What do we mean by health? The World Health Organization offered an answer to this question back in 1946. “Health,” said the coordinating health authority for the United Nations, “is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” That’s a great definition, and it is a lofty goal—one we all hope to achieve. The question is how.

Hippocrates, the legendary physician of classical Greece known as the father of medicine, formulated an answer that has come down to us in its Latin form as vis medicatrix naturae, the healing power of nature—the idea that if organisms are provided the right environment, diet, and lifestyle support, they can heal themselves. In our day, the idea has been recast through the lens of the genomic revolution as our ability to shape the way our environment influences the expression of our genes, which in turn shapes our individual health and disease patterns.

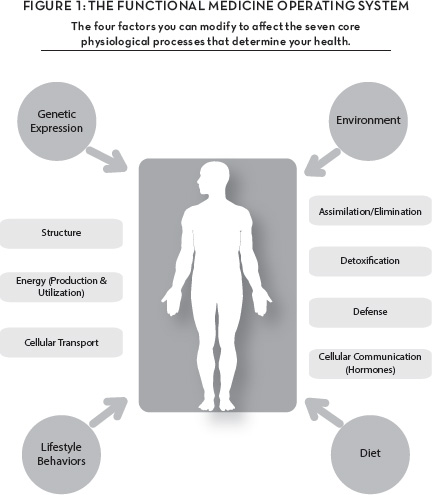

Everything laid out in the previous chapters of this book—the discoveries of the genomic revolution and the wisdom captured by looking at chronic illness from a systems biology perspective—comes down to putting that idea to work. Its practical application is the functional medicine model that is our era’s revolution in health care. Patient-centered, the model requires that the individual participate fully in managing his or her health. The idea is simple: by creating a personalized health-management program that sets out changes in diet, lifestyle, and environment, we can directly affect how our genes are expressed and thus the patterns of our health.

That’s what you’re about to do. With the help and support of your chosen health practitioner, you’re about to design and execute your own personalized plan to address any health problems you have and to live in a way that optimizes your genetic potential. This chapter gets you started. It prompts you to look at your own health and start putting together the tools to manage it in a whole new way.

Not just new—different as well. In the previous chapters of this book, you have absorbed concepts of medical thinking that diverge markedly from what you’ve known up to now, and you’re about to start applying health interventions and therapies that are likely considerably different from what you’re used to. It makes sense, therefore, to review the key tenets of this new thinking before you undertake the new interventions. Basically, they come down to these five.

1. Our health is not predetermined by our genes. No single gene controls the presence or absence of a chronic disease. Our pattern of health and illness is determined by how families of genes are expressed, and that expression can be influenced and indeed altered by a range of lifestyle, diet, and environmental factors—exercise, stress, pollutants, radiation, specific foods, phytonutrients, and more—that send signals to the cells of our body.

2. Chronic illness is a result of an imbalance in one or more of the core physiological processes. Such an imbalance derives from the interaction between our genome and our lifestyle, diet, and environment. The imbalance alters function. Over time, that altered function is evidenced in specific signs and symptoms that we collectively label a disease. Changes to lifestyle, diet, and environment can bring our core physiological processes back into balance.

3. The absence of illness does not necessarily equate to the presence of wellness. A diagnosis of chronic illness comes after a period of declining function. If your ability to function has not yet begun to decline or has only just begun to decline, now is the best time to execute a personalized lifestyle intervention, for now is when it will have the greatest positive impact on your health.

4. Each person’s physiological response to lifestyle, dietary, and environmental factors is unique to his or her genetic makeup. Every individual’s genetic makeup is unique, and each of us therefore experiences unique responses to lifestyle, diet, and environment. A lifestyle, diet, and environment that are optimal for one individual might be poison for another.

5. Drugs effective for the management of acute disease may be inappropriate for the long-term management of chronic illness. Most pharmaceutical drugs are designed for potency in blocking a specific step in the complex physiological network associated with the target condition of ill health. Over time, however, their potency may have a collateral effect off-target, with potential adverse impact. Since most chronic illness needs to be managed for the long term, the safest use of drugs will be as late as possible in the progression of the symptoms of illness and in the lowest dose possible to maintain healthy function.

This is the background against which the functional medicine approach of personalized lifestyle health care has been designed. It focuses on treating the cause of a chronic illness—that is, imbalances in the core physiological processes—not the symptoms and signs that are the effects of the cause.

