5

CENTRAL BRITISH COLUMBIA

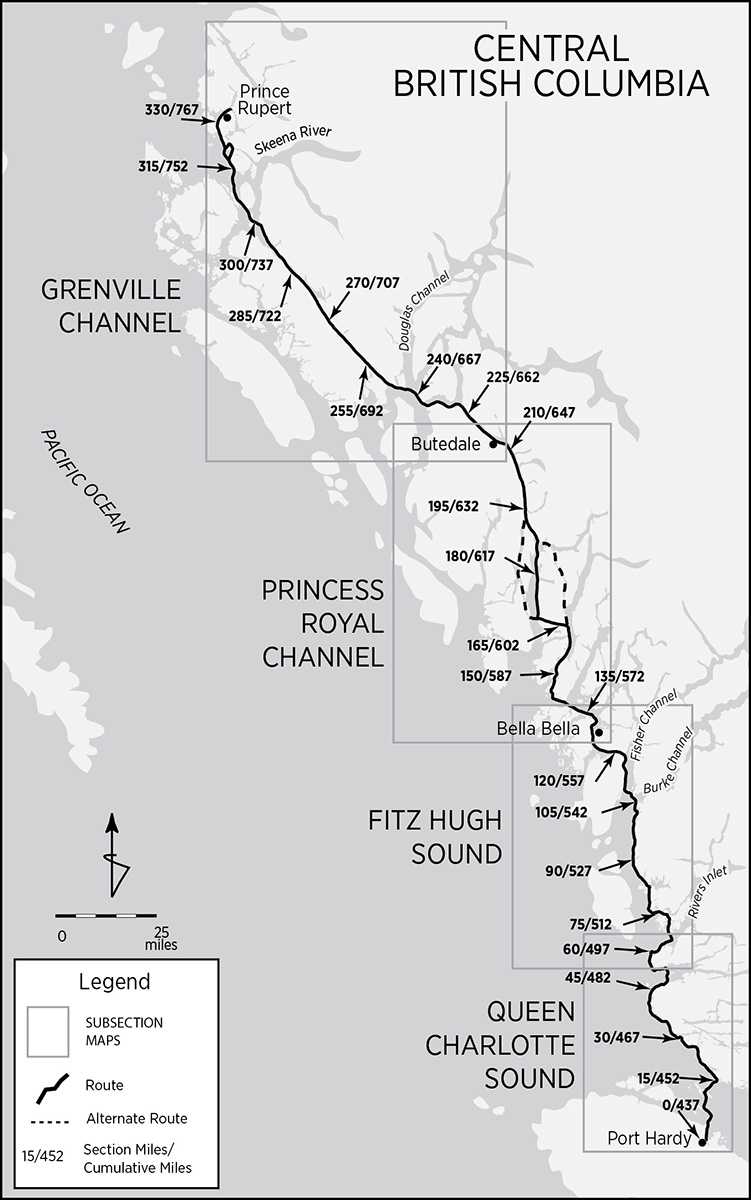

Port Hardy to Prince Rupert 331/768 miles

Port Hardy to Prince Rupert 331/768 miles

Wilderness is like first love:

beguiling, seductive, addictive;

humiliating, terrifying, sublime.

—R. H. M.

Dances with Rangers II

We’d found Louis Pasteur’s observation, that “chance favors the prepared mind,” to be spot on, and its inverse, chance overwhelms the unprepared, doubly damning. Well, chance wasn’t going to chop us up. We’d done our homework—or so we thought, until we ran into Todd, a Canadian paddler out of Prince Rupert. So intimidated was Todd by the map’s rendition of Grenville Channel that he detoured 40 miles around it into Principe Channel. Fear is contagious.

The 45-mile-long Grenville Channel, on the map, looked about as inviting as submitting to an MRI. Its laser straightness is correspondingly narrow, sometimes a scant quarter mile compressed by closely spaced, multiple contour lines with sirenic names such as Countess of Dufferin Range. Only one irregularity, Lowe Inlet, sticking out like a goiter on a giraffe, disrupted Grenville’s symmetry. Were the shores landable? Would this southeast-northwest trending canyon funnel and exacerbate prevailing blows? Would the tidal surges be navigable? None of this had crossed our minds.

We agonized and reassessed. Dignity went out the door; we offered passersby twice the going rate for large-scale charts of Grenville and begged for any scrap of information that might refute Todd’s assessment. Exactly halfway up the channel, Lowe Inlet appeared to offer a safe harbor. With a freshly re-researched, seemingly sound strategy, we decided to rely on Lowe. Prescience, however, is a flaky friend that fails randomly and often.

The run to the inlet, going with the tide and very early, proved uneventful. Lowe was all that we expected: beautiful, calm, with three open and serviceable campsites at the head where the Kuwowdah River cascades in two majestic tiers into Nettle Basin. Two classic sailboats were anchored within its protected walls. We paddled over to the first flat spot, guarded by the scant remains of a long-defunct enterprise—a scatter of old pilings. Camouflaged in the shadows was a brown bear working the shore. Not a good omen.

The second campsite, near the base of the falls, was too close to the first for safety, so we aimed for the third. However, along the way we noticed a black bear rummaging in the undergrowth at the second site. Conditions weren’t improving.

On the way to the third campsite we passed next to one of the anchored sailboats. “Looking for a place to camp?” one of the crew hailed.

“Yeah. Seen any bears over in that grassy area [the third prospect]?” we asked. He told us a grizzly had been showing up every evening to graze the young grass shoots.

All of a sudden, short of begging for deck space, our plans had been shot through with a big gaping hole. The crewmember sensed our dismay and told us to inquire at the other sailboat, a dark, ivy green schooner. A Canadian fisheries warden, busy on shore at a small, steep, thickly wooded peninsula, skippered the aptly named Grizzly Bear. We made our way over to him. Lashing on to his tender, a tiny inflatable with an outboard, we scrabbled our way toward the din of his task.

“You’re in luck today!” the warden declared expansively. Kent was tall, honest, and handsome, a very fit over-60. He was busy froeing fir shingles for a new outhouse. “I’ve just finished this warden’s cabin and you’re welcome to use it. You’re kayakers, eh? There are bears everywhere. Want to see one up close? Unload your kit and come over after dinner for tea, and Joannie [his wife] and I’ll take you over for a closer look.”

A sudden sense of relief deflated our qui vive. Kent finished shingling the outhouse roof, noted that we’d be the first to christen it, and nailed up a plaque over the cabin’s small porch: LOWE BUDGET MOTEL. Then he took his leave. “See you in a few hours.”

Kent and Joannie were instinctively self-reliant. They had homesteaded northern British Columbia’s interior forests in the early 1960s but, discovering a greater affinity for building than farming, sold the homestead. Then they did it again, from scratch. The completion of the second homestead coincided with their children’s maturity. After selling the second farm, they decided to homestead in a totally different place: the sea. Plans for the Grizzly Bear were commissioned to a naval architect. Kent and Joannie built it together. From scratch.

As planned, we went over for tea, brewed on the schooner’s four-burner wood stove, and visited. As a federal fisheries warden, Kent undertakes a variety of tasks, including fish counting. I asked him just exactly how does one go about counting fish for a ministry? He explained that he either actually walks an entire stream course or random-samples sections. As he walks—mostly in the streambed—he has a digital counter in each hand and a third, ongoing mental count, for different varieties of salmon. This informs the government about the vibrancy of the salmon stocks. I was about to ask about the uncounted varieties when instead I asked about fish-counting bear encounters.

“That’s a point of contention in this job,” he said. Totally engrossed in the count, eyes scanning the streambed for fish and footing, he’d run into more bears than he cared to recall. Luckily he was usually the more startled at the standoff, but the whole experience was a bit too unnerving. He needed someone to ride shotgun, literally. The government wasn’t about to expand the budget to include security for fish counters. So Kent hired Joannie out of his own pocket.

After tea the four of us piled into the tiny tender to get a closer look at the grizzly feeding on the young grass shoots. The little Avon was no bigger than a sheet of plywood sprouting a podium-style helm amidships. By 10 PM it was barely dusk. Kent turned the temperamental engine over four or five times before it cranked to life, and off we went to see the bear, a very large male. He was sitting on his haunches, facing the water, pulling grass out by the roots with alternate sweeps of his front paws and munching slowly and contentedly each pawful. He was oblivious—to us, our scent, the tender, the engine noise, to everything but each burst of tender young shoot flavor. He looked like the Emperor Nero at a banquet.

Kent cut the engine. The bear didn’t seem to notice. With the wind at our back, we drifted closer. I noticed that the foreshore below us had shallowed to just a few inches. Mr. Bear was now less than 50 feet away. Frankly, I was beginning to get nervous. We had no gun or pepper spray and were about to run aground at the feet of Jabba the Hutt, trusting our escape to a neurotic outboard that required foreplay. Surely one of the women would speak up.

We drifted within 40 feet of the bear. I repeated to myself that Kent knew what he was doing—after all, he was a game and fisheries warden. At 30 feet, the women still hadn’t spoken up while I was rocking from one butt cheek to the other. “Kent, we don’t want to disturb the bear, do we?” I finally stammered.

“He’s too busy eating to care. We’ll go over for a closer look at the falls.” Kent pulled the cord on the motor. It caught the third time. He turned the Avon around, actually getting even closer to the bear during the maneuver—still no reaction at 20 feet—and off we went.

At 10 to 20 feet in height (depending on the tide’s cycle) and leaning about 60°, Verney Falls was a showcase for the salmon run. Already, at this early stage of the run, you could aim your camera, shoot randomly, and be certain to catch at least one fat fish jumping. Perhaps that explained the bear density. At the height of the run, the fish are so dense that those in the water would damage your prop while those jumping in the air would certainly coldcock you. And the bears—even more by the height of the run—are so busy fishing, they ignore both each other and human observers. But by then it was getting late, so we headed back to the Grizzly Bear, our kayaks, and the snug warden’s cabin.

