A billion here, a billion there, and soon you’re talking real money.

—Attributed to Senator Everett Dirksen (1896–1969)1

A specter is haunting the Western world: the specter of austerity. New governments in Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and the United Kingdom have all solemnly invoked large government deficits to justify harsh measures including both sharp tax increases and major cutbacks in public spending. Austerity has an appealing narrative resonance: after years of living beyond our means, it is now time to face facts, assume our responsibilities, and make sacrifices—or else we will go the way of the Roman Empire.

It makes a good story—but that doesn’t make it true, at least not everywhere. We take the national debt seriously (seriously enough to write hundreds of pages about it). The federal government does need to fill a hole in its long-term budget that ranges from 3.0 percent to 5.5 percent of GDP (depending on the fate of the Bush tax cuts). But we can fill that hole without gutting our major social insurance programs, without eliminating the meager safety net for the poor, and without raising taxes to the levels that prevailed from World War II until the 1970s. We can bring the national debt under control in a way that encourages economic growth, preserves the essential services and programs that many Americans depend on, and spreads the burden of lower spending or higher taxes fairly across the population. This chapter shows how.

Of course, we are not under the illusion that our proposals will magically break open the logjam of American deficit politics. The problem is not a shortage of deficit reduction plans; indeed, the past few years have seen a bumper crop of such plans, many with more illustrious sponsors.2 We do not expect all readers to agree with us on how the deficit should be reduced; even those who share our views about the historical causes of our current and future deficits will have different visions for our society and the place of the federal government. Our goal is simply to show that we can achieve a sustainable level of national debt while maintaining a government that plays the crucial role we expect from it today—protecting all of us from major risks to our welfare today and investing in a more prosperous future.

The first important question is what to do with the tax cuts that are due to expire under current law, most notably the income and estate tax reductions originally passed under President Bush in 2001 and 2003.a They are big: extending the income and estate tax cuts alone will increase the 2021 deficit by almost 3 percent of GDP and increase the 2021 national debt from 60 percent to 76 percent of GDP.3 As discussed in the previous chapter, extending them would also increase our long-term budget gap (the amount by which annual deficits must be reduced) from 3.0 percent to 5.5 percent of GDP. The tax cuts also represent a unique opportunity to reduce the deficit in our difficult political climate. Because they are already scheduled to expire under current law, Congress simply has to do nothing. Given how hard it is for Democrats and Republicans to agree on any spending cuts or tax increases, it is hard to imagine Congress enacting anything that would reduce the national debt by 16 percentage points within a decade. When it comes to expiring tax cuts, gridlock can help reduce deficits.

In addition, letting the tax cuts expire is good policy. The major provisions of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, as extended in 2010, are:

• Reductions in all income tax rates, with the highest rate falling from 39.6 percent to 35 percent;

• Reductions in tax rates on long-term capital gains, with the highest rate falling from 20 percent to 15 percent;

• Taxation of stock dividends at lower rates (rather than at ordinary income tax rates);

• Elimination of existing rules that reduced the ability of high-income taxpayers to lower their taxes through personal exemptions or itemized deductions;4

• Increases in the child and dependent care tax credits;

• Gradual repeal of the estate tax; in 2010, Congress reinstated the tax on estates over $5 million (up from $1 million in 2001).

In addition to extending the 2001 and 2003 income and estate tax cuts (through 2012), the December 2010 tax act also reduced the Social Security payroll tax by 2 percentage points (through 2011, later extended through February 2012) and extended some tax cuts introduced in the 2009 stimulus bill.

The main problem with the Bush tax cuts is that, in addition to vastly increasing government deficits, they constituted a major transfer from the federal government to the rich (relative to preexisting policy). As described in chapter 3, a large majority of the tax cuts went to the richest 20 percent of households, with the greatest benefits for the very richest families, both in dollar and percentage terms. If the federal government were simply throwing money away, this might have been defensible since most households got some tax cuts (but not households that are only subject to payroll taxes). But most federal spending is payments on behalf of individuals (Social Security checks, Medicare or Medicaid reimbursements, Pell Grants, and so on), which clearly benefit real people; the difficulty of getting Congress to agree to cut any spending demonstrates that most other spending must benefit someone. Since the biggest chunk of government spending is on insurance programs for all working Americans, tax cuts that favor the wealthy must eventually translate into lower benefits for the middle class—unless they are paid for by future tax increases aimed primarily at the wealthy. There is a reasonable argument to be made that both taxes and spending are too high and therefore both should be reduced. But that argument implies that taxes and spending should be reduced at the same time; it does not justify a permanent reduction in taxes on the rich that will be paid for through unspecified future spending cuts that must largely be borne by the poor and the middle class.5 In short, the income and estate tax cuts were bad policy a decade ago, and extending them is simply making bad policy permanent.

The Bush tax cuts had another rationale, which was that lower taxes would increase the incentives to work and to save, boosting economic growth in the long term. But there is little evidence that they had the impact claimed by their supporters. Growth following the tax cuts was lower than in the “high-tax” 1990s, even before the recession caused by the recent financial crisis.6 It is difficult or impossible to isolate the impact of the tax cuts from everything else that has happened since 2001, but there is a basic reason to be skeptical that they have helped the economy in the long term: although lower taxes can boost growth by increasing incentives, lower taxes that are paid for through larger deficits mean reduced saving, higher interest rates, and slower growth. In the words of two economists at the Brookings Institution:

Several studies have quantified the various effects noted above in different ways and used different models, yet all have come to the same conclusion: Making the tax cuts permanent is likely to reduce, not increase, national income in the long term unless the reduction in revenues is matched by an equal reduction in government consumption.7

In 2010, Congressional Budget Office analysis also indicated that extending the tax cuts would increase economic growth in the short term but decrease it in the long term (because higher government borrowing would crowd out private investment), making the economy smaller in 2020 than it would have been otherwise.8 Again, there is a valid argument that tax cuts coupled with spending reductions could be good for the economy—but that argument does not apply to extending the Bush tax cuts on their own.

The last argument against extending the income and estate tax cuts is that you shouldn’t raise taxes when the economy is weak. This is a reasonable argument. Since unemployment is still likely to be high at the end of 2012, it would be better to extend some of the tax cuts until the economy is recovering and then let them expire, perhaps even by passing a law that left them in place until the economy hit certain benchmarks. In practice, however, Republicans in Congress are highly unlikely to agree to any plan to phase out the tax cuts; and each time a tax cut is extended, the more it seems like a permanent feature of the tax code, and the harder it is to eliminate. Ideally we would let the tax cuts expire and use some of the new revenues to finance explicit, short-term stimulus measures that have more impact on employment and have little chance of becoming permanent (such as spending programs or one-time tax rebates).9 But politically speaking, this is even more unlikely. In these circumstances, where the only realistic choices are no tax cuts or permanent tax cuts, we think the right choice is no tax cuts. While this could hurt growth in the short run, it should make the economy larger over the next decade.10 More importantly, this is the single biggest step we can take toward assuring the revenues necessary to pay for Social Security, Medicare, and the other insurance programs that the middle class needs in the long term.

Unfortunately, it is highly likely that most or all of the income and estate tax cuts will be made permanent. President Obama wants to extend all of the tax cuts for households making less than $250,000—which accounts for the large majority of their dollar value.11 Republicans have long wanted to make all of the tax cuts permanent, and Grover Norquist has said that any deal that extends only some of the tax cuts would count as a tax increase and hence would violate the Taxpayer Protection Pledge.12 With unanimous agreement among the principals that most of the tax cuts should be made permanent, even the power of gridlock will probably be insufficient to prevent their extension. For this reason, the rest of this chapter assumes that all of the income and estate tax cuts will be made permanent. (If that does not happen, then our long-term deficit problem will be correspondingly smaller, and fewer of our other recommendations will be necessary.)

