2

DETAILS

Survival is not so much a question of enduring adversity

as of avoiding it.

—R. H. M.

Where to Go

Exactly where to begin or end an Inside Passage journey, what route to chart, and even in which direction to travel can be points of contention. The northern terminus presents few options: Lynn Canal or Glacier Bay. Going to Skagway, at the head of Lynn Canal, has the attraction both of being the historical objective and the most northerly end point. Not only is the town well connected both by road and the Alaska Marine Highway, but also the White Pass & Yukon Route Railway has recently reopened. For the really adventurous, Chilkoot Pass and the Yukon River still beckon.

With Glacier Bay, however, one still has to choose between Muir Inlet and the West Arm, the longer of the two. Both have tidewater glaciers and lots of wildlife. The phenomenally rapid retreat of Muir Glacier, which was the most frequently visited glacier in North America until the National Park Service (NPS) stopped motorized travel at the head of the inlet, has left a spectacularly vertiginous canvas of scoured and naked rock with few places to camp. It now barely qualifies as a tidewater glacier (one whose ice is actually advancing into the sea). Johns Hopkins Glacier in the West Arm, on the other hand, is the largest, most impressive tidewater glacier in Glacier Bay National Park, constantly calving icebergs at an almost predictable rate. The heads of navigation in Glacier Bay, should one choose to end one’s Inside Passage trip here, are wilderness destinations and require either paddling back to park headquarters at Bartlett Cove afterward or arranging for a commercial shuttle (offered on a daily basis).

It can be difficult to decide just where to end this magnificent quest. For us, we were torn, so we took the unconventional decision of paddling all three major northern fjords. This book takes the same approach: all three possibilities are covered.

Off the exposed headlands of Cape Caution, in Queen Charlotte Sound, we met a pair of Japanese riding the swell in a tubby double kayak. They had lots of cameras and engaging smiles but not a whit of English. Forty days out of Skagway, they were white-knuckled for Vancouver. They chose Vancouver not just to lessen their overall mileage, but also to avoid, for them, yet another international crossing with its enervating formalities. Additionally, they had a nonstop Vancouver-Tokyo flight back. The options for a southern terminus are many. Vancouver and Seattle are the historical nexuses. Unfortunately, really big cities present their own logistical problems for the low-profile kayak traveler, and Vancouver eliminates Puget Sound, not only a stellar paddle but also a profitable shakedown cruise, if chosen as the start. Most Inside Passagers start or end in Seattle. We, on the other hand, didn’t want to miss a single possible mile and so embarked from Olympia, the southernmost point on Puget Sound.

Choosing a route between Olympia and your chosen northern terminus, after a cursory glance at a map (for which map is best suited to this exercise, see The Bottom Line I: Navigation), can leave one bug-eyed and befuddled. A simplifying algorithm is necessary. First, pencil in the absolute shortest distance between your start and finish, irrespective of whether it coincides with a ferry route or conventional navigation channel (after all, we are kayakers). Why the shortest? For one thing, one has to start somewhere and, in a paddling trip of more than a thousand miles, shorter has its logic. This route also has the advantage of being randomly picked, so a true sampling of the Inside Passage is guaranteed.

Next, pencil in any alternative routes that might be preferable from a safety aspect—for example, fewer crossings, less current, protected shore, and so forth. Then circle specific destinations along the way that you want to visit (such as Mackenzie’s Rock, the Brothers Islands, Baird Glacier, Pack Creek, Ketchikan, etc.) or avoid (e.g., Seymour Narrows, Vancouver, rapids, etc.). Next, conform what you have into a route.

Finally, wish real hard while looking at the map and note where ideal time-saving portages ought to be and, voila, they may appear. This is not as crazy as it sounds. At the head of Seymour Canal, connecting it to Oliver Inlet, is the most endearing little portage tramway on Admiralty Island, about a mile long, that’s a real hoot to use. A portage also connects Port Frederick with Tenakee Inlet on Chichagof Island. Some portaging (or lining) will be inevitable due to tides or rapids. These may include sections of Gastineau Channel, Griffin Channel, Dry Strait, the Skeena River delta, the Couverdeen Islands, and campsites with a dry foreshore at low tides. But take heart, we welcomed most portages as a delightful respite from the paddling. You’ll now have a route with some out-and-back detours such as, for example, Mackenzie’s Rock or Baird Glacier. Decide whether these detours will really enrich your trip and either excise them or plan on visiting them via some alternative means, such as floatplane or hired boat mini-tour. Now you’ve got a route you can work with, and although it may not coincide entirely with the primary one in this book, it’ll probably share many large portions.

For some people, deciding whether to go north-to-south or south-to-north is a serious concern. Not for me. I could no more start in Glacier Bay, headed for Puget Sound, than I could run a river against the current, climb a mountain from the summit down, or watch a movie in reverse. Sea voyages always start at homeports bound for the nether regions. A south-to-north trip recapitulates both the early explorers’ efforts and the Klondikers’ quest. Additionally, as one progresses north, the transition from temperate climes to a more antipodal environment is experienced firsthand. The lush and diverse forests of the Puget Sound-Vancouver Island region give way to the giant red cedars of British Columbia, so beloved by turn-of-the-twentieth-century loggers and now nearly gone; then to western hemlock and Sitka spruce (now heavily logged) in the Alaska Panhandle; and, finally, to the receding glacier, alder-recolonized bare rock of Glacier Bay, the icy jewel of this paddling crown. The return trip home makes for a good “decompression” interval and a fitting resolution to a magnificent adventure, especially if it takes place on a ferry.

The justification for a north-to-south voyage might be if your homeport is Skagway or Juneau or, more commonly, to follow prevailing winds. Fortunately, during the paddling season—May to mid-September—Inside Passage weather is generally benign, with prevailing winds evenly split from both directions, though there is much controversy on this matter. An informal (and, admittedly, very restricted) survey of north-to-south paddlers indicates that their primary motivation was to “paddle home,” usually the Vancouver or Puget Sound area. And a satisfying finale that would make. Unfortunately, most returned with the impression that the prevailing winds blew against them. Admittedly, one might expect such a conclusion. However, south-to-north paddlers (again, in a very limited and informal survey) concluded that they mostly ran with the wind.

Weather and When to Go

The Gulf of Alaska is the point of conception and maternity ward for virtually all North American low-pressure systems. The Japanese Current brings warm water from the tropics and, as it passes the Bering Strait, draws in cold water from the Arctic Ocean, which then mixes in promiscuous eddies. These in turn affect atmospheric air directly above them by altering its temperature and humidity. Extreme temperature, humidity, and pressure gradients close to each other generate winds and instability. These infant storms crash into the Coast Range (global weather, due to the earth’s rotation, always moves eastward—the Coriolis effect) and often nestle for weeks in the crescent-shaped cradle of the Alaskan-Canadian coastal embrace, their movement further impeded by the Coast Range. When they’re finally ready to move on, lows don’t always go due east. Exactly where they go is a function of nearby high- and low-pressure systems that, like features in a pinball machine, can attract and repel. But they always follow the path of least resistance. This constantly fluctuating, sidewinder-like path is the jet stream. Meteorologists have labeled its major crests and troughs “Pacific High” and “Aleutian Low.” Every equinox they take turns setting the stage for climatic events in the region.

Certain practical implications follow from this model. One is that precipitation decreases from north to south and west to east, since lows are always moving eastward. The mountainous barrier eases a bit between Cape Scott, at the northern end of Vancouver Island, and at the Seattle area, allowing storms to slip through. As a storm ascends a mountain barrier, its rapidly rising air cools and loses its ability to hold water. Phenomenal precipitation results. Areas in the lee of a mountainous land barrier—which has already sucked some of the water out of a storm—can be dramatically drier, such as the Gulf Islands.

Winter storms are more intense and more numerous because the temperature differential between the Japanese Current and winter arctic air and sea is much greater. Not that one would ever kayak the Inside Passage in winter. But how early to start and how late to stay might be of greater concern.

Because winds blow from high-pressure systems to low-pressure systems, when there’s a low in the Gulf of Alaska, it’ll blow from the southeast; when there’s a high, winds will come out of the northwest. I hesitate to say this but (refer to the legal disclaimer at the front of the book), ceteris paribus, winds are not a major concern for the paddler along the Inside Passage. Having spent close to 24 weeks kayaking in the Sea of Cortez (and about 16 along the Northwest Coast), I’ve spent many more wind-borne “down days” in Mexico (sometimes as often as every other day) than I have along the Inside Passage (none). Not to say it can’t happen (again, refer to that bit at the beginning)! When a narrow channel constricts a breeze, it can intensify, and if it opposes a strong current—watch out! The chop can not only be unnerving, it can turn downright dangerous if coupled with cliffy shores and their resultant clapotis (the maelstrom produced by waves breaking and reverberating off walls). Katabatic winds, caused by warm air rapidly rising as it hits a mountain barrier and then, when cooled, shooting down its flank, are very local but very strong. (We never experienced worrisome katabatics along the Inside Passage but have, often, in Baja California.) Temperature differentials take time to build up, so calmer conditions prevail during the early morning. This is the optimum time to paddle. Exposed shores, subject to Pacific swells generated by winds a quarter of a world away, can also wreak havoc in the form of surf.

Superimposed on the natural trend for temperatures to vary according to latitude and altitude is variation according to distance from the tempering influence of the warm Japanese Current. Inside Passage temperatures, in spite of the constant pummeling of winter storms, remain mild. Juneau’s average winter temperature, at 29°F, is warmer than Chicago’s (or, for that matter, Moscow’s—and both are considerably farther south). Summer averages are in the 60s, with many days reaching into the high 70s and low 80s. At Glacier Bay it is considerably cooler. Mid-40s to mid-60s are the daytime summer averages, with temperatures dropping further at night or near glaciers. South of Princess Royal Island it can get downright hot. Although July daytime averages in Seattle, Victoria, and Vancouver hover around 72°, windless heat waves can raise the temperature into the high 90s. In fact, the mainland side of the Straits of Georgia is known as British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast.