Native Peoples

Kent’s duties included law enforcement. He was at Lowe Inlet as a show of force. While there he was to build the “Lowe Budget Motel,” a cabin, as a permanent, seasonally manned outpost. Native poaching at Verney Falls during the spawn had become a serious problem. The warden’s presence was meant to be a deterrent.

It wasn’t the first time natives had exploited the salmon run at Verney. Right next to the Kumowdah River’s mouth, on the north side, lies a small, sandy bight. At the bight’s mouth, just where the overflow of salmon waiting to jump the falls would congregate, lies an old underwater fish weir constructed out of standing rocks. It is plainly visible at lower tides. A wide arc, several dozen feet in diameter and too regular and strategically located to be natural, it was undoubtedly further enhanced with wooden frame members. During the run, one-way mazes and falling tides would trap fish within the enclosure. The stranded salmon could then be picked manually or with double-headed harpoons. Salted and smoked, the fish would easily last a year and constituted the natives’ primary dietary staple.

Oolichan (pronounced hooligan), a small, silvery fish also known as candlefish because it is so engorged with oil that it will combust when held near a fire, was also a mainstay of the Northwest Coast economy. These were (and are) netted and rendered for their rich oil—definitely an acquired taste yet considered a great delicacy. Today, along the Nass River near the Alaskan border, the Nishga still harvest the oolichan during the great runs in March and April.

Numerous shell middens (incongruous white sand beaches) up and down the Inside Passage indicate an important reliance on shellfish, primarily clams and mussels. Halibut, those giant, one-sided bottom dwellers, were taken with large, elaborately carved, baited and weighted, wood and bone hooks. Seals, sea lions, dolphins, and sea otters were speared from canoes. The Haida, Nootka, and Makah even undertook whaling expeditions from their canoes. “Grease trails”—trading routes with interior tribes—provided a venue for the conversion of food surpluses into locally scarce, imported goods.

Archaeological evidence for Northwest Coast habitation goes back about 10,000 years. Sites at both extreme ends, at the Dalles, Oregon, and at Ground Hog Bay village, Glacier Bay, Alaska, have been carbon-dated to 8,000 BC. Namu, smack in the middle of the Inside Passage, has also rendered three dates clustered around 8,000 BC. Bear Cove, next to Port Hardy (where the ferry terminal is located), and Lawn Point, on the east coast of Graham Island in the Queen Charlottes, yield dates of similar antiquity.

Prior to the arrival of the Europeans, there was no wilderness. All the land along the Inside Passage was accounted for, claimed, and geographically subdivided into well-defined political entities with attendant property rights. White traders were annoyed to discover that even the taking of firewood or fresh water required payment to someone. These entities were independent of each other and had a “capital” village, with a contiguous, resource-rich rural hinterland. Within each village-state, called a qwan by the Tlingit, settlement patterns followed an annual cycle determined by salmon runs, seasonal harvests, and the hunt. During winter, the population of each qwan would congregate in the principal village, while in summer, smaller groups would disperse to seasonal camps to exploit cyclical resources. Permanent winter villages were located in sheltered bays, inlets, and river mouths in close proximity to good fishing and where canoes could safely land.

These village-states lacked any tribal or national meta-organization other than constantly shifting military alliances and commercial arrangements buttressed by infrequent ceremonial get-togethers, linguistic affinities, and shared customs. Villages consisted of warehouse-scale longhouses—rectangular gabled buildings of massive post-and-beam construction sheathed with cedar planks. Longhouses were built next to each other facing the beach. Some particularly large towns, however, would have a second row of longhouses behind the first. One exceptionally large qwan, Chilkat, at the upper end of Lynn Canal, had four large villages. The largest of these, Klukwan, had 65 houses and about 600 residents. In 1854, British naval officer W. C. Grant described a typical Vancouver Island Indian village:

No pigstye could present a more filthy aspect than that afforded by the exterior of an Indian Village. . . . They are generally placed on a high bank so as to be difficult of access to an attacking party, and their position is not unfrequently chosen (whether by chance or from taste) in the most picturesque sites. . . . A few . . . oblong holes or apertures in the palisades (generally not above three feet high) constitute their means of egress and ingress. They seldom move about much on terra firma, but after creeping out of their holes at once launch their canoes and embark therein. . . . A pile of cockle shells, oyster shells, fish bones, pieces of putrid meat, old mats, pieces of rag, and dirt and filth of every description (the accumulation of generations) is seen in the front of every village. Half-starved curs, cowardly and snappish, prowl about, occasionally howling. And the savage himself, notwithstanding his constant exposure to the weather, is but a moving mass covered with vermin of every description.

Generally speaking, when not engaged in fishing, they pass the greater portion of their time in a sort of torpid state, lying beside their fires. The only people to be seen outside are a few old women cleaning their wool or making baskets. Sometimes a group of determined gamblers are visible rattling their sticks, and occasionally some industrious old fellow mending his canoe . . . any unusual sound will bring the whole crew out to gaze. . . . They may wrap their blankets around them, and then sit down on their haunches in a position peculiar to themselves. They are doubled up into the smallest possible compass, with their chin resting on their knees, and they look like so many frogs crouched on the dunghill aforesaid.

Political power was vested in the chief of each village-state. The chief’s ascendancy was determined by a combination of hereditary rank (emphasized in the north) and wealth (more important farther south). A variety of inherited and merited ranks, from chief down to slave, stratified society, which itself was organized, in descending order, along moieties, clans, extended families, and nuclear families.

Moieties are the two equal halves into which all Northwest Coast societies are divided. These are formally named—the Haida, for example, were either “Raven” or “Eagle”—and were represented by totemic or heraldic crests. Moieties are exogamous—for example, a Raven must never marry another Raven. To this day, membership in a moiety generates the same sort of loyalty, enthusiasm, and friendly rivalry that identification with a baseball team often does in New York. Family lineage was reckoned matrilineally, patrilineally, or bilaterally, depending on local custom. Clans are lineages (hyperextended families) whose members all trace their origin to a common ancestor, much like the Campbells and McDonalds of Scots Highland fame. These too are formally named and exogamous—a form of marriage restriction that inhibits incest. Abortion and parricide kept nuclear families small, as Mr. Grant again elaborates:

The natural duration of life among the savages is not long, seldom exceeding 50 years. Indeed, a gray-haired man is very rarely seen. This may be partly accounted for by the horrible custom (universally prevalent) of the sons and relatives killing their parents when he is no longer able to support himself. . . . Sometimes the wretches commit this parricide of their own accord unquestioned, but generally a council is held on the subject at which the . . . medicine-man presides. Should they decide that the further existence of the old man is not for the benefit of the tribe, the judges at once carry their own sentence into execution. Death is produced by strangulation by means of a cord of hemp or sea weed.

Not less horrible is the custom, very prevalent among the women, of endeavoring to extinguish life in the womb. From this and other causes premature births occur with great frequency. The native Indian woman seldom becomes the mother of more than two, and very rarely indeed of more than three little savages or savagesses. Whilst on the other hand, the half-bred woman is almost invariably extremely prolific.

These “savages” could be an intimidating encounter. They were tall (5 feet, 8 inches average in the north) and lean with stocky chests and muscular shoulders topped with broad heads and broad faces elaborately mutilated and made up either to attract or repel. When young, a male’s nasal septum was pierced and a ring or length of bone inserted. Small holes around the outer circumference of the ear displayed bits of wool or feathers, while ornaments of shell, stone, or teeth hung from the lobes. Facial hair, already light, was plucked, while the coiffure, parted in the middle and impregnated with grease, hung loose over the neck. In addition, women pierced their lower lips to display labrets sometimes spanning 4 inches. Tattoos and elaborate facial paintings rendered with a pigmented seal oil base completed the arrangement.

Like the British, the Northwest Coast Indians named their houses. The names were not humble or subtle: House Which Thunder Rolls Across, House Other Chiefs Peer at from a Distance, or the unforgettable House People Are Ashamed to Look at as It Is So Overpoweringly Great. Inside the longhouses families would stake out and partition portions with their paraphernalia. A central cooking area and smoke hole served all the residents. Plank flooring lined the whole structure, including a recessed lower level somewhere near the center. Northern longhouses averaged 3,000 square feet; in the south, bighouses might run to 30,000 square feet. Fifty to 200 individuals, usually members of a single clan, inhabited each dwelling. While spring, summer, and fall were taken up with economic activity, winter, with its constant precipitation, provided a time for creative indulgence and consumption. Elaborate theatrical productions, based on religious themes and employing smoke, trapdoors, and crawl spaces for heightened dramatic effect, warded off cabin fever. While you can still visit a longhouse and witness some of these reenactments—for example, at Blake Island in Puget Sound—you’ll never participate in a potlatch.

Extravagant parties—actually orgies of conspicuous consumption—with many subtle undercurrents, potlatches were held to celebrate a birth or marriage; commemorate the dead; settle a property dispute; soothe hurt feelings or humiliate a rival; formalize a succession line; dedicate a new longhouse; or punctuate any important event. The Northwest Coast Indians seem to have fully understood that it is better to give than to receive, and though some income redistribution ensued (important in its own right), the social ascendancy of the host was the primary objective of any potlatch.

At the previously mentioned potlatch hosted by Dan Cranmer of Alert Bay in 1921, the chief entertained 300 guests and divided his vast wealth among them: more than 450 ceremonial items, including masks, dance capes, and coppers (shieldlike symbols of wealth), 24 canoes, billiard tables, musical instruments, sewing machines, motorboats, 400 Hudson’s Bay blankets, 1,000 sacks of flour, and food and drink commensurate with the occasion. Some feast throwers achieved a truly zen state of disdain for material possessions by actually burning—instead of giving away—assets, including killing (prior to European contact) hapless slaves. Potlatches could last for days and leave the host materially destitute (albeit some reimbursement was inevitable in the course of reciprocal potlatches) but inestimably prosperous in repute and radiant in cynosure. Such was the gravity of the enterprise that individuals would seldom host more than two potlatches in a lifetime.

