Vegetables discussed in Chapter 9

CHAPTER

9

What to grow . and how to grow it

This chapter provides growing details, vegetable by vegetable. It is not organized A to Z. Instead, the vegetables are listed in an order based on their importance to a self-sufficient homestead economy and their difficulty to grow.That’s why kale and potatoes (both Irish and sweet) come at the beginning and celery comes at the end. I am only going to provide the essentials and leave it to experience to reveal the rest to you. I will assume you have understood what I said in previous chapters. If you find yourself puzzled by anything that follows, I suggest you do a bit of rereading.

Sowing depth. Tiny seeds like celery, basil, sorrel, and most of the herbs should fall into tiny cracks and crevasses of newly raked soil, to be barely covered (if at all) with a sprinkling of fine compost. Then press the earth down gently either with your hand or the back of a spade, much as you would roll a large area like a lawn. This essential step restores capillarity. Fine seeds can only be directly seeded outdoors in mild temperatures, or the rows must be shaded temporarily until they sprout. Ordinary small seeds the size of bras-sica, carrot, parsley, and fennel are sown about half an inch (1.25 centimeters) deep. Larger “small” seeds like spinach, beet, chard, radish, and okra are sown about three quarters of an inch (two centimeters) deep. Large seeds like the legumes, corn, and cucurbits are usually planted to a depth of about four times their largest dimension.

Vegetables discussed in Chapter 9

Fertility needs. I assume that you understood the three levels of soil fertility I set out in Chapter 2, where I described the idea of low-, medium-, and high-demand vegetables and showed you how to create minimum levels of soil fertility to grow them. Don’t forget that these are minimums; all vegetables grow much better when given soil more fertile than the bare minimum.

Plant spacing. I will not be repeating the information on spacing provided in Figure 6.1. I suggest you flag that page or make a photocopy of it for rapid access. In this chapter, I’ll refer to various spacing arrangements in shorthand.

The term “on stations” is British. It means that a few seeds are sown in a cluster, usually on raised beds or wide raised rows. The clusters are at fixed distances, such as 24 by 24 inches (60 by 60 centimeters), and each cluster is thinned progressively. Sowing seeds “in drills” means they are set in the bottom of a furrow. Sometimes seeds are to be sown in highly fertile hills. These hills can be made in a raised bed on stations, sometimes not.

Progressive thinning. I will frequently suggest that you thin to a single plant, progressively.Here’s how it works. Suppose you’re growing looseleaf lettuce and the mature heads will need to be 12 inches (30 centimeters) apart. First sprinkle seeds thinly in drills. Ideally, if you get excellent germination, you will have about one seedling emerging every inch (2.5 centimeters). However, distribution this uniform doesn’t happen unless you’re a farmer using precision planting equipment and sowing the highest-quality seed of predetermined sprouting ability. In the home garden, clumps of seedlings inevitably emerge in places, so immediately after emergence you should reduce severe competition: thin any seedling clusters so the survivors don’t quite touch. When this initial plant density starts to compete for light (the seedlings will lean away from each other) thin them again so they don’t quite touch. A week or ten days later, when they are again bumping, take out every other plant. Suppose at this point they are three inches (eight centimeters) apart. When these are touching, remove every other plant. Now they’re six inches (16 centimeters) apart.When these plants are touching, cut off every other one again. Thinnings of this size are definitely salad material. And now the survivors in that row are properly spaced to reach maturity.

Seedling clusters on stations can also be thinned progressively. Start with three to five seedlings and gradually reduce their number so that by the time the best plant has a few true leaves and is securely established, it stands alone on that station.

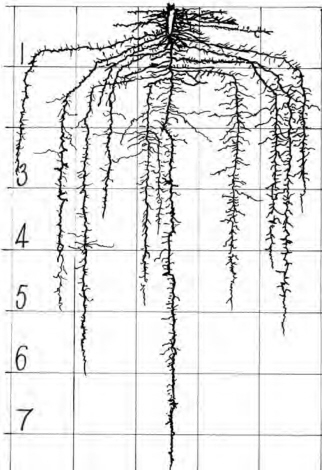

Root system drawings. Muriel Chen, my wife, copied the drawings of root systems in this chapter from Weaver’s classic study Root Development of Vegetable Crops (RDVC). They are included to help you realize that the plant growth you can’t see is as important as what you can see. Each drawing’s scale is one foot per square. Keep in mind that Weaver worked in a rather dry climate on deep open soil that posed little opposition to full root development.

In more humid climates, most soils divide into layers called topsoil and subsoil. The subsoil is typically clayey and won’t allow such full expression of root development — but you can be assured that the roots are trying to develop further, nonetheless.

Weaver’s drawings, combined with an understanding of how roots work, will help you garden better. Almost every plant tries to control the soil below it. To do that it secretes chemicals that repel the roots of other species. Some of these chemicals are so effective (and long-lasting) that a year after one crop is grown in a spot, another species may do poorly because these root exudates are still present.

Also, notice in Weaver’s pictures that roots never turn back and grow toward the center. The plant tries to penetrate new soil for untapped sources of moisture and nutrition; it would be a waste to make a denser root system than necessary.How do plants “know”? Again, it is root exudates — chemical signals stop its roots from growing near its own already-established roots.

Finally, and this fact may be the single most important thing you’ll ever grasp about growing plants, for a plant to acquire nutrition efficiently, it must have an ever-expanding root system. A root extends only from its tip, and it is capable of efficiently assimilating moisture and nutrients for only a fraction of an inch behind the tip.That’s because a few days after it is formed, what was the root tip becomes covered by a kind of bark that reduces penetration of moisture. It is only by creating new root tips in an ever-increasing and ever-expanding network that the plant can feed efficiently. But the plant can’t readily make new root tips in areas it has already filled with roots. And because of exudate warfare, it can’t make them effectively in areas that another plant has already filled with roots. My point is that when root systems begin to compete, the plants are not as able to acquire nutrients. This is a stress to them, and they may show it in various ways: their growth will slow, they will be more easily attacked by insects; they will stop producing as much new fruit; they will be more susceptible to diseases.They can be starving in the midst of plenty.

My previous gardening books were written for Cascadia. I probably know its every district, microclimate, and soil type. I am learning Tasmania’s nooks and crannies. But no person can intimately grasp all the regions of North America, much less the rest of the English-speaking world. So in this section I usually won’t be able to tell you three things: (1) precise planting dates for your location; (2) the most suitable varieties for your district; and (3) the handling of some pest or disease problem either unknown to me or unique to your area.These kinds of data are best obtained from a governmental agricultural advising service.You’re paying the taxes to support it; make use of it, and give those civil servants a reason to draw their salaries. I hope that the third point will be an infrequent event if you take my advice about making plants healthy by making soil fertile and by not asking a plant to handle seasons or soil conditions it is not bred for.

Crops that are easiest to grow

In this section I cover vegetables that are generally trouble-free and low- to medium-demand in terms of soil fertility needs.To keep the size (and cost) of this book lower, I discuss a few harder-to-grow relatives along with an easier one. New gardeners should not bet the ranch on more-demanding veggies than the ones in this section.

Kale, collards, and giant kohlrabi

There are two kale species. One is a Brassica oleracea. I’m not going to be routinely tossing Latin names around in this chapter, but in the case of the brassica family the distinction is useful because the other kale species, Brassica napa (it includes rutabagas), grows in an entirely different manner.The B. napa kale is usually called Siberian. B. oleracea grows an unbranched tall central stalk. Siberian forms a rosette pattern, meaning that all the leaves come out of a central point close to the ground, similar to a lettuce or spinach plant. Some prefer Siberian’s flavor when kale is used raw in salads.

Kale of either sort is the most vigorous and most cold-hardy of all garden brassicas. It will produce when other coles fail. Collards are a non-heading cabbage only slightly less vigorous than kale and may be grown just like kale. Giant kohlrabi is basically a low-demand fodder crop whose tasty globe can grow to the size of a volleyball.

All coles need more calcium than most other vegetable species. If you’re not using COF and if you are gardening on rain-leached land (where there is enough rainfall to grow a lush native forest), then before sowing any brassica crop you should broadcast and work in five pounds (about a quart or 2.25 kilograms/ one liter) of finely ground agricultural lime per 100 square feet (ten square meters) of growing area. Do not spread more lime than that without a soil test.

I have seen kale resume growing after thawing out from an overnight low of 6°F (–14°C). As long as the soil has not frozen, kale will keep going. So will endive, spinach, and a few other minor salad veggies. Having fresh salad greens throughout the winter will certainly appeal to any gardener living where the snow lies thickly. I refer those living where the soil freezes in winter to Eliot Coleman’s book The Four-Season Harvest, listed in the Bibliography.