“I’m never sleeping with you again!” declared Tina, more frustrated than angry. We were camped on a cobble beach along Broughton Strait opposite picturesque Pulteney Point lighthouse. It had been a long day. Fog—formed when warm air moves over relatively colder water (more commonly in late summer and fall)—materialized like a spectral apparition, making time stand still. What a soothing delight. But just as our heads nestled down in our stuff-sack pillows, the loudest tuba in the firmaments cold-cocked us. Our earplugs were about as useful as adopting a positive attitude. It never crossed our minds that lighthouses become foghorns (duh!) when visibility is impaired. Don’t let fog add discord to your marriage. Otherwise, it’s only a nuisance when contemplating crossings. Better to wait until it lifts.

Just what exactly is fog? How can you get a sense of when it’s likely to form or, more importantly, dissipate? There are two sorts of fog: radiation and sea fog. Both are easily understood, more or less predictable, and reasonably managed. Along the Inside Passage, during the summer paddling season, radiation fog is the primary occurrence. Precipitation can be categorized along a continuum from its mildest forms, fog and dew, through drizzle, all the way to a driving deluge. Lee Moyer, in his excellent Sea Kayak Navigation Simplified, has explained it quite succinctly:

All fog is formed in the same way: air cools to the point where it can no longer hold all its water vapor and the vapor condenses out as small droplets that are so small they are held in suspension and do not fall. If they get big enough to fall, they are called rain. Warm air can hold more moisture than cold air, which is why we use warm air to dry things. If it cools, the water comes back. The fraction of the total capability of the air that is actually used to absorb the vapor is called the relative humidity. Fifty per cent relative humidity means the air holds half of what it could hold. You get that sticky, clammy feeling when the air is holding about all the water vapor it can hold, and nothing will dry. As the temperature drops and the ability of the air to hold moisture decreases, eventually the temperature reaches a point where the air can hold no more moisture. That temperature is called the dew point. Dew will form on items that are cooler than the air. Typically, as surfaces radiate their heat away in the evening, they reach a point where they cool the air they touch and dew forms. When the air itself reaches that point, fog forms. Thus, fog will form in the cool of the night, be there in the morning and maybe burn off as the day warms up.

Radiation fog, as this type is called, forms as heat radiates away and air cools. It cannot coalesce when the wind blows, as the turbulence would mix the temperature variations and prevent fog from forming. Likewise, warming air in the morning or a building breeze will cause it to dissipate.

Sea fog, on the other hand, though materializing in the same way, is a different phenomenon. It forms offshore, is brought in often by strong winds, and comes in a big wall called a fog bank. Neither does the wind die quickly, nor does the fog burn off any time soon.

During the summer months, Inside Passage weather follows a pattern that is quite predictable: a series of clear days with a moderate headwind, followed by a few days of rain accompanied by a moderate tailwind. Diurnal micro-weather is also reassuringly dependable. Nights are calm and quiet, with fog or low clouds moving onshore. Mornings are God’s gift to sailors. In the afternoon, moderate breezes pick up, dissipating the fog and clouds and creating a 1- to 3-foot chop, until evening when conditions calm again.

But weather is not the only concern when timing an Inside Passage venture. Nature’s tides are also worth catching. Salmon runs occur in mid to late summer. They are not to be missed, and neither are the bears taking advantage of them, particularly at Pack Creek and Anan Creek. Human salmon-fishing season is a bit earlier. You can participate in the harvest either by catching your own or grubbing off the commercial and subsistence fishermen. The summer solstice is June 21. Berries ripen in August. Various cultural events, from the Tulip Festival in La Conner (spring), to Canada Day (July 1) throughout the provinces, to Chief Seattle Days in Suquamish (August), pepper the paddling season.

If attempting the entire passage in one go, it’s probably best to begin in early May. This avoids the really high temperatures possible in midsummer on the southern half and the “paddler’s conundrum”—that is, dressing for water temperature instead of for air temperature. Warm weather in this context, ironically, can be a hazard. Who wants to dress for 50°F water when the air temperature is 90°?

If you’re doing the trip piecemeal, Puget Sound can be done anytime, though the above considerations still apply. All the other sections have no particular “best” time within the paddling season (although below Desolation Sound the paddler’s conundrum is still a concern) except for Glacier Bay. Late May and early June seem to offer the clearest weather at the northern terminus.

Getting To and From There

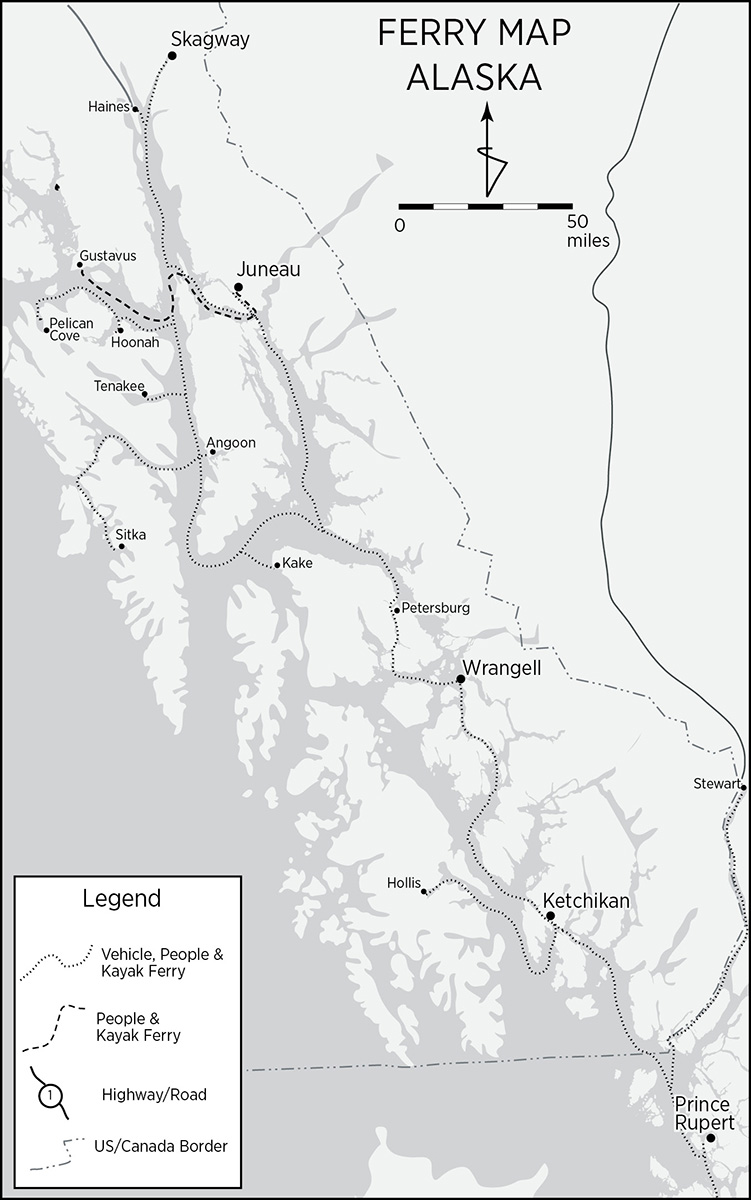

Part of the appeal of the Inside Passage is its relative inaccessibility by car. Ironically, the Passage is also the easiest medium for accessing this complex coast. The geomorphology of the area precludes bridges and makes road building extremely difficult and costly. Loggers have even resorted to helicopters to retrieve their harvest. This handicap has been the source of an ongoing controversy over the location of Alaska’s capital, Juneau. Should it be moved to Anchorage or Fairbanks, or perhaps some new spot in between? Engineering proposals already exist to extend the highway south from Skagway to connect with Juneau. Local resistance has put this option on hold for now. Juneau residents fear an influx of “undesirable elements” and a loss of their small-town atmosphere.