Scandalized by the wanton destruction of property, some of it contributed as relief or compensation for past injustices, and under the understandable impression that penury would ensue, thereby exacerbating a vicious feedback cycle, the British Columbian government outlawed the feasts in 1884. By the time potlatches were again legalized in 1951, the custom had waned.

Perhaps the most evocative artifact of Northwest Coast native traditions is the totem pole. Although present prior to the arrival of Europeans, totem poles were smaller, less elaborate, and not as ubiquitous. In spite of the various depredations suffered as a consequence of contact, a minor renaissance ensued with the tremendous increase in trade and exchange of ideas. Metal knives and soft western red cedar, coupled with artistic vision and acumen and leisure time, gave rise to the totem pole efflorescence that continues to this day.

Traditional totem poles rarely exceeded 60 feet and were usually incorporated into the design of a house as entry posts. They were totemic in intent—that is, they depicted a mystical relationship between a family or individual and a totem, an animal or plant with a particular significance to a family’s lineage. Much like a family emblem or heraldic crest, it served as a symbol of family pride and a historical pictograph depicting its entire ancestral history. Few of these poles remain today, as most cedar logs decay within 60 to 80 years, though some in the Queen Charlottes are over 100 years old.

After contact, totem pole iconography burst its bounds. The Nisga’a of the Tsimishian led the way. Freestanding welcome poles at the waterfront invited visitors; mortuary poles, implanted with a box of the honored individual’s decomposed remains, honored a significant person; memorial poles, erected either to commemorate a deceased chief’s accomplishments or, like the apocryphal Lincoln totem pole, to commemorate Alaska’s purchase by the United States, marked a peoples’ rites of passage. Shame poles, carved with upside-down figures, were temporary fixtures and are found only in museums today. Closely related are ridicule poles, T-shaped with self-satisfied buffoonish carvings along the top, intended to deprecate an individual’s actions or aspirations.

New totem poles are rarely constructed for traditional or neotraditional purposes, but are instead commissioned as art for college campuses, museums, public buildings, the private market, and as public art to honor the First Nations and their outstanding artistry.

Consider for a moment the above ornament, which separates minor thematic transitions in this book. Deceptively simple, understatedly elegant, and soothing in its perfection, what function does it serve? Just exactly what is it? In this context, it’s an elaborate, overgrown punctuation mark, a period, reminiscent of the opening capitals of medieval manuscripts. Stylistically, there is nothing quite like it in the world. It is unambiguously and quintessentially a Northwest Coast Indian art motif. Jose Cardero, expedition artist for Galiano and Valdes on the Sutil and Mexicana in 1789, noticed it. The motif crops up in several of his sketches.

It is difficult to pinpoint the essence of a motif, as each of its component parts can vary so widely. In its many renditions, it is the fundamental design unit of all Northwest Coast Indian art. Focusing on their perimeter shape, Franz Boas, encyclopedic chronicler of North America’s vanishing aborigines at the turn of the twentieth century, called them “eye designs.” Bill Holm, a leading authority on Northwest Coast Indian art, calls them “ovoids.” The ovoid typically frames some dismembered, stylized body part such as an eye, a claw, the front teeth of a beaver, or the dorsal fin of a killer whale.

Even their shape can vary to rounder, more trapezoidal, rhomboid, or even parenthetical. Topologically, however, all variations remain equivalent. Perhaps these ovoids are akin to the modern plastic grocery bag, varying in shape and size according to its contents (always of a certain provenance) but ever identifiable and never confused with, say, a suitcase. On a decorated item such as a blanket, oolichan dish, chest, or bentwood box, ovoids tend to fill the entire surface area being decorated, leaving little or no blank background.

What muse inspired such symmetrical and pervasive artistic abstractions uniformly throughout the Northwest Coast? Jonathan Raban, in Passage to Juneau, speculates incisively that:

author with water ovoids

The maritime art of these mostly anonymous Kwakiutl, Haida, and Tsishimian craftsmen appeared to me to grow directly from their observation of the play of light on the sea. . . . I saw a water-hauntedness in almost every piece. . . . The simplest way of retrieving order from chaos is to hold a mirror to it . . . [like a] kaleidoscope. . . . In the sheltered inlets of the Northwest, the Indians faced constant daily evidence of the mirror of the sea as it doubled and patterned their untidy world. . . . Sometimes, especially in the morning, the water of the inlets is as still as a pool of maple syrup, its surface tension unblemished by wind or tide: then it holds a reflection with eerie fidelity, with no visible edge or fold along the waterline.

Raban is on to something. The ovoids are the spitting image of the variations in sea-surface tension observed from the bow of a canoe or the cockpit of a kayak. Note the water surface patterns on the accompanying photograph. Rendered upon a blank canvas, they evoke Antonio Gaudi’s artistic philosophy of abstractly replicating patterns found in nature. Inside the ovoids, the designs, sometimes stylized vestiges of body parts or abstract renditions, are a collage of reflected images.

Unlike many other parts of Canada, in British Columbia native groups never surrendered ownership of their land. They still lay claim to much of the province. In 1992, the federal and BC provincial governments, agreed to negotiate a comprehensive settlement to extant land claims with the province’s First Nations. As of 2012, only the Tla’amin, Tsawwassen, Maa-nulth, Yale, and Nisga’a have settled. The remaining 40 percent of the province’s 130,000 natives have boycotted the process, opting to use the courts to uphold their rights. The impasse has not significantly affected day-to-day life or deterred investment.

Natural History

To the Kwakiutl, Nuxalk, Heiltsuk, Nisga’a, and Haida, central British Columbia was patria, a home exuberant with people, settlements, resources, and the quotidian activities associated with making a living. To visitors it is a wilderness. And what a glorious wilderness it is: sparsely populated (now), teeming with wildlife, and seemingly—if not actually—remote from the centers of western civilization, a region that induces awe, introspection, contemplation, and spiritual renewal. Chances are it may remain this way. In 2001 the British Columbia government approved, in principle, the new 1,200-square-mile Spirit Bear Park, including Campania, Swindle, and Princess Royal islands, along with much of the adjacent mainland coast. In conjunction with the Fjordland and Kitlope protected areas, about 2,500 square miles are now permanently protected. A further 3,000 square miles have had logging deferred.

Central British Columbia is the most uninhabited section of the entire Inside Passage. Between Port Hardy and the Prince Rupert metropolitan area, along the waterway, there are very few towns: Bella Bella (Waglisla), Shearwater, Klemtu, Hartley Bay, Kitkatla, Ocean Falls, and Oona River. Some have fewer than 50 people. Not far away, the deep inlets of the interior verges cloister Bella Coola, Kitimat, Hagensborg, and Kimsquit. A handful of smaller outposts round out the settlements that together comprise a population of fewer than 4,000 residents, mostly native. Numerous smaller redoubts—fly-in fish camps, abandoned canneries with colorful caretakers, manned lighthouses, ad hoc logging camps, overgrown outposts, and villages forgotten by all but a few, and even transient agglomerations of anchorage seekers—round out the settlement pattern. Even radio contact is sparse. Be fully self-sufficient. Any sort of rescue operation can take days instead of hours. Proper preparation can be the difference between confident self-reliance and grim survival.

Campsites are often limited to toeholds, many carved by previous itinerants. The coastal ranges dominate the littoral topography even more so than in southern British Columbia. Bare rock abounds, and not just because treeline is lowering. This is a steep and young landscape, not the best conditions for soil formation. In sharp contrast, extensive white sand beaches trim the Cape Caution surrounds like lace edging. Exposed to the churn of the breaking surf, much of this section of coast, over time, has been ground into sand by the Pacific swell.

Precipitation, in all its myriad forms, abounds. Fog lingers longer. Mists become drizzles, drizzles turn into showers, and rain can last for days. Snow arrives earlier and overstays its welcome. During summer, temperatures rarely hit 90°. Though no one would nickname central British Columbia “Sunshine Coast,” it can be balmy, although seldom for more than one or two days at a time.

Ursus arctos horribilis, the brown bear, thrives here, especially where major river channels and inlets connect his home range in the mountains with the sea. You will encounter him. After landing at a likely campsite in Smith Inlet, we noticed what looked like a beaver swimming straight for us from an outlying island. The scale was deceptive; it was a grizzly’s head. We tripped, fell, bumbled into each other, and even managed to rip open and spill our wine-in-a-box during the mad scramble to stuff our gear back into the boats and disappear. Black bears (Ursus americanus) are downright common. Along the more protected passages you’ll run into more than one bear per day, any time of day, sometimes even at camp, where he’ll run into you. However, you’re not likely to see a spirit bear (Ursus americanus kermodei), namesake of the proposed new park. A rare subspecies, only about a hundred survive on the islands and mainland north of Bella Bella, in an area centered around Princess Royal Island. Although technically a black bear, the Kermode’s color ranges from snowy white to café au lait. It is not an albino but rather an occasional manifestation of a recessive—albeit persistent—gene that perhaps offered an evolutionary advantage during the last ice age.

Where there are bears, there are salmon. The seasonal runs in Smith and Rivers Inlets attract not only grizzlies from the high interior but also human subsistence, commercial, and sportfishermen. These are world-renowned salmon fishing waters. Both inlets are dotted with seasonal, fly-in, strictly angling resorts, some floating on reconditioned barges.

And salmon also attract orcas. Driven to Brown Island in Smith Inlet by the swimming grizzly not an hour earlier, we were called on by a pod of killer whales. Each whale, in turn, came over and scratched at a shoreside rock outcrop not 50 feet from our tent. A few days later in Whale Channel, three orcas, led by a magnificent bull with a disproportionately large and eccentrically angled dorsal fin, headed directly for us, nipping in and out from the shore, at an alarming rate. Windmilling for land, I suggested that Tina hold her position for some good photos. She reached shore before I did.

Wolves, too, are common. On one isolated beach, an adolescent wolf played tag with a rambunctious raven. And play it definitely was. This wolf wasn’t looking to eat crow. Down would swoop the bird while, in response, the pup would run, splay his forelegs, and spin around for another pass. Back and forth along that quarter-mile stretch, the free-form waltz added a playful touch to our lunch.