Growing details. Kale’s flavor gets sweeter after some frost in the same way the chicories do. Collards don’t need chilling to be good eating, which is probably why they are more popular in the American South. I enjoy seeing huge frilly plants by autumn, so I start kale about three months before the first frost on 24- by 30-inch (60- by 75-centimeter) stations. I once grew giant kale by direct-seeding it in spring on four-foot (120-centimeter) centers and initially making their soil as fertile as possible. Each one reached four feet in diameter and 4½ feet (140 centimeters) high by frost. Had I given them any water at all that summer they probably would have become as tall as I am.

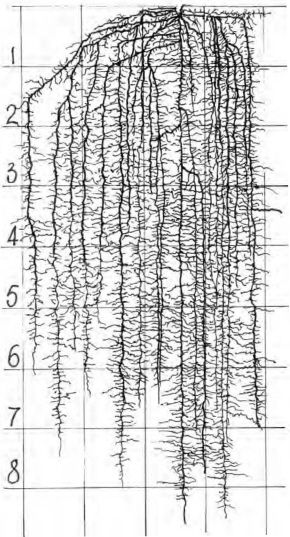

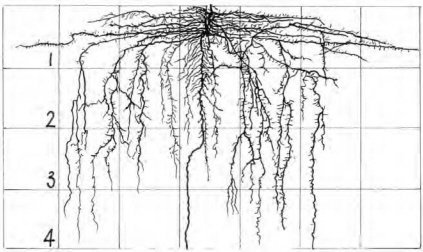

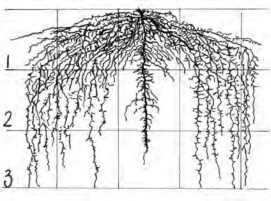

Figure 9.1: This kohlrabi was sown in spring; the drawing is made after 120 days of growth. Clearly this is a vegetable capable of foraging. Kale’s root development is not very different. (Figure 40a in RDVC)

As a hasty fill-in crop started six weeks before the first frosts, kale will make a small plant and in this circumstance should be sown in drills about 12 inches (30 centimeters) apart and thinned progressively.Whether it’s huge or modest, it’ll be equally frost-hardy. No extra fertility should be needed for late sowings as the kale will make use of what is left from the previous crop.

I start giant kohlrabi just after the solstice for harvest as an autumn and winter crop. It is grown as if it were a medium-sized cabbage. Although it will produce at fertility levels suitable to a field crop, giant kohlrabi will definitely respond to better soil and abundant soil moisture by becoming larger, more mildly flavored, and more tender.

Pests and diseases. I always am pleased to see that cabbage worms do not have any interest in my kale. If they did I would spray Bt. Kohlrabi is only slightly more interesting to them. Perhaps this disinterest is because the moths are diverted to the more refined brassicas in my garden — which serve as a trap crop and certainly do require regular spraying with Bt.

Growing refined brassicas. If you can grow a large kale plant, then you have also mastered the art of growing the weaker,more inbred, large brassicas; all were bred from the same wild Brassica oleracea that kale came from. Imagine a head of cabbage as a non-curly kale whose stalk has become so shortened that it has next to no space between leaves and that overemphasizes kale’s tendency to wrap its leaves at the growing point.The Brussels sprout is but a kale that makes little cabbages at each leaf joint. For broccoli and cauliflower, imagine a slightly less aggressive (and less cold-hardy) wild oleracea strain that naturally made larger flowers; now it is bred to make enormous flowers. As you move up the scale of refinement from kale to cabbage to Brussels sprouts to broccoli to cauliflower, each requires more fertile and more open soil and even more moisture than the previous one.

One last comment on refinement: the cabbage is intrinsically a large vigorous plant that makes a hefty head.However, to create little heads currently popular with the supermarket trade, cabbage has to be highly inbred and weakened.These small-framed varieties are touchy little critters with delicate root systems intolerant of dry or compacted soils. They need to be coddled. New gardeners will do better to grow bigger ones.

All brassicas may be directly seeded exactly as I suggest for growing kale. It is best to make small hills in raised beds for the refined brassicas, concentrating an extra half cup (120 milliliters) of COF or an extra large double handful of strong compost immediately under their stations. Two points about cauliflower: it has a particularly weak root system that doesn’t thrive in clayey soils. It also does not like maturing in heat, making spring cauli sowings a bit chancy because of the unpredictable onset of hot weather.A few broccoli varieties may handle hot weather better; the catalog will proudly state this. The safest thing is to schedule cauliflower for autumn harvest. In the mild-winter climates, refined brassicas may be started after the heat of summer lessens for autumn and winter harvest and, by using the right varieties, for overwintering and spring harvest.

Figure 9.2: The root system of a large-framed midseason cabbage after growing about 100 days from direct seeding. The leaves have not yet wrapped into a head. Harvest will be in another four to five weeks. At harvest the root system of this plant will thickly fill the soil to a depth of five feet (150 centimeters) but will not become more extensive. Kale makes a more extensive and deeper root system than this. (Figure 29 in RDVC)

Varieties.Winterbor (hybrid) is the most frequently offered oleracea type because it is more vigorous and perfectly uniform. Open-pollinated (OP) kale is vigorous too, so the old OPs will serve fine. At the time of writing, though, when it comes to refined brassicas there are no productive OP Brussels sprouts left except in Chase’s catalog (see Chapter 5).

Harvest, storage, and use. With kale, if you do not pluck the growing point at the top of the stalk, the production of new leaves will continue. If olracea-type plants overwinter, in early spring they will begin making numerous small (more tender and more delicious) leaves all along the thick woody stalk. (You’ll think of Brussels sprout when you see them.) Collards are often sown in drills with the intention of eating the progressive thinnings. Kale can be used this way, too. Kohlrabi will await harvest through rather severe frosts; where the ground freezes it will store well in the root cellar.

Kale and collards are mainly used as pot greens.To encourage those unfamiliar with eating them, may I recommend a simple and (naturally) frugal Scottish recipe called colcannon. Fill a large pot with finely chopped kale, add a quarter inch (six millimeters) of water, and set the heat at low. As soon as the leaves collapse, add an inch-thick (2.5-centimeter) layer of roughly cut up, unpeeled potatoes and allow the whole thing to steam until the potatoes are soft enough to mash. Then mash everything. Do not pour off any remaining water. Mash the lot and retain the minerals. Add your usual mashed-potato seasonings. Steamed kale by itself is a bit intense.And potatoes by themselves are usually a bit low in protein and minerals. Combined they make near-perfect nutrition with complementary flavors.

Finely shredded in moderate quantities, kale (especially Siberian) blends well into greens salads. Kohlrabi is tasty when coarsely grated and made into slaw-type salads as though it were cabbage. I like dipping raw kohlrabi chunks.

Saving seed. All Brassica olracea cross-pollinate; bees do this task. Crosses are unlikely to make desirable plants. Isolating different sorts by a half mile (800 meters) may do for low-quality seed. Siberian kale, also bee-pollinated, crosses only with rutabaga (swede) and has the same relationship to the rutabaga as Swiss chard (silverbeet) has to beet (beetroot) — it is a rutabaga bred for tasty leaves instead of a bulbous, flavorsome root. Otherwise, Siberian makes seed like any other brassica.

These brassicas are biennial, meaning they must pass through a season of cold weather and short daylength before flowering is triggered in spring. To overwinter large kale plants with thick woody stalks where the soil freezes, dig them up carefully in late autumn so as to preserve much of their root system, replant them in a bed of damp soil in a root cellar, and let them rest there until spring, when they are transplanted back outside. They might survive a not-too-severe winter if buried under enough soil and then exposed again in spring; cabbage seed is made this way in Denmark. In milder locations they survive winter unprotected.

The blooming plant makes huge floral sprays. Each of the thousands of small yellow flowers makes a thin pointed pod that holds a few round black seeds.The earliest time you should harvest is when some of the earliest ripening pods have shattered (released seed) and most of the rest contain ripe or nearly ripe seed (the seed is fully ripe when it has turned dark brown or black). Pull the plants, roots and all, shake off as much soil as possible from the roots, and spread them on top of a (big) tarp in the shade under cover, where there is good airflow, to dry slowly and finish ripening. Then on a bright warm day of late summer, drag the tarp into the sun and let the whole lot of straw dry to a crisp. Late that afternoon do some marching in place atop the straw, releasing most of the seed from most of the pods. Lift off the strawy bits and put them in the heap of dry vegetation awaiting your next compost pile. Left on the tarp will be seed, broken seed pods, and some smaller trash. Put it all in a large bucket and then, in a light breeze, slowly pour the contents of one bucket into another.Hold the top bucket a few feet above the bottom one so the breeze may blow away the light stuff while the seed falls into the lower bucket. This process is called winnowing. You may have to pour from bucket to bucket numerous times before you have relatively pure seed free of chaff. (It can help to screen out the larger bits of chaff before winnowing; use any sort of improvised sieve.) Do not be concerned if you lose up to a third of the seed due to wind blowing it beyond the bucket waiting to receive it. This is the lightweight unripe stuff that will have poor storage life and low germination — the seedroom floor sweepings.

