4

VANCOUVER ISLAND

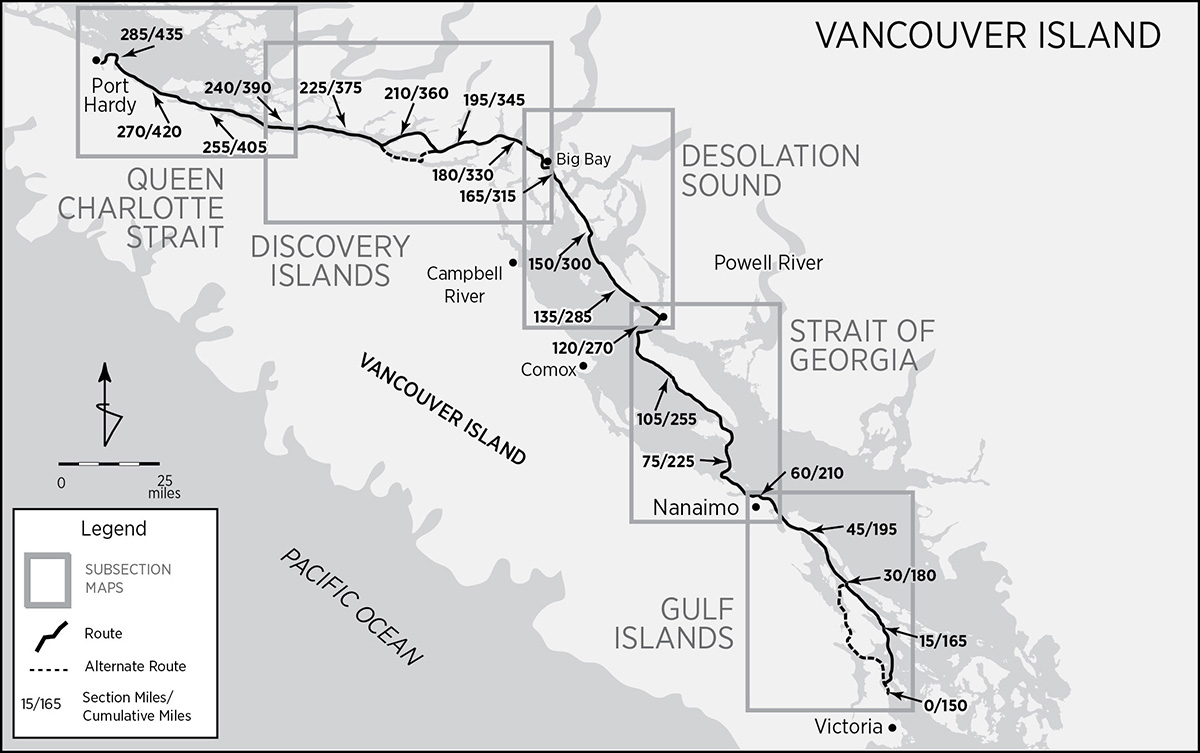

Sidney to Port Hardy 287/437 miles

Sidney to Port Hardy 287/437 miles

We are in the extreme centre,

the radical middle.

That is our position!

—PIERRE TRUDEAU

“Are you bringing in any liquor, beer, wine, or tobacco?” In spite of the businesslike punctiliousness of the question, the Canadian Customs agent’s carside manners were leagues ahead of those of his US counterparts, who give the impression of having trained under sadistic proctologists.

Indeed we were: wine and pipe tobacco, one slightly in excess of the allowed limits. No matter. An honest declaration rendered a generous individual exemption.

“Are you carrying any self-defense devices such as guns, pepper spray, or mace?” This time the eyes narrowed suspiciously, homing through the response to detect revealing body language.

Our shotgun passed muster without a glance, but the US-made pepper spray was apologetically confiscated. Curiously, although pepper spray is legal in Canada for bear protection, it must be labeled “for bears.” Perhaps the label inhibits its use against other predators. We later forked out $80 for two Canadian-made capsicum bear repellents.

Not one question about drugs or suspicion concerning illegal stowaways. Canada’s border priorities are obvious: first, an unfailingly polite welcome, then liquor and tobacco smuggling—vice taxes are not only an important source of revenue, they embody a long tradition of reformist social policy that discourages unhealthy habits—and, finally, handgun prohibition. Canadians are proud of their civil society and deathly afraid of contracting what they perceive as a US epidemic of handgun violence.

By law, you are now required to carry a passport. However, you may be asked to produce only a driver’s license or nothing at all. Remember that admission and duration of stay are at the discretion of the immigration officer at the border.

It is a pleasure to be in Canada. The towns and countryside are spotless and never crowded. Canadians are patient, tolerant, and egalitarian to the core. A leisurely civility and understated formality barely conceal an endearing earnestness—about the most trivial of life’s minor curiosities—that disarms even the most irascible visitor. Finalizing preparations for the second leg of our Inside Passage trip could not have been more pleasant. In sharp contrast to our apprehension at embarking from Boston Harbor, we were impatient to resume our trip and discover what surprises Vancouver Island held along its eastern verge.

The only way to get to Sidney from the mainland with a vehicle and kayaks is via ferry. Ferries depart from Port Angeles; Seattle; Anacortes; Bellingham, Washington; and Tsawwassen, British Columbia. All but two converge on Victoria. The Anacortes and Tsawwassen ferries dock in Sidney.

Tina expressed minor concern over the slight gap in the continuity of our route. Actually, the beginning of the second leg is south of where the first leg ends, and the route north comes within 4 miles of it. Stuart Island’s northern tip lies at latitude 48°, 40 minutes, while Island View Beach Regional Park, the start, is at 48°, 35 minutes. Island View, about halfway between Victoria and Sidney, is an ideal staging point from which to get organized and take off. The park itself is undeveloped except for a parking lot and launch ramp, but adjacent to it is a private campground. The setting is rural, reasonable, and relaxed. Drive north from Victoria on Highway 17 and turn off onto Island View Road. Follow it to the park at the road’s end. One can either engage long-term parking right there or rent a car at the nearby Sidney/Victoria airport for a shuttle to Port Hardy, this leg’s northern terminus. We spent a day getting ready and spent another day shuttling our vehicle with a rented car to Port Hardy. After returning the rental car, we took an airport taxi to complete the 5 miles back to Island View.

An alternate start is located just north of Sidney at McDonald Provincial Park. Although the setting is not quite so rural and the park is not actually on the water (the shore is just across the road), McDonald Park has 39 sites and all the amenities. Just continue north on Highway 17 until you reach the park. A third possibility—particularly if you took the Anacortes to Sidney ferry—is launching just south of the dock alongside Lochside Drive.

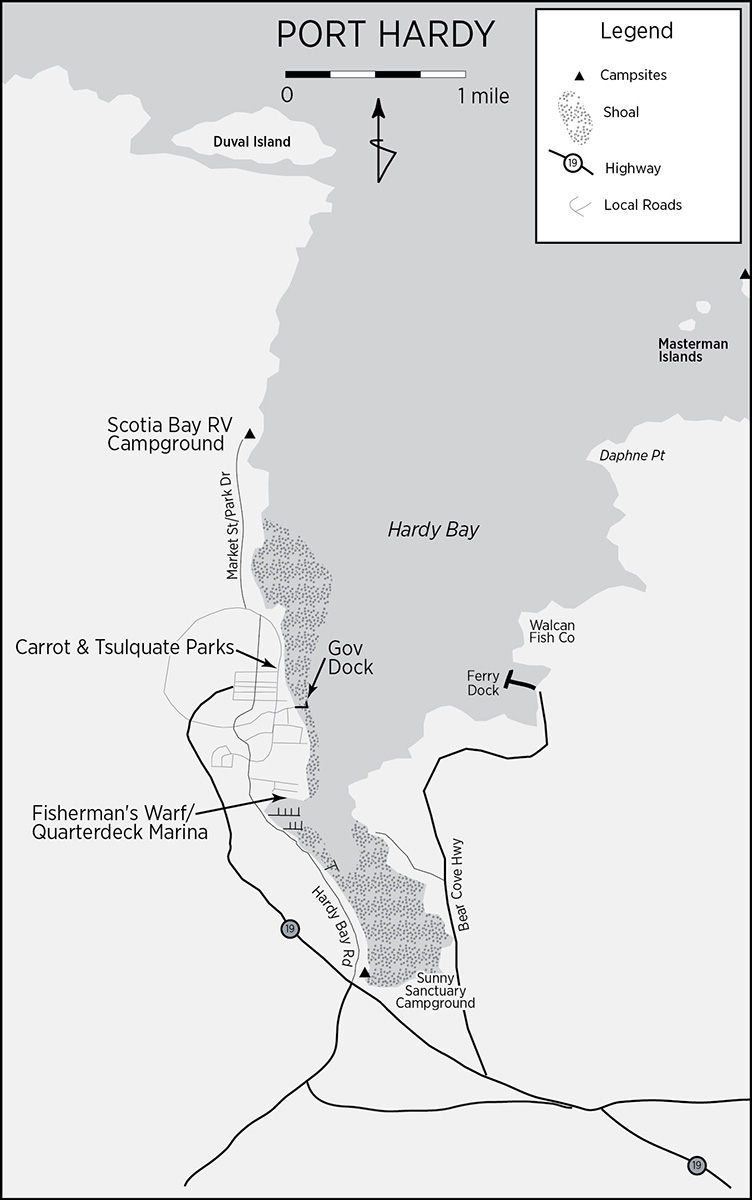

There are at least four options in Port Hardy for long-term vehicle parking. At the bottom of Hardy Bay is the Sunny Sanctuary Campground (250-949-6753) near the south end of town, at 8080 Goodspeed Road, just off the trans-island highway. Although it’s located on the water, you’ll probably not be able to paddle right in at the end of the trip, as the tidal mud flats are extensive and only covered for a short period during high tides. No problem, as the road parallels the bay. Sunny Sanctuary charges about $50 Canadian for vehicle storage. Next up is the town’s public pay parking at the Fisherman’s Wharf, 6600 Hardy Bay Road. This is the lot adjacent to the public docks that most boaters use. It has several advantages, including public restrooms, showers, a launch ramp, and a central location that is easily spotted from several miles away, low in the water. Near the north end of town, just north of the Government Wharf, the public beaches of Carrot and Tsulquate Parks provide an excellent launch and take-out spot. Debbie Erickson, in Kayak Routes of the Pacific Northwest, suggests checking with the Northshore Inn (corner of Market Street and Highway 19), less than a two-minute walk away, for parking. Just out of town and at the north end of Hardy Bay is the Scotia Bay RV Campground. Access is north off Market Street/Park Drive and straight through the Tsulquate Reserve.

Canadian History, Eh?

Canadians believe that their history is short, boring and irrelevant.