Besides the nearly impenetrable Coastal Ranges, two other important obstacles bracket this bit of coast to maintain it in such splendid isolation.

To the north lies the international boundary with Alaska. At both ends, wide corridors—Dixon Entrance at the north, and Queen Charlotte Sound at the south—connect Inside to Outside. The exposed coastal areas, in the American vernacular, “separate the men from the boys.” Casual cruisers cross these unprotected gaps only with due diligence and prudent haste. At both locales, Pacific sea states, unhindered by fringing islands, converge on the exposed shore and, in periods of inclement weather, let loose all hell. At the very minimum, in the best of conditions, Pacific swell will waltz your boat and tattoo the shore. Cape Caution, so christened by Vancouver after his own close call and observations, is no place for kayaks to linger. Monitor well the forecast, inventory all possible sanctuaries, avoid surf landings, crank out the miles, and hie for more protected waters.

The Route: Overview

This section of the Inside Passage is divided into four more or less equal portions: Queen Charlotte Sound, Fitz Hugh Sound, Princess Royal Channel, and Grenville Channel. Up here the Cascadia Marine Trail is purely a dream held together by a vision, while the British Columbia Marine Trail Association’s hand has touched only lightly, if at all. Fortunately both the route and the logistics are relatively straightforward, though there are two alternates to the main route about halfway up, near Klemtu. All three choices diverge and rejoin near the same spots; each is about 30 miles in length and is described at the appropriate point along the main route.

Queen Charlotte Sound has been derisively nicknamed the Queen’s Pond in an ironic reference to its lack of tranquility. The first 50 miles of this 335-mile portion, the crossing of Queen Charlotte Sound and the exposed coastline around Cape Caution, is the crux. That knowledge and the preparation for imminent total performance can create a hollow anguish in the gut, the result of commitment and resolution laced with fear. My high school football coach used to call it “the big eye.” Use it to your advantage. It won’t help that the boats are probably full to the brim, making them sluggish and unwieldy.

From the protected backside of Vancouver Island, the route immediately plunges across Queen Charlotte Sound over to the mainland via a series of opportunely spaced island groups. These stepping-stones reduce the crossing to a series of short hops, none greater than 2 miles. The next 35 miles to Smith Inlet are the crux de la crux. Luckily there are plenty of protected harbors along the way. Once in Smith you have some protection, but you’re not fully inside yet. Around Kelp Head, at Rivers Inlet, the route enters Fitz Hugh Sound and for the remaining 285 miles uses protected channels to wend its way to Alaska.

Heading north up Fitz Hugh to Bella Bella/Shearwater, the route marches in step with the ferries, cruise ships, and cargo bearers that ply the Inside Passage. Beyond Seaforth Channel, we part company with the masses. While the shipping route goes up Finlayson Channel, the kayak route cuts up Mathieson Channel. At Jackson Passage, the two alternate routes diverge. Following the route-setting algorithm outlined in Chapter 2 (shortness and sweetness), the main route, after Jackson Passage, goes up Finlayson Channel to Hiekish Narrows, where it rejoins the main traffic route and the two alternates at Princess Royal Channel’s Graham Reach.

Princess Royal Channel is deceptive. It is this portion’s secondary crux. Finlayson and Tolmie channels innocently funnel all traffic into this seemingly welcoming and protected watercourse. But Princess Royal’s embrace also funnels and then constricts wind and tide within its plunging rock walls. Conditions can deteriorate quickly, and landing spots—especially north of Butedale—are nearly nonexistent. Problem bears trapped near Terrace and Kitimat are relocated along the mainland between Griffin Pass and Khutse Inlet in Graham Reach.

After Princess Royal, Grenville Channel looks like a Royal redux, only longer and narrower. Not a welcome prospect—it has deterred more than a few Inside Passage paddlers. Unlike Princess Royal, however, which becomes steeper as you progress, Grenville eases, never becomes impossibly steep, and the critical distances, if properly coordinated with the current and winds, are quite manageable.

Beyond Grenville, the route dodges the Skeena River’s mouth and all the obstacles that a major river’s delta holds—the Skeena is the largest river in British Columbia north of the Fraser—and heads up to Prince Rupert alongside the big boats. There you can catch the BC ferry back to Port Hardy.

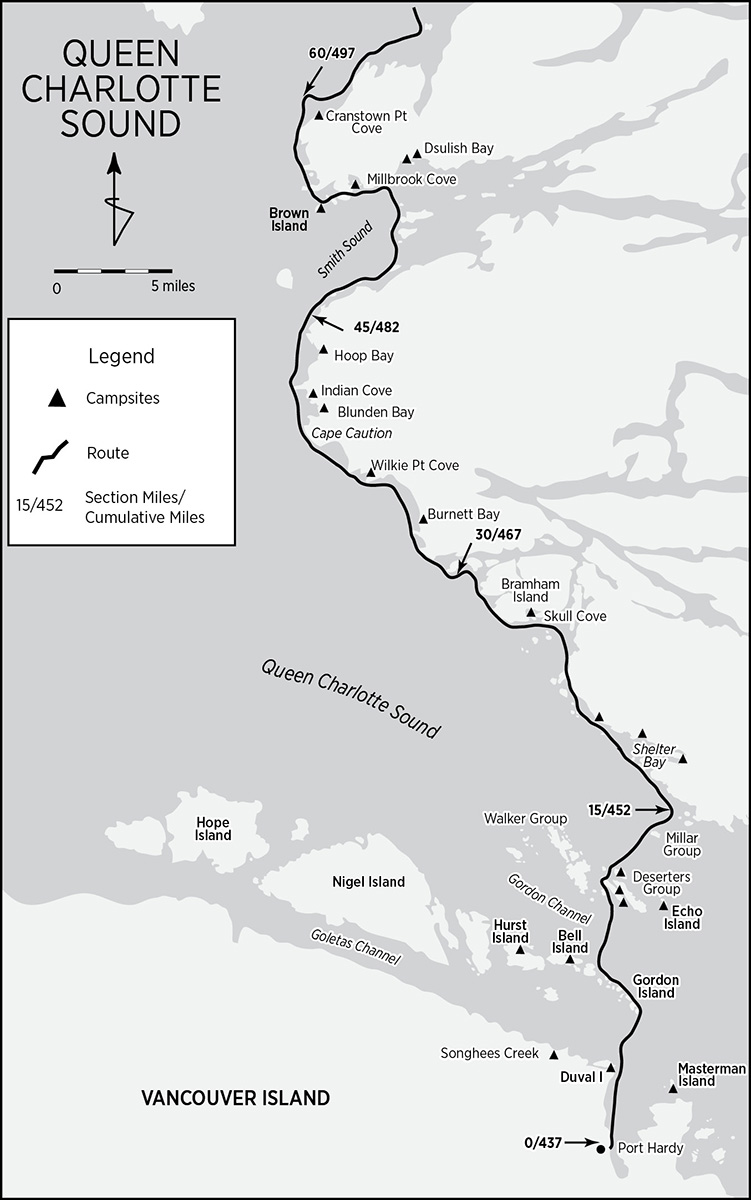

Queen Charlotte Sound: Port Hardy (mile 0/437) to Rivers Inlet (mile 60/497)

Queen Charlotte Sound: Port Hardy (mile 0/437) to Rivers Inlet (mile 60/497)

If you’ve driven up, Port Hardy has at least three likely launch sites with nearby long-term vehicle parking, and a possible fourth. The closest to the Gordon Group Islands is the Scotia Bay RV Campground just out of town and at the north end of Hardy Bay. Access is north off Market Street/Park Drive and straight through the Tsulquate Reserve.

Centrally located are two possibilities, the public dock and Carrot/Tsulquate Park. In spite of all the hustle and bustle, Quarterdeck, the public dock and marina close to the center of town, is an excellent launch site, though you must be efficient so as not to congest the boat ramp. Here, and at the Prince Rupert and then the Port Hardy ferry terminals, a set of kayak wheels might be handy but are not essential. The public dock includes public pay parking. The address is 6600 Hardy Bay Road. It offers several advantages, including public restrooms, showers, a launch ramp, and a central location. For a more relaxed kit-up and launch, head for the public beaches of Carrot and Tsulquate Parks, with their PORT HARDY: MINING, FISHING & LOGGING carved wooden sign. The park complex is near the north end of town, just north of Government Wharf. We parked and got ready in the open area just north of and adjacent to the house on the north side of the park. Debbie Erickson, in Kayak Routes of the Pacific Northwest, suggests checking with the Northshore Inn (corner of Market Street and Highway 19), less than a two-minute walk away, for parking.

At the bottom of Hardy Bay is the Sunny Sanctuary Campground (250-949-6753) near the south end of town, at 8080 Goodspeed Road, just off the trans-island highway. Although located on the water, Sunny Sanctuary is, unfortunately, not the best spot to launch, unless you’re willing to time the tides exactly. The estuary inundates only briefly at high tide, and there’s a bit of a carry. Additionally, the exposed mud flats make for a messy and buggy launch. Sunny Sanctuary charges about $50 Canadian for vehicle storage. If launching from Tsulquate Park or the public docks but opting to store your vehicle at Sunny Sanctuary, before calling for a taxi, walking, or hitchhiking, ask the campground host for a ride. The owners are very helpful, and if time and pocketbook permit they can be quite accommodating.

The Queen Charlotte Sound portion of central British Columbia focuses on the corridor where the open Pacific funnels into and out of Queen Charlotte Strait. The water is fresh, clear, cold, and fast. It has to be to get all the way behind Vancouver Island, in and out, twice a day. And it accelerates as the entry narrows and is further constricted by the many little island groups at the mouth of the strait. Tidal exchanges carry an astounding volume of nutrients that sustain dense invertebrate populations. Conspicuous in the 100-foot-visibility water are anemones and sea stars of all sizes and colors, often piled in promiscuous mounds of teeming activity. Keep an eye below and another ahead.