Do not attempt to save either sort of kale seed unless you have at least six plants involved in sharing pollen. If you work from too small a plant population, you’ll experience a rapid onset of inbreeding vigor depression. Kale or collards are the only large brassicas the home gardener should ever attempt to grow seed for. I would not advise growing seed for the refined large brassicas unless you have at least 50 plants in the gene pool — 200 is better. But with kale, involving such a small number of plants is okay because kale still retains most of the vigor of wild cabbage; even if some of that vigor is lost, it’ll still grow okay.

Potatoes (Irish)

Introduced to Europe after the Incan conquest, the potato languished for around two centuries. Because these initial varieties were adapted to tropical daylengths, the potato was considered a low-yielding curiosity. Eventually, better varieties were bred. Then the potato caused a European social revolution because it produces many times more actual nutrition per acre than any other staple crop except perhaps paddy rice. The potato allowed a cottager with less than an acre to feed a family. So Europe’s population increased rapidly. This is one reason there were so many European peasants coming to the United States after the War Between the States.

Potatoes need not be merely starch.They can contain up to about 11 percent protein, matching the protein content of human breast milk.The quality of nutrition you end up with has a lot to do with both variety and the pattern of soil fertility. If you’re growing a starchy variety, which is flaky and crumbly (and often called a “chipper” because it is the starch that browns nicely when making potato chips), and if you are growing your spuds with lots of moisture and fertilizing your soil so that it offers the plant excesses of potassium, then you’ll end up with a much bulkier harvest of low-protein spuds. If you grow a “boiling variety,” which is often yellow-fleshed with a waxy structure that doesn’t fall apart when boiled, if you reduce or avoid irrigating once tuber formation begins, and if you build your soil’s fertility so that it has considerable mineral nutrients but a rather low level of potassium, you’ll end up with a somewhat smaller bulk yield of somewhat smaller-sized spuds that have considerably more taste and nutrition.

To achieve nearly complete food self-sufficiency using European cereal grains, a family needs more than an acre and will almost have to use draft animals (which will need food grown for them, too, requiring working even more land than the first acre) or a husky rotary cultivator. If the staples are the Native American ones — corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers — an acre garden that can be worked entirely by hand labor will serve an extended family. But if the staff of life is the lowly spud, far less land than that will serve, considering that potato yields generally exceed 300 bushels per acre (10,000 kilograms per hectare).

Growing details. The “Irish” potato is grown much the same way in all variations of temperate climates. The vines are not frost-hardy, so it must be planted late enough in spring to emerge after the last frost. Frost is not a complete risk; if the young vines are burned by frost, more will emerge. But the loss of the first bit of leaf will reduce the ultimate yield, so it’s best to avoid it. In mild-winter (frost-free) regions it is possible to sow late in summer and grow spuds as a cool-season crop, but this practice results in low productivity. That’s because the tuber is a savings account of surplus sugar made by the leaves, and when intensity of sunlight drops off markedly after midsummer, so too does sugar formation decline. Despite the low yields, winter spuds are grown in frostless Florida because of the high prices obtained for new potatoes in the north during late winter and early spring.

Root cellaring

To maintain a body in robust health you must feed it a sizeable amount of fresh food, preferably raw. The nutritional quality of canned and frozen foods has been massively reduced. The same is almost as true of dried foods, especially if they were blanched during processing. Fortunately, in cold-winter regions it is possible to store fresh vegetables and fruit in living condition for many months without using any energy to do so. This is accomplished by cellaring. Imagine having the makings for a fresh leafy green salad in the cellar throughout the winter; eating bins of root vegetables, your own cabbages, and perhaps Brussels sprouts (still on the stalk) in midwinter; or sprouting your own Belgian endive and not considering it an expensive delicacy.

Few North American homes are still equipped for root cellaring because most of them have the furnace in the basement. However, it may be possible to wall off and highly insulate a part of the basement for use as a winter food-storage cellar. Otherwise you can dig a cellar outside, though this may be less accessible during the time of heavy snows. Making a root cellar is not generally regulated by building codes and requires no permits nor adherence to any prescribed construction techniques (other than the requirement that it not collapse while you are inside it). Cellars may be made of recycled materials. Even old chest freezers may be recycled into small root-storage compartments.

The basic technique behind cellaring is to rapidly lower the temperature to a few degrees above freezing and then hold it there, steadily, through the winter. During autumn you open air vents at night and close them during the day. During winter, less ventilation is needed because, above all, the cellar must not go below freezing. The more stable the temperature, the better the food in the cellar will keep.

Using the term “root cellar” shows the limited application most Americans made of this procedure. The Europeans have demonstrated far more ingenuity and wouldn’t dream of putting only root

crops and apples in storage for wintertime. Basically, roots are put in slatted boxes on shelves or, if the vegetable has a tendency to dry out (like carrots or beets), are packed in damp coarse sand and housed in barrels (or large trash bins). Leafy crops like cabbages and heads of endive and escarole, which blanch during storage, becoming milder and more tender, may also be kept over winter. Immediately before it gets too cold for them outside, which is after some frosts but before hard freezing begins, dig them up, shake the earth from their roots (sometimes you need to break off the large outer leaves), and then transplant them into the cellar and put their roots into shallow beds of soft moist soil. There is no reason why such earth beds could not be constructed on a concrete slab, although traditionally the floors of such cellars were bare earth.

The only way people in snow country can make seed for most biennial crops is to cellar them over winter and then plant them back outside in spring. This was done extensively on a home-garden scale (and commercially to a lesser extent) in the United States before the West Coast seed industry developed.

Root Cellaring, by Mike and Nancy Bubel, is an excellent book about cellaring that is worthy of the most profound consideration.

I mention cellaring for those of my readers who may need to make use of it. However, since being an adult I have lived in climates where the technique is not applicable. In California, where I first learned to garden, veggies grew lushly 12 months a year. In Oregon, a well-insulated, unheated outbuilding was plenty good enough for spuds and apples, while carrots and other root crops would overwinter in their growing beds with only a bit of soil put atop them to protect their crowns from a chance shallow freeze. And greens! Green salads grew right through the frosts and even emerged from the occasional quick-melting snows to grow some more. Ah Cascadia! Closest thing to paradise there is in North America.

“Seed” consists of chunks cut from large potatoes or whole small ones. Vines emerge from the eyes. The ideal seed is termed a “single drop,” a small uncut potato weighing about two ounces (60 grams) and having at least two eyes. Each chunk cut from larger potatoes must also have at least two eyes and weigh at least two ounces.

Farmers, using machinery,must plant unsprouted seed pieces because any sprouts would be knocked off by rough handling. So farmers usually treat the cut surfaces of their seed-potato chunks with fungicides because they’ll be in the earth and subject to rotting for some time before the eyes start growing. Home gardeners can do much better.We can chit our seed and then handle already sprouting seed gently enough that the shoots aren’t damaged. Chitted seed is already growing when it is planted.

About six weeks before planting, spread uncut seed potatoes on a tray in a brightly lit room that is not too well heated. I put mine on cookie sheets in front of a window that gets no direct sunlight in order to avoid drying out my seed. By planting time the potatoes will have turned light green, and shoots will be emerging from many of the eyes. On planting day I cut the larger potatoes in chunks; I try to make sure each chunk contain two eyes that are actually sprouting.

A day or two before planting, dig the rows.One row of potatoes can make luxurious and extraordinarily high-yielding use of an entire four-foot-wide (120-centimeter) raised bed when planted longways down the center, but if you’re growing more than one row, it’s best to plant spuds on flat ground, making their long rows about 36 inches apart on center (90 centimeters). Spread compost or well-rotted manure atop multiple rows in one-foot-wide (30-centimeter) bands, a quarter to a half inch (6 to 12 millimeters) thick, and then deeply dig the compost-covered rows (not the spaces between the rows).Try to loosen the earth well. If you want the highest possible production and aren’t growing a huge plot, excavate the rows first, before improving their fertility. Remove soil one shovel blade wide nearly to the depth of a shovel, set it beside the ditch you’re creating, put fertilizer and/or strong compost into the ditch, and then, standing in the ditch, dig it in as deeply as another full shovel’s length. That’ll put the fertility well below the seed piece, where the main root system will form.

