2

Problems with Evolution

Few people this century have avoided exposure to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. His book, The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, first appeared in late November 1859 and quickly passed through three editions.

By proposing chance rather than divine purpose as the agent of our origins, Darwin’s theory confronted, head-on, the literal understanding of the biblical account of creation. And, by a single reference to an evolutionary connection between man and apes, it became widely ridiculed as the ‘Monkey Theory’. In a debate with evolutionary biologist T. H. Huxley, Oxford’s Bishop Wilberforce inquired, with silken sarcasm, ‘And do you claim descent from an ape on your grandfather’s or your grandmother’s side?’

It was true, of course, that the implications of Darwin’s theory were inimical to religion, for it implied that life was a random process which had no purpose other than survival.

Darwin’s theory rests upon two fundamental points:

1) Small random changes in structure or function occur in nature. Those which are advantageous are, by natural selection, retained; those which are not are discarded.

2) This process of evolutionary change is gradual, long-term and continuous: it occurs now just as it occurred in the past. The cumulative effect of these small changes over long periods of time is to create new species.

The theory was certainly attractive: it had logic, simplicity and, reassuringly, appeared self-evident. Within a decade Darwin had gained the widespread and powerful scientific support which continues today. The orthodox scientific consensus was summed up in 1959 by Sir Julian Huxley, Professor of Zoology and Physiology at King’s College, London, when he stated that Darwin’s theory of evolution was ‘no longer a theory but a fact’.1 Professor of Zoology at Oxford Richard Dawkins expressed himself just as bluntly in 1976, opining that, ‘Today the theory of evolution is about as much in doubt as the theory that the earth goes round the sun…’2

It comes as a shock, then, to read Stephen Jay Gould, Professor of Zoology and Geology at Harvard University, observing in 1977 that, ‘The fossil record offered no support for gradual change.’3 This is a direct challenge to one of the fundamental props holding up Darwin’s theory.

In 1982 David Schindel, Professor of Geology at Yale University, writing in the prestigious journal Nature, revealed that the expected gradual ‘transitions between presumed ancestors and descendants… are missing’.4

What has happened? Did we all blink at an important moment? Have we all missed something?

We thought the debate over evolution had long been settled, but we were wrong. The origin of species is as much a mystery now as it was in Darwin’s day.

The Origin of Species

Darwin argued that the development of any one species from its ancestor would be by a long and gradual progression which passed through a countless number of intermediate forms. He realized that, if his theory was correct, thousands of these intermediate forms must have existed. And he further realized that upon the existence of these forms his theory stood, or fell. He wrote, ‘the number of intermediate and transitional links, between all living and extinct species, must have been inconceivably great. But assuredly, if this theory be true, such have lived upon this earth.’5 But ‘Why?’ he asked, raising his own doubts, ‘do we not find them embedded in countless numbers in the crust of the earth?’6 He was painfully aware of the lack of such fossils in the geological strata. He stalled: ‘the answer mainly lies in the [fossil] record being… less perfect than is generally supposed’.7

Nevertheless, this fact continued to haunt him and he proceeded to devote an entire chapter of his book to ‘the imperfection of the geological record’. Despite his confident arguments, he clearly retained considerable unease about the situation for he felt the necessity to place in print his confidence that in ‘future ages… many fossil links will be discovered’.8

Enthused by his theory and the certainty that a focus upon larger areas of fossil-bearing rocks would satisfactorily resolve this ‘imperfection’, geologists and palaeontologists (scientists who study fossils) have devoted enormous effort towards filling the gaps in the fossil record. Amazingly, given the vast resources applied to the task over the years, the effort has failed. Professor Gould revealed that, ‘The extreme rarity of transitional forms in the fossil record persists as the trade secret of paleontology.’9

In 1978 Gould’s colleague, Professor Niles Eldredge, confessed in an interview that, ‘No one has found any “inbetween” creatures: the fossil evidence has failed to turn up any “missing links”, and many scientists now share a growing conviction that these transitional forms never existed.’10 Professor Steven Stanley writes, ‘In fact, the fossil record does not convincingly document a single transition from one species to another. Furthermore, species lasted for astoundingly long periods of time.’11 No one, for instance, has ever found a fossil giraffe with a medium-sized neck. If the fossil record fails to show the expected links, what then does it show? And what does it prove?