Knowledge, good planning, speed, and endurance are essential to crossing Queen Charlotte Strait, heading up Queen Charlotte Sound, and reaching fully protected waters again. As when eating an elephant, each morsel is cut, chewed, and digested one bite at a time. If you don’t already have them, invest a few bucks on Canadian Hydrographic detail charts #3548 and #3549 so that each island and passage between Port Hardy and the mainland are crystal clear. Get a reliable weather report, set a date, and get an early start to take advantage of the best conditions.

Between Port Hardy and Duval Point is a 2-mile warm-up paddle to the mouth of Hardy Bay. Duval Point is on Duval Island; Strawberry Pass (mile 2/439) separates Duval from Vancouver Island. Inside is a scenic little channel with a fishing lodge and campsite—in case of any last-minute doubts. Another fine campsite just before committing to the crossing is Songhees Creek (mile 2/439), 2 miles west up the coast.

Two miles across Goletas Channel lie the Gordon Islands, first stepping-stones in a series of many. The Tatnall Reefs and Nahwitti Bar secretly protect Goletas Channel from Pacific swells. One of four subsidiary channels that lead from Queen Charlotte Strait to Queen Charlotte Sound, Goletas Channel’s currents, when present, are moderate and laminar. Head for the eastern end of the Gordon Group, near Doyle Island, turn the corner, and head up the north shore of the group. Many landing spots and a small cove midway up the north side of Doyle offer respite. Doyle and Heard, as well as upcoming Hurst, all have fish farms. As you course northwest toward Heard Island, study conditions in Gordon Channel in anticipation of the crossing to the Deserters Group, and keep an eye out for the Port Hardy-Prince Rupert Ferry.

God’s Pocket Provincial Marine Park: Just to the west-nothwest of Heard Island lies God’s Pocket Provincial Marine Park. The park showcases some of the spectacular invertebrate biomass along the Queen Charlotte Strait littoral and so is a popular diving destination. The park includes Bell Island (mile 8/445 and about a mile off-route) and Hurst Island (mile 8/445 and about 3 miles off-route). Traditionally, God’s Pocket, a small cove on the west side of Hurst Island, has been a sailor’s haven for the crossing of the strait and has a resort. Bell has a remarkable campsite in a protected little cove hidden behind the Lucan Islands. The campsite itself is on top of a shell midden about 16 feet higher than the beach. Minimize your impact; middens are archaeological sites.

unnamed cove, gordon islands

Harlequin Bay, deeply indenting the east side of Hurst Island (mile 8/445), has a campsite at its head. The long beach dries at low tide, so time your arrival on the higher part of the tide. Water is seasonally available at various sources. A trail crosses the island to the resort, where water is certainly available. Doug Alderson, in Sea Kayak Around Vancouver Island, also mentions campsites on Balaklava Island and Loquilla Cove.

Gordon Channel, too, in spite of its width, is somewhat protected both by flanking Nigei Island and an underwater sill that runs from Bell to Staples Island. Currents are not a concern. From Heard Island, nip across another 2 miles to the congested southern edge of the Deserters Group and into Shelter Passage. The Deserters are replete with protected bights, accessible landings, and a fish farm off the west-central coast of Wishart Island (mile 12/449). Wishart has a couple of nice campsites, one on the tombolo off its south end and another on the east side opposite Deserters Island.

Go around either end of McLoud Island (mile 13/450), check the tide tables, and position yourself for the 1.5-mile crossing of Ripple Passage. Tidal streams, in springs under full current, can attain 4 knots, with rips and eddies in places. If the tide is flooding, head straight for the Millar Group; if it’s ebbing, work your way down the Deserters Island coast and plunge across near Echo Island. If you need to wait, McLoud has a campsite on its north shore and Echo has one on its south shore. The Millars, like the other groups, are strikingly beautiful and accessible. Most are rounded, bare rock with sparse vegetation reminiscent of a Japanese zen garden.

Richards Channel separates the Millar Group from the Jeanette Islands adjacent to the mainland. Ghost Island splits Richards Channel’s 1-mile width. At the narrowest point at the worst of times, currents can reach 3 knots. Once across, take a minute to savor the accomplishment, but if time and conditions allow, crank out the miles.

Shelter Bay (mile 18/455) is the first best camping opportunity on the mainland, with multiple tent sites in the trees and a freshwater stream. The cove east of Westcott Point has a surf-free white sand beach just behind the brace of islands protecting the foreshore. A tad off-route is another campsite at the end of the south branch in the east end of Shelter Bay.

Two miles on, the Southgate Island Group proffers some protection. There is a nice campsite on the mainland in the semi-lagoon behind Arm Island (mile 20/457). Log booms are often stored behind Knight Island.

For a few more miles along, in the vicinity of Bramham Island, the coastal topography affords some nooks and crannies before the starkly exposed shores of the Cape Caution region. Unfortunately, we did not linger long in this area, taking advantage of good conditions to round Cape Caution into Smith Inlet. The Coast Range’s pediment here is extensive and low lying, creating a landing- and campsite-friendly area, barring surf activity. But even this last negative aspect has its positive side: sandy beaches with broad foreshores.

The Deloraine Islands and Murray Labyrinth are replete with low islands and foreshores, implying many camping possibilities. Gradual foreshores are good indicators of shallow waters offshore, and this happens to be the case here, making for good shellfish habitat. Aboriginal shell middens abound. Inside Skull Cove (mile 26/463) there is a protected camp developed in the past as a whale-watching site with boardwalks connecting small structures. The entire easternmost island is a shell midden!

Miles Inlet (mile 28/465), halfway up Bramham Island, is the last secure port south of Cape Caution. It is popular with small cruisers. With a following sea, entry into its 75-foot channel can be a bit unnerving. Old-growth cedars line the banks. Again, my apologies: we did not explore it. With a little bit of luck, you might find a campsite, if needed, within.

Slingsby Channel and the Fox Islands are two other spots I know nothing about (as good a reason as any to write about them). Because they face nearly due west, swells from that direction are funneled and compressed at the entrance. Not a good spot to seek shelter. Furthermore, tidal floods can reach 7 knots and ebbs 9 knots.

Heading north past the Fox Islands and Lascelles Point, the relatively featureless Cape Caution headland dominates. South of the cape a series of broad and shallow bays and coves with white sandy beaches beckon: Burnett, Wilkie, and Silvester. The natives knew Burnett Bay as “Place to Dance on Beach.” Back in 1985, Randel Washburne built a small cabin in Burnett Bay specifically for itinerant paddlers. Susan Conrad, in her book Inside: One Woman’s Journey through the Inside Passage, reports that the cabin, “a magical and mystical” place, was still in decent shape in 2015. The campsite (mile 33/470) is just around Bremner Point in a nook that’s usually protected from the surf. But beware, these bays are pounded by surf, and the only dance you might indulge in is the dance of success and survival at landing. More than one kayak expedition has been tested in these waters. The cove just north of Wilkie Point (mile 36/473), due to its horizontal depth and protective fore island (extending underwater as a shelf), does, however, offer a somewhat protected landing on the sandy beach, with pleasant camping and a stream nearby.

Cape Caution: Known to the native people as “Forehead,” Cape Caution (mile 39/476) was so named by Vancouver after nearly losing the Discovery in the vicinity. Between Slingsby Channel and Smith Sound lie nearly 20 miles of bluntly exposed waterfront capped by the glabella of Cape Caution. The full might of the north Pacific can and does crash into this brow. Confused sea conditions, caused by reflected swells, ebb tides, and freshwater runoff flowing due west, and further exacerbated by shallow water directly off the cape, extend for at least a mile seaward. Even the bonsai-like vegetation, like kinesic meteorological records, reflects the violence. A lighthouse crowns the cape. North of it, safe harbors become more common, at least for the kayaker.

Rounding Cape Caution requires some strategy. From Wilkie Point Cove to the first protected inlet north of the cape lie 6 choppy miles or a 90-minute to two-hour determined paddle. Stay well offshore. One mile west of the cape draws only 7 fathoms (42 feet) of depth, while within a half mile, depth sounds at only 29 feet. Such shallows affect swell. With accompanying clapotis, be prepared for a turbulent ride. Not to belabor the point, but get an early start so as to pass the cape during the morning hours. Monitor both the evening and daybreak weather forecasts. If you have a VHF radio, you can get a personalized, custom, up-to-the-minute weather and sea state report from the Egg Island meteorological station located 6 miles northwest of the cape and about 2.5 miles off the headland. Though conventional reports always include the Egg Island data, the lightkeepers volunteer updated weather information on Channels 82A and 09 with the call sign “Egg Yolk.”

Once past Cape Caution, three or four small bays and coves offer some protection to the desperate paddler. The north and south extremities of Blunden Bay (mile 41/478), looking like the pincers of a giant crab’s claw, extend some shelter with attendant camping on the sandy beaches. Adjacent Indian Cove—named for its popularity as a rendezvous for natives traveling between Fitz Hugh and Queen Charlotte Sounds—is a bit more protected but has a narrower entrance.

North of Neck Ness, Alexandra Passage protects the southern approach to Smith Sound. At first glance, Alexandra Passage seems an imaginary designation. However, Hoop Reef, guarding Hoop Bay (mile 43/480), marks the start of a series of reefs and offshore islands that create Alexandra Passage. Slip behind the reefs for access to the bay and good, sandy camping. Protection Cove, close east of Milthorp Point, is also good for kayaks. Round Macnicol Point, and by the time you reach Jones Cove you’ll have entered Smith Sound and will be past the Cape Caution difficulties.

Smith Sound: Coast along the shore to the Search Islands and island-hop across Smith Sound’s opening to the Barrier Group and on to Smith’s north shore. Dsulish Bay (mile 53/490), a tad off course eastward, has two good campsites with sandy beaches. The Millbrook Cove area (mile 54/491) has a few camp prospects, some on shell middens (which, if at all possible, ought to be avoided due to archaeological concerns). Beware camping on the mainland, as this is prime grizzly country. If possible, opt for any one of the numerous islands dotting the sound. Our favorite was Brown Island (mile 56/493) at the northern, outermost extremity of Smith Sound.

