going off the gold standard and devaluing the dollar almost certainly helped the American economy overcome deflationary pressures and begin to recover from the depths of the Great Depression.75

The gold standard had been suspended before without losing its credibility. This time, however, it was blamed for exacerbating the worst economic crisis of the industrial age. While political leaders after World War I had assumed that the gold standard should be restored, there was no such consensus around how to rebuild the international monetary system after World War II. This was the question before the delegates who gathered for the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, held in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in July 1944.

The primary goals of White, Morgenthau, and almost everyone else at Bretton Woods were to rebuild war-torn Europe and prevent another Great Depression. The central question they faced was what kind of money the world would use for international transactions.

White’s proposal was to allow both gold and dollars to be used as reserves—the assets that provide backing for a country’s money. One problem with gold was that there wasn’t enough of it to support an increasing volume of international transactions; another was that a large proportion of gold production was in the Soviet Union (as well as South Africa), and the Western Allies did not want the international monetary system to be subverted by a communist country. The solution was to use dollars as a global reserve currency, since dollars could be created by the Federal Reserve in response to increasing demand. Countries could accumulate and hold dollars as the basis for their money supply rather than competing with each other for scarce gold reserves. Instead of fixing its currency against gold, each country would (roughly) fix its currency against the dollar, facilitating global trade. The United States was also willing to allow other central banks (but not ordinary people) to convert dollars into gold at the rate of $35 per ounce—something no other country was able to do. This provided a measure of stability to the entire system: if the Federal Reserve were to create huge amounts of dollars, other countries could demand to exchange those dollars for gold, draining U.S. gold reserves.

British economist and conference representative John Maynard Keynes, however, had a competing vision. As early as 1941 he had proposed an “international clearing union” for the postwar world;76 at the conference he argued for, among other things, the creation of an international currency for central banks, known as “bancor,” which would be managed by a new international organization. Keynes wanted nothing to do with gold, which he famously called a “barbarous relic,” but he also did not want the dollar to be the predominant reserve currency—in part because he was wary of American preeminence in the international monetary system.77

Keynes and the British, however, had to give way to White and the Americans on most points. No international monetary system could succeed without the support of the United States, which had the largest gold reserves and the dollars that other countries would need to import American goods. At the time, the United Kingdom was a large net debtor to other countries, which were likely to sell their pounds in the postwar world.78 The United States was unwilling to allow an international organization to control an international currency that could be used to buy American goods, and so bancor had little chance of adoption. A monetary system based on the dollar, by contrast, was consistent with American economic interests but also acceptable to other countries. They were reassured by the dollar’s convertibility into gold, which in principle gave them a way to switch out of dollars should the United States begin to abuse its control over the global reserve currency.

The Bretton Woods system provided the economic dimension of American hegemony in the postwar Western world. In many respects, it was a resounding success. Fixing exchange rates in dollar terms discouraged countries from engaging in trade wars by devaluing their currencies, promoting stability and facilitating a rapid expansion in international trade. Foreign lending and investment by Americans meant that there was a continual flow of dollars overseas. This helped other countries buy American exports, lubricated international trade (which required dollars), and enabled foreign central banks to accumulate the dollars they needed as reserves.79 In effect, the United States was operating like a bank to the world under the gold standard, holding gold and issuing the dollars that every country needed to grease the wheels of international commerce. Foreigners were willing to accept and hold dollars because they were widely accepted in international trade, which increased the global money supply.80 Countries like West Germany and Japan began increasing exports, enabling them to relax import restrictions, which helped spread economic growth to other countries.81 Western Europe in particular enjoyed growth that seemed miraculous at the time: from 1948 to 1962, GDP per person grew at 6.8 percent per year in West Germany, 5.6 percent in Italy, 3.4 percent in France, and 2.4 percent in the United Kingdom, compared to 1.6 percent in the United States.82

Like all aspects of American hegemony, Bretton Woods had its critics. French finance minister (and future president) Valéry Giscard d’Estaing complained about the United States’ “exorbitant privilege”—the ability to buy anything it wished with its own currency, since dollars were accepted everywhere.83 The fact that central banks liked to hold dollars and dollar-denominated assets, such as Treasury bonds, gave the United States the opportunity to finance its deficits by selling debt to foreigners. But at least through the 1950s, the government resisted this temptation.