But the approach is not without precedent. Similar underlying tenets form the foundation of traditional Chinese medicine and of India’s Ayurvedic practices. Indeed, long before anything was known about cellular biology, genetics, or pathology, Eastern medical practitioners, through observation, embraced concepts very similar to those we apply today in functional medicine. One of the most gratifying aspects of my role as someone carrying the message of functional medicine around the world is to witness a growing movement to integrate Western and Eastern medical thinking and to consolidate the best practices of both. It is exciting to see how the new ideas born of the genomic revolution are reframing old observations and creating a new medicine in which the individual can take the best of knowledge and experience from many perspectives.

Here again is how we put it all together in our functional medicine operating model.

THE TOOLS OF PERSONALIZED HEALTH MANAGEMENT

What are the capabilities available to you to put the new medicine into effect? We’ve talked about them throughout this book—lifestyle, diet, environment. They’re the tools of health management, and we all own them. Everyone has a lifestyle—a set of behaviors and habits that mark how we live. Everyone has a diet or way of eating. And everyone lives in an environment; more precisely, everyone lives in a range of environments, from big categories such as which hemisphere you live in, whether in a hot or cold climate, whether in a developed or developing nation, city or country, mountain or shore, etc., to the more tightly defined environments of your home, workplace, amenities, and the like. That all three of these factors—lifestyle, diet, environment—play significant roles in determining how our genes are expressed and how our health is shaped over time may seem obvious. But it is not. It is as revolutionary a concept in medical thinking as the idea that bacterial infection causes disease was at the turn of the last century—and will have just as great an impact on medical treatment.

So the decisions you make concerning changes to these three parts of your life can be significant, which is why it’s important to make those decisions within a framework of criteria about what your decisions can and cannot affect.

DIET

Let’s start with diet because food is the one thing we all think, probably rightly, that we can most definitely control. Moreover, food is a cornerstone of the personalized program; in few other areas is it as clear as it is in this area—literally, as we’ve noted before—that one man’s meat is another man’s poison: that the foods that bring health to one individual can be a health disaster for another. Food also has a particularly critical role among the three factors of our plan—environment, diet, lifestyle—because we have to eat. It’s a survival essential.

And we know—because we hear it, read it, have it shouted at us on TV—that we should eat a varied diet and in moderate portions. What has become true for many of us in twenty-first-century America is that too many of us are malnourished—not from eating too little, but rather from eating too much of too little. It is called overconsumptive undernutrition, and it is not a deficiency of calories but a surfeit of empty calories, the kind—as you have learned—that send messages of alarm and danger to our genes. This is the malnutrition characterized by obesity, diabetes, heart disease, osteoporosis, dementia, and other chronic illnesses associated with inflammation, which can of course alter all seven core physiological processes.

So the proper diet for you will first and foremost provide adequate amounts of all the essential nutrients that meet your needs based on your genes, as evidenced in the process imbalances you’ve identified. It will also be satisfying to your taste, will be a pleasure and comfort to eat, and will adhere to the following shoulds and shouldn’ts.

| Your Diet Should . . . | Your Diet Should Not . . . | |

| have a low glycemic load | raise blood sugar or insulin rapidly after eating | |

| contain a proper balance of omega-3 oils | contain trans fats or partially hydrogenated vegetable oils | |

| provide high levels of phytonutrients aimed at supporting your own healthy genetic expression | contain allergy- or inflammation-inducing foods or ingredients | |

| contain higher levels of specific nutrients necessary to support individual needs | contain empty-calorie snack foods | |

| contain components that help support a healthy balance of enteric microflora | contain overly processed low-fiber foods |

In general, of course, we are talking about what is generally known as the Mediterranean diet as the baseline of healthy eating. This is a way of eating that incorporates all the shoulds and shouldn’ts that will guide your personalized plan. It contains a variety of lean proteins from both animal and vegetable products. It is low in sugars and in such processed foods as white flour products. It contains adequate amounts of whole fruits, vegetables, legumes, rice, and spices to meet phytonutrient needs, and it has enough foods containing omega-3 oils to provide a balance of fats.

Study after study has confirmed the efficacy of this way of eating as a baseline for good health. One of the most interesting studies, aimed at evaluating the long-term health impact of a Mediterranean diet, is the Healthy Aging Longitudinal in Europe study, HALE, which reviewed all-cause mortality in 1,507 apparently healthy seventy- to ninety-year-old men and women in eleven western European countries over a ten-year period. The results, published in 2004, showed conclusively that study participants had a death rate 50 percent lower than that of people who did not follow this way of eating or practice similar healthy-lifestyle habits.