I do it this way: I spread four to six quarts (four to six liters) of a lime-free complete organic fertilizer per 50 row feet (15 meters) into that shallow ditch and dig it in well.Then I spread a dusting of well-rotted manure or compost over the soil that was removed from the trench and push it all back into the ditch. I end up with a low mound above a zone of loose, humusy soil about a foot (30 centimeters) wide and a foot deep. Below that is another zone of highly fertile soil. If I am really shooting for the highest possible yield, and if I have the free time and energy, after the seed has been planted but before it starts putting roots out I will spade up the earth between the rows.

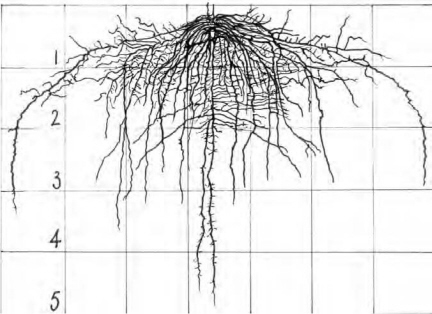

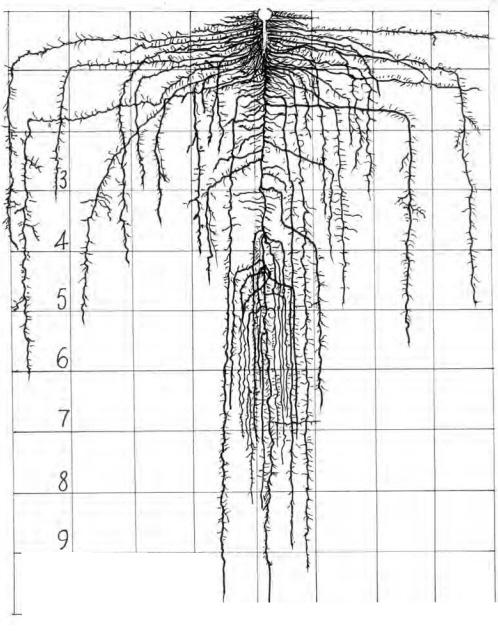

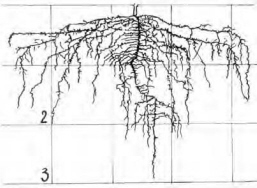

Figure 9.3: A potato plant that enjoyed good soil moisture in deep open loam, shown at the point of beginning to form tubers. The spacing that produced these roots was 14 inches (35 centimeters) apart in rows three feet (90 centimeters) apart, which ideally allows each plant to be nearly the sole occupant of its own root zone. (Figure 40 in RDVC)

To plant sprouting potatoes, pull back the soil from a spot in the center of the row with your hand, opening a small hole about four inches (10 centimeters) deep. Gently set the seed in. If there are long shoots, point them up. Then cover it up. Space the seed pieces 8 to 12 inches (20 to 30 centimeters) apart.Wider spacing will give you more lunkers (huge specimens), a slightly lower yield, and a better ability to handle dry soil. Closer spacing will give you moderately sized potatoes, the largest possible yield, and less ability to handle dry spells.

Farmers must plant their seeds deeply in loose soil and let them grow, accepting that a portion of the spuds forming at the surface will green up and be inedible. When potatoes are grown this way, the soil tends to settle and become compact, reducing tuber formation. Gardeners can do better; we can plant our seed shallowly and then hill up our plants as they grow, thus providing a looser medium for the potatoes to form in.We end up with a higher yield of smoother spuds, while at the same time thoroughly eliminating weeds. Keep in mind that all potatoes will form above the seed piece and that if you do as I am suggesting, the seed will have been placed only a few inches below the original soil line, so your crop will be easier to dig.

A few weeks after planting, the vines appear, emerging more quickly than they would if you had put the seed deeper because the soil near the surface is warmer in spring. After the vines have grown about four inches (10 centimeters), start hilling them up. Using an ordinary hoe, walk beside one row and, reaching over it with the hoe, scrape up a bit of soil from between it and the next row and pull that loose soil (and any weeds you cut off with your super-sharp hoe) up against the vines. Bury the bottom inch (2.5 centimeters) of the vine.Do that from both sides of the row. Five to seven days later the vines will have grown another few inches.Hill them up another inch or two.Never cover more than a quarter of the new growth. By the time the vines are blooming, you should have formed an 18-inch-wide (45-centimeter) mound of loose earth about ten inches (25 centimeters) tall with the vines emerging from the center. It is in this mound that almost all the potatoes will form. From this time, continue hilling up in small increments as weeds emerge between the rows. Do this until the vines start falling over, after which further hilling is not possible.

If you hilled enough, there will be no potatoes forming that are exposed to the light, so there will be no green potatoes to throw away. From this point on, hand-pull any weeds appearing among the vines. There should be next to none. If the crop has grown well it should be nearly impossible to walk between rows on three-foot (90 centimeter) centers without damaging the vines. From this point, it is best to keep your soil-compacting feet out of the plot anyway.

Pests and diseases. All this hilling gives you a good opportunity to check for and control potato beetles if you’re in the eastern United States.

Every expert says not to lime potatoes because it causes scab. I have not noticed any difference, lime or not, but I am providing the obligatory warning here. I usually remember to keep the lime out of the bucket of COF I use to fertilize my potatoes.

There are numerous soil diseases that affect potatoes. It is a good idea to grow spuds on a new piece of ground that hasn’t seen them nor any other solanums (tomatoes, peppers, eggplant) for at least three years.

Varieties. I can’t predict the best varieties for your locality.However, I can tell you that there are early, midseason, and late-maturing ones.To understand how this is, you need to know how the vine works. First the plant grows leaves.

All surplus food made by these leaves is used to make more leaves. Then the plant begins to bloom; at this point, tubers appear as little below-ground nodules along the stems immediately above the seed piece. The nodules begin to fatten into potatoes. At this stage, growth of new leaves slows. A few weeks later, blooming stops.When flowering ceases, production of new tubers, new vines, and new leaves also ceases. The existing leaves pump out sugar and other nutrients that are translocated into the already formed tubers and stored there. This goes on until the vine dies off. As it shrivels, all the nutrients the vine contains are also translocated into the maturing tubers. At this time the potato skins toughen up as they prepare to endure winter.

Early varieties grow for less time before beginning to bloom. They make fewer leaves on shorter vines and thus are done sooner. They also yield less. Late varieties grow on longer before the bloom starts, and they bloom for a longer period. Lates yield more. In climates where there is a long growing season, it is often wise to use the latest of late varieties for the main storage crop, or even to delay planting the main crop for a month after the earlies are sown, because if the main crop vines die back just before the frosts come, their potatoes will have less tendency to resprout prematurely. When lates are finally dug, the weather will have become cool, leading to much longer storage. I always grow a small patch of early potatoes for summer use, but most of the crop will be late varieties.

Potatoes don’t like scorchingly hot weather, especially when it is also humid. For that reason, they are usually grown as a spring crop where summers are long, hot and humid, and are dug early.

Harvest and storage. As soon as the earliest sowing of the earliest variety is in bloom, you can dig a plant for new potatoes. They’ll grow one size every few days as you dig your way down the row. Some people try to gently tickle out the odd new potato without damaging growing plants, but I find this usually causes more loss than it is worth. I just dig an entire plant whenever I need new potatoes.

Do the main harvest when the vines have browned off, indicating that the skins are tough and won’t rub off easily.Dig carefully so as not to cut potatoes. Cuts do not heal well enough for long storage; any cut potato must be eaten within weeks. Do not bruise the potatoes; handle them gently at all times. Using virus-certified seed, I harvest about 25 pounds (11 kilograms) of potatoes for every pound (0.5 kilogram) of seed sown.My yield would be half that with diseased seed.Maybe even less.

Ideal storage conditions are quite humid and a stable 40°F (4°C). Colder than that and the spuds become sweet as the starch converts to sugar. If the temperature goes below freezing, potatoes will be ruined.Warmer than 40°F increases their tendency to resprout. I recommend you study Mike and Nancy Bubels’ Root Cellaring for suggestions of less-formal ways to store things over the winter than in a cellar. I live in a maritime climate and put my spuds in large cardboard boxes that are stacked in a tightly built, unheated outbuilding. I cover the boxes with a few old woollen blankets to make sure no light gets in and also to stabilize the temperature. Given this small attention, they last about five months before sprouting starts, and even then they are quite useable for another five or six weeks if I rub off the sprouts, by which time the first new potatoes are on the horizon.

Saving seed. Don’t save seed unless you absolutely have no choice. The odd aphid passing through infects the vines with assorted virus diseases.These do not kill the plant, but they do reduce its vitality and lower yield — a lot. There are over 20 such diseases and they are transmitted from year to year in the seed itself.The more years gardeners plant from their own seeds, the more viruses the potatoes will contain and the lower their yield will become. It is possible to harvest more than double the yield by sowing seeds certified to be disease free. Such seed is not costly compared to the result it provides.