—HISTORIAN DESMOND MORTON

Residents south of the border would probably agree. (But then, they also believe that Canadians all want to be Americans.) Such a verdict, if not already based in ignorance, inevitably leads to it. One museum curator in Powell River couldn’t even specify just what Canada Day, July 1, exactly commemorates. Canadian politics are even more enervating, somewhat like watching concrete set, and in slow motion at that. And this is no exaggerated metaphor. The United States can proudly point to July 4, 1776, as Independence Day, an event unambiguous in its explicitness. When did Canada become independent? A nation? Is it independent? Who knows? You decide:

1791: The ink was hardly dry on the Treaty of Paris (the one that confirmed US independence) when Britain, so as to preclude similar events farther north (and not a moment too soon) decided belatedly to remedy the ills that had wrought revolution among the 13 southernmost colonies. In 1791 the British Parliament passed the Constitutional Act extending the rights of the British Constitution, and thus representative government to the remaining North American colonies. Thenceforward, taxation would be with (limited) representation. At the same time they created a separate English Canada (distinct from French Canada), namely Upper Canada, the future Ontario.

1837: The republican virus finally infects Canada. Seeking more representative legislatures, first Lower, and then Upper Canada experience rebellions, with conspirators using US territory for organization. British troops, with the help of the American government, quell the uprisings. But Britain’s Lord Durham’s report on the rebellions leads to reform and union in 1840.

1840: Two of the North American colonies, Lower Canada (the future province of Quebec) and Upper Canada become one under the Act of Union. The remaining colonies, clustered around the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, were known as the Maritime Colonies (see below).

1848: All remaining British North American colonies—Canada, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island—achieve self-government (internally).

When the US-Mexican War broke out, Britain realized that its interior North American colonies were hopelessly indefensible. The US Civil War further underscored that impotence. It didn’t help that Britain actively aided the Confederacy, not only by recognizing it but also by trading with it to the extent of running the North’s naval blockade. Moreover, Canada, as ever, promiscuously welcomed refugees of all stripes, from escaped slaves, Union draft dodgers, and deserters to Confederate combatants, both active and on the run. Britain’s support for the South is usually attributed to its cupidity—the sale of manufactured goods in exchange for cotton (with not a little revenge for the Revolutionary War thrown in). But it was also concerned about the defense of Canada, so it took every opportunity to weaken US power so as to declaw the eagle next door. But idealism also played no small part. Let me explain.

A political and philosophical upheaval, rooted in the Scottish Enlightenment ideals of John Locke, David Hume, and Adam Smith, and the republican principles of the American and French Revolutions, had swept the kingdom in the mid-1800s. It demanded uncompromising liberty for all. The first casualty was slavery. Britain not only abolished it in 1837, it then set out, with its control of the seas, to eradicate the slave trade. It was so successful that it forced the United States to follow suit, at least in outlawing the slave trade. But slavery was only a small part of a larger perspective.

Britain had also come to believe in the political self-determination of all peoples and absolute free trade, not only for its own sake but also as the only way to foster economic development and lift the poor out of poverty. It was these ideals that led not only to support of the South but also to an active effort to divest itself of its colonies. By 1863 Britain was pushing for an independent Canada responsible for its own defense. Looked at another way, the United States had to revolt to free itself of Britain, but it was Britain that had a revolution to rid itself of Canada. (At this point, a cynic might point out that much of the British Empire survived for a very long time. It’s a long story. Suffice it to say that, like Nixon withdrawing from Vietnam “with honor,” Britain sought to free its colonies “responsibly.”)

1867: The British North America Act creates the Dominion of Canada, a union of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Canada (Quebec and Ontario). Prince Edward Island refused to join until 1873; Newfoundland didn’t join until 1949. It was supposed to be the Kingdom of Canada. But ever the politically correct and inoffensive good neighbor, the new entity did not want to offend republican sensibilities south of the border, especially since, at the close of the Civil War, the United States had the largest standing army in the world. Leonard Tilley, premier of New Brunswick and a very devout Christian, turned to his Bible for inspiration. His thumb fell on Psalms 72:8 “He shall have dominion also from sea to sea . . .”

Canada quickly expanded westward. In 1869 Britain facilitated the transfer of Rupert’s Land (named after Prince Rupert, first governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company) to the new dominion for £300,000. This huge expanse, which included much of future Nunavut, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, plus parts of Ontario, Alberta, and the Northwest Territories, had been separately jurisdictioned to the Hudson’s Bay Company. Manitoba was then quickly organized into a province and admitted in 1870. The far west, consisting of the future British Columbia, the remaining portion of the future Northwest Territories, and the Yukon, was claimed by Britain and held under a status separate from that of Canada proper. But not for long. British Columbia, after a short identity crisis during which it considered joining the United States, became a province in 1871. The 1897 Klondike gold rush drew a huge influx of population into the Yukon watershed. But not enough to warrant provincial status—the Yukon Territory was admitted in 1898. The Northwest Territories joined piecemeal in 1870, 1876, and 1895. Alberta and Saskatchewan joined as provinces in 1905. Nunavut became a separate territory in 1999. The dominion was now whole.

1914: British colonies’ response to Britain’s entry into World War I was swift and untemporizing. The dominion was proud to go to the aid of the empire (with the exception of French Canadians, who fiercely resisted conscription). However, the men who came home often found that fighting for Britain had, paradoxically, made them feel more distant from it while at the same time creating a distinctly Canadian consciousness and cohesion. Many historians see WWI as Canada’s “war of independence,” with the 1917 Battle of Vimy Ridge as Canada’s defining moment. Vimy Ridge, a German position held against combined British and French forces, was stormed and captured by four Canadian divisions—at a cost of 10,600 lives—fighting together for the first time. Stephen Harper, prime minister during the 90th anniversary celebrations, described the battle as a “spectacular victory, a stunning breakthrough that helped turn the war in the Allies’ favour.” Additionally, during the war’s final hundred days, Canada’s corps defeated a quarter of Germany’s divisions on the western front.

1919: Following World War I, the victors chartered the League of Nations, forerunner of the United Nations. It was to include all nations and serve as a forum for conflict resolution, particularly since the Great War had not turned out to be the “war to end all wars.” But what was “a nation”? Canada, with Britain’s support, insisted on being seated. After all, Canada, under Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden’s demand, had put its own signature on the Treaty of Versailles rather than have Britain sign on its behalf, as was previously done. The United States was furious and saw it as a ploy to use mere colonies to give Britain extra votes. Though President Woodrow Wilson reluctantly withdrew his objections, the US Congress demurred and petulantly refused to join.

1923: Canada was still a British colony. Foreign affairs were conducted through the British Foreign Office. In anticipation of handling its own foreign affairs, Canada had created the Department of External Affairs in 1909. In 1923 Canada concluded (without the British Foreign Office’s imprimatur) its first independent treaty—the Halibut Treaty—with a foreign power, the United States. This was soon followed, in 1927, by the opening of a legation—not a full-fledged embassy, mind you—in Washington, DC.

1931: The Statute of Westminster establishes the legislative autonomy of Canada and becomes the basis for the British Commonwealth of Nations by the “autonomous nations (Canada included) of an Imperial commonwealth” with control over their own internal affairs and “an adequate vote in foreign policy and foreign relations.” The British Privy Council, however, remains the final court of appeal.

1947: The Citizenship Act redefines citizens as, primarily, Canadians. Heretofore they had been, first and foremost, British citizens.

1949: The Supreme Court of Canada becomes the final court of appeal, replacing the British Privy Council.

1965: Under pressure from an ever-restless Quebec, the Canadian flag—with its imperial banner of the crosses of St. Andrew and St. George—becomes the red and white maple leaf.

1982: Queen Elizabeth II signs the Constitution Act, severing Canada’s anomalous dependence on the British Parliament and formally entrenching the monarchy’s position.

2018: The Canadian head of government is the prime minister in a parliamentary system; the head of state remains Queen Elizabeth II (the one who lives in Buckingham Palace, London). On the beat, she is represented by her viceroy, Canada’s governor general.

The US-Canada border has been described as the longest undefended frontier in the world. It wasn’t always so. For nearly a century, Canadians feared a US invasion. At the start of the US War for Independence, which colonies would join the revolt and which would remain loyal was an open question. French Canada, ironically, had no doubts—they had no quarrel with the king. For one, they perceived the dispute as a ruction between the English speakers. More importantly, the Quebec Act of 1774 had just guaranteed the French many rights they had been clamoring for. This did not sit well south of the St. Lawrence, especially since the act also gave the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes to Quebec.

For 10 years a growing estrangement between Americans and the king, caused by British attempts to assert greater control over colonial affairs, had been poisoning relations. For the crown to suddenly address French grievances while ignoring those of the English speakers was as much a casus belli as the tea tax (imposed, by the way, to help recoup revenue deficits due to Britain’s recent conquest of New France). The very first act of the American Continental Congress, when it first convened in 1775, was not to declare independence but to invade Canada. Generals Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold marched on Montreal and Quebec, respectively. The invasion polarized the indecisive. Loyalists poured across the border. English Canada and the Maritime Colonies joined loyal Quebec. Though Montreal was captured, the Americans were routed at Quebec. On July 2, 1776, two days before the Declaration of Independence was signed, the soon-to-be United States withdrew from Canada.

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 did not really settle anything; it was more a cease-fire than a resolution. Neither side adhered to its commitments. No one expected it to be the last word on the American revolt; after all, there was absolutely no precedent, anywhere, for such a precipitous divorce. John Graves Simcoe, governor of Upper Canada (a.k.a. English Canada, later Ontario) certainly was skeptical. Convinced that Americans would soon repent, he greased the skids by offering free land to anyone renouncing the Revolution and swearing allegiance to the Crown. “Late Loyalists,” many torn between free land and independence, poured into Canada.

The Treaty of Paris transferred the Ohio Valley from Quebec to the United States. However, its ill-defined borders and US settlers’ infringement on aboriginal rights that the English had implicitly guaranteed at the treaty were still a source of friction. Border skirmishes and territorial disputes, erupting into outright battles—with Indian surrogates bearing much of the brunt—flared up in 1790 and disrupted the peace in the Old Northwest territories of Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana through 1795. Meanwhile, presaging the country’s future role as cultural trendsetter, the US’s revolution was spreading like a virus. France caught it in 1789; Haiti in 1804. Soon it spread to all of Latin America. Britain felt cornered and besieged. The result was war with France.

The War of 1812 was inevitable. Britain’s unceremonious boarding and confiscation of US commercial vessels bound for France (added to the still smoldering embers of the northwest frontier dispute) sparked the conflagration. The United States reignited hostilities and upped the ante. Henry Clay, speaker of the US House of Representatives, boasted “that the militia of Kentucky are alone competent to place Montreal and Upper Canada at (our) feet.” President James Madison concurred: “There would be a second War of Independence.” The US Congress authorized the raising of 100,000 troops and invaded Canada to drive out the British.

The war was a draw. Though Britain quickly and decisively reestablished rule of the seas, rebuffed northward incursions, and even managed to burn and sack the new capital at Washington, it made no territorial gains. Much to the chagrin of Canadians, she was more anxious to concentrate on European concerns. The Treaty of Ghent reaffirmed the status quo antebellum: no changed boundaries, no reparations, and no wrongs avenged. Ironically, according to Canadian historian Desmond Morton: “By insisting on war, the American warhawks helped cancel a process that would probably have led to peaceful absorption of the colony (Canada) into the United States.” American isolationist doves, on the other hand, nearly succeeded in rejoining a chunk of New England back to Britain.

