1. Do you alternate between constipation and urgency?

2. Do you get indigestion?

3. Does your stool have an oily appearance?

4. Do you suffer from frequent intestinal gas or bloating?

5. Is stomach or intestinal pain a regular occurrence?

6. Do you ever get gastric reflux? Do you get it frequently?

7. Are headaches a common occurrence?

8. Are you allergic or sensitive to many foods?

9. After eating, do you find you experience joint or muscle pain?

10. Do you have bad breath?

11. Are you depressed? Subject to mood swings?

12. Do you have trouble keeping your weight under control even though you watch your diet?

13. Is your blood sugar elevated?

14. Do you suffer from kidney stones?

15. Is your blood pressure higher than it should be?

I experienced no small amount of anxiety just thinking about sitting down to write this chapter. To me, it is particularly important that I make clear to you, the reader, the understanding gained through recent scientific discoveries about our system of digestion and assimilation. It is so central to the functional medicine revolution that my self-imposed pressure to do justice to the explanation tied my stomach in knots for days as I approached my task.

And that, I realized, is precisely the point the chapter needs to bring home—namely, that it is no accident that anxiety has twisted my stomach into knots. Nor is it just a figure of speech. It is a medical fact, and the reason for it is the reality of the interconnections we’ve been talking about, more or less in the abstract, in the previous chapters and what those interconnections mean for a new way to approach chronic illness. The gastrointestinal system that carries out our functions of digestion and assimilation of food is connected to our nervous system, and both are linked through cells of the immune system. When you get butterflies in your stomach because the exam you’re taking counts for half the grade toward your professional license, or if you feel the urgent need for a rush call to the lavatory just seconds before a key presentation to your boss, it’s because your nervous system, now going into overdrive, has kicked off rhythmic muscle contractions in the intestines and has activated the more than 50 percent of the body’s whole immune system that is clustered around the gastrointestinal tract, stimulating substances that in turn send an alarm you feel right smack in your gut.

That’s why the gut is the starting point for an awful lot of chronic illnesses that seem to have nothing to do with the stomach; it’s the launch pad for numerous symptoms affecting parts of the body far distant from the gastrointestinal area. And vice versa. A glitch in the process of assimilation and elimination can make you sick, and because of the interconnections with the body’s nerves and immune mechanisms, all sorts of things can cause such a glitch.

So let’s begin by taking a look at this part of our physiology and at the process that takes place there.

THE PROCESS OF ASSIMILATION AND ELIMINATION

The intestinal tract in the adult human is some twenty-five to thirty feet long. That’s about midway between the longer intestinal tract of the cow and the shorter intestinal tract of the tiger. Herbivores like cows have long digestive systems because it is harder to absorb nutrients from plant foods than from animal foods; the herbivore tract needs more room to carry out the process than does the intestinal tract of a carnivore like the tiger. Since we humans are omnivores, we split the difference.

Food provides protein, carbohydrate, and fats—the nutrients from which we derive our cellular energy and construct the building blocks of our body. But for these nutrients to be used by the body they must be broken down through the process of digestion, and the waste products must then be excreted. The process begins in the mouth, where an enzyme called amylase, secreted in saliva, starts to break down carbs; it continues in the stomach, where other enzymes and acid released by specialized cells in the stomach lining start the breakdown of the large protein molecules into their smaller amino acid building blocks. The next step down the digestive system is through the duodenum, where bile is added to break down fats till they are absorbable. From here, the partially digested food, called the chyme, travels into the small and large intestines. The intestines are inhabited by many different types of bacteria, collectively known as enteric microflora; “enteric” simply means having to do with the intestines, and “microflora” are the many bacteria that make their home in our intestinal tract.

There are zillions of these enteric microflora—more in a single ounce of stool than there are stars in the known universe. In fact, there are many more bacterial cells in the intestinal tract than there are human cells in the whole body. These bacterial cells are very small compared with human cells, but their contribution to the overall health of the person can be quite significant.