In addition to the major tax cuts introduced under President George W. Bush and extended under President Obama, many other tax breaks are scheduled to expire over the next decade, ranging from the “Depreciation Classification for Certain Race Horses” to the “Partial Expensing of Certain Refinery Property.” Most of these are relatively small; the largest are a bonus depreciation provision (which allows businesses to deduct the cost of their investments faster) and a tax break that helps companies shield foreign income from U.S. taxation.13 If they are all extended (in addition to the income and estate tax cuts), they will together add 0.5 percent of GDP to the 2021 deficit and increase the 2021 national debt to 80 percent of GDP.14 As a general rule, we think that all of these tax provisions should expire. A temporary tax break should exist if Congress originally thought it was only needed for a certain period of time; in that case, it should be extended only if Congress decides that its original rationale is still valid. If a tax break really is good long-term policy, it should be individually justified and made permanent, even if it needs sixty votes in the Senate. In this case, as opposed to the income tax cuts, we think it is reasonably likely that many other tax breaks will be allowed to expire; for example, the largest individual line item is the bonus depreciation provision, which has historically been justified as an economic stimulus measure and should be allowed to lapse when the economy recovers.15

Social Security is the primary source of retirement income for most Americans. Because the ratio of workers (who make payroll tax contributions) to retirees (who collect benefits) is falling, the system will run increasing deficits in the future, reaching 1.3 percent of GDP around 2030, when most of the baby boomers will have retired. The deficit will then fluctuate around that level for several decades before slowly rising due to increasing life expectancy.16 Over the next seventy-five years (the period over which Social Security’s finances are conventionally measured), the cumulative deficit—the gap between the payroll taxes we pay and the benefits we are supposed to get—is equivalent to 2.2 percent of taxable payroll (the total amount of earnings subject to the payroll tax).17

The solution long sought by conservatives and proposed by President George W. Bush is to privatize Social Security, making it essentially like a 401(k) plan, where at least some of each person’s contributions would go into her own individual account. From the budgetary perspective, the main benefit of privatization is that it eventually eliminates the government’s long-term obligations. At some point, what retirees get will depend solely on their savings decisions and investment returns, just as with a 401(k) plan. The federal government will just be an administrator, and so there cannot be a Social Security deficit.

The problem with privatization is that it dismantles Social Security as we know it today. The whole point of Social Security is to provide guaranteed income in retirement and protect people against a wide range of risks—disability, having a spouse die young, living too long, poor investment returns—by shifting those risks to the population as a whole, via the federal government. Individual accounts do not protect people against any of these risks unless they are layered over with additional features (mandatory contributions, mandatory annuities, minimum benefits, disability benefits, and so on) that turn them back into traditional Social Security. By making Social Security more like the rest of our retirement “system”—tax-advantaged accounts, such as 401(k)s, that people can use (or not) to save for retirement—privatization would most likely leave many more Americans unprepared for retirement. A much simpler solution to the long-term Social Security deficit is to acknowledge that payroll taxes won’t be enough to cover benefits in the long term and either increase the former or reduce the latter.

There are many ways that this could be done.18 We favor a combination of four policy changes: increasing the cap on earnings that are subject to the payroll tax, indexing the full benefit age to life expectancy, broadening the system to include all newly hired state and local government employees, and increasing the payroll tax rate. The payroll tax is currently 12.4 percent of earnings, but is only assessed on the first $106,800, an amount that is adjusted for inflation. When the cap was set in 1983, it covered 90 percent of all wage earnings in the country. Since then, however, the proportion of earnings that escape the payroll tax has increased from 10 percent to 16 percent, primarily because of increasing inequality.19 (Since rich people make more than $106,800, as the rich earn a larger share of total income, more income escapes taxation.) The cap should be increased so that it includes 90 percent of all wage earnings, as in 1983, and should be indexed at that level. This would reduce the program’s seventy-five-year deficit by 0.5 percent of taxable payroll.20 Maintaining a cap on taxable earnings means that the payroll tax is slightly regressive, but the program as a whole is modestly progressive today (because the progressive benefit formula outweighs the regressive payroll tax), and would be more progressive with the higher cap that we propose.21

Social Security’s normal retirement age—the age at which you can begin drawing full benefits—is sixty-six for people retiring now, but will slowly increase to sixty-seven for people born in 1960 or later. (You can begin taking benefits as early as age sixty-two, but your monthly benefits will be lower.)b Greater life expectancy, by increasing the ratio of retirees to workers, is one of the contributors to Social Security’s long-term deficits; at the same time, because it increases the amount of time that people collect benefits, it also makes Social Security more valuable to retirees. If the normal retirement age is indexed to rise as life expectancy increases (beginning with a full retirement age of sixty-seven for people born in 1960), the ratio of retirees to workers can be kept roughly stable except for fluctuations in births and immigration. Over time, the full retirement age would increase by one year about every twenty-five years; on average, that means that each person would be expected to work about one year longer than her parents.22 This change would reduce the seventy-five-year deficit by 0.6 percent of taxable payroll.23

Social Security currently does not cover more than six million employees of state and local governments that previously opted out of the system.24 These employees do not pay payroll taxes and will not receive retirement benefits (at least not for the years they spend as government employees). The system should be expanded to cover all newly hired government employees. This would give them access to a highly dependable pension system, which is particularly important given the current political and financial pressures on state pension systems. Social Security can coexist with another retirement plan (as is the case for every private sector employee who has a traditional pension or a 401(k) plan), so state and local governments could elect to preserve or scale back their existing retirement plans for new hires. Broadening Social Security coverage would improve the system’s finances because most newly hired employees would make contributions for many years before beginning to receive benefits. This change would reduce the seventy-five-year deficit by about 0.2 percent of taxable payroll.25