The massive changes brought on by World War II extended to postwar American fiscal policy. The war, like previous conflicts, brought on huge deficits (over 30 percent of GDP in 1943) and raised the national debt to unprecedented heights (over 108 percent of GDP in 1946).84 After past wars, the usual pattern had been rapid demilitarization and consistent budget surpluses to pay down the debt. This time, however, the breakdown of the international order after World War I, coupled with the United States’ new importance in the world, made isolationism much less appealing. On March 1, 1945, President Roosevelt said to a joint session of Congress, “Twenty-five years ago, American fighting men looked to the statesmen of the world to finish the work of peace for which they fought and suffered. We failed—we failed them then. We cannot fail them again, and expect the world to survive again.”85 America’s new role in the world was soon evident in both the 1947 Truman Doctrine—“the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures”86—and the Marshall Plan, an aid program to promote European reconstruction, named after Secretary of State George Marshall. European countries desperately needed dollars to import goods from the United States and other countries, and the Marshall Plan aimed to fill that gap with up to $17 billion in loans and grants over four years.87

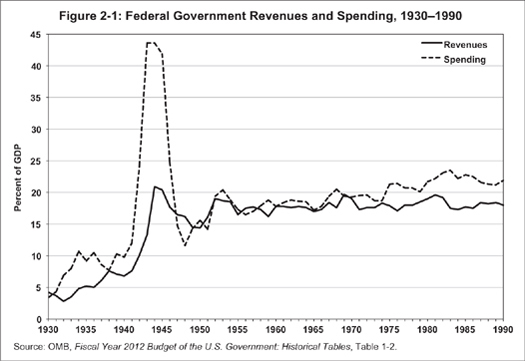

If economic aid was expensive, military spending was more expensive still. Although defense spending fell from $83 billion in 1945 to $9 billion in 1948, it immediately began growing again because of the onset of the Cold War, symbolized for Americans by the Berlin Airlift of 1948–1949. Military expenses surged after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, reaching $53 billion by 1953, consuming more than two-thirds of total government spending; even after the war ended, defense spending, largely on continued weapons building, continued to account for more than half of the federal budget through the 1950s.88 But political leaders were willing to pay for the Cold War with taxes rather than with large-scale borrowing, perhaps because, unlike a conventional war, it had no end in sight. Major tax cuts in 1945 and 1948 brought taxes down from wartime levels, but they were soon followed by tax increases, with the top marginal income tax rate rising back up to 91 percent in 1951.89 Republican president Dwight Eisenhower resisted calls from members of his own party for tax cuts, insisting on the importance of fiscal responsibility; in 1959, he refused to cut taxes to help his vice president, Richard Nixon, win the 1960 presidential election.90 As a result, the federal budget stayed more or less in balance through the 1950s (see Figure 2-1).

Figure 2-1: Federal Government Revenues and Spending, 1930–1990

Both the international monetary system and American fiscal policy, however, like so many other things, began to change in the 1960s. For one thing, the Bretton Woods system could not last forever, at least not the way it operated through the 1950s. By 1960, foreigners’ holdings of dollars exceeded U.S. gold reserves: the United States was like a nineteenth-century bank that had issued more notes than it had gold coins in the vault—and there was no lender of last resort standing behind the United States.91 In the presidential election that year, both Vice President Nixon and Senator John F. Kennedy took pains to emphasize the importance of maintaining gold reserves and fighting the so-called gold drain.92 Gold reserves were seen as a crucial element of national strength. As president, Kennedy later said,

What really matters is the strength of the currency. It is this, not the force de frappe [nuclear arsenal], which makes France a factor. Britain has nuclear weapons, but the pound is weak, so everyone pushes it around. Why are people so nice to Spain today? Not because Spain has nuclear weapons but because of all those lovely gold reserves.93

At the time, the gold drain was a constraint on monetary and fiscal policy, part of the case for lower budget deficits to maintain confidence in the dollar. Big budget deficits, it was feared, would increase aggregate demand, raising imports and sending more dollars overseas, which would eventually increase gold outflows.

But politicians have to balance many priorities, and President Kennedy was no exception. If gold reserves were important, the Cold War was more important, and Kennedy—who had been elected on a promise to close the “missile gap” with the Soviet Union—chose to increase military spending.94 Sustaining economic growth was also a top priority, and Kennedy’s administration was the first to wholeheartedly embrace deficit spending as a tool for managing the economy. In the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes first made the case for stimulating a slow economy by increasing government spending or cutting taxes, either of which would put money in people’s hands, increasing overall demand and boosting economic activity. Although many of President Roosevelt’s policies had this effect, he never fully subscribed to the theory. Kennedy’s advisers, however, were confident that Keynesian demand management could be used to fine-tune the economy by increasing deficits during slowdowns and reducing them during booms. In 1962, Kennedy began campaigning for a major, deficit-increasing tax cut as a way to increase demand and economic growth, which was eventually enacted in the Revenue Act of 1964. For the first time in American history, a president was arguing that deficits could be a good thing, not an unfortunately necessary response to a military or economic emergency.95