A brief aside here: The lack of press coverage about this study makes you wonder about priorities. If a pill had been developed that could reduce death from all causes by half in a population of seventy- to ninety-year-olds, it likely would have been a top headline for weeks, with every senior citizen on earth lining up to get the prescription. The prescription here is a way of eating, and it seems to elicit only indifference from the world’s media.

In any event, HALE joins a long list of scientific evidence that the Mediterranean way of eating makes the perfect baseline for positive health outcomes. Only one more ingredient needs to be added, and that is the personalization that should inform your own health-management plan. Use the Mediterranean-diet baseline to meet the should and shouldn’t criteria for a general diet plan, then add or subtract the specific foods to meet your own nutritional requirements or avoid adverse immune response, and that will be your optimal plan.

LIFESTYLE

Obviously, this is a huge area. It embraces the personal habits we often label “recreational”; the level and content of your exercise activity; and the allostatic load of stress you may be carrying that is affecting your physiology and function.

Of the first of these, there is really no need to add to what is by now well known: smoking kills; alcohol and drug abuse mess up your life very badly—and then kill. So such habits are to be avoided.

Exercise is so extremely important to all aspects of health that, as with diet, it’s a good idea to start with a baseline of general criteria onto which you can add the specifics that personalize your exercise to your needs. Here are the shoulds and shouldn’ts of exercise activity:

| Your Exercise Program Should . . . | Your Exercise Program Shouldn’t . . . | |

| incorporate activities that build endurance, strength, and flexibility | exceed your physical capabilities | |

| bring your pulse and respiration into your aerobic training zone, calculated as 180 minus your age in years | produce serious muscle pain or joint strain | |

| have minimal impact on joints and muscles | total less than 120 minutes per week | |

| be something you do routinely 5 to 6 days a week | be only a “weekend warrior” activity of excessive physical demand without proper conditioning |

If there is a rock-bottom minimum of 120 minutes of exercise a week, the standard should be five to six sessions of at least 20 minutes per session five or six times a week. The excuse of not enough time is unwarranted. We find time every day to eat, drink, and breathe; exercise is as important to improving our core physiological processes as are those activities, and even with the “additional” time required to dress and undress, shower, warm up, cool down, etc., an exercise session amounts to no more than 4 percent of a day. If we compare the benefits it realizes—the positive messages it sends to your genes—that makes exercise the safest, most rewarding investment an individual can make.

You can enrich the investment further by adding to the baseline criteria more time or effort in any one of the end-goals—endurance, strength, or flexibility—that addresses your particular needs as evidenced in the process imbalances you’ve identified. More time spent in exercise never hurt anyone, but take care that the additional time does not exceed your capabilities at the time or add too much pressure or strain on muscles or joints.

The important third leg of the lifestyle component of your personalized health-management plan is dealing with your allostatic load. Clearly, no one can avoid stress altogether. We all occasionally feel the weight of the world on our shoulders, or encounter a back-breaking task, or feel we are going crazy from pressure of one sort or another. The metaphors are telling; allostatic load manifests itself as weight upon our physiology and ability to function.

What we now know is that it isn’t the stressor itself but rather our response to it that can amplify our cellular communication process to alarm status—and thereby affect other processes as well. We also know ways to deal with such responses on our part—through various techniques of relaxation and mindfulness that have been put forth over the years to alter the cellular communications process and dampen the alarm. The best advice I’ve heard on the subject came from one of the most formidable proponents of these ideas, Dr. Robert S. Eliot, the cardiologist and author of the best-selling 1985 book about type A personalities, Is It Worth Dying For? Eliot and I lectured together some years ago, and at dinner afterward, he crystallized his theory as follows: “There are two rules in life,” he said. “The first one is easy to understand; it says not to worry about the small stuff. The second one is more complicated; it says everything is the small stuff if it is going to kill us.”

I’ve incorporated that into my own process for keeping my allostatic load at bay, and I share it with you here in six steps.