The Fossil Record

The fossil record, as we know it, starts at a period called by geologists the Cambrian, which they date to about 590 million years ago. Some minute fossilized remains have been found in rocks from the early years of this time: some bacteria and some very curious creatures unlike anything known before or since – the Ediacaran fauna dating from around 565 million years ago. But they were all apparently extinct shortly afterwards. It is as though a few training exercises were scribbled upon the book of life following which a distinct line was ruled across: thereafter real evolution began; or, at least, something began.

And it was dramatic: for the animal kingdom, everything came at once. Such was the sudden and mysterious blossoming of life’s variety at this time that, as we have seen, scientists speak of the Cambrian Explosion which they date around 530 million years ago.

The most startling discovery was that every known body shape of animals, either as fossils or alive today, began here. At this time life chose its basic forms and has never seen fit to change.

What is more, even though the full Cambrian period is held to have lasted for some 85 million years, the actual appearance of these new forms probably occurred in about 10 million years or less.12

In other words, Life’s history on earth reveals about 2 per cent creativity and 98 per cent subsequent development.

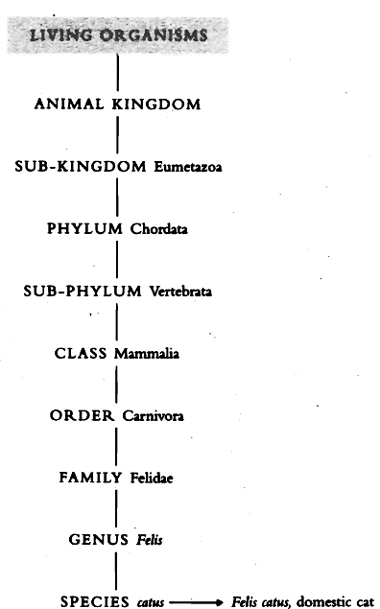

It is by body plan that all living creatures were first classified. A complex system has developed which divides all life into two great kingdoms: the animal kingdom and the plant kingdom. These, in turn, are subdivided, firstly into phyla (the plural form of phylum),

Simplified diagram of animal classification.

derived from the Greek for ‘tribe’, then further divided progressively down to species and sub-species.

The animal kingdom is generally divided into thirty-seven phyla. All of these phyla arose during the Cambrian period. Since that time evolution has just tinkered with modification of the basic plan. Furthermore, there is no evidence whatever for any previous development of them. There is no evidence that they ‘evolved’ as we understand the term in its Darwinian sense. They all just appear in the fossil record as fully formed, highly distinct, creatures.

Scientists are bemused. Drawing attention to the fact that ‘all the evolutionary changes since the Cambrian period have been mere variations on those basic themes’,13 Professor Jeffrey Levinton of State University of New York, asks, ‘Why are the ancient body plans so stable?’14 He has no answer.

What is very clear from the geological record is that this stability is the norm. Fossil forms of animals or plants appear, flourish for millions of years and then disappear, but still in much the same shape. Whatever change is seen is gradual and limited mostly to size: the entire animal or plant, or certain of its features, grows larger.15 It is not seen to change into another form, even one relatively close: a mouse has never evolved into a rat; a sparrow has never become a blackbird.

Furthermore such change as has occurred seems very selective. A great number of creatures still living today have survived for very long periods of time without any evidence of significant change in their form at all. This is contrary to all the expectations of Darwinian evolution.

Oysters and mussels are much the same now as they were when they first appeared some 400 million years ago. The coelacanth and lungfishes have been living for around 300 million years without significant change. Sharks have remained the same for 150 million years. Sturgeons, snapping turtles, alligators and tapirs have all shown stability of form for over 100 million years. Modern opossums differ only in minor details from those which first lived 65 million years ago. The first turtle had a shell like it has today; the first snakes are almost identical to modern snakes; bats too have remained stable, as have frogs and salamanders.