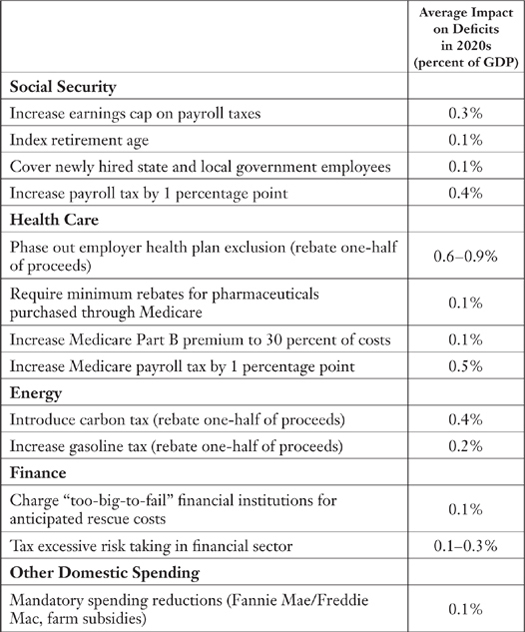

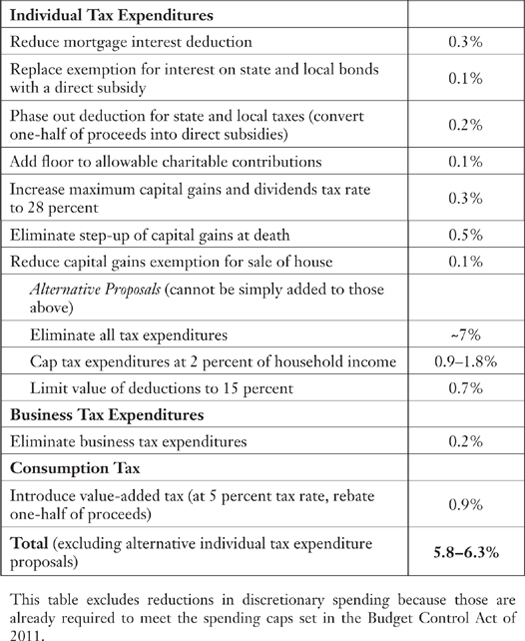

Finally, increasing the payroll tax rate by 1 percentage point, from 12.4 percent to 13.4 percent, would reduce Social Security’s seventy-five-year deficit by another 1.0 percent of taxable payroll.26 We favor increasing the tax rate (gradually, over several years) rather than reducing benefits because Social Security benefits are already quite modest, averaging around $13,000 per year.27 Given how little many households have saved for old age, this is not the time to weaken the one component of our retirement system that seems to be working reasonably well.28 Together, these four reforms would bring Social Security’s finances roughly into balance for the next seventy-five years.29 Beginning in the 2020s, they would also reduce annual federal budget deficits by about 0.9 percent of GDP.c 30 They are not a permanent solution, since they would leave the program with a modest deficit after the seventy-five-year horizon, but given all the things that can happen between now and the 2080s, we think additional tax increases or benefit reductions would be premature at this point.31

Our expensive yet mediocre health care is one of the major problems facing Americans today. Many businesses struggle with the rising costs of their employee health plans, which force them to charge higher prices to customers, clamp down on wages, drop their health benefits, or shift jobs overseas. Cutbacks in employer-sponsored health plans, combined with the high price of buying health insurance directly from insurers, have left fifty million Americans without any type of coverage.32 Even families with insurance are highly vulnerable to medical emergencies: illness or injury is a significant factor in more than half of all bankruptcies, and in more than three-quarters of these cases, the person suffering the illness or injury had health insurance at the time.33 Health care spending continues to rise, even after accounting for inflation, demographic shifts, and increasing prosperity. Because the federal government is committed to buying health care for about one hundred million people, including the elderly, the poor, veterans, and federal employees, the cost is expected to take up a larger and larger share of the federal budget, growing from 5.6 percent of GDP in 2010 to 10.3 percent in 2035.34

This spending can be reduced in two ways: reducing health care costs overall and reducing the government’s share of that spending. The former is clearly better for society as a whole, if it can be done without significantly hurting health outcomes. Otherwise, reducing the government’s obligations simply shifts costs onto businesses and households, leaving everyone no better off in the short run.35 The problem is that it is by no means clear how to hold down growth in health care costs. There is ample evidence that we could spend less without becoming any less healthy—other countries obtain comparable or better outcomes for much less money, and high-spending regions within the United States do not achieve better outcomes than low-spending regions36—but how to get there is open to debate: simply spending less could reduce valuable care as much as unnecessary care.37 A growing body of comparative effectiveness research is helping to identify which procedures are likely to help and which are not. For example, aggressive treatment of people with advanced terminal illnesses not only is expensive but also results in more people spending their last days in the intensive care unit and dying in the hospital; palliative care programs, which focus on relieving suffering and improving quality of life, can save money, increase patients’ comfort, and at least in some cases help people live longer.38 But even with this research, there is no easy way in our current, fragmented system to induce providers to stop conducting unnecessary procedures or to hold them accountable for patient outcomes.

Most other developed countries, by contrast, have universal health insurance systems, which come in several different forms. At one extreme are countries like England, where health care is provided by the National Health Service and financed by taxes (with a small private insurance sector providing supplemental insurance). Then there are countries like Canada and France, where health care services are delivered by both the public and private sectors, but universal health insurance is provided by provincial governments or government-regulated insurance funds and financed by taxes; in both cases, private insurers also offer supplemental health insurance plans. Finally there are “managed competition” systems in countries like the Netherlands and Switzerland, where everyone is required to buy health insurance from private insurers, but the insurance market is tightly regulated to ensure access to basic plans.39

A universal, government-sponsored health insurance plan is one way to control costs over the long term. If everyone is enrolled in a single basic insurance plan—which could be funded by premiums, deductibles, and copayments in addition to taxes (like Medicare today)—that plan would have the power to set payment rates for services and medications. This would make it possible to limit future spending growth without sacrificing access to care. Unlike today, when doctors and hospitals are free to turn Medicaid and Medicare patients away if those programs don’t pay them enough, a universal health plan would be the only payer for many services, ensuring that providers would accept its payment rates. (Private insurance companies could offer supplemental insurance plans providing additional benefits not included in the basic plan.)40 Varying levels of copayments could be used to guide people toward preventive care and away from procedures with questionable benefits. Universal insurance would require higher payroll taxes than we pay for Medicare today, but those higher taxes would replace the amount we currently pay in health insurance premiums. Over the long term, such a plan could reduce total health care spending—the number that really matters to our wallets—because the universal plan could control how much it pays for services.

A universal health plan would have other benefits. Over time, it could adopt payment practices that increase accountability among providers, such as bundled payments for a given episode of care (as opposed to paying for each service individually) or a system of bonuses and penalties based on quality measures. It would also separate health insurance from employment, ensuring that people do not lose their coverage when they leave their jobs—which is often when they need it most.41 Of course, nothing comes for free: if the government sets payment rates too low, hospitals will go out of business and fewer people will want to be doctors, which could reduce the overall supply of health care services.42 The experience of other countries, however, shows that it is possible to have lower costs and better outcomes with a universal, government-sponsored health plan. In any case, this would at least allow us to make conscious trade-offs between spending and outcomes through our democratic system; today, instead, virtually everyone agrees that spending is growing too fast, but we have no good way of doing anything about it.

Universal, government-sponsored health insurance is probably a political impossibility, at least today. President Obama’s health care reform plan, which relies entirely on the private insurance market, barely made it through Congress with zero Republican votes and would certainly not be passed today. This means that we will have to find other ways to slow the growth of health care spending and close the federal government’s long-term budget gap. The best way to reduce spending is probably to shift toward new health care delivery models that make providers accountable for both costs and quality; this will give them the incentive to improve coordination, apply the lessons of comparative effectiveness research, and focus on outcomes rather than simply maximizing their revenues by supplying unnecessary services.43 The Affordable Care Act of 2010 attempted to give the system a nudge in this direction, but no one knows what it will take to turn the enormous ship of U.S. health care spending in a new direction.

In this uncertain environment, we need to take additional steps to reduce the government’s health care deficit. The first place to look is the tax break for employer-sponsored health plans, which are currently excluded from the income tax and from payroll taxes—even though they are valuable compensation received by employees. Not only will the employer health plan exclusion cost the Treasury Department almost $300 billion in 2012, or 1.9 percent of GDP, but it also contributes to the problem of high health care costs.d 44 Because of the exclusion, it is cheaper for companies to pay their employees in health benefits than in wages; this means that they buy more generous health plans than they would without the tax break. This distortion increases demand for health insurance and probably increases health care spending modestly.45 It locks people into their current jobs, making it harder and riskier to switch employers and cutting them off from health coverage when they lose their jobs involuntarily. And it is poorly targeted, since rich people are more likely to have employer-sponsored health plans to begin with and the exclusion is worth more to people in high tax brackets: more than 40 percent of the tax break goes to families in the top quintile by income, and less than 2 percent to families in the bottom quintile.46