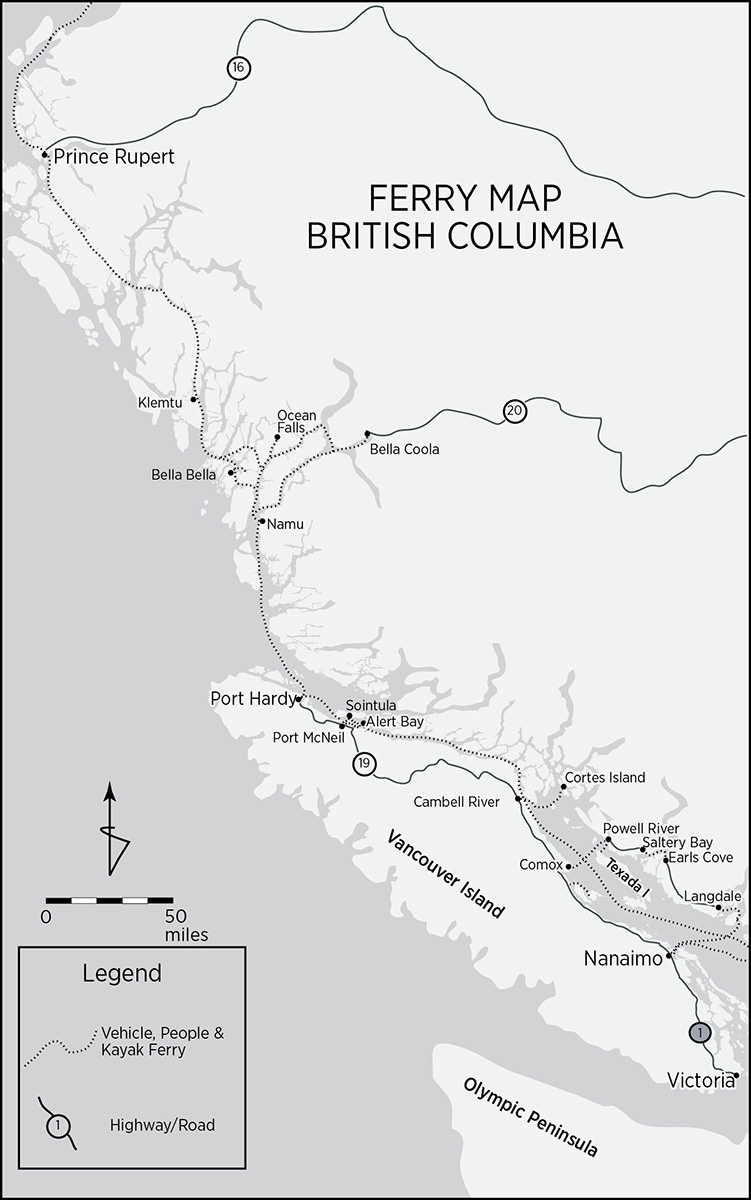

Coming up from the south, direct vehicular access to the coast extends as far north as Vancouver. On the central coast, Bella Coola, Kitimat, Prince Rupert, and Stewart have arterial connectors from the Al-Can Highway. One can also drive to Skagway and Haines at the northern end.

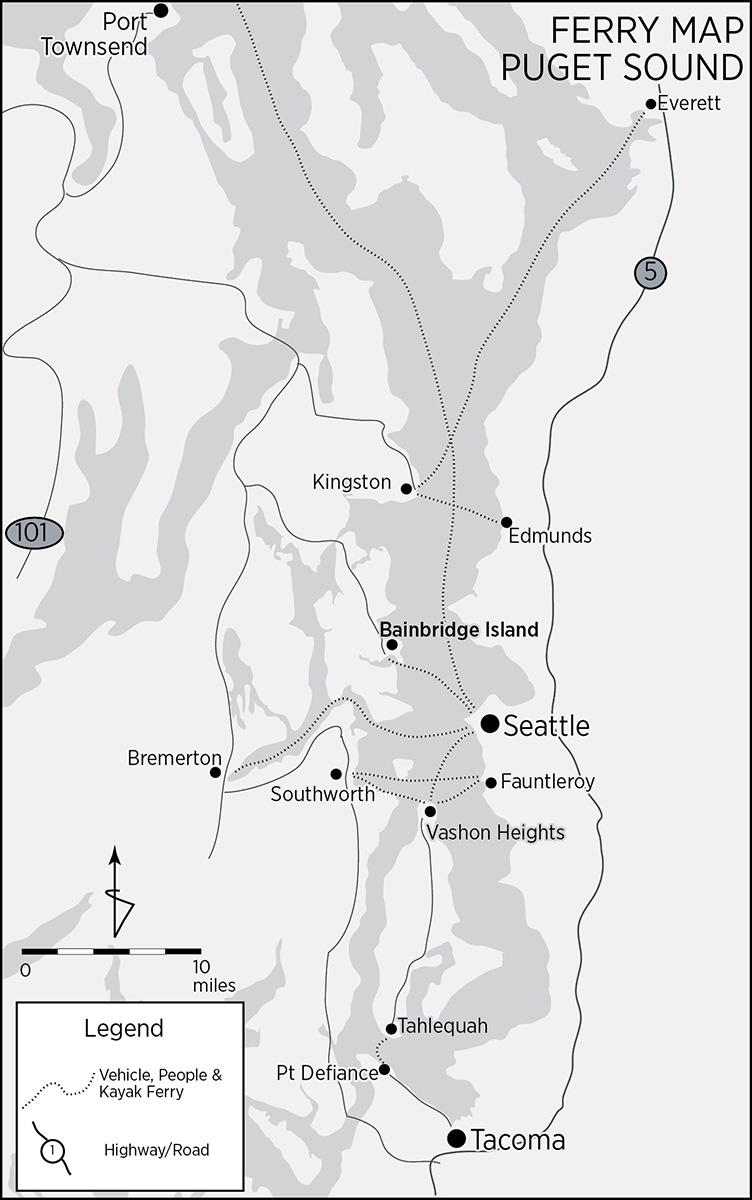

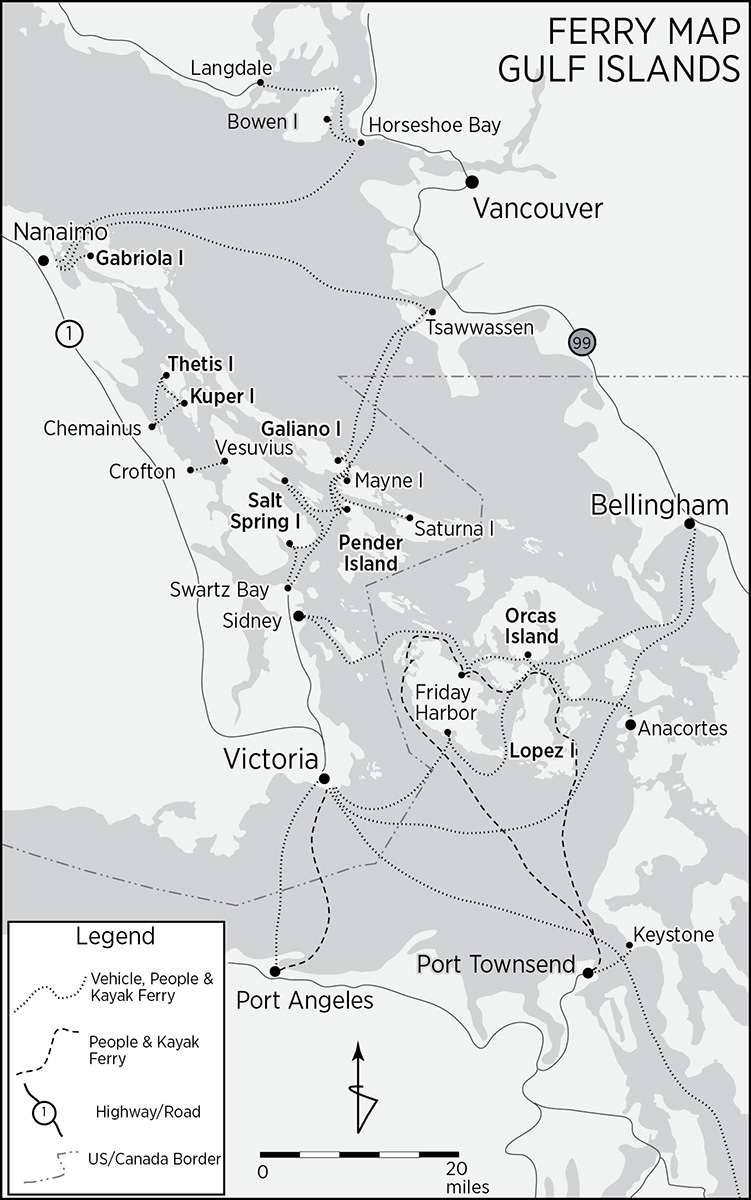

The solution to the motorized access problem has been the development, in all jurisdictions, of some very sophisticated ferry systems for both cars and, in some instances, pedestrians only. Two short ferry rides connect the southern highway terminus with another 80 miles of road up to Lund, BC (on the mainland), while another single one opens the door to the entire length of Vancouver Island. Intricate ferry networks connect virtually all settlements along the Inside Passage and Puget Sound.

The three main ferry systems—Washington State Ferries, BC Ferries, and the Alaska Marine Highway—are government owned and operated. Washington State Ferries are first-come, first-served, short-run affairs, connecting nearby communities that would otherwise require a long drive or are located on unbridged islands. The ferries are the missing bridges and operate only in the state of Washington, with one important exception. Washington State Ferries also operates internationally between Anacortes, Washington, and Sidney, BC.

The Alaska Marine Highway, as its name implies, is southern Alaska’s highway system and, consequently, sticks mostly to long haul. Along the Inside Passage, the Alaska Department of Transportation operates eight ferries serving 14 communities. It also links with both the British Columbia (at Prince Rupert) and Washington State (at Bellingham) ferry systems. In 2002, the Bellingham-to-Skagway haul ran once a week at a cost of $900 for one adult with a vehicle, one-way. These big, long-haul ferries can accommodate up to 625 passengers and 134 vehicles. All have restaurants, bars, lounges, gift shops, and even staterooms. At about 16 knots, the trip takes about 62 hours. Some 310,000 passengers make at least part of the ferry journey every year.

BC Ferries are both short haul and long haul and operate only in British Columbia. The province runs 40 ferries, some as far afield as the Queen Charlotte Islands, though most operate around small communities near southern Vancouver Island.

A small but important selection of private ferries fills specialty niches that the state and provincial ferries overlook. Most of these connect Victoria, BC, with various cities in Washington; another one services the San Juan Islands. Consult the route map for a full layout of all ferry routes.

All car ferries will carry kayaks and most people-shuttle ferries will also. All charge a nominal fee. When possible, ferry your boat and trip gear without a vehicle. It may not be as complex as you imagine, even when solo. With kayak wheels you can lade a fully loaded kayak onto or off the ferry without help. Long-haul ferries accommodate campers on the covered (and heated, when necessary) solarium deck and provide hot showers. Long-term parking is usually available—double-check this—at ferry terminals.