Has evolution then stopped? Or is some other mechanism or agency at work?

An example, often used to demonstrate evolution, is that of the horse. It is supposed to have begun with the diminutive, four-toed, Hydracotherium,16 which lived 55 million years ago and developed into the modern Equus which has been living for about 3 million years. Elegant and convincing charts and museum displays showing the progressive evolution of the horse have been widely seen. They cleverly show how the toes gradually reduce to one, how the size of the animal greatly increases and how the teeth change with its change in diet.

However, experts are now generally agreed that this line of slow but sure alteration from an animal the size of a dog into the large horse of today, is ‘largely apocryphal’.17 The truth is, as usual with the fossil record, that there are many gaps between the various species of fossil horse which are placed into this series. Beginning with the first, Hydracotherium, its own ancestry a mystery, there is no known link to the assumed ‘second’ horse, and so on.

What we have is not a line of development, nor even a family tree leading to modern Equus, but a great bush of which only the tips of the many branches are apparent – leaving open any question regarding the existence of its trunk. At any one time several differing species of horses were alive, some with four toes, some with fewer, some with large teeth, some with small. Horses too grew large, then small, and then large again. And, as a constant irritation throughout, there is a lack of interconnecting species.

Finally, we must also admit that the supposed ancestral horse is not so different from a modern horse. Apart from a few minor changes with feet and teeth and the increase in size, little of significance is different. This very minor alteration, championed as proof of evolution, even if true, is hardly impressive given the 52 million years involved. Bluntly, to regard this pseudo-sequence as in some way a proof of evolution is less an act of science than one of faith.18

The Abrupt Origin of Species

The fossil record is characterized by two aspects: the first, as we have seen, is the stability of the plant or animal forms once they have appeared. The second is the abrupt manner in which these forms emerge and, for that matter, subsequently vanish.

New forms arise in the record without obvious ancestors; they leave just as suddenly without any obvious descendants. One could almost call the fossil evidence a record of a vast series of creations, related only by choice of shape, not by evolutionary connections. Professor Gould summarizes the situation: ‘In any local area, a species does not arise gradually by the steady transformation of its ancestors; it appears all at once and “fully formed”.’19

We can see this process occurring almost everywhere. When, for example, about 450 million years ago, the first fossils of terrestrial plants appear, they do so without any previously recorded development. Yet, even this early, all the major varieties are evident. According to the theory of evolution, this is impossible – unless we can accept that none of the expected linking forms has been fossilized. Which seems rather unlikely.

Similarly, although the period preceding the appearance of flowering plants is one of great fossil diversity, no ancestral forms have ever been found for them; their origins too remain obscure.

The same anomaly is found in the animal kingdom. Fish with backbones and brains first appear about 450 million years ago. Their direct ancestors are unknown. And in a further blow to evolutionary theory, these first jawless but armoured fish had a partly bony skeleton. The commonly produced story of a cartilaginous skeleton (as seen in sharks and rays) evolving into a bony skeleton is, bluntly, wrong. In fact, these non-bony fish appear in the fossil record some 75 million years later.

Furthermore a significant stage in the apparent evolution of fishes was the development of a jaw. But the first fish with a jaw appears abruptly in the record without any earlier jawless fish able to be designated as the source. An additional curiosity is that lampreys – jawless fish – still happily exist today. If a jaw provided such an evolutionary advantage, why should such a fish still live? Similarly

|

Total number of living orders of land vertebrates: |

43 |

|

Total number of these found in the fossil record: |

42 |

|

Therefore, percentage discovered as fossils: |

97.7% |

|

Total number of living families of land vertebrates: |

329 |

|

Total number of these found in the fossil record: |

261 |

|

Therefore, percentage discovered as fossils: |

79.3% |

|

We can conclude that the fossil record is a competent record giving an accurate sample of the life forms which have existed on earth. Therefore, appealing to an imperfection of the fossil record as a way of explaining the gaps is not very convincing. |

The accuracy of the fossil record.