If you do save your own small spuds to plant the next year, do not do this for more than one or two years before starting anew with certified seed. And do not try to use supermarket potatoes for seed, both because they are not certified and also because, unless they are genuinely organically grown, they have been treated with anti-sprouting chemicals (which gives me yet another reason, beyond their lousy flavor, not to eat commercial spuds). Seed certified as disease-free begins with tissue-culture, laboratory-grown mini-tubers that is grown for a few generations in high-elevation or chilly, isolated places free of aphids. This has nothing to do with being certified as organically grown.

Sweet potatoes

Growing details. Loamy to sandy soils are essential for really good results. It is nearly impossible to lighten up a clay soil enough to grow the finest sweet potatoes because too much manure or compost will cause the quality of the potatoes to suffer.

The root system sprawls to match the vines, so spread a quarter- to a half-inch-thick (6- to 12-millimeter) layer of well-rotted manure or finished compost over their entire growing area, then dig the entire area. Sweet potatoes also grow well if you dig in a thick stand of an overwintered legume green manure. Form wide raised rows four feet (120 centimeters) apart on center. Because good drainage after heavy rains is essential, raise their beds about six to eight inches (15 to 20 centimeters) above narrow footpaths between them. Once their beds are formed, set either vine cuttings or rooted shoots 15 inches (40 centimeters) apart atop these ridges.They may also be arranged with three seedlings planted in a moderately fertile hill, the hills on four-foot (120-centimeter) centers.

In the right soil type, given only moderate fertility, and grown where summers are long and nights are warm, each plant can produce 8 to 12 good-sized potatoes.When grown in the northern United States, the yield may drop to as low as about one pound (450 grams) per row foot (30 centimeters).You can save planting stock from the previous year’s crop or buy ready-to-plant shoots. If the seedling raiser is reputable, buying may be the best option because sweet potatoes accumulate virus diseases like Irish potatoes do. They also have a tendency to mutate. Commercially raised shoots or seedling are usually only a few generations away from pure, virus-free tissue-culture clones. Statistics show that virus-free starts increase yields by as much as a third.

To start only a few vines, in a warm place suspend a sweet potato on toothpicks in a container and cover half of it with water. You can grow larger quantities by placing several presprouted (or conditioned) sweet potatoes on a bed of sand, covering them with a two-inch (five-centimeter) layer of moist sandy soil, and keeping that soil between 70°F and 75°F (21°C to 24°C). Presprouting (what is called “conditioning” in the commercial trade) consists of holding the roots at about 85°F (29°C) and high humidity for a few weeks until shoots start to develop. You can easily accomplish this at home by putting a few roots into a germination box (for heat) that also holds a large open pan of water (for humidity). Don’t allow the presprouting chamber to become so humid that the roots are actually wet; this may cause mold or fungus to form on them.

In the deep south of the United States, outdoor nursery beds are used. The soil will naturally be at the right temperature to sprout the roots about a month to six weeks before the correct time to set the shoots out. The time to start the nursery is when the night temperature stops falling below 60°F (15.5°C). If you’re farther from the equator, you may have to bed the roots in a greenhouse or indoors, putting a soil- or sand-filled box in a bright sunny window in a warm room.The sprouts will be the optimum size for transplanting when they have grown 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 centimeters) long and have five or six leaves and a stout stem. Cut off the sprouts two inches (five centimeters) above the soil with a sharp knife. Because they’re unrooted, put them into soil almost horizontally, about two inches deep, making sure to allow two leaves to be above ground. Take care not to damage the shoot’s terminal bud. Immediately after you set them in their bed, water well.

The light soils that sweet potatoes prefer dry out rapidly, so as the plants grow, keep the soil moist, if possible, but never soaked. This encourages better root development. Keep the area well-weeded before the vines run too much. It’s best to do this by shallow scraping with a hoe, much as suggested for Irish potatoes. Gradually make a low hill around the stem of the vine by scraping up weeds and soil against it. Louisiana State University agricultural extension service says hilling reduces insect problems.

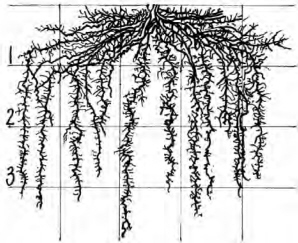

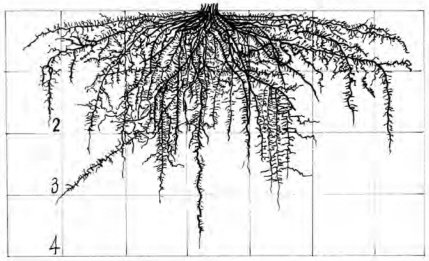

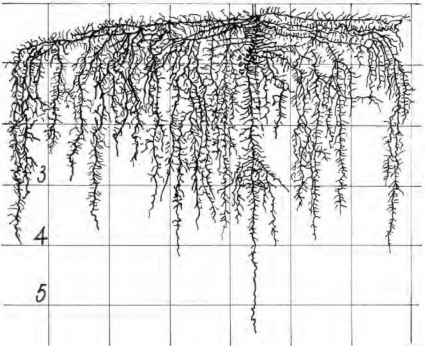

Figure 9.4: A sweet-potato plant at midsummer. With rows four feet (120 centimeters) on center, the vines from one row are reaching the plants in the next — as are the roots. No potatoes have formed yet. At harvest the vines and their roots will both have reached 14 feet (425 centimeters) at their greatest extent and be working to a depth of about 4½ feet (140 centimeters). Do not crowd sweet potatoes! (Figure 69 in RDVC)

Under good conditions, within two months of being set out the vines should entirely cover the spaces between rows. From then on do a bit of hand-weeding (and careful stepping) if you want the best results.

Pests and diseases. Commercial producers are distressed when any fraction of their crop fails to appear marketable, so pests and diseases are mainly a cosmetic worry to them. They are usually not a serious matter to the home gardener, except that there may be quarantines on the movement of potatoes and planting stock in states with major sweet-potato production. Be warned: at the time of writing, Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina have restrictions. Check with your local agricultural extension branch for information on your area.

The gardener’s most effective weapon to prevent problems is crop rotation. Rotation also helps simplify weeding.After at least two years of growing some other cleanly cultivated crops, the area will be relatively free of weed seeds and ready for sweet potatoes. A weedy sweet-potato crop is a stressed crop, a nonproductive crop, and a crop attractive to pests.

Do not repeat sweet potatoes on the same beds without a rest into other crops lasting at least three or four years. During that break you should not allow any of its pernicious relatives — like bindweed or morning glory — to grow. Finally, carefully clean up all vines, dig out all accessible root materials, and promptly hot-compost (or burn) them to greatly reduce pests for the next year. Due to companionate effects, legumes following sweet potatoes won’t grow well. It’s best to follow sweet potatoes with a brassica cover crop.

Varieties. In addition to the usual orange- or red-fleshed soft, sweet types, there are dry-fleshed white ones. These are quite popular with people from the Caribbean. I know of but one variety requiring less than 120 to 150 warm days and warm nights — Georgia Jet needs only 90.

Harvest, curing, and storage. Harvesting and storing seem to be the most rigorous aspect of growing sweet potatoes, especially growing early-maturing varieties in short-season climates. Under warm conditions the first harvest can begin about 90 to 120 days after setting out the shoots, but the potatoes will continue to swell in size for some time after they are first large enough to eat.Most of the sizing up happens rapidly during the last few weeks of growth, so watch closely. You want them sizeable but not overly large because eating quality suffers when they’re too big. (This is one reason not to make their soil too fertile.) There will come a point when all the sweet potatoes should be dug promptly.

It is important to harvest gently to minimize “skinning,” the scraping off of skin. Skinned potatoes don’t keep well. If the soil is quite dry at digging time, a light irrigation is helpful to soften it and reduce damage. However, if the earth is soggy when digging, the potatoes may crack open after harvest; they may even rot in the ground.

Select the roots you will use to make the next year’s seedlings while digging. These should be 1½ to 2½ inches (four to six centimeters) in diameter with smooth skins, a pleasant appearance, and no sign of insect damage or disease. They should also be taken from hills that made an abundant “nest” of potatoes.

Do not allow just-harvested potatoes to sit in the sun for more than one hour or they may scald, reducing their storage potential. And do not, if at all possible, harvest after frost. If you should be caught by a surprise frost, then harvest within days or the roots may begin to rot. Sweet potatoes still in the earth are badly damaged if they experience soil temperatures below 50°F (10°C).