US designs on Canada remained very much alive. With Manifest Destiny morphing into actual territorial seizure, Canada remained vulnerable and vigilant. The Aroostook Wars of 1840 contested territory along the Maine frontier. That dispute was finally resolved with the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842. By 1844, presidential candidate James K. Polk was advocating the annexation of British Columbia and adjacent territory all the way up to Alaska. The Mexican War saved Canada. The United States, unwilling to fight a two-front war, agreed to the 49th parallel border in 1846. In 1855 the San Juan Islands Pig War kept confrontation alive.

The last bellicose incident between the two neighbors occurred just after the Civil War. The Irish potato famine of 1846–51 had driven many emigrants to the New World. Those who landed in the United States were soon enlisted in the Mexican War and then conscripted during the Civil War into the Union army. Victory after victory instilled confidence. Conspiring with Irish immigrants in Canada, they hatched a bold but harebrained plot. By enlisting hardened veterans with ready access to arms and American sympathy, the Fenian Brotherhood (precursor to today’s Irish Republican Army) planned to form an army to conquer Canada and hold her hostage for Ireland’s freedom. In April of 1866, Fenians invaded New Brunswick. The next month, 1,600 Fenians defeated two forces of Canadian militia near Fort Erie. US authorities intervened. They apprehended 1,800 Fenians in Vermont before they could act. By June 3 the invasion was over and done. The era of armed confrontation was over.

The next 74 years were not particularly warm. As late as 1911 you could still hear the following in the halls of Congress, by none other than Champ Clark, speaker of the US House of Representatives: “We are preparing to annex Canada, and the day is not far off when the American flag will float over every square foot of the British North American possessions—clear to the North Pole.” Both countries tried to out-tariff the other and, contemptuous of its northern neighbor’s ambiguous sovereignty status, the United States either ignored or thumbed its nose at Canada. Adolf Hitler changed all that. When he invaded Poland in September 1939, Canada dutifully declared war. By June of 1940, with continental Europe overrun by the combined might of Germany and the Soviet Union, Canada was the second most powerful (after England) of Germany’s adversaries. The United States took notice. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King signed an agreement at Ogdensburg, New York, for the joint defense of North America.

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the United States finally “invaded” Canada. A force of 33,000 men marched north for the construction of the Al-Can Highway. The road, built straight through in the phenomenally short time of nine months and six days for the defense of Alaska, is now the closest road access to the Inside Passage.

After the war, Soviet expansionism strengthened and broadened US-Canadian North American defense commitments. Canada joined NATO in 1949 and the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) in 1958. In return, the United States finally recognized Canada’s historic claim to its arctic islands.

Instead of scuttling the mutual defense arrangements at the close of the Cold War, both decided to enter into an even more intimate relationship, including Mexico this time, with the launching of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1993. Vicente Fox, Mexico’s president from 2000 to 2006, even floated the idea of sharing a common currency.

The salmon (and lumber) wars, however, still disrupt the honeymoon. Mark MacGuigan, one-time minister of external affairs, has declared that “the most serious dispute we have with any country is with the United States over fish.” Canada accuses US fishermen of harvesting a disproportionate share of salmon returning to their spawning grounds, thereby both reducing Canada’s take and depleting overall stocks. Confrontations have escalated to the point that, for a short time, Alaska ferries were refused docking privileges at Prince Rupert, BC. The salmon wars are not over yet, but interim treaties have defused the antagonism, and ferry service has resumed.

The lumber wars center on the US accusation that Canada sells its lumber below the border at below-market prices. When the accusation was referred to the NAFTA arbitration panel, they ruled that the United States must drop import duties and return those it had already collected. The Bush administration ignored the ruling. “Unacceptable,” thundered Canada’s prime minister.

If truth be told, Canadian history, boring or not, is enviable in at least one respect: Canada managed to avoid most of the wars the United States fought. To some degree this is due to the different temperaments of the two populations. At the time of the Revolutionary War, complacent conservatives (Tories) gravitated north, while dissatisfied radicals (Whigs) sorted themselves south. While the American Declaration of Independence celebrates “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” Canada’s founding document promises “peace, order and good government.”

Reluctance to join the War for Independence was well founded. At that time, revolutions had no track record. The US Articles of Confederation turned out to be a failure marred by instability and conflict, such as the Whiskey Rebellion. The subsequent French, Haitian, and Latin American revolutions were all disastrous. The Mexican and Spanish-American Wars, or anything analogous, never tempted Canada. Canada had no Indian Wars. Indian relations, barring a few minor conflicts, were pursued much differently. The Vietnam War was roundly condemned, both popularly and officially, much to the displeasure of President Lyndon Johnson, who summoned Prime Minister Lester Pearson and dressed him down: “Lester,” he told the Canadian, “you peed on my carpet.”

The Canadian art of war avoidance reached new pinnacles of creativity in its dodging of anything resembling our Civil War. Quebec separatism has always threatened to dissolve the union, but Canadians would never, like their more bellicose neighbors to the south, go to war over it. The Canadian Supreme Court has even spelled out the proper procedure for secession, unthinkable in the United States. A typically Canadian row erupted in 2005 with the opening of the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. Many felt that war ought in no way to be memorialized. Instead, Canada’s many international peace-keeping missions and war-averting diplomatic achievements should have been given priority.

Perhaps what makes Canadian politics so frustrating, unintelligible, and yes, even boring to Americans is the more than usual lack of congruence between political parties and any sort of principled political philosophy. Consistency has been sacrificed to national unity, growth, and development that, in such a geographically sprawling and climatically extreme country, all parties promote through vigorous federal intervention and subsidies. Each election seems to be contested by politicians with a big wish list of concrete promises that expediency and the demands of a fractious confederation often reverse 180° within days of victory.

The inviolability of the dominion, or Canadian unity, has always been a vexing problem. That word, “dominion,” doesn’t help—and lately “confederation” has been favored. Most countries are republics, kingdoms, or some such neatly identifiable entities. Canada is the only dominion in the world. In an effort to more clearly define Canadian cohesiveness, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau initiated a process to develop a new constitution for the confederation. The latest proposal, the Charlottetown Accord, and its predecessor, the Meech Lake Accord, both failed at the last second.

The main problem was Quebec. It had never experienced parity with the other provinces and rejects it, on principle. In spite of many efforts to relegate it to the status of just simply another province, Quebec demands special status: co-equal with all the other provinces en masse, as a culturally different founding nexus, with its own language and traditions, and greater power in the federation. When the Meech Lake delegates swallowed their sense of fair play and conceded Quebec’s demands, the First Nations piped up and decided they too wanted a special status within the newly proposed constituency.

The First Nations, precontact inhabitants who had never been subjugated by war but had instead been co-opted by treaties, decided to reassert their prerogatives. They came in four competing groups: “status” and “nonstatus” Indians (those who lived on and off reserves), Metis (French-Indian hybrids), and Inuit. The First Nations reasoned that if Quebec’s claims preceded the other provinces, their claims certainly preceded all others. The ensuing fudges, half-measures, and compromises ended up being unacceptable to all parties. The new, improved constitution did not pass.

If you think this is a lot more Canadian history than you bargained for, consider that not only is half the entire length of the Inside Passage in Canada but, conversely, the Inside Passage encompasses Canada’s entire Pacific Coast. And, after all—in spite of all the muddles—Canada, according to the UN, has consistently ranked as one of the best countries in the world in which to live and, according to US News and World Report, was ranked #2 in 2018, behind Switzerland.

VANCOUVER ISLAND

Spain based her exaggerated claim to all circum-Pacific lands on Balboa’s “discovery” of the Pacific Ocean. When she got wind that Russia was not only exploring but also settling territory in the Pacific Northwest, she sent an expedition under Juan Perez to strengthen her claims and counter Russian expansion. By 1774 Perez had reached the Queen Charlottes and traded with the Haida.

Into this finely balanced though straggly détente, Britain thrust its curious nose with an innocent expedition commissioned to search for a northwest passage connecting the Pacific with the Atlantic above or through North America. History credits James Cook with discovery of Vancouver Island, though it is likely that others—perhaps Sir Francis Drake; more likely Japanese fishermen—preceded him. In 1778 he anchored at Nootka, cut wood, brewed spruce beer, repaired his vessels, and set up an astronomical observatory. Even while his ships were searching for anchorage, canoes began approaching, seemingly without fear or distrust of the strange vessels. Subsequent visits by Americans, Russians, French, more English, one or two nominally Portuguese and Austrian ships, and even small Spanish and English settlements invested a global importance on the small village. Spain was not happy.

By 1788 Spain had decided to expel all foreign interlopers and trespassers from the Northwest Coast. Ensign Esteban Jose Martinez single-handedly set out to enforce the empire’s integrity. A spark looking for a fire to ignite, he was possessed of a hair-trigger temper (particularly while drinking), a foppishly pompous self-importance, and was given to big talk and braggadocio. He was the chip on the shoulder of Spain’s empire. At Unalaska, in the Aleutians, under the very noses of his Russian hosts, he had the audacity to take formal possession of Alaska.

At Nootka, he seized three British ships intent on establishing a trading settlement and arrested their captains and crew. It didn’t help when one of the skippers, Captain Colnett, roundly insulted him. Britain prepared for war. Prussia and Holland, under the terms of the Triple Alliance, backed her. Spain appealed to France, but King Louis XVI, about to take a short walk to the guillotine, was indisposed. Spain had no choice but to capitulate. The Nootka Conventions of 1790, 1793, and 1794 were the beginning of the collapse of the Spanish colonial system. Spain retreated south to California while Britain promised not to settle Vancouver Island in the immediate future, leaving Nootka a nominally free port.

Before the founding of Victoria in 1843, Nootka Sound—slightly more than halfway up Vancouver Island’s west coast—was unquestionably Canada’s western capital. Explorers, traders, and diplomats gravitated to its well-positioned harbor and hospitable inhabitants. Maquinna, chief of the Nootka, rose to the occasion.

An imposing, sophisticated, and intelligent man whose long administration lent stability and continuity to the tentative but inevitable new contacts, he rolled with the punches wisely and admirably. By 1792, he more than likely spoke a good deal of Spanish. According to Juan Francisco Bodega y Quadra, his table manners were near perfect and he was well aware of the political and acculturational situation in which he and his people were involved. But he was no doormat. When treated treacherously, he would counterattack, with success. He even held white slaves that he treated equitably, not only according to his customs but also with some consideration for their European sensibilities.

One of the last important Spanish expeditions, co-led by Dionisio Galiano and Cayetano Valdes in the Sutil and Mexicana, circumnavigated Vancouver in 1792, proving once and for all that it was in fact an island. Their charts of Desolation Sound actually show more detail than Vancouver’s charts. Both expeditions probably unofficially collaborated as they worked their way up the east side of the island. In the diplomatic spirit of the ongoing Nootka deliberations, the island was christened “Quadra’s and Vancouver’s Island.”

In the intervening years the Hudson’s Bay Company had concentrated development of its westernmost district in the Oregon Territory, with the capital at Fort Vancouver, just north of the Columbia River. US expansionist pressures in the 1840s and the anticipation that Puget Sound might soon be ceded to the Americans caused HBC Governor George Simpson to look for new headquarters farther north. The recently surveyed harbors of Sooke, Victoria, and Esquimalt on the southeast coast of Vancouver Island were perfectly positioned as a strategic bulwark against further US encroachment. Fort Victoria was erected at the head of Victoria Harbour in March of 1843; the Songhee, a band of the Coast Salish inhabiting the area, were very pleased.