enigmatic is the development of amphibians, aquatic creatures yet able to breathe air and live on land. As Dr Robert Wesson explains in his book Beyond Natural Selection,

The stages by which a fish gave rise to an amphibian are unknown… the earliest land animals appear with four good limbs, shoulder and pelvic girdles, ribs and distinct heads… In a few million years, over 320 million years ago, a dozen orders of amphibians suddenly appear in the record, none apparently ancestral to any other.20

Mammals too show this abrupt pattern of development. The earliest was a small animal skulking furtively around during the era of the dinosaurs, 100 million or more years ago.21 Then, after the mysterious and still-unexplained demise of the latter (about 65 million years ago), a dozen or more groups of mammals all appear in the fossil record at the same time – around 55 million years ago. Fossils of modern-looking bears, lions and bats are found at this period. And, to complicate the picture, they appear not in one area but simultaneously in Asia, South America and South Africa. On top of all this uncertainty, it is not sure that the small mammal of the dinosaur period was actually the ancestor of the later mammals.22 Gaps and enigmas abound wherever one looks in the fossil record. There are no known fossil links, for example, between the first vertebrates and the primitive earlier creatures – the chordates – which are the presumed ancestors.23 The amphibians alive today are markedly different from the earliest known: there is a 100-million-year gap in the fossil record between these older and later forms.24

Darwin’s theory of evolution would seem to be crumbling away before us. His idea of ‘natural selection’ may conceivably be saved, but only in a significantly modified form. It is clear that there is no evidence for the development of any new plant or animal forms. It is only once a living form has appeared that perhaps natural selection has a role. But it can only work on what is already existing.

Students at school and university, as well as scientists, carry out breeding experiments with the fruitfly, Drosophila. They are taught that they are demonstrating the proof of evolution. They create mutations of the fly, give it different coloured eyes, a leg growing from its head, or perhaps a double thorax. They might even manage to grow a fly with four wings instead of the usual two. But these changes are only modifying already existing features of the fly – four wings, for example, are but duplicates of the original two. A new internal organ has never been created, neither has a fruitfly ever been turned into something resembling a bee or a butterfly.25 It has not even been turned into another type of fly. It remains, always, a variant of the genus Drosophila. ‘Natural selection may explain the origin of adaptations, but it cannot explain the origin of species.’26 And even this limited application runs into problems.

How, for example, can natural selection explain the fact that humans – a single species – have dozens of different types of blood group? How can it explain that one of the earliest fossil types known, the Cambrian-period trilobite, has an eye of such complexity and efficiency that it has never been bettered by any later member of its phylum? And how could feathers evolve? Dr Barbara Stahl, author

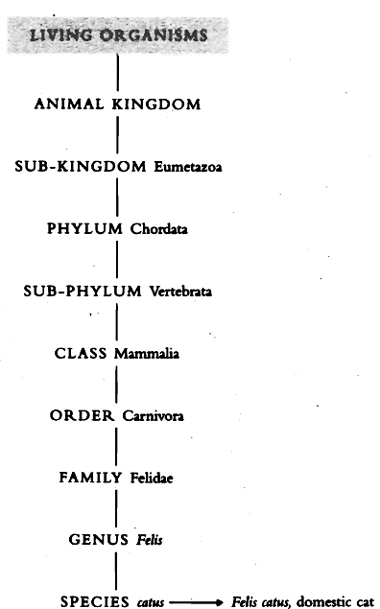

Apparent evolution of vertebrates. This diagram represents the abundance of vertebrate groups over time. The dotted lines are the missing links required by evolutionary theory to link these groups. These links have not been found in the fossil record.

of a standard text on evolution, admits, ‘How they arose, presumably from reptiles’ scales, defies analysis.’27

Even at the beginning Darwin knew that he faced profound problems. The development of complex organs, for example, strained his theory to its limit. For until such an organ was functioning, how could it be sufficiently advantageous for natural selection to encourage it to endure? As Professor Gould asks, ‘Of what possible use are the imperfect incipient stages of useful structures? What good is half a jaw or half a wing?’28

Or perhaps half an eye? In the back of Darwin’s mind the same question had arisen. In 1860 he confessed to a colleague that, ‘The eye to this day gives me a cold shudder.’29 As well it might.