For one thing, enteric microflora belong to one of three families of bacteria—symbiotic, commensal, or parasitic. Symbiotic bacteria enjoy a mutually beneficial relationship with us, commensal bacteria live in harmony with our bodies in relationships in which one of us benefits but neither is harmed, and parasitic bacteria get a free ride in our bodies and do us no good at all; in fact, their metabolism generates caustic substances that can harm us. Each of these families of enteric bacteria has its own preferential food to be metabolized. For example, the friendly bacteria in the intestinal tract—members of the symbiotic or commensal families—prefer certain fibers known as fructans, which come from plant foods. A diet too low in fiber can cause these friendly bacteria to die of starvation and be replaced by parasitic bacteria. The result can be such digestive complaints as irritable bowel syndrome, esophageal reflux, and chronic constipation. (One antidote is probiotics; another is specific kinds of fibers that support the growth of the friendly bacteria.)

As the digested food travels down the intestinal tract, its nutrients are constantly absorbed at different “stops” along the way. A disturbance in the process anywhere along this journey may reduce the absorption of specific nutrients, and that in turn can cause specific nutritional deficiencies—even when the overall diet contains adequate levels of the nutrients. We’ve seen this in patients taking certain antacid medications to manage their gastric reflux and acid stomach symptoms. A number of these patients develop a form of anemia and experience the kind of low energy associated with deficiencies in vitamin B12 and iron. Since adequate stomach acid secretion from the stomach lining is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12 and iron, suppressing acid secretion, as these antacids tend to do, can have these unintended adverse effects.

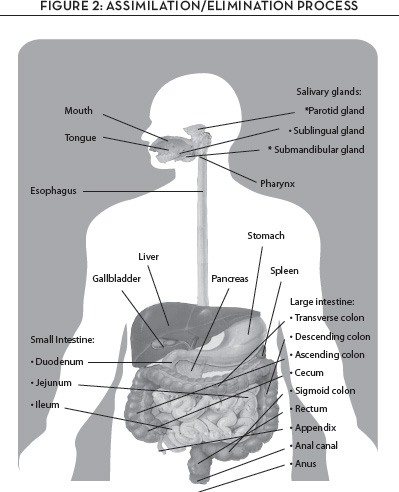

Once our food nutrients have been absorbed and converted to energy, the body needs to eliminate the waste products. The relevant organs in the elimination process are the intestinal tract and the kidneys and urinary bladder, which eliminate waste via urine and stool; the skin, which eliminates waste through perspiration; and the lungs, which exhale carbon dioxide and water vapor. Any glitch in the proper process of elimination can contribute to a range of chronic illnesses, and, because the system of assimilation and elimination is integrally linked with the immune system and the nervous system, the messages transmitted among these interconnected systems can reach to every part of the body, affecting our well-being in myriad ways. Figure 2 shows the anatomy through which the assimilation-elimination process works.

THE IMMUNE CONNECTION

If the whole of the intestinal tract were flattened out, its surface area would be about the size of a doubles tennis court. That surface is lined with millions of tiny folds called microvilli, and it is through the microvilli that nutrients are absorbed across the intestinal lining, transported from the inside of the tract to the rest of the body via specific transport processes in the intestinal cells.

On the other side of this lining sits the immune system of the intestinal tract, a system comprising more than half of the total immune system in the body as a whole. It is there not because there wasn’t any other place to put it, but because that’s where it has to be to defend the body from what might happen over a lifetime of ingesting nearly twenty-five tons of food items—“foreigners” to our body brought inside us from the external environment. Just keep in mind the assertion articulated by Linus Pauling that if you get the structure right the function will follow; the structure of the immune system of the gastrointestinal tract is what it is and where it is because of the importance of the function it must perform.

And its function is to serve as gatekeeper at the gastrointestinal barrier, ever alert to the arrival of foreign substances absorbed from our food that may be in some way harmful to our physiological functioning. The gastrointestinal immune system is precisely where it is so it can catch these substances before they create havoc in the body and can then process them into harmlessness.