For these reasons, the employer health plan exclusion should be phased out,e as in the bipartisan Healthy Americans Act proposed by Senators Ron Wyden and Bob Bennett (but never seriously considered).47 One concern is that this would accelerate the decline of employer-sponsored health plans, which are still the way that a majority of Americans get health insurance. The Affordable Care Act, however, created a system of state-based exchanges where insurers offer plans meeting basic minimum standards; these insurance plans must be available to anyone, cannot be priced based on preexisting conditions, and cannot be taken away.48 In addition, the Affordable Care Act subsidizes insurance purchased on an exchange by low- and middle-income families.49 We also recommend spending half of the proceeds from eliminating the current tax break on cash rebates to low- and middle-income workers (delivered either through the income tax or the payroll tax system). Roughly speaking, half of the tax break currently enjoyed by high-income workers would go to reduce deficits, while the other half would be shared among all low- and middle-income workers, not just those fortunate enough to get health care from their employers. It’s difficult to estimate how much revenues would increase under this plan, but we expect it would be between 0.6 percent and 0.9 percent of GDP.50

There are other ways to lower government health care spending without reducing beneficiaries’ access to care. The most significant is equalizing the treatment of prescription drugs by Medicare and Medicaid. Today, pharmaceutical companies must pay minimum rebates to the government for drugs purchased through Medicaid; as a result, it receives significantly larger discounts than Medicare for the same drugs.51 Various other inefficiencies in these programs could be eliminated: Medicare currently overpays teaching hospitals for the incremental costs of training doctors; Medicare overpays for some types of rehabilitation and other medical care in long-term settings; and Medicaid can reduce spending on durable medical equipment by adopting Medicare’s practices. But the savings available from these types of reforms are relatively small: minimum prescription drug rebates for Medicare would save 0.1 percent of GDP, and additional cost-saving measures proposed by the Obama administration in 2011 would save another 0.1 percent.52

The last way to reduce the long-term health care deficit is to increase Medicare revenues, either from current beneficiaries, through higher premiums, deductibles, and copayments, or from future beneficiaries, through payroll taxes.53 We favor a balanced approach that does not concentrate the burden of health care inflation either on current workers or on the elderly; looked at from an alternative perspective, most of us will work for part of our lives and be old for part of our lives, but it is better to spread the burden across both periods than to impose it only in one. First, we recommend gradually increasing Medicare Part B premiums so that they cover 30 percent of the program’s costs instead of only 25 percent, as under current law. This would work out to an increase of about $240 per beneficiary per year in today’s dollars, and would increase revenues by 0.1 percent of GDP in the long term.54 This premium increase is slightly progressive: low-income beneficiaries are protected by a provision of Medicaid, while a growing number of high-income beneficiaries pay higher premiums under current law. We think this is preferable to raising revenues through higher deductibles and copayments, which will concentrate the burden on people with poor health who are already incurring greater out-of-pocket expenses for health care.

Second, we recommend raising the Medicare payroll tax, which currently funds the Hospital Insurance program (Part A).55 For most people, the payroll tax rate has remained at 2.9 percent since 1986, a period during which health care spending has grown by two-thirds as a share of the economy.56 That payroll tax is perhaps the best bargain on the planet: it buys you guaranteed hospital insurance from the day you turn sixty-five, no matter how healthy or unhealthy you are, until the day you die—at a tax rate that hasn’t changed in a quarter-century.57 We recommend gradually increasing the payroll tax by 1 percentage point, to 3.9 percent—still far less than the increase in health care costs since 1986. This means that someone making $50,000 a year would pay up to $500 more per year in taxes (depending on how the employer’s share of the tax is distributed), and total payroll tax revenues would increase by 0.5 percent of GDP.58

This is not a pretty picture, with higher payroll taxes for current workers and higher premiums for beneficiaries. The better solution is to change the way health care is delivered, so that we spend less and get better care. Medicare itself is far from a perfect system; in particular, it epitomizes the fee-for-service model (in which providers are paid by the procedure, regardless of results) that produces high costs and mediocre outcomes. We should continue to implement reforms to government health care programs that increase accountability and promote patient-centered care. But we cannot simply assume that they will solve all our problems, nor do we know how long it will take to bring costs under control. In the meantime, we need to be prepared for a world in which health care costs continue to grow faster than the rest of the economy. Our proposals are one way to pay for those higher costs without forcing people to go without needed care. The alternatives—higher cost sharing at the moment that people need services, arbitrary caps on government spending that ignore whether people get the care they need, or health insurance vouchers that are not indexed to actual costs—are all mechanisms that save the government money by forcing families to pay more out of their own pockets.

Along with Social Security and health care, the third major component of the federal budget is defense spending. We spend a lot on national defense: $689 billion in 2010, more than in any year since World War II after accounting for inflation; 4.7 percent of GDP, more than in any year since 1992, when the military was shrinking after the Cold War; 20 percent of all federal spending; and 43 percent of all military spending in the world, almost six times that of any other country.59 Even excluding current operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, real defense spending is higher than it was during the Cold War, when we had a military superpower as a mortal enemy.60 Nor is it clear that our current defense spending—which pays for over five thousand nuclear warheads and a navy that is larger than the next thirteen combined (eleven of which belong to our allies or partners), among other things—buys us the security we need today.61 Since 2001, our primary enemies have been terrorist groups that someday may gain access to nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction. Perhaps someday, when China has built multiple aircraft carrier groups, we will need the eleven we currently have (no other country has more than one carrier group). But that day is not today.

At a high level, it should be possible to gradually reduce overall defense spending to 1999–2001 levels (3.0 percent of GDP) or lower without significantly increasing our national security risks. As Lawrence Korb, an assistant defense secretary under President Reagan, has pointed out, it was essentially this relatively inexpensive military that rapidly drove both the Taliban and Saddam Hussein from power.62 The budget submitted by President Obama in 2011 already projected that defense spending would fall to around 3 percent of GDP by 2021.63 Analysts from across the political spectrum have also agreed on various specific steps that could be taken to reduce defense spending. For example, the left-leaning Center for American Progress, the bipartisan Sustainable Defense Task Force, and conservative Republican senator Tom Coburn have all endorsed several spending reductions such as decreasing the number of aircraft carrier groups, limiting procurement of the F-35 and V-22, lowering troop levels in Europe and Asia, shrinking the nuclear arsenal, and reforming the Defense Department’s health care system—steps that together would reduce spending by hundreds of billions of dollars over the next decade.64 The decade following the September 11 attacks also saw the expansion of a vast, overlapping, poorly coordinated, and expensive intelligence apparatus, with a total cost exceeding $80 billion each year (most of which is outside the military budget).65 With operations split across more than 1,200 government organizations and 1,900 private contractors, it is likely that eliminating redundant operations could both reduce spending and actually increase our security by improving communication among agencies—although organizational complexity and secrecy present high barriers to greater efficiency.66

We do not count any military or intelligence savings toward our long-term deficit reduction goals because we expect that these or similar cuts will be necessary to comply with the caps placed on discretionary spending by the Budget Control Act of 2011.f These savings opportunities, however, imply that our current high levels of defense spending can be brought down as required without materially compromising our national security.

One of the major challenges we face as a country is the need to transition away from fossil fuels and toward new energy sources. Over the long term, the price of fossil fuels is likely to increase as we exhaust more easily accessed deposits of oil, coal, and natural gas, and especially as developing countries such as China and India increase their energy consumption. At the same time, fossil fuels impose significant costs on society, including air pollution (and its harmful health effects), dependence on various undemocratic or otherwise unsavory regimes around the world, and long-term climate change. Yet our current energy “strategy”—a hodgepodge of subsidies and tax breaks for renewable energy sources, biofuels such as ethanol, and fossil fuels—is unlikely to ensure long-term energy independence or to significantly reduce emissions of harmful pollutants and greenhouse gases.