Brown is an excellent spot for an isolated layover day after the rigors of Cape Caution. Far enough from the mainland to discourage curious bears, its protected east side has a blindingly white sand beach subdivided by rock outcrops and intertidal shelves into individual campsites. The views east up the sound and onward north are incomparable, photogenic, and transcendent. Strategically scattered drift logs make for convenient and aesthetic clotheslines and kitchen counters. A complete circumambulation of the island is a half day well spent. After our dinner, during the gloaming, a small pod of orcas appropriated an onshore rock outcrop for a good scratch. What a treat after a long, eventful day!

brown island campsite

The run to Rivers Inlet around Kelp Head is the last bit of Queen Charlotte Sound that must be negotiated. It is nothing like Cape Caution. For one, the 5-mile distance is short, and outlying reefs and islands break much of the swell. The angle too is slightly off. Calvert Island’s protective influence starts to play a role, especially in north and northwesterly blows. Expect to see exceptional populations and varieties of wildlife where this last bit of open Pacific meets the inland corridor of Rivers Inlet. Past Kelp Head and around Cranstown Point (mile 60/497) in Open Bight lies a beautiful, protected beach with excellent beachcombing and camping. There is even a stream and a 40-yard-long primitive trail connecting the protected cove with the Queen’s Pond. The contrast is remarkable. Welcome to Rivers Inlet.

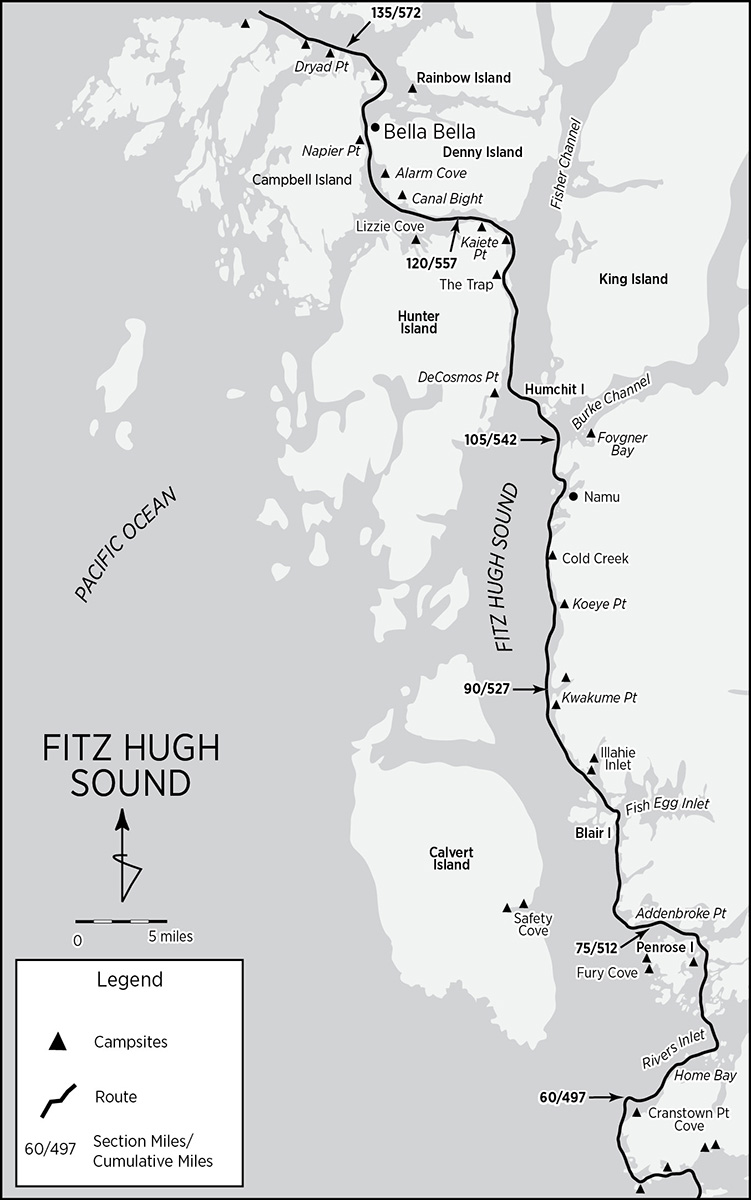

Fitz Hugh Sound: Rivers Inlet (mile 60/497) to Bella Bella/Shearwater (mile 130/567)

Fitz Hugh Sound: Rivers Inlet (mile 60/497) to Bella Bella/Shearwater (mile 130/567)

Compared to the run around Cape Caution, this section, Rivers Inlet and the cruise up Fitz Hugh Sound to Bella Bella/Shearwater, is a paddle in the park. Tidal currents are not a concern. At 2 knots maximum, even these become negligible during runoffs as fresh water pouring into the sound neutralizes floods. Winds are quite predictable: calm in the morning with afternoon breezes that taper off in the evening, unless a low-pressure system threatens or just after one passes and high pressure reasserts itself. Fog can sometimes hamper visibility. Commercial traffic, having given Cape Caution a wide berth outside, funnels inside into Fitz Hugh. Don’t get in the way of large boats and tugs with loads at the entrance to narrow Lama Passage. They must execute a wide but tight turn.

This is the traditional land of the Heiltsuk (Bella Bella) people, with villages once dotting both sides of Fitz Hugh Sound. Namu, the only settlement en route, is one of the oldest native habitation sites along the entire Inside Passage. Archaeological excavations have rendered radiocarbon dates of 8,000 BC. Penrose Island Marine Park, on the north side of Rivers Inlet, encompasses much of Penrose Island and the adjacent archipelago to the south and west. Once out of Rivers Inlet, the foreshore steepens and campsites again become scarce. Much of Fitz Hugh Sound’s west coast is protected by inclusion in the 304,000-acre Hakai Provincial Recreation Area, one of British Columbia’s largest marine parks.

While this guide describes a route up Fitz Hugh Sound along the east coast of Hunter Island, for a description of a more exposed route up the west side of Hunter, see Denis Dwyer’s Alone in the Passage.

Rivers Inlet: Rivers Inlet extends deeply into the Coast Range and, as its name implies, is a catchment basin for an inordinate number of streams, each with heretofore relatively undepleted salmon populations. From spring to fall, each species-specific salmon run attracts predators of all shapes and sizes. Since salmon are the foundation upon which this biotic edifice is built, every living thing congregates to get a piece of the action. The inlet’s protrusion into the mountains is a highway to the coast for grizzlies. Additionally, its contiguity with the open Pacific at Kelp Head attracts species usually found at a greater distance from shore: Dall’s porpoise; minke, northern right, and humpback whales; along with orcas, sea lions, and sea otters.

Man, the ultimate predator, has no permanent presence here, but the seasonal visitors are target fixated on only one thing: salmon. Anglers’ outposts, sometimes quietly fading, reincarnating, or relocating, cater to the annual fish frenzy. Drop by Big Spring Fishing Lodge, Rivers Inlet Sporting Lodge, Black Gold Fishing Lodge, Goose Bay, Bucks Camp, Friendly Finn Bay Retreat, or Rivers Lodge for water or an emergency. Not that these folks are unfriendly, but they are definitely preoccupied. In 1951, sportfisherman Frank Piscatelli (yes, the name is for real) bagged a Chinook weighing 82 pounds. The commercial canneries that once peppered Rivers Inlet—as many as 17 at one time—are all closed now. Most employed native or, prior to WWII, Japanese labor. Only pilings and brick ruins remain. Overfishing has lately become a problem, but environmental groups are now working to restore the inlet’s productivity.

Beyond Cranstown Point the shore rises to steep cliffs, an area known as The Wall, considered one of the top fish producers within Rivers Inlet. Head northeast toward Sharbau Island to position yourself for the inlet’s crossing. Just south of Sharbau, in Home Bay, is the Big Spring Fishing Lodge, built on a recycled railcar ferry barge. (No services are available here, other than water.) Graze by the archipelago guarding the entrance to Duncanby Landing and Goose Bay on the way to Bull Island. Water, showers, laundry, liquor, and limited groceries are available at Duncanby Landing. From Bull Island to Bilton Island on the north shore of Rivers Inlet is a scant 1.5-mile crossing.

Klaquaek Channel: Enter Penrose Island Provincial Park through protected Klaquaek Channel heading due north. The shallow verges of Big Frypan Bay (mile 70/507), just east of Quoin Hill and midway up Penrose Island, plus the many islands dotting Klaquaek, contain a handful of campsites, some on shell middens. Most of Penrose’s goodies (including campsites on Fury Island and Fury Cove) lie in the small island group on the Fitz Hugh side of Penrose, a viable alternative route up into Fitz Hugh Sound. On the Walbran Island side of Klaquaek Channel, Sunshine Bay nestles a small floating itinerant community (no services). At the top end of the channel, a small island (with Rivers Lodge on its north shore) straddles the junction of Klaquaek with Darby Channel.

Turn west into Darby Channel toward Fitz Hugh Sound. Pass Finn Bay at the top end of Penrose Island, home to Friendly Finn Bay Retreat and Bucks Camp, last of the Rivers Inlet fishing resorts. Pierce Bay, the last bay on the north shore before Addenbroke Point, might yield a campsite on one of its many islets or coves. There is an active logging operation at the north end. Once round Addenbroke Point in Fitz Hugh Sound, campsites become much scarcer.

From Addenbroke Point, head north to Arthur Point, coasting along the mainland shore of Fitz Hugh Sound. Across the sound—albeit 5 miles off-route—on Calvert Island lies Safety Cove (mile 77/514), where Vancouver wrapped up the 1792 surveying season. Coastal Waters Recreation Maps indicates a campsite at its head alongside Outsoatie Creek. Tim Lydon, in Passage to Alaska, notes a small, sandy camp along the north shore. Pass by Phillip Inlet into Convoy Passage and head north between Blair Island and the mainland. Cross Patrol Passage to the west and Fish Egg Inlet to the east, over to Salvage Island and into Fairmile Passage. Fish Egg Inlet is extensive and very wild, with isolated lagoons protected by overfalls. It is full of intertidal critters and the wildlife that scrabble a livelihood from them.