The final example – proof if you will – that natural selection, if indeed a valid mechanism for change, has more to be understood, is the case of the waste-disposal habits of the sloth given by Dr Wesson:

Instead of defecating on demand, like other tree dwellers, a sloth saves its faeces for a week or more, not easy for an eater of coarse vegetable material. Then it descends to the ground it otherwise never touches, relieves itself, and buries the mass. The evolutionary advantage of going to this trouble, involving no little danger, is supposedly to fertilize the home tree. That is, a series of random mutations led an ancestral sloth to engage in unslothlike behavior for toilet purposes and that this so improved the quality of foliage of its favorite tree as to cause it to have more numerous descendants than sloths that simply let their dung fall…30

Either evolution has other modes of ‘natural selection’ that we have not yet even guessed at, or something else entirely must be used to explain the abrupt scatter of the fossil record – a cosmic sense of humour perhaps?

Irregular Evolution

The problems with the fossil record have been known from the very first. For a century or so scientists simply hoped that they would go away, removed by some discoveries which bridged the gaps. Or, perhaps, by the discovery of certain proof that the gaps were caused by an intermittent geological process rather than any problems with evolution. Eventually, however, the strain became too much. The consensus broke in 1972 when Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge jointly submitted a radical paper to a conference on evolution.31 Their paper directly contradicted Darwin’s theory.

They put forward the argument that even though the fossil record was certainly far from satisfactory, the observed abrupt appearances of new species was not evidence of an imperfect fossil record; rather, it reflected reality. The origin of species might not be a gradual evolutionary process but a process in which long periods of stability were occasionally punctuated by sudden massive changes in living forms. By this argument, Gould and Eldredge could account for the absence of ‘missing links’: they held that they did not exist.

However well this idea might account for the fossil record, it is still based upon a perspective which holds life’s development to be random, by chance. Yet it can be demonstrated that evolution, however it may have occurred, is unlikely to have been a random process.

The instructions for the plant and animal forms are contained within the genetic code. This code is complex and the amount of variation which could be involved is immense. Could this code have evolved randomly? A simple look at the figures suggests that it could not have done. If, for example, a monkey sat at a typewriter striking a key every second, how long would it take, by chance, for this monkey to create randomly an English word twelve letters long? The answer is that, by chance, it would take him almost 17 million years.32

How long would it take for this same monkey to produce, randomly, a meaningful sentence in English of 100 letters – a chain much less complex than the genetic code? The answer is that the probability is so low, the odds against it exceed in number the sum total of all the atoms in the observable universe.33 Effectively, it is impossible for a meaningful sequence of 100 symbols to be produced by chance. We must conclude that it is similarly impossible for life’s complex genetic code to have been produced by chance as the theory of evolution would require.

The astronomer Fred Hoyle, never one to suppress a pungent phrase, wrote that the chance creation of the higher forms of life is similar to the chance that ‘a tornado sweeping through a junkyard might assemble a Boeing 747’.34

If, then, the genetic code is not arrived at by a random process, then it must be arrived at by a non-random process. Where could this thought lead us?

Directed Evolution

In 1991 Wesson’s Beyond Natural Selection threw a new and powerful challenge into the arena. He dismissed the attachment to Darwinian evolution as ‘indulging the old daydream of a universe like a great clockwork’.35 Wesson points out that we cannot look at any animal in isolation. He proposes that we should consider a wider perspective: ‘organisms evolve as part of a community, that is, an ecosystem… which necessarily evolves together. One might better speak not of the origins of species but of the development of ecosystems…’36

In a truly radical move Wesson suggests that we apply the findings of Chaos Theory to evolution in order to make sense of all the staggering oddities which we see both in the fossil record and in living creatures today.

Creatures of Chaos

Chaos Theory is a means by which very complicated systems – such as evolution – might be understood. But understood as a whole, not broken up into pieces as is usually the case.