After harvesting, the potatoes should be cured to heal any scrapes or injuries to their skins. Ideal conditions for this are a stable 85°F to 90°F (29°C to 32°C), humidity around 90 percent, and reasonable ventilation.Commercial growers have special rooms designed to maintain these conditions. North Carolina State University agricultural extension service advises the home gardener to use this simpler method: Once the roots have been removed from the garden, spread them out to dry for several hours away from direct sunlight. Once dry, put them in newspaper-lined boxes and leave them in a dry, ventilated area for two weeks for curing.When they are cured, store them in a cool, dry place (50°F to 55°F/10°C to 13°C).Wait a month until they’ve sweetened up and you’ll be ready to start cooking them. Most varieties of newly harvested potatoes do not taste sweet.Their flavor develops over time. In storage, beware of cold; if the roots get colder than 50°F (10°C) for even a few days, the core gets hard and loses quality. On the other hand, if they’re kept too warm for extended periods, they may shrivel, become stringy and pithy, and/or sprout prematurely.

Curing and storing sweet potatoes so that they’ll last the entire winter is more difficult than growing this easy crop, especially where weather conditions are cool at harvest time. If you master the art of keeping them until the next planting season, you may wish to start more than a few dozen seedlings in the spring because then this crop could become your nutritious basic staple, every bit the equal of the Irish potato.

Tomatoes, eggplant (aubergine), and peppers (capsicum or chilli)

Tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant are close relatives. Many varieties can be perennial where there is no frost.All are aggressive growers in suitable weather conditions, responding to fertilization by expanding to the limit of their moisture supply and rooting room. Gardening magazines occasionally show a photo of one trellised tomato plant covering the entire sun-facing wall of a house, and I was once introduced to a five-year-old Fijian eggplant bush that was five feet (150 centimeters) tall and six feet (180 centimeters) in diameter. Once a year it was trimmed back by half and its bed was mulched with a few gallons of chicken manure. I suggest new gardeners learn to grow tomatoes first; once they are mastered, peppers and eggplants will seem easier.

Growing details. Tomatoes are not frost-hardy; most varieties need 100 to 120 growing days from emerging to first ripe fruit.Where there are fewer than 150 frost-free days, gardeners must get at least a 50-day head start by using transplants. Those in warm climates may direct-seed tomatoes; usually these folks still use transplants to obtain extra production time.My advice: If your frost-free growing seasons exceeds 150 days, grow or buy only two or three early-maturing transplants of a bush determinate variety, enough to supply the table early in the season. Then directly seed a few more spots at the same time the seedlings are set out, and make these indeterminate varieties. This makes life simple. It also frees you from any temptation to buy a lot of tomato plants.

To direct-seed tomatoes immediately after there is no further frost danger, use hills spaced on at least four-foot (120-centimeter) centers. Gently press the soil back down to restore capillarity, make a thumbprint in the center of that mound about half an inch (1.25 centimeters) deep, put five or six seeds in that depression, cover with loose soil, and, if it is hot and sunny, water that spot every day for about a week. Progressively thin the seedlings to a single plant per hill.

You should lift tomato vines off the earth, freeing the fruit from damage by insects or rotting.You can stake up indeterminates, trellis them, guide their vines up hanging strings and wires, grow them in tall wire cages, etc.The best way I know to prune or train indeterminates (and there seem to be as many ways to do this as there are gardeners) is to follow their own growth pattern. Leaves, and the new vines emerging from their notches, form on the stem in threes. First, two weak side branches appear; the third one is a stronger side branch, and this pattern then repeats. During the first few months of the plant’s growth, remove all the weak side branches as soon as they appear and allow the third strong ones to grow. This is easily accomplished by pinching off the unwanted side shoots with your thumbnail. Thin both the main branch and also all the side branches that you allow to remain. Continue pruning this way until the plant has formed enough branches to suit whatever mechanics you have constructed to hold them up. After that, remove all side branches as soon as they appear.

The terms “indeterminate” and “determinate” refer to different growth patterns. All tomato vines grow by having one side branch emerge from each leaf notch. This side shoot will grow as freely as the main vine unless pinched off. Determinate vines grow only a few leaves (usually three) and then stop. The side branches continue the growth for three leaves and then stop, and so forth. Determinates tend to be tidy, compact plants.

Indeterminate varieties make a vine that keeps growing indefinitely from its end; its side branches also grow indefinitely. The result is that the vines on indeterminates are much longer, and usually the length of stem between each leaf is also longer, so they are lanky and spread aggressively.

Both sorts will keep producing new fruit and covering new ground until frost — as long as the plant can find unoccupied soil in which to make roots. If the root zone gets crowded, they become stressed, their production slows a lot, and often the vine becomes diseased or will be attacked by insects.The longer your frost-free growing season is, the more growing space you should give tomatoes.

The root systems of determinate varieties closely match their compact above-ground growth. Determinates set more fruit sooner, ripen it sooner, and yield more heavily for a shorter time. Because of their growth habit, determinates are not staked up or trained and are bred so as to hold much of their fruit slightly above the soil. Short-season gardeners should probably only grow these types because they’re inevitably earliest. Generally the flavor of determinates is second-rate because the vine carries more weight of fruit in proportion to the amount of leaf area it makes to fill those fruit with taste and nutrition.

An old-fashioned way to lift determinate vines enough to prevent most damage is to spread a few inches of dry brush to cover where they are to grow and let the vines grow over it.

Pests and diseases. There are many diseases; most are a problem only in commercial fields. If the roots have room to expand, the weather is favorable, and the soil is reasonably fertile, the vine usually won’t become sick.

Fruit worms are the same larvae as the ones that eat corn and may be controlled by spraying Bt (see the section on the corn earworm in Chapter 8).

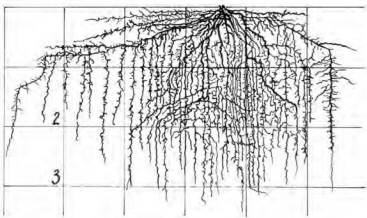

Figure 9.5: An indeterminate tomato plant, spaced four feet by four feet (120 by 120 centimeters), shown two months after transplanting. The tops aren’t bumping yet, but the root systems are. At the time of the first frost, this plant had roots extending five feet (150 centimeters) from the center, and the entire system had thickly penetrated an eight-foot-diameter (245-centimeter) circle to a depth of 42 inches (105 centimeters). Clearly, tomatoes need a lot of growing room to do their best. (Figure 73 in RDVC)

Hornworms eat leaves; they also die after eating a bit of Bt. Blossom-end rot will stop being a problem on most varieties once your subsoil offers sufficient calcium; it can take a few years of light applications of lime for enough calcium to build up in the subsoil.Have faith: end rot will fade away.

Varieties. There are a great many varieties of tomatoes. Hybrid varieties are only slightly more vigorous.Their big advantage is that they can be resistant to more diseases at once, which is important to commercial growers who run down their soil’s organic matter content, overcrowd the plants, and don’t rotate out of tomatoes often enough. Some heirlooms have superior flavor but may not be well-adapted to cool or dry climates, and they rarely carry any disease resistance at all. I suggest that you only experiment with heirlooms. Try a new one every year, but mainly grow the tomato varieties proven to work in your area.The best flavor is found in slicing (firm-fleshed, not watery) varieties that require warm humid nights. These are often called “beefsteak.”However, in maritime climates these classics usually fail to ripen, which is another reason to check with the local experts about locally adapted varieties. Some varieties may deal better with diseases present in your area, too.

Indeterminate cherry tomatoes are the most aggressively growing of all types and are best suited to dry gardening. If you’re making sauce or paste, use varieties bred to contain less moisture. They cook down in half the time, saving a great deal of energy. These sorts are also superior for drying. Finally, a relatively new sort has come out called Longkeeper. It and its competitors ripen extremely slowly; after you pick it when it’s green, the fruit develops a waxy tough skin that holds in moisture, lasting a lot longer while ripening slowly in the pantry.They taste pretty good, especially when the only comparison comes from the supermarket. I suspect that Longkeeper was bred from an old Burpee classic called Golden Jubilee, a late-maturing yellow beefsteak type that has, in my opinion, the best flavor of any tomato. I always grow one Golden Jubilee plant even though it is too late for my climate and even though I only get a few fully ripe fruit toward the end of summer unless the year has proved unusually warm. Still, the full-sized green ones are among our best inthe-house ripeners.

Peppers and eggplant are less-vigorous close relatives of the tomato. They too are self-pollinating, but have a slight tendency to outcross. If you are saving seed, give varieties about 20 feet (six meters) of isolation. It’s especially important to isolate hot peppers from sweet ones.The seed-saving procedure is identical; let the fruit get dead-ripe first.