North of Salvage Island, Illahie Inlet, fronted by the Green Island Group (mile 85/522), cuts into the mainland. The Green Island Group has a couple of campsites. One, shown on the Coastal Waters Recreation Maps, we did not persevere enough to find. It is located on Green Island itself, north of the giant midden site on the west side. The other covers a small, bare rock islet just off the northwest corner of the largest island at the entrance to Illahie Inlet. If you can hold out, there is a much nicer campsite 4 miles farther north.

About 0.5 mile south of Kwakume Point (mile 89/526), two treed islets are connected to shore by a white sand beach. Overnight accommodations just don’t get better than this. Kwakume Point itself has a light. Another 0.5 mile or so north, Kwakume Inlet (mile 90/527) cleaves the mainland. Just 0.75 mile inside the inlet, along the north shore, there is another campsite. Remember that the entire mainland coast south of Namu is grizzly country; camp defensively.

Koeye River: The Koeye River (mile 95/532; pronounced “Kwy”) has significance disproportionate to the modest watershed it drains. In 2001 the Raincoast Conservation Society, Ecotrust Canada, and The Land Conservancy of British Columbia deeded a 183-acre parcel and lodge at the mouth of the river to the Heiltsuk and Owikeeno First Nations, original stewards of the Koeye. On August 11 of that year, more than 300 members of those tribes, invited guests, and chance visitors gathered at the Koeye to celebrate the transfer of ownership. Additionally, much of the moss-draped, old-growth forest lining the river is now protected from further logging. Just inside the mouth, along the south shore, are some good campsites. About a mile up the channel, the ruins of the Koeye Lime Company line the north shore, upstream of which the river widens into a grassy plain with stunning views of snow-capped peaks to the east. Wildlife abounds.

Three miles north of the Koeye and just below Uganda Point, the Cold Creek (mile 98/535) delta has a good camp on a long pebble beach, perhaps—in terms of bears—a safer alternative to the Koeye. Head north past Ontario Point into the small channel between Lapwing Island and the mainland and into Namu Harbour.

orcas in fitz hugh sound

Namu: Namu (mile 102/539) does not present a lovely first impression. Paddling up in a kayak, the industrial conglomerate, extended over the water on giant piers, overwhelms the natural beauty of Whirlwind Bay. Out of the corner of your eye, however, you can spot its outlying extremities: old white clapboard buildings connected by an intricate system of wooden walkways and piers ingeniously wending their way through the contours of the landscape, subtle hints of the delights hiding behind the dreary façade. Namu (meaning “whirlwind”) is a 10,000-year-old Heiltsuk settlement that has been continuously occupied to the present. Six thousand years ago, with growth sluggish and GDP flat, Namu’s citizens launched a radically new economic development scheme: salmon exploitation. Ever since, salmon have been the economic mainstay of the area. In 1893 Robert Draney, a European Canadian, opened the first fish cannery in the village. The enterprise thrived and grew, adding a sawmill in 1909. British Columbia Packers Ltd. bought out and consolidated all the Namu operations in 1928. For more than 50 years, under the benevolent company town regimen of BC Packers, Namu supported a population of Heiltsuk, other First Nations, European Canadians, Japanese, and Chinese—all told, up to 400 personnel and their families.

The cannery shut down in 1980. Processed fish were then shipped south to Vancouver and west to Japan. In the early 1990s, the processing plant discontinued operation and BC Packers sold out. Attempts to resuscitate Namu as a fishing resort have required frequent intervention and intensive care. Namu, though barely holding on to life, has good prospects. The Heiltsuk are currently seeking to regain this property and have it designated a Canadian and World Heritage Site.

A multitalented family of caretakers keeps the central core of the old town spruced up and is slowly increasing the variety of services available. They sell gas, run a limited-services machine shop (a godsend when one of our rudders broke), maintain a few dwellings for “bed & shower” rentals, mow the lawn, and even offer tours (run by an industrious daughter for a nominal “donation”). There are plans to reopen the café and store. At the time of our visit, the old store still had quite a selection of leftover dry goods from which the caretakers kindly let us reprovision, gratis.

You can camp on Clam Island just offshore. A better bet is to ask permission to pitch a tent on the spacious mowed lawn behind the mooring docks (there may be a charge). Use of the bathrooms, a not-negligible environmental concern, is included. Spend a day touring the town and hiking up the boardwalk to Namu Lake, source of the island’s generator’s power. The elevated walkways are surrounded by berry bushes and are so high up that bears can harvest the berries below undisturbed by human traffic. Many of the buildings are well preserved and evoke a nostalgia for an era long past. At night, with the generator lighting up the entire place, the walkabout is particularly eerie and rewarding. Don’t miss the historic native community and Asian compound on the south side of the Namu River. A stone fish trap at its mouth is one of the few visible reminders of the prehistoric occupation of Namu.

One summer morning in 1965, salmon fisherman Bill Lechkobit found two killer whales, a bull and a calf, caught in his net near the Namu cannery. Sensing an opportunity, instead of setting them free, he offered them to Ted Griffin, owner of a Seattle aquarium. Griffin promised Lechkobit a handsome profit for the whales’ safe delivery. By the time the fisherman had built a floating pen for the long tow down the windy waterways to Seattle, the calf had escaped. Still, Lechkobit was lucky. On the way down, the pen held, Cape Caution and the weather cooperated, and the remaining whale survived the indignities of the passage. In Seattle, the orca was installed in a pen named for where he was captured: Namu. He became a celebrity, which fostered a new appreciation for orcas and whales generally.

North of Namu, the route up the Inside Passage zigzags west and north, following channels laid out along geographic weaknesses. At some point, Fitz Hugh Sound must be crossed. But where? South of its intersection with Burke Channel, Fitz Hugh is broad and subject to the squamish (katabatic) winds that blow down Burke, a steep, glacier-cut inlet snaking deep into the Coast Range. North of Burke, Fitz Hugh narrows considerably and becomes Fisher Channel.

Depart Namu early. Burke’s winds don’t usually kick up until after 10 AM. Time the crossing—if possible—of Burke’s mouth with a waning flood and stay out where the entrance is widest. Strong tidal currents bedevil Burke. Before Edmund Point (mile 105/542), angle out toward Humchitt Island. Just inside Burke Channel, on the south cove of the largest island in Fougner Bay and about 1 mile east of Edmund Point, there is a campsite. From Humchitt Island, cross Fisher Channel, still on a waning flood or slack and early in the morning, to De Cosmos Point on Hunter Island.

Just 0.5 mile below the point, the entrance to De Cosmos Lagoon (mile 110/547) beckons. The lagoon is nearly landlocked and its entrance is choked with kelp and overhanging tree branches. Strong currents enter and exit. But just inside, on the north shore where a creek disgorges, is a small campsite.

Head up Fisher Channel along Hunter’s east shore into the passage between Clayton Island and Hunter. A broad alluvial plain, nicknamed “The Trap” (mile 115/552), opens up on Hunter’s shore. Camping is possible, though not particularly aesthetic. Continue north past Long Point and Long Point Cove to Pointer Island and Kaiete Point.

Kaiete Point (mile 117/554), the entrance to Lama Passage, once had a manned lighthouse. Today only a helipad remains. If you can negotiate a landing, there is no better campsite. With powerful views up and down Fisher Channel and into Lama Passage, a night on the helipad is like camping out inside a symphony.

Sir Alexander Mackenzie Provincial Park: Thirty miles farther up Fisher Channel from Lama Passage (after Fisher becomes Dean Channel) Sir Alexander Mackenzie Provincial Park commemorates the first recorded transcontinental trek across then-unmapped North America. Mackenzie’s feat in 1793 was one of the most phenomenal exploratory ventures ever accomplished. Though a bit distant from the Inside Passage route for a side trip (unless you’re as ambitious as Mackenzie) and outside the scope of this guide, the park is accessible by float plane or powerboat from Bella Bella.

When Alex Mackenzie (the knighthood came later) set out to find the Pacific in 1789, the United States had not yet fully ratified its new Constitution, and Lewis and Clark were mere teens. Mackenzie did not ask for and did not get any government support. Though keenly aware of imperial concerns and the expansion of geographic knowledge (Lewis and Clark were later to rely on and carry Mackenzie’s Voyages from Montreal), Mackenzie’s primary aims were commercial: market advantage for his North West Company. He was an intelligent, determined, patient, linguistically gifted, and extremely diplomatic Scotsman. Traveling mostly with native companions employed along the way, it is a testament to his talents that Mackenzie survived and prevailed over extraordinary circumstances.

Mackenzie reasoned that beyond the Continental Divide streams would flow into the Pacific. His strategy was inferentially simple but realistically complex. On his first try he descended the unexplored Mackenzie River, second only in size to the Mississippi-Missouri watershed in North America, and followed it to the sea, which turned out to be the Arctic instead of the Pacific Ocean. Lesser men would have been satisfied. Unflummoxed and undeterred, Mackenzie retraced his steps and turned west. But his companions had had enough: not one accompanied him.

Thoroughly committed and inured to hardship, he recrossed the plains, surmounted the Rocky Mountains, and ran headfirst into the Coast Range and the animosities separating the interior from the coastal tribes. Finally, under extreme danger to his life from distrustful and bellicose Bella Coola and Bella Bella natives, he reached the Pacific at Dean Channel and there inscribed on a rock: ALEX MACKENZIE FROM CANADA BY LAND 22 JULY 1793. The inscription, now incised into Mackenzie’s Rock, is the centerpiece of the park. Camping, though not much else, is available.

Outbound, Mackenzie had averaged a phenomenal 20 miles a day; on the return, he picked up the pace to 25. Ironically, through a chance meeting with a Bella Bella (now Heiltsuk) native, he found out that he had missed Captain Vancouver, busy mapping Dean Channel on his first expedition, by only a few weeks.