It does this job by monitoring the metabolic substances produced by the enteric microflora. If the immune system senses that such a substance is harmful, it will react by increasing the number of alarm cells. When that happens, you feel it—as pain, or bloating, or diarrhea perhaps, or intestinal inflammation. But as those alarm cells hit the bloodstream and radiate outward, you might also feel it in places far removed from the gastrointestinal tract. Headache, joint pain, bad breath, muscle pain, skin and vision problems, even mood swings—symptoms that seem far away in every respect from the intestinal tract—may in fact be kicked off by the intestinal immune system. In fact, some of the toxic microflora in the gut can actually convert hormones like estrogen and testosterone into different forms that then produce different effects from those normally produced by the body’s natural hormones. No wonder mood swings are so confusing.

We now understand how all this happens. We owe it to the fact that the gut has its own nervous system. Dubbed “the second brain,” a term first coined by Columbia University research gastroenterologist Michael Gershon, this enteric nervous system consists of billions of neurons and is filled with the same kinds of neurotransmitters found in the brain in our skulls.

This “second brain” secretes messengers that communicate back and forth between the gut and the brain. Some of these messengers are hormones—cholecystokinins, ghrelins, secretins, gastrins, somatostatins, and more—produced by endocrine glands and sent forth into the bloodstream, while others are neurotransmitters released directly from nerve terminals in the brain’s central nervous system. One of the best known of these messenger substances is the hormone serotonin, known as the mood-elevating neurotransmitter. It may calm the brain, but the majority of the serotonin produced in the body comes from the gut, so that meddling with serotonin may also mean meddling with the gut. As it turns out, that’s exactly what happens with the class of pharmaceutical antidepressants known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, which increase serotonin levels in the nervous system. It has now been found that excessive serotonin availability is associated with increased risk of bone loss. Does this mean that these SSRI antidepressants are interacting with gastrointestinal function? The answer is yes; in fact, it has been reported that the use of SSRIs alters the important role that serotonin produced by the gut plays in influencing the balance between bone loss and bone formation. It also confirms the connection between the intestinal system and the nervous system.

Meanwhile, other messengers operate in other regions throughout the length of the gastrointestinal system. While serotonin affects mood, the hormone ghrelin, for example, affects appetite. Gastrointestinal inhibitory peptide influences insulin secretion and therefore blood sugar. Compared with ghrelin, cholecystokinin affects appetite in exactly the opposite way. Glucagon-like peptide 1, or GLP-1, regulates insulin secretion and also seems to influence the feeling of satiety in the brain. And so on, with other messengers affecting bone density, cardiovascular function, inflammatory responses, and more. The bottom line is simply that the channels of communication between the gut and the rest of the body—and certainly between the gut and the brain—teem with information flying back and forth, up and down, every which way, all profoundly influencing our physiology and our health.

A MATTER OF TASTE

Research into the connection between the brain and our process of assimilation and elimination is ongoing, and it is fascinating. A case in point is the work begun some time ago at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia by research neurologist Alan Hirsch. Hirsch’s work focused on understanding taste and smell and their relationship to human perception. At one point, he and his research group zeroed in on the effect of various nutrients on smell and taste—specifically on how nutrients influenced acuity, the keenness or sharpness of an individual’s smell and taste. A key finding was that zinc and a specific fat known as phosphatidylcholine, abbreviated PC, were effective in preserving taste and smell. Further study suggested that people who lose acuity of taste and smell may regain both with supplemental doses of these two nutrients. Some people have been reported to have regained the sense of taste and smell after such supplemental doses.

Later research went even further, finding a connection between the loss of taste and smell and early problems of the nervous system—specifically, with the particular nervous system problems that often presage Alzheimer’s and other neurological diseases; it meant that loss of taste and smell acuity could be used as a functional marker for aspects of nervous system function or dysfunction.

Taste, not surprisingly, starts on the tongue, where there are specific receptors for specific tastes—sweet, salty, bitter, sour, and a new taste termed “umami,” the taste activated by monosodium glutamate (MSG). What we perceive as taste sensations are the interactions of specific foods we eat with the taste receptors on our tongue. But not just on the tongue.

In the case of the bitter taste, for example, the surface receptors on specialized cells called L cells in the small intestine turn out to be identical to the bitter taste receptors on the tongue. In essence, our digestive system also “tastes” our food when the specific taste sensation—in this case, bitter—alters the gene expression of the L cell and its function. But this digestive system “tasting” sets up another reaction altogether. Here’s what happens.