For short-haul ferries, taking the car along is not much of a problem. However, with long hauls (including the Washington State Ferry between Anacortes, Washington, and Sidney, BC, and all private ferries between Puget Sound and Vancouver Island), during peak season car reservations are a very good idea, and the expense is much greater. In all situations, notify the ferry that you are carrying a kayak. By the way, only one kayak per passenger is customarily allowed for walk-ons. Arrive early so the crew can make necessary preparations.

People-shuttle ferries require a different approach. Empty the kayak and consolidate your dunnage. Wheels are unnecessary—the kayaks are usually loaded over the rails, with the gear remaining with the passenger as luggage. Here as well, notify the crew that you’re carrying a kayak and arrive early.

If you’re traveling from the Lower 48, flying may be a good option but requires a folding boat. Virtually all communities are serviced by commercial airlines. Even getting somewhere without a commercial airline is doable with a bush pilot. In Canada, bush pilots are allowed to carry an external load (a hard-shell kayak) with inboard passengers. In the United States, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations do not allow this maneuver.

To contact most of the ferry services mentioned, here is a list of Internet addresses:

One site that consolidates all information: www.ferrytravel.com

Individual ferry sites: www.wsdot.wa.gov, www.pugetsoundexpress.com, www.dot.state.ak.us/amhs, and www.bcferries.bc.ca/

The Bottom Line I: Navigation

A friend of mine (let’s call him Bob Egge, to protect the author) once paddled 500 miles in Ethiopia using a Michelin road map and WWII vintage British Ordnance Survey maps (with all the accuracy of a gambler’s hunch) to navigate. Bob was a good map reader. He had seen two tours of duty in Vietnam as a Marine forward observer. Just prior to and during an infantry assault, a forward observer, armed with map and radio, advances as close as possible to the enemy, often on his belly. With little chance to stand up and survey the territory (sometimes heavily forested and featureless) and always under threat of discovery, he pinpoints enemy troop locations and transmits the coordinates back to the artillery. The artillery then “softens” the position. Before global positioning satellites and modern computers to aim the ordnance, this system was prone to error. Bob’s life and that of his fellow advancing troops depended on the accuracy of his map reading (after all, the distance between opposing factions during an assault narrows to nil). Bob could pinpoint any location, anywhere, with the most rudimentary map and intuitive sensibilities forged under fire. Paddling the Inside Passage similarly requires impeccable map-reading skills. Your confidence, sanity, and life depend on it.

Even if you’re as skilled as Bob, you’ll need more than a road map to paddle to Alaska. Traditionally, sea voyages rely on nautical charts and coast pilots, and so do we as two resources in our arsenal. These focus on marine and coastal features with a smattering of prominent interior landmarks—fine for oceangoing vessels. But kayaks are a coastal adaptation, and kayakers rely on land for sleeping, eating, safety, and even going to the bathroom (by and large). We also need to know the lay of the land, and only topographic maps can provide that. Additionally, a kayaker needs one map of the entire Inside Passage, not only to plot his overall route while planning the expedition but also to keep the big picture in focus while on the water. Add cruising guides, tide and current charts, and specialty maps and you’ll be lucky to have room for food, tent, and sleeping bag. Some serious editing is required.

First, the overall map: R. O. Malin’s two-portion “The Northwest Coast” map, published by the Sobay Company, is widely available, handsome, easy on the eyes, and great for figuring and plotting the entire route back at home. It’s too big and ungainly to carry in a kayak, but it looks sharp hung on the wall. “Alaska & Canada’s Inside Passage Cruise Tour Guide,” published by Coastal Cruise Tour Guides, is an excellent alternative that you can carry with you (plus, it has lots of interpretive stuff on the margins).

Now for the meat. Nautical charts come in a bewildering array of scales. Exactly which one to pick can be mind numbing. Although the largest scale (that which shows the greatest detail) is the most useful, you can’t practically carry them all (nor can your wallet). US nautical charts and catalogs are also available from the source: in the United States, contact Distribution Branch, (N/CG33), National Ocean Service, Riverdale, MD 20737, 301-436-6990; in Canada, contact Canadian Hydrographic Service, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Institute of Ocean Sciences, Patricia Bay, 9860 West Saanich Road, P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, BC V8L 4B2, Canada.

Compromise and decide on a selection that will at least cover your entire route with a mix of some small- and mostly medium-scale charts. Add a smattering of large-scale charts to cover problem areas such as small island archipelagos, congested commercial navigational routes, complex bays and ports, and areas subject to drying at low tides. Another reasonable compromise is the Marine Atlas, volumes 1 and 2, published by Bayless Enterprises, Inc., a complete set of charts in book form at various convenient scales. While not as easy on the eyes and focusing on major cruise routes, and with a sometimes-glaring lack of detail, these are considerably cheaper than a full set of nautical charts.

Topographic maps—both US and Canadian—are published in uniform increasing scale. A full set of the 1:250,000 scale gives good coverage at a reasonable price and volume. Though charts often note the character of the shore, they don’t always at larger scales. Topo maps show stream locations (a must for fresh water) and allow one to infer the shore character from the lay of the land hindshore. Additionally, the 1:250,000 scale (if you shop smartly) will cover alternate routes you might decide on in the heat of the paddle (we changed routes three times and reconsidered a fourth). If expense is a concern—after all, you can spend close to $1,000 on charts and maps—stick, at least, to a full set of topos at this scale, and, if you can afford it, add some well-chosen charts.

US topo maps are available from USGS Information Services, Box 25286, Denver, CO 80225, 1-800-USA-MAPS, as are indices. For Canadian equivalents, log on to the National Resources Canada website (www.nrcan.gc.ca) for regional retail distribution centers and their phone numbers and addresses. For a full list of the 1:250,000 scale topo maps required for the proposed route, see Appendix A. For the really cheap, DeLorme Mapping publishes the Alaska Atlas & Gazetteer and the Washington Atlas & Gazetteer, full bound sets of 1:250,000 scale topographic maps for both states, for only $14.95 each (there is no Canadian equivalent).

Finally, there are a variety of specialty maps that can be more or less helpful. US Forest Service maps of the Tongass National Forest, Misty Fjords National Monument, and Admiralty Island National Monument have some features which are very useful—for example, Forest Service rental cabins (these are available for rent at a very nominal fee, though they require advance booking), public shelters (a bit of a disappointment—they provide shelter from rain, not bears; available on a first-come, first-served basis), and, for Misty Fjords, highlighted areas where it’s nigh impossible to land. All are put out by the USDA Forest Service, Information Center, 101 Egan Drive, Juneau, AK 99801, 907-586-8751.

International Sailing Supply (320 Cross Street, Punta Gorda, FL 33950, 1-800-423-9026) publishes a set of waterproof charts covering Puget Sound and the San Juan Islands that are compact and reasonably priced, with detail insets. (They may now publish more charts of relevant areas.) In Canada, Coastal Waters Recreation had a handful of specialty kayaking maps replete with backcountry campsites, provincial parks, sea caves, government wharves, native reserves, hiking trails, wildlife viewing sites, and so on, for Bella Bella, the Gulf Islands, Desolation Sound, Johnstone Strait, and many more areas. Unfortunately they are no longer in business, but if you can locate some of their old maps, they are very useful. Finally, SEAtrails publishes a series of free, downloadable PDF kayaking maps for a variety of areas along the Alaska Panhandle (www.seatrails.org).

No list of maps would be complete without Stephen Hilson’s two-volume historical atlases of the Inside Passage, Exploring Puget Sound & British Columbia and Exploring Alaska & British Columbia, both published by Evergreen Pacific Publishing Ltd. These are actual charts (though technically not for navigation, as their information is not updated) reconfigured into book form, with a good color scheme, profile pen-and-ink drawings, and aerial color photographs. But the real purpose of these volumes is the etymology of place names and the history associated with the sea and landforms. Want to find out something about the Sukoi Islands just north of Petersburg? Open the folio to the appropriate chart and you’ll find: “Fox farms on Big and Little Sukoi operated in 1923 under the name of Sukoi Is. Fox Co. Sukoi is Russian word for dry.” This information, aside from its intrinsic value, implies that not only is a landing possible here, but that reasonable camping may be available as well. The texts are printed right on the charts, using shores as margins.

On top of every successful map lies a compass. Sea kayakers need two. For technical orientation, especially in mini-archipelagos of similarly shaped and sized islands, where disorientation can occur for absolutely no reason at all, a good handheld compass is a must. It helps if the compass comes equipped with a bearing-sighting notch in conjunction with a mirror so it can be held up for an accurate sight-reading. Also indispensable, both for target fixation and gauging drift, is a deck-mounted compass. There are many models, some more readable than others. Make sure yours is mounted in such a way as to enhance its readability.

Indispensable for on-board navigation is a homemade tool I call Rosie. I do all my navigation off magnetic readings; I never correct for true north, as I would invariably befuddle myself and make mistakes. Rosie is a small compass rose copied from a chart onto a rectangular plastic transparency. Additionally, along one edge, I inscribe a mileage scale from a 1:250,000 topo map. Rosie should depict magnetic bearings prominently, while her up- and downsides ought to align with true north so she can be easily aligned with longitude lines on the map. Rosie has a sister named Audrey (after Audrey Sutherland, her inventor). Audrey is a transparent gallon-size baggie with parallel lines drawn across it every 5 miles (again, scaled from a 1:250,000 topo map) with an indelible marker. Audrey serves as a set of foldable, disposable parallel lines for setting courses and doubles as a portable scale (remember that scale varies on charts so either have more than one Audrey for different charts or read distances only from the 1:250,000 topo map). Audrey can store Rosie. Commercially available Rosie-Audrey combos are known as “coursers.” (For a detailed discussion on the construction and use of Rosie—with a photocopiable compass rose—see “The Kayaker’s Course Plotter” by Dennis Fortier in the December 2003 issue of Sea Kayaker.)