Lama Passage, southernmost of three channels leading west to Bella Bella, is the most popular and shortest route up the Inside Passage. Be aware of traffic. Two miles in, on the east side of Serpent Point Light (mile 119/556), there is another campable spot. The remaining north shore of Hunter Island along Lama Passage is indented by at least five coves with outlying islands. Many have camping possibilities. We camped on one of the islands in Lizzie Cove, also known as Cooper Inlet (mile 123/560), site of an old native village.

A better bet is to course along the Denny Island shore. There is a camp on Canal Bight’s (mile 125/562) outermost cove. Another mile up the coast, behind Walker Island (mile 126/563), which has a light, lies another campsite. Alarm Cove’s (mile 126.5/563.5) southern incut also has camping.

After Napier Point, in Lama Passage’s narrowest section, you enter the Bella Bella conurbation: Waglisla, Bella Bella, and Shearwater. Inside McLoughlin Bay (mile 129/566) the BC Ferries terminal services the area. Immediately afterward, SeeQuest Adventures’ headquarters—a kayak tour outfit—lines the shore. They can provide, among other services, a campsite and taxi service into New Bella Bella. There is no camping inside Bella Bella proper, except at slightly out-of-the-way Rainbow Island (see below), and the nearest campsite afterward is 3 miles beyond the towns, so plan your stopover with these camping details in mind.

lizzie cove camp

Bella Bella/Shearwater: Bella Bella, New Bella Bella (Waglisla), and Shearwater (mile 130/567) are the three more or less contiguous settlements that sprang up around the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort McLoughlin since 1833. Bella Bella and Waglisla were (and primarily remain) native settlements established to facilitate trade with the fort. Shearwater is the most recent addition. What started out as a Royal Canadian Air Force WWII base has expanded into a resort. The three combined are the largest outpost of civilization between Port Hardy and Prince Rupert, with a combined population of about 2,000. All services are available. Groceries, liquor, charts, post office, water, restaurant, and RCMP are best accessed from the Waglisla government dock near the north end of New Bella Bella or in Shearwater. The campsite in Shearwater is up the hill, away from the water. Don’t miss the Heiltsuk Cultural Education Centre, located in the Bella Bella Community School just up from the wharf, for information on Heiltsuk history, language, and culture. Camping is available at the already mentioned SeeQuest Adventure headquarters and on the north end of Rainbow Island, just northwest of the three towns. There are also B&Bs and hotels.

The Heiltsuk have a reputation for hostility. Alexander Mackenzie, a model of tact and understatement, after being belligerently accosted by the informant that relayed a not-too-friendly encounter with the Vancouver expedition, states: “I do not doubt he well deserved the treatment which he described.” More recent visitors, including a few kayakers, sometimes describe ominous exchanges. Perhaps first impressions can be deceiving. The Bella Bella whom Mackenzie encountered had a strong martial tradition. They assumed all visitors were warriors bent on personal glory, so a challenge was the best greeting to extend.

Heiltsuk chauvinism was built on a foundation of tenacious self-reliance and independence. To themselves, they were second to none. Ever prickly but ingenious, the Heiltsuk coped with contact resiliently. Fort McLoughlin was supplied by the Beaver, a side paddle-wheeler and the first steam-powered vessel on the Northwest Coast. For more than 50 years the Beaver plied the Inside Passage, a floating mercantile and often the only source of external contact for the inhabitants. After the decline of the sea otter, other furs such as beaver, river otter, mink, and marten were traded for woolen and cotton clothing, axes, gunpowder and shot, blunderbusses, muskets, sugar, molasses, tobacco, rice, vermilion, iron, indigo blue blankets, scissors, butcher knives, looking glasses, needles, and pea jackets. With smoke bellowing from her stacks, a large woodcutting crew to feed her engines, and four brass cannons, she was an impressive sight made more so, to the natives, by the mystery that she had no visible means of propulsion. John Dunn, trader and interpreter stationed at Fort McLoughlin in the mid-1830s, relates the following incident:

They (the natives) promised to construct a steamship on the model of the Beaver. We listened and shook our heads incredulously: but in a short time we found they had felled a large tree and were making the hull out of its scooped trunk. Some time after, this rude steamer appeared. She was . . . thirty feet long, all in one piece . . . resembling the model of our steamer. She was black, with painted ports; decked over . . . the steersman was not seen. She was floated triumphantly. . . . They thought they had nearly come up to the point of external structure; but the enginery baffled them; this, however, they thought they could imitate in time by perseverance and the helping illumination of the Great Spirit. (Dunn, History of the Oregon Territory, 1844)

In recent years the Heiltsuk have bent over backward to improve their image and attract more tourism. With the 1996 opening of the Discovery Coast ferry, this entire area has become more accessible. Our own experience was very friendly—we were offhandedly offered an outlying cabin—but otherwise uneventful.

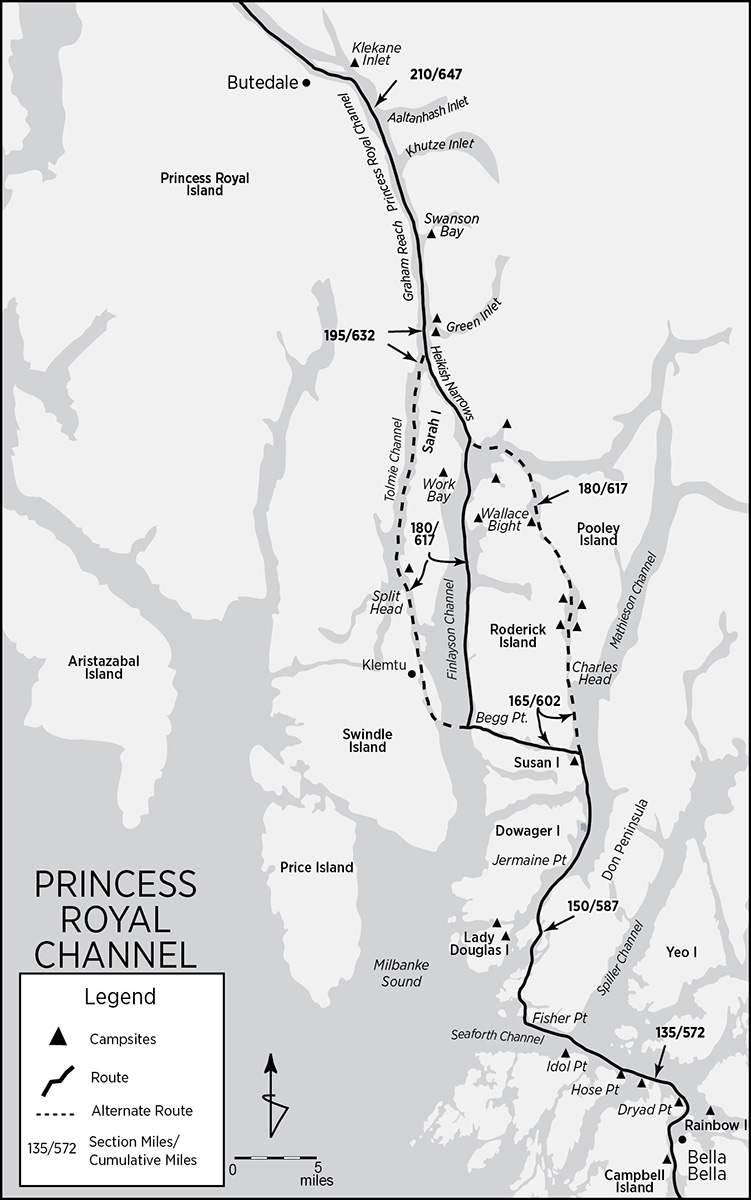

Princess Royal Channel: Bella Bella (mile 130/567) to Butedale (mile 214/651)

Princess Royal Channel: Bella Bella (mile 130/567) to Butedale (mile 214/651)

The third portion of the central coast begins with a couple of long zigzags that access three alternate approaches, more or less of equal length, into Princess Royal Channel, which separates Princess Royal Island from the mainland. It is wild and steep, subject to strong currents, and very isolated. Klemtu and Butedale are the only outposts of civilization, with Butedale barely so. Campsites are scarce, and not just due to harsh terrain. Klemtu is Kitasoo First Nation’s territory. In the past, the Kitasoo, lacking a tourism policy, had asked that their area not be promoted in paddling guides—though they welcomed visitors. Now, visitors are asked to register with the Klemtu tourism office (see Appendix B) before conducting any activities in the area. All my research notes on this area were lost in a car accident, so I rely on my ever-fading memory for campsite locations. Lack of marked campsites on the accompanying maps does not indicate their absence, only their paucity and the author’s inadequacy.

Seaforth, Mathieson, Finlayson, Tolmie, and Princess Royal channels are the primary traffic routes up and down the Inside Passage along this section. Winds freshen in the afternoons and—in the long, narrow sections—can be funneled with alarming velocity. The main route, after Seaforth Channel, goes up Mathieson Channel, across Jackson Passage to Finlayson Channel, and straight up into Heikish Narrows, where it joins Princess Royal’s Graham Reach.

The two alternates offer, on the one hand, more of the same or, on the other, a stark choice. Alternate #1 curves over to Klemtu, where it rejoins the ferry route up Sarah Pass and Tolmie Channel into Graham Reach, a tad longer than the main route. Alternate #2 skips Jackson Passage and goes straight up through uncharted Griffin Passage, a narrow and rapid-strewn wilderness adventure, actually a tad bit shorter than the main route. The two alternate routes are described immediately following their point of convergence with the main route.

For something completely different, Denis Dwyer, in his Alone in the Passage, completely avoids Princess Royal Channel and paddles his way up the more exposed Laredo Sound, between Aristazabal and Princess Royal islands. Check out his guide if you’re tempted to go this route.

Nearly abandoned Butedale separates Princess Royal Channel’s length into Graham and Fraser Reaches. The old cannery is a welcome haven and offers a convenient respite and terminus for this portion.