Kennedy’s vice president and successor, Lyndon Johnson, also found that some things were more important than a balanced budget: faced with the choice between guns and butter, he chose both. Johnson oversaw America’s increasingly expensive commitment to the Vietnam War while also expanding domestic social programs to fight poverty. In addition to higher spending on education, infrastructure, and cultural programs, Congress in 1965 created both Medicare and Medicaid, committing the federal government to buy health care for the elderly and the poor. “No longer will older Americans be denied the healing miracle of modern medicine,” Johnson declared. “No longer will illness crush and destroy the savings that they have so carefully put away over a lifetime so that they might enjoy dignity in their latter years.”96 At the time, some members of his own party were skeptical about the cost of Medicare. “I’ll take care of [the money],” the president responded. “400 million’s not going to separate us friends when it’s for health.”97

There was another reason why it was difficult for the United States to slow down the gold drain: the inflation that contributed to gold outflows was also good for the government’s balance sheet. Prices have generally risen since 1945—perhaps in part because of the prevailing view among economists that inflation is better than deflation,98 but mostly because the Bretton Woods system gave central banks more flexibility to manage the money supply. After World War II, the U.S. government was a major debtor and, like any debtor, it benefited from inflation. The government paid down the national debt, which fell from over 108 percent of GDP in 1946 to less than 24 percent in 1974 (see Figure 2-2), much faster than it had after the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, or World War I.99

One way to pay down the debt is for the government to run surpluses in its primary budget (not counting interest payments), but those surpluses after World War II were no bigger than after earlier wars. The big difference from previous historical periods was that effective interest rates on the debt were much lower than the growth rate of the economy.100 Modest but persistent inflation combined with regulation of interest rates meant that real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates were always low and often negative; since creditors’ interest payments did not keep up with inflation, part of the debt was inflated away.101 Low interest rates and rapid economic growth combined to make the debt fall rapidly as a share of the economy. Raising interest rates to slow down the gold drain, by contrast, would probably have increased the government’s own interest payments, making the debt harder to pay off.102

So while politicians paid lip service to the importance of the nation’s gold reserves, the United States continued to send dollars overseas, increasing the ratio of foreign dollar holdings to gold reserves.103 This produced the “Triffin dilemma,” named after economist Robert Triffin: outflows of dollars from the United States were a crucial part of the international monetary system, but those dollars represented liabilities of the U.S. government, which made other countries increasingly nervous about their value.104 Spending on the Vietnam War helped produce budget deficits throughout most of the late 1960s and also contributed to inflationary pressures, both of which reduced foreign central banks’ appetite for dollars. Those banks began to worry about whether they would always be able to cash in $35 for an ounce of gold, prompting a wave of gold purchasing in March 1968.105 Negotiations to reset exchange rates, which would have slowed the outflow of dollars, had little impact.106 The United States could have protected its gold reserves, but only at the cost of hurting the economy—a price its leaders did not want to pay.107

The breaking point came on August 11, 1971, in the face of countries’ requests to convert their dollar reserves into gold.108 In effect, the United States was the banker to the world, and it faced a bank run. Treasury Secretary John Connally proposed to close the gold window, refusing to convert dollars into gold and abandoning the cornerstone of the Bretton Woods system. Arthur Burns, chairman of the Federal Reserve, was opposed; at the critical secret meeting at Camp David, he argued, “The risk is if you do it now, you will get the blame for the . . . devaluation of the dollar. I could write the editorial in Pravda: ‘The Disintegration of Capitalism.’ Never mind if it’s right or wrong—consider how it will be exploited by the politicians.”109 But on August 15, 1971, President Nixon formally closed the gold window, arguing that “the American dollar must never again be a hostage in the hands of international speculators.”110 Framing the announcement as a New Economic Policy, Nixon added some tax cuts, a reduction in the number of federal employees, a ninety-day wage and price freeze, and a temporary 10 percent surcharge on imports. The era of gold was finally over.

Removing the last link to gold meant putting more power in the hands of central bankers—who are only human, after all. In the words of financial commentator James Grant, “Gold is a hedge against the human animal and an anchor to windward against human history, the tides of which sometimes bear along war, disease, revolution, confiscation and monetary bungling, as well as peace, progress and plenty.”111 Now the anchor was gone.