There are many more aspects to kayak navigation in addition to map reading. David Burch, in Fundamentals of Kayak Navigation, covers them all. We carried his book on two legs of our trip. Few can master all the tricks and techniques he discusses—not all are essential, and many are completely unnecessary when in view of highly featured terrain. Starting in Puget Sound is a good strategy if in the least bit of doubt about your navigational acumen: you can always resort to the ignominy of asking for directions. GPS is no substitute for ability. Though I own one, we never carried it. It really comes into its own in featureless terrain (always stay within sight of shore), during blind—fog or night—navigation (ditto), when requiring pinpoint precision (you’re not digging for treasure or directing mortar bombardment), and, if in doubt, to verify your position. But if you need a GPS to verify your position, your skills are inadequate for kayaking the Inside Passage.

The Coast Pilot (Sailing Directions in Canada) may seem like a quaint eccentricity to those brought up on terrestrial navigation. Just exactly what is its function? Do we really need a running commentary on the marine cartographer’s work? In his The Log from the Sea of Cortez, John Steinbeck wrote:

In the first place, the compilers of this book are cynical men. They know that they are writing for morons, that if by any effort their descriptions can be misinterpreted or misunderstood by the reader, that effort will be made. These writers have a contempt for almost everything. They would like an ocean and coastline unchanging and unchangeable; lights and buoys that do not rust and wash away; winds and storms that come at specified times; and, finally, reasonably intelligent men to read their instructions. They are gratified in none of these desires. They try to write calmly and objectively, but now and then a little bitterness creeps in.

Notwithstanding the sardonic commentary, Steinbeck admired the terseness of the Coast Pilot prose, which—besides dealing with navigational details (such as shipping lanes, local customs, rights-of-way, Customs procedures, etc.) and variable conditions not reliably rendered on charts—gives a succinct, technical summary of weather patterns (and extremes), tidal and current advisories, verbal descriptions of coastlines, protected harbors, and port descriptions. Coast Pilot is updated annually, on a more regular basis than charts. Unfortunately they are promiscuous. Written for every type of craft, from a kayak to a supertanker, they take on all comers. Without a Coast Pilot, commercial shipping (and the mobility of anything larger than a skiff) would be seriously hampered. Fortunately, kayaks can slow down and reverse faster than a dreadnought, won’t sink when colliding with a reef, don’t suffer prop damage when impaled by a deadhead, and are usually dry-docked overnight. Before (figuratively) weighing anchor, at least read the relevant volume, highlight information you might find helpful, copy it, condense it, and take it with you.

More useful for the kayaker, because they’re written for small, mostly recreational craft, are the privately published cruising guides such as Charlie’s Charts North to Alaska by Charles E. Wood, A Cruising Guide to Puget Sound by Migael Scherer, and the multivolume Northwest Coast series by Don Douglass and Reanne Hemingway-Douglass. These mostly incorporate the pertinent Coast Pilot information, delete the mostly—from the paddler’s perspective—irrelevant material, and greatly expand on stuff definitely useful to the kayaker. Overall, the Douglass guides are the most informative and may merit being taken along (we did, though selectively edited). Charlie’s Charts North to Alaska is strong on ports and rapids sketches—definitely a useful feature.

A variety of general outdoor activity and strictly paddling guides have also been published for selected areas of the Inside Passage. These cover the gamut from what to do, to where to stay, to where to eat and what to see. The majority of paddling guides, in addition to covering discreet portions, are organized in “loop-trip format,” mostly short loop outings with detailed information on access, camping, and return. For a list of these and other references of even more limited scope, check the bibliography.

The good news is that “Tide Tables,” in a 3-by-5-inch booklet, are complimentary at marine retailers in Alaska. In Canada, you’ll have to buy them along with current tables. For Puget Sound, both are available at the many kayak shops in the area. Current tables are particularly important in the San Juan Islands and Desolation Sound. Tidal flows move away from and toward the Pacific, into and away from shore. Tidal height variation and current strength increase in proportion to the distance from open ocean and constriction of the passage up which the water must travel. A good example of this phenomenon is the head of navigation in the Sea of Cortez, where the Colorado River delta is located. Tidal heights at Ensenada, on the open Pacific, are minimal, while at San Felipe, directly across the peninsula in the Cortez, tides rise more than 20 feet. This is because during the six or so hours that the tide rises a foot at Ensenada, it must duplicate the same feat at the head of the gulf, negotiating the length of the Baja Peninsula and the constriction of the Midriff Islands in the attempt. So, to compensate, the tide rushes in at a much greater speed. But it has no brakes, so it overcompensates and piles up (late, since the obstacles succeed in delaying it) at its destination. Then it must duplicate the process in reverse when departing. The tide only slows and stops when it accomplishes its goal—being in or out. This respite is known as the “slack.”

One might then logically conclude that slack water would therefore always coincide with high or low tide. And in a perfect world—and some real locations—that is, in fact, the case. Unfortunately, geography and hydrodynamics complicate matters in counterintuitive ways. A good analogy is a person taking a bath. If he or she moves forward to adjust the hot/cold water mix, their torso pushes a pillow of water forward, creating a “high tide.” Instantly, the two narrow spots adjacent to their hips lower significantly, and water rushes in to fill the voids. At their lowest point, the voids experience no slack, as water constantly rushes in to equalize levels. So, in the real world, what is the relationship between tidal extremes and slack? During neap tides, tidal extremes and slack tend to coincide; during spring tides, because of the greater volumes of water being exchanged, slack will typically trail high and low tide, sometimes by as much as an hour.

A neap tide is one in which the difference between high and low tide is the least, while a spring tide is one in which the difference between high and low tide is the greatest. Spring and neap tides occur twice a month, with the highest high and lowest low appearing at or near the summer solstice on June 21. Full and new moons produce the highest tides. Neap tides occur when the sun and moon are at right angles to the earth. When this is the case, their total gravitational pull on the earth’s water is weakened because it comes from two different directions. On the other hand, spring tides occur when the moon, the sun and the earth are all aligned like a billiard cue. In this case their collective gravitational pull on the earth’s water is strengthened. Nearly every day there will be a higher high tide and a lower high tide, as well as a lower low tide and a higher low tide.

When tides collide with an oblong island lying perpendicular to the inflow (as at Vancouver, Princess Royal, and Pitt Islands), they split and do a flanking maneuver around both ends. Exactly where they meet (see the current tables) will determine where the current reverses. Some spots are downright weird. In some channels the current always flows in one direction—for example, Colvos Passage in Puget Sound. We found this to be the case in Griffin Pass, a narrow channel on the central BC coast. Though technically “uncharted” due to its inappropriateness for craft larger than kayaks, it is still worth traversing for its shortcut and isolation. (The exact nature of its tides and currents await a modern-day Vancouver).

It is better to go with the current than to buck it. But if you have to buck it, buck up; it’s often not as bad as it’s been made out to be. By and large, most locales are subject to flows of nil to 2 knots current; a few, 3 to 4 knots. Many are manageable by working the shore, nearly always scalloped (sea kayaking is best along shore, anyway), where the flow is slowed due to friction against the land and even reverses sometimes due to the formation of eddies. Our experience, over a day’s paddle, was that one hour more or less, or a bit more exertion (or coasting) was negligible—just part of the trip. A very few places dictate when you can paddle, and at these you must work with the current, or actually avoid them. Seymour Narrows has currents clocked at 16 knots. Yuculta, Whirlpool, and Greene Point Rapids, in Desolation Channel, must be timed for slack water. Many channel crossings also either require a strategy—such as bracketing the slack, or even ferry gliding (Portland Canal, for instance)—or at least an awareness of what the tides and currents are up to.

When winds mate with currents, sea states metamorphose. Downwind currents have their swells minimized by the flattening effect of the breeze. Conversely, when wind opposes current, wave frequency is shortened; waves steepen, froth, and break. Under both situations, sea states are at variance with one’s intuitive expectations. These conditions achieve exquisite hellishness at headlands where currents converge or separate, creating tide rips.

Rips are first sensed as a low roar, like an imminent rapid. The waves become irregular and pyramidal, leaping up and disappearing chaotically. Take evasive actions so as to avoid them. If you cannot avoid the rip, head straight through it, paddling hard à la Major Powell to maintain balance.

The worst current conditions are encountered at major outflow channels. Extensive marine incursions, such as Portland and Butte Inlets, suck in and disgorge huge amounts of water during the tide cycles—time your major inlet crossings with slack tide. But even more catastrophic are the outflow deltas of big rivers. The Skeena River, for example, dumps a continuous and unremitting volume of discharge into the Pacific. There is no slack. Eddy lines, with gargantuan whirlpools, can measure 50 feet or more across. Opposing currents clash and can cause aggregate differentials exceeding 8 knots, unpredictable wave flourishes, and a maelstrom best avoided by choosing a route far from the constriction of the channel proper, well at the verges of the delta’s funnel mouth.

More than once during our journeys, we dreamed we were floating the Inside Passage, only to wake up and find it was no dream. At least three times we woke up bobbing on our Therm-a-Rests, wondering what the world had come to: our campsites had been flooded by the wee hour’s high tides. It was an undignified, disoriented, and naked scramble to move the tent and retrieve our paraphernalia—an ordeal better prepared souls ought to avoid. Just refer to the article “Gauging High Tides: The Rule of 12s” by Bob Hume in the June 1999 issue of Sea Kayaker. Hume presents a rule-of-thumb approach to estimating how high the tide might encroach at any one particular spot when somewhere betwixt high and low tides. Though this is not easily committed to memory and calls upon full concentration when all you want is a place to sleep after a miserable day of paddling in full conditions, better to have it and compute your situation than not (see page 168).