Victoria prospered. It was at the hub of a trading network that sent manufactured goods from England and the United States to Hawaii, Russian America, and Canada in return for raw materials. Victoria took a cut. In 1849 Britain made Vancouver Island a Crown Colony and put the Hudson’s Bay Company in charge. Governor Simpson transferred HBC headquarters from Fort Vancouver to Victoria. In 1856, the HBC turned over administration to a locally elected legislative assembly and governor, James Douglas. Douglas, who also governed British Columbia as HBC factor, retired from both positions in 1864. The resulting separate dual governorships, heretofore held by one man, proved ungainly. The two Crown Colonies (BC had become one in 1858 and officially christened “British Columbia”) merged in 1866 with the united capital at Victoria.

NATURAL HISTORY

Vancouver Island is 279 miles long and 75 miles at its widest. The south and east coasts, where the majority of the population is concentrated, are mostly level while the interior consists of a rugged mountain chain exceeding 7,000 feet in altitude. Deep coves and bays indent the west coast, with Quatsino Sound nearly bifurcating the island near the north end. Vancouver indulged his sense of symmetry—and vanity—by nestling his namesake island between two bodies of water commemorating his sovereigns: the Strait of Georgia (I suppose the Strait of George might have sounded a bit prosaic) and Queen Charlotte Strait (Charlotte was wife to George III). Discovery Passage and Johnstone Strait separate Vancouver Island from the mainland by a scant 1.5 miles at the narrowest point.

Vancouver Island mountain ranges block and squeeze Pacific weather fronts, creating a relatively dry and sunny rain shadow along the Strait of Georgia. You can expect relatively clear skies about 60 percent of the time, with about five days per month of measurable precipitation during the paddling season. North of the city of Vancouver the mainland shore is known as the Sunshine Coast, while the Gulf Islands have been nicknamed Canada’s Hawaii. Annual rainfall in the Gulf Islands rarely exceeds 32 inches, with only 25 percent of that falling between April and October. Galiano Island, the driest, gets less than 23 inches.

July and August are the warmest months with the average daily temperature range between the low 50s and low 70s F. During warm spells, 85°F temperatures are not uncommon, and highs of 95°F have been recorded, though due to the cooling effect of sea breezes, maximum air temperatures on the water seldom exceed 73°F. These same sea breezes are common during hot weather and are caused by differential heating between land and sea. They peak in the afternoon, sometimes causing uncomfortable chop for the kayaker. The predominantly clear weather generates gentle northwest breezes, when conditions permit, which is about half the time. Huge amounts of fresh water invade the straits and channels between Vancouver Island and the mainland during summer runoff, actually lowering the mean summer sea temperature of 58°F by about 5°F.

Tides behind Vancouver Island flood and ebb from both ends. The exact spot where they meet is near Stuart Island. North of Stuart, sea temperatures are a good 10° cooler. Air temperature drops commensurately—you’ll not see madrona trees anymore—and tides exhibit a marked diurnal inequality: for instance, one day’s two low tides (or high tides) will be substantially different. In the Gulf Islands during the summer, the lower low tide generally occurs in the morning, while the higher high tide sweeps in at night.

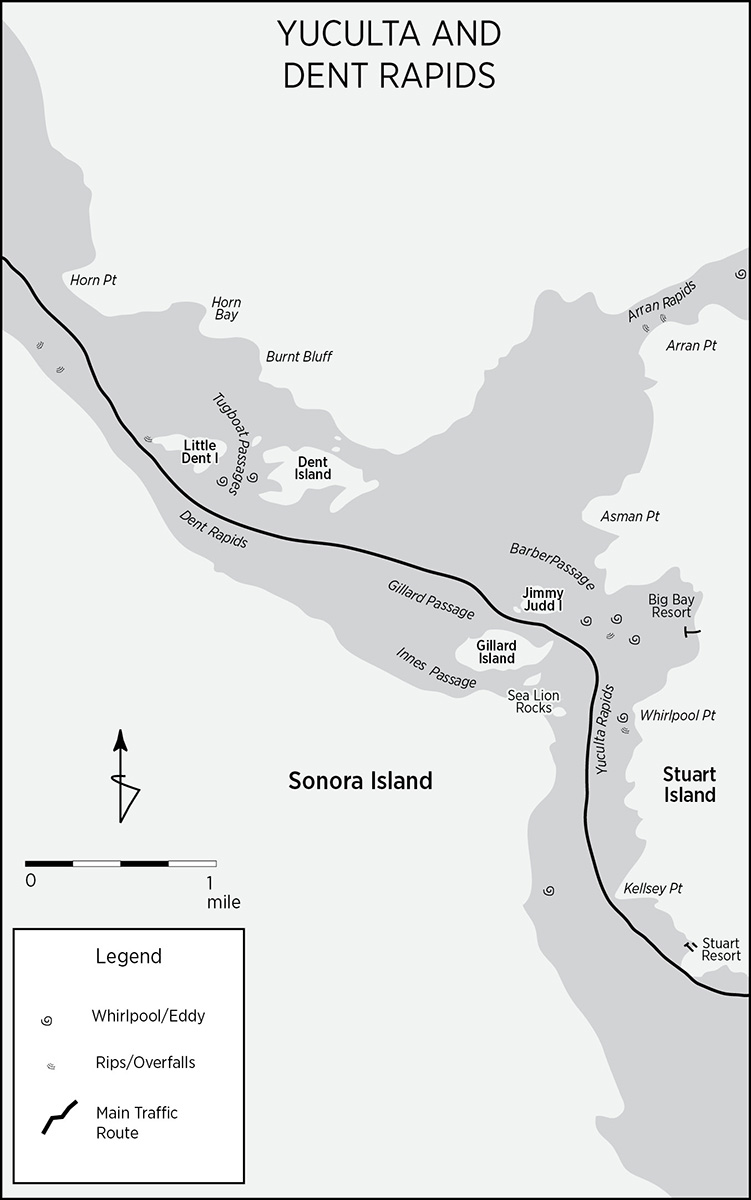

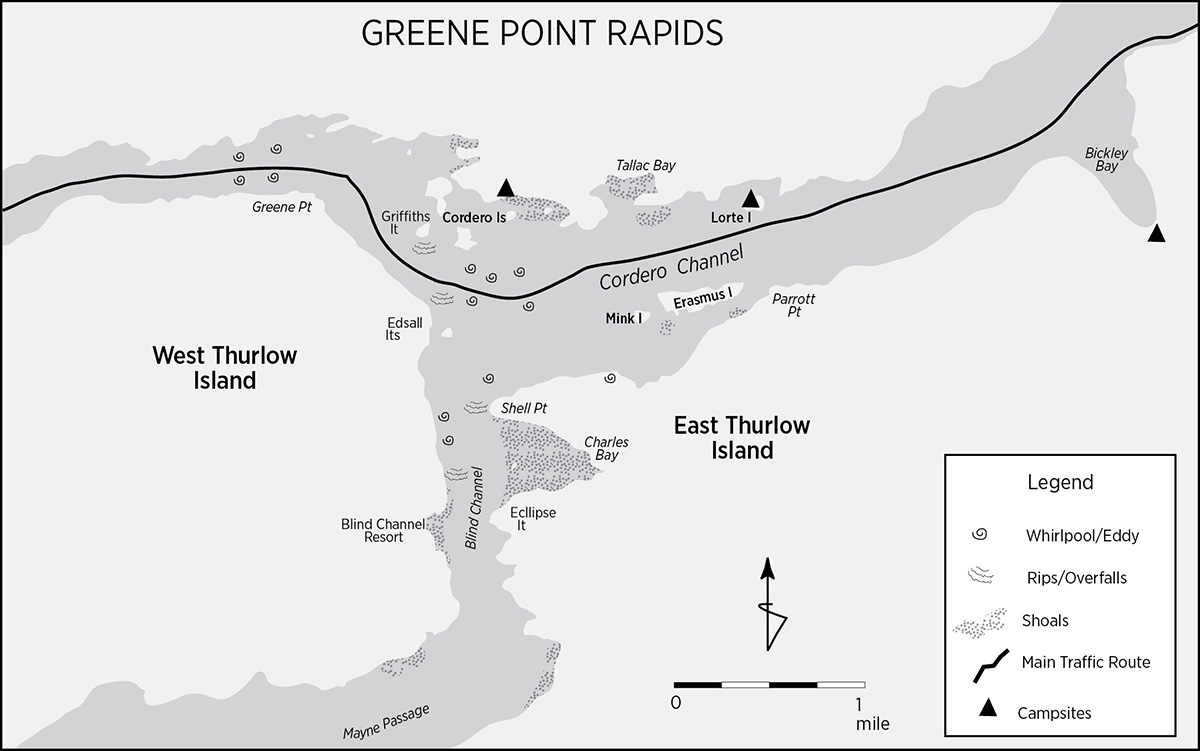

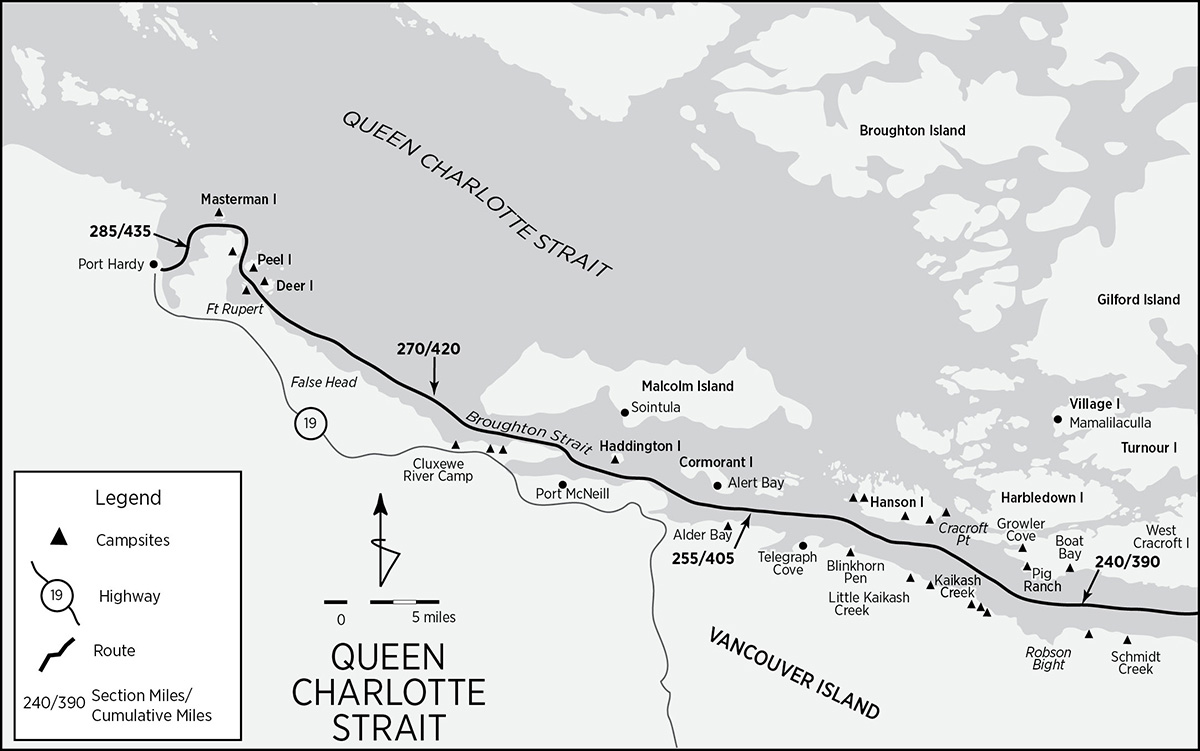

The tremendous distance tides must travel behind Vancouver Island and the extreme constriction wrought by the archipelago separating the two land masses creates tidal currents in excess of 15 knots through Seymour Narrows. Currents follow the mostly southeast-northwest trend through the multitude of alternate passages and, though not as strong as in Seymour Narrows, still warrant due diligence. Saltwater rapids form and impede a kayak’s progress in all of the channels that course north of the Strait of Georgia. All have to be negotiated at slack, with impeccable timing. Boats of all types and sizes will converge at narrow passes at this time. Most currents in the Gulf Islands seldom exceed 2 knots, except through some of the narrow passes between islands, such as Dodd Narrows and Gabriola Pass, where they can reach 9 knots. Very generally, if you want to coordinate your paddling with the tides, they ebb south in the morning and flood north in the afternoon. Queen Charlotte Sound and Johnstone Strait pose no extraordinary hazards other than a paucity of campsites—mostly due to steep, highly vegetated ground cover—beyond Desolation Sound until the vicinity of Telegraph Cove.