1. Recognize that your allostatic load is affecting your health.

2. Identify the individual contributors to the load.

3. Differentiate those contributors that you have some control over versus those that you do not.

4. Focus on the contributors you can control; act to reduce their load.

5. Don’t sweat the small stuff, and anything that isn’t going to kill us is the small stuff.

6. Do sweat the big stuff, which is anything that adversely affects your health over the long term.

ENVIRONMENT

How can an individual control his or her environment when environment is the one thing we share with all the communities on the planet? Back in 1968, in an essay in the journal Science entitled “The Tragedy of the Commons,” ecologist Garrett Hardin of the University of California at Santa Barbara gave voice to that frustration. Air, water, and land, Hardin wrote, are considered “commons” and therefore can be exploited for individual good at the expense of the many. There is no technical solution to this, Hardin went on; rather, it requires a new way of thinking about personal responsibility—an understanding of our individual decisions and actions in the context of the influence they will have on the whole.

Yet once we have that first level of awareness about our personal impact on the environment and how it influences the commons, how is the individual to act? In the wake of the genomic revolution, we have guidelines for that—criteria for managing the environmental messages received by our genes.

• To eat organic foods as much as possible

• To avoid excessive sun exposure

• To drink purified water in metal or glass containers

• To use a headset with our cell phones

• To avoid processed foods and personal care products with synthetic ingredients

• To wash our hands before eating

• To avoid environments that support bad health habits

• To design our own environments to be safe places to live

Everyone can plant a garden. From the window box or shelf of herbs in a small apartment to the urban farming that is increasingly prevalent on building rooftops, every individual can find ways to take some control over his or her environment. It is always possible to send healthy messages to your genes rather than unhealthy ones. It is a matter of making the healthy choice, and in doing so, you also make a healthy contribution to our common environment.

SUPPLEMENTS AND PHARMACEUTICALS

Another key component of your personalized health-management program is the use of such nutritional supplements as nutraceuticals and medical foods,* over-the-counter therapies, and, where appropriate, prescription medications. All are tools that can influence your core processes and your health, and all belong in your health toolbox.

In the functional medicine revolution, dietary supplements, nutraceuticals, or medical foods are the therapies of choice to top up, as needed, an identified nutrient insufficiency in an individual’s personalized health-management plan, as we’ll discuss in more detail in the next chapter.

Where prescription pharmaceutical drugs are concerned, it’s essential, as most physicians will agree, that such therapies work in tandem with a patient’s lifestyle, diet, and environment and that they are prescribed to fit that context. One of the most stunning examples of what can happen if a physician is not aware of context is the understanding gained in recent years of the role of grapefruit juice. It has to be one of the more common household staples—a good-for-you fruit juice that families consume routinely. Yet we now know that this juice’s unique array of phytonutrients can profoundly affect the metabolism of some widely prescribed drugs. It increases the blood levels in women taking certain birth control pills and alters the effect of those pills. A flavonoid it contains, naringenin, reduces the metabolism of cyclosporine, a drug prescribed after kidney transplant surgery to prevent transplant rejection, and keeps it in the blood longer. These findings remind us again how diet can affect pharmaceuticals and why the control of lifestyle, diet, and environment is so important in any program designed to treat chronic illness.

If you’re taking prescription medications at the time you initiate your personalized health-management plan, the likelihood is that your medication doses will in time be reduced or even eliminated as the imbalances in your core physiological processes are rectified. But be sure your prescribing health-care practitioner is aware of all your factors of lifestyle, diet, and environment that may affect or be affected by the drugs.

THE TWELVE-WEEK TIME FRAME

Finally, why do we need to give a personalized health-management plan twelve weeks? Years of experience and many clinical studies make it pretty clear that this is the average time it takes to make a real change to your cellular biology and patterns of genetic expression. Yes, some people notice the benefits of personalized changes to lifestyle, diet, and environment right away; for others—remember Bruce?—progress is slow in coming.

Keep in mind that changing your lifestyle, diet, and environment is not like taking a drug to cure a specific symptom. The action of a pill or injection is to block or alter the function of one step in a complex physiological network. It can do this reasonably quickly in most cases, immediately in many cases. A program of change, however, is aimed at transforming a pattern of genetic expression and the nature of the control those genes exercise over the physiological network. Such change happens across a sequence of multiple changes—one change deriving from another in a chain of action and reaction—and it occurs over a longer period of time.

Here’s a suggestion: Right now, sit down and make a list of your health issues. What are the things that really bother you, the things you really, really want to change? Maybe it’s that you’re tired of feeling this tired so much of the time, or maybe you’re sick of taking four pills every morning with breakfast, or perhaps you want some improvement in—if not an end to—the joint pain you feel 24/7. Now rank these complaints for their severity on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the least onerous and 1 being the very worst. Keep the piece of paper handy so you can remember where you started. Take another look at it twelve weeks after you initiate your personalized health-management program.