Back home, a watch is unnecessary; out where the blade meets the swell, it is an essential navigational tool. Gauging tides for one, and determining slack—which at Yuculta Rapids opens a window of opportunity only minutes long—is impossible without a watch. Dead reckoning would be truly moribund without a timepiece. Sometimes while paddling along a featureless shore, ensconced in a downy quilt of fog (say near False Head on the north shore of Vancouver Island), the only way to gauge progress is by counting the hours of steady paddling. Crossing straits wider than 2 miles is a test of faith without a watch. If you can, carry a watch with a few bells and whistles. Alarms are great for catching early tides. Waterproofness is de rigueur. I’d wear mine on my kayak’s deck bungee so it wouldn’t interfere with the dry suit gasket or chafe my wrist. There I could glance at it without breaking rhythm, and its thermometer could measure air temperature without the influence of a warm body. Whenever we approached glaciers, the chill was noticeable. Passing McBride Glacier, my hands went numb; the temperature had dropped 16° to 48°F.

The barometric tendency line on the Suunto altimeter watch is a great wind and rain predictor. It shows the barometric pressure trend for the previous six hours, with the trend for the last three subject to a separate indicator. If it was clear with a northwesterly breeze, and the second half of that little indicator line went limp, the wind, without fail, would calm or back around and the humidity would hit dew point within the hour. If both sides of the barometric tendency line pointed down, it was time for a real weather report.

The Bottom Line II: Safety

A VHF radio is a handy gadget to have along, especially now that new Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulations have made them simpler to own and operate. During wretched evenings we’d gather round the console like Depression-era families hanging on to FDR’s every word in hopes of better prospects for the morrow. Of course, you can just carry a weather radio, but these don’t seem as powerful as a good VHF. When only receiving, a battery charge lasts about two weeks, so we brought along an AA battery adapter and spare batteries. During transmission, power consumption is much greater, and, particularly for Luddites like us, manipulation is much more complicated. But if you can master the button-pushing/releasing, talking/listening sequence; the stylized jargon; and the self-conscious trolling for strangers monitoring their radios, you too can transmit over the airwaves. You can even make telephone calls through a marine operator. That tenuous electronic link with the outside world can be a real lifesaver, but don’t depend on it. Although the coast is peppered with relay stations, often only line-of-sight communication is dependable (great for contacting passing traffic). Transmission and reception both improve with altitude and proximity to settlements. See Appendix C for basic marine radio protocol for kayakers.

Cell phone coverage is very patchy, subject to overlapping jurisdictions, and won’t provide a weather report. Satellite phones are a better bet. Not much larger than ordinary cell phones, Iridium satellite phones (the original pioneer), now joined by many other brands including Globalstar, Thuraya, Inmarsat, and others, provide full coverage anywhere and anytime for a reasonable price (including rental vs. purchase). For an introductory lowdown on these, see Gary Lai’s “Keeping in Touch from Anywhere: Two Affordable Handheld Satellite Phones for Sea Kayakers” in the December 2003 issue of Sea Kayaker. Nonetheless, electronic technology and seawater don’t mix well; the prudent paddler will rely primarily on himself.

Since logging a float plan with the relevant authorities is impractical, your first line of defense must be a prudent and conservative approach to potentially dangerous situations (note the quote at the heading of this chapter): Stay out of trouble. Your second line of defense is to stay upright. Next is an absolutely bombproof Eskimo roll. In my opinion, like the admonition concerning navigation skills, don’t go if you can’t roll. That was the logic behind the roll’s invention. Inuit hunters never, ever left their boats, because the consequences were just too dire. So they developed rolls for virtually any predicament into which they might be cast. These ran the gamut from assisted rolls (other kayaks or device-aided rolls), through various paddle rolls, to hand and body English rolls. Modern kayakers can profit from this approach.

Conventional river kayaking emphasizes the screw (or C-to-C) roll because it’s quick and doesn’t require hand placement changes. With a small, light boat, close to shore, failure is no big deal. Just try again. In a fully loaded sea kayak, with deck impedimenta resisting your efforts (God knows how far from land) and the panic of impending doom overwhelming your already strained disposition from battling gnarly conditions, the screw roll is not my first choice. If you go over, you must get up; if not on the first attempt, you’ve got to have the confidence in your system that allows success very soon. First, ensure you and your kayak are as tightly mated as an abalone to its shell; a kayak is virtually uncontrollable if you’re lounging in it as if it were a bathtub. Then, go as light as you can and carry nothing on your deck. I realize that this is easier said than done, but some compromises are possible. Say you normally carry spare paddles, charts, a pump, a tow/rescue line, and a deck bag on top (if you have other gear on deck, get a bigger kayak). At least make sure the deck bag is small, not floppy, hydrodynamic, and bound to the deck like a limpet; that way, if you have to roll, it won’t thwart your efforts. If you purposely take a calculated risk and head out in questionable conditions, clear the decks and stow everything inside. After all, bigger boats do the same, and, as Louis Pasteur once said: “Chance favors the prepared.”

The trouble with the screw roll is its poor leverage and indeterminacy of blade angle. So I prefer a different approach: get the most leverage by using the entire length of the paddle and position the blade exactly, for the most resistance, by holding the blade in your hand and adjusting its precise angle. These types of rolls—there are many—are generically known as extended paddle rolls. I favor two: the Pawlatta, for its ease of execution and similarity to the screw roll; and the put-across, because it’s the only paddle roll I find intuitive. One resource that has merit is “The Vertical Storm Roll: Trick or Skill?” by Doug Alderson in the December 2001 issue of Sea Kayaker; and for a more intuitive, visual experience, there are a handful of YouTube videos accessible via a web search worded “sea kayak Eskimo roll video.” Even if you master these rolls, some additional aids are available, and I’ll review them here because, like the Inuit, I believe exiting the boat is out of the question.

The Petrussen Maneuver. This is a fancy name for a very simple technique that allows a kayaker to get a breath while upside down. It requires dislodging oneself from the viselike grip of your fit by pushing slightly away from the seat, twisting the body sideways around the capsized kayak, and then raising the head above water to breathe, cry out for help, or wait for an assisted roll. For a detailed description, see Greg Stamer’s article, “The Petrussen Maneuver: A New Twist on an Old Technique” in the August 2000 issue of Sea Kayaker.

Assisted Rolls. Assisted rolls have a long pedigree in rescue instruction but are rarely if ever used. I suspect they evolved as a response to capsizes due to Inuit hunting mishaps. In calm water, with other hunters nearby, the assisted roll was a viable option. In modern sea kayaking, capsizes are due to violent conditions. Violent conditions require full concentration and necessitate a greater spacing of paddling companions to allow for unimpeded maneuvering, thereby rendering an assisted roll more improbable. The Petrussen Maneuver could prove useful in these conditions.

Air Bladders. Another takeoff on Inuit ingenuity is the BackUP by Roll-Aid Safety Inc. Inuit hunters carried an inflated seal bladder on deck, attached to the harpoon, to prevent speared game from escaping by diving. This rendered retrieval a snap. In the event of capsize, the bladder also provided rescue buoyancy. The BackUP is a compact, CO2 cartridge–activated nylon bladder that can be carried on deck unobtrusively and inflates in seconds. Just deploy, place your hands on the 80 pounds of buoyancy, pull up (or hip flick), and you’re up. It is reusable with a new CO2 cartridge. For what to do in the maelstrom with the resultant beach ball, consult the instructions. Although we both have a variety of dependable rolls, we each carry a BackUP. Roll-Aid is no longer in business, but you might find the BackUP in a secondary market.

Sea Wings/Sponsons. These are essentially air-filled outriggers attached snuggly right behind the cockpit to stabilize a kayak for reentry after a dump. Though not practical to have attached while en route, they can be attached after a wet exit, inflated, and the kayak reentered more stably. They are somewhat controversial, with proponents including John Dowd, Wayne Horodowitch, and Dennis Dwyer; while others ridicule them as troublesome, ineffective, cumbersome, and impractical. Perhaps that’s why Harmony Gear (www.harmonygear.com) has discontinued them. However, they may be available later, elsewhere, or homemade.

Underwater Supplementary Air Devices. Back in the 1970s someone came up with the idea of using the fetid air inside a kayak to extend the time a paddler could spend upside down. This was accomplished by extending a flexible rubber hose from an opening in the sprayskirt to the mouth. At the sprayskirt, the hose had about a 2-inch rigid end that extended through the neoprene so that, when upside down, any puddle of water in the kayak would not be aspirated. The seal consisted of off-the-shelf PVC screw fixtures with plastic washers. The mouth end was a snorkel bit. You could unscrew the hose and cap the rigid tube if you did not require it deployable, or you could just keep the whole thing on the sprayskirt and out of the way under a bungee. This device requires a tight-fitting (torso-wise) spraydeck. It was marketed for a short time and died an unsung death, probably because it was aimed at the whitewater market. It wouldn’t be hard for the do-it-yourselfer to reinvent, perhaps not by attaching it, but simply by placing the hose through the sprayskirt tube against the paddler’s chest. That way the mouthpiece is always close to the chin. An EPA analysis of cockpit air quality is still pending.