South of Lund, population density and private property limit camping opportunities. In the Gulf Islands, most of the shoreline above the historical high-tide line is private property. However, in Canada there is no such thing as a private beach. In theory, all foreshore between high and low water is Crown land and legally accessible to the public. Still, no one wants to camp in front of a residence and possibly shift his tent during the wee hours of the night to avoid a high-tide soaking.

In light of this, the British Columbia Marine Trail Association (BCMTA) was organized in the early 1990s in tandem with the Washington Water Trails Association to pursue the vision of the Cascadia Marine Trail (CMT) all along the BC coast to Alaska. Plans are to designate campsites about every 10 miles. Some sites are already established in the form of existing marine parks. Other sites have been licensed to the BCMTA by private landowners. Contact or join the British Columbia Marine Trails Network (BCMTN), the successor to the BCMTA, by logging on to their website, www.bcmarinetrails.org. Their detailed Google Earth maps pinpoint known campsites, with new campsites added as they are identified.

Another useful resource for the British Columbia coast is the West Coast Paddler, a webpage—constantly updated—with trip reports and campsites.

The Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy, a five-year program designed to expand an integrated network of Pacific Coast Marine Parks, was launched in 1995, dovetailing with the BCMTA/BCMTN objectives. The goal, involving both federal and provincial governments, was the acquisition of new lands that collectively would comprise a new national park system within the Gulf Islands. That goal was achieved on May 9, 2003, with the establishment of Gulf Islands National Park. Paddlers are welcome on newly acquired lands regardless of their state of development. Besides coastal marine parks, there are several islets designated as public recreation reserves and one piece of Crown land (other than beaches) accessible to paddlers for camping: Blackberry Point on Valdes Island.

Ecological reserves in BC have different restrictions than their counterparts south of the border. Whereas casual, nonconsumptive, nonmotorized use is permitted on most reserves in the province, these areas are particularly delicate—some are pelagic bird rookeries—and are not intended for public recreational use. Landing, though not strictly prohibited, is discouraged.

A variety of policies govern public use of native reserve lands. The Lyackson Band in Ladysmith administers the Valdes Island reserves. Call the band office at 250-246-5019 for permission to camp. The Penelakut Band on Kuper Island administers Tent Island, once a provincial marine park. Call 250-246-2321 or write the Penelakut Band, Box 360, Chemainus, BC, V0R 1K0, for permission to camp on Tent Island. Native reserves, coastal marine parks, and ecological reserves are well marked on federal and provincial topo maps. Nautical charts frequently fail to designate them.

North of road’s end, most of the lands along the BC coast are Crown lands, deeded to the province by the federal government at the time of Canada’s confederation. Management is the responsibility of the BC Forest Service within the province’s Ministry of Forests. Pacific Rim National Park, on Vancouver Island’s west coast, is the federal government’s only land management responsibility.

The Route: Overview

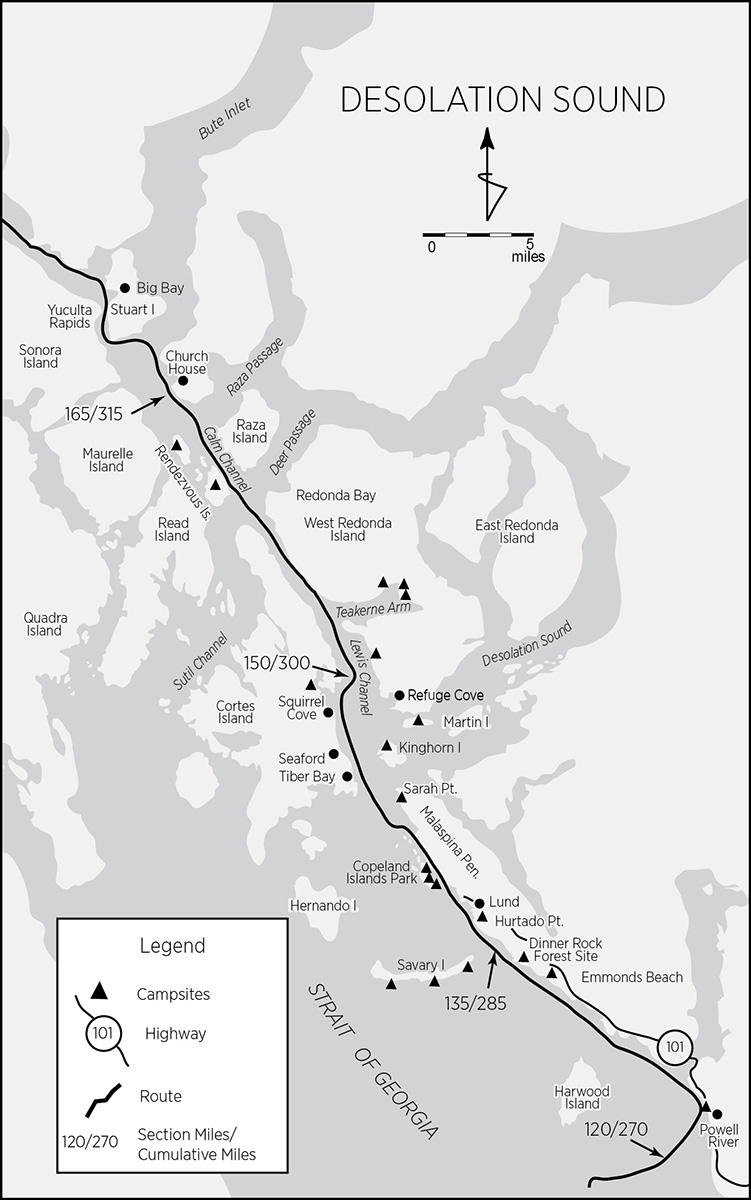

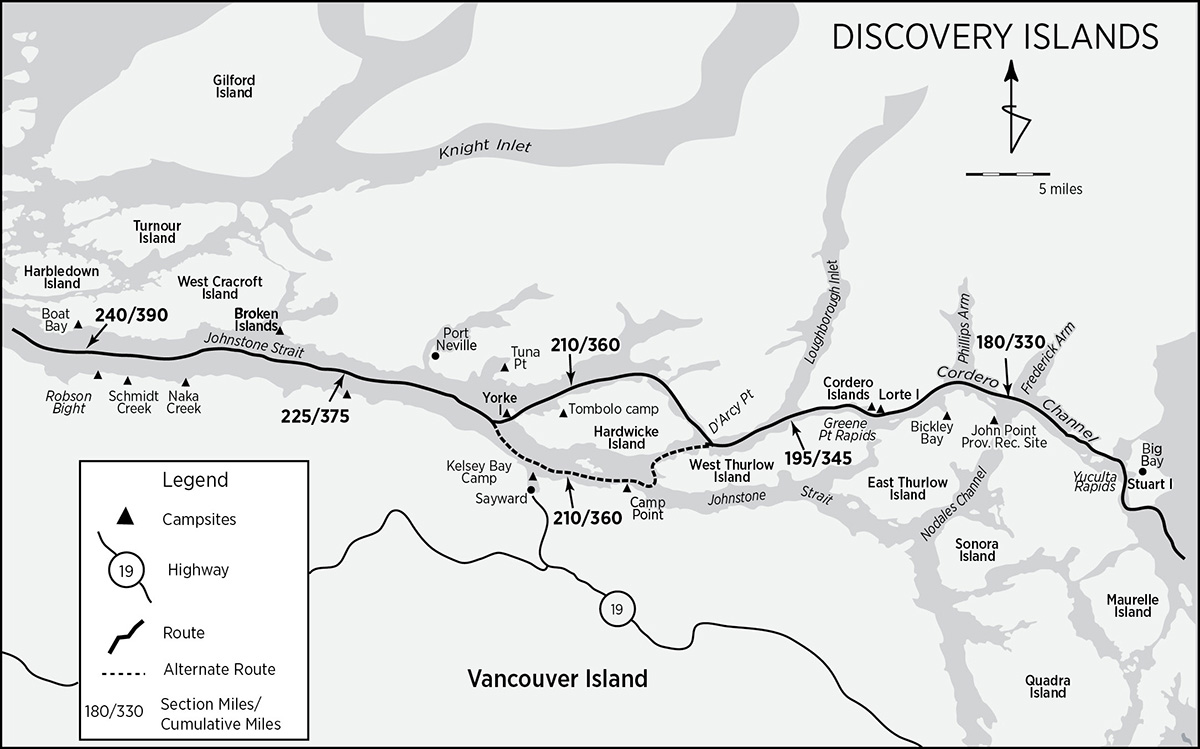

The Vancouver Island section of the Inside Passage is divided into five portions: the Gulf Islands, the Strait of Georgia, Desolation Sound, the Discovery Islands, and Queen Charlotte Strait. Three of the sub-sections have alternate routes.

Starting out from Island View Beach Park, you are immediately confronted with two very attractive route choices: launch headfirst into the beckoning Gulf Islands, with their promise of solitude, or head straight up the more protected Vancouver Island coast. The main route plunges out into the archipelago. Who can resist this cluster of spilled pearls? After the hassles of access and shuttle driving, border crossings, and the hubbub of cities, our first inclination was to get away. The alternate route winds through Sansum Narrows with camping opportunities on Saltspring Island, not an inelegant variation. Both reunite about 33 miles out—neither is longer than the other—off the northern tip of Saltspring Island and follow the Northumberland Channel funnel to Nanaimo. The alternate route is described immediately following their point of reunion.

The route then coasts north of Nanaimo for a short stretch until a suitable crossing is reached for the Ballenas Islands. A glance at the chart would logically suggest the route continue along the coast up into Discovery Passage or Sutil Channel. Instead, our objective is Lewis Channel. Seymour Narrows constricts Discovery Passage where tidal and shipping bulk converge, creating 16-knot currents and congestion. A local sailor suggested Lewis Channel as a safer and more aesthetic alternative. And so it is. From Ballenas, the route hits Lasqueti Island and courses up the west coast of Texada Island, to a final crossing for Powell River.