When what we think of as a bitter-tasting substance is exposed to the L cells, it causes them to secrete the messenger mentioned a moment ago, glucagon-like peptide 1, into the bloodstream. GLP-1 is what is known as an integrin hormone; that means that it passes signals between a cell and its surroundings. In the case of GLP-1, that signaling stimulates the action of insulin, helping to control blood sugar levels after eating.

The bottom line of all this? Bitter-tasting foods can stimulate the L cells to release GLP-1 and in turn help to manage blood sugar and insulin levels. And indeed, certain foods that contain specific bitter substances have been shown to reduce blood sugar after eating. Bitter melon (Mormordica charantia), common hops, prickly pear cactus, and cow plant all do just that. Interestingly, all of them have historically been used by indigenous cultures to treat what we now call diabetes. But the discovery of how GLP-1 secretion improves blood sugar has also prompted the development of a class of medications for diabetes aimed at stimulating the release of insulin; one such is Byetta (exenetide), which increases GLP-1 activity.

In other words, what we eat and what we like to taste are significant in determining how our gastrointestinal system produces and secretes a stunning range of messenger substances affecting a stunning range of physiological functions—and our pattern of health and disease. In so many ways, food really is information, and it talks all the time to the genes regulating our core physiological processes.

Interestingly, we owe the start of our understanding of all this to a starfish off the coast of Sicily.

THE THORN IN THE STARFISH AND THE GUT-BRAIN CONNECTION

The man studying the starfish, the man who would teach us how the intestinal system influences so many health conditions, was Ilya I. Mechnikov, a Russian-born biologist, zoologist, and physician awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1908. Mechnikov would spend the bulk of his career as director of the prestigious Pasteur Institute in France, but it was in the late 1800s, while he was working at his own laboratory in Messina, Italy, that he made his most famous discovery. He was studying starfish larvae, and when he happened to insert a thorn into one larva, he observed a crowd of strange cells racing to the point of insertion and gathering there. Literally as Mechnikov watched, the cells engulfed and destroyed whatever tried to make its way in through that point of injury. Mechnikov dubbed these engulfing-and-destroying cells phagocytes, and he concluded that they live inside an organism for the precise purpose of ingesting—and thereby killing—what might be harmful to the organism.

We call this phenomenon innate immunity, and one of the things it explains is the cruel world in which we humans protect our physiology from infection. Simply put, there are these specialized white blood cells inside us that are on a constant search-and-destroy mission to recognize, chemically kill, and then consume foreign cells that enter the body. It’s what equips us to do battle against foreign invaders and potential cancer cells.

But Mechnikov’s observation about cellular immunity also explains how balance is maintained in the process of assimilation and elimination. In his 1907 book, The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies, Mechnikov asserts the important role of healthy intestinal microflora in achieving good health. The good health depends, he wrote, on a kind of peaceful coexistence among all the symbiotic bacteria in the intestinal tract—our own cells and tissue and all the microorganisms that live there as well—and phagocytes are key to keeping that peace. A disturbance of the peace—a microbial imbalance, known as dysbiosis—would equally disturb our good health. In a sense, the combination of Pasteur’s work on the origins of infectious disease and Mechnikov’s discovery of cellular immunity resulted in the recognition that the bacteria in the intestinal tract could be friends or foes. Too many foes anywhere in the process of assimilation-elimination would cause the gut to release various toxins that would range throughout the body, even as far as the brain.

That is why Mechnikov was an early advocate of yogurt in the diet. He saw it as a way to increase the number of friendly bacteria in the intestines and strengthen their effectiveness in preventing disease throughout the body and therefore in prolonging life. He saw intestinal health as integral to overall health.

What is interesting is that Mechnikov based this understanding, which would come to dominate medical thinking, on observation—coupled, of course, with his knowledge, experience, and sheer genius. What he did not know at the time, however, was exactly how it worked, how the gut produced and secreted messenger hormones and neurotransmitters that carry information throughout the body, from the gut to the brain and back again. But he sensed that the gastrointestinal system is in direct contact with the outside world—namely, with what we eat—and that the direct interaction between the microflora that live within our guts and what we ingest is central to our health. From there, it was an easy step to understanding that by changing the factors of that environment—that is, by eating more yogurt—we could influence the balance in the assimilation-elimination process and improve our health.