The basic problem is that the total societal costs of using fossil fuels are not reflected in their prices; because they are too cheap by this standard, we use too much. The textbook solution is to impose taxes on fossil fuels (and other sources of greenhouse gas emissions) that reflect the additional costs they impose on society. Ordinarily we think taxes introduce distortions into the economy, changing the way resources are allocated. In this case, taxes can reduce distortions, making the economy more efficient. A “carbon tax” would be assessed on each ton of carbon dioxide (or its equivalent in other greenhouse gases) from the major sources of emissions—primarily combustion of oil, natural gas, and coal for electricity generation, transportation, industrial and commercial operations, and residences.67 Properly designed, this tax could be applied to approximately 90 percent of all U.S. emissions.68 Over time, it would induce companies and households to become more efficient at producing and using energy, thus reducing emissions.

Ideally, the tax per ton of carbon dioxide should be equivalent to the total societal cost of that ton of carbon dioxide—which is notoriously hard to estimate because it depends on complex climate models, estimates of the monetary cost of climate change, and discount rates (how much we care today about bad things that will happen in the future).69 An alternative approach is to estimate the tax rate necessary to lower greenhouse gas emissions to a level that reduces the risk of major climate impacts.70 Policy analysts have suggested that the price should be around $20 per ton of carbon dioxide and should rise from there (to encourage progressive reductions in emissions).71 To put this in perspective, $20 per ton of carbon dioxide emissions works out to an additional 18 cents per gallon of gasoline—a price increase that is not insignificant, but that is small compared to recent swings in gas prices caused by volatility in oil prices.72 A carbon tax at that level would generate revenues beginning at 0.6–0.8 percent of GDP and rising by an additional 0.1 percentage point by the early 2020s.73

A major problem with a carbon tax is that it is regressive. Although rich people consume more energy than poor people (they typically have larger houses with higher heating costs, for example), poor people have to devote a larger share of their income to energy (because everyone needs a basic amount of heat, electricity, and transportation).74 The point of a carbon tax, however, is to counteract the social costs of greenhouse gas emissions while raising additional revenue to reduce deficits—not to change the distribution of income in society. Therefore, the carbon tax should ideally be made “distribution neutral”: that is, it should increase everyone’s total taxes by the same percentage amount.75 This can be done by modifying income tax rates (raising them at the high end and lowering them at the low end) to neutralize the regressive impact of a carbon tax.76 As an alternative, if raising income tax rates turns out to be politically impossible, up to one-half of the carbon tax revenues should be spent in the form of cash rebates to low-income households to cushion the impact of the tax.

A carbon tax could be implemented in two different ways. One is a direct tax on carbon, where, for example, each refinery has to pay the tax on each gallon of gasoline it produces. (That tax would be passed on to drivers at the pump.) The other is setting a cap on total emissions and auctioning off the right to emit greenhouse gases; in that case, each refinery would have to buy enough emission permits to cover the gasoline it produces, so in the end there would effectively be a tax on each ton of emissions. There has been extensive debate about which system is better; to simplify, one side argues that a direct tax is more efficient, the other that an emissions cap is more politically feasible.77 In practice, however, most of the features of one approach can be replicated in the other, depending on the details of how each is implemented.78 In our opinion, either approach would be a vast improvement over the current situation, both for economic incentives and for the federal budget.

Finally, a carbon tax would account for the greenhouse gases emitted by our cars, but not for all of the other social costs created by driving, which produces congestion, accidents, and local air pollution. In order to account for these externalities—costs to society that are not reflected in the cost of driving itself—taxes on gasoline would have to be about $1 per gallon, double their current level, or even higher.79 Increasing the federal gasoline tax by 50 cents per gallon would benefit society by encouraging people to drive less, reducing congestion, accidents, and air pollution, and would also increase tax revenues by about 0.3 percent of GDP.80 Alternatively, the gasoline tax could be made variable—higher when oil prices are low and lower when oil prices are high—in order to reduce volatility in gasoline prices.81 In any case, a gasoline tax is regressive for the same reasons a carbon tax is regressive, and so we recommend either modifying income tax rates to make it distribution neutral or spending up to half of the additional proceeds as rebates to lower-income households.

Our current deficit problems are largely the product of our financial sector. As discussed in chapter 3, the financial crisis of 2007–2009 and ensuing recession increased projected national debt levels by almost 50 percent of GDP. Subtracting 50 percent of GDP has a major impact on any projection of future national debt. If there were no financial crisis and the Bush tax cuts were allowed to expire, our long-term deficit problems would be small and manageable; even if the Bush tax cuts were extended, the long-term national debt would look uncomfortably large, but nothing like it seems today. In addition, the risk of another financial crisis—and the need for fiscal space to respond to such a crisis—is a major reason to worry about our current situation. For these reasons, policies that reduce the risk and impact on taxpayers of a financial crisis are crucial to our long-term fiscal health—even leaving aside any desire to make the financial sector pay for all the trouble it has caused.

We have previously argued that the most direct way to reduce the riskiness, concentration, excessive size, and political power of the financial sector is to impose hard limits on the size of financial institutions.82 A version of our proposal, however, was voted down in the Senate and appears even less likely to succeed today.83 There are many other ways that excessive risk taking in the financial sector can be curbed, such as increasing capital requirements for large financial institutions—those most likely to be bailed out in a crisis, and hence those most likely to take the most risks.84 Here we focus on ideas that can both reduce the incentives for financial institutions to engage in socially destructive behavior—like taking risks that only make sense because of the prospect of a government bailout—and raise additional revenues to reduce the deficit.

The first is a fee imposed on large financial institutions to compensate for the likely costs of future government rescues.85 Since our largest banks are even larger than they were in 2007, they are even more “too big to fail,” and it is virtually certain that they will require government support in a future crisis. That support should be given on less generous terms than during the recent crisis, but it will cost real money all the same. These too-big-to-fail institutions should have to pay a fee today based on their size and riskiness; for example, the more highly leveraged a bank, and hence the more vulnerable it is, the more it should have to pay. A fee that increases with leverage will also help counteract existing incentives for companies to take on too much debt. If properly designed, it will discourage financial institutions from taking on too much risk, which will reduce the threat they pose to the financial system. If designed solely to correct for the implicit government subsidy enjoyed by too-big-to-fail financial institutions, this fee could bring in close to 0.1 percent of GDP per year.86 In addition, it will improve our long-term fiscal situation by helping to protect future taxpayers from the consequences of future financial crises, which are virtually inevitable.

The second idea is a financial activities tax aimed at curbing excessive risk taking in the financial sector.87 Many financial institutions are highly leveraged (they have large amounts of debt relative to the money invested by shareholders), which gives them the incentive to engage in risky behavior: if things go well, shareholders and managers get to keep the profits, but if things go badly, some of the losses will be borne by creditors. These types of risks are like greenhouse gas emissions: good for the banks that take them but bad for society as a whole.88 In theory, the solution is to tax risk taking to the point that the financial sector will only produce the amount of risk that is optimal for society—but in isolation it is difficult or impossible to identify which risks are good and which are bad. One solution to this problem is to impose an additional tax on high profits earned by financial institutions, which will make highly risky strategies less attractive and thereby reduce risk taking. Such a tax would be assessed only on unusually high compensation (the difference between what highly paid employees make in the financial sector and what people with similar skills and experience make in other sectors) and on unusually high profits (above a level reflecting ordinary or even moderately high returns to capital). According to an estimate by economists at the IMF, this tax base would range between 0.7 percent and 2.8 percent of GDP, so a tax at a 10 percent rate could raise 0.1–0.3 percent of GDP.89 The major purpose of this tax, however, is not to reduce deficits, but to shift incentives in the financial sector away from levels of risk taking that are, on balance, bad for society. Together, these policies will help make the financial system safer and provide at least some of the funds necessary to cope with the next crisis.