Yakerz! used to market a refillable air bladder that attaches to the PFD. The KUBA (Kayaker’s Underwater Breathing Apparatus) was a supplemental air system designed to decrease water acclimation anxiety by providing one to ten breaths with hands-free access through a standard hydration-system bite valve. It could be refilled on the spot and retails for $159. Unfortunately, Yakerz! seems to have disappeared. But the idea of the KUBA has merit and may soon be resuscitated under a different guise. See also Chris Cunningham’s review in Sea Kayaker, October 2002. Rapid Air also markets an emergency air supply that provides 15 to 20 breaths, is very compact, and refillable from a compressed air source. It is available from Rapid Products, Inc., at 303-761-9600 or www.rapidair.net.

This is as good a place as any to mention nose plugs. Before you dismiss them as totally déclassé, consider that none other than Derek Hutchinson, one of the great expedition sea kayakers, is an advocate of their use. They weigh nothing and are totally unobtrusive worn around the neck. The only way, sans nose plugs, to keep water out of your nose while upside down is to exhale precious air. Not a good strategy when dumped unexpectedly. They can be attached during extreme conditions, prophylactically, in anticipation of disaster.

Reentry techniques after an exit are a last resort. There are many, assisted and unassisted, with and without aids. Learn the ones appropriate for your boat but don’t depend on them. I cannot emphasize enough: Don’t exit your kayak unless you’re close to shore and braving the surf is the easier option. Conditions that flipped you don’t facilitate reentry.

Tina and I had drifted apart. Not metaphorically, but purposefully and determinedly. We were crossing the junction of Frederick Sound and Stephens Passage, between The Brothers and False Point Pybus on Admiralty Island. Morning had dawned calm and foggy. We set out. Currents are known to do strange things at points where they split or converge. Never mind that the map labeled this a “false” point. Then the wind picked up, against the tide. With the currents mixing, the wind in opposition, Pacific swell impinging, and clapotis adding to the anarchy, a large portion of sea looked like a punk hairdo moussed by a drunken stylist. The trough-to-crest height (not that this was clearly discernible, what with rogue wind and regular swell adding to the confusion) was only 6 to 8 feet. But the currents were stronger than we were, and the chaos required the reflexes of a boxer. We tried to bore away at sprint speed but were ineluctably sucked in. So as not to collide, we put more distance between us after a fleeting, knowing glance. Every stroke was a compromise between staying upright and making headway for shore. Time dissolved.

“I was sure I’d have to roll,” Tina blurted when she hit the beach.

“Me too,” I retorted.

Having a bombproof roll provides the confidence necessary to tackle such conditions and to execute braces with total commitment, not half-hearted lily-dips. During the entire trip, we never had to roll, but the self-assurance instilled by its integration into our tool kit enabled us to face many a planned—and unplanned—situation.

The Bottom Line III: Seamanship

When the ancient Germanic tribes that would become the Angles and the Saxons were confronted by a novelty, instead of making up a new word to describe it or borrowing a word from a neighboring tribe, they would join old words to form a new, compound word. Whale + road = whaleroad = sea. Likewise, Old English took sea + man + ship and created seamanship, a word whose meaning is neatly summed up by the three individual concepts in sea, man, and ship, but implies much more. Seamanship is the characteristic that describes the successful adaptation of an individual to the marine environment through the use of a boat.

For the sea kayaker (as for any mariner), seamanship means proficiency in the operation of your craft and knowledge of the stage upon which it performs—the sea. Exercise of the two in tandem yields experience, which in turn is maximized by self-knowledge and common sense. A highly developed degree of seamanship often expresses itself intuitively. But don’t be fooled; always check your intuition with reality—it can only make you wiser.

Your seamanship needs work if your weather predictions are no better than a crapshoot; if waves and clouds, like penguins, all look the same; if you can’t talk and stay the course at the same time; if your dead reckoning is way off not only in distance but also in direction; if boat wakes panic or even capsize you; if it’s always a revelation what the tide is doing; if you need to ask directions from passing boats; if you need to ask directions from passing boats but refrain out of fear of ridicule; if you are disproportionately plagued by rotten luck; or if you don’t know the difference between a guyot and a gyre. So, what degree of seamanship is essential for kayaking the Inside Passage? There are no absolutes; seamanship is a journey, not a destination.

Bears

You will encounter two species of bear: grizzly (Ursus arctos horribilis) and black (Ursus americanus). If you’re very lucky, you may encounter a subspecies, the white (not albino) Kermode (Ursus americanus kermodei), a variant of the black bear most common on Princess Royal Island. Though they are technically the same species, brown bears are the coastal complement of grizzly bears. Adaptation to a different environment has created differences in behavior and size: incipient speciation. The coastal brown bears subsist on a rich diet of berries and fat-flush salmon, gathered from a crowded littoral; consequently, they are larger yet more tolerant of each other, requiring less territory per individual than their inland relatives. Some giant males on Kodiak Island can weigh as much as 1,400 pounds, though on Admiralty Island they seldom exceed 700 pounds. At Yellowstone National Park, a grizzly requires about 500 square miles of forage territory, nowhere near Admiralty Island’s tolerant density of one bear per square mile.

Much has been written on bear behavior, bear attacks, and bear safety. Read it. (The best of the lot is Bear Attacks: Their Causes and Avoidance by Stephen Herrero.) I’ll confine my comments to my experience, reliable anecdotes, and the conclusions of my unplanned research. Though the two species’ behaviors and habitats differ, for practical purposes, mitigation of encounters is about the same. We encountered more black bears than grizzlies along the Inside Passage.

Bears are very much like humans in that their behavior varies according to their nature and nurture, and can vary tremendously from individual to individual. So prepare for anything. This said, there are four broad categories of bears:

Wild Bears. These are the bear equivalent of Rousseau’s natural savage. Most bears fall into this category. Most of the material written concerning bear behavior applies to these bears. If you’re a good camper and follow all the bear camping rules, you’ll have little problem: for instance, give plenty of notice concerning your presence and do not make food a point of contention with Mr. Bear. Most wild bears will leave you alone and avoid potential trouble. The more curious will follow suit after a more cursory smell-over.

black bear

People-Accustomed Bears. These bears like to mingle, though many may lack social graces. They are the ones often found in national parks such as Yosemite and Yellowstone. To them, people are little different from trees. They’ll mostly leave you alone and are totally blasé about your presence. The only likely locales for these bears are the Pack Creek and Anan Creek Bear Observatories, Glacier Bay National Park—especially on the Beardslee Islands—and perhaps in developed campgrounds. A very thin line separates people-accustomed bears from the next category.

Food-Accustomed Bears. Luckily, the NPS authorities (in the park alone, of course) have done an excellent and very successful job of managing human behavior so as not to create this type of bear. A food-accustomed bear has either been given a handout or has discovered, on his own (due to either bad camping behavior or improper garbage disposal), people food. This bear will walk through you to get food or what he expects to be food. You’re in trouble only if you give him food, on purpose or inadvertently, or if he thinks you’re holding out. Public authorities exile these bears when they get too aggressive. You might run into them close to settlements or fish camps.

Bad Bears. These are rare. One grizzly, in Montana, had acquired the reputation of attacking, and maiming or killing, any living thing he ran into. Yet his behavior was not hunting per se, as he’d abandon the kill site. Not at all like a typical grizzly (they don’t even hunt people). After one too many sprees, he was finally hunted down and killed by the authorities. The necropsy revealed an ingrown tooth. Poor bear, the pain must have turned him into a bully. But it’s not the grizzly that makes a good bad bear candidate—it’s the black bear that can develop a taste for human prey and actually stalk and kill people. A recent Canadian study indicates that, of the black bears that are prone to hunt humans, male black bears are the primary culprits. Watch out for disingenuous, macho black bears.

So should you take a gun? Pepper Spray? A rubber President Nixon mask? I’ve never had to use the first two and had great results with the last. To kill a bear you need a big gun, and it must withstand the rigors of kayaking in the Northwest. Since handguns are illegal in Canada and a .44 Magnum would be strictly a mano-a-mano last resort, the gun of choice seems to be a stainless-steel, 12-gauge shotgun with as short a barrel as you can get away with and a capacity of five to seven solid slugs. The problem is that, inside a small dome tent, with a bear tearing through the wall—admittedly an improbable scenario—a shotgun just doesn’t have the turning radius of a handgun. Any gun is an absolute last resort. Shooting a bear when it is charging at you is not recommended. Most Alaskan bears’ skulls will deflect a .45 caliber bullet. And bears are vindictive and ill-tempered when shot. The bear almost always lives long enough to maul the shooter severely. If you do take a gun, think of it as protection for your buddies, not yourself. Whatever you choose to take, you must always have it at the ready and know how to use it, both safety-wise and for effectiveness.

Dances with Bears I

Once, while portaging a waterfall on the Thelon River in the Northwest Territories of Canada, I tired of lugging the damn shotgun on every single carry (there were many). We had decided to break up the portage into relays and, for the first relay, were stockpiling gear atop the escarpment that defined the river channel’s gorge. We would then do a second relay and negotiate the steep final descent down to the put-in eddy. After doing the penultimate trip down to the river, we trudged back up for one more load. Suddenly, I turned to Martha, my companion: “Look!” I screamed in a whisper.

There, only about 20 yards above us (it was a good 45° slope), stood a black bear, enthroned among the blueberry bushes, with a foot-long purple drool swinging from his mouth, legs splayed atop my shotgun like the Colossus of Rhodes. We backed away slowly just as every bear-warning pamphlet advises (never turn your back to a bear!), and decided to execute a very wide and slow end run around the spot. Luckily, he didn’t give chase. We were hoping that, by the time we circled around, he’d have moved on. On our second (and much delayed) approach, this time arriving in a different spot—against all odds—he surprised us again. Martha panicked and ran. The bear charged. I was right in his path.