In truth, when Mechnikov first articulated his phagocytic theory, many prominent biologists, including Pasteur, were skeptical. In time, however, Pasteur summoned Mechnikov to be his deputy and successor at the Pasteur Institute, thereby awarding the theory his imprimatur. The 1908 Nobel sealed the deal, and the notion that many conditions of ill health, including those affecting the brain, could be treated by focusing on the gut became accepted medical wisdom for years to come—until a gruesome medical scandal subverted this wisdom and set back the course of medical progress in this area for eight decades.

TRAGEDY, SCANDAL, AND RETROGRESSION

Back in the 1920s, the largest mental hospital in the United States was the New Jersey State Hospital in Trenton, under the direction of Dr. Henry Cotton, a well-known psychiatrist. In an extreme and somewhat twisted version of Mechnikov’s theory of intestinal health as integral to overall health, Cotton held that insanity was fundamentally a toxic disorder resulting from chronic infections in the intestines and other parts of the body. His “cure” for the insanity was the surgical removal of parts of the body believed to be infected—including teeth, tonsils, sinuses, stomachs, and portions of the intestines.

Although his methods were controversial, Cotton had had exceptional training, was well connected in the world of psychiatry, and held a prestigious post. Moreover, it must be pointed out that from 1915 to 1925, surgery was the standard therapy, in all major hospitals and medical schools throughout the country, for the presumed “chronic infection” that caused mental dysfunction. So as Andrew Scull relates in his riveting 2007 book, Madhouse: A Tragic Tale of Megalomania and Modern Medicine, Cotton wasn’t stopped until it was found that he had falsified data on outcomes.

When the ax fell on Cotton, however, it didn’t fall so much on the procedure as on the whole idea of the gastrointestinal connection to mental illness. In fact, his fall from grace was hard enough to shatter not just his reputation but the entire concept of chronic intestinal infection—dysbiosis. For nearly eighty years, no one dared even discuss gastrointestinal toxicity at any major medical center or meeting out of fear of reprisal from the medical establishment.

Nearly a century later, we understand that the blanket condemnation of Cotton and everything connected with him, while perhaps understandable given the barbarity of his methods, threw out the baby with the bathwater. Indeed, by taking our eye off the connection between gut and brain, the distaste for Cotton may actually have slowed our ability to address the real imbalances in our assimilation-elimination process. Today, we once again recognize and have investigated the association between the intestinal tract and brain function, and we see how very profound it is in its impact on our health. Few connections exemplify that association as clearly as the connection between celiac disease and dementia.

THE GUT-BRAIN CONNECTION: CELIAC DISEASE AND DEMENTIA

You’ve probably heard of celiac disease. It is a really unpleasant disorder in which the lining of the small intestine is damaged by a family of proteins, called gluten, found in cereal grains, and it has long been recognized that a genetic susceptibility to that grain protein is the cause of the disease. Its symptoms, apart from pain and discomfort, may include chronic constipation and bloody diarrhea, fatigue, in children a failure to thrive, autoimmune disease, and a high incidence of dementia.

Traditionally, the dementia was considered a disease adjacency or comorbidity—just a statistical happenstance. But the discoveries that have shown us the links connecting the gut, immune system, and nervous system have changed that story. We now see a cause-and-effect relationship between celiac disease and dementia that starts with the activation of the intestinal immune system and ends with the triggering of brain inflammation. Here’s how it happens.

The gastrointestinal system of a person with the genetic susceptibility to gluten reacts to its presence in food as to a hostile foreigner. That reaction activates inflammatory messenger molecules that travel through the bloodstream from the gastrointestinal immune system to the liver. Ten percent of the cells that make up the liver are called Kupffer cells—after the scientist who first observed them. Kupffer cells are specialized immune cells, and although they reside only in the liver, they are derived from the same lineage of cells as the gastrointestinal immune system cells.