The federal government spends money on a myriad of other programs ranging from educational grants to housing subsidies to medical and space research. We do not have the space (or the expertise) to review all of these programs in detail, but there are certainly places where the government could spend less money and increase economic efficiency.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are a classic (though complicated) example of a government program that distorts market outcomes. Before the recent financial crisis, Fannie and Freddie were “government-sponsored enterprises”—private companies subject to specific congressional mandates to support the housing market. They did this by buying mortgages from lenders, guaranteeing mortgages against default, and issuing securities backed by mortgages, all of which made it easier for banks and other lenders to make new housing loans. Because Fannie and Freddie were highly exposed to the mortgage market, they both failed when housing prices collapsed and were taken over by the government in 2008; they continue to buy and guarantee mortgages and to issue mortgage-backed securities. Currently, they charge less for guarantees than the private sector would charge; they do this in order to subsidize mortgages and keep the housing market going, and they can get away with it because, as wards of the federal government, they can borrow money cheaply. This policy lowers the cost of borrowing, encouraging families to go more deeply into debt; because it makes it easier to take out a big mortgage, it also inflates the price of houses.

Although Fannie and Freddie were relatively modest contributors to the financial frenzy that created the housing bubble, the experience of the last decade should have demonstrated the dangers of government policies that promote homeownership by subsidizing debt.90 We think that Fannie and Freddie should gradually raise their guarantee fees to levels competitive with those of the private sector, which will increase their revenues and improve their long-term financial position while reducing this distortion in the price of mortgages.91 We also recommend gradually lowering the limits on the mortgages that Fannie and Freddie are allowed to buy or guarantee, which will reduce government housing subsidies further, particularly for people who buy more expensive houses.92

Another complicated spending program that distorts economic decisions is our system of agricultural subsidies. In 2010, the Department of Agriculture distributed over $15 billion in subsidies through several overlapping programs.93 Direct payments give people cash based on how much their land used to produce (whether or not it is still used as farmland); counter-cyclical payments pay farmers when crop prices fall below a target, effectively locking in a minimum price; marketing loans also guarantee a minimum price while allowing farmers to benefit if prices are higher than the target; crop insurance protects them from losses due to natural causes, with premiums heavily subsidized by the government; and in addition to crop insurance, the government also makes direct disaster payments to farmers affected by bad weather and other natural phenomena.94

These policies encourage overproduction of subsidized crops such as corn and soybeans (since the government absorbs the risk that prices will be low)—which is one reason why the American diet includes so much high-fructose corn syrup.95 Government subsidies also help American companies export corn, cotton, and other crops cheaply, undercutting farmers in developing countries.96 In 2005, the World Trade Organization ruled against the United States in a case brought by Brazil challenging U.S. cotton subsidies; in response, the federal government is now paying over $100 million per year in subsidies to Brazilian cotton growers.97 While farm subsidies are often portrayed as a way to protect small family farms, an increasing share of the money goes to the largest farms (and another chunk goes to people who don’t farm at all).98 In this context, farm subsidies could be dramatically scaled back, leaving unsubsidized insurance markets and commodity derivatives to protect most farmers from natural disasters and extreme price swings.99 If preserving small family farms is an important policy goal, then the government could provide them with subsidized crop insurance and assistance in hedging transactions.

A more coherent energy policy, as described above, would also allow the government to cut back on transportation subsidies. For example, the federal budget currently allocates about $4 billion per year on subsidies to intercity rail service and another $2 billion per year to subsidies for building mass transit systems.100 While long-distance and mass transit train systems would help reduce air pollution, slow the rate of climate change, and ease congestion on roads, both a carbon tax and a higher gasoline tax should make them more competitive compared to driving and flying, thus reducing the need for subsidies. The federal government also subsidizes air travel in various ways. For example, new fees introduced after September 11, 2001, cover less than half of federal spending on aviation security, and corporate and personal aircraft do not pay their share of air traffic control expenses.101

Although the potential benefits are often exaggerated, the federal government could also save money simply by making its operations more efficient. For example, the government currently spends about $540 billion per year on goods and services. In 2009, about $170 billion in spending commitments were made in noncompetitive contracts, and additional billions were spent in “competitive” contracts where only one bid was received. In some cases, this is unavoidable in the short term, because there may be only one qualified supplier for a given specialized product or service. The Government Accountability Office, however, has identified cases where federal agencies could use competitive processes to reduce costs.102 The federal government could also follow the lead of many large corporations in centralizing procurement decisions in order to increase its buying power and obtain lower prices.103

Market forces should be able to produce a reasonable amount of home mortgages or corn. By contrast, a free market on its own will not produce enough public goods, such as education and basic research, because they generate benefits for society that are not captured by the people who pay for them (think of all the people who have benefited from the Internet, which was originally a Defense Department research project). For this reason we do not recommend withdrawing federal spending on education, although there may be ways to reduce waste and increase efficiency in the way that spending is delivered. Our future prosperity will depend on the productivity of our workforce, which largely depends on our educational system. Now, when our students rank twenty-fifth out of thirty-four OECD countries in math performance, is not the time to reduce government support for education.104 We also do not recommend cutbacks in safety net programs such as the National School Lunch Program, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (food stamps), or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. More than 15 percent of Americans live below the poverty line (about $22,000 for a family of four), the highest level since 1993;105 in 2009, 15 percent couldn’t afford to buy enough food, the highest level since the Census Bureau began collecting this information in the late 1990s.106 Although providing basic subsistence to poor people may violate some theoretical norm of economic efficiency, we believe it falls well within the government’s responsibility to protect its citizens from extreme misery and insecurity.

Domestic spending (other than Social Security and health care) is fragmented across many departments, agencies, and programs, of which we have only touched on a few. The cutbacks to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and to agricultural subsidies described above together would reduce spending by about 0.1 percent of GDP.107 Spending cuts in areas such as transportation subsidies and through greater procurement efficiency will be necessary to bring discretionary spending down to the levels required by the Budget Control Act of 2011; since our projections already assume that Congress complies with that law, we do not count these spending cuts toward our long-term deficit reduction target.108

One of the major achievements of the Reagan administration was the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which simplified the tax code by eliminating a host of loopholes. Since then, however, Congress has steadily created new tax breaks, which reduce tax revenues, increase administrative costs, and give rise to complicated tax avoidance behavior—effort and expenses that serve no purpose other than reducing taxes. Many of these exemptions, deductions, or other loopholes are tax expenditures—the equivalent of government spending programs, since people receive cash (in the form of lower taxes) for engaging in certain activities (such as taking out mortgages). These tax ex- penditures, broadly defined, reduce federal tax revenue by about $1.2 trillion, or 7 percent of GDP.109

Eliminating or reducing tax expenditures presents a rare “win-win” opportunity: it increases revenues (reducing the deficit) without increasing tax rates, preserving the incentives to work and to save; and it increases economic efficiency by reducing government influence on individuals’ decisions—a point argued by Martin Feldstein, a chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Reagan.110 Some of the higher revenues could theoretically be set aside to lower tax rates, as suggested by some proponents of comprehensive tax reform or a “flat tax.” This would only be prudent, however, if the Bush tax cuts were allowed to expire; otherwise the revenues from eliminating tax breaks will be needed to reduce long-term deficits.111 In some cases, tax expenditures encourage behavior that may be beneficial for society—such as saving for retirement—so they need to be considered one at a time. Because there are far too many questionable tax provisions to review in this section, we only discuss a few proposals that will have the largest impact on both tax revenues and economic efficiency.