A scant 15 miles north of Powell River lies Lund, the end of the road and the beginning of Desolation Sound. Snow-clad mountains interspersed with deep fjords constrict any attempt to extend the coastal highway. Sweet desolation indeed! Isolated fishing and logging camps, with associated clear-cuts, are the only obvious signs of man’s touch. The coastal verges are niggardly with campsites, and chilly mists descend from the heavens in an attempt to preclude further encroachment.

Many channels crisscross the Desolation Sound archipelago. All constrict tidal flows to such an extent that saltwater rapids guard all routes north, though none as dauntingly as Seymour Narrows. Our route up Lewis Channel and, in due course, through Calm, Cordero, Chancellor, Wellbore, and Sunderland channels is only one of many possibilities. All lead inexorably into Johnstone Strait, where the route again follows the Vancouver Island coast. Only one minor alternate route is described: around the south side of Hardwicke Island, also described after its point of convergence with the main route.

At Telegraph Cove, the Vancouver Island highway reconnects with the shore, though not obtrusively. Here again, the seemingly logical route and our route diverge. A glance at the map would dictate heading north into the Broughton Archipelago to follow the mainland coast north.

This would be the route of choice for the through-paddler, as the archipelago is stunning and no crossing of Queen Charlotte Sound is required.

This leg, however, ends at Port Hardy, another 30 miles along the Vancouver Island coast. At the edge of a vast wilderness and before the longest piece of unprotected coast along the Inside Passage, Port Hardy is the perfect spot for a pause. Logistically, it is also the ideal terminus for this section, as all services are available and it sits at road’s end with ferry service extending north.

Two additional resources that bear at least a cursory glance before tackling this section are Doug Alderson’s Sea Kayak Around Vancouver Island, Rocky Mountain Books, 2004, especially for coverage of the route I recommend; and Dennis Dwyer’s Alone in the Passage: An Explorers Guide to Sea Kayaking the Inside Passage. Dwyer describes his route up Seymour Narrows and Campbell River with appurtenant campsites—in case you choose to take this other route.

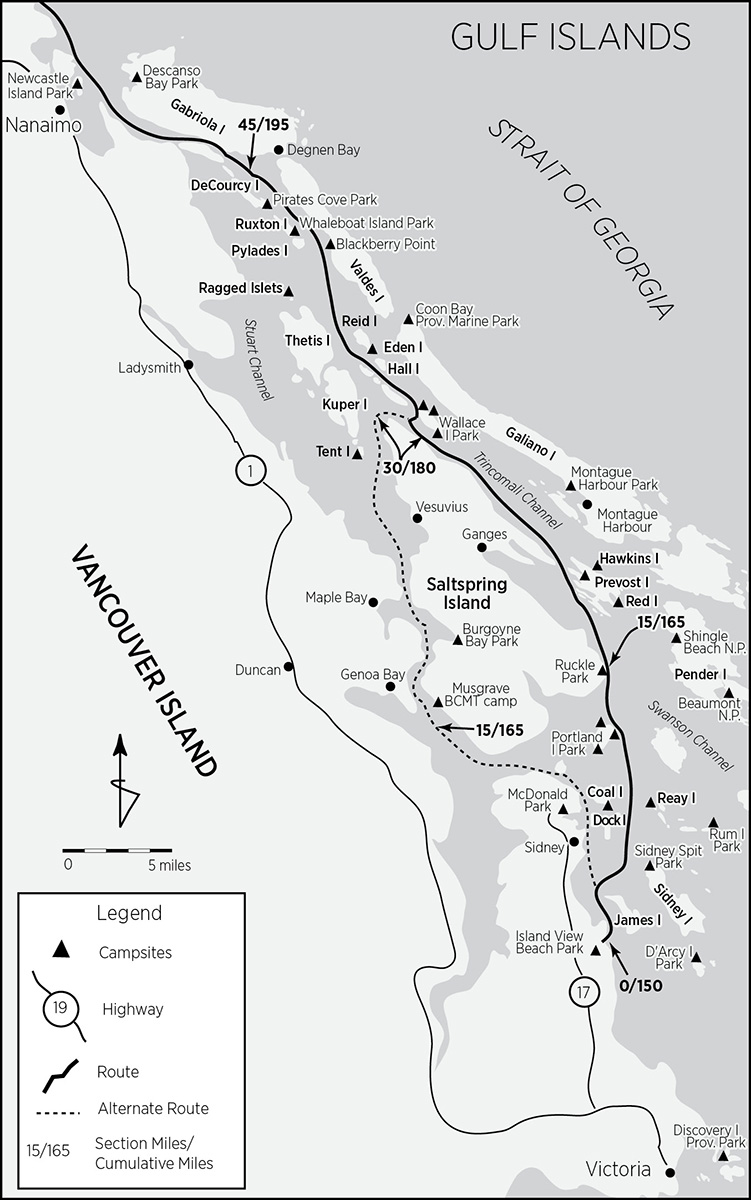

Gulf Islands: Island View Beach Park (mile 0/150) to Newcastle Island Provincial Park (mile 54/204)

Gulf Islands: Island View Beach Park (mile 0/150) to Newcastle Island Provincial Park (mile 54/204)

The Gulf Islands are a historical misnomer. Vancouver, at first believing the Strait of Georgia to be an inland sea, named it the Gulf of Georgia after King George III. Hence, the Gulf Islands. When the “gulf” was discovered to be a strait, the islands’ name remained unchanged. The “Strait Islands” just wouldn’t have the same ring. Many of the islands’ and passages’ names commemorate the naval vessels stationed there during the tensions of the 1850s—HMS Thetis, Portland, Trincomalee, Ganges, and Prevost.

Carved out of sandstone, often eroded into overhangs resembling petrified, breaking waves (which mostly preclude impulse landings), and dotted with huecos and calcified nodules along their brims, the islands have a distinct personality. Rustic old farms and funky artistic communities lend continuity with the San Juan Islands. Numerous shell middens and petroglyphs attest to the thousands of years the islands have been inhabited. There is still an abundance of natural life, with an estimated 3,000 species of plants and animals, including hundreds of seaweed and fish varieties; invertebrates such as octopus, starfish, oysters, clams, green anemones, and spiny red urchins; and large marine mammals including orcas, porpoises, pinipeds, and otters. Bald eagles rule, though there are more than a hundred species of birds, among which are a wide array of ducks, great blue herons, ospreys, gulls, and cormorants.

The majority of the islands are private property, though with good planning an extensive marine provincial park system affords plenty of camping. All marine parks in the Gulf Islands have camping fees (usually about $5 per person per night, though some charge $14–17 per group per night). It helps to carry small bills, $1 (loonie) and $2 (toonie) coins (change is not available), and a pen (usually missing) for self-registration.

Summer weather brings calm morning conditions, usually followed in late afternoon by brisk westerlies that whip up an uncomfortable chop. Plan for early crossings and carry plenty of water, as days can be hot and water sources are scarce. Fires are not allowed.

Standing on the beach at Island View Beach Park prior to launch, contemplating conditions and exactly where to set a course for, you’ll be struck by the strength of the eddy currents rounding Cordova Spit. Don’t worry. According to the Sailing Directions, tidal streams are weak.

The spit’s intrusion into the channel creates a Venturi effect that actually makes the eddies stronger than the current. Decide whether to follow the main route around the east side of Saltspring Island or take the alternate up along the Vancouver coast. If following the primary route, head for the light at the northwest tip of James Island or go around the south end of the island, depending on current direction. Directions for the alternate route will follow immediately upon reaching both routes’ point of convergence.

A curved line is the loveliest distance between two points.

—MAE WEST

Bear with me with what might seem a somewhat confusing series of island descriptions and minor route variations. There is just a lot to do and visit here within very short distances, with none of it along a straight line.

James Island: James Island is the only island in the Gulf Islands that is completely surrounded by sand, in spite of its south end looking as if it has been hacked off by a giant meat cleaver. Feel free to land and linger, as long as you stay below the high tide line. From 1913 until the mid-1970s, James was home to an explosives and ammunition manufacturing plant and storage depot. In the 1980s the island was decommissioned and cleaned up. Currently owned by a Seattle billionaire, it is now a resort with plans for a portion to be set aside as a public marine park.

From James Island it is difficult to discern a clear target on Sidney Island for which to aim. From a kayaker’s perspective the low-lying spit, lagoon, and shoals at the north end, which encompass Sidney Spit Marine Park (mile 5/155), are a thin, monolithic, wavy mirage. One strategy is to head straight across Sidney Channel. Ebb tides in Sidney Channel can reach 3 knots; floods are not as strong. Once across, head north toward the light at the end of the spit. From this much closer perspective you’ll be able to make out the park’s public dinghy dock and approach channel as you coast north. This should be a snap if the tide is flooding. If it’s ebbing, what the hell, go south around Sidney, where you’ll be within nipping distance of D’Arcy Island, just across Hughes Passage. From the south end of Sidney, it’s best to follow the east coast up Miners Channel to the park (see Sidney Island on page 134).

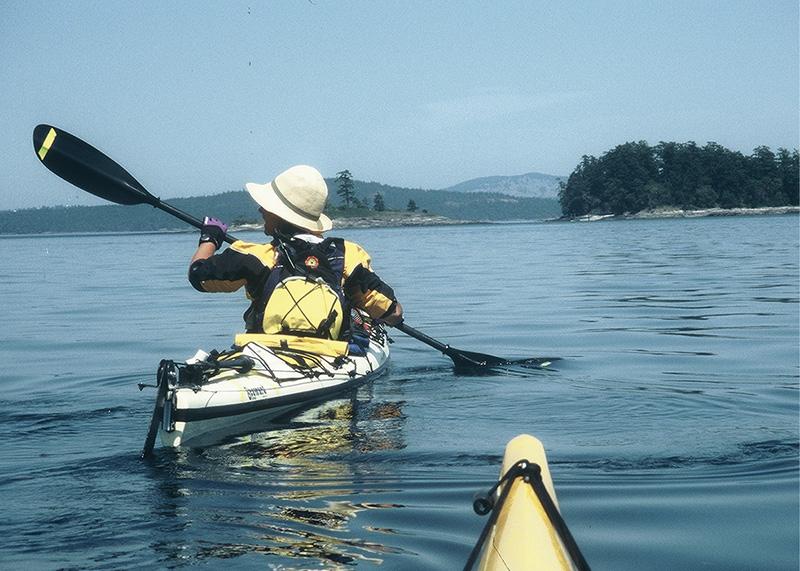

wendy paddling in the gulf islands

D’Arcy Island: D’Arcy Island, if you choose to visit, was a small Chinese leper colony until 1924 and a storehouse for bootleg whiskey. Leprosy was widespread in the Orient at the turn of the nineteenth century, and so occasionally Chinese immigrants coming to work on the railroads were found to be infected. Strict quarantine policies required isolation. Archaeological excavations in 1989 revealed six units of row housing. Since essential supplies arrived only every three months, inmates kept chickens and gardens. Not much was done to relieve the patients’ intense pain. Now it is an undeveloped marine park seldom visited by pleasure boaters, as there is no convenient anchorage. Head for the small bay just north of the light on the west shore. There are numerous fine beaches for camping. Deer and otters abound, and a colony of seals inhabits the rocks in the passage between D’Arcy and Little D’Arcy (private) Islands. Camping fees are on the honor system. There is no water, though there is a pit toilet.