It wasn’t a malicious charge, nor did it seem premeditated. It was instinctive, automatic. Instead of my life flashing before my eyes, all the potential lovers I had ever known but never consummated flooded my mind. At the same time, my mind reviewed all the possible effective strategies I could now call upon. Warrior mode took over. I put on a terrifying face, waved my arms, screamed, and countercharged. The bear ran off. The Nixon mask worked.

This is supposed to be a good strategy, in extremis, for dealing with a black bear. Not so with a grizzly. If these charge, at best it’s a bluff: he’ll stop short of you or run past you. Make not a sound, cower, give up, and assume the fetal position to protect your vitals. At worst, he’ll thump and scratch you—no small thing. Just don’t resist.

Pepper spray is the repellent of choice for Parks Canada rangers. But it takes guts to deploy, because you trigger it earlier than you intuitively think you ought to. Spray before a charge (nothing can stop a charging grizzly at close range). Bears will usually echo- and olfactory-survey the scene (rumor has it they’re myopic), often standing up to do so (mainly grizzlies), and swing their heads back and forth. Avoid eye contact. Remember that this is considered aggressive behavior in the animal world. (Actually, bears have damn good eyesight, and this combination of behaviors is now believed to be the bear’s way of integrating visual, olfactory, and auditory clues into one seamless whole.) Spray now. The objective is to have the bear inhale a bit of the capsicum to irritate his mucus membranes. If he does, voila, he’ll turn and run. But consider two things: proximity and wind strength/direction. Getting pepper spray on you is harmless (just as for the bear) but a hell of a bad trip. At least you know it can’t hurt you. Rinse with water.

Bear avoidance is a lot better than bear evasion. Do you announce your presence or keep a low profile? When hiking, the former; when camping, both strategies should be taken into account. Never hike in dense ground cover, and always make plenty of noise. Don’t rely on ineffective little bells: sing loudly, argue politics, or recite, fortississimo, your best rendition of “The Cremation of Sam McGee.”

Camp in an unobtrusive and open place—from the bear’s point of view. No scat, no dug-up holes or turned-over rocks, and no bear trails or scratching trees (an obvious way they mark territory). An unobtrusive spot lacks a stream, often a corridor for his rounds. Points and peninsulas are better than bays. Because all coastlines are more or less scalloped, when bears work the shore, they’ll have a tendency to straighten out the irregularities, especially around rocky or distant promontories. This will give them a chance to become aware of you and avoid you. Or camp on a rocky shelf along a shore that is not conducive to beachcombing (see photo on page 48). Better yet, camp on small islands, far from larger landmasses. And even better yet is to camp on a small island close to a seal or sea lion colony. Pinnipeds and bears seem to have worked out a détente as to where each hangs out. Though bears swim well, distance, orcas, and the magnitude of the enterprise make it slightly less likely that they will. And never camp anywhere near any dead animal or close to a berry patch!

Dances with Bears II

Kent, a Canadian game and fisheries warden, tells the story of one hapless grizzly attempting to swim a channel. The distance was, perhaps, less than a mile. Mr. Bear was beavering away at the swim. Up the channel, the dorsal fins of a small pod of orcas sliced the water—two bulls, some females, and get. The whales spotted the bear first. The moms and pups held back while the bulls circled in. The bear weighed his options. First he looked to the far foreshore and then he looked to the backshore. He rubbernecked back and forth. Realizing both were too far, he tried to paddle straight up like a missile coming out of a nuclear sub. The whales did not circle (after all, they’re not sharks) and did not sprint. They simply swam straight for the grizzly. In seconds, Mr. Bear turned into a red oil slick.

shelf camp, admiralty island

Food, of course, is a major attraction, and great care must be taken with it. It seems as though most bear warnings are predicated on the camping habits of high-impact campers: great big slabs of meat and bacon sizzling on a barbecue and lots of freshly caught fish with offal everywhere. Sea kayakers don’t really fit that mold. We took dry goods double wrapped in Ziploc freezer bags, gravy packets, tinned meat, and Mountain House freeze-dried meals. If you score a salmon, pack it in a Hefty-type plastic garbage bag, clean it well before camp, and, preferably, boil it. Burn the Hefty bag.

Dances with Bears III

We’d just come out of Cordero Channel. It was late. There were no campsites, just vertical rock with forest at waterline. Tina pulled out her binoculars to check a small bay across the sound. It looked promising, so we headed there. The little bay had a small stream at its head and a shingle beach that would accommodate a tent above high tide. It looked to us like prime bear diggings, but pickings were slim, and there was no scat. We pitched the tent. To announce our presence, we built a roaring fire, pissed around the perimeter, and even defecated, near waterline, at the far ends, where we also pulled up the boats. All the gear and food was packed in the holds. We retired with the shotgun nestled between us.

About 2 AM, intuition awoke me. About 30 yards away, a black bear was fiddling with a branch in the shallows. He’d walked right over our boats to get to where he was. I put on my shoes and a scary face, exited the tent, lifted my arms in the V-for-victory sign, and gently urged him to beat it. After turning to me and seemingly mulling it over, he scampered away. Score two for the Nixon mask. I didn’t sleep much after that. Fortunately, he didn’t return.

Dances with Bears IV

Early August. A white sandy beach. I was laid up with a bad back in our North Face dome tent. The shotgun lay between us, and we lay absolutely naked on top of our sleeping bags. It was a sweltering and, this being the northern latitudes, not very dark night. The no-see-um netting zipper had given up the ghost, so the ripstop door was closed, blocking any possible breeze. Tina leaned over and whispered, “There’s someone outside the tent.”

“See who it is,” I smart-assed back. With the door closed, there was no way to see out. Then I heard what sounded like the grunt of a pig right next to the fabric of the tent wall. Tina was terrified (it was on her side). I had wrenched my back and was in the land of lumbago and Percocet. Suddenly our guest thumped the ground loudly and repeatedly, not 18 inches from poor Tina. And then he did it again. It had the same rhythm as a gorilla beating his chest. We cringed quietly. After what seemed like ages, the presence left. When we finally gathered the courage to go out, there, right next to Tina’s side were the paw prints of a huge mama grizzly, as clear as only damp sand can preserve. About 20 feet away were the cub prints.

A few details of these incidents bear noting. Our food, already described, besides being stored in the bulkheaded compartments of the kayaks and double Ziploc-bagged, was liberally peppered with mothballs within rubberized waterproof bags. Either they didn’t smell the food or they were a fifth sort of bear: the retarded bear. Either way, we’ll always take mothballs (bear balls) with us. The theory behind their use is that the strong, piercing smell masks food odors. Just don’t put them adjacent to food, as the essence is contagious and makes the affected item inedible. Not only were the bears oblivious to the fire, our visual presence, and body waste (in the first incident), but even Tina’s menstruation (during both events), an often-noted aggravating circumstance, did not seem to deter or unduly attract. Still, I wouldn’t advocate food storage in kayaks while at camp. The risk is too great. Late in the trip we reverted to the more conventional bear canisters cached a distance from camp and slept much more peacefully.

Thinking more creatively, Dennis Dwyer, in his 2016 Alone in the Passage: An Explorers Guide to Kayaking the Inside Passage, suggests carrying Critter Gitter infrared motion detector alarms designed to scare away animals (or at least awake the camper when set off).

A whole new concept in bear protection was recently introduced by Sureguard Fencing (www.sureguard.com.au), an Australian company: a portable, lightweight, compact, 6,000-volt electric fence kit. The National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) has even tested the kit around tasty cattle carcasses with complete success.

Pinnipeds

Pinnipeds come in three varieties, roughly: seals, sea lions, and walruses. Not a day will pass without a visit from a Pacific harbor seal. These are so ubiquitous that a day without one would be an omen that something in the world is amiss. Less common are sea lions. Both Steller and California sea lions are present. The Steller sea lion ranges along the entire Inside Passage. Though threatened, its population is stable, while some colonies, particularly in Glacier Bay, are thriving. Male California sea lions can range as far north as the southern coast of Alaska, while females remain near California rookeries year-round. Sightings along the Inside Passage are infrequent but increasing. If you see a walrus you’re off route.

indian island harbor seal

Seals lack external ears; males and females are indistinguishable at a glance. Locomotion on land is an ungainly, undulating, caterpillar-like heave. Harbor seals are quiet—sometimes spookily so. More than once I had the feeling I was being watched. Sure enough, just outside my peripheral vision were the low dome, deep sockets, and penetrating stare, like a memento mori, of a solitary seal. Sea lions, on the other hand, have ears and a pronounced sexual dimorphism. Males are crowned with proud sagittal crests and ringed with thickened necks. On land they are agile and quadrupedal; and everywhere they are endearingly vocal. The Steller sea lion is brown and grumbles, whines, growls, and roars, but doesn’t bark. California sea lions are black; their bark is reminiscent of a dog’s.

Pinnipeds can be playful, and therein lies their potential danger. Sea lions are curious and will inspect you en masse with much alarm, surprise, neck craning, discussion, indignity, feints, even play—particularly from the younger visitors—and much general hubbub.

Seals, on the other hand, are more solitary, yet shy and curious at the same time. When I saw an article in Sea Kayaker (April 2002) on seal attacks, I was incredulous and flipped right to it. Kayakers have usually associated a seal’s reservation with their long history of human predation. Perhaps. But maybe that legacy is changing, and seals seem to be adapting. Documented “attacks” on kayakers, divers, and swimmers are confined to bumping and light nipping—no skin breaks: classic signs of play behavior. After all, a seal is a predator and could inflict serious harm if that were its intent. The kayak “attacks” have occurred only around Texada Island (near Mouat Bay) in the Strait of Georgia and near Anacortes, Washington (in Puget Sound), where one seal seems to like to play pirate and board kayaks.