So when the inflammatory messenger molecules from the gut arrive in the liver, they stimulate their relatives, the Kupffer cells, to release messengers from their genes. These messengers in turn activate an inflammatory response in white blood cells that are also part of that same immune cell lineage. These white blood cells then travel to the blood-brain barrier, where they trigger an inflammatory response in cells in the brain called microglial cells, which are—you guessed it—also relatives of the gastrointestinal immune cells, the Kupffer cells in the liver, and the circulating white blood cells. In fact, the microglial cells are the brain’s immune system and, when activated, they produce their own inflammatory messengers.

But these messengers sent from the brain’s immune system constitute an inflammatory response that causes collateral damage to the neurons in the brain. The result? Certain types of brain function—specifically, the functions of memory and cognition—suffer losses, causing the clinical outcome we know as dementia. It is a classic example of the gut connected to the liver, connected to the immune system, connected to the brain. What we understand from it through the lens of our twenty-first-century focus on systems biology is not to treat the brain dysfunction with a drug—and there are numerous medications for doing so—but rather to treat the immune inflammatory response of the gut. Eliminating gluten from the diet to normalize gastrointestinal function is certainly a more sensible first step than throwing more medications at all those physiological messengers.

HOLES IN THE BARRIER

This treatment model—addressing the assimilation-elimination process of the body as a way of treating chronic illnesses that may have their origin there—extends also to the management of other neurological diseases. A number of clinical studies have demonstrated improvement in neurological function in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), who were put on a gluten-free diet plan. A good friend and colleague, neurologist David Perlmutter, in his superb book, Grain Brain, has described his pioneering work in treating various neurological conditions with a gluten-free diet.

The question is how the hostile foreign substances manage to get into the blood from the gut in the first place. Didn’t we say that there’s an intestinal immune system that puts up a barrier prohibiting the absorption of immune-activating substances? Has something somehow been poking holes in the barrier?

The answer is yes, and the term for it is endotoxemia. It means that toxic substances produced in the intestinal tract are indeed leaking through the barrier into the blood. Research gastroenterologists call it “leaky gut syndrome,” and they have confirmed that it primarily occurs after the consumption of foods high in fat and sugar or from ingesting other caustic chemical or food substances. The leaks allow the entry of substances the barrier normally prohibits. These substances spill through into the intestines, where the intestinal immune system sees them as foreigners, takes defensive action, and turns up the dial on the genes that control the production of inflammatory messengers.

But just what is poking holes in the barrier? What is responsible for this loss of integrity in the mucosal barrier? Researchers believe it is exposure to caustic substances—possibly from food allergens, infectious bacteria, viruses or yeast, drugs and alcohol, or harsh chemicals. Whatever the precise cause, this loss of integrity in the barrier that normally prohibits access to the intestinal immune system stirs such diverse chronic symptoms as sinus problems, joint pain, headaches, skin problems like eczema, and anxiety. Just how bad the symptoms get will depend on just how leaky the barrier has become and just how many endotoxins get absorbed into the blood.

WHAT TO DO?

Back in 1990 when I and my close friends and medical colleagues, David Jones, Leo Galland, Sidney Baker, Joseph Pizzorno, Graham Reedy, and J. Alexander Bralley, were first talking about the clinical applications of functional medicine, we all agreed that addressing an imbalance in the assimilation-elimination process would be among the most important.* At my suggestion, we even developed an acronym for the functional medicine approach to what we call gastrointestinal restoration. We named it the Four R Program, and over the subsequent decades, it has been tested, refined, and taught to more than a hundred thousand health practitioners around the world.

The Four Rs stand for:

• Remove

• Replace

• Reinoculate

• Repair

Here’s how it works.

Step One: Remove

Simply put, get rid of all food allergens or food substances producing sensitivities. Start by evaluating the reaction to gluten in grain products; to casein protein in dairy products; and to soy products, citrus products, peanuts, eggs, and shellfish—all classic producers of immune response. Be careful also to reduce exposure to moldy foods and fermented foods.

Step Two: Replace

If the stool contains undigested food materials or fat, that is a telltale sign that the enzymes normally released during the digestive process may not be adequate for proper function. Take a digestive enzyme supplement before meals to improve digestion and absorption. A pancreatin digestive enzyme tablet that can break down protein, carbohydrate, and fats may help in improving assimilation when taken along with meals.