Normal physics is baffled when trying to understand and predict behaviour in such complex systems as weather patterns, the turbulence of water as it rushes down a pipe, or population growth – to give but a few examples. Chaos Theory has created a technique which is able to capture the underlying structure of such apparently random events which make up these systems; a structure which appears as a pattern.

The Chaos explanation was discovered in 1961 by Dr Edward Lorenz, a scientist working on weather prediction. He had decided to repeat a computer sequence in order to examine one particular section further. To save time, he began midway through the sequence and instead of entering the exact data, which was accurate to six decimal places, he dropped off the three last decimal places of each figure. He assumed that any change would be minimal. He ran the program fully expecting that it would replicate the first. He then wandered off to drink a coffee.

When he returned he found something quite unexpected had occurred: the result of the repeated sequence, a graph, initially looked identical to the first he had already printed, but then rapidly began to diverge; first a little, and then wildly. This rapidly escalating rate of divergence is now termed a ‘cascade to Chaos’. The very tiny, apparently insignificant, error which Dr Lorenz had introduced by dropping the final decimal places from his figures had rapidly caused a completely different result.37

Lorenz established two principles of Chaos: the first, sensitivity to initial conditions; small events can ultimately create large effects. The second, the importance of feedback from the environment. There is a constant interaction between the developing system and its surroundings, each affecting the other, backwards and forwards in an endless cycle: the system changes in a totally unpredictable way.

Chaos theorists have an eye for pattern and the patterns of chaotic systems share similarities: the same patterns seen in snowflakes are also seen in turbulent water, in heartbeat patterns, in patterns of waves breaking upon a beach. In some way nature is playing the chaos game.

In short, events which appear random turn out to have an underlying order.

The entire ecosystem within which we and all other creatures live is part of a global entity which is constantly and progressively cascading into Chaos and has done so ever since the very beginning of life. It will be seen that this idea solves the problem of the existence of millions of weird and unlikely forms of animals and plants which seem impossible to account for by Darwinian natural selection. These oddities no longer have to be seen as advantageous to be selected. The development of genetic variation chaotically cascading through the millennia can account for this incredible diversity. In comparison Darwinian natural selection seems linear, mechanistic and simple-minded.

There is a further surprising point revealed by Chaos Theory: evolutionary intent.

Because of the importance of feedback, from the environment and back again, on the creation of chaotic patterns, we can see that life is not so much helplessly modified by a one-way traffic of chance effects but actively involved in creating its own future direction.

The increase in the complexity of living creatures over the aeons is in complete accord with the theory of Chaos; a system cascading away from its starting point into unpredictable complexity. But there is more: this move towards complexity, evident in evolution, indicates that it is not random. Rather, it appears to be the expression of some deeper design: ‘Evolution can be conceived as a goal-directed process insofar as it is part of a goal-directed universe, an unfolding of potentialities somehow inherent in this cosmos.’38 And, as proof of a goal-directed universe, Wesson points to the sun and planets: they have moved naturally from a ‘fireball to solar system’. This is evidence of a progression, a cycle perhaps, where inherent potential is unfolded.

Is something seeking to express itself?

An Act of Faith

Darwin’s theory was a child of its times. Victorian man had an innate feeling of superiority over the rest of the world and Darwin appeared to have given scientific sanction to this belief.

Once the later scientists had added the discoveries of genetics to the theory, they felt that it had then become unassailable. Despite this, it remains far closer to religious faith than scientific fact. It may satisfy some scientists personally, it may give meaning to their lives, but it cannot account for the data.

A war rages over the area: some experts make an almost ideological commitment to it – like Oxford’s Professor Dawkins who is the modern equivalent of a seventeenth-century fundamentalist preacher in his fervent demand for adherence to an orthodoxy.

Under pressure, not only from the creationists, science is trying to present a united front. It is as though scientists fear that to abandon Darwin is to fall into the hands of the creationists. This is nonsense and a measure of how weak many feel their scientific explanations really are.

In the end, Darwin’s theory of evolution is a myth; like all myths it seeks to satisfy the need for understanding the origin of humanity. To that extent it may work, but that does not prove it is true.