Sidney Island: Sidney Spit Marine Park (mile 5/155) is at the north end of the island; the rest is private. The park, this section’s first possible campsite (not counting D’Arcy, which is just a tad off-route), is very popular and often crowded in parts, though there is plenty of room, especially if you camp away from the picnic tables. A small passenger ferry out of Sidney calls hourly. Toilets and water are available. Camp fees are collected by the camp host. A system of trails leads to a meadow and the remains of a brick mill that closed during WWI. One alternative, recommended by John Ince and Heidi Kottner in their 1982 guide (especially if you came up Miners Channel) is to head for the east side of the spit, just south of the piles, where no boats anchor and somewhat isolated camping can be found.

Mandarte Island: Going up Sidney’s east coast is a treat. Miners Channel was part of the main canoe route for prospectors heading to the Cariboo gold fields during the rush of the 1860s. Mandarte Island, about 1 mile to the east, is a gem. Over 15,000 nesting birds cover this massive, bare rock, filling the air with their cacophonous calls and pungent stink. Glaucus-winged gulls, pigeon guillemots, and pelagic and double-breasted cormorants abound. But the real treasure is the tufted puffins. Mandarte is the only place along the Inside Passage south of Glacier Bay where they nest. Their subterranean burrows are sometimes difficult to spot.

North of Sidney Spit, head for the unnamed archipelago that includes Little Group, Dock, Reay, Forrest, Domville, Brethour, Gooch, and Rum islands. Although the ultimate objective is Moresby Passage between Moresby and Portland islands, I will linger—as perhaps you might choose to also—on this archipelago, for it demands attention.

Going north, Forrest Island will probably be your first target. Limit stops to below the high-tide line as it is privately owned. Watch out for the twice-daily Sidney-Anacortes ferry.

Dock Island: Dock Island (mile 7/157), the easternmost member of the Little Group and slightly northwest of Forrest, has been reserved as a public recreation site with unimproved camping. Land on the pebble beach at the northwest end. The grassy tent sites have magnificent views but no shade. Hike through scrubby Garry oak to the steeply banked inlet on the south shore. Graffiti, visible on a nearby rock face, commemorates when, in 1972, the Nonsuch, a replica of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s sixteenth-century vessel, used this location to re-create “careening,” a method used to haul a sailing ship out before docks were constructed.

Domville and Brethour islands, just north and slightly east of Forrest, are private. Farther east are nearly contiguous Gooch and Rum islands. Although Gooch is also private, Rum is a provincial marine park. A tad out of the way, it is truly a Gulf Islands gem.

Rum Island: Less than a mile from the US border, Rum Island was a contraband stepping-stone during Prohibition. Now it has been re-designated Isle-de-Lis Provincial Marine Park. Its main attractions are the spectacular views of Haro Strait, Boundary Pass, and the San Juan Islands and remarkable wildflower displays, including the chocolate lily. The only place to land is the steep gravel isthmus connecting it to Gooch. Tenting is restricted (to preserve the wildflowers) to a half-dozen wooden platforms close by. Amenities consist of picnic tables, sanitary facilities, and a self-registration vault. There is no water.

Reay Island: Reay Island (mile 7/157—the same on-route distance as Dock Island) is dead on-route. The island, a public recreation site, is tiny, with two small sheltered landing coves. Just a few tents fit: no water, picnic tables, privies, or fees, though there is shade. No fires are allowed. The commanding views of Boundary Pass and Mount Baker and the hubbub of the animal kingdom espied from this lordly spot exalt.

From Reay Island, head north into Moresby Passage. Currents here can reach 3 knots during both ebb and flood, so plan accordingly. Moresby Island, on the east side, is private. On the other side, however, Portland Island is a marine park.

Portland Island: Princess Margaret Marine Park (mile 11/161) encompasses the whole of Portland Island. Three designated camping areas with picnic tables and toilets are located at Princess Bay (Tortoise Bay), Royal Cove, and Shell Beach, though camping is not limited to these sites. Camping fees are on the honor system, and a water pump is located near the center of the island (best accessed from Tortoise Bay). Trails connect all the improvements, and orientation maps are posted at Royal Cove and Tortoise Bay.

Princess Bay, on the southeast corner of the island, additionally protected by Hood Island and the Tortoise Islets (private), has an old apple orchard, meadow, and blackberry bushes. This is the most popular small craft anchorage on the island, and the Sidney-Sidney Spit passenger ferry occasionally calls here. Royal Cove, on the north end, has a couple of camp areas. One is located in the subsidiary cove just south of Royal, while the other, best accessed from its own gravel beach, is on Arbutus Point, which is the northeasternmost point on Portland. Nearby Chad Island is private. On the southwest corner of Portland lies the third camp area, Shell Beach. Just offshore lies Brackman Island, an ecological reserve created by the Nature Conservancy of Canada. Old-growth Douglas fir, sea blush, camas, white fawn and chocolate lilies, otters, mink, and harbor seals reside; Homo sapiens are not welcome.

One improvement not included in the trail system is the sunken wreck M/V G.B. Church, just off the Pellow Islets on the east coast. In 1991 the freighter was intentionally scuttled to create an artificial reef. Holes were cut in the hull to allow diver access. Anemones, sponges, and various other marine organisms have moved in and redecorated.

Coast Salish natives originally inhabited Portland Island. In the mid-1800s the island was deeded to Hawaiian natives, known as kanakas, by the Hudson’s Bay Company. They chose to settle there after their work contracts with the HBC expired. In the 1930s Major General Frank “One-Arm” Sutton acquired Portland; he settled and raised apples and thoroughbred horses. British Columbia got Portland in 1958 but then turned around and gave it to Princess Margaret Windsor in commemoration of her visit during the province’s centennial. Three years later she returned it so it could become a park, which it was so designated in 1967.

Going north from Portland, cross the intersection of Satellite and Swanson channels headed for Eleanor Point on Saltspring Island. Watch out for the Sidney-Tsawwassen ferry that runs twice hourly. Currents reach 1 to 2 knots.

Saltspring Island: Saltspring Island is the largest and most populous of the Gulf Islands. Its resident population of 11,000—mostly concentrated in the three villages of Ganges, Vesuvius, and Fulford—about triples during the summer months. Originally known as Klaathem by the Cowichans, it was renamed by the HBC for its brine pools, all of which lie inland. Saltspring was settled in the 1859 by free American blacks seeking to escape prejudice in the United States. Fat chance. An 1860 account reports: “The Indians always steadfastly refused to regard black men as entitled to any of the respect claimed by and shown to the whites. They also entertain the same feeling with regard to the Chinese.”

From Eleanor Point follow the coast up to Beaver Point, where Ruckle Provincial Park (mile 15/165) provides yet another camping opportunity. Ruckle is unique in that it combines a fully operational farm (with most of the original buildings, including the ornately Victorian Ruckle family house, circa 1872) with recreation. The campsites are south of Beaver Point, along the edge of the forest, across the open grassy area (accessible from shore), while the official docking area is just beyond the point in the small bay. Don’t worry about noisy car campers, as all the campsites are walk-in only. Water and toilets are available, as well as picnic tables at every site. Don’t miss the walk in the woods: some of the trees are over 6 feet in diameter.

Out of Ruckle Park, coast up the peninsula to Yeo Point and a good crossing of the Ganges Harbour mouth over to the Channel Islands. Ganges is the population center of Saltspring, and all services (except camping) are available. Then cross Captain Passage over to Prevost Island. Watch out for the interisland ferry that plies this passage.

Prevost Island: Prevost Island has been in the Digby Hussey de Burgh family since the 1920s. They still farm here. But James Bay and much of Selby Cove (mile 20/170) are now a BC Parks protected area. Undeveloped camping is allowed in a large meadow by the orchard next to the beach. Nearby Red Islets (south of Prevost) and Hawkins Islet (off the northeast coast) also have campsites.

From Selby Point, recross Captain Passage to Nose Point on Saltspring Island and head up Trincomali Channel along the Saltspring coast. Tidal streams in Trincomali Channel south of Wallace Island can attain 1.5 knots. Across Trincomali, on Galiano Island (hidden behind Parker Island), Montague Harbour Marine Park (mile 23/173—and 3 miles off-route) has camping and fresh water. Pass Walker Hook and Fernwood Point, where the small store carries produce, dairy, a deli, and some staples. From Fernwood veer north to Wallace Island. Currents in Trincomali Channel north of Wallace Island, due to the constriction, can double to 3 knots.

wallace island sandstone cliffs

Wallace Island: Wallace Island is a provincial marine park (mile 30/180) with three designated camping areas. Conover Cove is the first one you’ll encounter and the focal point of the park. Water is available from a pump; there are picnic tables, toilets, and a shelter—part of the old Chivers homestead—and also some gnarled fruit trees. For more isolated camping with powerful views, keep going up the southwest coast to Chivers Point at the north end of Wallace, where there are nine campsites. Probably the least visited campsite is Cabin Point (two sites), about half a mile from Chivers down the east coast of Wallace. Conover and Chivers have toilets, and all three are fee areas. A trail runs the length of the island. The alternate route rejoins the main route north of Wallace Island near mile 31/181.

Alternate Route: Island View Beach Park (mile 0/150) to Secretary Islands (mile 31/181) via west coast of Saltspring Island

Alternate Route: Island View Beach Park (mile 0/150) to Secretary Islands (mile 31/181) via west coast of Saltspring Island

Instead of heading out into the islands from Island View Beach Park, follow Cordova Channel up the Saanich Peninsula to Sidney, the second-largest city on Vancouver Island if you don’t count it as part of Victoria. Watch out for the Anacortes ferry, which docks at the north end of Bazan Bay. Another 0.75 mile north is the ferry terminal at Sidney Spit and Portland Island. Cross Sidney Harbour, Roberts Bay, and Tsehum Harbour to Curteis Point. There will be lots of traffic. Inside Tsehum Harbour lies McDonald Provincial Park (mile 7/157), the alternate put-in. All facilities are available.

North of Curteis Point, head for Swartz Head through the congested little archipelago that guards Canoe Cove, a large marina complex. During spring tides, swift currents can course through here. Swartz Bay, besides harboring the BC Ferries terminal to Tsawwassen, is a very busy place. Course westward along Colburne Passage to get out of the congestion and cross Satellite Channel to Saltspring Island. Head for Cape Keppel below the impressive flanks of Mount Tuam. Tidal streams attain 1 to 2 knots through Satellite Channel.

As you cross Satellite Channel, spare a thought for unique Saanich Inlet astern. While the depth across its mouth does not exceed 13 fathoms (78 feet), its central basin plunges sharply to 40 fathoms (240 feet). The deeper the water, the heavier the salt content and the lower the oxygen content. Tidal exchanges, unable to displace the cold, heavy water at the bottom, have little impact on the lower 20 fathoms (120 feet)—a marine black hole. Consequently, the inlet is highly susceptible to damage from runoff and every other type of pollution.