Step Three: Reinoculate

Add a prebiotic and probiotic supplement to the daily regimen. Probiotic organisms of the Bifidobacterium bifidum and Lactobacillus acidophilus strains have been proved to be safe and effective for improving digestive function, but do start slowly with these supplements, and increase the dose over two to three weeks. The ideal daily dose consists of 3 grams per day of the prebiotic and a 2 billion probiotic count. The ideal probiotics dose is considerably higher than one can get in a standard serving of yogurt, so it may be more convenient to take in a therapeutic tablet or powdered delivery form.

Step Four: Repair

Take a supplement of the nutrients that can support the healing of the intestinal mucosal barrier. The most important of these are zinc (15 milligrams), pantothenic acid (vitamin B5, 500 milligrams), omega-3 fish oils (2 to 3 grams), and the amino acids L-glutamine (5 grams) and magnesium (200 milligrams), along with a B-complex nutritional supplement.

Let’s be clear: The Four R Program isn’t for the odd stomach upset; nor is it a maintenance program. It addresses a fundamental imbalance in the core physiological process of assimilation-elimination. For a researcher like myself, nothing brings me up short quite as abruptly or quite as formidably as getting the opportunity to understand what this means in personal terms, as happened to me some years ago in Denmark.

I was there to deliver a lecture at the Copenhagen Hospital and Medical School about the gastrointestinal restoration program. After the lecture, a woman approached me, introduced herself as Ilsa G., the head surgical nurse in the hospital’s gastroenterology department, and began to tell me about her daughter—I’ll call her Margret. By the age of fifteen, Margret had a history of inflammatory bowel disease that had left her malnourished and slow to develop. She had undergone several surgeries for the condition, but her health was so uncertain that she could not leave the house or attend school. Instead, she was tutored at home, where she lived a limited, isolated life.

Ilsa somehow heard about the Four R Program and wondered if it might be worth trying with Margret. She asked her boss, head of gastroenterology at the hospital, what he thought. He hadn’t heard anything about it, but he thought it sounded “strange” and didn’t recommend it because Margret’s condition was, as he put it, so “unstable.”

It was at this point in the conversation that something happened that for me was transformative. Ilsa turned to a statuesque young woman standing just a bit behind her and introduced her as Margret, now eighteen. Despite what her boss “recommended,” Ilsa had decided to implement the Four R Program for Margret. From the start, the intestinal flares subsided and Margret was able to eat. She gained weight, grew seven inches, and had her first menstrual period. During the second year of the program, Margret was able to withdraw from all the multiple medications she had taken for years. Now, said Ilsa, “as you can see, the results speak for themselves.”

But Margret had something to say as well. In superb English, she told me that for her, most important was the trip she had taken the previous summer—she and a bunch of friends, traveling around Europe, backpacks on their backs, wandering wherever the fancy took them—and, said Margret, “I had no problems.

“Thank you,” she added, “for your program that saved my life.”

I don’t know if you can imagine how it feels to hear something like that. My only rather feeble response was to thank her for sharing her story and to wish her the best in her life.

Sometimes, we scientists need reminding that the end result of our research is the real lives of real people.

So, yes, the core process of assimilation-elimination can be central to the health of the entire human organism. Co-equal in importance is our process of detoxification, without which we would be in a constant state of toxicity while our health and our longevity would be in perpetual jeopardy.

CHAPTER 4 TAKEAWAY

1. The digestive system is also the center of the immune system.

2. The digestive system, nervous system, immune system, and hormone-producing endocrine system all function together in an interconnected way.

3. Nutritional deficiency can result from poor digestion or ineffective or incomplete assimilation of nutrients.

4. The digestive system is inhabited by several hundred different species of bacteria and microbiota that influence health and disease patterns.

5. Specific foods affect the secretion of substances from the digestive system and in so doing can influence the risk of various chronic diseases.

6. The Four R Program represents a clinically proven approach to managing complex health problems associated with imbalances of the assimilation-elimination process.