The single largest tax expenditure is the exclusion for employer-sponsored health benefits; as discussed above, we believe this exclusion should be phased out. The second largest is the deduction for mortgage interest on residences (and vacation homes, for the lucky). This deduction, which will lower tax revenues by about $99 billion in 2012, is the poster child for everything that is wrong with tax expenditures.112 By reducing the real cost of a mortgage, it encourages people to borrow more money to buy bigger houses, contributing to the excessive household debt that helped produce the financial crisis. Because the value of the deduction depends on the size of your loan and the tax bracket you are in, it disproportionately benefits the wealthy.113 The mortgage interest deduction does a bad job at its supposed objective of encouraging homeownership because the people who are most likely to be on the fence between owning and renting—low- to middle-income families—gain the least from it.114 (In particular, if you don’t have enough other deductions to make itemization worthwhile, you get nothing from the mortgage interest deduction.) Finally, in the wake of the housing bubble and financial crisis, it’s less apparent than ever that using government policies to increase homeownership is a good idea to begin with.

For these reasons, we would prefer that the mortgage interest deduction did not exist. Unfortunately, eliminating it now could cause a severe economic shock: without it, families will not be able to pay as much for houses, and the value of all houses will fall, making it harder for homeowners to refinance and increasing foreclosure rates. Therefore, we recommend partially phasing out the deduction over several years and then letting it fade away over several decades. Today, the deduction is available on $1.1 million of mortgage debt. We would reduce that limit to $1 million in 2014 and gradually reduce it to $400,000 by 2020; since less than 10 percent of existing homes in the United States sell for more than $500,000 today, the vast majority of homes should not suffer immediate price declines.115 This would increase tax revenues by about 0.2 percent of GDP in 2020, and by 0.3 percent in 2030.116

Another poorly designed subsidy hidden in the tax code is the exemption for interest on state and local bonds, which will cost the Treasury $50 billion in 2012.117 This is a transfer from the federal government to state and local governments because the tax exemption means that investors will accept lower rates of interest on their bonds. For technical reasons, however, about one-third of the subsidy winds up in the hands of the investors who buy these bonds.118 If the tax exemption were replaced by a direct subsidy to the issuers of state and local bonds, the federal government could provide the same amount of assistance for only two-thirds of the cost. This change would increase tax revenues by about 0.1 percent of GDP, beginning later this decade.119

The federal government also helps state and local governments through the deduction for state and local taxes, which will reduce revenues by $74 billion in 2012.120 The deduction means that the Treasury Department is essentially paying part of your state and local taxes, making it easier for state and local governments to raise money. This is an inefficient subsidy because, on a per capita basis, more money goes to states and towns that have higher taxes, and more money goes to states and towns that have more rich people (since this tax break only benefits people who itemize their deductions, and these people tend to be wealthier than others). In particular, this deduction benefits towns with expensive houses much more than towns with inexpensive houses because the former collect much more in property taxes than the latter. We recommend phasing out this deduction entirely and converting half of the new revenues into grants to states and localities; state and local governments could then decide whether to use the grants to lower taxes or increase services. After accounting for the grants, eliminating this tax break would increase revenues by about 0.2 percent of GDP.121

Not only does the federal government subsidize state and local governments, but it also subsidizes nonprofit organizations through the tax deduction for charitable contributions. If you are in the 35 percent tax bracket, out of every dollar you donate, the government is actually paying 35 cents. This tax deduction is occasionally defended as a way of patching our meager social safety net, but homeless shelters and soup kitchens compete for donations with the Metropolitan Opera, Harvard University, and even politically oriented think tanks.122 In effect, the federal government spends $53 billion (in 2012) on nonprofit organizations—but lets rich people (the ones who make most of the contributions) decide who gets the money. There are many ways to scale back this subsidy that would have a small impact on nonprofit organizations. For example, only allowing the deduction for total donations above 2 percent of adjusted gross income (a policy applied to some other deductions) would increase tax revenues by 0.1 percent of GDP but reduce total charitable contributions by only 1 percent. Put another way, the federal government (meaning future taxpayers) would gain five times as much as charities would lose.123

Another large tax expenditure is preferential tax rates on income from investments, including capital gains (profits from selling assets for more than they cost) and dividends (payments made by corporations to their shareholders). Taxation of investment income is a complex problem that has occupied lawyers and economists for decades because it has no perfect solution. Taxing capital gains distorts economic choices by discouraging people from selling assets they would otherwise want to sell.124 Because corporations already pay tax on their profits, taxing dividends on the individual level constitutes double taxation. One argument for a lower (but not zero) tax rate on capital gains is that some of the “gains” are really due to inflation, not real investment returns. But a lower rate on capital gains encourages people to engage in expensive tax avoidance strategies to convert ordinary income into capital gains. In addition, effective taxes on capital gains are already artificially low (even if they are taxed at the same rate as other income) since people can defer them indefinitely by waiting to sell their assets.125

The main economic argument for a lower tax rate on capital gains is that it encourages saving (by increasing the after-tax return on saving), which in turn encourages investment and economic growth. As discussed in chapter 6, however, the empirical evidence that higher taxes on capital gains reduce savings and economic growth is weak. The case for lower capital gains taxes becomes even weaker when they have the effect of increasing deficits, because any increase in private saving is offset by an increase in government borrowing. We have had a lower tax rate on capital gains than on ordinary income for most of the history of the income tax, but the 15 percent rate set by the 2003 tax cut is remarkably low; from the 1930s until 2003, the maximum capital gains rate never fell below 20 percent.126 And the benefits of lower taxes on investments are highly skewed toward the wealthy: 96 percent of the total benefits are claimed by households making more than $100,000 per year, with 67 percent of the benefits going to households making more than $1 million per year.127

Given the large deficits we face today and in the foreseeable future, it makes sense to increase capital gains tax rates in order to reduce government borrowing; any reduction in personal saving is likely to be at least offset by the increase in government saving.128 We propose increasing the maximum rate on capital gains and dividends to 28 percent, the level that applied from the Tax Reform Act of 1986 until the 1997 tax cut129 and slightly above the median level for the entire post–World War II period (25 percent).130 In the short term, a higher capital gains tax rate could make people less willing to sell their assets, reducing tax revenues. In the long run, however, a permanent change in tax rates should have little impact on actual asset sales, since most assets are sold eventually.131 Leaving aside short-term fluctuations, this change should increase tax revenues by about 0.3 percent of GDP.132

Another problem with the current taxation of capital gains is called “stepped‑up basis” at death. If you die and leave your assets to your heirs, no one ever pays tax on any appreciation that occurred during your lifetime. This reduces tax revenues and exacerbates the “lock-in” problem: people who would otherwise sell assets have a powerful incentive to hold on to them until they die. We do not see why families should pay lower taxes on investment profits simply because they can afford to pass assets from one generation to the next. One rationale for stepped‑up basis was that it may be hard for heirs to figure out how much the deceased person originally paid for an asset, but today this should be an easily solvable problem, at least for the financial assets and real estate that produce a large portion of capital gains. This tax expenditure will cost the Treasury Department $61 billion in 2012; eliminating it should increase tax revenues by about 0.5 percent of GDP.133 We also propose to scale back another capital gains tax break that exempts profits from the sale of a house. The amount of profit exempted from taxes should be gradually reduced from $500,000 (for couples) to $100,000. This would still protect most middle-income families from having to pay taxes on gains that are due solely to inflation while reducing the subsidy given to the rich. We estimate that reducing this tax expenditure would increase tax revenues by another 0.1 percent of GDP.134

Not all tax expenditures are equally bad. The various tax preferences for pension plans and retirement accounts (401(k) plans, IRAs, and so on) together cost $147 billion, but these provisions are designed to encourage saving in general and retirement saving in particular—both things that Americans currently do not do enough of. Other commonly cited tax expenditures, such as the child tax credit and the earned income tax credit, are more like features that modify the distribution of the income tax based on ability to pay than like covert spending programs.135 But besides the examples discussed above, there are plenty of other tax expenditures of questionable value, such as the tax exemption for life insurance products.