Peppers are sometimes direct-seeded where the growing season exceeds 150 days (I know someone in Maryland who does that); I wouldn’t try it with eggplant unless the growing season exceeded 180 days. In short-season areas or in maritime climates, growing hybrid peppers is highly advantageous. In climates where the summers aren’t hot, if you don’t have a greenhouse, hybrid eggplant may be essential, and the best of the lot in Cascadian trials is Dusky Hybrid. In chilly areas, it may be to your advantage to grow peppers and eggplant on top of a black plastic mulch that covers their entire wide raised bed. The mulch warms the soil a few degrees and also increases the nighttime air temperature a few degrees.This little rise in temperature makes all the difference. It is not necessary to use drip or trickle irrigation beneath such mulch in the garden. Simply make the bed perfectly flat. Then lay and anchor the mulch and set transplants through small “X” slits.When overhead watering or when it rains, puddles will form in slight dips and depressions. Poke small holes in every one of these spots to let the water flow through.

Harvest and storage. I pick my scarce first fruits when they’re light orange because I hate to see any of them damaged by slugs or woodlice.After trellised indeterminates are ripening higher off the earth, there is less danger of damage (and many more fruit to spare), so I let them develop a completely vine-ripened flavor.At the end of the season I bring all full-sized green tomatoes into the house and keep them in airy baskets in a cool part of the house to ripen over the next few months.

To improve the performance of determinate varieties, about eight weeks before the first expected frost, pinch off about half the flower clusters as they appear. This lightens the fruit load and enhances size and flavor. About four weeks before the first expected frost, pinch off over three quarters of all the flower clusters as they appear.

Saving seed.There is little advantage to growing hybrid tomatoes, so you may as well grow open-pollinated sorts and save your own seed.Tomatoes (and peppers and eggplant) are self-pollinating, and you can save seed from a single plant. Let the fruit used for seed extraction get completely ripe on the vine; it’ll sprout better and store longer if you do.Then bring these dead-ripe fruit into the house, keep them in a warm place, and let them ripen even further for another few days.

Cut the tomatoes in half crosswise, exposing all the cells inside. With your finger, scoop out the juicy (seedy) pulp into a bowl. Put that watery mixture into a small jar that holds double the volume you are putting into it. Allow it to stand on the counter for a few days in a warm room. It’ll ferment, fizz, and foam, and white mold may grow on top.That’s fine.The acids caused by fermentation dissolve the sprouting inhibitors within the seed, making it much more certain to germinate. Swill the liquid around in the jar once a day to help settle the seeds out of the froth on top.Within three to five days most of the seeds will have settled on the bottom and most of the solids will be floating on the top.Now gently fill the jar with water, allow the seeds to resettle to the bottom, and gently pour most of that water off without losing many seeds. Refill and repeat this until the water is clear and the solids are gone.The few seeds you will lose doing this are to your good; these float to the top because they are lightweight and unripe.

Pour the contents of the jar through a tea strainer to catch the seeds. Rinse the jar a few times to get them all out. Then rinse the seeds in the strainer under running water until clean. Dump the seeds on top of several thicknesses of newspaper and let them dry for a few days before you put them away in a paper envelope.With most varieties, a few ripe tomatoes will provide enough seeds for the entire neighborhood.

Winter squash (pumpkin), zucchini, melons, and cucumber

Cucurbits are so similar that if you have known one, you know them all. The easiest one to start with is squash, because it is the most vigorous, most tolerant of chilling, and most tolerant of heavy soils.

Growing details. The key to success with cucurbits is to wait until the soil warms up enough before sowing. And you should almost always directly seed; they don’t transplant well.Whether while sprouting or when growing on, cucumbers need more warmth than squash, and melons (especially watermelons) need more than cucumbers. Sow squash and pumpkins after soil has warmed to 60°F (15°C) and ideally sow during a week of sunny weather.After squash seedlings are up and have begun to grow well, sow cucumbers. As soon as cucumber seedlings are up and beginning to grow well, sow melons. This timing method matches the steadily increasing temperature of soil in spring.

Any time the soil turns chilly and damp while cucurbit seeds are sprouting, they may die. Cucurbits are more sensitive to chill and damp before coming up than after. Should any young seedlings (or seed not yet emerged) experience a spell of chilly or rainy weather, remedy the situation using this method: As soon as the weather settles, resow at another spot in the same hill. If both sowings end up growing well, progressively thin both and finally choose the plant that grows the best. Sometimes in a chilly damp spring, a sowing made a week or ten days later will outgrow an earlier one that barely emerged, shivering and shaken.

For the same reason, you should be reluctant to water sprouting cucurbit seeds. It’s better to chit them first, plant them into moist warm soil, and then not water them at all until they emerge.

Cucurbits grow fast in full sun and in fertile soil (most fruiting plants do). Since the mainly shallow root system of all cucurbits is at least as extensive as their tops are (with bush summer squash, the roots may spread significantly more than the leaves do), the entire area their vines will ultimately cover should be made fertile; additionally, to get the seedling off and growing fast, sow seeds in a hill with extra fertility beneath it.

On hot sunny afternoons, gardeners often shrug off temporary wilting of cucurbits as unimportant. The attitude is: Inevitably the plant recovers, don’t worry. This is not correct; any wilting is a big stress and greatly reduces plant health and overall yield. Cucurbits don’t wilt on hot days when only one plant grows in each hill and the plant does not share its root zone. So where squash borer is not a problem (and the insect is rarely a problem with cucumber and melons), do not grow two or three plants per hill. Start three but thin to one by the time the vines start to run.

Watermelons are intolerant of heavy soils.

Pests and diseases. See the discussion in Chapter 8.

Varieties. Hybrid squash varieties now dominate in seed catalogs. Consequently, OP summer squash varieties have degenerated, excepting the old Yellow Crookneck (vining), which is by far the best-tasting of all summer squash and resists pests better, too. Hybrid winter squash may outyield the classics by half again, but they don’t taste any better, and for most people the production of one or two good hills of ordinary varieties is a gracious plenty. genuine heirloom Sweet Meat (from Harris Seeds or Territorial Seeds) or one of the somewhat shorter-storing delicata types (including Sweet Dumpling). Acorns don’t keep well at all.Australians have an especially long-keeping pumpkin named Queensland Blue (what North Americans call winter squash, people Down Under call “pumpkins”) that makes the best pumpkin soup you ever tasted. Johnny’s Selected Seeds sells an heirloom variant of this from the state ofWestern Australia called Jarrahdale.

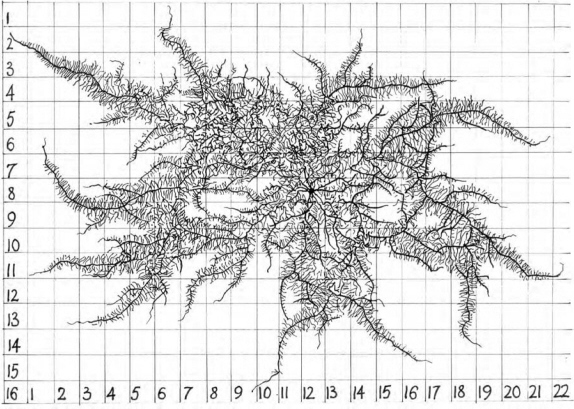

Figure 9.6: A typical cucurbit root system — this one is Rocky Ford cantaloupe in midsummer. The drawing is viewed from above. The extensive root system is shallow, rarely going down more than two feet (60 centimeters). Winter squash, a more vigorous plant, makes roots covering half again more area. With cucurbits, you can assume that the roots are always at least as extensive as the vines are. (Figure 85 in RDVC)

Of cucumbers, the old sprawling classic “apple” or “lemon” is best adapted to lower levels of fertility and soil moisture. Hybrid cucumber seed is affordable; hybrid melon seed isn’t.However, in the cool nights of a maritime climate, only the earliest of hybrid melons will produce anything, and only when grown atop a wide sheet of black plastic. I spread a piece about six feet (two meters) wide, anchor it on the edges, and put one vine every four feet down the row. That’s the only way I can harvest ripe melons in a maritime climate.

Harvest and storage. Everybody Else says zucchini and other summer squash stop yielding much after a month or so, but it doesn’t have to be that way. If you give them growing room, the plants will produce more growing branches, more flowers will form, and the yield will steadily increase until the weather turns against the crop. So don’t crowd them. I have grown bush varieties in hills on five-foot (150-centimeter) centers with great results. (“Bush” squash are really just vines with short spaces along their stem.)

Remove all overlooked oversized fruit from summer squash and cucumber vines because the burden of forming seed reduces formation of new fruit.