Three miles north of Cape Keppel you’ll hit Musgrave Rock or Island (depending on your map or chart), behind which is the only official campsite along the west side of Saltspring Island. The Musgrave BCMT campsite (mile15/165) is in the forest above the rocky gravel beach facing Musgrave Rock. The remains of an abandoned road (not visible from the water), which doesn’t quite reach the sea, allows for the flat space and clearing that make the campsite. There’s an outhouse, and water (filter, boil, or treat it) is available from the creek a short paddle away at Musgrave Landing behind Musgrave Point.

Sansum Narrows begin north of Musgrave and Separation Points. South of Burgoyne Bay tidal streams can run to 3 knots; north of it, 1.5 knots. The fjordlike, precipitous walls of Sansum Narrows are a sneak preview of upcoming attractions. Paddle north past Burial Islet, an old Indian burial site, then Bold Bluff Point, and cross or coast past Burgoyne Bay (mile 20/170) to Maxwell Point. Much of Burgoyne Bay has just been added to Mount Maxwell Provincial Park, with camping soon to be allowed. Notice the rare Garry oak groves along the north coast of Burgoyne. Notice too that visitation is prohibited in an effort to preserve this unique environment. At Erskine Point, Sansum Narrows are left behind and Stuart Channel begins. Cross Booth Bay to tiny Vesuvius, where you can quaff a pint at the waterside pub overlooking the bay. Water is available at a public tap on the second flower box on the main street. A small but quick and frequent ferry connects Vesuvius with Crofton on Vancouver Island.

North of Vesuvius head for Parminter Point, turn the corner, and set course for Idol Island. Idol, once an Indian burial ground, has only recently been designated a park preserve. Notice the shell midden on its west point. Though it looks to have a good campsite, landing is discouraged, as it remains a culturally significant First Nations site. Tent Island (mile 28/178), across Houstoun Passage and just south of Kuper Island, is an Indian reserve and requires prior permission from the Penelakut band for camping. Southey Point marks the northern extremity of Saltspring Island. Cross Houstoun Passage over to Jackscrew Island and the Secretaries to rejoin the normal route at mile 31/179.

Main Route: Continued . . .

Main Route: Continued . . .

Slip through the opening separating Wallace Island from South Secretary Island. These secretaries are charmingly inviting. Both, however, are private. A sandy tombolo connects the two at all but the highest tides—a camping opportunity for the confident tide table interpreter. Continue northwest to Mowgli Island and decide whether to favor eastward to Hall, Reid, and Valdes islands, or hop along the reefs and islets north of Thetis. At this point Trincomali Channel widens progressively north and currents are commensurately weaker until one reaches the constrictions at the north end of the Gulf Islands chain. All possible routes have diverse attractions. I’ll lay these out south to north; you can stitch your course.

Both Norway and Hall islands are private. The drying passage (only at zero tides) between Kuper and Thetis islands has a small marina with an ice cream parlor. Farther west is a shoreside pub.

Reid Island: Tiny Eden Islet off the southern tip of Reid Island is a recreation preserve (mile 34/184). Land on the rocky south end, where exposed flat ledges provide somewhat awkward kayak access. Flat, grassy mini-meadows on the south and northwest extremities make ideal campsites. There are no improvements. Do you go up the east or the west coast of Reid? That is the question. Though Reid is privately owned, about half a mile up its east side lies a small bay where camping is allowed. Alternatively, at the south end of the larger bay on the west coast, behind thick blackberry brambles, are the remains of a Japanese herring saltery built in 1908. During World War II all Japanese and Japanese Canadians were relocated and their properties confiscated. After the war, compensation was not provided.

Going up the west coast of Reid also puts you in a perfect position to navigate through the Rose Islets, an ecological reserve with a seal haul-out spot, just making a comeback after too much human disturbance. The Rose and Miami Islets are rookeries for the pelagic cormorant, a species that has experienced an unexplained decline in recent years. Paddle lightly and at a distance. The Ragged Islets (mile 37/187) have a campsite.

North of these disparate islets and reefs, all of the Gulf Island waters are channeled into two major arteries, Pylades and Stuart channels. These in turn squeeze tides through three very narrow openings at the north end of the island chain. I route you through False Narrows at the head of Pylades Channel, as it has the least traffic, the least current, and the shortest distance north. Both sides of Pylades Channel are dotted with interesting attractions, not all of which can be sampled by paddling in a straight line. First the west side of the channel, along the De Courcy Island group.

Pylades Island, all private, marks the south end of the group. Coastal Waters Recreation Maps indicate a campsite on the east shore of Pylades. Ruxton Island, also private, is next. Adjacent to its southeast shore lies 7-acre Whaleboat Island Marine Park (mile 41/191). Though one can camp here, the park is undeveloped, difficult to access, and short on space (best bet is on the northernmost point).

De Courcy Island: De Courcy Island, just north of Ruxton Passage, is mostly private except for its southeast appendage, Pirates Cove Marine Park (mile 43/193). There are two main access bays for the park: Pirates Cove on the north and Ruxton Passage Cove on the south. Pirates Cove is the more popular anchorage, as it offers greater protection; consequently, it can become crowded. At low tides it becomes a bug-infested and olfactory-assaulting bog trap. Kayakers should head for Ruxton Passage Cove, the closest access to the campground. A water pump, toilets, and fee collection site are all present.

Pirates Cove was once known as Gospel Cove, headquarters of the Aquarian Foundation, a millennial sect that made the island its home in the late 1920s. Edward Arthur Wilson, known to his followers as Brother XII, ran a tight ship. Converts were expected to pool their resources and contribute to the task of creating a self-sufficient colony. Some of the old buildings and an orchard along the western shore of De Courcy are all that remain from that era. From female converts the good brother expected sexual compliance, after which the whip-wielding Madame Zee, Wilson’s right-hand woman, would ensure the acolyte did her fair share of work. Cult conflicts soon involved the police and, inevitably, the courts. Tales of sordid sex, insanity, and misappropriation of funds became public. Wilson was tried but never convicted. He and Zee fled to Switzerland. No trace of the cult’s half ton of gold (said to be buried in 43 boxes) has ever been found.

Now for the east side of Pylades Channel.

Valdes Island: Valdes Island is almost completely uninhabited. About one-third of it is Native Reserve; the rest is private, with the exception of Blackberry Point (mile 39/189), an isolated piece of Crown land and a spacious, mostly undeveloped campground. The site has privy toilets and is maintained by the BCWTA, which charges a $5 per person fee. An extensive sandy beach surrounds the point; campsites—lots of possibilities—are either in the meadow or the madrona enclaves. To climb Mexicana Hill, the highest point on Valdes, paddle to an obvious little cove 0.5 mile north of Blackberry Point. Head up the old logging road and veer off on one of the many trails that lead in the general direction of the top. These are some serious views and it’s well worth the effort

According to Mary Ann Snowden in her excellent guide, Island Paddling:

Up until the beginning of this century, a large native population inhabited the southern shores of Valdes, living in one of three permanent villages. The largest village, Laysken, spread north and south of Shingle Point and had as many as ten houses and a population of two hundred. A smaller village at Cardale Point had five more houses and a total population of one hundred. The smallest site included three or four houses stretching from Cayetano Point to Vernaci Point (Rozen). The villages were abandoned when populations became so depleted that the remaining few inhabitants had to join up with related bands.

The Valdes Island side of Pylades is a pleasant paddle that becomes spectacular at the north end of the island. Wave erosion has carved magnificent, intricately carved sandstone galleries that stimulate the imagination. Sometimes, though, you can’t get very close. The area adjacent to and just south of Dibuxante Point is often used as a log booming berth by tugs awaiting suitable conditions to navigate Gabriola Passage. Still, it is quite an experience to paddle right next to millions of dollars worth of lumber on the float.

From Dibuxante Point, cross over to Gabriola Island at a respectful distance from the entrance to Gabriola Passage. Although the worst part of Gabriola Passage is between Cordero and Josef Points, expect turbulence, eddy lines, and funny water at the west entrance. Currents can run 8 knots, and their direction is seemingly counterintuitive. Ebbs flow west; floods flow east. Scope out your crossing well and, if in doubt, cross close to slack. Head for the protection of Degnen Bay, usually crowded and lacking any real facilities other than a government wharf. Degnen is the access point for a variety of prehistoric native petroglyph sites that are extensive, well preserved, easy to find, and now protected.

Degnen Bay, Gabriola Island: The first petroglyph, known as the “killer whale,” is 16 feet below the high-tide line, between the last two piers on the northeast shore, at the head of the bay on a sloping sandstone ledge. At low tide, land on the gravel beach between the aforementioned piers. Two other petroglyph sites, one with more than 50 glyphs, known as the Weldwood Site, require about a two-hour round-trip hike. It is well worth the effort. Park the boats well high on the beach near the government wharf. Follow the gravel road west from the wharf to its intersection with South Road. Turn left. Follow South Road for about a mile until you get to the Gabriola United Church at the intersection with Price Road. From the church parking lot a signed path leads to the Weldwood Site. In about 0.25 mile you’ll come to a distinctive clearing with two stone boulders marking the entrance. The carvings are incised on a horizontal sandstone slab and were discovered only in 1976, under a thin layer of grass and moss. Weldwood of Canada, the property owner, donated the site to the Crown. The depiction of a T-shaped labret on one of the carvings indicates a date (at least for that carving) of between 500 BC to AD 500.

petroglyphs near nanaimo

A third petroglyph group lies about 0.5 mile to the west. To reach these, retrace your steps back to the church. Go west on South Road for 0.5 mile to the Wheelbarrow Nursery. Take the old logging trail north for about 800 yards to a trail intersection near a large tree. Then take the path to the east and in 400 yards arrive at the third site.

The passage between De Courcy and Link islands is the last opportunity to slip over to Stuart Passage and Dodd Narrows; it dries only at low tide. Link and Mudge islands are connected by a tombolo that is covered only at the highest tides.

Time to slip through False Narrows. Dodd Narrows, boiling with whirlpools and rips, floods at 9 knots and ebbs at 8; much of the Nanaimo-Gulf Islands intermediate-size traffic favors it. Boats, from runabouts to tugs with log booms, congest the approaches prior to slack and the channel during the run. False Narrows, about a mile long, only runs at 4.5 knots and only during spring tides at that. Mostly small, local craft use it, as the channel is narrow, shallow, and choked with kelp. Although you need not wait for slack, you must at least go with the flow, though passage is not impossible at nearly any time.

Northumberland Channel, separating Gabriola from Vancouver Island just south of Nanaimo, is a de facto extension of Nanaimo Harbour and can be quite congested. The south shore is home to one of MacMillan Bloedel’s pulp mills; the Gabriola Island shore is the storage yard for the log booms. Two ferries crisscross. The Nanaimo-Tsaawwassen ferry departs from a new terminal at Jack Point; the Nanaimo-Gabriola Island ferry crosses from the inner harbor to Descanso Bay on Gabriola. A good strategy is to hug the shore between Duke and Jack Points and slip through after the departing Jack Point ferry (or under the pilings). The fish petroglyphs that once graced the fingertip of Jack’s Point have been removed and placed on display at the entrance to the museum in Nanaimo. Then work the foul south shore flats of Nanaimo Harbour until you can nip over to Protection Island behind, or well in front of, the Nanaimo-Gabriola Island ferry.