Since some tax expenditures are better than others, we prefer to review them on their individual “merits.” Politically, however, this may be impossible because each one benefits a particular interest group that will defend it tooth and nail: the mortgage and real estate industries for the mortgage interest deduction, the life insurance industry for the life insurance exemption, and so on. Other people and groups have proposed across-the-board solutions. President Obama’s bipartisan National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform recommended simply eliminating all tax expenditures or, alternatively, eliminating all of them except the earned income tax credit, the child tax credit, and reduced versions of a few other popular tax breaks.136 Eliminating all tax expenditures would increase revenues by something on the order of 7 percent of GDP, solving our deficit problems for several decades in a single stroke, and would generally be progressive, since the rich benefit more from tax expenditures overall. But it could also cause severe economic disruptions as housing prices fall, retirement savings rates fall, low-income families lose the earned income tax credit, and nonprofit organizations are forced to contract.

Another nearly comprehensive approach that would have a less drastic impact on the economy is limiting the amount by which any family can benefit from tax deductions. Martin Feldstein, Daniel Feenberg, and Maya MacGuineas have estimated that capping benefits from tax expenditures at 2 percent of each household’s income would have increased tax revenues by $278 billion in 2011, or 1.8 percent of GDP.g 137 This proposal would increase revenues and reduce distortions, but would hit all tax expenditures equally, regardless of their redeeming features. In addition, it would constitute a flat tax increase, since all income groups would see their taxes go up by roughly the same percentage of their income;138 so while it might make up much of the revenue lost in the Bush tax cuts, the overall tax system would end up being much less progressive than before 2001. A more progressive alternative is limiting the percentage by which deductions can be used to reduce taxes. Today, a $1,000 deduction is worth $350 to someone in the top (35 percent) tax bracket but only $100 to someone in the lowest (10 percent) bracket. Limiting the value of itemized deductions to 15 percent of the deduction amount, regardless of tax bracket, would increase tax revenues by 0.7 percent of GDP per year;139 this change would only affect people who are not in the lowest tax bracket and who itemize their deductions, so it would be somewhat progressive. It would also avoid the need to debate the merits of individual tax expenditures (but, unfortunately, would not affect several tax expenditures that do not appear as deductions, such as lower tax rates on capital gains).

Through some combination of these proposals, individual income tax expenditures (other than the employer health plan exclusion) could be reduced by 1–2 percent of GDP while maintaining existing incentives to work and save and avoiding a severe economic shock. Much larger revenue increases are possible if we are willing to eliminate tax expenditures that encourage saving (such as tax preferences for retirement accounts) or to undergo short-term economic risks (such as by completely eliminating the mortgage interest deduction).

The corporate income tax offers fewer opportunities to raise revenue while reducing distortions because business tax expenditures in aggregate are much smaller than individual tax expenditures. Still, the tax code includes over $30 billion worth of tax breaks targeted at particular industries such as energy (both fossil fuels and renewables), timber, agriculture, or manufacturers.140 Eliminating all of these tax expenditures would increase revenues by about 0.2 percent of GDP without raising tax rates, while reducing economic distortions created by government policies that favor one industry over another industry or one group of companies over another group. There are other, more fundamental problems with our corporate tax system: among other things, it encourages companies to take on more debt and to leave their earnings overseas for as long as possible. But while solutions to these problems are desirable on other grounds, they are unlikely to raise additional tax revenues and help solve our long-term budgetary problems.141

American families do not save a lot of money. The household savings rate—the percentage of after-tax income that is not consumed in purchases of goods and services—averaged 9.6 percent in the 1970s and then declined steadily from the early 1980s until the peak of the housing bubble in 2005–2006, falling as low as 1.5 percent.142 This long-term decline in savings probably has multiple causes. Many middle-class families, which have seen stagnant wages for most of the past three decades, became increasingly reliant on credit to maintain or improve their standard of living; while inflation has been low since the 1990s, the rising prices of health care and education forced many families to take on additional debt; financial innovations, such as the exotic mortgages that fueled the housing bubble, made it easier for people to borrow money out of proportion to their income; and the bubble itself, by making people richer on paper, encouraged them to consume more and worry less about saving.143 Low savings and high debts hurt our economy in several ways. The vast increase in household debt not only helped inflate the recent housing bubble but also made many families acutely vulnerable to the ensuing crash, deepening the recession; insufficient savings mean that many people are not adequately prepared for retirement (making them that much more dependent on Social Security and Medicare); and less household saving means that less money is available for productive investment by businesses, which can hurt long-term economic growth and increases our reliance on borrowing from overseas.

The benefits of encouraging savings, or at least not discouraging savings, are one reason why many experts have suggested shifting from an income tax system (where we pay tax on money when we make it) partially or entirely to a consumption tax system (where we pay tax on money when we spend it).144 The basic reason is that an income tax encourages people to spend their money today rather than saving it for tomorrow, while a consumption tax does not affect decisions about when to spend.145 Of course, adding a new consumption tax without reducing other taxes would not increase household savings. But the conundrum we face is that if the Bush income tax cuts are made permanent, we will need to either increase tax revenues somehow or scale back the social insurance system for the middle class. If we have to raise additional tax revenues, we should do so in a way that is efficient—that distorts economic choices as little as possible—and that best supports long-term growth.

These considerations imply that some of our long-term budget gap should be filled through a value-added tax (VAT), a type of consumption tax that is currently used (typically alongside an income tax) by every developed country except the United States.146 A value-added tax does not affect companies’ decisions about how to do business, and, unlike an income tax, does not discourage people from saving. Because it is applied to a very broad tax base—almost all final sales of goods and services to consumers—a relatively low tax rate can generate large amounts of revenue. For example, a VAT of 5 percent with only a small number of exclusions (education, government-paid health care, charitable services, and government services) could bring in 1.7 percent of GDP in revenues.147

The major problem with a value-added tax is that it is regressive: households with lower incomes pay a larger share of their incomes because high-income households tend to save more and consume less. This discrepancy can be dramatic, with bottom-quintile households paying an effective tax rate five times as high as top-quintile households (although other ways of measuring the distribution of the tax burden yield different results).148 As with a carbon tax, our preferred solution is to adjust the income tax to make the introduction of a VAT distribution neutral—increasing income tax rates at the high end and lowering them at the low end (and expanding tax credits to benefit households that pay no income tax) so that each income group sees its taxes go up by the same percentage. (Households that rely primarily on Social Security would be protected from a VAT—which will create a one-time increase in prices when it is introduced—by the fact that Social Security benefits are indexed for inflation.) Alternatively, one-half of the proceeds of a value-added tax could be used to cushion the impact of the tax on low-income households, in the form of either lower income or payroll taxes or cash rebates. (In this case, we could still reduce the deficit by 1.7 percent of GDP simply by doubling the tax rate.)

Introducing a value-added tax, along with our earlier recommendations to scale back tax expenditures, would reduce the long-term budget deficit while minimizing the distortions introduced by our tax system. It would not, however, do much to make the tax code less complicated and more efficient in general—something tax experts have been recommending for a long time. The central task at hand, however, is dealing with our growing national debt, and while comprehensive tax reform has its own merits, we do not believe it should stand in the way of reducing the federal government’s long-term budget deficits.