Winter squash don’t taste great until they are fully ripe.They have reached that state when the stem attaching the fruit to the vine has shriveled and become brittle, revealing that it is no longer passing vascular fluid.Most winter squash in the species Cucurbita pepo (acorn, delicata) don’t store as long as those in C.maxima (Hubbard, buttercup) or C. moschata (butternut). Ideal storage is 60°F (15.5°C) with low humidity and good air circulation.Warmer and dry is better than cool and damp. Storage time has a lot to do with variety. I’ve also found that leaving winter squash outside to experience more than the first light touch of frost greatly lowers their storage potential. Curing also helps lengthen storage. Bring them inside where it is warm and dry for two weeks; this toughens their skin. We heap ours up in the dining room. Then, cured, they go to a cooler dry place.

Cantaloupe, honeydew, and similar melons are ripe when the vine slips off the fruit with only slight pressure.They do not ripen after being picked,which is why supermarket melons, inevitably harvested when unripe (and still hard enough to pack in a box and ship), are inferior.To determine when to cut watermelons from the vine, you must thump them and knowledgeably listen to the sound they make. I can’t explain this talent in words. It must be developed with practice.

Saving seed. Cucurbits are pollinated by bees. Isolation of at least half a mile (800 meters) will prevent enough crossing for home-garden purposes.There are three commonly grown squash species: Cucurbita pepo, C. maxima, and C. moschata. These species do not cross, but every variety within one species does cross with every other.All summer squash, delicata types, acorn squash, and most jack-o’-lanterns are C. pepo.The large winter squash varieties are usually maxima.

All but a few cucumber varieties are within the same species and cross.

Canteloupes (rockmelons) don’t cross with honeydew types. Some specialty melons are unique species. Check the seed catalog for their Latin names and assume different species won’t cross-pollinate. The seed is ripe when the fruit has become completely ripe (slips the vine).

Practically speaking, all this interesting information is irrelevant to the home gardener; when it comes to growing your own seed for these species, I strongly suggest you don’t try for more than one generation unless the seed-producing population exceeds 25 plants. Saving seed from only a few cucurbit plants leads to inbreeding depression of vigor; within a few generations the seed will barely sprout or grow. Few gardeners grow 25 winter squash vines! However, the seed is long-lasting and the first generation’s seed collected from just a few fruit will supply you and the whole neighborhood for the next ten years if properly stored. My suggestion is that at least every other generation you buy a packet of new stock.

Some maxima varieties have seeds that taste good, but some don’t. Sweet Meat’s seeds, for example, make great munching. You may be discarding the best of this vegetable’s nutrition if you don’t extract, dry, and eat its seeds.

Beets (beetroot) and Swiss chard (silverbeet)

These quite different vegetables derived from the same wild plant, whose Latin name, Beta, became “beet” in English. The vegetable “beet” was bred for the succulent sweet root; thinnings grown to the stage of developing baby-sized beets are often cooked, tops and all. Swiss chard was selected to emphasize large tender leaves, but dig one up and you’ll see a poorly formed beetroot. Beta, with a huge reservoir for moisture storage in the top of its root and a deeply adventuring root system, is good at handling long-lasting dry spells. If there is nutrition accessible in the subsoil, Beta does not need hugely fertile topsoil.

Growing details. Technically, beet seeds are fruits; each usually produces several seedlings.The commercially produced seeds can be stored a long time; six years is normal and ten isn’t unusual. So if you get some beet or chard seed that sprouts poorly, take it as an insult; it had to have been really sad old stuff. To get well-formed beets, careful thinning is essential. Shortly after germination, reduce the thickest of the clumps, but do so cautiously as there will usually be a fair number of mysterious seedling disappearances. Postpone the final, precise thinning until the plants are about four inches (10 centimeters) tall.Then thin them to whatever spacing you’ll want the mature beets to be growing to.

Varieties.Where winter consists of only frosts or chilly weather, two historic and virtually identical varieties, Lutz or Winterkeeper, are bred to make enormous roots that hold for months. Cylinder varieties are bred for canneries that want to slice rounds and also need quick-cooking vegetables; they have little fiber.White beets (sugar beet crosses) have a sweeter flavor.

Harvest, storage, and use. Most varieties of beet will continue enlarging without becoming woody or tasteless if only they have room to grow.Harvesting by pulling every second beet in the row helps the patch remain in better eating condition.Thinning to a wider spacing at four inches (10 centimeters) tall and using wider between-row spacings helps even more. I once dry-gardened delicious beets spaced one foot (30 centimeters) apart in rows four feet (120 centimeters) apart. After five entirely rainless months, each root was nearly the size of a volleyball and still delicious.

In mild climates, beets may overwinter in their bed. In Cascadia — where in the rare year a short spell of freezing weather may ice their crowns, killing them — burying the crowns under a few inches of soil is sufficient protection. Beets root-cellar well in a barrel of moist sand.

Because this crop is so well-suited to being a vegetable staff of life, I thought I’d suggest a few ways you can use beets that most people do not know about.

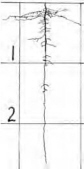

Figure 9.7: A beet root system about 110 days after sowing seeds. Clearly a single plant is designed to make use of all the moisture and nutrition from a cylinder of soil about two feet (60 centimeters) across and seven feet (215 centimeters) deep. Thus, in dry gardening, a useful spacing for this drought-tolerant crop would be about one foot (30 centimeters) apart in rows about four feet (120 centimeters) apart. (Figure 21 in RDVC)

Beets may be baked like potatoes and are delicious.This method of preparation retains more of their nutrition than boiling does.

Raw, grated-beet salad can be delicious in areas where the subsoil offers balanced fertility; given proper nutrition, the beetroot will not have any of that back-of-throat-rasping sensation many associate with raw beet. Mix grated beet with bits of navel orange and minced mild onion; dress with a bit of lemon juice and black pepper.

Saving seed. Beets must overwinter before making seed the next spring.

Wind-pollinated, they need at least a quarter mile (400 meters) of isolation for rough purity. Seedmaking plants occupy a lot of space and inevitably make lots of seed. In early spring you should replant the roots to the depth of their crown at least one foot (30 centimeters) apart, in rows three to four feet (90 to 120 centimeters) apart. In midsummer, when much of the seed is dry on the stalk, harvest the whole plants and let them finish drying to a crisp under cover on a tarp.Then rub the seeds off their stalks and winnow to clean away the dust and chaff. To maintain a variety through more than one generation, include at least 25 plants in the gene pool. Four to six plants will make several pounds of seed that will last a decade if it has not been rained on or irrigated during the drying-down period.This is hard to achieve in areas with summer rain, which is why commercial beet seed is grown in Cascadia, where the summer is reliably dry.

To make chard (silverbeet) seed where the snow flies, dig half a dozen plants with as much root as you can get up, cut off their larger leaves, plant them in large tubs or beds of earth in the root cellar over the winter, and then transplant them back outside in spring. In moderate winters it might work to hill up soil around and actually over the plants, and then uncover them in early spring. Otherwise they are like beets and will cross with beets.

Sweet corn

Growing details. I prefer growing corn with a bit more elbow room than most because the plant has a natural tendency to tiller,meaning it will put up additional ear-bearing stalks if there is enough growing room. And even if a plant doesn’t tiller (tillering is a trait modern breeders try to eliminate because ears forming on secondary stalks are smaller), having a bit more soil to access will protect it against drought and also make the main ears get a bit bigger.

Where soil moisture is not a problem, each plant should exclusively control at least 2  square feet (2,000 square centimeters). Eighteen inches (45 centimeters) on center or nine inches (23 centimeters) apart in rows 36 inches (90 centimeters) apart, or eight inches (20 centimeters) apart in rows 42 inches (105 centimeters) apart all work out to be about the same amount of growing room per plant.

square feet (2,000 square centimeters). Eighteen inches (45 centimeters) on center or nine inches (23 centimeters) apart in rows 36 inches (90 centimeters) apart, or eight inches (20 centimeters) apart in rows 42 inches (105 centimeters) apart all work out to be about the same amount of growing room per plant.

Where low soil moisture threatens to be a short-lasting problem, you might increase the spacing to nine inches (23 centimeters) apart in rows 48 inches (120 centimeters) apart. Using a row spacing greater than 48 inches makes little sense for most varieties (see the root system drawing).Where a severe shortage of rain during the growing season is a certainty and watering is not possible, the maximum amount of space you should ever give a single sweet corn plant is about 16 square feet (1.5 square meters) or four-foot centers, imitating traditional Native American gardening; growing in hills spaced four feet on center, putting four seeds in every hill, and then ending up with one plant (one for the worm, one for the crow, one to rot, and one to grow) by thinning progressively if necessary.

Because the ears are wind-pollinated and the pollen is heavy, when corn is grown in a single long row you may find many ears will be only partly filled. It is best to grow corn in a patch at least two rows wide, with at least six plants to the row. It is better to make the entire corn bed moderately fertile, rather than confining soil amendments to the rows or hills.However, extremely high levels of fertility aren’t needed for this medium-demand vegetable.