After Nixon closed the gold window, the dollar was devalued against other currencies, but the new exchange rates could not be maintained against another run on the dollar in 1973. The world abandoned the fixed exchange rate system for a floating rate system in which the value of a currency is set by supply and demand, and the dollar depreciated further, leading Time magazine to quip, “Once upon a very recent time, only a banana republic would devalue its money twice within 14 months.”112 But countries still needed reserves, in part to intervene in foreign currency markets, and there was no discernible shift away from the dollar as a reserve currency. In 1977 it still accounted for around 80 percent of total identified foreign exchange reserves,113 and “dollars held abroad in official reserves” increased by $91.3 billion from 1975 through 1981.114

The 1970s were a rocky time for the United States, particularly as inflation increased and the dollar weakened. But predictions that the end of Bretton Woods would mean runaway inflation were not borne out. After becoming chair of the Federal Reserve in 1979, Paul Volcker tightened monetary policy and, at the cost of higher unemployment, managed to squeeze inflation down. The next major test for the United States in the post–Bretton Woods era came in the 1980s. In 1980, Ronald Reagan won the presidential election promising to cut taxes, strengthen national defense, and balance the budget by slashing other government spending.115 His first major initiative was the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981, which cut income tax rates across the board, with the top rate falling from 70 percent to 50 percent. The largest tax cut in history combined with a severe recession in 1981–1982 to reduce government revenues from 19.6 percent of GDP in 1981 to only 17.3 percent in 1984.116 At the same time, government spending climbed thanks to increases in defense spending, producing what were then the largest peacetime deficits in history—4.8 percent of GDP or higher from 1983 through 1986.117 Large government deficits combined with large and growing current account deficitsa made the United States—both the federal government and the private sector—increasingly reliant on borrowing from other countries.118

Under the Bretton Woods system, this would have been a serious problem. Borrowing from overseas depended on foreign investors’ willingness to hold dollars (or dollar-based assets), which required confidence in the value of the dollar; but the more dollars those investors accumulated, the less faith they had that the United States would be able to maintain the gold standard at $35 per ounce, until finally the entire system collapsed. After Bretton Woods, however, every country still needed foreign currency reserves to facilitate international trade and the dollar was still the reserve currency of choice. The large budget deficits of the 1980s helped push up interest rates in the United States, making the dollar more attractive to international investors,119 and convertibility into gold was no longer an issue to worry about.

At the time, smart observers wondered how long large budget deficits and current account deficits could be sustained. In 1985, Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker warned,

Economic analysis and common sense coincide in telling us that the budgetary and trade deficits of the magnitude we are running at a time of growing prosperity are simply unsustainable indefinitely. They imply a dependence on growing foreign borrowing by the United States that, left unchecked, would sooner or later undermine the confidence in our economy essential to a strong currency and prospects for lower interest rates.120

But for the time being, at least, the end of Bretton Woods meant that foreigners were willing to hold more dollars, not fewer dollars, since confidence in the dollar was no longer constrained by physical gold reserves. Heated rhetoric about deficits became a constant theme in Washington, producing (among other things) the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act of 1985, which attempted to mandate balanced budgets. (It was a failure, because Congress and the president could modify its deficit targets, use accounting gimmicks to meet them, or simply repeal its enforcement provisions if need be.121) But in the post–Bretton Woods world of the 1980s, the United States largely escaped any severe consequences of both its budget and current account deficits. In 1990 and 1993, Presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton pushed through budgetary legislation that cut spending and increased taxes. As budget deficits fell through the decade and America gained a reputation for stable growth and low inflation, the dollar only became more attractive as a safe store of value.

The new world, however, contained greater risks for many other countries. Increasing financial liberalization—meaning that money could move in and out of countries more easily—heightened the volatility of the international economy. In the 1990s, foreign capital rushed into the newly industrializing countries of East and Southeast Asia, fueling economic booms that caused rapid increases in asset prices and currency values. Cheap money encouraged companies to borrow heavily to invest in risky projects, until the boom could only be sustained through continual infusions of new capital. Then, in 1997, currency traders began betting against the Thai baht, forcing the government to buy baht to defend its value—which required foreign currency reserves. When the government could no longer support the baht, the currency promptly collapsed, taking the overleveraged economy with it (because domestic companies could no longer repay money they had borrowed in other currencies), and foreign capital rushed out even faster than it had rushed in. The “Asian financial crisis” went on to wreak havoc with the economies of Indonesia, South Korea, and other countries, including even Russia. The globalized economy meant that financial panics could spread around the world rapidly as investors herded out of the same countries they had herded into only a few years before.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), a product of the Bretton Woods conference, extended emergency loans to several countries during the Asian financial crisis, but the money came with numerous conditions that made the IMF deeply unpopular in certain parts of the world, reinforcing a stigma associated with borrowing from the IMF that had been developing for decades. The lesson, for many emerging market countries, was that they never wanted to have to borrow from the IMF again.122 Attempts to ensure that the private sector does not borrow too much foreign capital, however, have had limited effectiveness.123 So central banks around the world have decided to protect themselves by building up large war chests of foreign currency reserves (which they can use to support their currencies and pay foreign debts in a crisis)—particularly U.S. dollars. Some countries—most notably China—also accumulate dollars as a way of suppressing the value of their own currencies.124 China’s huge trade surplus with the United States gives it a surplus of dollars, but if it traded them for yuan on the open market, that would increase the value of the yuan, making it harder to export goods; so instead it invests those dollars in Treasury bonds, bonds of U.S. government agencies, and other dollar-denominated assets. In summary, the instability of the global economy increases demand for safe assets, and there is still nothing safer than U.S. Treasury bonds.

In 1948, after the Bretton Woods system was established, all the international reserves of all the central banks in the world came to $49.5 billion, of which $34.5 billion was gold and $13.4 billion was “foreign exchange,” largely dollars. In 1968, after twenty years of global growth, total international reserves had only increased to $73.5 billion, of which $37.8 billion was gold and $29.1 billion was foreign exchange.125 At the time, if roughly $20 billion out of that $29.1 billion was held in dollars, that would have been just 2 percent of U.S. GDP—too small an amount to have any impact on the ability of the United States to finance its debts.126

In 2011, by contrast, total foreign exchange reserves reported to the IMF amounted to more than $7 trillion, and this excludes part of the considerable holdings of China, Saudi Arabia, and Abu Dhabi.127 The total foreign assets held by central banks and sovereign wealth funds (government investment funds) are probably closer to $10 trillion, of which over 60 percent is in dollars.128 Since a large proportion of these dollars are invested in Treasury securities—the classic central bank reserve asset—foreign governments have become a major source of financing for the U.S. national debt, which reached $10.1 trillion in September 2011.129 Foreigners in general, including private households and companies as well as central banks and other government agencies, own about $5 trillion of Treasury bonds.130

In today’s unstable world, this enormous international appetite for safe dollar assets has given the U.S. government the largest credit line in economic history.131 Even when a financial crisis that originated in the United States created record peacetime deficits in 2009 and 2010, surging demand for safe assets pushed interest rates on Treasury bonds to historically low levels.132 Under the Bretton Woods system, the capacity of the world to buy American bonds was limited by American gold reserves; today it is limited only by market demand, which has turned out to be much more forgiving. As long as people around the world think that the U.S. economy will continue to grow and that government policy will remain generally responsible, they are willing to buy and hold dollar assets.

Markets, however, can turn against you. The dollar’s status as the world’s effective reserve currency is not written into any treaty that has been ratified by the community of nations. Instead, it depends on the belief that the United States will not mismanage the dollar to the point where it will lose a lot of its value—and on the fact that the dollar has no serious competitor at the moment, especially with the eurozone beset by multiple sovereign debt crises. Beliefs can change, or other currencies can become more attractive, or countries like China might decide they don’t need quite so many reserves as they have now. And then the central bankers and sovereign wealth fund managers of the world might decide they don’t need as many dollars, making it harder for the U.S. government to finance its budget deficits. The fact that so many countries have been willing to buy Treasury bonds because of the need for safe reserves, rather than the pursuit of high interest rates, has benefited the United States enormously. But it also means they could abandon Treasuries for noneconomic reasons, reducing the government’s access to credit.

The end of Bretton Woods and the increase in the federal government’s borrowing capacity do not tell the whole story, however. Ever since Ronald Reagan, American politicians have relentlessly inveighed against deficits and claimed the high ground of fiscal responsibility—yet the government has run deficits almost every year, culminating in the trillion-dollar deficits of recent years. Never before has there been such a combination of balanced budget rhetoric and deep deficits. What happened?

a The current account measures the difference between money earned from the rest of the world (mainly through exports and income on investments in foreign countries) and money paid to the rest of the world (mainly through imports and foreigners’ income on investments in this country). In recent American history, the major contributor to current account deficits has been trade deficits (importing more than we export).